Oceania

Oceania (UK: /ˌoʊsiˈɑːniə, ˌoʊʃi-, -ˈeɪn-/, US: /ˌoʊʃiˈæniə/ (![]()

.svg.png) An orthographic projection of geopolitical Oceania | |

| Area | 8,525,989 km2 (3,291,903 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population | 41,570,842 (2018, 6th)[1][2] |

| Population density | 4.19/km2 (10.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | $1.630 trillion (2018, 6th) |

| GDP per capita | $41,037 (2017, 2nd)[3] |

| Demonym | Oceanian |

| Countries | 14 (list)

Associated (2) (list)

|

| Dependencies | External (18) (list)

|

| Languages | 30 official

|

| Time zones | UTC+09 (Papua, Palau) to UTC-6 (Easter Island) (West to East) |

| Largest cities |

|

| UN M49 code | 009 – Oceania001 – World |

.svg.png) An orthographic projection of wider geographic Oceania. | |

| Area | 10,975,600 km2 (4,237,700 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population | 37.8 million (2010) |

| Demonym | Oceanian |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | External (19)

|

| Languages | 33 official

|

| Time zones | UTC+7 (Sumatra) to UTC-6 (Easter Island) |

| Largest cities | |

Oceania has a diverse mix of economies from the highly developed and globally competitive financial markets of Australia and New Zealand, which rank high in quality of life and human development index,[6][7] to the much less developed economies that belong to countries such as Kiribati and Tuvalu,[8] while also including medium-sized economies of Pacific islands such as Palau, Fiji and Tonga.[9] The largest and most populous country in Oceania is Australia, with Sydney being the largest city of both Oceania and Australia.[10]

The first settlers of Australia, New Guinea, and the large islands just to the east arrived more than 60,000 years ago.[11] Oceania was first explored by Europeans from the 16th century onward. Portuguese navigators, between 1512 and 1526, reached the Tanimbar Islands, some of the Caroline Islands and west Papua New Guinea. On his first voyage in the 18th century, James Cook, who later arrived at the highly developed Hawaiian Islands, went to Tahiti and followed the east coast of Australia for the first time.[12] The Pacific front saw major action during the Second World War, mainly between Allied powers the United States and Australia, and Axis power Japan.

The arrival of European settlers in subsequent centuries resulted in a significant alteration in the social and political landscape of Oceania. In more contemporary times there has been increasing discussion on national flags and a desire by some Oceanians to display their distinguishable and individualistic identity.[13] The rock art of Australian Aborigines is the longest continuously practiced artistic tradition in the world.[14] Puncak Jaya in Papua is the highest peak in Oceania at 4,884 metres.[15] Most Oceanian countries have a parliamentary representative democratic multi-party system, with tourism being a large source of income for the Pacific Islands nations.[16]

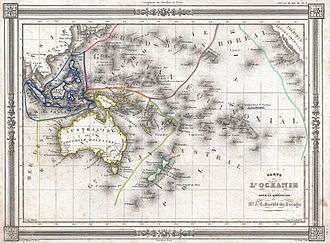

Definitions and extent

Definitions of Oceania vary; however, the islands at the geographic extremes of Oceania are generally considered to be the Bonin Islands, a politically integral part of Japan; Hawaii, a state of the United States; Clipperton Island, a possession of France; the Juan Fernández Islands, belonging to Chile; and Macquarie Island, belonging to Australia. (The United Nations has its own geopolitical definition of Oceania, but this consists of discrete political entities, and so excludes the Bonin Islands, Hawaii, Clipperton Island, and the Juan Fernández Islands, along with Easter Island.)[17]

The geographer Conrad Malte-Brun coined the French term Océanie c. 1812.[18] Océanie derives from the Latin word oceanus, and this from the Greek word ὠκεανός (ōkeanós), "ocean". The term Oceania is used because, unlike the other continental groupings, it is the ocean that links the parts of the region together.[19]

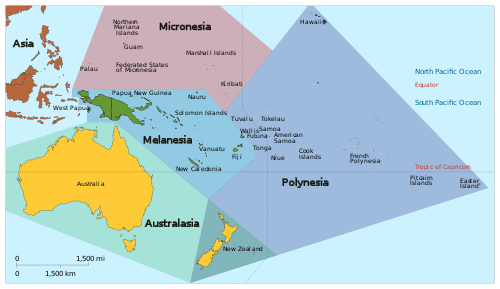

- Biogeographically, Oceania serves as a synonym for the Australasian realm and the Oceanian realm (Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia), with New Zealand forming the south-western corner of the Polynesian Triangle. Note that New Zealand may also be considered part of Australasia, despite forming a part of Polynesia.[20]

- As a biogeographic realm, Oceania includes all of Micronesia, Fiji, and all of Polynesia except New Zealand. New Zealand, along with New Guinea and nearby islands, Australia, eastern Indonesia, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia, constitute the separate Australasian realm.[21]

- In the geopolitical conception used by the United Nations, by the International Olympic Committee, and by many atlases, Oceania includes Australia and the nations of the Pacific from Papua New Guinea east, but not Indonesian New Guinea.[22]

In some countries (such as Brazil) however, Oceania is still regarded as a continent (Portuguese: continente) in the sense of "one of the parts of the world", and the concept of Australia as a continent does not exist.[23] Some geographers group the Australian continental plate with other islands in the Pacific into one "quasi-continent" called Oceania.[24]

History

Australia

.jpg)

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands who migrated from Africa to Asia around 70,000 years ago[25] and arrived in Australia around 50,000 years ago.[26] They are believed to be among the earliest human migrations out of Africa.[27] Although they likely migrated to Australia through Southeast Asia they are not demonstrably related to any known Asian or Polynesian population.[28] There is evidence of genetic and linguistic interchange between Australians in the far north and the Austronesian peoples of modern-day New Guinea and the islands, but this may be the result of recent trade and intermarriage.[29]

They reached Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago by migrating across a land bridge from the mainland that existed during the last ice age.[30] It is believed that the first early human migration to Australia was achieved when this landmass formed part of the Sahul continent, connected to the island of New Guinea via a land bridge.[31] The Torres Strait Islanders are indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands, which are at the northernmost tip of Queensland near Papua New Guinea.[32] The earliest definite human remains found in Australia are that of Mungo Man, which have been dated at about 40,000 years old.[33]

Melanesia

The original inhabitants of the group of islands now named Melanesia were likely the ancestors of the present-day Papuan-speaking people. Migrating from South-East Asia, they appear to have occupied these islands as far east as the main islands in the Solomon Islands archipelago, including Makira and possibly the smaller islands farther to the east.[34]

Particularly along the north coast of New Guinea and in the islands north and east of New Guinea, the Austronesian people, who had migrated into the area somewhat more than 3,000 years ago, came into contact with these pre-existing populations of Papuan-speaking peoples. In the late 20th century, some scholars theorized a long period of interaction, which resulted in many complex changes in genetics, languages, and culture among the peoples.[35]

Micronesia

.png)

Micronesia began to be settled several millennia ago, although there are competing theories about the origin and arrival of the first settlers. There are numerous difficulties with conducting archaeological excavations in the islands, due to their size, settlement patterns and storm damage. As a result, much evidence is based on linguistic analysis.[36]

The earliest archaeological traces of civilization have been found on the island of Saipan, dated to 1500 BC or slightly before. The ancestors of the Micronesians settled there over 4,000 years ago. A decentralized chieftain-based system eventually evolved into a more centralized economic and religious culture centered on Yap and Pohnpei.[37] The prehistories of many Micronesian islands such as Yap are not known very well.[38]

The first people of the Northern Mariana Islands navigated to the islands and discovered it at some period between 4000 BC to 2000 BC from South-East Asia. They became known as the Chamorros. Their language was named after them. The ancient Chamorro left a number of megalithic ruins, including Latte stone. The Refaluwasch, or Carolinian, people came to the Marianas in the 1800s from the Caroline Islands. Micronesian colonists gradually settled the Marshall Islands during the 2nd millennium BC, with inter-island navigation made possible using traditional stick charts.[39]

Polynesia

The Polynesian people are considered to be by linguistic, archaeological and human genetic ancestry a subset of the sea-migrating Austronesian people and tracing Polynesian languages places their prehistoric origins in the Malay Archipelago, and ultimately, in Taiwan. Between about 3000 and 1000 BCE speakers of Austronesian languages began spreading from Taiwan into Island South-East Asia,[40][41][42] as tribes whose natives were thought to have arrived through South China about 8,000 years ago to the edges of western Micronesia and on into Melanesia.

In the archaeological record there are well-defined traces of this expansion which allow the path it took to be followed and dated with some certainty. It is thought that by roughly 1400 BC,[43] "Lapita Peoples", so-named after their pottery tradition, appeared in the Bismarck Archipelago of north-west Melanesia.[44][45]

Easter Islanders claimed that a chief Hotu Matu'a[46] discovered the island in one or two large canoes with his wife and extended family.[47] They are believed to have been Polynesian. Around 1200, Tahitian explorers discovered and began settling the area. This date range is based on glottochronological calculations and on three radiocarbon dates from charcoal that appears to have been produced during forest clearance activities.[48] Moreover, a recent study which included radiocarbon dates from what is thought to be very early material suggests that the island was discovered and settled as recently as 1200.[49]

European exploration

From 1527 to 1595 a number of other large Spanish expeditions crossed the Pacific Ocean, leading to the arrival in Marshall Islands and Palau in the North Pacific, as well as Tuvalu, the Marquesas, the Solomon Islands archipelago, the Cook Islands and the Admiralty Islands in the South Pacific.[50]

In the quest for Terra Australis, Spanish explorations in the 17th century, such as the expedition led by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, sailed to Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos, and sailed the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea, named after navigator Luís Vaz de Torres. Willem Janszoon, made the first completely documented European landing in Australia (1606), in Cape York Peninsula.[51] Abel Janszoon Tasman circumnavigated and landed on parts of the Australian continental coast and discovered Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania), New Zealand in 1642, and Fiji islands.[52] He was the first known European explorer to reach these islands.[53]

On 23 April 1770 British explorer James Cook made his first recorded direct observation of indigenous Australians at Brush Island near Bawley Point.[54] On 29 April, Cook and crew made their first landfall on the mainland of the continent at a place now known as the Kurnell Peninsula. It is here that James Cook made first contact with an aboriginal tribe known as the Gweagal. His expedition became the first recorded Europeans to have encountered its eastern coastline of Australia.[55]

European settlement and colonisation

.png)

In 1789 the Mutiny on the Bounty against William Bligh led to several of the mutineers escaping the Royal Navy and settling on Pitcairn Islands, which later became a British colony. Britain also established colonies in Australia in 1788, New Zealand in 1840 and Fiji in 1872, with much of Oceania becoming part of the British Empire. The Gilbert Islands (now known as Kiribati) and the Ellice Islands (now known as Tuvalu) came under Britain's sphere of influence in the late 19th century.[56][57]

French Catholic missionaries arrived on Tahiti in 1834; their expulsion in 1836 caused France to send a gunboat in 1838. In 1842, Tahiti and Tahuata were declared a French protectorate, to allow Catholic missionaries to work undisturbed. The capital of Papeetē was founded in 1843.[58] On 24 September 1853, under orders from Napoleon III, Admiral Febvrier Despointes took formal possession of New Caledonia and Port-de-France (Nouméa) was founded 25 June 1854.[59]

The Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar landed in the Marshall Islands in 1529. They were named by Krusenstern, after English explorer John Marshall, who visited them together with Thomas Gilbert in 1788, en route from Botany Bay to Canton (two ships of the First Fleet). In 1905 the British government transferred some administrative responsibility over south-east New Guinea to Australia (which renamed the area "Territory of Papua"); and in 1906, transferred all remaining responsibility to Australia. The Marshall Islands were claimed by Spain in 1874. Germany established colonies in New Guinea in 1884, and Samoa in 1900. The United States also expanded into the Pacific, beginning with Baker Island and Howland Island in 1857, and with Hawaii becoming a U.S. territory in 1898. Disagreements between the US, Germany and UK over Samoa led to the Tripartite Convention of 1899.[60]

Modern history

.jpg)

One of the first land offensives in Oceania was the Occupation of German Samoa in August 1914 by New Zealand forces. The campaign to take Samoa ended without bloodshed after over 1,000 New Zealanders landed on the German colony. Australian forces attacked German New Guinea in September 1914. A company of Australians and a British warship besieged the Germans and their colonial subjects, ending with a German surrender.[61]

The attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters,[62][63] was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of 7 December 1941. The attack led to the United States' entry into World War II. The Japanese subsequently invaded New Guinea, Solomon Islands and other Pacific islands. The Japanese were turned back at the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Kokoda Track campaign before they were finally defeated in 1945. Some of the most prominent Oceanic battlegrounds were the Battle of Bita Paka, the Solomon Islands campaign, the Air raids on Darwin, the Kokada Track, and the Borneo campaign.[64][65] The United States fought the Battle of Guam from July 21 to August 10, 1944, to recapture the island from Japanese military occupation.[66]

Australia and New Zealand became dominions in the 20th century, adopting the Statute of Westminster Act in 1942 and 1947 respectively. In 1946, Polynesians were granted French citizenship and the islands' status was changed to an overseas territory; the islands' name was changed in 1957 to Polynésie Française (French Polynesia). Hawaii became a U.S. state in 1959. Fiji and Tonga became independent in 1970. On 1 May 1979, in recognition of the evolving political status of the Marshall Islands, the United States recognized the constitution of the Marshall Islands and the establishment of the Government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The South Pacific Forum was founded in 1971, which became the Pacific Islands Forum in 2000.[61]

Geography

Oceania was originally conceived as the lands of the Pacific Ocean, stretching from the Strait of Malacca to the coast of the Americas. It comprised four regions: Polynesia, Micronesia, Malaysia (now called the Malay Archipelago), and Melanesia.[67] Today, parts of three geological continents are included in the term "Oceania": Eurasia, Australia, and Zealandia, as well the non-continental volcanic islands of the Philippines, Wallacea, and the open Pacific.

Oceania extends to New Guinea in the west, the Bonin Islands in the northwest, the Hawaiian Islands in the northeast, Rapa Nui and Sala y Gómez Island in the east, and Macquarie Island in the south. Not included are the Pacific islands of Taiwan, the Ryukyu Islands, the Japanese archipelago, and the Maluku Islands, all on the margins of Asia, and the Aleutian Islands of North America. In its periphery, Oceania sprawls 28 degrees north to the Bonin Islands in the northern hemisphere, and 55 degrees south to Macquarie Island in the southern hemisphere.[68]

Oceanian islands are of four basic types: continental islands, high islands, coral reefs and uplifted coral platforms. High islands are of volcanic origin, and many contain active volcanoes. Among these are Bougainville, Hawaii, and Solomon Islands.[69]

Oceania is one of eight terrestrial ecozones, which constitute the major ecological regions of the planet. Related to these concepts are Near Oceania, that part of western Island Melanesia which has been inhabited for tens of millennia, and Remote Oceania which is more recently settled. Although the majority of the Oceanian islands lie in the South Pacific, a few of them are not restricted to the Pacific Ocean – Kangaroo Island and Ashmore and Cartier Islands, for instance, are situated in the Southern Ocean and Indian Ocean, respectively, and Tasmania's west coast faces the Southern Ocean.[70] The coral reefs of the South Pacific are low-lying structures that have built up on basaltic lava flows under the ocean's surface. One of the most dramatic is the Great Barrier Reef off northeastern Australia with chains of reef patches. A second island type formed of coral is the uplifted coral platform, which is usually slightly larger than the low coral islands. Examples include Banaba (formerly Ocean Island) and Makatea in the Tuamotu group of French Polynesia.[71][72]

.png)

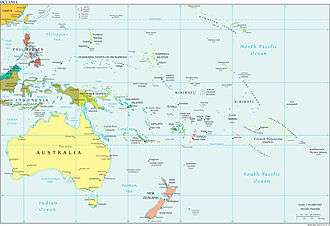

Regions

Micronesia, which lies north of the equator and west of the International Date Line, includes the Mariana Islands in the northwest, the Caroline Islands in the center, the Marshall Islands to the west and the islands of Kiribati in the southeast.[73][74]

Melanesia, to the southwest, includes New Guinea, the world's second largest island after Greenland and by far the largest of the Pacific islands. The other main Melanesian groups from north to south are the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands archipelago, Santa Cruz, Vanuatu, Fiji and New Caledonia.[75]

Polynesia, stretching from Hawaii in the north to New Zealand in the south, also encompasses Tuvalu, Tokelau, Samoa, Tonga and the Kermadec Islands to the west, the Cook Islands, Society Islands and Austral Islands in the center, and the Marquesas Islands, Tuamotu, Mangareva Islands, and Easter Island to the east.[76]

Australasia comprises Australia, New Zealand, the island of New Guinea, and neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. Along with India most of Australasia lies on the Indo-Australian Plate with the latter occupying the Southern area. It is flanked by the Indian Ocean to the west and the Southern Ocean to the south.[77][78]

Geology

The Pacific Plate, which makes up most of Oceania, is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At 103 million square kilometres (40,000,000 sq mi), it is the largest tectonic plate. The plate contains an interior hot spot forming the Hawaiian Islands.[79] It is almost entirely oceanic crust.[80] The oldest member disappearing by way of the plate tectonics cycle is early-Cretaceous (145 to 137 million years ago).[81]

Australia, being part of the Indo-Australian plate, is the lowest, flattest, and oldest landmass on Earth[82] and it has had a relatively stable geological history. Geological forces such as tectonic uplift of mountain ranges or clashes between tectonic plates occurred mainly in Australia's early history, when it was still a part of Gondwana. Australia is situated in the middle of the tectonic plate, and therefore currently has no active volcanism.[83] The geology of New Zealand is noted for its volcanic activity, earthquakes and geothermal areas because of its position on the boundary of the Australian Plate and Pacific Plates. Much of the basement rock of New Zealand was once part of the super-continent of Gondwana, along with South America, Africa, Madagascar, India, Antarctica and Australia. The rocks that now form the continent of Zealandia were nestled between Eastern Australia and Western Antarctica.[84]

The Australia-New Zealand continental fragment of Gondwana split from the rest of Gondwana in the late Cretaceous time (95–90 Ma). By 75 Ma, Zealandia was essentially separate from Australia and Antarctica, although only shallow seas might have separated Zealandia and Australia in the north. The Tasman Sea, and part of Zealandia then locked together with Australia to form the Australian Plate (40 Ma), and a new plate boundary was created between the Australian Plate and Pacific Plate.

Most islands in the Pacific are high islands (volcanic islands), such as, Easter Island, American Samoa and Fiji, among others, having peaks up to 1300 m rising abruptly from the shore.[85] The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were formed approximately 7 to 30 million years ago, as shield volcanoes over the same volcanic hotspot that formed the Emperor Seamounts to the north and the Main Hawaiian Islands to the south.[86] Hawaii's tallest mountain Mauna Kea is 4,205 m (13,796 ft) above mean sea level.[87]

Flora

%2C_Sunset.jpg)

The most diverse country of Oceania when it comes to the environment is Australia, with tropical rainforests in the north-east, mountain ranges in the south-east, south-west and east, and dry desert in the centre.[88] Desert or semi-arid land commonly known as the outback makes up by far the largest portion of land.[89] The coastal uplands and a belt of Brigalow grasslands lie between the coast and the mountains, while inland of the dividing range are large areas of grassland.[90] The northernmost point of the east coast is the tropical-rainforested Cape York Peninsula.[91][92][93][94][95]

Prominent features of the Australian flora are adaptations to aridity and fire which include scleromorphy and serotiny. These adaptations are common in species from the large and well-known families Proteaceae (Banksia), Myrtaceae (Eucalyptus – gum trees), and Fabaceae (Acacia – wattle). The flora of Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and New Caledonia is tropical dry forest, with tropical vegetation that includes palm trees, premna protrusa, psydrax odorata, gyrocarpus americanus and derris trifoliata.[96]

New Zealand's landscape ranges from the fjord-like sounds of the southwest to the tropical beaches of the far north. South Island is dominated by the Southern Alps. There are 18 peaks of more than 3000 metres (9800 ft) in the South Island. All summits over 2,900 m are within the Southern Alps, a chain that forms the backbone of the South Island; the highest peak of which is Aoraki / Mount Cook, at 3,754 metres (12,316 ft). Earthquakes are common, though usually not severe, averaging 3,000 per year.[97] There is a wide variety of native trees, adapted to all the various micro-climates in New Zealand.[98]

In Hawaii, one endemic plant, Brighamia, now requires hand-pollination because its natural pollinator is presumed to be extinct.[99] The two species of Brighamia – B. rockii and B. insignis – are represented in the wild by around 120 individual plants. To ensure these plants set seed, biologists rappel down 910-metre (3,000 ft) cliffs to brush pollen onto their stigmas.[100]

Fauna

_in_the_Norfolk_Island.jpg)

The aptly-named Pacific kingfisher is found in the Pacific Islands,[102] as is the Red-vented bulbul,[103] Polynesian starling,[104] Brown goshawk,[105]Pacific Swallow[106] and the Cardinal myzomela, among others.[107] Birds breeding on Pitcairn include the fairy tern, common noddy and red-tailed tropicbird. The Pitcairn reed warbler, endemic to Pitcairn Island, was added to the endangered species list in 2008.[108]

Native to Hawaii is the Hawaiian crow, which has been extinct in the wild since 2002.[109] The brown tree snake is native to northern and eastern coasts of Australia, Papua New Guinea, Guam and Solomon Islands.[110] Native to Australia, New Guinea and proximate islands are birds of paradise, honeyeaters, Australasian treecreeper, Australasian robin, kingfishers, butcherbirds and bowerbirds.[111][112]

A unique feature of Australia's fauna is the relative scarcity of native placental mammals, and dominance of the marsupials – a group of mammals that raise their young in a pouch, including the macropods, possums and dasyuromorphs. The passerines of Australia, also known as songbirds or perching birds, include wrens, the magpie group, thornbills, corvids, pardalotes, lyrebirds.[113] Predominant bird species in the country include the Australian magpie, Australian raven, the pied currawong, crested pigeons and the laughing kookaburra.[114] The koala, emu, platypus and kangaroo are national animals of Australia,[115] and the Tasmanian devil is also one of the well-known animals in the country.[116] The goanna is a predatory lizard native to the Australian mainland.[117]

The birds of New Zealand evolved into an avifauna that included a large number of endemic species. As an island archipelago New Zealand accumulated bird diversity and when Captain James Cook arrived in the 1770s he noted that the bird song was deafening. The mix includes species with unusual biology such as the kakapo which is the world's only flightless, nocturnal, lek breeding parrot, but also many species that are similar to neighboring land areas. Some of the more well known and distinctive bird species in New Zealand are the kiwi, kea, takahe, kakapo, mohua, tui and the bellbird.[118] The tuatara is a notable reptile endemic to New Zealand.[119]

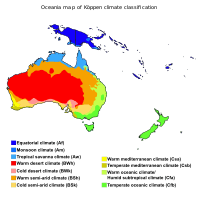

Climate

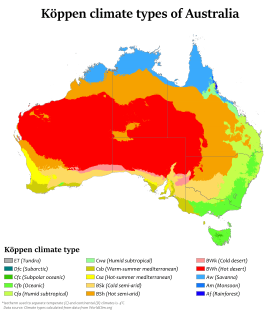

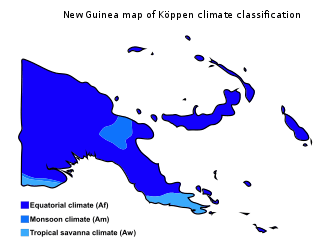

The Pacific Islands are ruled by a tropical rainforest and tropical savanna climate. In the tropical and subtropical Pacific, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) affects weather conditions.[120] In the tropical western Pacific, the monsoon and the related wet season during the summer months contrast with dry winds in the winter which blow over the ocean from the Asian landmass.[121] November is the only month in which all the tropical cyclone basins are active.[122]

To the southwest of the region, in the Australian landmass, the climate is mostly desert or semi-arid, with the southern coastal corners having a temperate climate, such as oceanic and humid subtropical climate in the east coast and Mediterranean climate in the west. The northern parts of the country have a tropical climate.[123] Snow falls frequently on the highlands near the east coast, in the states of Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and in the Australian Capital Territory.[124]

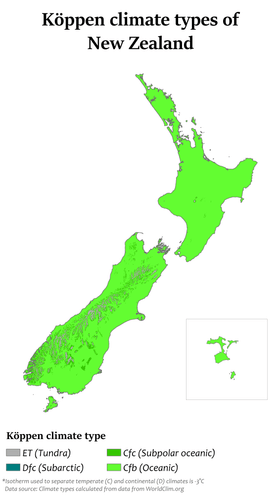

Most regions of New Zealand belong to the temperate zone with a maritime climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb) characterised by four distinct seasons. Conditions vary from extremely wet on the West Coast of the South Island to almost semi-arid in Central Otago and subtropical in Northland.[125][126] Snow falls in New Zealand's South Island and at higher altitudes in the North Island. It is extremely rare at sea level in the North Island.[127]

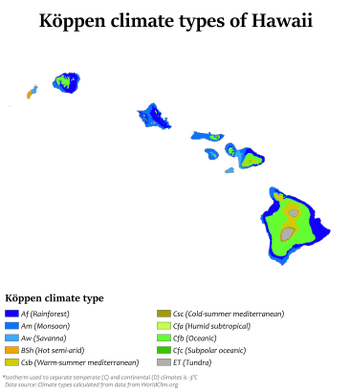

Hawaii, although being in the tropics, experiences many different climates, depending on latitude and its geography. The island of Hawaii for example hosts 4 (out of 5 in total) climate groups on a surface as small as 10,430 km2 (4,028 sq mi) according to the Köppen climate types: tropical, arid, temperate and polar. The Hawaiian Islands receive most of their precipitation during the winter months (October to April).[128] A few islands in the northwest, such as Guam, are susceptible to typhoons in the wet season.[129]

The highest recorded temperature in Oceania occurred in Oodnadatta, South Australia (2 January 1960), where the temperature reached 50.7 °C (123.3 °F).[130] The lowest temperature ever recorded in Oceania was −25.6 °C (−14.1 °F), at Ranfurly in Otago in 1903, with a more recent temperature of −21.6 °C (−6.9 °F) recorded in 1995 in nearby Ophir.[131] Pohnpei of the Senyavin Islands in Micronesia is the wettest settlement in Oceania, and one of the wettest places on earth, with annual recorded rainfall exceeding 7,600 mm (300 in) each year in certain mountainous locations.[132] The Big Bog on the island of Maui is the wettest place, receiving an average 10,271 mm (404.4 in) each year.[133]

Australia

Australia Hawaii

Hawaii New Zealand

New Zealand Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea Australasia and adjacent islands

Australasia and adjacent islands

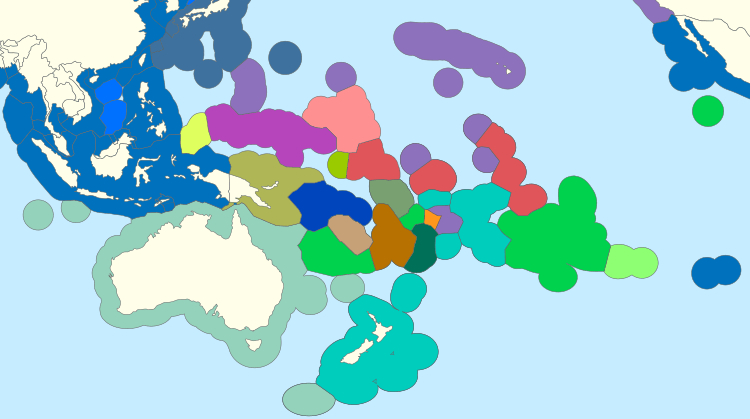

Demographics

The linked map below shows the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of the islands of Oceania and neighbouring areas, as a guide to the following table (there are few land boundaries that can be drawn on a map of the Pacific at this scale).

Vela

The demographic table below shows the subregions and countries of geopolitical Oceania. The countries and territories in this table are categorised according to the scheme for geographic subregions used by the United Nations. The information shown follows sources in cross-referenced articles; where sources differ, provisos have been clearly indicated. These territories and regions are subject to various additional categorisations, depending on the source and purpose of each description.

| Arms | Flag | Name of region, followed by countries[134] | Area (km2) |

Population (2018)[1][2] |

Population density (per km2) |

Capital | ISO 3166-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australasia[135] | |||||||

| Ashmore and Cartier Islands (Australia) | 199 | ||||||

| Australia | 7,686,850 | 24,898,152 | 3.1 | Canberra | AU | ||

| Coral Sea Islands (Australia) | 10 | 4 | 0.4 | ||||

| New Zealand[136] | 268,680 | 4,743,131 | 17.3 | Wellington | NZ | ||

| Norfolk Island (Australia) | 35 | 2,302 | 65.8 | Kingston | NF | ||

| Australasia (total) | 7,955,774 | 28,788,987 | 3.6 | ||||

| Melanesia[137] | |||||||

| Fiji | 18,270 | 883,483 | 49.2 | Suva | FJ | ||

| New Caledonia (France) | 19,060 | 279,993 | 14.3 | Nouméa | NC | ||

| Papua (Indonesia)[138][139] | 319,036 | 3,486,432 | 10.9 | Jayapura | |||

| West Papua (Indonesia)[140][141] | 140,375 | 760,855 | 5.4 | Manokwari | |||

| Papua New Guinea[142] | 462,840 | 8,606,323 | 17.5 | Port Moresby | PG | ||

| Solomon Islands | 28,450 | 652,857 | 21.1 | Honiara | SB | ||

| Vanuatu | 12,200 | 292,680 | 22.2 | Port Vila | VU | ||

| Melanesia (total) | 1,000,231 | 14,373,536 | 14.4 | ||||

| Micronesia | |||||||

| Federated States of Micronesia | 702 | 112,640 | 149.5 | Palikir | FM | ||

| Guam (United States) | 549 | 165,768 | 296.7 | Hagåtña | GU | ||

| Kiribati | 811 | 115,847 | 141.1 | South Tarawa | KI | ||

| Marshall Islands | 181 | 58,413 | 293.2 | Majuro | MH | ||

| Nauru | 21 | 10,670 | 540.3 | Yaren (de facto) | NR | ||

| Northern Mariana Islands (United States) | 477 | 56,882, | 115.4 | Saipan | MP | ||

| Palau | 458 | 17,907 | 46.9 | Ngerulmud[143] | PW | ||

| Wake Island (United States) | 2 | 150 | 75 | Wake Island | UM | ||

| Micronesia (total) | 3,201 | 523,317 | 163.5 | ||||

| Polynesia | |||||||

| American Samoa (United States) | 199 | 55,465 | 279.4 | Pago Pago, Fagatogo[144] | AS | ||

| Cook Islands (New Zealand) | 240 | 17,518 | 72.4 | Avarua | CK | ||

| Easter Island (Chile) | 164 | 5,761 | 35.1 | Hanga Roa | CL | ||

| French Polynesia (France) | 4,167 | 277,679 | 67.2 | Papeete | PF | ||

| Hawaii (United States) | 16,636 | 1,360,301 | 81.8 | Honolulu | US | ||

| Niue (New Zealand) | 260 | 1,620 | 6.2 | Alofi | NU | ||

| Pitcairn Islands (United Kingdom) | 47 | 47 | 1 | Adamstown | PN | ||

| Samoa | 2,944 | 196,129 | 66.3 | Apia | WS | ||

| Tokelau (New Zealand) | 10 | 1,319 | 128.2 | Nukunonu | TK | ||

| Tonga | 748 | 103,197 | 143.2 | Nukuʻalofa | TO | ||

| Tuvalu | 26 | 11,508 | 426.8 | Funafuti | TV | ||

| Wallis and Futuna (France) | 274 | 11,661 | 43.4 | Mata-Utu | WF | ||

| Polynesia (total) | 25,715 | 2,047,444 | 79.6 | ||||

| Total | 8,919,530 | 47,178,430 | 5.1 | ||||

| Total minus mainland Australia | 1,232,680 | 22,280,278 | 16.6 | ||||

Largest city for regions

- Australasia (metro, urban or proper largest city: Sydney)

- Melanesia (metro, urban or proper largest city: Port Moresby)

- Micronesia (metro, urban or proper largest city: Tarawa)

- Polynesia (metro, urban or proper largest city: Auckland)

Urban areas

Religion

The predominant religion in Oceania is Christianity (73%).[150][151] A 2011 survey found that 92% in Melanesia,[150] 93% in Micronesia[150] and 96% in Polynesia described themselves as Christians.[150] Traditional religions are often animist, and prevalent among traditional tribes is the belief in spirits (masalai in Tok Pisin) representing natural forces.[152] In the 2018 census, 37% of New Zealanders affiliated themselves with Christianity and 48% declared no religion.[153] In the 2016 Census, 52% of the Australian population declared some variety of Christianity and 30% stated "no religion".[154]

In recent Australian and New Zealand censuses, large proportions of the population say they belong to "no religion" (which includes atheism, agnosticism, deism, secular humanism). In Tonga, everyday life is heavily influenced by Polynesian traditions and especially by the Christian faith. The Ahmadiyya mosque in Marshall Islands is the only mosque in Micronesia.[155] Another one in Tuvalu belongs to the same sect. The Bahá'í House of Worship in Tiapapata, Samoa, is one of seven designations administered in the Bahá'í Faith.

Other religions in the region include Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism, which are prominent minority religions in Australia and New Zealand. Judaism, Sikhism and Jainism are also present. Sir Isaac Isaacs was the first Australian born Governor General of Australia and was the first Jewish vice-regal representative in the British Empire.[156] Prince Philip Movement is followed around Yaohnanen village on the southern island of Tanna in Vanuatu.

Languages

Native languages of Oceania fall into three major geographic groups:

- The large Austronesian language family, with such languages as Malay (Indonesian), and Oceanic languages such as Gilbertese, Fijian, Maori or Hawaiian

- The Aboriginal Australian languages, including the large Pama–Nyungan family

- The Papuan languages of New Guinea and neighbouring islands, including the large Trans–New Guinea family

Colonial languages include English in Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, and many other territories; French in New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, and Vanuatu, Japanese in the Bonin Islands, Spanish on Galápagos Islands and Easter Island. There are also Creoles formed from the interaction of Malay or the colonial languages with indigenous languages, such as Tok Pisin, Bislama, Chavacano, various Malay trade and creole languages, Hawaiian Pidgin, Norfuk, and Pitkern. Contact between Austronesian and Papuan resulted in several instances in mixed languages such as Maisin.

Immigrants brought their own languages to the region, such as Mandarin, Italian, Arabic, Polish, Hindi, German, Spanish, Korean, Cantonese and Greek, among others, namely in Australia and New Zealand,[157] or Fiji Hindi in Fiji.

Immigration

The most multicultural areas in Oceania, which have a high degree of immigration, are Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii. Since 1945, more than 7 million people have settled in Australia. From the late 1970s, there was a significant increase in immigration from Asian and other non-European countries, making Australia a multicultural country.[158]

Sydney is the most multicultural city in Oceania, having more than 250 different languages spoken with about 40 percent of residents speaking a language other than English at home.[159] Furthermore, 36 percent of the population reported having been born overseas, with top countries being Italy, Lebanon, Vietnam and Iraq, among others.[160][161] Melbourne is also fairly multicultural, having the largest Greek-speaking population outside of Europe,[162] and the second largest Asian population in Australia after Sydney.[163][164][165]

European migration to New Zealand provided a major influx following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. Subsequent immigration has been chiefly from the British Isles, but also from continental Europe, the Pacific, The Americas and Asia.[166][167] Auckland is home to over half (51.6 percent) of New Zealand's overseas born population, including 72 percent of the country's Pacific Island-born population, 64 percent of its Asian-born population, and 56 percent of its Middle Eastern and African born population.[168]

Hawaii is a majority-minority state.[169] Chinese workers on Western trading ships settled in Hawaii starting in 1789. In 1820, the first American missionaries arrived to preach Christianity and teach the Hawaiians Western ways.[170] As of 2015, a large proportion of Hawaii's population have Asian ancestry – especially Filipino, Japanese, Korean and Chinese. Many are descendants of immigrants brought to work on the sugarcane plantations in the mid-to-late 19th century. Almost 13,000 Portuguese immigrants had arrived by 1899; they also worked on the sugarcane plantations.[171] Puerto Rican immigration to Hawaii began in 1899 when Puerto Rico's sugar industry was devastated by two hurricanes, causing a worldwide shortage of sugar and a huge demand for sugar from Hawaii.[172]

Between 2001 and 2007 Australia's Pacific Solution policy transferred asylum seekers to several Pacific nations, including the Nauru detention centre. Australia, New Zealand and other nations took part in the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands between 2003 and 2017 after a request for aid.[173]

Archaeogenetics

Archaeology, linguistics, and existing genetic studies indicate that Oceania was settled by two major waves of migration. The first migration Australo-Melanesian) took place approximately 40 to 80 thousand years ago, and these migrants, Papuans, colonised much of Near Oceania. Approximately 3.5 thousand years ago, a second expansion of Austronesian speakers arrived in Near Oceania, and the descendants of these people spread to the far corners of the Pacific, colonising Remote Oceania.[174]

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) studies quantify the magnitude of the Austronesian expansion and demonstrate the homogenising effect of this expansion. With regards to Papuan influence, autochthonous haplogroups support the hypothesis of a long history in Near Oceania, with some lineages suggesting a time depth of 60 thousand years. Santa Cruz, a population located in Remote Oceania, is an anomaly with extreme frequencies of autochthonous haplogroups of Near Oceanian origin.[174]

Large areas of New Guinea are unexplored by scientists and anthropologists due to extensive forestation and mountainous terrain. Known indigenous tribes in Papua New Guinea have very little contact with local authorities aside from the authorities knowing who they are. Many remain preliterate and, at the national or international level, the names of tribes and information about them is extremely hard to obtain. The Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua on the island of New Guinea are home to an estimated 44 uncontacted tribal groups.[175]

Economy

Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand are the only developed nations in the region, although the economy of Australia is by far the largest and most dominant economy in the region and one of the largest in the world. Australia's per-capita GDP is higher than that of the UK, Canada, Germany, and France in terms of purchasing power parity.[176] New Zealand is also one of the most globalised economies and depends greatly on international trade.[177][178]

The Australian Securities Exchange in Sydney is the largest stock exchange in Australia and in the South Pacific.[179] New Zealand is the 53rd-largest national economy in the world measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP) and 68th-largest in the world measured by purchasing power parity (PPP). In 2012, Australia was the 12th largest national economy by nominal GDP and the 19th-largest measured by PPP-adjusted GDP.[180]

Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranks Sydney tenth in the world in terms of quality of living,[181] making it one of the most livable cities.[182] It is classified as an Alpha+ World City by GaWC.[183][184] Melbourne also ranked highly in the world's most liveable city list,[185] and is a leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region.[186][187] Auckland and Wellington, in New Zealand, are frequently ranked among the world's most liveable cities with Auckland being ranked 3rd according to the Mercer Quality of Living Survey.[188][189]

The majority of people living in Australia and to a lesser extent, New Zealand work in mining, electrical and manufacturing sectors also. Australia boasts the largest amount of manufacturing in the region, producing cars, electrical equipment, machinery and clothes.

Pacific Islands

The overwhelming majority of people living in the Pacific islands work in the service industry which includes tourism, education and financial services. Oceania's largest export markets include Japan, China, the United States and South Korea. The smallest Pacific nations rely on trade with Australia, New Zealand and the United States for exporting goods and for accessing other products. Australia and New Zealand's trading arrangements are known as Closer Economic Relations. Australia and New Zealand, along with other countries, are members of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the East Asia Summit (EAS), which may become trade blocs in the future particularly EAS.

The main produce from the Pacific is copra or coconut, but timber, beef, palm oil, cocoa, sugar and ginger are also commonly grown across the tropics of the Pacific. Fishing provides a major industry for many of the smaller nations in the Pacific, although many fishing areas are exploited by other larger countries, namely Japan. Natural Resources, such as lead, zinc, nickel and gold, are mined in Australia and Solomon Islands. Oceania's largest export markets include Japan, China, the United States, India, South Korea and the European Union.

Endowed with forest, mineral, and fish resources, Fiji is one of the most developed of the Pacific island economies, though it remains a developing country with a large subsistence agriculture sector.[190] Agriculture accounts for 18% of gross domestic product, although it employed some 70% of the workforce as of 2001. Sugar exports and the growing tourist industry are the major sources of foreign exchange. Sugar cane processing makes up one-third of industrial activity. Coconuts, ginger, and copra are also significant.

The history of Hawaii's economy can be traced through a succession of dominant industries; sandalwood,[191] whaling,[192] sugarcane, pineapple, the military, tourism and education.[193] Hawaiian exports include food and clothing. These industries play a small role in the Hawaiian economy, due to the shipping distance to viable markets, such as the West Coast of the contiguous U.S. The state's food exports include coffee, macadamia nuts, pineapple, livestock, sugarcane and honey.[194] As of 2015, Honolulu was ranked high on world livability rankings, and was also ranked as the 2nd safest city in the U.S.[195][196]

Tourism

Tourists mostly come from Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. Fiji currently draws almost half a million tourists each year; more than a quarter from Australia. This contributes $1 billion or more since 1995 to Fiji's economy but the Government of Fiji islands underestimate these figures due to the invisible economy inside the tourism industry.

Vanuatu is widely recognised as one of the premier vacation destinations for scuba divers wishing to explore coral reefs of the South Pacific region. Tourism has been promoted, in part, by Vanuatu being the site of several reality-TV shows. The ninth season of the reality TV series Survivor was filmed on Vanuatu, entitled Survivor: Vanuatu – Islands of Fire. Two years later, Australia's Celebrity Survivor was filmed at the same location used by the US version.[197]

Tourism in Australia is an important component of the Australian economy. In the financial year 2014/15, tourism represented 3% of Australia's GDP contributing A$47.5 billion to the national economy.[198] In 2015, there were 7.4 million visitor arrivals.[199] Popular Australian destinations include the Sydney Harbour (Sydney Opera House, Sydney Harbour Bridge, Royal Botanic Garden, etc.), Gold Coast (theme parks such as Warner Bros. Movie World, Dreamworld and Sea World), Walls of Jerusalem National Park and Mount Field National Park in Tasmania, Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne, the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, The Twelve Apostles in Victoria, Uluru (Ayers Rock) and the Australian outback.[200]

Tourism in New Zealand contributes NZ$7.3 billion (or 4%) of the country's GDP in 2013, as well as directly supporting 110,800 full-time equivalent jobs (nearly 6% of New Zealand's workforce). International tourist spending accounted for 16% of New Zealand's export earnings (nearly NZ$10 billion). International and domestic tourism contributes, in total, NZ$24 billion to New Zealand's economy every year. Tourism New Zealand, the country's official tourism agency, is actively promoting the country as a destination worldwide.[201] Milford Sound in South Island is acclaimed as New Zealand's most famous tourist destination.[202]

In 2003 alone, according to state government data, there were over 6.4 million visitors to the Hawaiian Islands with expenditures of over $10.6 billion.[203] Due to the mild year-round weather, tourist travel is popular throughout the year. In 2011, Hawaii saw increasing arrivals and share of foreign tourists from Canada, Australia and China increasing 13%, 24% and 21% respectively from 2010.[204]

Politics

Australia

Australia is a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy[205] with Elizabeth II at its apex as the Queen of Australia, a role that is distinct from her position as monarch of the other Commonwealth realms. The Queen is represented in Australia by the Governor-General at the federal level and by the Governors at the state level, who by convention act on the advice of her ministers.[206][207] There are two major political groups that usually form government, federally and in the states: the Australian Labor Party and the Coalition which is a formal grouping of the Liberal Party and its minor partner, the National Party.[208][209] Within Australian political culture, the Coalition is considered centre-right and the Labor Party is considered centre-left.[210] The Australian Defence Force is by far the largest military force in Oceania.[211]

New Zealand

New Zealand is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy,[212] although its constitution is not codified.[213] Elizabeth II is the Queen of New Zealand and the head of state.[214] The Queen is represented by the Governor-General, whom she appoints on the advice of the Prime Minister.[215] The New Zealand Parliament holds legislative power and consists of the Queen and the House of Representatives.[216] A parliamentary general election must be called no later than three years after the previous election.[217] New Zealand is identified as one of the world's most stable and well-governed states,[218][219] with high government transparency and among the lowest perceived levels of corruption.[220]

Pacific Islands

In Samoan politics, the Prime Minister of Samoa is the head of government. The 1960 constitution, which formally came into force with independence from New Zealand in 1962, builds on the British pattern of parliamentary democracy, modified to take account of Samoan customs. The national government (malo) generally controls the legislative assembly.[221] Politics of Tonga takes place in a framework of a constitutional monarchy, whereby the King is the Head of State.

Fiji has a multiparty system with the Prime Minister of Fiji as head of government. The executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Parliament of Fiji. Fiji's Head of State is the President. He is elected by Parliament of Fiji after nomination by the Prime Minister or the Leader of the Opposition, for a three-year term.

In the politics of Papua New Guinea the Prime Minister is the head of government. In Kiribati, a Parliamentary regime, the President of Kiribati is the head of state and government, and of a multi-party system.

New Caledonia remains an integral part of the French Republic. Inhabitants of New Caledonia are French citizens and carry French passports. They take part in the legislative and presidential French elections. New Caledonia sends two representatives to the French National Assembly and two senators to the French Senate.

Hawaii is dominated by the Democratic Party. As codified in the Constitution of Hawaii, there are three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. The governor is elected statewide. The lieutenant governor acts as the Secretary of State. The governor and lieutenant governor oversee twenty agencies and departments from offices in the State Capitol.

Culture

Australia

Since 1788, the primary influence behind Australian culture has been Anglo-Celtic Western culture, with some Indigenous influences.[223][224] The divergence and evolution that has occurred in the ensuing centuries has resulted in a distinctive Australian culture.[225][226] Since the mid-20th century, American popular culture has strongly influenced Australia, particularly through television and cinema.[227] Other cultural influences come from neighbouring Asian countries, and through large-scale immigration from non-English-speaking nations.[227][228] The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), the world's first feature length film, spurred a boom in Australian cinema during the silent film era.[229][230] The Australian Museum in Sydney and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne are the oldest and largest museums in Oceania.[231][232] The city's New Year's Eve celebrations are the largest in Oceania.[233]

Australia is also known for its cafe and coffee culture in urban centres.[234] Australia and New Zealand were responsible for the flat white coffee. Most Indigenous Australian tribal groups subsisted on a simple hunter-gatherer diet of native fauna and flora, otherwise called bush tucker.[235][236] The first settlers introduced British food to the continent, much of which is now considered typical Australian food, such as the Sunday roast.[237][238] Multicultural immigration transformed Australian cuisine; post-World War II European migrants, particularly from the Mediterranean, helped to build a thriving Australian coffee culture, and the influence of Asian cultures has led to Australian variants of their staple foods, such as the Chinese-inspired dim sim and Chiko Roll.[239]

Hawaii

The music of Hawaii includes traditional and popular styles, ranging from native Hawaiian folk music to modern rock and hip hop. Hawaii's musical contributions to the music of the United States are out of proportion to the state's small size. Styles such as slack-key guitar are well known worldwide, while Hawaiian-tinged music is a frequent part of Hollywood soundtracks. Hawaii also made a major contribution to country music with the introduction of the steel guitar.[240] The Hawaiian religion is polytheistic and animistic, with a belief in many deities and spirits, including the belief that spirits are found in non-human beings and objects such as animals, the waves, and the sky.[241]

The cuisine of Hawaii is a fusion of many foods brought by immigrants to the Hawaiian Islands, including the earliest Polynesians and Native Hawaiian cuisine, and American, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Polynesian and Portuguese origins. Native Hawaiian musician and Hawaiian sovereignty activist Israel Kamakawiwoʻole, famous for his medley of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World", was named "The Voice of Hawaii" by NPR in 2010 in its 50 great voices series.[242]

New Zealand

New Zealand as a culture is a Western culture, which is influenced by the cultural input of the indigenous Māori and the various waves of multi-ethnic migration which followed the British colonisation of New Zealand. Māori people constitute one of the major cultures of Polynesia. The country has been broadened by globalisation and immigration from the Pacific Islands, East Asia and South Asia.[244] New Zealand marks two national days of remembrance, Waitangi Day and ANZAC Day, and also celebrates holidays during or close to the anniversaries of the founding dates of each province.[245]

The New Zealand recording industry began to develop from 1940 onwards and many New Zealand musicians have obtained success in Britain and the United States.[246] Some artists release Māori language songs and the Māori tradition-based art of kapa haka (song and dance) has made a resurgence.[247] The country's diverse scenery and compact size, plus government incentives,[248] have encouraged some producers to film big budget movies in New Zealand, including Avatar, The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, The Chronicles of Narnia, King Kong and The Last Samurai.[249]

The national cuisine has been described as Pacific Rim, incorporating the native Māori cuisine and diverse culinary traditions introduced by settlers and immigrants from Europe, Polynesia and Asia.[250] New Zealand yields produce from land and sea – most crops and livestock, such as maize, potatoes and pigs, were gradually introduced by the early European settlers.[251] Distinctive ingredients or dishes include lamb, salmon, koura (crayfish),[252] dredge oysters, whitebait, paua (abalone), mussels, scallops, pipi and tuatua (both are types of New Zealand shellfish),[253] kumara (sweet potato), kiwifruit, tamarillo and pavlova (considered a national dish).[254][250]

Samoa

The fa'a Samoa, or traditional Samoan way, remains a strong force in Samoan life and politics. Despite centuries of European influence, Samoa maintains its historical customs, social and political systems, and language. Cultural customs such as the Samoa 'ava ceremony are significant and solemn rituals at important occasions including the bestowal of matai chiefly titles. Items of great cultural value include the finely woven 'ie toga.

The Samoan word for dance is siva, which consists of unique gentle movements of the body in time to music and which tell a story. Samoan male dances can be more snappy.[255] The sasa is also a traditional dance where rows of dancers perform rapid synchronised movements in time to the rhythm of wooden drums (pate) or rolled mats. Another dance performed by males is called the fa'ataupati or the slap dance, creating rhythmic sounds by slapping different parts of the body. As with other Polynesian cultures (Hawaiian, Tahitian and Māori) with significant and unique tattoos, Samoans have two gender specific and culturally significant tattoos.[256]

Arts

The artistic creations of native Oceanians varies greatly throughout the cultures and regions. The subject matter typically carries themes of fertility or the supernatural. Petroglyphs, Tattooing, painting, wood carving, stone carving and textile work are other common art forms.[257] Art of Oceania properly encompasses the artistic traditions of the people indigenous to Australia and the Pacific Islands.[258] These early peoples lacked a writing system, and made works on perishable materials, so few records of them exist from this time.[259]

Indigenous Australian rock art is the oldest and richest unbroken tradition of art in the world, dating as far back as 60,000 years and spread across hundreds of thousands of sites.[260][261] These rock paintings served several functions. Some were used in magic, others to increase animal populations for hunting, while some were simply for amusement.[262] Sculpture in Oceania first appears on New Guinea as a series of stone figures found throughout the island, but mostly in mountainous highlands. Establishing a chronological timeframe for these pieces in most cases is difficult, but one has been dated to 1500 BC.[263]

By 1500 BC the Lapita culture, descendants of the second wave, would begin to expand and spread into the more remote islands. At around the same time, art began to appear in New Guinea, including the earliest examples of sculpture in Oceania. Starting around 1100 AD, the people of Easter Island would begin construction of nearly 900 moai (large stone statues). At about 1200 AD, the people of Pohnpei, a Micronesian island, would embark on another megalithic construction, building Nan Madol, a city of artificial islands and a system of canals.[264] Hawaiian art includes wood carvings, feather work, petroglyphs, bark cloth (called kapa in Hawaiian and tapa elsewhere in the Pacific) and tattoos. Native Hawaiians had neither metal nor woven cloth.[265]

Sport

Rugby union is one of the region's most prominent sports,[266] and is the national sport of New Zealand, Samoa, Fiji and Tonga. The most popular sport in Australia is cricket, the most popular sport among Australian women is netball, while Australian rules football is the most popular sport in terms of spectatorship and television ratings.[267][268][269] Rugby is the most popular sport among New Zealanders.[270] In Papua New Guinea, the most popular sport is Rugby league.[271]

Australian rules football is the national sport in Nauru[272] and is the most popular football code in Australia in terms of attendance.[273] It has a large following in Papua New Guinea, where it is the second most popular sport after Rugby League.[274][275][276] It attracts significant attention across New Zealand and the Pacific Islands.[277] Fiji's sevens team is one of the most successful in the world, as is New Zealand's.[278]

Currently Vanuatu is the only country in Oceania to call association football its national sport. However, it is also the most popular sport in Kiribati, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu, and has a significant (and growing) popularity in Australia. In 2006 Australia joined the Asian Football Confederation and qualified for the 2010, 2014 and 2018 World Cups as an Asian entrant.[279]

Australia has hosted two Summer Olympics: Melbourne 1956 and Sydney 2000. Also, Australia has hosted five editions of the Commonwealth Games (Sydney 1938, Perth 1962, Brisbane 1982, Melbourne 2006, Gold Coast 2018). Meanwhile, New Zealand has hosted the Commonwealth Games three times: Auckland 1950, Christchurch 1974 and Auckland 1990. The Pacific Games (formerly known as the South Pacific Games) is a multi-sport event, much like the Olympics on a much smaller scale, with participation exclusively from countries around the Pacific. It is held every four years and began in 1963. Australia and New Zealand competed in the games for the first time in 2015.[280]

See also

References

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "United Nations Statistics Division – National Accounts". unstats.un.org.

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- For a history of the term, see Douglas & Ballard (2008) Foreign bodies: Oceania and the science of race 1750–1940

- "Australia: World Audit Democracy Profile". WorldAudit.org. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- "Rankings on Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Kiribati: 2011 Article IV Consultation-Staff Report, Informational Annexes, Debt Sustainability Analysis, Public Information Notice on the Executive Board Discussion, and Statement by the Executive Director for Kiribati". International Monetary Fund Country Report No. 11/113. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- "2011 Human Development Report: Pacific Islands' progress jeopardized by inequalities and environmental threats". UNDP. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Fast facts about Australia". Archived from the original on 20 August 2003. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/2019/02/aboriginal-australians

- "Secret Instructions to Captain Cook, 30 June 1768" (PDF). National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- Dimensions of Australian Society, Ian McAllister – 1994, p. 333

- "Oceanic art", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition 2006.

- MacKay (1864, 1885) Elements of Modern Geography, p. 283

- Drage, Jean (1994). New Politics in the South pacific. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific. p. 162. ISBN 978-982-02-0115-6.

- "Countries or areas / geographical regions". United Nations. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- "Oceania". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lyons, Paul (2006). American Pacificism: Oceania in the U.S. Imagination. p. 30. ISBN 9781134264155.

- Udvardy. 1975. A classification of the biogeographical provinces of the world

- Son, George Philip (2003). Philip's E.A.E.P Atlas. East African Publishers. p. 79. ISBN 978-9966-25-125-1.

- Lewis, Martin W.; Kären E. Wigen (1997). The Myth of Continents: a Critique of Metageography. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-520-20742-4.

Interestingly enough, the answer [from a scholar who sought to calculate the number of continents] conformed almost precisely to the conventional list: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Oceania (Australia plus New Zealand), Africa, and Antarctica.

- https://atlasescolar.ibge.gov.br/images/atlas/mapas_mundo/mundo_034_divisao_continentes.pdf

- Lewis & Wigen, The Myth of Continents (1997), p. 40: "The joining of Australia with various Pacific islands to form the quasi continent of Oceania ... "

- Rasmussen, Morten; Guo, Xiaosen; Wang, Yong; Lohmueller, Kirk E.; Rasmussen, Simon; Albrechtsen, Anders; Skotte, Line; Lindgreen, Stinus; Metspalu, Mait; Jombart, Thibaut; Kivisild, Toomas; Zhai, Weiwei; Eriksson, Anders; Manica, Andrea; Orlando, Ludovic; Vega, Francisco M. De La; Tridico, Silvana; Metspalu, Ene; Nielsen, Kasper; Ávila-Arcos, María C.; Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Muller, Craig; Dortch, Joe; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Lund, Ole; Wesolowska, Agata; Karmin, Monika; Weinert, Lucy A.; Wang, Bo; Li, Jun; Tai, Shuaishuai; Xiao, Fei; Hanihara, Tsunehiko; Driem, George van; Jha, Aashish R.; Ricaut, François-Xavier; Knijff, Peter de; Migliano, Andrea B.; Romero, Irene Gallego; Kristiansen, Karsten; Lambert, David M.; Brunak, Søren; Forster, Peter; Brinkmann, Bernd; Nehlich, Olaf; Bunce, Michael; Richards, Michael; Gupta, Ramneek; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Krogh, Anders; Foley, Robert A.; Lahr, Marta M.; Balloux, Francois; Sicheritz-Pontén, Thomas; Villems, Richard; Nielsen, Rasmus; Wang, Jun; Willerslev, Eske (7 October 2011). "An Aboriginal Australian Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia". Science. 334 (6052): 94–98. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...94R. doi:10.1126/science.1211177. PMC 3991479. PMID 21940856.

- "Sequencing Uncovers a 9,000 Mile Walkabout" (PDF). illumina.com.

A lock of hair and the HiSeq® 2000 system identify a human migration wave that took more than 3,000 generations and 10,000 years to complete.

- "Aboriginal Australians descend from the first humans to leave Africa, DNA sequence reveals", Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

- "About Australia:Our Country". Australian Government.

Australia's first inhabitants, the Aboriginal people, are believed to have migrated from some unknown point in Asia to Australia between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

- Jared Diamond. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel. Random House. London. pp. 314–316

- Mulvaney, J. and Kamminga, J., (1999), Prehistory of Australia. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

- Lourandos, H., Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory (Cambridge University Press, 1997) p. 81

- "When did Australia's earliest inhabitants arrive?", University of Wollongong, 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- Barbetti M, Allen H (1972). "Prehistoric man at Lake Mungo, Australia, by 32,000 years BP". Nature. 240 (5375): 46–48. Bibcode:1972Natur.240...46B. doi:10.1038/240046a0. PMID 4570638.

- Dunn, Michael; Terrill, Angela; Reesink, Ger; Foley, Robert A.; Levinson, Stephen C. (23 September 2005). "Structural phylogenetics and the reconstruction of ancient language history". Science. 309 (5743): 2072–2075. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2072D. doi:10.1126/science.1114615. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-1B84-E. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 16179483.

- Spriggs, Matthew (1997). The Island Melanesians. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-16727-3.

- PV Kirch. 1997. The Lapita Peoples. Cambridge: Blackwell Publisher

- "Background Note: Micronesia". United States Department of State. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- Morgan, William N. (1988). Prehistoric Architecture in Micronesia. University of Texas Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-292-78621-9.

- The History of Mankind Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine by Professor Friedrich Ratzel, Book II, Section A, The Races of Oceania p. 165, picture of a stick chart from the Marshall Islands. MacMillan and Co., published 1896.

- Hage, P.; Marck, J. (2003). "Matrilineality and Melanesian Origin of Polynesian Y Chromosomes". Current Anthropology. 44 (S5): S121. doi:10.1086/379272.

- Kayser, M.; Brauer, S.; Cordaux, R.; Casto, A.; Lao, O.; Zhivotovsky, L.A.; Moyse-Faurie, C.; Rutledge, R.B.; et al. (2006). "Melanesian and Asian origins of Polynesians: mtDNA and Y chromosome gradients across the Pacific". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (11): 2234–2244. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl093. PMID 16923821.

- Su, B.; Underhill, P.; Martinson, J.; Saha, N.; McGarvey, S.T.; Shriver, M.D.; Chu, J.; Oefner, P.; Chakraborty, R.; Chakraborty, R.; Deka, R. (2000). "Polynesian origins: Insights from the Y chromosome". PNAS. 97 (15): 8225–8228. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.8225S. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.15.8225. PMC 26928. PMID 10899994.

- Kirch, P.V. (2000). On the road of the wings: an archaeological history of the Pacific Islands before European contact. London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23461-1. Quoted in Kayser, M.; et al. (2006).

- Green, Roger C.; Leach, Helen M. (1989). "New Information for the Ferry Berth Site, Mulifanua, Western Samoa". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 98 (3). Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Burley, David V.; Barton, Andrew; Dickinson, William R.; Connaughton, Sean P.; Taché, Karine (2010). "Nukuleka as a Founder Colony for West Polynesian Settlement: New Insights from Recent Excavations". Journal of Pacific Archaeology. 1 (2): 128–144.

- Resemblance of the name to an early Mangarevan founder god Atu Motua ("Father Lord") has made some historians suspect that Hotu Matua was added to Easter Island mythology only in the 1860s, along with adopting the Mangarevan language. The "real" founder would have been Tu'u ko Iho, who became just a supporting character in Hotu Matu'a centric legends. See Steven Fischer (1994). Rapanui's Tu'u ko Iho Versus Mangareva's 'Atu Motua. Evidence for Multiple Reanalysis and Replacement in Rapanui Settlement Traditions, Easter Island. The Journal of Pacific History, 29(1), 3–18. See also Rapa Nui / Geography, History and Religion. Peter H. Buck, Vikings of the Pacific, University of Chicago Press, 1938. pp. 228–236. Online version.

- Summary of Thomas S. Barthel's version of Hotu Matu'a's arrival to Easter Island.

- Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Penguin Books: 2005. ISBN 0-14-303655-6. Chapter 2: Twilight at Easter pp. 79–119. p. 89.

- Hunt, T.L., Lipo, C.P., 2006. Science, 1121879. See also "Late Colonization of Easter Island" in Science Magazine. Entire article Archived 29 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine is also hosted by the Department of Anthropology of the University of Hawaii.

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 305–307. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- J.P. Sigmond and L.H. Zuiderbaan (1979) Dutch Discoveries of Australia.Rigby Ltd, Australia. pp. 19–30 ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- Primary Australian History: Book F [B6] Ages 10–11. R.I.C. Publications. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-74126-688-7.

- "European discovery of New Zealand". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- "Cook's Journal: Daily Entries, 22 April 1770". Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Once were warriors – smh.com.au". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 November 2002. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Simati Faaniu (1983). "Chapter 17, Colonial Rule". In Hugh Laracy (ed.). Tuvalu : a history. Institute of Pacific Studies and Extension Services, University of the South Pacific. pp. 127–139. OCLC 20637433.

- Macdonald, Barrie (2001) Cinderellas of the Empire: towards a history of Kiribati and Tuvalu, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji, ISBN 982-02-0335-X, p. 1

- Ganse, Alexander. "History of French Polynesia, 1797 to 1889". Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- "Rapport annuel 2010" (PDF). IEOM Nouvelle-Calédonie. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Gray, J.A.C. Amerika Samoa, A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. 1960.

- Jose, Arthur Wilberforce (1941) [1928]. "Chapter V – Affairs in the Western Pacific" (PDF). In Bean, Charles Edwin Woodrow (ed.). Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Official Histories, Australian War Memorial. Volume IX – The Royal Australian Navy: 1914–1918 (9th ed.). Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014.

- Prange, Gordon W., Goldstein, Donald, & Dillon, Katherine. The Pearl Harbor Papers (Brassey's, 2000), pp. 17ff; Google Books entry on Prange et al.

- Fukudome, Shigeru, "Hawaii Operation". United States Naval Institute, Proceedings, 81 (December 1955), pp. 1315–1331

- For the Japanese designator of Oahu. Wilford, Timothy. "Decoding Pearl Harbor", in The Northern Mariner, XII, #1 (January 2002), p. 32 fn 81.

- Braithwaite, John; Charlesworth, Hilary; Reddy, Peter & Dunn, Leah (2010). "Chapter 7: The cost of the conflict". Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequencing peace in Bougainville. ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-921666-68-1.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (26 September 1997). "Shoichi Yokoi, 82, Is Dead; Japan Soldier Hid 27 Years". The New York Times.

- Dumont D'Urville, Jules-Sébastien-César (2003). Translated by Ollivier, Isabel; Biran, Antoine de; Clark, Geoffrey. "On the Islands of the Great Ocean". Journal of Pacific History. 38 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1080/0022334032000120512. JSTOR 25169637.

- Douglas & Ballard (2008) Foreign bodies: Oceania and the science of race 1750–1940

- Gillespie, Rosemary G.; Clague, David A. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islands. University of California Press. p. 706. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1.

- Ben Finney, The Other One-Third of the Globe, Journal of World History, Vol. 5, No. 2, Fall, 1994.

- "Coral island", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- "Nauru", Charting the Pacific. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- Academic American encyclopedia. Grolier Incorporated. 1997. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7172-2068-7.

- Lal, Brij Vilash; Fortune, Kate (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1.

- West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 521. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- Dunford, Betty; Ridgell, Reilly (1996). Pacific Neighbors: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. Bess Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-57306-022-6.

- Douglas, Bronwen (2014). Science, Voyages, and Encounters in Oceania, 1511–1850. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6.

- de Brosses, Charles (1756). Histoire des navigations aux terres Australes. Contenant ce que l'on sçait des moeurs & des productions des contrées découvertes jusqu'à ce jour; & où il est traité de l'utilité d'y faire de plus amples découvertes, & des moyens d'y former un établissement [History of voyages to the Southern Lands. Containing what is known concerning the customes and products of the countries so far discovered; and treating of the usefulness of making broader discoveries there, and of the means of setting up an establishment there] (in French). Paris: Durand.

- "SFT and the Earth's Tectonic Plates". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Frisch, Wolfgang; Meschede, Martin; Blakey, Ronald C. (2010), Plate Tectonics: Continental Drift and Mountain Building, Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 11–12, ISBN 978-3-540-76504-2.

- "Age of the Ocean Floor".

- Pain, C.F., Villans, B.J., Roach, I.C., Worrall, L. & Wilford, J.R. (2012): Old, flat and red – Australia's distinctive landscape. In: Shaping a Nation: A Geology of Australia. Blewitt, R.S. (Ed.) Geoscience Australia and ANU E Press, Canberra. pp. 227–275 ISBN 978-1-922103-43-7

- Kevin Mccue (26 February 2010). "Land of earthquakes and volcanoes?". Australian Geographic. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- New Zealand within Gondwana from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- "Fiji". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Clague, D.A. and Dalrymple, G.B. (1989) Tectonics, geochronology, and origin of the Hawaiian-Emperor Chain in Winterer, E.L. et al. (editors) (1989) The Eastern Pacific Ocean and Hawaii, Boulder, Geological Society of America.

- "Mauna Kea Volcano, Hawaii". Hvo.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- "Parks and Reserves – Australia's National Landscapes". Environment.gov.au. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Loffler, Ernst; Anneliese Loffler; A.J. Rose; Denis Warner (1983). Australia: Portrait of a continent. Richmond, Victoria: Hutchinson Group (Australia). pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-09-130460-7.

- Seabrooka, Leonie; McAlpinea, Clive; Fenshamb, Rod (2006). "Cattle, crops and clearing: Regional drivers of landscape change in the Brigalow Belt, Queensland, Australia, 1840–2004". Landscape and Urban Planning. 78 (4): 375–376. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.11.007.

- "Einasleigh upland savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Mitchell grass downs". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Eastern Australia mulga shrublands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Southeast Australia temperate savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Arnhem Land tropical savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Newman, Arnold (2002). Tropical Rainforest: Our Most Valuable and Endangered Habitat With a Blueprint for Its Survival Into the Third Millennium (2 ed.). Checkmark. ISBN 978-0816039739.

- McKenzie, D.W. (1987). Heinemann New Zealand atlas. Heinemann Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7900-0187-6.

- NZPCN (2006). New Zealand indigenous vascular plant checklist. ISBN 0-473-11306-6. Written by Peter de Lange, John W.D. Sawyer and J.R. Rolfe.

- "Hawaiian Native Plant Propagation Database". Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Stephen Buchmann; Gary Paul Nabhan (22 June 2012). The Forgotten Pollinators. ISBN 9781597269087. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Petroica pusilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- Higgins, P.J, ed. (1999). Handbook of Australian Birds (PDF). Melbourne: OUP. p. 1178.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Pycnonotus cafer". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22712695A94343459. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22712695A94343459.en.

- Pratt, H. Douglas; et al. (1987). The Birds of Hawaii and the Tropical Pacific. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02399-1.

- "Brown Goshawk | Birds in Backyards". www.birdsinbackyards.net. Birdlife Australia. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Turner, Angela K; Rose, Chris (1989). Swallows & Martins: An Identification Guide and Handbook. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-51174-9.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Myzomela cardinalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Howard Youth. "Hawaii's Forest Birds Sing the Blues". Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- Invasive Species: Animals – Brown Tree Snake, National Agricultural Library, United States Department of Agriculture, Retrieved 2010-08-31

- Christidis, L., Boles, W., 2008. Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian birds, Collingwood, Victoria, Australia. CSIRO Publishing.

- Steadman. 2006. Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2016). "Rollers, ground rollers & kingfishers". World Bird List Version 6.3. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 10 October 2016.