Newfoundland (island)

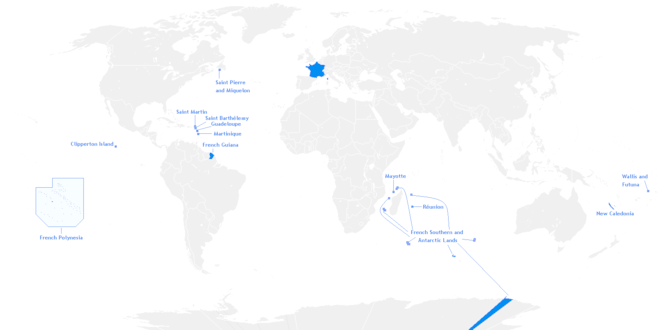

Newfoundland (/ˈnjuːfən(d)lənd, -lænd, njuːˈfaʊnd-/, locally /ˌnjuːfəndˈlænd/;[5] French: Terre-Neuve; Mi'kmaq: Taqamkuk)[6] is a large island off the east coast of the North American mainland, and the most populous part of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It has 29 percent of the province's land area. The island is separated from the Labrador Peninsula by the Strait of Belle Isle and from Cape Breton Island by the Cabot Strait. It blocks the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River, creating the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, the world's largest estuary. Newfoundland's nearest neighbour is the French overseas community of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon.

| Nickname: "The Rock"[1][2] | |

|---|---|

Satellite view of Newfoundland | |

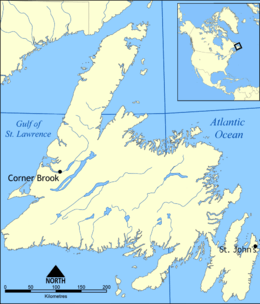

Map of Newfoundland | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 49°00′N 56°00′W |

| Area | 108,860 km2 (42,030 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 16th |

| Coastline | 9,656 km (6,000 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 814 m (2,671 ft) |

| Highest point | The Cabox |

| Administration | |

| Province | Newfoundland and Labrador |

| Largest settlement | St. John's (pop. 200,600) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Newfoundlander |

| Population | 479,538[3] (2016) |

| Population rank | 80 |

| Pop. density | 4.39/km2 (11.37/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | English, Irish, Scottish, French, and Mi'kmaq |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| • Summer (DST) |

|

| Longest river: Exploits River (246 kilometres (153 mi))[4] | |

With an area of 108,860 square kilometres (42,031 sq mi),[7] Newfoundland is the world's 16th-largest island, Canada's fourth-largest island, and the largest Canadian island outside the North. The provincial capital, St. John's, is located on the southeastern coast of the island; Cape Spear, just south of the capital, is the easternmost point of North America, excluding Greenland. It is common to consider all directly neighbouring islands such as New World, Twillingate, Fogo and Bell Island to be 'part of Newfoundland' (i.e., distinct from Labrador). By that classification, Newfoundland and its associated small islands have a total area of 111,390 square kilometres (43,008 sq mi).[8]

According to 2006 official Census Canada statistics, 57% of responding Newfoundland and Labradorians claim British or Irish ancestry, with 43.2% claiming at least one English parent, 21.5% at least one Irish parent, and 7% at least one parent of Scottish origin. Additionally 6.1% claimed at least one parent of French ancestry.[9] The island's total population as of the 2006 census was 479,105.

History

Long settled by indigenous peoples of the Dorset culture, the island was visited by the Icelandic explorer Leif Eriksson in the 11th century, who called the new land "Vinland".[10] The next European visitors to Newfoundland were Portuguese, Basque, Spanish, French, Dutch and English migratory fishermen and whalers. The island was visited by the Genoese navigator John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto), working under contract to King Henry VII of England on his expedition from Bristol in 1497. In 1501, Portuguese explorers Gaspar Corte-Real and his brother Miguel Corte-Real charted part of the coast of Newfoundland in a failed attempt to find the Northwest Passage. After European settlement, colonists first called the island Terra Nova, from "New Land" in Portuguese and Latin. The name Newfoundland in popular discourse came from people discussing the "New founde land" in the new world.

On August 5, 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed Newfoundland as England's first overseas colony under Royal Charter of Queen Elizabeth I of England, thus officially establishing a forerunner to the much later British Empire.[11] Newfoundland is considered Britain's oldest colony.[12] At the time of English settlement, the Beothuk inhabited the island.

L'Anse aux Meadows was a Norse settlement near the northernmost tip of Newfoundland (Cape Norman), which has been dated to be approximately 1,000 years old. The site is considered the only undisputed evidence of Pre-Columbian contact between the Old and New Worlds, if the Norse-Inuit contact on Greenland is not counted. Point Rosee, in southwest Newfoundland, was thought to be a second Norse site until excavations in 2015 and 2016 found no evidence of any Norse presence.[13] The island is a likely location of Vinland, mentioned in the Viking Chronicles, although this has been disputed.

The indigenous people on the island at the time of European settlement were the Beothuk, who spoke an Amerindian language of the same name. Later immigrants developed a variety of dialects associated with settlement on the island: Newfoundland English, Newfoundland French.[14] In the 19th century, it also had a dialect of Irish known as Newfoundland Irish.[14] Scottish Gaelic was spoken on the island during the 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the Codroy Valley area, chiefly by settlers from Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia.[15] The Gaelic names reflected the association with fishing: in Scottish Gaelic, it was called Eilean a' Trosg, or literally, "Island of the Cod".[16] Similarly, the Irish name Talamh an Éisc means "Land of the Fish".

First inhabitants

The first inhabitants of Newfoundland were the Paleo-Eskimo, who have no known link to other groups in Newfoundland history. Little is known about them beyond archeological evidence of early settlements. Evidence of successive cultures have been found. The Late Paleo-Eskimo, or Dorset culture, settled there about 4,000 years ago. They were descendants of migrations of ancient prehistoric peoples across the High Arctic thousands of years ago, after crossing from Siberia via the Bering land bridge. The Dorset died off or abandoned the island prior to the arrival of the Norse.[17]

After this period, the Beothuk settled Newfoundland, migrating from Labrador on the mainland. There is no evidence that the Beothuk inhabited the island prior to Norse settlement. Scholars believe that the Beothuk are related closely to the Innu of Labrador.[18] The tribe later was declared "extinct" although people of partial Beothuk descent have been documented.[19] The name Beothuk meant "people" in the Beothuk language which is often considered to be a member of the Algonquian language family although the lack of sufficient records means that it is not possible to confidently demonstrate such a connection.[20]

The tribe is now officially said to be extinct, but evidence of its culture is preserved in museum, historical and archaeological records. Shanawdithit, a woman who is often regarded as the last full-blood Beothuk, died in St. John's in 1829 of tuberculosis. However, Santu Toney, who was born around 1835 and died in 1910, was a woman of mixed Mi'kmaq and Beothuk descent which means that some Beothuk must have lived on beyond 1829. Her father was a Beothuk and mother a Mi'kmaq, both from Newfoundland. The Beothuk may have intermingled and assimilated with Innu in Labrador and Mi'kmaq in Newfoundland. Oral histories also suggest potential historical competition and hostility between the Beothuk and Mi'kmaq.[21] The Mi'kmaq, Innu and Inuit all hunted and fished around Newfoundland before the arrival of Europeans but no evidence indicates that they lived on the island for long periods of time and would only travel to Newfoundland temporarily. Inuit have been documented on the Great Northern Peninsula as late as the 18th-Century. Newfoundland was historically the southernmost part of the Inuit's territorial range.

When Europeans arrived from 1497 and later, starting with John Cabot, they established contact with the Beothuk. Estimates of the number of Beothuk on the island at this time vary, at an average of 700.[22]

Later both the English and French settled the island. They were followed by the Mi'kmaq, an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people from eastern Canada and present-day Nova Scotia. As European and Mi'kmaq settlement became year-round and expanded to new areas of the coast, the area available to the Beothuk to harvest the marine resources they relied upon was diminished. By the beginning of the 19th century, few Beothuk remained. Most died due to infectious diseases carried by Europeans, to which they had no immunity, and starvation. Government attempts to engage with the Beothuk and aid them came too late. The Beothuk were exceptionally hostile to foreigners, unlike the Mi'kmaq. The latter readily traded with Europeans and became established in settlements in Newfoundland.

European contact and settlement

Newfoundland is the site of the only authenticated Norse settlement in North America.[23] An archaeological site was discovered in 1960 at L'Anse aux Meadows by Norwegian explorer Helge Ingstad and his wife, archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad. This site was the subject of archaeological studies throughout the 1960s and 1970s. This research has revealed that the settlement dates to more than 500 years before the arrival of John Cabot in 1497; the site contains the earliest-known European structures in North America. Designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, it is believed to be the Vinland settlement of explorer Leif Erikson. (The Icelandic Skálholt map of 1570 refers to the area as "Promontorium Winlandiæ" and correctly shows it on a 51°N parallel with Bristol, England). Before and after the departure of the Norse, the island was inhabited by indigenous populations.[24]

Exploration by Cabot

About 500 years later, in 1497, the Italian navigator John Cabot (Zuan/Giovanni Caboto) became the first European since the Norse settlers to set foot on Newfoundland, working under commission of King Henry VII of England. His landing site is unknown but popularly believed to be Cape Bonavista, along the island's East coast.[25] Another site claimed is Cape Bauld, at the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula. A document found in the Spanish National Archives, written by a Bristol merchant, reports that Cabot's crew landed 1,800 miles or 2,900 kilometres west of Dursey Head, Ireland (latitude 51°35′N), which would put Cabot within sight of Cape Bauld. This document mentions an island that Cabot sailed past to go ashore on the mainland. This description fits with the Cape Bauld theory, as Belle Isle is not far offshore.[25]

Other European explorers

After Cabot, the first European visitors to Newfoundland were Portuguese, Basque, Spanish, French and English migratory fishermen. In 1501, Portuguese explorers Gaspar Corte-Real and his brother Miguel Corte-Real charted part of the coast of Newfoundland in a failed attempt to find the Northwest Passage. Late in the 17th century came Irish fishermen, who found so many fisheries that they named the island Talamh an Éisc, meaning "land of the [one] fish", or "the fishing grounds" in Irish. Newfoundland remains the only place outside of Europe to have a distinct Irish-language name.

Colonization

In 1583, when Sir Humphrey Gilbert formally claimed Newfoundland as a colony of England, he found numerous English, French and Portuguese vessels at St. John's. There was no permanent European population. Gilbert was lost at sea during his return voyage, and plans of settlement were postponed.

In July 1596 the Scottish vessel the "William" left Aberdeen for "new fund land" (Newfoundland) and returned in 1600.[26]

On July 5, 1610, John Guy set sail from Bristol, England with 39 other colonists for Cuper's Cove. This, and other early attempts at permanent settlement failed to make a profit for the English investors, but some settlers remained, forming the very earliest modern European population on the island. By 1620, the fishermen of England's West Country dominated the east coast of Newfoundland. French fishermen dominated the island's south coast and Northern Peninsula. The decline of the fisheries, the wasting of the shoreline forests, and an overstocking of liquor by local merchants influenced the Whitehall government in 1675 to decline to set up a colonial governor on the island.[27]

After 1713, with the Treaty of Utrecht, the French ceded control of south and north shores of the island to the British. They kept only the nearby islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, located in the fish-rich Grand Banks off the south coast. Despite some early settlements by the English, the Crown discouraged permanent, year-round, settlement of Newfoundland by migratory fishery workers. Thomas Nash was an Irish Catholic fisherman who permanently settled in Newfoundland. He established the fishing town of Branch.[28] He and his cousin Father Patrick Power of Callan, County Kilkenny, spread Catholicism in Newfoundland. This settlement attracted a major migration of Irish Catholic immigrants to Newfoundland in the early eighteenth century.[29]

By the late 18th century, permanent settlement increased, peaking in the early years of the 19th century.[30]

The French name for the island is Terre-Neuve. The name "Newfoundland"' is one of the oldest European place names in Canada in continuous geographical and cartographical use, dating from a 1502 letter. It was stated in the following 1628 poem:[31]

A Skeltonicall continued ryme, in praise of my New-found-Land

- Although in cloaths, company, buildings faire

- With England, New-found-land cannot compare:

- Did some know what contentment I found there,

- Alwayes enough, most times somewhat to spare,

- With little paines, lesse toyle, and lesser care,

- Exempt from taxings, ill newes, Lawing, feare,

- If cleane, and warme, no matter what you weare,

- Healthy, and wealthy, if men careful are,

- With much-much more, then I will now declare,

- (I say) if some wise men knew what this were

- (I doe beleeue) they'd live no other where.

- From 'The First Booke of Qvodlibets'

- Composed and done at Harbor-Grace in

- Britaniola, anciently called Newfound-Land

- by Governor Robert Hayman – 1628.

A new society

The European immigrants, mostly English, Scots, Irish and French, built a society in the New World unlike the ones they had left. It was also different from those that other immigrants would build on the North American mainland. As a fish-exporting society, Newfoundland was in contact with many ports and societies around the Atlantic rim. But its geographic location and political distinctiveness isolated it from its closest neighbours, Canada and the United States. Internally, most of its population was spread widely around a rugged coastline in small outport settlements. Many were distant from larger centres of population and isolated for long periods by winter ice or bad weather. These conditions had an effect on the cultures of the immigrants. They generated new ways of thinking and acting. Newfoundland and Labrador developed a wide variety of distinctive customs, beliefs, stories, songs and dialects.[32][33]

Effects of World Wars

The First World War had a powerful and lasting effect on the society. From a population of about a quarter of a million, 5,482 men went overseas. Nearly 1,500 were killed and 2,300 wounded. On July 1, 1916, at Beaumont-Hamel, France, 753 men of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment went over the top of a trench. The next morning, only 68 men answered the roll-call. Even now, when the rest of Canada celebrates the founding of the country on July 1, many Newfoundlanders take part in solemn ceremonies of remembrance.

The Second World War also had a lasting effect on Newfoundland. In particular, the United States assigned forces to the military bases at Argentia, Gander, Stephenville, Goose Bay and St. John's.

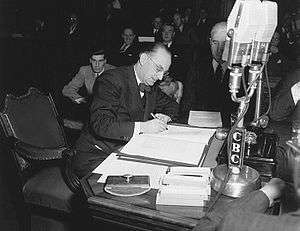

Newfoundland and Labrador is the youngest province in Canada. Newfoundland was organised as a colony in 1825, was self-governing from 1855–1934, and held dominion status from 1907–1949 (see Dominion of Newfoundland). In June 22 and July 3, 1948, the population of the colony voted 52.3% to 47.7%[34] in favour of joining Canada as a province. Opposition was concentrated among residents of the capital St. John's, and on the Avalon Peninsula.

Union with Canada

Newfoundland joined Canada on March 31, 1949. Union with Canada has done little to reduce Newfoundlanders' self-image as a unique group. In 2003, 72% of residents responding identified first as Newfoundlanders, secondarily as Canadians.[35] Separatist sentiment is low, though, less than 12% in the same 2003 study.

The referendum campaign of 1948 was bitterly fought, and interests in both Canada and Britain favoured and supported confederation with Canada. Jack Pickersgill, a western Canadian native and politician, worked with the confederation camp during the campaign. The Catholic Church, whose members were a minority on the island, lobbied for continued independence. Canada offered financial incentives, including a "baby bonus" for each child in a family. The Confederates were led by the charismatic Joseph Smallwood, a former radio broadcaster, who had developed socialist political inclinations while working for a socialist newspaper in New York City. His policies as premier were closer to liberalism than socialism.

Following confederation, Smallwood led Newfoundland for decades as the elected premier. He was said to have a "cult of personality" among his many supporters. Some residents featured photographs of "Joey" in their living rooms in a place of prominence.

Flags of Newfoundland

The first flag to specifically represent Newfoundland is thought to have been an image of a green fir tree on a pink background that was in use in the early 19th century.[36] The first official flag identifying Newfoundland, flown by vessels in service of the colonial government, was the Newfoundland Blue Ensign, adopted in 1870 and used until 1904, when it was modified slightly. In 1904, the crown of the Blue Ensign was replaced with the Great Seal of Newfoundland (having been given royal approval in 1827) and the British Parliament designated Newfoundland Red and Blue ensigns as official flags specifically for Newfoundland. The Red and Blue ensigns with the Great Seal of Newfoundland in the fly were used officially from 1904 until 1965, with the Red Ensign being flown as civil ensign by merchant shipping, and the Blue being flown by governmental ships (after the British tradition of having different flags for merchant/naval and government vessel identification).

On September 26, 1907, King Edward VII of the United Kingdom declared the Colony of Newfoundland, as an independent Dominion within the British Empire,[37] and from that point until 1965, the Newfoundland Red Ensign was used as the civil ensign of the Dominion of Newfoundland with the Blue Ensign, again, reserved for government shipping identification. In 1931 the Newfoundland National Assembly adopted the Union Jack as the official national flag, with the Red and Blue Ensigns retained as ensigns for shipping identification.[38]

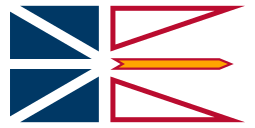

On March 31, 1949, Newfoundland became a province of Canada but retained the Union Jack in legislature, still designating it as the "national" flag. This was later reaffirmed by the Revised Statutes Act of 1952, and the Union Jack remained the official flag of Newfoundland until 1980, when it was replaced by the current provincial flag. (See Province of Newfoundland and Labrador for continued discussion of provincial flags.)

Points of interest and major settlements

Newfoundland has the most Dorset culture archeological sites. The Beothuk and Mi'kmaq did not leave as much evidence of their cultures.

As one of the first places in the New World where Europeans settled, Newfoundland also has a history of European colonization. St. John's is the oldest city in Canada and the oldest continuously settled location in English-speaking North America.

The St. John's census metropolitan area includes 12 suburban communities, the largest of which are the city of Mount Pearl and the towns of Conception Bay South and Paradise. The province's third-largest city is Corner Brook, which is situated on the Bay of Islands on the west coast of the island. The bay was named by Captain James Cook who surveyed the coast in 1767.[39]

The island of Newfoundland has numerous provincial parks such as Barachois Pond Provincial Park, considered to be a model forest, as well as two national parks.

- Gros Morne National Park is located on the west coast; it was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987 due to its complex geology and remarkable scenery. It is the largest national park in Atlantic Canada at 1,805 km2 (697 sq mi) and is a popular tourist destination.

- Terra Nova National Park, on the island's east side, preserves the rugged geography of the Bonavista Bay region. It allows visitors to explore the historic interplay of land, sea and man.

- L'Anse aux Meadows is an archaeological site located near the northernmost tip of the island (Cape Norman). It is the only known site of a Norse village in North America outside of Greenland, and is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site. It is the only widely accepted site of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. It has associations with the attempted colony of Vinland established by Leif Ericson around 1003.

The island has many tourism opportunities, ranging from sea kayaking, camping, fishing and hunting, to hiking. The International Appalachian Trail (IAT) is being extended along the island's mountainous west coast. On the east coast, the East Coast Trail extends through the Avalon Peninsula for 220 km (140 mi), beginning near Fort Amherst in St. John's and ending in Cappahayden, with an additional 320 km (200 mi) of trail under construction.

The Marble Mountain Ski Resort near Corner Brook is a major attraction in the winter for skiers in eastern Canada.

Other major communities include the following towns:

- Gander, home to the Gander International Airport.

- Grand Falls-Windsor, a service centre for the central part of the island.

- Channel-Port aux Basques, the "Gateway to Newfoundland", as it is the closest point on the island to the province of Nova Scotia, as well as the location of the Marine Atlantic ferry terminal connecting the island to the rest of Canada.

- Stephenville, former location of the Ernest Harmon Air Force Base and currently the Stephenville Airport.

Educational institutions include the provincial university, Memorial University of Newfoundland whose main campus is situated in St. John's, along with the Grenfell Campus in Corner Brook, in addition to the College of the North Atlantic based in Stephenville and other communities.

Bonavista, Placentia and Ferryland are all historic locations for various early European settlement or discovery activities. Tilting Harbour on Fogo Island is a provincial Registered Heritage District, as well as a National Cultural Landscape District of Canada. This is one of only two national historic sites in Canada so recognized for their Irish heritage.

Entertainment opportunities abound in the island's three cities and numerous towns, particularly during summer festivals. For nightlife, George Street, located in downtown St. John's, is closed to traffic 20 hours per day. The Mile One Stadium in St. John's is the venue for large sporting and concert events in the province.

In March, the annual seal hunt (of the harp seal) takes place.

Largest Municipalities (2011 population)

- St. John's (106,172)

- Conception Bay South (24,848)

- Mount Pearl (24,284)

- Corner Brook (20,886)

- Paradise (17,695)

- Grand Falls-Windsor (13,725)

- Gander (11,054)

- Torbay (7,397)

- Portugal Cove-St. Philip's (7,366)

- Stephenville (6,719)

- Clarenville (6,036)

- Marystown (5,506)

- Bay Roberts (5,818)

Geography

Newfoundland is roughly triangular, with each side being approximately 500 kilometres (310 mi), and having an area of 108,860 square kilometres (42,030 sq mi). Newfoundland and its associated small islands have a total area of 111,390 square kilometres (43,010 sq mi). Newfoundland extends between latitudes 46°36'N and 51°38'N.

Climate

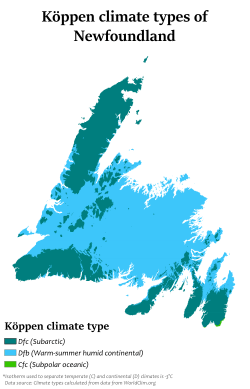

Newfoundland is primarily characterized by having a subarctic (Köppen Dfc) or a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb). Locations on the extreme southeast of the island receive sufficient maritime influence to qualify as having a subpolar oceanic climate (Köppen Cfc).

Geology

The Terreneuvian Epoch that begins the Cambrian Period of geological time is named for Terre Neuve (the French term for Newfoundland).[40]

Fauna and flora

Newfoundlanders

See also

- Baccalieu Island

- Flag of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Heritage Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Category:Newfoundland and Labrador

References

- Dekel, Jon (July 22, 2014). "Shaun Majumder brings Burlington, Newfoundland, to the world with Majumder Manor". National Post. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

After all, it’s not every day the a famous native son of The Rock returns to its capital.

- Gunn, Malcolm (July 10, 2014). "The term "go anywhere" has been redefined with the redesign of a family favorite". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

Canada's 10th province is called "The Rock" for good reason.

- "2016 Statistics Canada National Census". Statistics Canada. October 18, 2017.

- "Atlas of Canada – Rivers". Natural Resources Canada. October 26, 2004. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Both names can be found in this document Archived March 28, 2019, at the Wayback Machine."Ikkarumikluak" means "place of many shoals" while "Kallunasillik" means "place of many white people". It is thought the "Ikkarumiklua" was used before the colonization of Newfoundland and was later replaced by "Kallunasillik". It is also thought that "Ikkarumiklua" may have been a term for the Great Northern Peninsula and not the island as a whole.

- "Atlas of Canada, Islands". Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- "NL Government website: Areas". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved August 26, 2007.

- "2006 Statistics Canada National Census: Newfoundland and Labrador". Statistics Canada. July 28, 2009. Archived from the original on January 15, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- Editors, History com. "Leif Eriksson". HISTORY.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- GILBERT (Saunders Family), SIR HUMPHREY" (history), Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, University of Toronto, May 2, 2005

- "The British Empire: The Map Room". Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- Parcak, Sarah; Mumford, Gregory (November 8, 2017). "Point Rosee, Codroy Valley, NL (ClBu-07) 2016 Test Excavations under Archaeological Investigation Permit #16.26" (PDF). geraldpennyassociates.com, 42 pages. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

[The 2015 and 2016 excavations] found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period. […] None of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area [Point Rosee] as having any traces of human activity.

- "Language". www.heritage.nf.ca.

- Bennett, Margaret (1989). The Last Stronghold: Scottish Gaelic Traditions of Newfoundland, Canongate, 11 May 1989.

- Dwelly, Edward (1920). Illustrated Gaelic - English Dictionary, September 2001.

- "View of The Norse in Newfoundland: L'Anse aux Meadows and Vinland | Newfoundland and Labrador Studies". journals.lib.unb.ca.

- "Post-Contact Beothuk History". www.heritage.nf.ca.

- "View of Santu's Song | Newfoundland and Labrador Studies". journals.lib.unb.ca.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford University Press. p. 290. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- "The History of the Newfoundland Mi'kmaq". www.heritage.nf.ca.

- Heymans, Johanna J. (November 12, 2003). "Ecosystem models of Newfoundland and Southeastern Labrador : additional information and analyses for "back to the future"". doi:10.14288/1.0074790 – via open.library.ubc.ca. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "View of Cultural Heritage Tourism along the Viking Trail: An Analysis of Tourist Brochures for Attractions on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland | Newfoundland and Labrador Studies". journals.lib.unb.ca.

- Renouf, >M. A. P. (1999). "Prehistory of Newfoundlandhunter‐gatherers: Extinctions or adaptations?". World Archaeology. Informa UK Limited. 30 (3): 403–420. doi:10.1080/00438243.1999.9980420. ISSN 0043-8243.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kevin Major (August 2002). As Near to Heaven by Sea: A History of Newfoundland and Labrador. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-027864-8.

- "The Press and Journal:December 14, 2018" "First Scottish ship bound for America left Aberdeen more than 420 years ago

- "America and West Indies: May 1675." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 9, 1675-1676 and Addenda 1574-1674. Ed. W Noel Sainsbury. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1893. 222-238. British History Online Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Intangible Cultural Heritage | Branch. Mun.ca (2011-06-14). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- Jerry Bannister (2003). The Rule of the Admirals: Law, Custom and Naval Government in Newfoundland, 1699-1832. University of Toronto Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780802086136.

- Ninette Kelley; M. Trebilcock (2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. p. 40. ISBN 9781442690813.

- "Robert Hayman (1575-1629)". www.heritage.nf.ca.

- James Overton, "A Newfoundland Culture?." Journal of Canadian Studies 23.1-2 (1988): 5-22.

- James Baker, "As loved our fathers: The strength of patriotism among young Newfoundlanders." National Identities 14.4 (2012): 367-386.

- Baker, Melvin (1987). "The Tenth Province: Newfoundland joins Canada, 1949". Horizon. 10 (11): 2641–67. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- Ryan Research and Communications (April 2003). "Provincial Opinion Survey" (PDF). Government of Newfoundland and Labrador's Royal Commission on Renewing and Strengthening Our Place in Canada. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- "THE PROVINCES Chap XIX: Newfoundland". Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- "God Guard Thee, Newfoundland". September 2007. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- "Historic Flags of Newfoundland (Canada)". October 2005. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- Major, Kevin (2001). As Near To Heaven By Sea. Toronto: Penguin. pp. 127–129. ISBN 0-670-88290-9.

- Landing, E., Peng, S., Babcock, L. E., Geyer, G., & Moczydlowska-Vidal, M. (2007). Global standard names for the lowermost Cambrian series and stage. Episodes, 30(4), 287

Further reading

Modern histories

- Sean T. Cadigan. Newfoundland and Labrador: A History (2009) search and text excerpt

- John Gimlette, Theatre of Fish, (Hutchinson, London, 2005). ISBN 0-09-179519-2

- Michael Harris. 1992. Rare Ambition: The Crosbies of Newfoundland. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-023220-6

- Wayne Johnston. 1999. The Colony Of Unrequited Dreams, Vintage Canada, Toronto, Ontario. ISBN 978-0-676-97215-3 (0-676-97215-2)

- Kevin Major, As Near To Heaven by Sea, (Toronto, 2001)

- Peter Neary. 1996. Newfoundland in the North Atlantic World, 1929–1949. McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal, Quebec.

- Neary, Peter, and Patrick O'Flaherty. Part of the main : an illustrated history of Newfoundland and Labrador (1983) online free to borrow

- Rowe, Frederick William. A history of Newfoundland and Labrador (1980) online free to borrow

Vintage accounts

- Barnes, Capt. William Morris. When Ships Were Ships (And Not Tin Pots), 1931. Available in digital format at Memorial University site here.

- Birkenhead, Lord. The Story of Newfoundland (2nd ed., 1920) 192pp edition

- Hatton, Joseph and Moses Harvey, Newfoundland: Its History and Present Condition, (London, 1883) complete text online* MacKay, R. A. Newfoundland: Economic, Diplomatic, and Strategic Studies, (1946) online edition

- Millais, John Guille. The Newfoundland Guide Book, 1911: Including Labrador and St. Pierre (1911)? online edition; also reprinted 2009

- Moyles, Robert Gordon, ed. "Complaints is Many and Various, But the Odd Divil Likes It": Nineteenth Century Views of Newfoundland (1975).

- Pedley, Charles.History of Newfoundland, (London, 1863) complete text online

- Prowse, D. W., A History of Newfoundland (1895), current edition 2002, Portugal Cove, Newfoundland: Boulder Publications. complete text online

- Tocque, Philip. Newfoundland as It Was and Is, (London, 1878) complete text online

External links

| Look up newfoundland (island) in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Newfoundland. |

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador.

- Religion, Society, and Culture in Newfoundland and Labrador