Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (/ˈlɪktənstaɪn/ (![]()

Principality of Liechtenstein | |

|---|---|

Motto: "Für Gott, Fürst und Vaterland" "For God, Prince, and Fatherland" | |

Anthem: (English: "High on the Young Rhine") | |

| |

_-_LIE_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) | |

| Capital | Vaduz |

| Largest municipality | Schaan 47°10′00″N 9°30′35″E |

| Official languages | German |

| Religion (2015[1]) | 83.2% Christianity —73.4% Roman Catholic (official) —9.8% Other Christian 7.0% No religion 5.9% Islam 3.9% Others |

| Demonym(s) | Liechtensteiner |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Hans-Adam II |

• Regent | Alois |

| Adrian Hasler | |

| Legislature | Landtag |

| Independence as principality | |

• Union between Vaduz and Schellenberg | 23 January 1719 |

| 12 July 1806 | |

• Separation from German Confederation | 24 August 1866 |

| Area | |

• Total | 160 km2 (62 sq mi) (191st) |

• Water (%) | 2.7[2] |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 38,749[3] (217th) |

• Density | 237/km2 (613.8/sq mi) (57th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $5.3 billion[4] (149th) |

• Per capita | $98,432[3][5][6] (1st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $5.155 billion[5][6] (147th) |

• Per capita | $143,151[3][5][6] (2nd) |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 18th |

| Currency | Swiss franc (CHF) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| UTC+02:00 (CEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +423 |

| ISO 3166 code | LI |

| Internet TLD | .li |

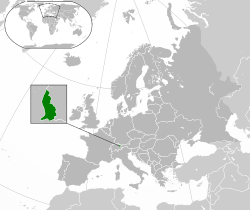

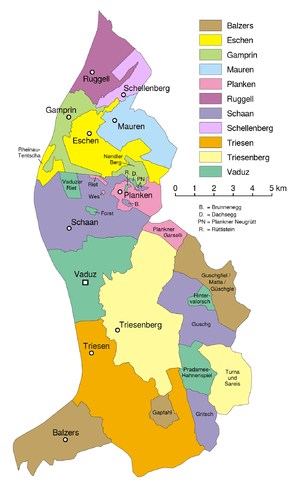

Liechtenstein is bordered by Switzerland to the west and south and Austria to the east and north. It is Europe's fourth-smallest country, with an area of just over 160 square kilometres (62 square miles) and a population of 38,749.[10] Divided into 11 municipalities, its capital is Vaduz, and its largest municipality is Schaan. It is also the smallest country to border two countries.[11] Liechtenstein is one of only two doubly landlocked countries in the world, along with Uzbekistan.

Economically, Liechtenstein has one of the highest gross domestic products per person in the world when adjusted for purchasing power parity.[12] The country has a strong financial sector centered in Vaduz. It was once known as a billionaire tax haven, but is no longer on any blacklists of uncooperative tax haven countries. An Alpine country, Liechtenstein is mountainous, making it a winter sport destination.

Liechtenstein is a member of the United Nations, the European Free Trade Association, and the Council of Europe. Although not a member of the European Union, it participates in both the Schengen Area and the European Economic Area. It also has a customs union and a monetary union with Switzerland.

History

Early history

The oldest traces of human existence in what is now Liechtenstein date back to the Middle Paleolithic era.[13] Neolithic farming settlements were initially founded in the valleys around 5300 BC.

The Hallstatt and La Tène cultures flourished during the late Iron Age, from around 450 BC—possibly under some influence of both the Greek and Etruscan civilisations. One of the most important tribal groups in the Alpine region were the Helvetii. In 58 BC, at the Battle of Bibracte, Julius Caesar defeated the Alpine tribes, therefore bringing the region under close control of the Roman Republic. By 15 BC, Tiberius—later the second Roman emperor—with his brother, Drusus, conquered the entirety of the Alpine area. Liechtenstein was then integrated into the Roman province of Raetia. The area was maintained by the Roman military, who also maintained large legionary camps at Brigantium (Austria), near Lake Constance, and at Magia (Swiss). A Roman road which ran through the territory was also created and maintained by these groups. In c.260, Brigantium was destroyed by the Alemanni, a Germanic people who settled in the area in around 450 AD.

In the Early Middle Ages, the Alemanni settled the eastern Swiss plateau by the 5th century and the valleys of the Alps by the end of the 8th century, with Liechtenstein located at the eastern edge of Alemannia. In the 6th century, the entire region became part of the Frankish Empire following Clovis I's victory over the Alemanni at Tolbiac in 504 AD.[14][15]

The area that later became Liechtenstein remained under Frankish hegemony (Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties), until the empire was divided by the Treaty of Verdun in 843 AD, following the death of Charlemagne.[13] The territory of present-day Liechtenstein was under the possession of East Francia. It would later be reunified with Middle Francia under the Holy Roman Empire, around 1000 AD.[13] Until about 1100, the predominant language of the area was Romansch, but thereafter German began to gain ground in the territory. In 1300, an Alemannic population—the Walsers, who originated in Valais—entered the region and settled. The mountain village of Triesenberg still preserves features of Walser dialect into the present century.[16]

Foundation of a dynasty

By 1200, dominions across the Alpine plateau were controlled by the Houses of Savoy, Zähringer, Habsburg, and Kyburg. Other regions were accorded the Imperial immediacy that granted the empire direct control over the mountain passes. When the Kyburg dynasty fell in 1264, the Habsburgs under King Rudolph I (Holy Roman Emperor in 1273) extended their territory to the eastern Alpine plateau that included the territory of Liechtenstein.[14] This region was enfeoffed to the Counts of Hohenems until the sale to the Liechtenstein dynasty in 1699.

In 1396 Vaduz (the southern region of Liechtenstein) gained imperial immediacy, i.e. it became subject to the Holy Roman Emperor alone.[17]

The family, from which the principality takes its name, originally came from Liechtenstein Castle in Lower Austria which they had possessed from at least 1140 until the 13th century (and again from 1807 onwards). The Liechtensteins acquired land, predominantly in Moravia, Lower Austria, Silesia, and Styria. As these territories were all held in feudal tenure from more senior feudal lords, particularly various branches of the Habsburgs, the Liechtenstein dynasty was unable to meet a primary requirement to qualify for a seat in the Imperial diet (parliament), the Reichstag. Even though several Liechtenstein princes served several Habsburg rulers as close advisers, without any territory held directly from the Imperial throne, they held little power in the Holy Roman Empire.

For this reason, the family sought to acquire lands that would be classed as unmittelbar (not sellable) or held without any intermediate feudal tenure, directly from the Holy Roman Emperor. During the early 17th century Karl I of Liechtenstein was made a Fürst (prince) by the Holy Roman Emperor Matthias after siding with him in a political battle. Hans-Adam I was allowed to purchase the minuscule Herrschaft ("Lordship") of Schellenberg and county of Vaduz (in 1699 and 1712 respectively) from the Hohenems. Tiny Schellenberg and Vaduz had exactly the political status required: no feudal lord other than their comital sovereign and the suzerain Emperor.

Principality

On 23 January 1719,[18] after the lands had been purchased, Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, decreed that Vaduz and Schellenberg were united and elevated the newly formed territory to the dignity of Fürstentum (principality) with the name "Liechtenstein" in honour of "[his] true servant, Anton Florian of Liechtenstein". It was on this date that Liechtenstein became a sovereign member state of the Holy Roman Empire. It is a testament to the pure political expediency of the purchase that the Princes of Liechtenstein did not visit their new principality for almost 100 years.

By the early 19th century, as a result of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, the Holy Roman Empire came under the effective control of France, following the crushing defeat at Austerlitz by Napoleon in 1805. Emperor Francis II abdicated, ending more than 960 years of feudal government. Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine. This political restructuring had broad consequences for Liechtenstein: the historical imperial, legal, and political institutions had been dissolved. The state ceased to owe an obligation to any feudal lord beyond its borders.[18]

Modern publications generally attribute Liechtenstein's sovereignty to these events. Its prince ceased to owe an obligation to any suzerain. From 25 July 1806, when the Confederation of the Rhine was founded, the Prince of Liechtenstein was a member, in fact, a vassal, of its hegemon, styled protector, the French Emperor Napoleon I, until the dissolution of the confederation on 19 October 1813.

Soon afterward, Liechtenstein joined the German Confederation (20 June 1815 – 24 August 1866), which was presided over by the Emperor of Austria.

In 1818, Prince Johann I granted the territory a limited constitution. In that same year Prince Aloys became the first member of the House of Liechtenstein to set foot in the principality that bore their name. The next visit would not occur until 1842.

Developments during the 19th century included:

- 1836, the first factory, for making ceramics, was opened.

- 1861, the Savings and Loans Bank was founded along with the first cotton-weaving mill.

- 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved.

- 1868, the Liechtenstein Army was disbanded for financial reasons.

- 1872, a railway line between Switzerland and the Austro-Hungarian Empire was constructed through Liechtenstein.

- 1886, two bridges over the Rhine to Switzerland were built.

20th century

Until the end of World War I, Liechtenstein was closely tied first to the Austrian Empire and later to Austria-Hungary; the ruling princes continued to derive much of their wealth from estates in the Habsburg territories, and spent much of their time at their two palaces in Vienna. The economic devastation caused by the war forced the country to conclude a customs and monetary union with its other neighbour, Switzerland.

At the time of the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was argued that Liechtenstein, as a fief of the Holy Roman Empire, was no longer bound to the emerging independent state of Austria, since the latter did not consider itself the legal successor to the empire. This is partly contradicted by the Liechtenstein perception that the dethroned Austro-Hungarian Emperor still maintained an abstract heritage of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1929, 75-year-old Prince Franz I succeeded to the throne. He had just married Elisabeth von Gutmann, a wealthy woman from Vienna whose father was a Jewish businessman from Moravia. Although Liechtenstein had no official Nazi party, a Nazi sympathy movement arose within its National Union party. Local Liechtenstein Nazis identified Elisabeth as their Jewish "problem".[19]

In March 1938, just after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Franz named as regent his 31-year-old grandnephew and heir-presumptive, Prince Franz Joseph. Franz died in July that year, and Franz Joseph succeeded to the throne. Franz Joseph II first moved to Liechtenstein in 1938, a few days after Austria's annexation.[17]

During World War II, Liechtenstein remained officially neutral, looking to neighbouring Switzerland for assistance and guidance, while family treasures from dynastic lands and possessions in Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia were taken to Liechtenstein for safekeeping. At the close of the conflict, Czechoslovakia and Poland, acting to seize what they considered German possessions, expropriated the entirety of the Liechtenstein dynasty's properties in those three regions. The expropriations (subject to modern legal dispute at the International Court of Justice) included over 1,600 km2 (618 sq mi) of agricultural and forest land (most notably the UNESCO listed Lednice–Valtice Cultural Landscape), and several family castles and palaces.

In 2005 it was revealed that Jewish labourers from the Strasshof concentration camp, provided by the SS, had worked on estates in Austria owned by Liechtenstein's Princely House.[20]

Citizens of Liechtenstein were forbidden to enter Czechoslovakia during the Cold War. More recently the diplomatic conflict revolving around the controversial postwar Beneš decrees resulted in Liechtenstein not sharing international relations with the Czech Republic or Slovakia. Diplomatic relations were established between Liechtenstein and the Czech Republic on 13 July 2009,[21][22][23] and with Slovakia on 9 December 2009.[24]

Financial centre

Liechtenstein was in dire financial straits following the end of the war in Europe. The Liechtenstein dynasty often resorted to selling family artistic treasures, including the portrait Ginevra de' Benci by Leonardo da Vinci, which was purchased by the National Gallery of Art of the United States in 1967 for US$5 million ($38 million in 2019 dollars), then a record price for a painting.

By the late 1970s, Liechtenstein used its low corporate tax rates to draw many companies, and became one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

As of September 2008 the Prince of Liechtenstein is the world's eighth wealthiest monarch, with an estimated wealth of US$3.5 billion.[25] The country's population enjoys one of the world's highest standards of living.

Government

_by_Erling_Mandelmann.jpg)

Liechtenstein has a monarch as Head of State, and an elected parliament that enacts the law. It is also a direct democracy, where voters can propose and enact constitutional amendments and legislation independently of the legislature. The Constitution of Liechtenstein was adopted in March 2003, replacing the 1921 constitution. The 1921 constitution had established Liechtenstein as a constitutional monarchy headed by the reigning prince of the Princely House of Liechtenstein; a parliamentary system had been established, although the reigning Prince retained substantial political authority.

The reigning Prince is the head of state and represents Liechtenstein in its international relations (although Switzerland has taken responsibility for much of Liechtenstein's diplomatic relations). The Prince may veto laws adopted by parliament. The Prince can call referenda, propose new legislation, and dissolve parliament, although dissolution of parliament may be subject to a referendum.[26]

Executive authority is vested in a collegiate government comprising the head of government (prime minister) and four government councilors (ministers). The head of government and the other ministers are appointed by the Prince upon the proposal and concurrence of parliament, reflecting the partisan balance of parliament. The constitution stipulates that at least two members of the government be chosen from each of the two regions.[27] The members of the government are collectively and individually responsible to parliament; parliament may ask the Prince to remove an individual minister or the entire government.

Legislative authority is vested in the unicameral Landtag, made up of 25 members elected for maximum four-year terms according to a proportional representation formula. Fifteen members are elected from the Oberland (Upper Country or region) and ten from the Unterland (Lower Country or region).[28] Parties must receive at least 8% of the national vote to win seats in parliament, i.e. enough for 2 seats in the 25-seat legislature. Parliament proposes and approves a government, which is formally appointed by the Prince. Parliament may also pass votes of no confidence in the entire government or individual members.

Parliament elects from among its members a "Landesausschuss" (National Committee) made up of the president of the parliament and four additional members. The National Committee is charged with performing parliamentary oversight functions. Parliament can call for referenda on proposed legislation. Parliament shares the authority to propose new legislation with the Prince and with the number of citizens required for an initiative referendum.[29]

Judicial authority is vested in the Regional Court at Vaduz, the Princely High Court of Appeal at Vaduz, the Princely Supreme Court, the Administrative Court, and the State Court. The State Court rules on the conformity of laws with the constitution and has five members elected by parliament.

On 1 July 1984, Liechtenstein became the last country in Europe to grant women the right to vote. The referendum on women's suffrage, in which only men were allowed to participate, passed with 51.3% in favour.[30]

New constitution

In a national referendum in March 2003, nearly two-thirds of the electorate voted in support of Hans-Adam II's proposed new constitution. The proposed constitution was criticised by many, including the Council of Europe, as expanding the powers of the monarchy (continuing the power to veto any law, and allowing the Prince to dismiss the government or any minister). The Prince threatened that if the constitution failed, he would, among other things, convert some royal property for commercial use and move to Austria.[31] The princely family and the Prince enjoy tremendous public support inside the nation, and the resolution passed with about 64% in favour.[32] A proposal to revoke the Prince's veto powers was rejected by 76% of voters in a 2012 referendum.[33]

Municipalities in Liechtenstein are entitled to secede from the union by majority vote.[34]

International awards

In 2013, Liechtenstein won for the first time a SolarSuperState Prize in the category Solar recognizing the achieved level of the usage of photovoltaics per population within the state territory.[35] The SolarSuperState Association justified this prize with the cumulative installed photovoltaic power of some 290 Watt per capita at the end of 2012. This placed Liechtenstein second in the world after Germany. Also in 2014, the SolarSuperState Association awarded the second place SolarSuperState Prize in the category Solar to Liechtenstein.[36] In the years 2015 and 2016, Liechtenstein was honored with the first place SolarSuperState Prize in the category Solar because it had the world's biggest cumulative installed photovoltaic power per population.[37][38]

Geography

Liechtenstein is situated in the Upper Rhine valley of the European Alps and is bordered to the east by the Austrian region of Vorarlberg and to the south by the canton of Grisons (Switzerland) and to the west by the canton of St. Gallen (Switzerland). The entire western border of Liechtenstein is formed by the Rhine. Measured south to north the country is about 24 km (15 mi) long. Its highest point, the Grauspitz, is 2,599 m (8,527 ft). Despite its Alpine location, prevailing southerly winds make the climate comparatively mild. In winter, the mountain slopes are well suited to winter sports.

New surveys using more accurate measurements of the country's borders in 2006 have set its area at 160 km2 (62 sq mi), with borders of 77.9 km (48.4 mi).[39] Liechtenstein's borders are 1.9 km (1.2 mi) longer than previously thought.[40]

Liechtenstein is one of the world's two doubly landlocked countries[41] — countries wholly surrounded by other landlocked countries (the other is Uzbekistan). Liechtenstein is the sixth-smallest independent nation in the world by area.

The principality of Liechtenstein is divided into 11 communes called Gemeinden (singular Gemeinde). The Gemeinden mostly consist of only a single town or village. Five of them (Eschen, Gamprin, Mauren, Ruggell, and Schellenberg) fall within the electoral district Unterland (the lower county), and the remainder (Balzers, Planken, Schaan, Triesen, Triesenberg, and Vaduz) within Oberland (the upper county).

Economy

Despite its limited natural resources, Liechtenstein is one of the few countries in the world with more registered companies than citizens; it has developed a prosperous, highly industrialized free-enterprise economy and boasts a financial service sector as well as a living standard that compares favourably with those of the urban areas of Liechtenstein's much larger European neighbours.

Liechtenstein participates in a customs union with Switzerland and employs the Swiss franc as the national currency. The country imports about 85% of its energy. Liechtenstein has been a member of the European Economic Area (an organization serving as a bridge between the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and the European Union) since May 1995.

The government is working to harmonize its economic policies with those of an integrated Europe. In 2008, the unemployment rate stood at 1.5%. Liechtenstein has only one hospital, the Liechtensteinisches Landesspital in Vaduz. As of 2014 the CIA World Factbook estimated the gross domestic product (GDP) on a purchasing power parity basis to be $4.978 billion. As of 2009 the estimate per capita was $139,100, the highest listed for the world.[41]

Industries include electronics, textiles, precision instruments, metal manufacturing, power tools, anchor bolts, calculators, pharmaceuticals, and food products. Its most recognizable international company and largest employer is Hilti, a manufacturer of direct fastening systems and other high-end power tools. Many cultivated fields and small farms are found both in the Oberland and Unterland. Liechtenstein produces wheat, barley, corn, potatoes, dairy products, livestock, and wine. Tourism accounts for a large portion of its economy.

Taxation

The government of Liechtenstein taxes personal income, business income, and principal (wealth). The basic rate of personal income tax is 1.2%. When combined with the additional income tax imposed by the communes, the combined income tax rate is 17.82%.[42] An additional income tax of 4.3% is levied on all employees under the country's social security programme. This rate is higher for the self-employed, up to a maximum of 11%, making the maximum income tax rate about 29% in total. The basic tax rate on wealth is 0.06% per annum, and the combined total rate is 0.89%. The tax rate on corporate profits is 12.5%.[41]

Liechtenstein's gift and estate taxes vary depending on the relationship the recipient has to the giver and the amount of the inheritance. The tax ranges between 0.5% and 0.75% for spouses and children and 18% to 27% for non-related recipients. The estate tax is progressive.

Liechtenstein has previously received significant revenues from Stiftungen ("foundations"), financial entities created to hide the true owner of nonresident foreigners' financial holdings. The foundation is registered in the name of a Liechtensteiner, often a lawyer. This set of laws used to make Liechtenstein a popular tax haven for extremely wealthy individuals and businesses attempting to avoid or evade taxes in their home countries.[43] In recent years, Liechtenstein has displayed stronger determination to prosecute international money launderers and worked to promote an image as a legitimate finance center. In February 2008, the country's LGT Bank was implicated in a tax-fraud scandal in Germany, which strained the ruling family's relationship with the German government. Crown Prince Alois has accused the German government of trafficking in stolen goods, referring to its $7.3 million purchase of private banking information offered by a former employee of LGT Group.[44][45] The United States Senate's subcommittee on tax haven banks said that the LGT bank, owned by the princely family, and on whose board they serve, "is a willing partner, and an aider and abettor to clients trying to evade taxes, dodge creditors or defy court orders".[46]

The 2008 Liechtenstein tax affair is a series of tax investigations in numerous countries whose governments suspect that some of their citizens have evaded tax obligations by using banks and trusts in Liechtenstein; the affair broke open with the biggest complex of investigations ever initiated for tax evasion in Germany.[47] It was also seen as an attempt to put pressure on Liechtenstein, then one of the remaining uncooperative tax havens—along with Andorra and Monaco—as identified by the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2007.[48] On 27 May 2009 the OECD removed Liechtenstein from the blacklist of uncooperative countries.[49]

In August 2009, the British government department HM Revenue & Customs agreed with Liechtenstein to start exchanging information. It is believed that up to 5,000 British investors have roughly £3 billion deposited in accounts and trusts in the country.[50]

In October 2015, the European Union and Liechtenstein signed a tax agreement to ensure the automatic exchange of financial information in case of tax disputes. The collection of data started in 2016, and is another step to bring the principality in line with other European countries with regard to its taxation of private individuals and corporate assets.[51]

Demographics

Population-wise, Liechtenstein is Europe's fourth-smallest country; Vatican City, San Marino, and Monaco have fewer residents. Its population is primarily Alemannic-speaking, although one third is foreign-born, primarily German speakers from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, along with other Swiss, Italians, and Turks. Foreign-born people make up two-thirds of the country's workforce.[52]

Liechtensteiners have an average life expectancy at birth of 82.0 years, subdividing as male: 79.8 years, female: 84.8 years (2018 est.). The infant mortality rate is 4.2 deaths per 1,000 live births, according to 2018 estimates.

Languages

The official language is German; most speak an Alemannic dialect of German that is highly divergent from Standard German but closely related to dialects spoken in neighbouring regions such as Switzerland and Vorarlberg, Austria. In Triesenberg, a Walser German dialect promoted by the municipality is spoken. Swiss Standard German is also understood and spoken by most Liechtensteiners.

Religion

Religion in Liechtenstein in 2010[53]

According to the Constitution of Liechtenstein, Catholicism is its official state religion:

The Catholic Church is the State Church and as such shall enjoy the full protection of the State

Liechtenstein offers protection to adherents of all religions, and considers the "religious interests of the people" a priority of the government.[54] In Liechtenstein schools, although exceptions are allowed, religious education in Roman Catholicism or Protestantism (either Reformed or Lutheran, or both) is legally required.[55] Tax exemption is granted by the government to religious organizations.[55] According to the Pew Research Center, social conflict caused by religious hostilities is low in Liechtenstein, and so is government restriction on the practice of religion.[56]

According to the 2010 census, 85.8% of the total population is Christian, of whom 75.9% adhere to the Roman Catholic faith, constituted in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vaduz, while 9.6% are either Protestant, mainly organized in the Evangelical Church in Liechtenstein (a United church, Lutheran & Reformed) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Liechtenstein, or Orthodox, mainly organized in the Christian-Orthodox Church.[57] The largest minority religion is Islam (5.4% of the total population).[53]

| Religion[58] | 2010 | 2000 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catholics | 75.9% | 78.4% | 84.9% |

| Protestants | 8.5% | 8.3% | 9.2% |

| Christian-Orthodox Churches | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.7% |

| Other Christian Churches | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Muslims | 5.4% | 4.8% | 2.4% |

| Other religions | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.2% |

| No religion | 5.4% | 2.8% | 1.5% |

| Undeclared | 2.6% | 4.1% | 0.9% |

Education

The literacy rate of Liechtenstein is 100%.[41] In 2006 Programme for International Student Assessment report, coordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ranked Liechtenstein's education as the 10th best in the world.[59] In 2012, Liechtenstein had the highest PISA-scores of any European country.[60]

Within Liechtenstein, there are four main centres for higher education:

- University of Liechtenstein

- Private University in the Principality of Liechtenstein

- Liechtenstein Institute

- International Academy of Philosophy, Liechtenstein

There are nine public high schools in the country. These include:

- Liechtensteinisches Gymnasium in Vaduz.

- Realschule Vaduz and Oberschule Vaduz, in the Schulzentrum Mühleholz II in Vaduz[61]

- Realschule Schaan and Sportschule Liechtenstein in Schaan[61]

Transport

There are about 250 km (155 miles) of paved roadway within Liechtenstein, with 90 km (56 miles) of marked bicycle paths.

A 9.5 km (5.9 mi) railway connects Austria and Switzerland through Liechtenstein. The country's railways are administered by the Austrian Federal Railways as part of the route between Feldkirch, Austria, and Buchs, Switzerland. Liechtenstein is nominally within the Austrian Verkehrsverbund Vorarlberg[62] tariff region.

There are four railway stations in Liechtenstein, namely Schaan-Vaduz, Forst Hilti, Nendeln and Schaanwald, served by an irregularly stopping train service between Feldkirch and Buchs provided by Austrian Federal Railways. While EuroCity and other long-distance international trains also travel along the route, they do not normally call at the stations within the borders of Liechtenstein.

Liechtenstein Bus is a subsidiary of the Swiss Postbus system, but separately run, and connects to the Swiss bus network at Buchs and at Sargans. Buses also run to the Austrian town of Feldkirch.

Liechtenstein has no airport. The nearest large airport is Zurich Airport near Zürich, Switzerland (130 km or 80 miles by road). The nearest small airport is St. Gallen Airport (50 km or 30 miles). Friedrichshafen Airport also provides access to Liechtenstein, as it is 85 km (53 miles) away. Balzers Heliport is[63][64] available for chartered helicopter flights.

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Liechtenstein |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media

|

| Sport |

|

Symbols |

As a result of its small size, Liechtenstein has been strongly affected by external cultural influences, most notably those originating in the southern regions of German-speaking Europe, including Austria, Baden-Wurttemberg, Bavaria, Switzerland, and specifically Tirol and Vorarlberg. The "Historical Society of the Principality of Liechtenstein" plays a role in preserving the culture and history of the country.

The largest museum is the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, an international museum of modern and contemporary art with an important international art collection. The building by the Swiss architects Morger, Degelo, and Kerez is a landmark in Vaduz. It was completed in November 2000 and forms a "black box" of tinted concrete and black basalt stone. The museum collection is also the national art collection of Liechtenstein.

The other important museum is the Liechtenstein National Museum (Liechtensteinisches Landesmuseum) showing permanent exhibition on the cultural and natural history of Liechtenstein as well as special exhibitions. There is also a stamp museum, ski museum, and a 500-year-old Rural Lifestyle Museum.

The Liechtenstein State Library is the library that has legal deposit for all books published in the country.

The most famous historical sites are Vaduz Castle, Gutenberg Castle, the Red House and the ruins of Schellenberg.

The Private Art Collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein, one of the world's leading private art collections, is shown at the Liechtenstein Museum in Vienna.

On the country's national holiday all subjects are invited to the castle of the head of state. A significant portion of the population attends the national celebration at the castle where speeches are made and complimentary beer is served.[65]

Music and theatre are an important part of the culture. There are numerous music organizations such as the Liechtenstein Musical Company, the annual Guitar Days, and the International Josef Gabriel Rheinberger Society, which play in two main theatres.

Airbnb

Though it initially sounds like fiction, Airbnb offered an ability to rent Liechtenstein for about 70,000 USD. Although the deal, as of August 2020, is no longer available, the entire country could be rented out.[66] For a minimum of 2 nights you could rent the entire country which has a population of 75,000 (at the time) and is supposedly capable of holding 450–900 guests. The airbnb profile says," Liechtenstein can accommodate between 450 and 900 people, has 500+ bedrooms and 500+ bathrooms."[67]

Media

The primary internet service provider and mobile network operator of Liechtenstein is Telecom Liechtenstein, located in Schaan. There is only one television channel in the country, the private channel 1FLTV created in 2008. At the moment, 1FLTV is not a member of the European Broadcasting Union. L-Radio, which was established in 2004, serves as Liechtenstein's radio station and is based in Triesen. L-Radio has a listener base of 50,000 and began as "air Radio Liechtenstein" on 15 October 1938. Liechtenstein also has two major newspapers; Liechtensteiner Volksblatt and Liechtensteiner Vaterland. The primary multimedia company in Liechtenstein is ManaMedia, located in Vaduz.

Amateur radio is a hobby of some nationals and visitors. However, unlike virtually every other sovereign nation, Liechtenstein does not have its own ITU prefix. It uses Switzerland's callsign prefixes (typically "HB") followed by a zero.

Sports

Liechtenstein football teams play in the Swiss football leagues. The Liechtenstein Football Cup allows access for one Liechtenstein team each year to the UEFA Europa League; FC Vaduz, a team playing in the Swiss Challenge League, the second division in Swiss football, is the most successful team in the Cup, and scored their greatest success in the European Cup Winners' Cup in 1996 when they drew with and defeated the Latvian team FC Universitate Riga by 1–1 and 4–2, to go on to a lucrative fixture against Paris Saint-Germain F.C., which they lost 0–3 and 0–4.

The Liechtenstein national football team is regarded as an easy target for any team drawn against them; this was the basis for a book about Liechtenstein's unsuccessful qualifying campaign for the 2002 World Cup by British author Charlie Connelly. In one surprising week during autumn 2004, however, the team managed a 2–2 draw with Portugal, who only a few months earlier had been the losing finalists in the European Championships. Four days later, the Liechtenstein team traveled to Luxembourg, where they defeated the home team 4–0 in a 2006 World Cup qualifying match. In the qualification stage of the European Championship 2008, Liechtenstein beat Latvia 1–0, a result which prompted the resignation of the Latvian coach. They went on to beat Iceland 3–0 on 17 October 2007, which is considered one of the most dramatic losses of the Icelandic national football team. On 7 September 2010, they came within seconds of a 1–1 draw against Scotland in Glasgow, having led 1–0 earlier in the second half, but Liechtenstein lost 2–1 thanks to a goal by Stephen McManus in the 97th minute. On 3 June 2011, Liechtenstein defeated Lithuania 2–0. On 15 November 2014, Liechtenstein defeated Moldova 0–1 with Franz Burgmeier's late free kick goal in Chișinău.

As an alpine country, the main sporting opportunity for Liechtensteiners to excel is in winter sports such as downhill skiing: the country's single ski area is Malbun. Hanni Wenzel won two gold medals and one silver medal in the 1980 Winter Olympics (she won bronze in 1976), her brother Andreas won one silver medal in 1980 and one bronze medal in 1984 in the giant slalom event, and her daughter Tina Weirather won a bronze medal in 2018 in the Super-G. With ten medals overall (all in alpine skiing), Liechtenstein has won more Olympic medals per capita than any other nation.[68] It is the smallest nation to win a medal in any Olympics, Winter or Summer, and the only nation to win a medal in the Winter Games but not in the Summer Games. Other notable skiers from Liechtenstein are Marco Büchel, Willi Frommelt, Paul Frommelt and Ursula Konzett. Liechtenstein is also the home country of Stephanie Vogt, a professional women's tennis player.

Motorsport

In March 2020 swiss Comedian Michael v. Tell set a new world record with the E-Harley LiveWire. Within 24 hours he drove 1,723 kilometres (1,071 mi) under standard conditions, with a single driver. The Record was reported all over the world and was done in cooperation with Switzerland, Austria, Germany and Liechtenstein. Finish line was Ruggell in Liechtenstein so it was a highlight in the of Liechtenstein Motorsport history.[69][70][71]

Youth

Liechtenstein competes in the Switzerland U16 Cup Tournament, which offers young players an opportunity to play against top football clubs.

Security and defence

The Liechtenstein National Police is responsible for keeping order within the country. It consists of 87 field officers and 38 civilian staff, totaling 125 employees. All officers are equipped with small arms. The country has one of the world's lowest crime rates. Liechtenstein's prison holds few, if any, inmates, and those with sentences over two years are transferred to Austrian jurisdiction. The Liechtenstein National Police maintains a trilateral treaty with Austria and Switzerland that enables close cross-border cooperation among the police forces of the three countries.[72]

Liechtenstein follows a policy of neutrality and is one of the few countries in the world that maintain no military. The army was abolished soon after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, in which Liechtenstein fielded an army of 80 men, although they were not involved in any fighting. No casualties were incurred, in fact the unit numbered 81 upon return due to an Italian joining with the unit to escape the war zone.[73] The demise of the German Confederation in that war freed Liechtenstein from its international obligation to maintain an army, and parliament seized this opportunity and refused to provide funding for one. The Prince objected, as such a move would leave the country defenceless, but relented on 12 February 1868 and disbanded the force. The last soldier to serve under the colors of Liechtenstein died in 1939 at age 95.[74]

During the 1980s the Swiss Army fired off shells during an exercise and mistakenly burned a patch of forest inside Liechtenstein. The incident was said to have been resolved "over a case of white wine".[65]

In March 2007, a 170-man Swiss infantry unit got lost during a training exercise and inadvertently crossed 1.5 km (0.9 miles) into Liechtenstein. The accidental invasion ended when the unit realized their mistake and turned back.[75] The Swiss Army later informed Liechtenstein of the incursion and offered official apologies,[76] to which an internal ministry spokesperson responded, "No problem, these things happen."[77]

In 2017, Liechtenstein signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[78]

See also

References

- "Central Intelligence Agency". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Raum, Umwelt und Energie Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Landesverwaltung Liechtenstein. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Amt für Statistik, Landesverwaltung Liechtenstein". Llv.li. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Liechtenstein in Figures: 2016" (PDF). Llv.li. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Key Figures for Liechtenstein Archived 17 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine Landesverwaltung Liechtenstein. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- World Development Indicators, World Bank. Retrieved 1 July 2012. Note: "PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $)" and "Official exchange rate (LCU per US$, period average)" for Switzerland were used.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Duden Aussprachewörterbuch, s.v. "Liechtenstein[er]".

- "IGU regional conference on environment and quality of life in central Europe". GeoJournal. 28 (4). 1992. doi:10.1007/BF00273120.

- Bevölkerungsstatistik. Amt für Statistik. Liechtenstein. 30 June 2019

- "The smallest countries in the world by area". www.countries-ofthe-world.com. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- CIA – The World Factbook – Country Comparison :: GDP – per capita (PPP) Cia.gov. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- History. swissworld.org. Retrieved 27 June 2009

- Switzerland history Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 November 2009

- History of Switzerland Nationsonline.org. Retrieved 27 November 2009

- P. Christiaan Klieger, The Microstates of Europe: Designer Nations in a Post-Modern World (2014), p. 41

- Eccardt, Thomas (2005). Secrets of the Seven Smallest States of Europe. Hippocrene Books. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7818-1032-6.

- "History, creation of Liechtenstein". liechtenstein.li. Liechtenstein Marketing. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Liechtenstein: Nazi Pressure?". Time. New York. 11 April 1938. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- "Nazi crimes taint Liechtenstein". BBC News. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- "Liechtenstein and the Czech Republic establish diplomatic relations" (PDF). Government Spokesperson's Office, the Principality of Liechtenstein. 13 July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- "Navázání diplomatických styků České republiky s Knížectvím Lichtenštejnsko" [Establishment of diplomatic relations with the Czech Republic and the Principality of Liechtenstein] (in Czech). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic. 13 July 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- "MINA Breaking News – Decades later, Liechtenstein and Czechs establish diplomatic ties". Macedoniaonline.eu. 15 July 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- "Liechtenstein and the Slovak Republic establish diplomatic relations" (PDF). Government Spokesperson's Office, the Principality of Liechtenstein. 9 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- D. Pendleton; C. Vorasasun; C. von Zeppelin; T. Serafin (1 September 2008). "The Top 15 Wealthiest Royals". Forbes. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- "Country profile: Liechtenstein – Leaders". BBC News. 6 December 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "Principality of Liechtenstein – Government". Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2010.. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- "Principality of Liechtenstein website – Parliamentary elections". Archived from the original on 7 August 2004. Retrieved 11 January 2010.. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- "Principality of Liechtenstein website – Parliamentary Organization". Archived from the original on 11 October 2004. Retrieved 11 January 2010.. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- "Liechtenstein Women Win Right to Vote". The New York Times. 2 July 1984. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- "Liechtenstein Prince wins powers". BBC News. 16 March 2003. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "IFES Election Guide – Election Profile for Liechtenstein – Results". Electionguide.org. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "Liechtenstein votes to keep prince's veto". Reuters. 1 July 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "Constitution of Liechtenstein" (PDF). 1 February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2013.

Chapter I, Article 4

- "Auszeichnung für das Land Liechtenstein". Volksblatt. 23 August 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Fotovoltaik: Eigenverbrauch soll stärker forciert werden". Volksblatt. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Wir sind Solarstrom-Weltmeister 2015". Volksblatt. 29 June 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Liechtenstein erneut Solar-Weltmeister". Liechtensteiner Vaterland. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Tiny Liechtenstein gets a little bigger", 29 December 2006.

- "Liechtenstein redraws Europe map". BBC News. 28 December 2006.

- "Liechtenstein". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Encyclopedia of the Nations. Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- "Billionaire Tax Haven Liechtenstein Loses on Bank Reforms". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Wiesmann, Gerrit (23 February 2008). "Lilliput's giant-slayer." Financial Times. London.

- "Pro Libertate: A Parasite's Priorities (Updated, February 23)". Freedominourtime.blogspot.com. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- "Tax Me If You Can". ABC News Australia. 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- "Skandal gigantischen Ausmaßes". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Munich. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- Esterl, Mike; Simpson, Glenn R.; Crawford, David (19 February 2008). "Stolen Data Spur Tax Probes". The Wall Street Journal. New York. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- Removal from OECD List of Unco-operative Tax Havens. Oecd.org. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- "UK signs Liechtenstein tax deal". BBC News. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- "EU and Liechtenstein sign deal on automatic exchange of tax data" (Press release). Brussels: European Council. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "WT/TPR/S/280 • Switzerland and Liechtenstein" (PDF). WTO. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- "Volkszählung 2010". Llv.li. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Jeroen Temperman (30 May 2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law: Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance. BRILL. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-90-04-18148-9. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- Aili Piano (30 September 2009). Freedom in the World 2009: The Annual Survey of Political Rights & Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 426. ISBN 978-1-4422-0122-4. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Global Restrictions on Religion" (PDF). Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- "Aktuell :: Orthodoxie". www.orthodoxie.li (in German). Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Statistisches Jahrbuch Liechtensteins" (PDF). Llv.li. 2014. p. 80. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Range of rank on the PISA 2006 science scale. Retrieved 24 December 2011

- "PISA 2012 Results in Focus" (PDF). Paris: OECD. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- "Weiterführende Schulen Schaan." Commune of Schaan. Retrieved 12 May 2016. "Realschule Schaan Duxgass 55 9494 Schaan" and "Sportschule Liechtenstein Duxgass 55 9494 Schaan" and "Realschule Vaduz Schulzentrum Mühleholz II 9490 Vaduz" and "Oberschule Vaduz Schulzentrum Mühleholz II 9490 Vaduz"

- Verkehrsverbund Vorarlberg. Vmobil.at. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- Heliport Balzers FL LSXB. Tsis.ch. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- Heliports – Balzers LSXB – Heli-Website von Matthias Vogt. Heli.li. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- Letzing, John (16 April 2014). "Liechtenstein Gets Even Smaller". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- UK, Wired (15 April 2011). "Rent the country of Liechtenstein for $70,000 a night". Wired. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- www.themarysue.com https://www.themarysue.com/rent-liechtenstein-airbnb/. Retrieved 10 August 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Per Capita Olympic Medal Table". Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- "CNBC World record". CNBC World record.

- "Press Review Video". Press Review Video.

- "Blick Swiss record". Blick Swiss record.

- "Liechtenstein – facts and figures" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2006. Retrieved 2 May 2010.. Office for Foreign Affairs of Liechtenstein.

- "Liechtenstein" (PDF). Lonely Planet Publications. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Beattie, David (2004). Liechtenstein: A Modern History. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-85043-459-7.

- CBC News (2 March 2007). "Not-so-precise Swiss army unit mistakenly invades Liechtenstein". CBC News. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Hamilton, Lindsay (3 March 2007). "Whoops! Swiss Accidentally Invade Liechtenstein". ABC News. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Brook, Benedict (24 March 2017). "Liechtenstein, the country that's so small it keeps being invaded by its bigger neighbour". news.com.au. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

External links

- Official website (in German and English)

- Princely House of Liechtenstein

- Parliament of Liechtenstein

- Government of Liechtenstein

- Official tourism of Liechtenstein

- Statistics Office of Liechtenstein (in German)

- "Liechtenstein". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Liechtenstein from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Liechtenstein at Curlie

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Liechtenstein profile from BBC News

.svg.png)