Midway Atoll

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; Hawaiian: Pihemanu Kauihelani) is a 2.4-square-mile (6.2 km2) atoll in the North Pacific Ocean at 28°12′N 177°21′W. Midway Atoll is an unorganized, unincorporated territory of the United States.

Unincorporated U.S. Territory Midway Islands | |

|---|---|

Island | |

Flag | |

| Anthem: "The Star-Spangled Banner" | |

Satellite image of Midway Atoll | |

Unincorporated U.S. Territory The Midway Atoll on the map  Unincorporated U.S. Territory Unincorporated U.S. Territory (Pacific Ocean) | |

| Coordinates: 28°12′N 177°21′W | |

| Country | |

| Country subdivision | United States Minor Outlying Islands |

| Claimed by U.S | August 28, 1867 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.6 sq mi (66.3 km2) |

| • Land | 2.4 sq mi (6.2 km2) |

| • Lagoon | 23.2 sq mi (60.1 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 0 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 40 |

| • Density | 0.0/sq mi (0.0/km2) |

| Time zone | Samoa Time (UTC−11:00) |

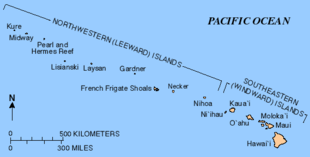

Roughly equidistant between North America and Asia, Midway is the only island in the Hawaiian archipelago that is not part of the state of Hawaii.[1] Unlike the other Hawaiian islands, Midway observes Samoa Time (UTC−11:00, i.e., eleven hours behind Coordinated Universal Time), which is one hour behind the time in the state of Hawaii. For statistical purposes, Midway is grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands. The Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, encompassing 590,991.50 acres (239,165.77 ha)[2] of land and water in the surrounding area, is administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). The refuge and most of its surrounding area are part of the larger Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

From 1941 until 1993, the atoll was the home of the Naval Air Facility Midway Island, which played a crucial role in The Battle of Midway, fought from June 4 until June 6, 1942. Aircraft based at the then-named Henderson Field on Eastern Island joined with United States Navy ships and planes in an attack on a Japanese battle group that sunk four carriers, one heavy cruiser and defended the atoll from invasion. The battle was a critical Allied victory and major turning point of the Pacific campaign of World War II.

Approximately 100 to 200 people live on the atoll, which includes staff of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and contract workers. Visitation to the atoll is possible only for business reasons (which includes permanent and temporary staff, contractors and volunteers) as the tourism program has been suspended due to budget cutbacks. In 2012, the last year that the visitor program was in operation, 332 people made the trip to Midway.[3][4][5][6][7] Tours focused on both the unique ecology of Midway as well as its military history. The economy is derived solely from governmental sources and tourist fees. Nearly all supplies must be brought to the island by ship or plane, though a hydroponic greenhouse and garden supply some fresh fruits and vegetables.

Location

As its name suggests, Midway is roughly equidistant between North America and Asia, and lies almost halfway around the world longitudinally from Greenwich, UK. It is near the northwestern end of the Hawaiian archipelago, about one-third of the way from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Tokyo, Japan. Midway island is not considered part of the State of Hawaii due to the passage of the Hawaii Organic Act, which formally annexed Hawaii to the United States as a territory, only defined Hawaii as "the islands acquired by the United States of America under an Act of Congress entitled 'Joint resolution to provide for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States,' approved July seventh, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight." Although it could be argued that Midway became part of Hawaii when Middlebrooks discovered it in 1859, it was assumed at the time that Midway was independently acquired by the U.S. when Reynolds visited in 1867, and so was not considered part of the Territory.

In defining which islands the State of Hawaii would inherit from the Territory, the Hawaii Admission Act clarified the question, specifically excluding Midway (along with Palmyra Island, Johnston Island, and Kingman Reef) from the jurisdiction of the state.[8]

Midway Atoll is approximately 140 nautical miles (259 km; 161 mi) east of the International Date Line, about 2,800 nautical miles (5,200 km; 3,200 mi) west of San Francisco, and 2,200 nautical miles (4,100 km; 2,500 mi) east of Tokyo.

Geography and geology

| Island | acres | hectares |

|---|---|---|

| Sand Island | 1,117 | 452 |

| Eastern Island | 336 | 136 |

| Spit Island | 15 | 6 |

| Total land | 1,549 | 627 |

| Submerged reef/ocean | 580,392 | 234,876 |

Midway Atoll is part of a chain of volcanic islands, atolls, and seamounts extending from Hawaii up to the tip of the Aleutian Islands and known as the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain. It consists of a ring-shaped barrier reef nearly five miles in diameter[10] and several sand islets. The two significant pieces of land, Sand Island and Eastern Island, provide a habitat for millions of seabirds. The island sizes are shown in the table above. The atoll, which has a small population (approximately 60 in 2014,[11] but no indigenous inhabitants), is designated an insular area under the authority of the United States Department of the Interior.

Midway was formed roughly 28 million years ago when the seabed underneath it was over the same hotspot from which the Island of Hawaii is now being formed. In fact, Midway was once a shield volcano, perhaps as large as the island of Lana'i. As the volcano piled up lava flows building the island, its weight depressed the crust and the island slowly subsided over a period of millions of years, a process known as isostatic adjustment.

As the island subsided, a coral reef around the former volcanic island was able to maintain itself near sea level by growing upwards. That reef is now over 516 feet (157 m) thick[12] (in the lagoon, 1,261 feet (384 m), comprised mostly post-Miocene limestones with a layer of upper Miocene (Tertiary g) sediments and lower Miocene (Tertiary e) limestones at the bottom overlying the basalts). What remains today is a shallow water atoll about 6 miles (9.7 km) across. Following Kure Atoll, Midway is the 2nd most northerly atoll in the world.

Infrastructure

The atoll has some 20 miles (32 km) of roads, 4.8 miles (7.7 km) of pipelines, one port on Sand Island (World Port Index Nr. 56328, MIDWAY ISLAND), and an airfield. As of 2004, Henderson Field airfield at Midway Atoll, with its one active runway (rwy 06/24, around 8,000 feet (2,400 m) long) has been designated as an emergency diversion airport for aircraft flying under ETOPS rules. Although the FWS closed all airport operations on November 22, 2004, public access to the island was restored from March 2008.[13]

Eastern Island Airstrip is a disused airfield which was in use by U.S. forces during the Battle of Midway. It is mostly constructed of Marston Mat and was built by the United States Navy Seabees.

Climate

Despite being located at 28°12'N which is north of the Tropic of Cancer, Midway Atoll has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw)[14] with very pleasant year-round temperatures. Rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year, with only two months being able to be classified as dry season months (May and June).

| Climate data for Midway Atoll | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

78 (26) |

79 (26) |

82 (28) |

86 (30) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

89 (32) |

88 (31) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 70.0 (21.1) |

69.4 (20.8) |

70.2 (21.2) |

71.7 (22.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

80.7 (27.1) |

82.5 (28.1) |

83.5 (28.6) |

83.5 (28.6) |

80.0 (26.7) |

75.8 (24.3) |

72.1 (22.3) |

76.2 (24.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 62.2 (16.8) |

61.7 (16.5) |

62.6 (17.0) |

64.1 (17.8) |

67.4 (19.7) |

72.8 (22.7) |

74.6 (23.7) |

75.6 (24.2) |

75.1 (23.9) |

72.4 (22.4) |

68.4 (20.2) |

64.4 (18.0) |

68.4 (20.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 51 (11) |

51 (11) |

51 (11) |

53 (12) |

55 (13) |

62 (17) |

63 (17) |

64 (18) |

64 (18) |

60 (16) |

55 (13) |

51 (11) |

51 (11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.85 (123) |

3.82 (97) |

3.05 (77) |

2.98 (76) |

2.42 (61) |

2.06 (52) |

3.44 (87) |

4.32 (110) |

3.84 (98) |

3.79 (96) |

3.83 (97) |

4.09 (104) |

42.52 (1,080) |

| Average precipitation days | 16 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 160 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[15] | |||||||||||||

History

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 21 | — | |

| 1910 | 35 | 66.7% | |

| 1920 | 31 | −11.4% | |

| 1930 | 36 | 16.1% | |

| 1940 | 437 | 1,113.9% | |

| 1950 | 416 | −4.8% | |

| 1960 | 2,356 | 466.3% | |

| 1970 | 2,220 | −5.8% | |

| 1980 | 453 | −79.6% | |

| 1990 | 13 | −97.1% | |

| 2000 | 4 | −69.2% | |

| 2010 | 0 | −100.0% | |

| Est. 2014 | 40 | [16] | |

Midway has no indigenous inhabitants and was uninhabited until the 19th century.

19th century

The atoll was sighted on July 5, 1859, by Captain N.C. Middlebrooks, commonly known as Captain Brooks, of the sealing ship Gambia. The islands were named the "Middlebrook Islands" or the "Brook Islands". Brooks claimed Midway for the United States under the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which authorized Americans to occupy uninhabited islands temporarily to obtain guano. There is no record of any attempt to mine guano on the island. On August 28, 1867, Captain William Reynolds of USS Lackawanna formally took possession of the atoll for the United States;[17] the name changed to "Midway" some time after this. The atoll was the first Pacific island annexed by the United States, as the Unincorporated Territory of Midway Island, and was administered by the United States Navy.

_in_May_2008_with_cocos_nucifera.jpg)

The first attempt at settlement was in 1871, when the Pacific Mail Steamship Company started a project of blasting and dredging a ship channel through the reef to the lagoon using money put up by the United States Congress. The purpose was to establish a mid-ocean coaling station to avoid the high taxes imposed at ports controlled by the Kingdom of Hawaii. The project was shortly a complete failure, and USS Saginaw evacuated the last of the channel project's work force in October 1871. The ship ran aground at Kure Atoll, stranding everyone. All were rescued, with the exception of four of the five persons who sailed to Kauai in an open boat to seek help.

Early 20th century

.jpg)

In 1903, workers for the Commercial Pacific Cable Company took up residence on the island as part of the effort to lay a trans-Pacific telegraph cable. These workers introduced many non-native species to the island, including the canary, cycad, Norfolk Island pine, she-oak, coconut, and various deciduous trees; along with ants, cockroaches, termites, centipedes, and countless others.

On January 20, 1903, the United States Navy opened a radio station in response to complaints from cable company workers about Japanese squatters and poachers. Between 1904 and 1908, President Roosevelt stationed 21 Marines on the island to end wanton destruction of bird life and keep Midway safe as a U.S. possession, protecting the cable station.

In 1935, operations began for the Martin M-130 flying boats operated by Pan American Airlines. The M-130s island-hopped from San Francisco to China, providing the fastest and most luxurious route to the Far East and bringing tourists to Midway until 1941. Only the very wealthy could afford the trip, which in the 1930s cost more than three times the annual salary of an average American. With Midway on the route between Honolulu and Wake Island, the flying boats landed in the atoll and pulled up to a float offshore in the lagoon. Tourists transferred to the Pan Am Hotel or the "Gooneyville Lodge", named after the ubiquitous "Gooney birds" (albatrosses).

.jpg) Burning oil tanks during the Battle of Midway | |

| Location | Sand Island, Midway Islands, United States Minor Outlying Islands |

|---|---|

| Built | 1941 |

| Architect | United States Navy |

| NRHP reference No. | 87001302 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 28, 1987[18] [19] |

| Designated NHLD | May 28, 1987[20] |

World War II

The location of Midway in the Pacific became important militarily. Midway was a convenient refueling stop on transpacific flights, and was also an important stop for Navy ships. Beginning in 1940, as tensions with the Japanese rose, Midway was deemed second only to Pearl Harbor in importance to the protection of the U.S. west coast. Airstrips, gun emplacements and a seaplane base quickly materialized on the tiny atoll.[21]

The channel was widened, and Naval Air Station Midway was completed. Midway was also an important submarine base.[21]

On February 14, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8682 to create naval defense areas in the central Pacific territories. The proclamation established "Midway Island Naval Defensive Sea Area", which encompassed the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding Midway. "Midway Island Naval Airspace Reservation" was also established to restrict access to the airspace over the naval defense sea area. Only U.S. government ships and aircraft were permitted to enter the naval defense areas at Midway Atoll unless authorized by the Secretary of the Navy.

Midway's importance to the U.S. was brought into focus on December 7, 1941 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Midway was attacked by two destroyers on the same day,[21] and the Japanese force was successfully repulsed in the first American victory of the war. A Japanese submarine bombarded Midway on February 10, 1942.[22]

Four months later, on June 4, 1942, a major naval battle near Midway resulted in the U.S. Navy inflicting a devastating defeat on the Japanese Navy. Four Japanese fleet aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū and Sōryū, were sunk, along with the loss of hundreds of Japanese aircraft, losses that the Japanese would never be able to replace. The U.S. lost the aircraft carrier Yorktown, along with a number of its carrier- and land-based aircraft that were either shot down by Japanese forces or bombed on the ground at the airfields. The Battle of Midway was, by most accounts, the beginning of the end of the Japanese Navy's control of the Pacific Ocean.

Starting in July 1942, a submarine tender was always stationed at the atoll to support submarines patrolling Japanese waters. In 1944, a floating dry dock joined the tender.[23] After the Battle of Midway, a second airfield was developed, this one on Sand Island. This work necessitated enlarging the size of the island through land fill techniques, that when concluded, more than doubled the size of the island.

Korean and Vietnam Wars

From August 1, 1941 to 1945, it was occupied by U.S. military forces. In 1950, the Navy decommissioned Naval Air Station Midway, only to re-commission it again to support the Korean War. Thousands of troops on ships and aircraft stopped at Midway for refueling and emergency repairs. From 1968 to September 10, 1993, Midway Island was a Naval Air Facility.

During the Cold War the U.S. established a shore terminal of the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), Naval Facility (NAVFAC) Midway Island, to track Soviet submarines. The facility became operational in 1968 and was commissioned 13 January 1969. It remained secret until its decommissioning on 30 September 1983 after data from its arrays had been remoted first to Naval Facility Barbers Point, Hawaii in 1981 and then directly to the Naval Ocean Processing Facility (NOPF) Ford Island, Hawaii.[24][25] U.S. Navy WV-2 (EC-121K) "Willy Victor" radar aircraft flew night and day as an extension of the Distant Early Warning Line, and antenna fields covered the islands.

With about 3,500 people living on Sand Island, Midway also supported the U.S. troops during the Vietnam War. In June 1969, President Richard Nixon held a secret meeting with South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu at the Officer-in-Charge house or "Midway House".

Civilian handover

In 1978, the Navy downgraded Midway from a Naval Air Station to a Naval Air Facility and large numbers of personnel and dependents began leaving the island. With the war in Vietnam over, and with the introduction of reconnaissance satellites and nuclear submarines, Midway's significance to U.S. national security was diminished. The World War II facilities at Sand and Eastern Islands were listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 28, 1987 and were simultaneously added as a National Historic Landmark.[20]

As part of the Base Realignment and Closure process, the Navy facility on Midway has been operationally closed since September 10, 1993, although the Navy assumed responsibility for cleaning up environmental contamination.

2011 tsunami

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami on March 11 caused many deaths among the bird population on Midway.[26] It was reported that a 1.5 m (5 ft) high wave completely submerged the atoll's reef inlets and Spit Island, killing more than 110,000 nesting seabirds at the National Wildlife Refuge.[27] However, scientists on the island do not think it will have long-term negative impacts on the bird populations.[28]

A U.S. Geological Survey study found that the Midway Atoll, Laysan, and Pacific islands like them could become inundated and unfit to live on during the 21st century, due to increased storm waves and rising sea levels.[29][30]

National Wildlife Refuge

| Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial | |

|---|---|

IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area) | |

Navy memorial and gooney monument with Laysan albatross chicks | |

| Location | Midway Atoll |

| Area | 2,365.3 km2 (913.2 sq mi)[31] |

| Established | 1988 |

| Governing body | United States Fish & Wildlife Service |

| Website | Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial |

Midway was designated an overlay National Wildlife Refuge on April 22, 1988 while still under the primary jurisdiction of the Navy.

From August 1996, the general public could visit the atoll through study ecotours.[32] This program ended in 2002,[33] but another visitor program was approved and began operating in March 2008.[13][34] This program operated through 2012, but was suspended for 2013 due to budget cuts.[5]

On October 31, 1996, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 13022, which transferred the jurisdiction and control of the atoll to the United States Department of the Interior. The FWS assumed management of the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. The last contingent of Navy personnel left Midway on June 30, 1997 after an ambitious environmental cleanup program was completed.

On September 13, 2000, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt designated the Wildlife Refuge as the Battle of Midway National Memorial.[35] The refuge is now titled as the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial.

On June 15, 2006, President George W. Bush designated the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands as a national monument. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument encompasses 105,564 square nautical miles (139,798 sq mi; 362,074 km2), and includes 3,910 square nautical miles (5,178 sq mi; 13,411 km2) of coral reef habitat.[36] The Monument also includes the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge and the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.

In 2007, the Monument's name was changed to Papahānaumokuākea (Hawaiian pronunciation: [ˈpɐpəˈhaːnɔuˈmokuˈaːkeə]) Marine National Monument.[37][38][39] The National Monument is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the State of Hawaii. In 2016 President Obama expanded the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, and added the Office of Hawaiian Affairs as a fourth co-trustee of the monument.

Environment

Midway Atoll is a critical habitat in the central Pacific Ocean which includes breeding habitat for 17 seabird species. A number of native species rely on the island, which is now home to 67–70% of the world's Laysan albatross population, and 34–39% of the global population of black-footed albatross.[40] A very small number of the very rare short-tailed albatross also have been observed. Fewer than 2,200 individuals of this species are believed to exist due to excessive feather hunting in the late nineteenth century.[41] In 2007–8, the US Fish and Wildlife Service translocated 42 endangered Laysan ducks to the atoll as part of their efforts to conserve the species.

Over 250 different species of marine life are found in the 300,000 acres (120,000 ha) of lagoon and surrounding waters. The critically endangered Hawaiian monk seals raise their pups on the beaches, relying on the atoll's reef fish, squid, octopus and crustaceans. Green sea turtles, another threatened species, occasionally nest on the island. The first was found in 2006 on Spit Island and another in 2007 on Sand Island. A resident pod of 300 spinner dolphins live in the lagoons and nearshore waters.[42]

The islands of Midway Atoll have been extensively altered as a result of human habitation. Starting in 1869 with the project to blast the reefs and create a port on Sand Island, the environment of Midway atoll has experienced profound changes.

A number of invasive exotics have been introduced; for example, ironwood trees from Australia were planted to act as windbreaks. Seventy-five percent of the 200 species of plants on Midway are non-native. Recent efforts have focused on removing non-native plant species and re-planting native species.

Lead paint on the buildings posed an environmental hazard (avian lead poisoning) to the albatross population of the island. In 2018, a project to strip the paint was completed.[43]

Pollution

Midway Atoll, in common with all the Hawaiian Islands, receives substantial amounts of marine debris from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Consisting of ninety percent plastic, this debris accumulates on the beaches of Midway. This garbage represents a hazard to the bird population of the island. Twenty tons of plastic debris washes up on Midway every year, with five tons of that debris being fed to Albatross chicks.[44] The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service estimates at least 100 pounds (45 kg) of plastic washes up every week.[45]

Of the 1.5 million Laysan Albatrosses that inhabit Midway, nearly all are found to have plastic in their digestive system.[46] Approximately one-third of the chicks die.[47] These deaths are attributed to the albatrosses confusing brightly colored plastic with marine animals (such as squid and fish) for food.[48] Recent results suggest that oceanic plastic develops a chemical signature that is normally used by seabirds to locate food items.[49]

Because albatross chicks do not develop the reflex to regurgitate until they are four months old, they cannot expel the plastic pieces. Albatrosses are not the only species to suffer from the plastic pollution; sea turtles and monk seals also consume the debris.[48] All kinds of plastic items wash upon the shores, from cigarette lighters to toothbrushes and toys. An albatross on Midway can have up to 50% of its intestinal tract filled with plastic.[45]

Transportation

The usual method of reaching Sand Island, Midway Atoll's only populated island, is on chartered aircraft landing at Sand Island's Henderson Field, which also functions as an emergency diversion point runway for transpacific flights.

References

- "MODIS Web: Home >> Images >> Midway Islands". modis.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- System, National Wildlife Refuge. "Lands Report – National Wildlife Refuge System". fws.gov. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- Visiting Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. FWS Website.

- Volunteer at Midway Atoll NWR. FWS Website.

- Ecotourism ends at Midway Atoll. Star-Advertiser, November 16, 2012

- . Galápagos Travel Website, November 16, 2012.

- . Photo Safaris Website, November 16, 2012.

- "GET /dgs HTTP/1.1 Host: www.WebComposition.net". 2009 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE: 1–10. 2009. doi:10.1109/hicss.2009.229. ISBN 9780769534503.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. "More About Midway". Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. "More About Midway". Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- "Hawaii: Midway Atoll – TripAdvisor". tripadvisor.com. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- Ladd, H. S.; Tracey, J. I., Jr. & Gross, M. G. (1967). "Drilling on Midway Atoll, Hawaii". Science. 156 (3778): 1088–1095. Bibcode:1967Sci...156.1088L. doi:10.1126/science.156.3778.1088. PMID 17774053. Also reprinted here .

- "Midway Atoll Program to Reopen in March" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. January 11, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008.

- "Midway Island Climate Midway Island Temperatures Midway Island Weather Averages". www.midway.climatemps.com. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "MIDWAY SAND ISLAND, PACIFIC OCEAN NCDC 1971-2000 Monthly Normals". wrcc.dri.edu. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- "Australia-Oceania :: MIDWAY ISLANDS". CIA World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- "GAO/OGC-98-5 – U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution". U.S. Government Printing Office. November 7, 1997. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- NHL designations

- "World War II Facilities at Midway". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- Preparing for War Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial.

- Polmar, Norman; Allen, Thomas B. (August 15, 2012). World War II: the Encyclopedia of the War Years, 1941–1945. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486479620. Retrieved September 16, 2016 – via Google Books.

- "After the Battle of Midway". Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. Fish & Wildlife Service. November 23, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- "Integrated Undersea Surveillance System (IUSS) History 1950 - 2010". IUSS/CAESAR Alumni Association. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- Commander Undersea Surveillance. "Naval Facility Midway Island January 1969 - September 1983". U.S. Navy. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Brandon Keim (March 15, 2011). "Midway's Albatrosses Survive the Tsunami". Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- "Tsunami washes away feathered victims west of Hawaii". CNN. March 19, 2011. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- Hiraishi, Tetsuya; Yoneyama, N.; Baba, Y.; Azuma, R. (July 10, 2013), "Field Survey of the Damage Caused by the 2011 Off the Pacific Coast of Tohoku Earthquake Tsunami", Natural Disaster Science and Mitigation Engineering: DPRI reports, Springer Japan, pp. 37–48, doi:10.1007/978-4-431-54418-0_4, ISBN 9784431544173

- "Storm Surges, Rising Seas Could Doom Pacific Islands This Century: Atolls and other low-lying islands in the Pacific Ocean may not slip under the waves but they will likely become uninhabitable due to overwashing waves" ClimateWire and Scientific American April 12, 2013

- Storlazzi, Curt D.; Berkowitz, Paul; Reynolds, Michelle H.; Logan, Joshua B. (2013). "Forecasting the Impact of Storm Waves and Sea-Level Rise on Midway Atoll and Laysan Island within the Papa hānaumokuākea Marine National Monument — A Comparison of Passive Versus Dynamic Inundation Models" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- "Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge". protectedplanet.net. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- "Study Tours of Midway Island". New York Times. July 7, 1996. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- Pandion Systems, Inc. (April 12, 2005). "Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge: Visitor program market analysis and feasibility study" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- "Interim Visitor Services Plan Approved". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. December 8, 2006. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- "Battle of Midway National Memorial". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. March 22, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument". noaa.gov. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Papahānaumokuākea: A Sacred Name, A Sacred Place". Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2008.;

Hawaiian pronunciation is given here.Archived March 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine - "Fact Sheet: President Obama to Create the World's Largest Marine Protected Area". whitehouse.gov. August 26, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Secretaries Pritzker, Jewell Applaud President's Expansion of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument". commerce.gov. August 26, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "Midway's albatross population stable – The Honolulu Advertiser – Hawaii's Newspaper". honoluluadvertiser.com. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- "U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — Birds of Midway Atoll". August 19, 2009. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- "U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — Marine Life of Midway Atoll". August 19, 2009. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- "Millions of Albatrosses Now Lead-free on Midway". American Bird Conservancy. August 17, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Plastic-Filled Albatrosses Are Pollution Canaries in New Doc Wired. June 29, 2012. Accessed 6-11-13

- "U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — Marine Debris: Cigarette Lighters and the Plastic Problem on Midway Atoll" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 21, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- Chris Jordan (November 11, 2009). "Midway: Message from the Gyre". Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- "Q&A: Your Midway questions answered". BBC News. March 28, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- McDonald, Mark. "The Fatal Shore Awash in Plastic". Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- Savoca, M. S.; Wohlfeil, M. E.; Ebeler, S. E.; Nevitt, G. A. (November 2016). "Marine plastic debris emits a keystone infochemical for olfactory foraging seabirds". Science Advances. 2 (11): e1600395. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E0395S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600395. PMC 5569953. PMID 28861463.

Further reading

Natural history

- Hubert, Mabel, Carl Frings, and H. Franklin – Sounds of Midway: Calls of Albatrosses of Midway.

- Mearns, Edgar Alexander – A List of the Birds Collected by Dr. Paul Bartsch in the Philippine Islands, Borneo, Guam, and Midway Island, with Descriptions of Three New Forms.

- Fisher, Mildred L. (1970). The Albatross of Midway Island: A Natural History of the Laysan Albatross. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-0426-4.

- Rauzon, Mark J (2001). Isles of Refuge: Wildlife and History of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2209-9.

Military history

- Fuchida, Mitsuo; Okumiya, Masatake; Kawakami, Clarke H.; Pineau, Roger (1955). Midway: The Battle That Doomed Japan. Naval Institute Press.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1950). Coral Sea, Midway, and Submarine Actions, May, 1942 – August, 1942. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Frank, Pat; Harrington, Joseph D.; Fletcher, Frank; Tanaube, Yahachi (1967). Rendezvous at Midway: U. S. S. Yorktown and the Japanese Carrier Fleet. New York: John Day Co.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Herndon, VA: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-57488-923-9.

- Prange, Gordon W.; Goldstein, Donald M.; Dillon, Katherine V. (1982). Miracle at Midway. New York: MJF Books. ISBN 1-56731-895-9.

- Smith, Myron J. (1991). The Battles of Coral Sea and Midway, 1942: A Selected Bibliography (annotated edition). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-28120-4.

- Toland, John (1974). But Not in Shame: The Six Months after Pearl Harbour. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25748-0.

- Tuleja, Thaddeus (1983). Climax at Midway. Jove. ISBN 0-515-07403-9.

- Wildenberg, Thomas (1998). Destined for Glory: Dive Bombing, Midway, and the Evolution of Carrier Airpower. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-947-6.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Midway Islands. |

- https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/hrscurrent/Vol01_Ch0001-0042F/04-ADM/ADM-.htm

- Satellite Map and NOAA Chart of Midway on BlooSee

- AirNav – Henderson Field Airport : Airport facilities and navigational aids.

- Diary from the middle of nowhere BBC's environment correspondent David Shukman reports on the threat of plastic rubbish drifting in the North Pacific Gyre to Midway. Accessed 2008-03-26.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial (this article incorporated some content from this public domain site)

- NOAA Midway Island Hawaiian Monk Seal Captive Care & Release Project

- The Battle of Midway: Turning the Tide in the Pacific, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Marines at Midway: by Lieutenant Colonel R.D. Heinl, Jr., USMC Historical Section, Division of Public Information Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps 1948,

- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Past residents of Midway Discussion of Midway related topics by former residents and those interested in Midway.

- Midway Atoll Today (2010)

- Google Street View Jun 2012

- Island Conservation: Midway Atoll Restoration Project