Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula (Russian: Ко́льский полуо́стров, Kolsky poluostrov; from Kildin Sami: Куэлнэгк нёаррк, Kuelnegk njoarrk; Northern Sami: Guoládatnjárga; Finnish: Kuolan niemimaa; Norwegian: Kolahalvøya) is a peninsula in the far northwest of Russia. Constituting the bulk of the territory of Murmansk Oblast,[1][2] it lies almost completely inside the Arctic Circle and is bordered by the Barents Sea in the north and the White Sea in the east and southeast. The city of Murmansk is the most populous human settlement on the peninsula, with a population of over 300,000 as of the 2010 Census.[3]

| Кольский полуостров | |

|---|---|

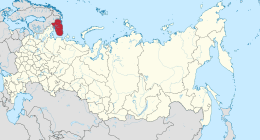

Kola Peninsula as a part of Murmansk Oblast | |

Location of Murmansk Oblast within Russia | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Far Northwest |

| Coordinates | 67°41′18″N 35°56′38″E |

| Adjacent bodies of water | |

| Area | 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi) |

| Length | 370 km (230 mi) |

| Width | 244 km (151.6 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,191 m (3,907 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Chasnachorr |

| Administration | |

Russia | |

| Oblast | Murmansk Oblast |

While the north of the peninsula was already settled in the 7th–5th millennium BCE, the rest of its territory remained uninhabited until the 3rd millennium BCE, when various peoples started to arrive from the south. However, by the 1st millennium CE only the Sami people remained. This changed in the 12th century, when Russian Pomors discovered the peninsula's game and fish riches. Soon after, the Pomors were followed by the tribute collectors from the Novgorod Republic, and the peninsula gradually became a part of the Novgorodian lands. No permanent settlements, however, were established by the Novgorodians until the 15th century.

The Soviet period saw a rapid increase of the population, although most of it remained confined to urbanized territories along the sea coast and the railroads. The Sami people were subject to forced collectivization, including forced relocation to Lovozero and other centralized settlements, and overall the peninsula was heavily industrialized and militarized, largely due to its strategic position and the discovery of the vast apatite deposits in the 1920s. As a result, the ecology of the peninsula suffered major ecological damage. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the economy went into decline. Its population fell from 1,150,000 in 1989 to 795,000 in 2010. The peninsula has recovered somewhat in the early 21st century, and is considered the most industrially developed and urbanized region in northern Russia.

Despite the peninsula's northerly location, its proximity to the Gulf Stream leads to unusually high temperatures in winter, but also results in high winds due to the temperature variations between land and the Barents Sea. Summers are rather chilly, with the average July temperature of only 11 °C (52 °F). The peninsula is covered by taiga in the south and tundra in the north, where permafrost limits the growth of the trees resulting in landscape dominated by shrubs and grasses. The peninsula supports a small variety of mammals, and its rivers are an important habitat for the Atlantic salmon. The Kandalaksha Nature Reserve, established to protect the population of common eider, is located in the Kandalaksha Gulf.

Geography

Location and overview

The peninsula is located in the far northwest of Russia, almost completely inside the Arctic Circle and is bordered by the Barents Sea in the north and the White Sea in the east and southeast.[4] Geologically, the peninsula occupies the northeastern edge of the Baltic Shield.[5] The western border of the peninsula stretches along the meridian from the Kola Bay through the valley of the Kola River, Lake Imandra, and the Niva River to the Kandalaksha Gulf,[5] although some sources push it all the way west to Russia's border with Finland.[6]

Under a more restrictive definition, the peninsula covers an area of about 100,000 square kilometers (39,000 sq mi).[5] The northern coast is steep and high, while the southern coast is flat.[5] The western part of the peninsula is covered by two mountain ranges: the Khibiny Mountains and the Lovozero Massif;[5] the former contains the highest point of the peninsula—Mount Chasnachorr, the height of which is 1,191 meters (3,907 ft).[4] The Keyvy drainage divide lies in the central part.[5] The mountainous reliefs of the Murman and Kandalaksha Coasts stretch from southeast to northwest, mirroring the peninsula's main orographic features.[4]

Administratively, the territory of the peninsula consists of Lovozersky and Tersky Districts, parts of Kandalakshsky and Kolsky Districts, as well as the territories subordinated to the cities and towns of Murmansk, Ostrovnoy, Severomorsk, Kirovsk, and parts of the territories subordinated to Apatity, Olenegorsk, and Polyarnye Zori.[7]

Natural resources

Because the last ice age removed the top sediment layer of the soil,[4] the Kola Peninsula is on the surface extremely rich in various ores and minerals, including apatites and nephelines; copper, nickel, and iron ores; mica; kyanites; ceramic materials,[8] as well as rare-earth elements and non-ferrous ores.[5] Deposits of construction materials such as granite, quartzite, and limestone are also abundant.[8] Diatomaceous earth deposits are common near lakes and are used to produce insulation.[8]

Climate

Proximity of the peninsula to the Gulf Stream leads to unusually high temperatures in winter, resulting in significant temperature variations between land and the Barents Sea and in fluctuating temperatures during high winds.[8] Cyclones are typical during the cold seasons, while the warm seasons are characterized by anticyclones.[8] Monsoon winds are common in most areas, with south and southwesterly winds prevailing in winter months and with somewhat more pronounced easterly winds in summer.[8] Strong storm winds blow for 80–120 days a year.[8] The waters of the Murman Coast remain warm enough to remain ice-free even in winter.[9]

Precipitation levels on the peninsula are rather high: 1,000 millimeters (39 in) in the mountains, 600–700 millimeters (24–28 in) on the Murman Coast, and 500–600 millimeters (20–24 in) in other areas.[8] The wettest months are August through October, while March and April are the driest.[8]

The average temperature in January is about −10 °C (14 °F), with lower temperatures typical in the central parts of the peninsula.[5] The average temperature in July is about +11 °C (52 °F).[5] Record lows reach −50 °C (−58 °F) in the central parts and −35 to −40 °C (−31 to −40 °F) on the coasts.[8] Record highs exceed +30 °C (86 °F) almost on all the territory of the peninsula.[8] First frosts occur as early as August and may last through May and even June.[8]

Most areas of the Kola Peninsula are subarctic climate (Köppen climate classification: Dfc). The nearby islands usually belong to tundra (Köppen climate classification: ET).

| Climate data for Murmansk (Climate ID:22113) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.2 (45.0) |

32.9 (91.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

0.6 (33.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −13.2 (8.2) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −39.4 (−38.9) |

−38.6 (−37.5) |

−32.6 (−26.7) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2 (28) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−21.2 (−6.2) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

−35 (−31) |

−39.4 (−38.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30 (1.2) |

22 (0.9) |

23 (0.9) |

24 (0.9) |

36 (1.4) |

53 (2.1) |

70 (2.8) |

61 (2.4) |

52 (2.0) |

51 (2.0) |

38 (1.5) |

34 (1.3) |

494 (19.4) |

| Source: Roshydromet[10] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Sosnovets Island (Climate ID:22355) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.4 (45.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −9.0 (15.8) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−0.2 (31.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −33.1 (−27.6) |

−33.2 (−27.8) |

−35.3 (−31.5) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−6 (21) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−6 (21) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−22.5 (−8.5) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−35.3 (−31.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19 (0.7) |

16 (0.6) |

20 (0.8) |

19 (0.7) |

33 (1.3) |

43 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

49 (1.9) |

42 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

27 (1.1) |

25 (1.0) |

383 (15.1) |

Flora and fauna

The peninsula is covered by taiga in the south and tundra in the north.[5] In the tundra, cold and windy conditions and permafrost limit the growth of the trees, resulting in a landscape dominated by grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs such as dwarf birch and cloudberry.[11] In northern coastal areas, stony and shrub lichens are common.[11] The taiga in the southern areas is composed mostly of pine trees and spruces.[5]

Reindeer herds visit the grasslands in summer.[11] Other animals include red and Arctic foxes, wolverines, moose,[11] otters, and lynx in the southern areas.[12] American minks, which were released near the Olenitsa River in 1935–1936, are now common throughout the peninsula and are commercially hunted.[12] Beavers, which became endangered by 1880, were re-introduced in 1934–1957.[12] All in all, thirty-two species of mammals and up to two hundred bird species inhabit the peninsula.[12]

Beluga whales are the only cetacean being common around the peninsula. Other dolphins, including Atlantic white-sided dolphins, white-beaked dolphins, and harbor porpoises,[13] as well as large whales, such as bowhead, humpback, blue, and finback, also visit the area.

The coasts of the Kandalaksha Gulf and the Barents Sea are important breeding grounds for bearded seals and ringed seals. The Barents Sea is one of the only places the rare Gray seals can be found.[14] Greenland seals, or harp seals, also can be seen from time to time.[15]

Twenty-nine species of fresh water fish are recognized on the territory of peninsula, including trout, stickleback, northern pike, and European perch.[12] The rivers are an important habitat for the Atlantic salmon, which return from Greenland and the Faroe Islands to spawn in fresh water. As a result of this, a recreational fishery has been developed, with a number of remote lodges and camps available to host sport-fishermen.[16] The Kandalaksha Nature Reserve, established in 1932 to protect the population of common eider,[17] is organized in thirteen clusters located in the Kandalaksha Gulf of the Kola Peninsula and along the coasts of the Barents Sea.[18]

Hydrology

The Kola Peninsula has many small but fast-moving rivers with rapids.[8] The most important of them are the Ponoy, the Varzuga, the Umba, the Teriberka, the Voronya, and the Yokanga.[5] Most rivers originate from lakes and swamps and collect their waters from melting snow.[8] The rivers become icebound during the winter, although the areas with strong rapids freeze later or not at all.[8]

Major lakes include Imandra, Umbozero, and Lovozero.[5] There are no lakes with an area smaller than 0.01 square kilometers (0.0039 sq mi).[8] Recreational fishery is developed in the region.[16]

Ecology

The Kola Peninsula as a whole suffered major ecological damage, mostly as a result of pollution from the military (particularly naval) production, industrial mining of apatite, and military nuclear waste.[11] About 137 active and 140 decommissioned or idle naval nuclear reactors, produced by the Soviet military, remain on the peninsula.[19] For thirty years, nuclear waste had been dumped into the sea by the Northern Fleet and Murmansk Shipping Company.[19] There is also evidence of contamination from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, with contaminants being found in the flesh of reindeer and other animals,[11] and from the 1972 and 1984 controlled nuclear explosions 21 kilometers (13 mi) northwest of Kirovsk.[20] Additionally, several nuclear weapons test ranges and radioactive waste storage facilities exist on the peninsula.[21][22]

The main industrial pollution source is Norilsk Nickel in Monchegorsk—the large smelters responsible for over 80% of the sulfur dioxide emissions and for nearly all nickel and copper emissions.[23] Since 1998, SO2 emissions in the area have dropped by almost 60%, from 88.3 thousand tonnes to 37.3 thousand tonnes in 2016, according to Norilsk Nickel.[24] Based on its new ‘Sulphur programme 2.0', Norilsk Nickel has set itself staged targets in cutting down sulphur dioxide emissions, which can have negative health and environmental effects. The ultimate aim is a 95% reduction (compared to 2015) in SO2 by 2030 for its Polar Division on the Taimyr peninsula, which includes its Nadezhda smelter and Copper plant, partly through a SO2 capture solution.[25] Other polluters of note include the thermal power stations in Apatity and Murmansk.[20]

History

Early history

The Rybachy Peninsula in the north of the Kola Peninsula was already settled in the 7th–5th millennium BCE.[26] In the 3rd–2nd millennium BCE, the peninsula was settled by the peoples who arrived there from the south (the territory of modern Karelia).[26] Bolshoy Oleny Island in the Kola Bay of the Barents Sea is the location of an important Bronze Age archaeological site where ancient DNA has been recovered.[27]

By the end of the 1st millennium CE, the peninsula was settled only by the Sami people, who did not have their own state, lived in clans ruled by elders,[28] and were engaged mostly in reindeer herding and fishing.[29] In the 12th century, Russian Pomors from the shores of the Onega Bay and in the lower reaches of the Northern Dvina discovered the peninsula and its game and fish riches.[28] The Pomors organized regular hunting and fishing visits and started barter trade with the Sami.[28] They also called the White Sea coast of the peninsula Tersky Coast (Те́рский бе́рег) or Terskaya Land (Те́рская земля́).[28]

By the end of the 12th century, the Pomors explored all northern coast of the peninsula and reached Finnmark (an area in the north of Norway), necessitating the Norwegians to support a naval guard in that area.[28] The name given by the Pomors to the northern coast was Murman—a distorted form of Norman meaning "Norwegian".[28]

Novgorodians

Pomors were soon followed by tribute collectors from the Novgorod Republic, and the Kola Peninsula gradually became a part of the Novgorodian lands.[28] A 1265 treaty of Yaroslav Yaroslavich with Novgorod mentions Tre Volost (волость Тре), which is later also mentioned in other documents dated as late as 1471.[28] In addition to Tre, Novgorodian documents of the 13th–15th centuries also mention Kolo Volost, which bordered Tre approximately along the line between Kildin Island and Turiy Headland of the Turiy Peninsula.[28] Kolo Volost lay to the west of that line, while Tre was situated to the east of it.[28]

By the 13th century, a need to formalize the border between the Novgorod Republic and the Scandinavian countries became evident.[30] The Novgorodians, along with the Karelians who came from the south, reached the coast of what now is Pechengsky District and the portion of the coast of Varangerfjord near the Jacob's River, which now is a part of Norway.[30] The Sami population was forced to pay tribute.[30] The Norwegians, however, were also attempting to take control of these lands, resulting in armed conflicts.[30] In 1251, a conflict between the Karelians, Novgorodians and the servants of the king of Norway led to the establishment of a Novgorodian mission in Norway.[30] Also in 1251, the first treaty with Norway was signed in Novgorod regarding the Sami lands and the system of tribute collections, making the Sami people pay tribute to both Novgorod and Norway.[30] By the terms of the treaty, Novgorodians could collect tribute from the Sami as far as Lyngen fjord in the west, while Norwegians could collect tribute on the territory of the whole Kola Peninsula except in the eastern part of Tersky Coast.[30] No state borders were established by the 1251 treaty.[30]

The treaty led to a short period of peace, but the armed conflicts resumed soon thereafter.[30] Chronicles document attacks by the Novgorodians and the Karelians on Finnmark and northern Norway as early as 1271, and continuing well into the 14th century.[30] The official border between the Novgorod lands and the lands of Sweden and Norway was established by the Treaty of Nöteborg on August 12, 1323.[30] The treaty primarily focused on the Karelian Isthmus border and the border north of Lake Ladoga.[30]

Another treaty dealing the matters of the northern borders was the Treaty of Novgorod signed with Norway in 1326, which ended the decades of the Norwegian-Novgorodian border skirmishes in Finnmark.[31] Per the terms of this treaty, Norway relinquished all claims to the Kola Peninsula.[31] However, the treaty did not address the situation with the Sami people paying tribute to both Norway and Novgorod, and the practice continued until 1602.[31] While the 1326 treaty did not define the border in detail, it confirmed the 1323 border demarcation, which remained more or less unchanged for the next six hundred years, until 1920.[31]

In the 15th century, Novgorodians started to establish permanent settlements on the peninsula.[31] Umba and Varzuga, the first documented permanent settlements of the Novgorodians, date back to 1466.[31] Over time, all coastal areas to the west of the Pyalitsa River had been settled, creating a territory where the population was mostly Novgorodian.[31] Administratively, this territory was divided into Varzuzhskaya and Umbskaya Volosts, which were governed by a posadnik from the area of the Northern Dvina.[31] The Novgorod Republic lost control of both of these volosts to the Grand Duchy of Moscow after the Battle of Shelon in 1471,[31] and the republic itself ceased to exist in 1478 when Ivan III took the city of Novgorod. All Novgorod territories, including those on the Kola Peninsula, became a part of the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[31]

The Novgorod Republic lost control of the peninsula to the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1471, but the Russian migration did not stop. Several new settlements were established during the 16th century, and the Sami and Pomor people were forced into serfdom. In the second half of the 16th century, the peninsula became a subject of dispute between the Tsardom of Russia and the Kingdom of Denmark–Norway, which resulted in the strengthening of the Russian position. By the end of the 19th century, the indigenous Sami population had been mostly forced north by the Russians as well as by newly arriving Izhma Komi and Kominized Nenets (so-called Yaran people), who migrated here to escape a reindeer disease epidemic in their home lands in the southeast of the White Sea. The original administrative and economic center of the area was Kola, situated at the estuary of the Kola River into the Kola Bay. However, in 1916, Romanov-na-Murmane (now Murmansk) was founded and quickly became the largest city and port on the peninsula.

Russian settlement

Russian migration to the peninsula continued into the 16th century, when new settlements such as Kandalaksha and Porya-Guba were established.[31] Kola was first mentioned in 1565.[31] In the end of the 15th century, the Pomors and the Sami people were forced into serfdom, mostly by the monasteries.[26] Monastery votchinas greatly expanded during the 17th century, but were abolished in 1764, when all of the Kola Peninsula peasants became state peasants.[26]

In the second half of the 16th century, King Frederick II of Denmark–Norway demanded that the Tsardom of Russia cede the peninsula.[31] Russia declined, and in order to organize adequate defenses established the position of a voyevoda.[32] The voyevoda sat in Kola, which became the administrative center of the region.[32] Prior to that, the administrative duties were performed by the tax collectors from Kandalaksha.[32] Newly established Kolsky Uyezd covered most of the territory of the peninsula (with the exception of Varzuzhskaya and Umbskaya Volosts, which were a part of Dvinsky Uyezd), as well as the northern part of Karelia all the way to Lendery.[32]

Despite the economic activity, permanent settlement of the peninsula did not intensify until the 1860s and even then it remained sporadic until 1917.[29] The population of Kola in 1880, for example, was only around 500 inhabitants living in 80 households, compared to 1,900 inhabitants in 300 households living there in 1582.[9] Transportation facilities were virtually non-existent and the communication with the rest of Russia irregular.[9] 1887 saw an influx of Izhma Komi and Nenets people who were migrating to the peninsula to escape a reindeer disease epidemic in their home lands and brought their large deer herds with them, resulting in increased competition for the grazing lands, a conflict between the Komi and the Sami, and in marginalization of the local Sami population.[33] By the end of the 19th century, the Sami population had mostly been forced north, with ethnic Russians settling in the south of the peninsula.[33]

In 1894, the peninsula was visited by the Russian Minister of Finance, who became convinced of the region's economic potential.[9] Consequently, in 1896 a telephone and a telegraph line were extended to Kola, improving the communication with the mainland.[9] A possibility of building a railway was also considered, but no action was taken at the time.[9] Also in 1896, Alexandrovsk (now Polyarny) was founded, and grew in size so rapidly that it was granted town status in 1899; Kolsky Uyezd was renamed Alexandrovsky on that occasion.[34]

During World War I, the still poorly developed peninsula suddenly found itself in a strategic position, as the communication between Russia and the Allies was cut and the ice-free harbors of the Murman Coast remained the only means of sending the war supplies to the Eastern Front.[9] In March 1915, the construction of the railroad was rushed, and the railroad was quickly opened in 1916, even though it was only partially completed and poorly built.[9] In 1916, Romanov-na-Murmane (modern Murmansk) was founded[34] as the terminal point of the new railroad;[9] the town quickly grew to become the largest one on the peninsula.

Soviet and modern periods

Soviet power was established on the territory of the peninsula on November 9 [O.S. October 26], 1917, but the territory was occupied by the forces of Russia's pre-war allies in March 1918–March 1920.[35] Alexandrovsky Uyezd was transformed into Murmansk Governorate by the Soviet government in June 1921.[36] On August 1, 1927, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee (VTsIK) issued two Resolutions: "On the Establishment of Leningrad Oblast" and "On the Borders and Composition of the Okrugs of Leningrad Oblast", according to which Murmansk Governorate was transformed into Murmansk Okrug (which was divided into six districts) and included into Leningrad Oblast.[36] This arrangement existed until May 28, 1938, when the okrug was separated from Leningrad Oblast, merged with Kandalakshsky District of the Karelian ASSR, and transformed into modern Murmansk Oblast.[37]

All in all, the Soviet period saw a significant increase in population (799,000 in 1970 vs. 15,000 in 1913), although most of the population remained concentrated in the urban localities along the railroads and the sea coast.[29] Most of the sparsely populated territories outside the urbanized areas were used for deer herding.[29] In 1920–1940, the town of Kirovsk and several work settlements were established on the peninsula.[35]

The Sami peoples were subject to forced collectivization, with more than half of their reindeer herds collectivized in 1928–1930.[33] In addition, the traditional Sami herding practices were phased out in favor of the more economically profitable Komi approach, which emphasized permanent settlements over free herding.[33] Since the Sami culture is strongly tied to the herding practices, this resulted in the Sami people gradually losing their language and traditional herding knowledge.[33] Most Sami were forced to settle in the village of Lovozero, which became the cultural center of the Sami people in Russia.[33] Those Sami resisting the collectivization were subject to forced labor or death.[33] Various forms of repression against the Sami continued until Stalin's death in 1953.[33] In the 1990s, 40% of the Sami lived in urbanized areas,[33] although some herd reindeer across much of the region.

The Sami were not the only people subject to repressions. Thousands of people were sent to Kola in the 1930s–1950s, and in 2007 over two thousand people—descendants of those forcibly sent here—still live on the peninsula.[38] A significant portion of the people deported to Kola were peasants from southern Russia subjected to dekulakization.[39] Prisoner labor was often used when building new factories[40] and for manning those which were operational: in 1940, for example, the whole Severonikel Metallurgy Mining Complex was turned over to the NKVD system.[41]

Demography

.jpg)

Until the 1800s, the Kola Peninsula was extremely sparsely populated, with only 5,200 inhabitants in 1858. In 1868 the Russian government created incentives for settlement and not only Russians but also Finns, Norwegians and Karelians moved to the peninsula. By the 1897 census 9,291 people were counted in the Kola uyezd; 63% Russian, 19% Sami, 11% Finnish and 3% Karelian.[42]

By 1913 about 13,000–15,000 people lived in the peninsula, mostly along the shores.[29][43] However, the discovery of the vast natural resource deposits and industrialization efforts led to an explosive population growth during the Soviet times.[43] By 1970, the population of the peninsula was around 799,000.[29] The trend reverted in the 1990s, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[40] The population of the whole Murmansk Oblast went down from 1,150,000 in 1989[44] to 890,000 in 2002[45] to 795,000 in 2010.[3]

As of the 2010 Census, the population consisted mostly of Russians (89.0%), Ukrainians (4.8%), and Belarusians (1.7%).[3] Other groups of note include Komi (~1,600 inhabitants), Sami (~1,600), and Karelians (~1,400).[3] The indigenous Sami people are mostly concentrated in Lovozersky District.[20]

Economy

Historical background

During the 15th–16th centuries, the main occupations of the Tersky Coast population were Atlantic salmon fishing, seal hunting, and the extraction of salt from the sea water.[26] The salt extraction in Kandalaksha and Kola was mostly carried out by the monasteries in Pechenga and Solovki, and for a long time remained the only "industry" on the peninsula.[46]

By the mid-16th century, Atlantic cod fishing developed on the Murman Coast in the north.[26] The 1560s saw a rapid growth of international trade, with the Russian merchants from different regions of the country arriving to the peninsula to trade with the merchants from Western Europe.[26] In 1585, however, the trade was moved to Archangel, although the settlement of Kola was still permitted to trade locally produced goods.[26]

During the 17th century, the salt extraction activities gradually went into decline as the locally produced salt was uncompetitive with cheap salt produced in the Kama River regions.[26] Extensive poaching also led to the significantly reduced outputs from pearl hunting.[26] However, commercial deer herding became more popular, although its share in the economy remained negligible until the 19th century.[26] By the end of the 17th century, the practice of seasonal fishing and hunting settlements in the north of the peninsula became very common.[29]

Peter the Great, recognizing the political and economical importance of the peninsula, promoted its industries and commerce; however, the region fell into neglect after St. Petersburg was founded in 1703 and most of the shipping trade shifted there.[9] In 1732, large deposits of silver in native form were discovered on Medvezhy Island in the Kandalaksha Gulf and copper, silver, and gold deposits were found in the lower reaches of the Ponoy River.[46] However, despite the efforts ongoing for the next two centuries, there was no commercial success.[46] At the end of the 18th century, the local population learned the practice of peat production from the Norwegians and started using peat for heating.[46] Timber cutting industry developed in the region at the end of the 19th century; mostly in Kovda and Umba.[26]

The Soviet era saw drastic industrialization and militarization of the peninsula. In 1925–1926, significant deposits of apatite were discovered in the Khibiny Mountains,[46] and the first apatite batch was shipped only a few years later, in 1929.[46] In 1930, sulfide deposits were discovered in the Moncha area; in 1932–1933 iron ore deposits were found near the upper streams of the Iona River; and in 1935, significant deposits of titanium ores were discovered in the area of modern Afrikanda.[46]

The collectivization efforts in the 1930s led to the concentration of the reindeer herds in kolkhozes (collective farms), which, in turn, were further consolidated into a few large-scale state farms in the late 1950s–early 1970s.[47] By the mid-1970s, the state farms were further consolidated into just two, based in Lovozero and Krasnoshchelye.[47] The consolidations were rationalized by the necessity to isolate the herders from the military installations, as well as by the need to flood some territories to construct hydroelectric plants.[47]

Fishing, being the traditional industry of the region, was always considered important, even though the volumes of production remained insignificant until the beginning of the 20th century.[48] In the 1920s–1930s, the Murmansk Trawl Fleet was created and the fishing infrastructure started to develop intensively.[48] By 1940, fishing accounted for 40% of the oblast's and for 80% of Murmansk's economy.[48]

During the Cold War, the peninsula served as the naval basing area for a large portion of the Soviet naval and air strategic forces, providing protection from and posing a threat to northern Norway.[49] Also the ELF-transmitter ZEVS of the Russian Navy is situated there.

Modern economy

After the economic slump of the 1990s, the economy of the oblast started to rebound during the first decade of the 2000s, although at a rate below the country's average.[20] Today the Kola Peninsula is the most industrially developed and urbanized region in northern Russia.[23] The major port of the peninsula is Murmansk, which serves as the administrative center of Murmansk Oblast[50] and does not freeze in winter.[5] Although the strategic importance of the Kola Peninsula has diminished since the Cold War,[49] the peninsula nevertheless still has the highest concentration of nuclear weapons, reactors, and facilities in Russia, with the number of nuclear reactors alone exceeding any other region of the world.[19]

Mining is the basis of the oblast's economy, and mining enterprises remain the principal employers in such monotowns as Apatity, Kirovsk, Zapolyarny, Nikel, and Monchegorsk.[51] The Kola Mining and Metallurgical Company, a division of Norilsk Nickel, conducts nickel-, copper-, and platinum-group-metals-mining operations on the peninsula.[52] Other large mining companies include OAO Apatit, which is the largest producer of phosphates in Europe; OAO Olcon, one of the leading producers of iron ore concentrates in Russia; and OAO Kovdorsky GOK, an ore-mining and processing enterprise.[51]

The fishing industry, although still operating significantly below the Soviet level of production,[20] remains profitable, supplying 20% of Russia's fish in 2006[48] and with the volume steadily growing in 2007–2010.[53] Murmansk is a key base for three fishing fleets, including Russia's largest, the Murmansk Trawl Fleet.[49] Fish breeding, especially of salmon and trout, is a growing industry.[49]

The energy sector is represented by the Kola Nuclear Power Plant near Polyarnye Zori, which produces about half of all energy, and a network of seventeen hydroelectric and two thermal power stations, generating the other half.[54] The energy surplus, accounting for about 20% of the total generated energy,[55] is transferred to the unified energy system of Russia, as well as exported to Norway and Finland via the NORDEL system.[54]

With the economy of the oblast being mostly export-oriented, transportation plays an important role and accounts for 11% of the Gross Regional Product.[56] On the Kola Peninsula, the transportation network includes ship transport, air transport, automotive transport, electrified public transport, and access to the railways mostly passing through the rest of Murmansk Oblast.[56] The city of Murmansk is an important port on the Northern Sea Route.[56] The largest airports are the Murmansk Airport, which handles international flights to Scandinavian countries, and the joint military-civilian Kirovsk-Apatity Airport[56] located 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) southeast of Apatity.

See also

References

- 2007 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. 2

- The area of the peninsula is 100,000 square kilometers (39,000 sq mi); vs. Murmansk Oblast's total area of 144,900 square kilometers (55,900 sq mi).

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- 1971 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. I

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Кольский полуостров (in Russian)

- See, for example, Bartold, p. 14

- 2007 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, pp. 6–7

- 1971 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. II.

- Field

- "Climate of Murmansk" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Kola Peninsula tundra". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on March 8, 2010.

- 1971 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. III

- ASCOBANS. 8th Advisory Committee Meeting. Report of the Nordic sub-Group on Research Priorities for ASCOBANS, Charlottenlund. February 14, 2001.

- "Seals". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- "Harp seals harping on in Greenland". oceanwide-expeditions.com. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- Richmond, p. 365

- Official website of the Kandalaksha Nature Reserve. Overview Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Tersky District, p. 16

- Avenhaus et al, p. 247

- Ministry of Economic Development of Murmansk Oblast. «Стратегия социально-экономического развития Мурманской области до 2020 года и на период до 2025 года» Archived August 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (Socioeconomic Development Strategy of Murmansk Oblast Until 2020 and for the Period Until 2025) (in Russian)

- "Nuclear waste removal starts in Andreeva Bay". The Barents Observer. May 18, 2017.

- "Russia's Last Cold War-Era Reactor Lifted Onshore in the Arctic". The Moscow Times. August 20, 2019.

- Rigina, p. 73.

- "Strategy". Nornickel. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- https://www.miningmagazine.com/sustainability/news/1376017/nornickel-to-clean-up-at-home

- 1971 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. V

- V.I. Khartanovich, V.G. Moiseev. Paleoanthropology and paleogenetics: MAE RAS collections research finding and further study potential Archived March 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Report to the International Scientific Conference "Archeology of the Arctic". YANAO Scientific Research Center of the Arctic. November 19–23, 2017. Salekhard.

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 16

- 1971 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. IV

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 17

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 18

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 19

- Robinson & Kassam, pp. 92–93

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 24

- 1971 Atlas of Murmansk Oblast, p. VI

- Administrative-Territorial Divisions of Murmansk Oblast, p. 28

- Decree of May 28, 1938

- RIA Novosti. A Monument to the Victims of Political Repressions Is Planned to Open in Murmansk by October 30 Archived April 17, 2013, at Archive.today. September 26, 2007 (in Russian)

- Kola Encyclopedia. Kola Krai in 1920–1939 Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- Richmond, p. 354

- Ivanova, p. 83

- Horváth, Casba. "Ethnogeographic metamorphosis of East Karelia during the 20th century CSABA HORVÁTH" (PDF). International Relations Quarterly. 1 (3). Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- Kozlov et al., p. 50

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- Natural Resources of the Kola Peninsula, pp. 14–16

- Costlow & Nelson, p. 125

- Kola Encyclopedia. Fishing Industry Archived April 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- GlobalSecurity.org. Murmansk Oblast

- Charter of Murmansk Oblast, Article 8.1.

- Kola Encyclopedia. Mining Industry Archived April 16, 2013, at Archive.today (in Russian).

- Official website of Norilsk Nickel. About Norilsk Nickel.

- Ministry of Economic Development of Murmansk Oblast. Fishing industry of Murmansk Oblast Archived August 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian).

- Kola Encyclopedia. Energy Sector Archived April 17, 2013, at Archive.today (in Russian).

- Kola Encyclopedia. Overview of the Economy Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian).

- Kola Encyclopedia. Transportation, Communications, Trade, Customs Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Russian).

Sources

- Министерство транспорта Российской Федерации. Федеральное агенство геодезии и картографии (2007). Мурманская область. Атлас. Санкт-Петербург: ФГУП "Геодезия".

- Главное управление геодезии и картографии при Совете Министров СССР. Научно-исследовательский географо-экономический институт Ленинградского государственного университета имени А. А. Жданова (1971). Атлас Мурманской области. Москва.

- Бартольд Е. Ф. (1935). По Карелии и Кольскому полуострову. ОГИЗ/Физкультура и туризм.

- Wm. O. Field, Jr. The Kola Peninsula. Gibraltar of the Western Arctic. The American Quarterly on the Soviet Union. July 1938. Vol. I, No. 2.

- Жиров Д. В., Пожиленко В. И., Белкина О. А. и др. (2006). Терский район (2-е, испр. и доп. ed.). Ника.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Simon Richmond (2006). Russia & Belarus. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781741042917. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- Rudolf Avenhaus; et al. (2002). Containing the Atom. Oxford: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739103876. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- Olga Rigina. GIS Analysis of Surface Water Chemistry Susceptibility and Response to Industrial Air Pollution in the Kola Peninsula, Northern Russia. Published in Biogeochemical Investigations at the Watershed, Landscape, and Regional Scales, Springer 1998.

- Архивный отдел Администрации Мурманской области. Государственный Архив Мурманской области. (1995). Административно-территориальное деление Мурманской области (1920–1993 гг.). Справочник. Мурманск: Мурманское издательско-полиграфическое предприятие "Север".

- Michael P. Robinson; Karim-Aly S. Kassam (1998). Sami potatoes: living with reindeer and perestroika. Calgary: Bayeux Arts. ISBN 9781896209111. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- Президиум Верховного Совета СССР. Указ от 28 мая 1938 г. «Об образовании Мурманской области». Опубликован: "Ведомости Верховного Совета СССР", №7, 1938. (Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Decree of May 28, 1938 On Establishing Murmansk Oblast. ).

- Galina Ivanova (2000). Donald J. Raleigh (ed.). Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Soviet Totalitarian System. M. E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 9780765639400. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- Mikhail Kozlov; et al. (2009). Impacts of Point Polluters on Terrestrial Biota: Comparative Analysis of 18 Contaminated Areas. Springer. ISBN 9789048124671. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- А. Е. Ферсман (1941). Полезные ископаемые Кольского полуострова. Москва, Ленинград: Издательство Академии наук СССР.

- Jane Costlow; Amy Nelson (2010). Other Animals: Beyond the Human in Russian Culture and History. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822960638. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- Мурманская областная Дума. Закон от 26 ноября 1997 г. «Устав Мурманской области», в ред. Закона №1448-01-ЗМО от 27 декабря 2011 г. «О внесении изменения в статью 58 Устава Мурманской области». Вступил в силу на двенадцатый день со дня официального опубликования в газете "Мурманский Вестник". Опубликован: "Мурманский Вестник", №235, стр. 6–7, 6 декабря 1997 г. (Murmansk Oblast Duma. Law of November 26, 1997 Charter of Murmansk Oblast, as amended by the Law #1448-01-ZMO of December 27, 2011 On Amending Article 58 of the Charter of Murmansk Oblast. Effective as of the day twelve days after the official publication in the Murmansky Vestnik newspaper.).

External links