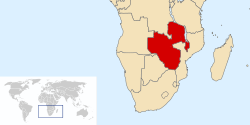

Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a protectorate in south central Africa, formed in 1911 by amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia.[2][3][4][5] It was initially administered, as were the two earlier protectorates, by the British South Africa Company (BSAC), a chartered company, on behalf of the British Government. From 1924, it was administered by the British Government as a protectorate, under similar conditions to other British-administered protectorates, and the special provisions required when it was administered by BSAC were terminated.[5][6]

Northern Rhodesia[1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911–1964 | |||||||||||||

.svg.png) Flag

.svg.png) Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of the United Kingdom; division of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1953–1963) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Livingstone (until 1935) Lusaka (from 1935) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | English (official) Bemba, Nyanja, Tonga and Lozi widely spoken | ||||||||||||

| Government | Protectorate | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

• 1911-1921 | Lawrence Aubrey Wallace | ||||||||||||

• 1959–1964 | Sir Evelyn Hone | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1964 | Kenneth Kaunda | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period · Cold War | ||||||||||||

| 1911 | |||||||||||||

• British protectorate | 1 April 1924 | ||||||||||||

1953–1963 | |||||||||||||

• Independence | 24 October 1964 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Southern Rhodesian pound | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

Although under the BSAC charter, it had features of a charter colony, the BSAC's treaties with local rulers, and British legislation, gave it the status of a protectorate. The territory attracted a relatively small number of European settlers, but from the time they first secured political representation, they agitated for white minority rule, either as a separate entity or associated with Southern Rhodesia and possibly Nyasaland. The mineral wealth of Northern Rhodesia made full amalgamation attractive to Southern Rhodesian politicians, but the British Government preferred a looser association to include Nyasaland. This was intended to protect Africans in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland from discriminatory Southern Rhodesian laws. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland formed in 1953 was intensely unpopular among the vast African majority and its formation hastened calls for majority rule. As a result of this pressure, the country became independent in 1964 as Zambia.[7]

The geographical, as opposed to political, term "Rhodesia" referred to a region generally comprising the areas that are today Zambia and Zimbabwe.[8] From 1964, it only referred to the former Southern Rhodesia.

British South Africa Company

Establishment of BSAC rule

The name "Rhodesia" was derived from Cecil John Rhodes, the British capitalist and empire-builder who was a guiding figure in British expansion north of the Limpopo River into south-central Africa. Rhodes pushed British influence into the region by obtaining mineral rights from local chiefs under questionable treaties. After making a vast fortune in mining in South Africa, it was his ambition to extend the British Empire north, all the way to Cairo if possible, although this was far beyond the resources of any commercial company to achieve. Rhodes' main focus was south of the Zambezi, in Mashonaland and the coastal areas to its east, and when the expected wealth of Mashonaland did not materialise, there was little money left for significant development in the area north of the Zambezi, which he wanted to be held as cheaply as possible.[9] Although Rhodes sent European settlers into the territory that became Southern Rhodesia, he limited his involvement north of the Zambezi to encouraging and financing British expeditions to bring it into the British sphere of influence.

British missionaries had already established themselves in Nyasaland, and in 1890 the British government's Colonial Office sent Harry Johnston to this area, where he proclaimed a protectorate, later named the British Central Africa Protectorate. The charter of BSAC contained only vague limits on the northern extent of the company's sphere of activities, and Rhodes sent emissaries Joseph Thomson and Alfred Sharpe to make treaties with chiefs in the area west of Nyasaland. Rhodes also considered Barotseland as a suitable area for British South Africa Company operations and as a gateway to the copper deposits of Katanga.[10] Lewanika, king of the Lozi people of Barotseland sought European protection because of internal unrest and the threat of Ndebele raids. With the help of François Coillard of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society, he drafted a petition seeking a British protectorate in 1889, but the Colonial Office took no immediate action on it. However, Rhodes sent Frank Elliott Lochner to Barotseland to obtain a concession and offered to pay the expenses of a protectorate there. Lochner told Lewanika that BSAC represented the British government, and on 27 June 1890, Lewanika consented to an exclusive mineral concession. This (the Lochner Concession) gave the company mining rights over the whole area in which Lewanika was paramount ruler in exchange for an annual subsidy and the promise of British protection, a promise that Lochner had no authority to give. However, the BSAC advised the Foreign Office that the Lozi had accepted British protection.[11] As a result, Barotseland was claimed to be within the British sphere of influence under the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1891, although its boundary with Angola was not fixed until 1905.[12]

In 1889, although Britain recognised the rights of the International Association of the Congo to large sections of the Congo basin, which formed the Congo Free State under the personal rule of King Leopold II of the Belgians, it did not accept its effective occupation of Katanga, which was known to have copper and was thought might also have gold. Rhodes, possibly prompted by Harry Johnston, wanted a mineral concession for the BSAC in Katanga. He sent Alfred Sharpe to obtain a treaty from its ruler, Msiri which would grant the concession and create a British protectorate over his kingdom.[13][14] King Leopold II was also interested in Katanga and Rhodes suffered one of his few setbacks when, in April 1891, a Belgian expedition led by Paul Le Marinel obtained Msiri's agreement to Congo Free State personnel entering his territory, which they did in force in 1892. This treaty produced the anomaly of the Congo Pedicle.[15]

Fixing boundaries

The two stages in acquiring territory in Africa after the Congress of Berlin were, firstly, to enter into treaties with local rulers and, secondly, to make bi-lateral treaties with other European powers. By one series of agreements made between 1890 and 1910, Lewanika granted concessions covering a poorly defined area of Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia, and a second series covering a disputed part of North-Eastern Rhodesia was negotiated by Joseph Thomson and Alfred Sharpe with local chiefs in 1890 and 1891.[16]

The Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1891 signed in Lisbon on 11 June 1891 between the United Kingdom and Portugal fixed the boundary between the territories administered by the British South Africa Company in North-Eastern Rhodesia and Portuguese Mozambique. It declared that Barotseland was within the British sphere of influence, and fixed the boundary between the British South Africa Company administered territory of North-Western Rhodesia (now in Zambia), and Portuguese Angola although its boundary with Angola was not marked-out on the ground until later.[17][18] The northern border of the British territory in North-Eastern Rhodesia and the British Central Africa Protectorate was agreed as part of an Anglo-German Convention in 1890, which also fixed the very short boundary between North-Western Rhodesia and German South-West Africa, now Namibia. The boundary between the Congo Free State and British territory was fixed by a treaty in 1894, although there were some minor adjustments up to the 1930s.[19]

Boundaries with other British territories were fixed by Orders-in-Council. The border between the British Central Africa Protectorate and North-Eastern Rhodesia was fixed in 1891 at the drainage divide between Lake Malawi and the Luangwa River,[20] and that between North-Western Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia became the Zambezi River in 1898.[21]

BSAC administration

The area of what became Northern Rhodesia, including Barotseland and land as far as Nyasaland to the east and to Katanga and Lake Tanganyika to the north, was placed under BSAC administration by an Order-in-Council of 9 May 1891, but no BSAC Administrator was sent to Barotseland until 1895, and the first Administrator, Forbes, who remained until 1897, did little to establish an administration there.[22] Before 1911, Northern Rhodesia was administered as two separate territories, Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia. The former was recognised as British territory by the Barotseland and North-Western Rhodesia Order-in-Council of 1899 and the latter by the North-Eastern Rhodesia Order-in-Council of 1900. Both Orders-in-Council regularised the position of the BSAC Administrators, the first of whom were appointed in 1895. Both Order-in-Councils confirmed that the territories had the status of protectorates, with the Colonial Office ultimately responsible for the welfare of their indigenous populations, despite BSAC administration.[23] The Colonial Office retained the ultimate responsibility for these territory, and the High Commissioner for South Africa had the power to approve or reject all BSAC legislation.[24]

At first, Harry Johnston in Nyasaland was the local representative of the Colonial Office and the High Commissioner. Rhodes financed much of the British presence in Nyasaland and worked closely with Johnston and his successor, Alfred Sharpe, so he could use them as emissaries and their Nyasaland troops as enforcers, particularly in North-Eastern Rhodesia. This territory and North-Western Rhodesia were considered by Rhodes and his colonisers to be a "tropical dependency" rather than a northward extension of white-settler controlled southern Africa. In 1895, Rhodes asked his American scout Frederick Russell Burnham to look for minerals and ways to improve river navigation in the region, and it was during this trek that Burnham discovered major copper deposits along the Kafue River.[25] In 1911 the BSAC merged the two territories as 'Northern Rhodesia'.[26]

Under British South Africa Company rule, the company-appointed Administrator had powers similar to those of the governor of a British colony or protectorate, except that certain decisions of the Administrator affecting Europeans had to be approved by the High Commissioner for South Africa to be valid. The High Commissioner could also make, alter or repeal proclamations for the administration of justice, taxation, and public order without reference to the Administrator, although this power was never used.[27] In this period the Administrator was assisted neither by an Executive Council nor a Legislative council, as was common in British-ruled territories. There was an Advisory Council, which fulfilled most of the functions of such bodies, and which until 1917 consisted entirely of senior officials. There was no obligation for the company to form a body to consult residents, but after 1917 nominees were added to represent the small European minority: Northern Rhodesia had no elected representation while under BSAC rule.[28] There were five nominated members: four represented the former North-Western Rhodesia and one represented North-Eastern Rhodesia.

Hut tax was first collected in North-Eastern Rhodesia in 1901 and was slowly extended through North-Western Rhodesia between 1904 and 1913. It was charged at different rates in different districts but was supposed to be equivalent to two months' wages, to encourage or force local Africans into the system of wage labour. Its introduction generally caused little unrest, and any protests were quickly suppressed. Before 1920, it was commonly charged at five shillings a year, but in 1920 the rate of hut tax was sharply increased, and often doubled, to provide more workers for the Southern Rhodesian mines, particularly the coal mines of Wankie.[29] At this time the Company considered the principal economic benefit of Northern Rhodesia to be as a reservoir for migrant labour which could be called upon for Southern Rhodesia.

Law and security

British common law became the basis of the administration of Southern and Northern Rhodesia, unlike Roman Dutch law which applied in South Africa. In 1889, the British South African Company was given the power to establish a police force and administer justice within Northern Rhodesia. In the case of African natives appearing before courts, the Company was instructed to have regard to the customs and laws of their tribe or nation. An Order in Council of 1900 created the High Court of North-Eastern Rhodesia which took control of civil and criminal justice; it was not until 1906 that North-Western Rhodesia received the same. In 1911 the two were amalgamated into the High Court of Northern Rhodesia.

The British South African Company considered that its territory north of the Zambezi was more suitable for a largely African police force than a European one. However, at first, the British South Africa Police patrolled the north of the Zambezi in North Western Rhodesia, although its European troops were expensive and prone to diseases. This force and its replacements were paramilitaries, although there was a small force of European civil police in the towns. The British South Africa Police were replaced by the Barotse Native Police force, which was formed in 1902 (other sources date this as 1899 or 1901). This had a high proportion of European NCOs as well as all European officers and was merged with the civil police to form the Northern Rhodesia Police in 1911. Initially, Harry Johnston in the British Central Africa Protectorate had responsibility for North Eastern Rhodesia, and Central Africa forces including Sikh and African troops were used there until 1899. Until 1903, local magistrates recruited their own local police, but in that year a North Eastern Rhodesia Constabulary was formed, which had only a few white officers; all its NCOs and troopers were African. This was also merged into the Northern Rhodesia Police in 1912, which then numbered only 18 European and 775 African in six companies, divided between the headquarters of the various districts.[30][31]

Railway developments

The British South Africa Company was responsible for building the Rhodesian railway system in the period of primary construction which ended in 1911 when the main line through Northern Rhodesia crossed the Congo border to reach the Katanga copper mines. Rhodes' original intention was for a railway extending across the Zambezi to Lake Tanganyika, but when little gold was found in Mashonaland, he accepted that the scheme to reach Lake Tanganyika had no economic justification. Railways built by private companies needed traffic that can pay high freight rates, such as large quantities of minerals.[32]

A line from Kimberley reached Bulawayo in 1897; this was extended to cross the Victoria Falls in 1902. The next section was through Livingstone to Broken Hill, which the railway reached in 1906. The British South Africa Company had been assured that there would be plentiful traffic from its lead and zinc mines, but this did not materialise because of technical mining problems. The railway could not meet the costs of the construction loans, and the only area likely to generate sufficient mineral traffic to relieve these debts was Katanga. Initially, the Congo Free State had concluded that Katanga's copper deposits were not rich enough to justify the capital cost of building a railway to the coast, but expeditions between 1899 and 1901 proved their value. Copper deposits found in Northern Rhodesia before the First World War proved uneconomic to develop.[33]

In 1906, Union Minière du Haut Katanga was formed to exploit the Katanga mines. King Leopold wanted a railway entirely in Congolese territory, linked to the Congo River, but in 1908, he agreed with the British South Africa Company to continue the Rhodesian railway to Elizabethville and the mines. Between 1912, when full-scale copper production began, until 1928 when a Congolese line was completed, almost all of Katanga's copper was shipped over the Rhodesian network. The railway's revenue from Katanga copper enabled it to carry other goods at low rates. Large-scale development of the Copperbelt only began in the late 1920s, with an increasing world market for copper. Transport was no problem as only short branches had to be built to connect the Copperbelt to the main line.[34]

The end of BSAC rule

Almost from the start of European settlement, the settlers in Northern Rhodesia were hostile to the BSAC administration and its commercial position. The company opposed the settlers' political aspirations and refused to allow them to elect representatives to the Advisory Council, limiting them to a few nominated members.[35] Following a judgement by the Privy Council that the land in Southern Rhodesia belonged to the British Crown not BSAC, opinion among settlers in Southern Rhodesia turned to favour responsible government and in 1923 this was granted. This left Northern Rhodesia in a difficult position since the British South Africa Company had believed it owned the land in both territories and some settlers suggested that the ownership in Northern Rhodesia should also be referred to the Privy Council. However, the British South Africa Company insisted that its claims were unchallengeable and persuaded the United Kingdom government to enter into direct negotiations over the future administration of Northern Rhodesia.

As a result, a settlement was achieved by which Northern Rhodesia remained a protectorate but came under the British government, with its administrative machinery taken over by the Colonial Office, while the British South Africa Company retained extensive areas of freehold property and the protectorate's mineral rights. It was also agreed that half of the proceeds of land sales in the former North-Western Rhodesia would go to the Company. On 1 April 1924, Herbert Stanley was appointed as Governor and Northern Rhodesia became an official Protectorate of the United Kingdom, with capital in Livingstone. The capital was moved to Lusaka in 1935.

Under the Administration of the British South Africa Company, the Administrator had similar powers to those of a colonial governor, except that certain powers were reserved to the High Commissioner for South Africa. There was neither an Executive Council nor a legislative council, but only an Advisory Council, consisting entirely of nominees. The Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1924[6] transferred to the Governor any power or jurisdiction previously held by the Administrator or vested in the High Commissioner for South Africa. The Order also provided for an Executive Council consisting of six ex-officio senior officials and any other official or unofficial members Governor wished to appoint. At the same time, a legislative council was established, consisting of the Governor and up to nine official members, and five unofficial members who were to be elected by the small European minority consisting of only 4,000 people only, as none of the African population had the right to vote.[27]

The Colonial Period

Mining developments

The most important factor in the colony's economy was copper. Ancient surface copper workings were known at Kansanshi (near Solwezi), Bwana Mkubwa and Luanshya, all on what later became known as the Copperbelt and exploration in 1895 by the British South Africa Company's celebrated American scout, Frederick Russell Burnham, who led and oversaw the massive Northern Territories (BSA) Exploration Co. expedition first established for Westerners that major copper deposits existed in Central Africa.[36] Along the Kafue River in then Northern Rhodesia, Burnham saw many similarities to copper deposits he had worked in the United States, and he encountered natives wearing copper bracelets.[37] Later, the British South Africa Company built towns along the river and a railway to transport the copper through Mozambique.[38]

BSAC claimed to own mineral rights over the whole of Northern Rhodesia under concessions granted between 1890 and 1910 by Lewanika covering a poorly defined area of North-Western Rhodesia or negotiated by Joseph Thomson and Alfred Sharpe in 1890 and 1891 with local chiefs in a disputed area of North-Eastern Rhodesia. This claim was accepted by the British Government.[16] After the Charter ended, BSAC joined a group of nine South African and British companies which financed the development of Nchanga Mines, to prevent them falling under US control. However, its main concern was to receive royalties.[39]

However significant they were, these copper deposits could not be exploited commercially until the Southern Rhodesian railway had extended across the Zambezi and continued northward, to reach the Belgian Congo border, which it did in 1909. By that time, mining had started in Katanga, where rich copper oxide ores occurred near the surface. In Northern Rhodesia, the surface ores were of poorer quality, and copper was only worked intermittently at Bwana Mkubwa until in 1924 rich copper sulphide ores were discovered about 100 feet below the surface.[40] Prior to 1924, there had not been significant exploitation of Northern Rhodesia's mineral resources: there was some cattle farming in Barotseland, but Northern Rhodesia had attracted little white settlement, in contrast to its southern neighbour. Unlike Southern Rhodesia, which had seen a flood of fortune-seeking prospectors seeking to set up independent mines, Northern Rhodesia's mining policy was to agree large-scale deals with major commercial mining companies.

Large-scale mining on the Northern Rhodesian Copperbelt started after 1924 and was mainly financed from the United States of America and South Africa. Chester Beatty's and Sir Edmund Davis's Selection Trust already had an interest in the fairly small Bwana Mkubwa copper mine, which had opened in 1901 on the site of ancient mineral workings at the southern end of the Copperbelt, and Beatty was responsible for the development of the Roan Antelope mine at Luanshya in 1926. Copper was becoming much more valuable as more of it was needed for electrical components and the motor industry. In 1927, Beatty sold a one-third interest in Roan Antelope to the American Metal Company (AMC), whose interests were in refining and selling metals, and in 1928 he formed Rhodesian Selection Trust (RST – later renamed Roan Selection Trust) to finance further mining developments. Beatty then sold his controlling interest in RST to AMC in 1930, becoming AMC's largest shareholder. AMC's commitment to RST allowed it to bring the Mufulira mine into partial production in 1930, although it only became fully operational in 1933, because of the Great Depression.[41][42]

South African interest in the Copperbelt was led the Anglo American Corporation, which gained an interest in the Bwana Mkubwa company in 1924 and acquired a one-third interest in Mufulira in 1928. Also in 1928, Anglo American acquired control of the Nkana mine at Kitwe and formed Rhodesian Anglo American, whose other shareholders included US and South African finance houses and the British South Africa Company (BSAC). As BSAC exchanged its own shares for Rhodesian Anglo American ones, Rhodesian Anglo American now became a major shareholder in BSAC. Both Roan Antelope and Nkana started commercial production in 1931.[43][44]

At first, very little British capital was invested in the Copperbelt. However, in 1929 it seemed possible that a fourth source of copper, Nchanga Mines, might fall under US control: as an American cartel which sought to restrict supply to increase prices then already controlled three-quarters of world copper production, the British government encouraged a group of nine "British" companies to finance Nchanga. This group was dominated by Rhodesian Anglo American, so truly British participation was still limited. In 1931 the ownership of Bwana Mkubwa and Nchanga was amalgamated into the Rhokana Corporation, in which Rhodesian Anglo American also predominated. The situation in 1931 was that Rhodesian Selection Trust (RST) owned Roan Antelope and a dominant interest in Mufulira, while Rhokana Corporation owned the remained of Mufulira, Nkana, Nchanga and Bwana Mkubwa. The shareholding structure of RST and particularly of Rhokana was complex.[45][46]

While at first the existence this cartel encouraged investment, consumers sought alternative and cheaper materials and with the economic downturn, the price of copper crashed in 1931. An international agreement restricted output. This caused a catastrophe in Northern Rhodesia where many employees were sacked and put an end to hopes which many Europeans had held of turning Northern Rhodesia into another white dominion like Southern Rhodesia. Many settlers took this opportunity to move back to Southern Rhodesia, while Africans returned to their farms.

Economic recovery

Despite the economic crash, large firms were still able to maintain a profit. The fact that unemployed workers had left meant there were no increases in taxation, and labour costs remained low. At a 1932 conference of copper producers in New York, the Rhodesian companies objected to further market intervention, and when no agreement could be made, the previous restrictions on competition lapsed. This placed the Northern Rhodesians in a very powerful position. Meanwhile, the British South Africa Company sold its remaining Southern Rhodesian holdings to the Southern Rhodesian government in 1933 giving it the capital to invest in developing other mines. It negotiated an agreement between Rhodesia Railways and the copper mine companies for exclusive use and used resources freed up to buy a major stake in the Anglo American Corporation. By the end of the 1930s, Northern Rhodesian copper mining was booming.

Legislative Council

Pre-war

When Northern Rhodesia became a Protectorate under the British Empire on 1 April 1924, a Legislative Council was established on which the Governor of Northern Rhodesia sat ex officio as Presiding Officer. The initial council consisted entirely of nominated members, as no procedure existed at the time for holding elections. However, the members were divided between the "official members" who held executive posts in the administration of the Protectorate, and the "unofficial members" who held no posts.[47]

In 1926, a system of election was worked out and the first election was held for five elected unofficial members, who took their seats together with nine nominated official members. An elector in Northern Rhodesia had to be a United Kingdom citizen, a requirement which practically ruled out Africans who were British Protected Persons. In addition, would-be electors were required to fill in an application form in English, and to have an annual income of at least £200 or occupy immovable property worth £250 (tribal or community occupation of such property was specifically excluded).[48]

In 1929, the number of unofficial members was increased to seven. This failed to meet settler aspirations and in 1937 their members demanded parity if numbers with the nine official members, and seats on the Executive Council, until then wholly composed of officials: this demand was rejected. In 1938, there was the first acknowledgement of the need to represent the opinions of Africans, and one nominated unofficial European member was added for this purpose, replacing one of the nominated officials, so that the official and unofficial members each numbered eight.[49] In 1941 one additional member was added to both the nominated officials and the elected unofficials, for a total of ten unofficials (nine elected) and nine nominated officials.

Post-war

In 1945, there was an increase in the number of unofficial European members representing Africans from one to three, and an additional two nominated unofficials were introduced for a total of five. From 1948, the African Representative Council recommended two African unofficial members for nomination by the Governor.[50] 1948 saw the replacement of the Governor by a Speaker, who also sat ex officio, and the introduction of two members nominated on the advice of the African Representative Council.

An Order-in-Council coming into effect on 31 December 1953 provided for a new Legislative Council to consist of a Speaker ex officio, eight nominated officials, twelve elected unofficials, four African unofficial members nominated by the Governor on the advice the African Representative Council, and two nominated unofficial European members representing the interests of Africans.[51] The nominated officials were identified as the Chief Secretary, Attorney General, Financial Secretary, and Secretary for Native Affairs, and four others.

1959 Order-in-Council

1959 saw a large increase in the proportion of elected members. The Legislative Council then consisted of the Speaker and 30 members. All but eight of these members were to be elected: the eight nominated were the same four named posts as before, two others, and two nominated unofficial members (who were not specifically responsible for African interests). These two members were retained to provide that there were some members who could be called upon for Ministerial duties if there were too few elected members willing to do so.

The 22 elected members were organised in such a way as to ensure that there were eight African and 14 Europeans. The electoral roll was divided into 'General' and 'Special' with Special voters having much lower financial requirements than General voters so that the majority of Special voters were Africans (the nationality requirement had been varied so that British Protected Persons were eligible to vote). In the towns in which a majority of Europeans lived, there were twelve constituencies; special voters could have no more than one-third of the influence on the total.

In the rural areas where most Africans lived, six special constituencies were drawn. Both general and special voters participated in the elections and their votes counted for equal weight, although the majority of voters were Africans. In the special constituency areas, there were two composite 'Reserved European seats', in which special voters were restricted to one-third of the influence. There were also two 'Reserved African seats' in the areas of the ordinary constituencies, although all votes counted in full.[52]

Law

Before the end of BSAC administration, Northern Rhodesian law was in conformity with the laws of England and Wales and its High Court of Northern Rhodesia was ultimately subordinate to those of the United Kingdom. This continued after 1924; all United Kingdom statutes in force on 17 August 1911 were applied to Northern Rhodesia, together with those of later years if specific to the Protectorate. Where Africans were parties before courts, Native law and customs were applied, except if they were "repugnant to natural justice or morality", or inconsistent with any other law in force.[53]

Subsidiary Courts

Below the High Court were Magistrates' Courts which fell into four classes:

- Courts of Provincial Commissioners, Senior Resident Magistrates and Resident Magistrates. In criminal matters, such courts could impose sentences of imprisonment for up to three years; in civil matters, they were limited to awards of £200 and for recovery of land worth up to £144 annual rent.

- Courts of District Commissioners. In criminal matters, they could impose sentences of imprisonment for up to one year without confirmation by the High Court; they could also impose up to three years' imprisonment with the High Court's consent. Their civil jurisdiction was limited to £100.

- Courts of District Officers.

- Courts of Cadets attached to the Provincial Administration.

Criminal trials for treason, murder and manslaughter, or attempts and conspiracies to commit them, were reserved for the High Court. Civil matters relating to constitutional issues, wills and marriages were also restricted to the High Court.

Native Courts

The Native Courts Ordinance 1937 allowed the Governor to issue a warrant recognising native courts. Their jurisdiction only covered natives but extended to criminal and civil jurisdiction. Native courts were not allowed to impose the death penalty, nor try witchcraft without permission. There was also provision for a Native Court of Appeal, but if not established, appeal was to the Provincial Commissioner and thence to the High Court.

Chief Justices of North-Eastern Rhodesia

| Incumbent | Tenure | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | ||

| Sir Leicester Paul Beaufort | 1901 | 1911 | |

Chief Justices of Northern Rhodesia

| Incumbent | Tenure | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | ||

| Cyril Gerard Brooke Francis[54] | 1941 | afterwards Chief Justice of Bermuda, 1941 | |

| Sir Herbert Charles Fahie Cox [55][56] | 1945 | 1951 | afterwards Chief Justice of Tanganyika |

| Sir Arthur Werner Lewey [57] | 1951 | 1955 | |

| Sir (Edward) Peter Stubbs Bell | 1955 | 1957 | Died in office |

| John Bowes Griffin | 1957 | 1957 | acting Chief Justice |

| Sir George Paterson | 1957 | 1961 | |

| Sir Diarmaid William Conroy | 1961 | 1964 | afterwards Chief Justice of Zambia, 1964–1965 |

Governing the people

From the 1890s and until after the end of BSAC administration, a policy of Direct Rule over Africans was operated, within the limits of what was possible with very small numbers of white District Officers. Except in Barotseland, these officers deprived traditional chiefs of their powers of administering justice, and deposed troublesome ones, although most chiefs accepted their reduced role as local agents of the District Officers. By the late 1920s, the idea of Indirect Rule that Lord Lugard had proposed in "The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa" had gained favour. Lugard suggested that, in colonies where climate and geography precluded extensive European settlement, African interests should be recognised as paramount and the development of such colonies must benefit their indigenous population as well as the economic interests of the colonial power. However, what was introduced into Northern Rhodesia in 1930 as a policy of Indirect Rule was little different in practice to the previous policy. Although some legitimate traditional chiefs and other appointed chiefs and headmen were nominated as Native Authorities, they had limited judicial powers and very limited financial resources to build up any institutions of self-government within their communities. Apart from in Barotseland, the District Officers still retained most of their former powers, and used the Native Authorities as intermediaries.[58][59]

In June 1930, the Colonial Secretary of the Labour Government, Lord Passfield, published his Memorandum on Native Policy in East and Central Africa. His statement of colonial policy was an emphatic reassertion of the principle of paramountcy of African interests, which his predecessor as Colonial Secretary, the Conservative Leo Amery, has attempted to water-down in 1927 when setting up the Hilton Young Commission. Passfield's Memorandum stated that no further white minority governments would be permitted, dismissing settler aspirations of self-government in Kenya and Northern Rhodesia. This turned Northern Rhodesian Europeans against association with East Africa towards union with Southern Rhodesia. In 1933, a substantial minority in the Northern Rhodesian legislature favoured amalgamation with Southern Rhodesia, despite vigorous African opposition. However, the majority of settlers were still cautious about being marginalised by the much greater numbers of Europeans in Southern Rhodesia.[60][61]

From 1943, six Provincial Councils were set up to form a second tier of African representative institutions above the Native Authorities. These were purely advisory bodies, whose advice the Provincial Commissioner need not accept. Most of the members of the Provincial Councils were rural and many were chiefs, but some educated urban Africans were included. In 1946, a third tier was added with the formation of an African Representative Council for the whole protectorate, whose members were nominated by the Provincial Councils. The African Representative Council was also largely advisory, but was later able to make recommendations for Africans to be nominated as members of the Legislative Council.[62]

Land policies

In Northern Rhodesia, the British South Africa Company claimed ownership of all the unalienated land in the territory, and the right to alienate it. Europeans occupied land along the line of the railway and near the towns, but at first there was no land shortage, as the population density was low and the European population was small. In 1913, BSAC drew up plans for Native Reserves along Southern Rhodesian lines, outside which Africans would have no right to own or occupy land, but these plans were not put into effect under company administration. However, reserves were created in 1928 and 1929 in the northern and eastern parts of the protectorate, and about half the land adjacent to the line of the main railway line was reserved for European settlement and farming. In 1938, it was reported that the Native Reserves were overcrowded, while much of the land reserved for Europeans was unoccupied and unused[63]

In 1918, the Privy Council of the United Kingdom had rejected the British South Africa Company claims to unalienated land in Southern Rhodesia, and this raised questions about the company's claim to unalienated land north of the Zambezi. However, the company's claim in Northern Rhodesia was based on concessions granted rather than conquest and, although a Northern Rhodesian parliamentary Committee in 1921 recommended that these claims also should be referred to the Privy Council, the British government preferred to negotiate an overall settlement for the end of BSAC administration in Northern Rhodesia. This effectively acknowledged the company's claim.[64] Under an Agreement of 29 September 1923, the Northern Rhodesian government took over the entire control of lands previously controlled by BSAC from 1 April 1924, paying the company half the net rents and the proceeds of certain land sales.[65]

Opposition to minority rule

Firstly, independent African churches such as the Ethiopian Church in Barotseland, Kitawala or the Watchtower movement and others rejected European missionary control and promoted Millennialism doctrines that the authorities considered seditious. They were not generally politically active, but the Watchtower movement was supposedly involved in the 1935 Copperbelt riots, probably incorrectly. Secondly, Africans educated by missions or abroad sought social, economic and political advancement through voluntary associations, often called "Welfare Associations". Their protests were muted until the early 1930s, and concentrated on improving African education and agriculture, with political representation a distant aspiration. However, several of the Welfare Associations on the Copperbelt were involved in the 1935 disturbances.[66]

Hut tax was gradually introduced to different areas of Northern Rhodesia between 1901 and 1913. Its introduction generally caused little unrest, but in 1909–10 the Gwembe branch of the Tonga people staged a relatively non-violent protest against its introduction, which was severely suppressed. A sharp increase in the rate of Hut tax in 1920 caused unrest, as did the 1935 increase in the tax rate on the Copperbelt.[67]

In 1935, the Northern Rhodesian government proposed to increase the rates of tax paid by African miners working on the Copperbelt, while reducing it in rural areas. Although the Provincial Commissioners had been told about the change on 11 January 1935, it was not until 20 May that the Native Tax Amendment Ordinance was signed, with rates implemented as of 1 January 1935. This retrospective increase outraged the miners, who already had grievances about low pay and poor conditions, and also with the Pass laws which had been introduced in 1927 and required Africans to have permits to live and work on the Copperbelt. It provoked an all-out Copperbelt strike which lasted from 22 May to 25 May in three of the four mines in the area, namely Mufulira, Nkana and Roan Antelope. British South Africa Police were sent from Southern Rhodesia to Nkana to suppress it. When, on 29 May, police in Luanshya attempted to disperse a group of Africans, violence erupted and six Africans were shot dead. The loss of life shocked both sides and the strike was suspended while a Commission of Inquiry was set up. It concluded that the way the increases were announced was the key factor, and that if they had been introduced calmly, they would have been accepted.[68]

One effect of the strike was the establishment of tribal elders' advisory councils for Africans across the Copperbelt, following a system introduced at the Roan Antelope mine. These councils acted as minor courts, referring other matters to the mine compound manager or district organiser. Native courts operated outside the urban areas and eventually these were introduced to the towns. Mufulira was the first, in 1938, and by the end of 1940 they existed in Kitwe, Luanshya, Ndola and Chingola on the Copperbelt, Lusaka and Broken Hill in the centre of the country, and Livingstone on the border with Southern Rhodesia. Simultaneously, African Urban Advisory Councils were established in the main Copperbelt towns. Relations between Africans and Europeans were often strained.[69]

A second round of labour hostilities broke out in March 1940. This was prompted by successful wildcat strike action by European miners at two Copperbelt mines, who demanded increased basic pay, a war bonus and a closed shop to prevent the advancement of African miners. The European strikers' demands were largely conceded, including an agreement on preventing the permanent "dilution of labour". This was followed by a refusal to grant a proportionate increase of pay to African miners, who then went on strike despite the offer of slightly increased bonus payments. The government urged the mine-owners to increase the African miners' pay, but following a confrontation between workers collecting their pay and diehard strikers, it also tried to force the miners to return to work, using troops of the Northern Rhodesian Regiment. In the violence that followed, the troops fired on the strikers, causing 13 deaths immediately and four later. The Colonial Secretary forced the governor to hold a Commission of Inquiry, which found that conditions at Nkana and Mufulira had little changed from 1935, although at Nchanga and Roan Antelope no strike had happened. It recommended increases in pay and improvements in conditions, which the mine-owners agreed, and also that African miners should be eligible for jobs previously reserved for European miners. This last recommendation was not implemented then, but was gradually introduced after 1943.[70][71]

World War II

During World War II, Northern Rhodesian military units participated on the side of the United Kingdom. Specifically, Northern Rhodesian forces were involved in the East African Campaign, the Battle of Madagascar and in Burma. Later in the war, the British government's Ministry of Supply entered into agreements with the Northern Rhodesian and Canadian copper mines to supply all the copper needed by the armed forces for set prices. This removed free competition and therefore kept prices down; as British companies, the main copper producers were also subject to the Excess Profits Tax. However they did have a guaranteed market, and in 1943 the Ministry of Supply paid half of the cost of an expansion programme planned for the Nchanga mine.

There was an election in 1941; Roy Welensky, a leader in the Rhodesian Railway Workers' Union who had been elected in 1938, set up the Northern Rhodesian Labour Party as a party favouring amalgamation earlier in the year. All five candidates of the party were elected. This development was spotted in London where Labour Party MPs were concerned that the demand, if granted, would diminish the position of the Africans of Northern Rhodesia. Welensky led a move in the Legislative Council to restrict the British South Africa Company's mineral rights which garnered African support; the Company agreed in 1949 to assign 20% of its revenues to the Government, and to transfer all its remaining rights in 1986.

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Early attempts at association

As early as 1915, the British South Africa Company proposed amalgamating Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia, but this was rejected by the Southern Rhodesian legislature in 1917, as it might have prevented Southern Rhodesia obtaining self-government.[72] This option was again rejected in 1921, for the same reason. After the Southern Rhodesian electorate voted for self-determination in 1922, this objection ceased, and in 1927 the Conservative Colonial Secretary, Leo Amery gave Southern Rhodesia settlers the impression that he supported their claim to acquire the more productive parts of Northern Rhodesia.[73]

At the end of the First World War, the European population of Northern Rhodesia was tiny, about 3,000 compared with ten times as many in Southern Rhodesia, but it increased rapidly after the discovery of the Copperbelt in the 1920s. Northern Rhodesian settlers wanted self-government for the European minority electorate, separate from Southern Rhodesia. However, once the British government appeared to reject the idea of further white minority governments in Africa, talk of amalgamation resumed.[74]

In 1927, the British government appointed the Hilton Young Commission on the possible closer union of the British territories in East and Central Africa. Its majority thought that Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland should seek closer links with East Africa, but the minority report favoured linking these two territories with Southern Rhodesia on economic grounds. Even before the Commission's report was published, there were discussions between the Northern Rhodesian settlers and the Southern Rhodesian government on the terms of a total union of the two Rhodesias as a single colony. Northern Rhodesian settlers were only prepared to join Southern Rhodesia if there were no other way to achieve minority rule.[75][76] When Northern Rhodesia's mining industry suffered a major downturn in the 1930s, its representatives pushed for amalgamation in January 1936 at Victoria Falls, but the Southern Rhodesian Labour Party who blocked it, because the British government objected to Southern Rhodesian policies of job reservation and segregation being applied in the north.[77]

Shortly after the Copperbelt strike of 1935 there was an election to the legislative council, in which all candidates supported investigating the amalgamation of Northern and Southern Rhodesia. After a conference at Victoria Falls between the elected members and representatives of the Southern Rhodesian political parties in January 1936 resolved in favour of amalgamation "under a constitution conferring the right of complete self-government". The United Kingdom government initially refused to set up a Royal Commission, but following pressure from Europeans in both the Rhodesias, particularly from Godfrey Huggins, who had been the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia since 1933, the British government agreed in 1937 to set up one, as the Bledisloe Commission, whose chairman was Lord Bledisloe. Its terms if reference were to consider a possible closer association between the two Rhodesias and Nyasaland.[78]

Federation implemented

The Bledisloe Commission reported in March 1939, and suggested that Africans could benefit socially and economically from European enterprise. However, it thought that two major changes would be necessary: firstly, to moderate Southern Rhodesian racial policies, and secondly, to give some form of representation of African interests in the legislatures of each territory.[79] The Commission considered the complete amalgamation of the three territories, and thought that it would be more difficult to plan future development in a looser federal union. It did not favour an alternative under which Southern Rhodesia would absorb the Copperbelt. Despite the almost unanimous African opposition to amalgamation with Southern Rhodesia, the Commission advocated it at some time in the future, However, a majority of Commission members ruled amalgamation out as an immediate possibility, because of African concerns and objections. This majority favoured an early union of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland into one unit which would co-operate economically with Southern Rhodesia as a possible first step to uniting all three territories later.[80][81][82] Northern Rhodesia's white population were severely disappointed, but the outbreak of World War II fundamentally changed the economic and political situation, as Northern Rhodesian copper became a vital resource in winning the war.

During the Second World War, co-operation between the three territories increased with a joint secretariat in 1941 and an advisory Central African Council in 1945, made up of the three governors and one leading European politician from each territory. Post-war British governments were persuaded that closer association in Central Africa would cut costs, and they agreed to a federal solution, not the full amalgamation that the Southern Rhodesian government preferred. The first post-war Colonial Secretary from 1946 to 1950, Arthur Creech Jones of the Labour Party, was reluctant to discuss any plans for amalgamation with Godfrey Huggins, the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia because of opposition from Africans and from within his own party. He did not entirely rule out federation, which had been proposed by a conference held at Victoria Falls in 1949 between the Southern Rhodesian government, and the elected, or "unofficial" members of the Northern Rhodesia Legislative Council led by Roy Welensky, without any Africans present. It was left to his successor in post in 1950 to 1951, James Griffiths, to begin exploratory talks with Huggins and Welensky representing the white minorities of both Rhodesias, subject to the opinion of the majority African populations being ascertained. After a change in the British government in 1951, the incoming Conservative Colonial Secretary, Oliver Lyttelton removed the condition of sounding out African opinion in November 1951 and pushed ahead against strong African opposition. After further revisions of the proposals for federation, agreement was reached. Following a positive referendum result in Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia joined the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland when it was created in 1953.[83][84]

Opposition to Federation

In 1946, the Federation of African Welfare Societies was formed, uniting the Welfare Societies that had been set up by educated Africans in towns in the 1930s to discuss local affairs in English. In 1948 the Federation changed its name to the Northern Rhodesia Congress and Godwin Mbikusita Lewanika, who had an aristocratic Barotse background, became its first president. In the late 1940s several local trade unions representing African miners merged to form the Northern Rhodesian African Mineworkers' Union. Under Mbikusita Lewanika, Congress gradually developed as a political force. It had some radical policies, but Mbikusita Lewanika favoured gradualism and dialogue with the settler minority. In 1950 and 1951 he failed to deliver a strong anti-Federation message and in 1951 Mbikusita Lewanika was voted out of office and replaced by the more radical Harry Nkumbula.[85]

Harry Nkumbula, a schoolteacher from Kitwe, had been given a scholarship to study in London, where he met Hastings Banda. The main African objections to the Federation were summed up in a joint memorandum prepared by Nkumbula for Northern Rhodesia and Banda for Nyasaland in 1950, shortly before Nkumbula returned to Northern Rhodesia. These objections were that political domination by the white minority of Southern Rhodesia would prevent greater African political participation, and that control by Southern Rhodesian politicians would lead to an extension of racial discrimination and segregation. Nkumbula returned to Northern Rhodesia in 1950 to fight against Federation and against Mbikusita Lewanika's leadership of Congress. His radicalism caused some chiefs and conservatives to withdraw their support from Congress, but the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress, as the party was renamed in 1951, was able to persuade the African Representative Council to recommend two of its members to be African-nominated members of the Legislative Council in 1951.[85] Shortly after its formation, the Federal government attempted to take control of African affairs from the British Colonial Office, proving the fears of Nkumbula and Banda were justified. It also scaled back the fairly modest British post-war proposals for African development.[86]

The Northern Rhodesian African National Congress had been a rather small, largely urban, party under Mbikusita Lewanika, but Nkumbula used opposition to Federation to increase its membership. In 1951, Kenneth Kaunda, formerly a teacher, became Organising Secretary for Congress in the Northern Province, and in 1953 he moved to Lusaka as Secretary General of Congress, under Nkumbula's presidency. The efforts of Congress, including a failed general strike in March 1953, could not prevent the imposition of Federation, and apart from some urban protests, it was sullenly accepted by the African majority. Both Kaunda and Nkumbula began to advocate self-government under African majority rule, rather than just increased African representation in the existing colonial institutions. In addition to demanding the break-up of Federation, Congress targeted local grievances, such as the "colour bar", the denial of certain jobs or services to Africans and low pay and poor conditions for African workers. Kaunda was prominent in organising boycotts and sit-ins, but in 1955 both he and Nkumbula were imprisoned for two months.[87]

Imprisonment radicalised Kaunda, who intensified the campaign of economic boycotts and disobedience on his release, but it had the opposite effect on Nkumbula, who had already acted indecisively over the 1953 general strike. Nkumbula's leadership became increasingly autocratic and it was alleged he was using party funds for his own benefit. However, Kaunda continued to support Nkumbula even though in 1956 Nkumbula attempted to end the campaign against the colour bar. Kaunda's estrangement from Nkumbula grew when he spent six months in Britain working with the Labour party on decolonisation, but the final rupture came only in October 1958 when Nkumbula tried to purge Congress of his opponents and assume sweeping powers over the party. In that month, Kaunda and most of the younger, more radical members left to form the Zambia African National Congress, with Kaunda as president.[88]

End of Federation and independence

After the defection of Kaunda and the radicals, Nkumbula decided that the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress would contest the Legislative Council elections to be held under the 1959 Order-in-Council in October 1959. To increase the chances of Congress, he entered into electoral pacts with white liberals. Kaunda and the Zambia African National Congress planned to boycott these elections, regarding the 1959 franchise as racially biased.[89] However, before the elections a State of emergency had been declared in Nyasaland and Banda and many of his followers had been detained without trial, following claims that they had planned the indiscriminate killing of Europeans and Asians, and of African opponents, the so-called "murder plot". Shortly afterwards, on 12 March 1959, the governor of Northern Rhodesia also declared a State of emergency there, arrested 45 Zambia African National Congress including Kaunda and banned the party. Kaunda later received a 19-month prison sentence for conspiracy, although no credible evidence of conspiracy was produced. The declaration of States of emergency in both Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland marked the end of attempts by their nationalist parties to work within the colonial system, and the start of a push for immediate and full independence.[90]

Although Nkumbula and his party won several seats in the October 1959 elections, he made little use of Kaunda's enforced absence and managed to alienate another section of the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress who, with former Zambia African National Congress members, formed the United National Independence Party in October 1959. When Kaunda was released from prison in January 1960, he assumed its leadership. Nkumbula and what was left of Congress retained support in the south of the country, where he had always maintained a strong following among the Ila and plateau Tonga peoples, but the United National Independence Party was dominant elsewhere.[91][92]

Roy Welensky, a Northern Rhodesian settler who was the Federal Prime Minister from November 1956 had convinced Alan Lennox-Boyd, Colonial Secretary from 1954 to 1959, to support Federation and to agree that the pace of African advancement would be gradual. This remained the view of the British cabinet under Harold Macmillan until after the declaration of the States of emergency, when it decided to set up a Royal Commission on the future of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland to be held in 1960. This became the Monckton Commission, which concluded that the Federation could not be maintained except by force or through massive changes in racial legislation. It advocated a majority of African members in the Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesian legislatures and giving these territories the option to leave the Federation after five years.[93][94]

Iain Macleod replaced Lennox-Boyd as Colonial Secretary in October 1959: he soon released Banda and negotiated a constitution for responsible government for Nyasaland with him, to follow elections in 1961 that would lead to an African majority on the Legislative Council. However, Macleod was more cautious on political change in Northern Rhodesia. A plan for a Legislative Council with an African majority (16 African members to 14 Europeans) was strongly opposed by Welensky, and under pressure from cabinet colleagues, Macleod accepted Welensky's proposal for a council of 45 members, 15 of whom would be elected by a largely African electoral roll, 15 by a largely European roll, 14 by both rolls jointly and 1 by Asians. As well as greatly inflating the value of votes on the largely European roll, there was a further requirement in the 14 so-called "national" constituencies that successful candidates had to gain at least 10% of the African votes and 10% of the European ones. This complicated franchise, which also required voters to have a relatively high income, was used in elections of October 1962. In this, Kaunda's United National Independence Party gained only 14 seats with around 60% of the valid votes; the mainly European Federal party gained 16 seats with 17% of votes, and Nkumbula's Congress held the balance of power with 7 seats: only 37 of the 45 seats were filled, as in many of the "national" constituencies, no party gained 10% of both African and European votes.[95][96]

Although Congress had arranged before the election with the Federal party that their voters would vote for the other's candidates in some "national" constituencies, Nkumbula agreed to work in a coalition which had Kaunda as Prime Minister, and the two and their parties worked in reasonable harmony until a pre-independence election on 1964 where, with a much wider franchise, the United National Independence Party gained 55 of the 75 parliamentary seats. The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was formally dissolved on 31 December 1963, and the country became the independent Republic of Zambia on 24 October 1964, with Kaunda as President.[97][98]

Demographics

| Year | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natives | Europeans | Coloured | Asiatic | |

| 1911 | 826,000 | 1,497 | ||

| 1923 | 1,000,000 | 3,750 | ||

| 1925 | 1,140,642 | 4,624 | ||

| 1931 | 1,372,235 | 13,846 | ||

| 1932 | 1,382,705 | 10,553 | ||

| 1933 | 1,371,213 | 11,278 | ||

| 1935 | 1,366,425 | 10,000 | ||

| 1940 | 1,366,641 | 15,188 | ||

| 1943 | – | 18,745 | ||

| 1945 | 1,631,146 | 21,371 | ||

| 1946 | 1,634,980 | 21,919 | ||

| 1951 | 1,700,577 | 37,221 | 1,092 | 2,529 |

| 1954 | 2,040,000 | 60,000 | 1,400 | 4,600 |

| 1956 | 2,110,000 | 64,800 | 1,550 | 5,400 |

| 1960 | 2,340,000 | 76,000 | 2,000 | 8,000 |

| 1961 | 2,430,000 | 75,000 | 1,900 | 7,900 |

| 1963 | 3,460,000 | 74,000 | 2,300 | 8,900 |

Source: Whitaker's Almanack

Culture

Postage stamps

The British government issued postage stamps for Northern Rhodesia from 1925 to 1963. See Postage stamps and postal history of Northern Rhodesia for more details.

1964 Olympics

Zambia became the first country ever to change its name and flag between the opening and closing ceremonies of an Olympic Games. The country entered the 1964 Summer Olympics as Northern Rhodesia, and left in the closing ceremony as Zambia on 24 October, the day independence was formally declared.

See also

References

- Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1911 (although a protectorate, its official name was simply Northern Rhodesia)

- Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1911, S.R.O. 1911 No. 438, p. 85.

- Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia Order in Council, 1899, S.E.O. 1901 No. 567 (as amended, S.R.O. Rev. 1904, V.)

- North-Eastern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1900, S.R.O 1900 No. 89

- Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. P. 753

- Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1924, S.R.O. 1924 No. 324, S.RO. & S.I. Rev VIII, 154

- Zambia Independence Act, 1964 (c. 65)

- "Merriam-Webster online dictionary".

- J S Galbraith, (1974). Crown and Charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, University of California Press pp. 87, 202–3. ISBN 978-0-520-02693-3.

- J S Galbraith, (1974) Crown and charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, pp. 101–3.

- J S Galbraith, (1974). Crown and charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, pp. 211–5, 217–9.

- J S Galbraith, (1974). Crown and charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, p. 222.

- J S Galbraith, (1974). Crown and charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, pp. 103–4.

- NRZAM website: Alfred Sharpe's Travels in the Northern Province and Katanga. The Northern Rhodesia Journal. Vol III, No.3 (1957) pp. 210–219.

- David Gordon, (2000). Decentralized Despots or Contingent Chiefs: Comparing Colonial Chiefs in Northern Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo. KwaZulu-Natal History and African Studies Seminar, University of Natal, Durban.

- Government of Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), (1964). White Paper on British South Africa Company's claims to Mineral Royalties, pp. 1135, 1138.

- J S Galbraith, (1974). Crown and charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, pp. 222–3.

- Teresa Pinto Coelho, (2006). Lord Salisbury's 1890 Ultimatum to Portugal and Anglo-Portuguese Relations, pp. 6–7. http://www.mod-langs.ox.ac.uk/files/windsor/6_pintocoelho.pdf

- I Brownlie, (1979). African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia, Hurst & Co, pp. 706–13. ISBN 978-0-903983-87-7.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 86–7.

- I Brownlie, (1979). African Boundaries: A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopaedia, pp. 1306.

- J S Galbraith, (1974). Crown and charter: The early Years of the British South Africa Company, p. 223.

- P E N Tindall, (1967). A History of Central Africa, Praeger, p. 134.

- A Keppel-Jones (1983) Rhodes and Rhodesia: The White Conquest of Zimbabwe 1884–1902, McGill-Queen's Press, pp. 133–6. ISBN 978-0-7735-6103-8.

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1899). "Northern Rhodesia". In Wills, Walter H. (ed.). . Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. pp. 177–180.

- Gann, L.H. (1960). "History of Rhodesia and Nyasaland 1889–1953". Handbook to the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Federal Information Department. pp. 62, 74.

- G. D. Clough, (1924). The Constitutional Changes in Northern Rhodesia and Matters Incidental to the Transition, Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law, Third Series, Vol. 6, No. 4 pp. 279–80.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa : The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, p. 26.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 40–1, 45, 75–6.

- L H Gann, (1958). The Birth of a Plural Society: The Development of Northern Rhodesia under the British South Africa Company, 1894–1914, pp. 67, 74–5, 106–7.

- J G Pike, (1969). Malawi: A Political and Economic History, pp. 87, 90–2.

- J Lunn, (1992). The Political Economy of Primary Railway Construction in the Rhodesias, 1890–1911, The Journal of African History, Vol. 33, No. 2 pp. 239, 244.

- S Katzenellenbogen, (1974). Zambia and Rhodesia: Prisoners of the Past: A Note on the History of Railway Politics in Central Africa, African Affairs, Vol. 73, No. 290, pp. 63–4.

- S Katzenellenbogen, (1974). Zambia and Rhodesia: Prisoners of the Past: A Note on the History of Railway Politics in Central Africa, pp. 65–6.

- P Slinn, (1971). Commercial Concessions and Politics during the Colonial Period: The Role of the British South Africa Company in Northern Rhodesia 1890–1964, p. 369.

- Baxter, T.W.; E.E. Burke (1970). Guide to the Historical Manuscripts in the National Archives of Rhodesia. p. 67.

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. Doubleday, Page & company. pp. 2, Chapters 3 & 4. OCLC 407686.

- Juang, Richard M. (2008). Africa and the Americas: culture, politics, and history : a multidisciplinary encyclopedia, Volume 2 Transatlantic relations series. ABC-CLIO. p. 1157. ISBN 1-85109-441-5.

- S Cunningham, (1981). The Copper Industry in Zambia: Foreign Mining Companies in a Developing Country, pp. 57–8.

- R W Steel, (1957) The Copperbelt of Northern Rhodesia, pp. 83–4.

- A D Roberts. (1982). Notes towards a Financial History of Copper Mining in Northern Rhodesia, Canadian Journal of African Studies, Vol.16, No. 2, p. 348.

- S Cunningham, (1981). The Copper Industry in Zambia: Foreign Mining Companies in a Developing Country, Praeger, pp. 61, 68, 118.

- A D Roberts. (1982). Notes towards a Financial History of Copper Mining in Northern Rhodesia, pp. 348–9.

- S Cunningham, (1981). The Copper Industry in Zambia: Foreign Mining Companies in a Developing Country, pp. 53–5

- A D Roberts. (1982). Notes towards a Financial History of Copper Mining in Northern Rhodesia, pp. 349–50.

- S Cunningham, (1981). The Copper Industry in Zambia: Foreign Mining Companies in a Developing Country, pp. 57–8, 81.

- G. D. Clough, (1924). The Constitutional Changes in Northern Rhodesia and Matters Incidental to the Transition, p. 279.

- Davison, J.W. (1948). TheNorthern Rhodesian Legislative Council. London. pp. 23–24.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa : The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, pp. 109–10, 199.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa : The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, pp. 206, 208.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa : The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, p. 234.

- Clegg, Edward (1960). Race and Politics:Partnership in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 269–270.

- G. D. Clough, (1924). The Constitutional Changes in Northern Rhodesia and Matters Incidental to the Transition, pp. 279–80.

- "No. 35097". The London Gazette. 7 March 1941. p. 1364.

- "No. 37457". The London Gazette. 5 February 1946. p. 818.

- "No. 39391". The London Gazette. 23 November 1951. p. 6120.

- "No. 39417". The London Gazette. 25 December 1951. p. 6707.

- B. Malinowski, (1929). Report of the Commission on Closer Union of the Dependencies in Eastern and Central Africa, p. 317.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, Journal of the International African Institute Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 47–50.

- H. I Wetherell, (1979) Settler Expansionism in Central Africa: The Imperial Response of 1931 and Subsequent Implications, pp. 218, 225.

- B Raftopoulos and A S Mlambo, editors (2009) Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, p. 87.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, Journal of the International African Institute Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 199, 207.

- R I Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa : The Making of Malawi and Zambia, 1873–1964, Cambridge (Mass), Harvard University Press, pp. 37–8.

- Memorandum by the Colonial Secretary on Rhodesia, 19 April 1923. http://filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/small/cab-24-160-CP-201.pdf

- G. D. Clough, (1924). The Constitutional Changes in Northern Rhodesia and Matters Incidental to the Transition, Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law, Third Series, Vol. 6, No. 4 p. 281.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 56–60, 124–6, 136–9.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 45, 75–6.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 51, 165–6.

- Jenkins, E.E. (1937). Report of an Inquiry into the Causes of a Disturbance at Nkana on the 4th and 5 November 1937. Lusaka: Government Printer.

- Report of the Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Disturbances in the Copperbelt, Northern Rhodesia, July 1940. Lusaka: Government Printer.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 169, 171–3, 176.

- B Raftopoulos and A S Mlambo, editors (2009) Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, African Books Collective, p. 86. ISBN 978-1-77922-083-7.

- H. I Wetherell, (1979) Settler Expansionism in Central Africa: The Imperial Response of 1931 and Subsequent Implications, African Affairs, Vol. 78, No. 311, pp. 214–6, 225.

- H. I Wetherell, (1979) Settler Expansionism in Central Africa: The Imperial Response of 1931 and Subsequent Implications, pp. 216–7.

- C Leys and C Pratt, (1960) A New Deal in Central Africa, Praeger, pp.4–5.

- H. I Wetherell, (1979) Settler Expansionism in Central Africa: The Imperial Response of 1931 and Subsequent Implications, pp. 215–6.

- C Leys and C Pratt, (1960) A New Deal in Central Africa, p. 9.

- C Leys and C Pratt, (1960) A New Deal in Central Africa, pp. 9–10.

- M Chanock, (1977). Unconsummated union: Britain, Rhodesia and South Africa, 1900–45, Manchester University Press, p. 229. ISBN 978-0-7190-0634-0.

- M Chanock, (1977). Unconsummated union: Britain, Rhodesia and South Africa, 1900–45, p. 230.

- H. I Wetherell, (1979) Settler Expansionism in Central Africa: The Imperial Response of 1931 and Subsequent Implications, p. 223.

- B Raftopoulos and A S Mlambo, editors (2009) Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, pp. 87–8.

- E Windrich, (1975). The Rhodesian Problem: A Documentary Record 1923–1973, Routledge pp. 22–5. ISBN 978-0-7100-8080-6.

- A Okoth, (2006). A History of Africa: African Nationalism and the de-colonisation process, [1915–1995], Volume 2 East African Publishers, p. 101. ISBN 978-9966-25-358-3

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 226, 229–34, 269–70.

- A C Ross, (2009). Colonialism to Cabinet Crisis, African Books Collective, p.62. ISBN 99908-87-75-6

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 239, 249–51, 262–63.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 278, 285, 289–91.

- A Roberts, (1976).A History of Zambia, Africana Publishing Company, p. 220.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 297, 299–301.

- B Raftopoulos and A S Mlambo, editors (2009) Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, African Books Collective, p. 92.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 301, 307–10.

- R Blake, (1977). A History of Rhodesia, Knopf P.331. ISBN 0-394-48068-6.

- P Murray, (2005). British Documents on the End of Empire: Central Africa, Part I, Volume 9, pp.lxxiv-v, lxxx. ISBN 978-0-11-290586-8

- P Murray, (2005). British Documents on the End of Empire: Central Africa, pp.lxxxi-iv.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 311–12, 315.

- R. I. Rotberg, (1965). The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa, pp. 315–16.

- A Roberts, (1976).A History of Zambia, pp. 221–3.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Rhodesia". |

- The Great North Road, Northern Rhodesians worldwide

- Northern Rhodesia and Zambia, photographs and information from the 1950s and 1960s

- A Brief Guide to Northern Rhodesia

.svg.png)