Museum

A museum (/mjuːˈziːəm/ mew-ZEE-əm; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is an institution that cares for (conserves) a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make these items available for public viewing through exhibits that may be permanent or temporary.[1] The largest museums are located in major cities throughout the world, while thousands of local museums exist in smaller cities, towns, and rural areas. Museums have varying aims, ranging from serving researchers and specialists to serving the general public. The goal of serving researchers is increasingly shifting to serving the general public.

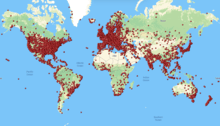

There are many types of museums, including art museums, natural history museums, science museums, war museums, and children's museums. Amongst the world's largest and most visited museums are the Louvre in Paris, the National Museum of China in Beijing, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the British Museum and National Gallery in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and Vatican Museums in Vatican City. According to the International Council of Museums, there are more than 55,000 museums in 202 countries.[2]

Etymology

The English "museum" comes from the Latin word, and is pluralized as "museums" (or rarely, "musea"). It is originally from the Ancient Greek Μουσεῖον (Mouseion), which denotes a place or temple dedicated to the Muses (the patron divinities in Greek mythology of the arts), and hence a building set apart for study and the arts,[3] especially the Musaeum (institute) for philosophy and research at Alexandria by Ptolemy I Soter about 280 BC.[4]

Purpose

The purpose of modern museums is to collect, preserve, interpret, and display objects of artistic, cultural, or scientific significance for the education of the public. From a visitor or community perspective, the purpose can also depend on one's point of view. A trip to a local history museum or large city art museum can be an entertaining and enlightening way to spend the day. To city leaders, a healthy museum community can be seen as a gauge of the economic health of a city, and a way to increase the sophistication of its inhabitants. To a museum professional, a museum might be seen as a way to educate the public about the museum's mission, such as civil rights or environmentalism. Museums are, above all, storehouses of knowledge. In 1829, James Smithson's bequest, that would fund the Smithsonian Institution, stated he wanted to establish an institution "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge."[5]

Museums of natural history in the late 19th century exemplified the Victorian desire for consumption and for order. Gathering all examples of each classification of a field of knowledge for research and for display was the purpose. As American colleges grew in the 19th century, they developed their own natural history collections for the use of their students. By the last quarter of the 19th century, the scientific research in the universities was shifting toward biological research on a cellular level, and cutting edge research moved from museums to university laboratories.[6] While many large museums, such as the Smithsonian Institution, are still respected as research centers, research is no longer a main purpose of most museums. While there is an ongoing debate about the purposes of interpretation of a museum's collection, there has been a consistent mission to protect and preserve artifacts for future generations. Much care, expertise, and expense is invested in preservation efforts to retard decomposition in aging documents, artifacts, artworks, and buildings. All museums display objects that are important to a culture. As historian Steven Conn writes, "To see the thing itself, with one's own eyes and in a public place, surrounded by other people having some version of the same experience can be enchanting."[7]

Museum purposes vary from institution to institution. Some favor education over conservation, or vice versa. For example, in the 1970s, the Canada Science and Technology Museum favored education over preservation of their objects. They displayed objects as well as their functions. One exhibit featured a historic printing press that a staff member used for visitors to create museum memorabilia.[8] Some seek to reach a wide audience, such as a national or state museum, while some museums have specific audiences, like the LDS Church History Museum or local history organizations. Generally speaking, museums collect objects of significance that comply with their mission statement for conservation and display. Although most museums do not allow physical contact with the associated artifacts, there are some that are interactive and encourage a more hands-on approach. In 2009, Hampton Court Palace, palace of Henry VIII, opened the council room to the general public to create an interactive environment for visitors. Rather than allowing visitors to handle 500-year-old objects, the museum created replicas, as well as replica costumes. The daily activities, historic clothing, and even temperature changes immerse the visitor in a slice of what Tudor life may have been.[9]

The statutes of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), adopted in 1970, define a museum as "a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment."[10] A proposed change to this definition, which would have museums actively engage with political and social issues, was postponed in 2020 after substantial opposition from ICOM members.[11]

Most-visited

This section lists the 20 most-visited museums in 2018 as compiled by AECOM and the Themed Entertainment Association's annual report on the world's most visited attractions.[12] The cities of London and Washington, D.C. contain more of the 20 most visited museums in the world than any others, with five museums and four museums, respectively.

History

Early history

Early museums began as the private collections of wealthy individuals, families or institutions of art and rare or curious natural objects and artifacts. These were often displayed in so-called wonder rooms or cabinets of curiosities. One of the oldest museums known is Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum, built by Princess Ennigaldi at the end of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The site dates from c. 530 BCE, and contained artifacts from earlier Mesopotamian civilizations. Notably, a clay drum label—written in three languages—was found at the site, referencing the history and discovery of a museum item.[16][17]

_04.jpg)

Public access to these museums was often possible for the "respectable", especially to private art collections, but at the whim of the owner and his staff. One way that elite men during this time period gained a higher social status in the world of elites was by becoming a collector of these curious objects and displaying them. Many of the items in these collections were new discoveries and these collectors or naturalists, since many of these people held interest in natural sciences, were eager to obtain them. By putting their collections in a museum and on display, they not only got to show their fantastic finds but they also used the museum as a way to sort and "manage the empirical explosion of materials that wider dissemination of ancient texts, increased travel, voyages of discovery, and more systematic forms of communication and exchange had produced."[18]

One of these naturalists and collectors was Ulisse Aldrovandi, whose collection policy of gathering as many objects and facts about them was "encyclopedic" in nature, reminiscent of that of Pliny, the Roman philosopher and naturalist.[19] The idea was to consume and collect as much knowledge as possible, to put everything they collected and everything they knew in these displays. In time, however, museum philosophy would change and the encyclopedic nature of information that was so enjoyed by Aldrovandi and his cohorts would be dismissed as well as "the museums that contained this knowledge." The 18th-century scholars of the Age of Enlightenment saw their ideas of the museum as superior and based their natural history museums on "organization and taxonomy" rather than displaying everything in any order after the style of Aldrovandi.[20]

While some of the oldest public museums in the world opened in Italy during the Renaissance, the majority of these significant museums in the world opened during the 18th century:

- the Capitoline Museums, the oldest public collection of art in the world, began in 1471 when Pope Sixtus IV donated a group of important ancient sculptures to the people of Rome.

- the Vatican Museums, the second oldest museum in the world, traces its origins to the public displayed sculptural collection begun in 1506 by Pope Julius II

- Ambras Castle (Schloss Ambras Innsbruck), Austria, is not the oldest art collection, but it is the earliest collection still to be found in that very building created especially for its museum purpose (1572–1583, Supplement 1589): Ambras Castle is the oldest museum in the world in several respects: the oldest pair of original building and initial collections; the oldest preserved collection in the history of museum according to a systematic concept; it houses – beside the Armouries – the only Renaissance Kunstkammer of its kind to have been preserved at its original location. Verifiably called a ‘museum’ as early as c.1580.

- the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London is the oldest museum in the United Kingdom. It opened to the public in 1660, though there had been paying privileged visitors to the armouries displays from 1592. Today the museum has three sites including its new headquarters in Leeds.[21]

- the Museum Kircherianum was opened around 1660 by the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher in the Roman College, exhibiting several of his automata and spectacles, such as his famous sunflower clock.

- Rumphius built a botanical museum in Ambon in 1662, making it the oldest recorded museum in Indonesia. Nothing remains of it except books written by himself, which are now in the library of the National Museum. Its successor was the Batavia Society of Art and Science, established on 24 April 1778. It built a museum and a library, played an important role in research, and collected much material on the natural history and culture of Indonesia.[22]

- the Amerbach Cabinet, originally a private collection, was bought by the university and city of Basel in 1661 and opened to the public in 1671.

- the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'archéologie in Besançon was established in 1694 after Jean-Baptiste Boisot, an abbot, gave his personal collection to the Benedictines of the city in order to create a museum open to the public two days every week.[23]

- the Kunstkamera in St. Petersburg was founded in 1717 in Kikin Hall and officially opened to the public in 1727 in the Old St. Petersburg Academy of Science Building

- the British Museum in London, was founded in 1753 and opened to the public in 1759.[24] Sir Hans Sloane's personal collection of curios provided the initial foundation for the British Museum's collection.[24]

- the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, This art collection was begun in the 15th century by Cosimo de' Medici, enlarged by his descendants, and in 1743 bequeathed by the last heir of the House of Medici "to the people of Tuscany and to all nations." The Uffizi Palace (built 1560-1581) was designed by the Renaissance painter and architect Giorgio Vasari. The top floors were converted to gallery space, open to visitors on request, and then opened to the public as a museum in 1769 by Grand Duke Peter Leopold.[25][26]

- the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation is the oldest in Latvia and the whole of the Baltics, and one of the oldest in Europe. It was founded and opened to public in 1773 by the Riga Town Council as Himsel Museum. The rich and diverse collections of the museum originated from an art and natural sciences collection of Nikolaus von Himsel (1729–1764), a Riga doctor. Today the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation collections number more than 500 000 items, systematised in about 80 collections.

- the Hermitage Museum was founded in 1764 by Catherine the Great and has been open to the public since 1852.

- the Museo del Prado in Madrid was founded in 1785 by Charles III of Spain, originally to house the Natural History Cabinet. Later, the building was converted into the new Royal Museum of Paintings and Sculptures, opened to the public in 1819, with the aim of showing the works of art belonging to the Spanish Crown. Nowadays, with the nearby Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and the Museo Reina Sofía, it forms the so-called Golden Triangle of Art.

- the Belvedere Palace of the Habsburg monarchs in Vienna opened with a collection of art in 1781.[27]

- the Teylers Museum in Haarlem (The Netherlands) established in 1778 and is the oldest Dutch museum.

- the Louvre Museum in Paris (France), also a former royal palace, opened to the public in 1793

- The Brukenthal National Museum, erected in the late 18th century in Sibiu, Transylvania, Romania, housed in the palace of Samuel von Brukenthal—who was Habsburg governor of Transylvania and who established its first collections around 1790. The collections were officially opened to the public in 1817, making it the oldest institution of its kind in Romania.

- The museum of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia dates to 1743,[28] making it the oldest museum in the United States.

- The Charleston Museum was established in 1773 thereby making it the first museum in the Southern United States. It did not open to the public until 1824.[29]

- Charles Willson Peale established America's first public museum in 1786 in Philadelphia's Independence Hall in 1786. It closed by the 1840s.[30]

- Indian Museum, Kolkata, established in 1814 is the oldest museum in India. It has a collection of 102,646 artifacts.[31]

Modern history

Modern museums first emerged in western Europe, then spread into other parts of the world.[32]

The first "public" museums were often accessible only by the middle and upper classes. It could be difficult to gain entrance. When the British Museum opened to the public in 1759, it was a concern that large crowds could damage the artifacts. Prospective visitors to the British Museum had to apply in writing for admission, and small groups were allowed into the galleries each day.[33] The British Museum became increasingly popular during the 19th century, amongst all age groups and social classes who visited the British Museum, especially on public holidays.[24]

The Ashmolean Museum, however, founded in 1677 from the personal collection of Elias Ashmole, was set up in the University of Oxford to be open to the public and is considered by some to be the first modern public museum.[34] The collection included that of Elias Ashmole which he had collected himself, including objects he had acquired from the gardeners, travellers and collectors John Tradescant the elder and his son of the same name. The collection included antique coins, books, engravings, geological specimens, and zoological specimens—one of which was the stuffed body of the last dodo ever seen in Europe; but by 1755 the stuffed dodo was so moth-eaten that it was destroyed, except for its head and one claw. The museum opened on 24 May 1683, with naturalist Robert Plot as the first keeper. The first building, which became known as the Old Ashmolean, is sometimes attributed to Sir Christopher Wren or Thomas Wood.[35]

_(6998203541).jpg)

In France, the first public museum was the Louvre Museum in Paris,[36] opened in 1793 during the French Revolution, which enabled for the first time free access to the former French royal collections for people of all stations and status. The fabulous art treasures collected by the French monarchy over centuries were accessible to the public three days each "décade" (the 10-day unit which had replaced the week in the French Republican Calendar). The Conservatoire du muséum national des Arts (National Museum of Arts's Conservatory) was charged with organizing the Louvre as a national public museum and the centerpiece of a planned national museum system. As Napoléon I conquered the great cities of Europe, confiscating art objects as he went, the collections grew and the organizational task became more and more complicated. After Napoleon was defeated in 1815, many of the treasures he had amassed were gradually returned to their owners (and many were not). His plan was never fully realized, but his concept of a museum as an agent of nationalistic fervor had a profound influence throughout Europe.

Chinese and Japanese visitors to Europe were fascinated by the museums they saw there, but had cultural difficulties in grasping their purpose and finding an equivalent Chinese or Japanese term for them. Chinese visitors in the early 19th century named these museums based on what they contained, so defined them as "bone amassing buildings" or "courtyards of treasures" or "painting pavilions" or "curio stores" or "halls of military feats" or "gardens of everything". Japan first encountered Western museum institutions when it participated in Europe's World's Fairs in the 1860s. The British Museum was described by one of their delegates as a 'hakubutsukan', a 'house of extensive things' – this would eventually become accepted as the equivalent word for 'museum' in Japan and China.[37]

American museums eventually joined European museums as the world's leading centers for the production of new knowledge in their fields of interest. A period of intense museum building, in both an intellectual and physical sense was realized in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (this is often called "The Museum Period" or "The Museum Age"). While many American museums, both natural history museums and art museums alike, were founded with the intention of focusing on the scientific discoveries and artistic developments in North America, many moved to emulate their European counterparts in certain ways (including the development of Classical collections from ancient Egypt, Greece, Mesopotamia, and Rome). Drawing on Michel Foucault's concept of liberal government, Tony Bennett has suggested the development of more modern 19th-century museums was part of new strategies by Western governments to produce a citizenry that, rather than be directed by coercive or external forces, monitored and regulated its own conduct. To incorporate the masses in this strategy, the private space of museums that previously had been restricted and socially exclusive were made public. As such, objects and artifacts, particularly those related to high culture, became instruments for these "new tasks of social management."[39] Universities became the primary centers for innovative research in the United States well before the start of World War II. Nevertheless, museums to this day contribute new knowledge to their fields and continue to build collections that are useful for both research and display.

The late twentieth century witnessed intense debate concerning the repatriation of religious, ethnic, and cultural artifacts housed in museum collections. In the United States, several Native American tribes and advocacy groups have lobbied extensively for the repatriation of sacred objects and the reburial of human remains.[40] In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), which required federal agencies and federally funded institutions to repatriate Native American "cultural items" to culturally affiliate tribes and groups.[41] Similarly, many European museum collections often contain objects and cultural artifacts acquired through imperialism and colonization. Some historians and scholars have criticized the British Museum for its possession of rare antiquities from Egypt, Greece, and the Middle East.[42]

Management

The roles associated with the management of a museum largely depend on the size of the institution, but every museum has a hierarchy of governance with a Board of Trustees serving at the top. The Director is next in command and works with the Board to establish and fulfill the museum's mission statement and to ensure that the museum is accountable to the public.[43] Together, the Board and the Director establish a system of governance that is guided by policies that set standards for the institution. Documents that set these standards include an institutional or strategic plan, institutional code of ethics, bylaws, and collections policy. The American Alliance of Museums (AAM) has also formulated a series of standards and best practices that help guide the management of museums.

- Board of Trustees – The board governs the museum and is responsible for ensuring the museum is financially and ethically sound. They set standards and policies for the museum. Board members are often involved in fundraising aspects of the museum and represent the institution.

- Director- The director is the face of the museum to the professional and public community. They communicate closely with the board to guide and govern the museum. They work with the staff to ensure the museum runs smoothly.

According to museum professionals Hugh H. Genoways and Lynne M. Ireland, "Administration of the organization requires skill in conflict management, interpersonal relations, budget management and monitoring, and staff supervision and evaluation. Managers must also set legal and ethical standards and maintain involvement in the museum profession."[44]

Various positions within the museum carry out the policies established by the Board and the Director. All museum employees should work together toward the museum's institutional goal. Here is a list of positions commonly found at museums:

- Curator – Curators are the intellectual drivers behind exhibits. They research the museum's collection and topic of focus, develop exhibition themes, and publish their research aimed at either a public or academic audience. Larger museums have curators in a variety of areas. For example, The Henry Ford has a Curator of Transportation, a Curator of Public Life, a Curator of Decorative Arts, etc.

- Collections Management – Collections managers are primarily responsible for the hands-on care, movement, and storage of objects. They are responsible for the accessibility of collections and collections policy.

- Registrar – Registrars are the primary record keepers of the collection. They insure that objects are properly accessioned, documented, insured, and, when appropriate, loaned. Ethical and legal issues related to the collection are dealt with by registrars. Along with collections managers, they uphold the museum's collections policy.

- Educator – Museum educators are responsible for educating museum audiences. Their duties can include designing tours and public programs for children and adults, teacher training, developing classroom and continuing education resources, community outreach, and volunteer management.[45] Educators not only work with the public, but also collaborate with other museum staff on exhibition and program development to ensure that exhibits are audience-friendly.

- Exhibit Designer – Exhibit designers are in charge of the layout and physical installation of exhibits. They create a conceptual design and then bring it to fruition in the physical space.

- Conservator – Conservators focus on object restoration. More than preserving the object in its present state, they seek to stabilize and repair artifacts to the condition of an earlier era.[46]

Other positions commonly found at museums include: building operator, public programming staff, photographer, librarian, archivist, groundskeeper, volunteer coordinator, preparator, security staff, development officer, membership officer, business officer, gift shop manager, public relations staff, and graphic designer.

At smaller museums, staff members often fulfill multiple roles. Some of these positions are excluded entirely or may be carried out by a contractor when necessary.

Exhibition histories

An exhibition history is a listing of exhibitions for an institution, artist, or a work of art. Exhibition histories generally include the name of the host institution, the title of the exhibition and the opening and closing dates of the exhibition.

The following is a list of major institutions that have complete or substantial exhibition histories that are available online.

- Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (1961–present)[47]

- British Museum (1838–2012)[48]

- Brooklyn Museum (1846–present)[49]

- Art Institute of Chicago (1883–present)[50]

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1988–present)[51]

- Cleveland Museum of Art (1916–present)[52]

- Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (1948–present)[53]

- Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC (1901–present)[54]

- Dahesh Museum of Art, New York (1995–2007)[55]

- Dallas Museum of Art (1903–present)[56]

- The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1984–present)[57]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York (1929–present)[58]

- National Gallery of Art, Washington DC (1941–present)[59]

- Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario (1912–present)[60]

Protection

The cultural property stored in museums is threatened in many countries by natural disaster, war, terrorist attacks or other emergencies. To this end, an internationally important aspect is a strong bundling of existing resources and the networking of existing specialist competencies in order to prevent any loss or damage to cultural property or to keep damage as low as possible. International partner for museums is UNESCO and Blue Shield International in accordance with the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property from 1954 and its 2nd Protocol from 1999. For legal reasons, there are many international collaborations between museums, and the local Blue Shield organizations.[61][62]

Blue Shield has conducted extensive missions to protect museums and cultural assets in armed conflict, such as 2011 in Egypt and Libya, 2013 in Syria and 2014 in Mali and Iraq. During these operations, the looting of the collection is to be prevented in particular.[63]

Planning

The design of museums has evolved throughout history. However, museum planning involves planning the actual mission of the museum along with planning the space that the collection of the museum will be housed in. Intentional museum planning has its beginnings with the museum founder and librarian John Cotton Dana. Dana detailed the process of founding the Newark Museum in a series of books in the early 20th century so that other museum founders could plan their museums. Dana suggested that potential founders of museums should form a committee first, and reach out to the community for input as to what the museum should supply or do for the community.[64] According to Dana, museums should be planned according to community's needs:

"The new museum ... does not build on an educational superstition. It examines its community's life first, and then straightway bends its energies to supplying some the material which that community needs, and to making that material's presence widely known, and to presenting it in such a way as to secure it for the maximum of use and the maximum efficiency of that use."[65]

The way that museums are planned and designed vary according to what collections they house, but overall, they adhere to planning a space that is easily accessed by the public and easily displays the chosen artifacts. These elements of planning have their roots with John Cotton Dana, who was perturbed at the historical placement of museums outside of cities, and in areas that were not easily accessed by the public, in gloomy European style buildings.[66]

Questions of accessibility continue to the present day. Many museums strive to make their buildings, programming, ideas, and collections more publicly accessible than in the past. Not every museum is participating in this trend, but that seems to be the trajectory of museums in the twenty-first century with its emphasis on inclusiveness. One pioneering way museums are attempting to make their collections more accessible is with open storage. Most of a museum's collection is typically locked away in a secure location to be preserved, but the result is most people never get to see the vast majority of collections. The Brooklyn Museum's Luce Center for American Art practices this open storage where the public can view items not on display, albeit with minimal interpretation. The practice of open storage is all part of an ongoing debate in the museum field of the role objects play and how accessible they should be.[67]

In terms of modern museums, interpretive museums, as opposed to art museums, have missions reflecting curatorial guidance through the subject matter which now include content in the form of images, audio and visual effects, and interactive exhibits. Museum creation begins with a museum plan, created through a museum planning process. The process involves identifying the museum's vision and the resources, organization and experiences needed to realize this vision. A feasibility study, analysis of comparable facilities, and an interpretive plan are all developed as part of the museum planning process.

Some museum experiences have very few or no artifacts and do not necessarily call themselves museums, and their mission reflects this; the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, being notable examples where there are few artifacts, but strong, memorable stories are told or information is interpreted. In contrast, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. uses many artifacts in their memorable exhibitions.

Financial uses

In recent years, some cities have turned to museums as an avenue for economic development or rejuvenation. This is particularly true in the case of postindustrial cities.[68] Examples of museums fulfilling these economic roles exist around the world. For example, the spectacular Guggenheim Bilbao was built in Bilbao, Spain in a move by the Basque regional government to revitalize the dilapidated old port area of that city. The Basque government agreed to pay $100 million for the construction of the museum, a price tag that caused many Bilbaoans to protest against the project.[69] Nonetheless, the gamble has appeared to pay off financially for the city, with over 1.1 million people visiting the museum in 2015. Key to this is the large demographic of foreign visitors to the museum, with 63% of the visitors residing outside of Spain and thus feeding foreign investment straight into Bilbao.[70] A similar project to that undertaken in Bilbao was also built on the disused shipyards of Belfast, Northern Ireland. Titanic Belfast was built for the same price as the Guggenheim Bilbao (and which was incidentally built by the same architect, Frank Gehry) in time for the 100th anniversary of the Belfast-built ship's maiden voyage in 2012. Initially expecting modest visitor numbers of 425,000 annually, first year visitor numbers reached over 800,000, with almost 60% coming from outside Northern Ireland.[71] In the United States, similar projects include the 81, 000 square foot Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia and The Broad Museum in Los Angeles.

Museums being used as a cultural economic driver by city and local governments has proven to be controversial among museum activists and local populations alike. Public protests have occurred in numerous cities which have tried to employ museums in this way. While most subside if a museum is successful, as happened in Bilbao, others continue especially if a museum struggles to attract visitors. The Taubman Museum of Art is an example of a museum which cost a lot (eventually $66 million) but attained little success, and continues to have a low endowment for its size.[72] Some museum activists also see this method of museum use as a deeply flawed model for such institutions. Steven Conn, one such museum proponent, believes that "to ask museums to solve our political and economic problems is to set them up for inevitable failure and to set us (the visitor) up for inevitable disappointment."[68]

Funding

Museums are facing funding shortages. Funding for museums comes from four major categories, and as of 2009 the breakdown for the United States is as follows: Government support (at all levels) 24.4%, private (charitable) giving 36.5%, earned income 27.6%, and investment income 11.5%.[73] Government funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the largest museum funder in the United States, decreased by 19.586 million between 2011 and 2015, adjusted for inflation.[74][75] The average spent per visitor in an art museum in 2016 was $8 between admissions, store and restaurant, where the average expense per visitor was $55.[76] Corporations, which fall into the private giving category, can be a good source of funding to make up the funding gap. The amount corporations currently give to museums accounts for just 5% of total funding.[77] Corporate giving to the arts, however, was set to increase by 3.3% in 2017.[78]

Exhibition design

Most mid-size and large museums employ exhibit design staff for graphic and environmental design projects, including exhibitions. In addition to traditional 2-D and 3-D designers and architects, these staff departments may include audio-visual specialists, software designers, audience research, evaluation specialists, writers, editors, and preparators or art handlers. These staff specialists may also be charged with supervising contract design or production services. The exhibit design process builds on the interpretive plan for an exhibit, determining the most effective, engaging and appropriate methods of communicating a message or telling a story. The process will often mirror the architectural process or schedule, moving from conceptual plan, through schematic design, design development, contract document, fabrication, and installation. Museums of all sizes may also contract the outside services of exhibit fabrication businesses.[79]

Exhibition design has as multitude of strategies, theories, and methods but two that embody much of the theory and dialogue surrounding exhibition design are the metonymy technique and the use of authentic artifacts to provide the historical narrative. Metonymy, or "the substitution of the name of an attribute or adjunct for that of the thing meant,"[80] is a technique used by many museums but few as heavily and as influentially as Holocaust museums.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., for example, employs this technique in its shoe exhibition. Simply a pile of decaying leather shoes piled against a bare, gray concrete wall the exhibit relies heavily on the emotional, sensory response the viewer will naturally through this use metonymic technique. This exhibition design intentionally signifies metonymically the nameless and victims themselves. This metaphysical link to the victims through the deteriorating and aged shoes stands as a surviving vestige of the individual victim. This technique, employed properly, can be a very powerful one as it plays off the real life experiences of the viewer while evoking the equally unique memory of the victim. Metonymy, however, Jennifer Hansen-Glucklich argues, is not without its own problems. Hansen-Glucklich explains, "...when victims' possessions are collected according to type and displayed en masse they stand metonymically for the victims themselves ... Such a use of metonymy contributes to the dehumanization of the victims as they are reduced to a heap of indistinguishable objects and their individuality subsumed by an aesthetic of anonymity and excess."[81]

While a powerful technique, Hansen-Glucklick points out that when used en masse the metonym suffers as the memory and suffering of the individual is lost in the chorus of the whole. While at times juxtaposed, the alternative technique of the use of authentic objects is seen the same exhibit mentioned above. The use of authentic artifacts is employed by most, if not all, museums but the degree to which and the intention can vary greatly. The basic idea behind exhibiting authentic artifacts is to provide not only legitimacy to the exhibit's historical narrative but, at times, to help create the narrative as well. The theory behind this technique is to exhibit artifacts in a neutral manner to orchestrate and narrate the historic narrative through, ideally, the provenance of the artifacts themselves.

While albeit necessary to some degree in any museum repertoire, the use of authentic artifacts can not only be misleading but as equally problematic as the aforementioned metonymic technique. Hansen-Glucklick explains, "The danger of such a strategy lies in the fact that by claiming to offer the remnants of the past to the spectator, the museum creates the illusion of standing before a complete picture. The suggestion is that if enough details and fragments are collected and displayed, a coherent and total truth concerning the past will emerge, visible and comprehensible. The museum attempts, in other words, to archive the unachievable."[81] While any exhibit benefits from the legitimacy given by authentic objects or artifacts, the temptation must be protected against in order to avoid relying solely on the artifacts themselves. A well designed exhibition should employ objects and artifacts as a foundation to the narrative but not as a crutch; a lesson any conscientious curator would be well to keep in mind.[82]

Some museum scholars have even begun to question whether museums truly need artifacts at all. Historian Steven Conn provocatively asks this question, suggesting that there are fewer objects in all museums now, as they have been progressively replaced by interactive technology.[83] As educational programming has grown in museums, mass collections of objects have receded in importance. This is not necessarily a negative development. Dorothy Canfield Fisher observed that the reduction in objects has pushed museums to grow from institutions that artlessly showcased their many artifacts (in the style of early cabinets of curiosity) to instead "thinning out" the objects presented "for a general view of any given subject or period, and to put the rest away in archive-storage-rooms, where they could be consulted by students, the only people who really needed to see them."[84] This phenomenon of disappearing objects is especially present in science museums like the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, which have a high visitorship of school-aged children who may benefit more from hands-on interactive technology than reading a label beside an artifact.[85]

Types

Museums can vary based on size, from large institutions covering many of the categories below, to very small institutions focusing on a specific subjects, such as a specific location, a notable person, or a given period of time. Museums can also be categorized into major groups by the type of collections they display, to include: fine arts, applied arts, craft, archaeology, anthropology and ethnology, biography, history, cultural history, science, technology, children's museums, natural history, botanical and zoological gardens. Within these categories, many museums specialize further, e.g. museums of modern art, folk art, local history, military history, aviation history, philately, agriculture, or geology. Another type of museum is an encyclopedic museum. Commonly referred to as a universal museum, encyclopedic museums have collections representative of the world and typically include art, science, history, and cultural history. The size of a museum's collection typically determines the museum's size, whereas its collection reflects the type of museum it is. Many museums normally display a "permanent collection" of important selected objects in its area of specialization, and may periodically display "special collections" on a temporary basis.

It may sometimes be useful to distinguish between diachronic and synchronic museums. According to University of Florida's Professor Eric Kilgerman, "While a museum in which a particular narrative unfolds within its halls is diachronic, those museums that limit their space to a single experience are called synchronic."[86]

Agricultural

Agricultural museums are dedicated to preserving agricultural history and heritage.[87] They aim to educate the public on the subject of agricultural history, their legacy and impact on society.[88] To accomplish this, they specialize in the display and interpretation of artifacts related to agriculture, often of a specific time period or in a specific region, as in the case of the Sarka museum in Loimaa, Finland. They may also display memorabilia related to farmers or businesspeople who impacted society via agriculture (e.g., larger size of the land cultivated as compared to other similar farms) or agricultural advances, such as new technology implementation, as in the case of Museo Hacienda Buena Vista.

Architectural

Architectural museums are institutions dedicated to educating visitors about architecture and a variety of related fields, often including urban design, landscape design, interior decoration, engineering, and historic preservation. Additionally, museums of art or history sometimes dedicate a portion of the museum or a permanent exhibit to a particular facet or era of architecture and design, though this does not technically constitute a proper museum of architecture.

The International Confederation of Architectural Museums (ICAM) is the principal worldwide organisation for architectural museums. Members consist of almost all large institutions specializing in this field and also those offering permanent exhibitions or dedicated galleries.

Architecture museums are in fact a less common type in the United States, due partly to the difficulty of curating a collection which could adequately represent or embody the large scale subject matter.

The National Building Museum in Washington D.C., a privately run institution created by a mandate of Congress in 1980, is the nation's most prominent public museum of architecture. In addition to its architectural exhibits and collections, the museum seeks to educate the public about engineering and design. The NBM is a unique museum in that the building in which it is housed—the historic Pension Building built 1882–87—is itself a sort of curated collection piece which teaches about architecture. Another large scale museum of architecture is the Chicago Athenaeum, an international Museum of Architecture and Design, founded in 1988. The Athenaeum differs from the National Building Museum not only in its global scope—it has offices in Italy, Greece, Germany, and Ireland—but also in its broader topical scope, which encompasses smaller modern appliances and graphic design.

A very different and much smaller example of an American architectural museum is the Schifferstadt Architectural Museum in Frederick, Maryland. Similar to the National Building Museum, the building of the Schifferstadt is a historic structure, built in 1758, and therefore also an embodiment of historic preservation and restoration. In addition to instructing the public about its eighteenth-century German-American style architecture, the Schifferstadt also interprets the broader contextual history of its origins, including topics such as the French and Indian War and the arrival of the region's earliest German American immigrants.

Museums of architecture are devoted primarily to disseminating knowledge about architecture, but there is considerable room for expanding into other related genres such as design, city planning, landscape, infrastructure, and even the traditional study of history or art, which can provide useful context for any architectural exhibit.

The American Society of Landscape Architects has professional awards given out every year to architectural museums and art displays. A few of the award-winning projects are: Perez Art Museum Miami: Resiliency by Design,[89] Teardrop Park: General Design Category,[90] and Mesa Arts Center: General Design Honor Award[91]

Archaeological

Archaeology museums specialize in the display of archaeological artifacts. Many are in the open air, such as the Agora of Athens and the Roman Forum. Others display artifacts found in archaeological sites inside buildings. Some, such as the Western Australian Museum, exhibit maritime archaeological materials. These appear in its Shipwreck Galleries, a wing of the Maritime Museum. This Museum has also developed a 'museum-without-walls' through a series of underwater wreck trails.

_Tappeh_Sarab%2C_Kermanshah_ca._7000-6100_BCE_Neolithic_period%2C_National_Museum_of_Iran.jpg)

Art

An art museum, also known as an art gallery, is a space for the exhibition of art, usually in the form of art objects from the visual arts, primarily paintings, illustrations, and sculptures. Collections of drawings and old master prints are often not displayed on the walls, but kept in a print room. There may be collections of applied art, including ceramics, metalwork, furniture, artist's books, and other types of objects. Video art is often screened.

The first publicly owned museum in Europe was the Amerbach-Cabinet in Basel, originally a private collection sold to the city in 1661 and public since 1671 (now Kunstmuseum Basel).[92] The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford opened on 24 May 1683 as the world's first university art museum. Its first building was built in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities Elias Ashmole gave Oxford University in 1677. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence was initially conceived as offices for the Florentine civil service (hence the name), but evolved into a display place for many of the paintings and sculpture collected by the Medici family or commissioned by them. After the house of Medici was extinguished, the art treasures remained in Florence, forming one of the first modern museums. The gallery had been open to visitors by request since the sixteenth century, and in 1765 it was officially opened to the public. Another early public museum was the British Museum in London, which opened to the public in 1759.[24] It was a "universal museum" with very varied collections covering art, applied art, archaeology, anthropology, history, and science, and what is now the British Library. The science collections, library, paintings, and modern sculptures have since been found separate homes, leaving history, archaeology, non-European and pre-Renaissance art, and prints and drawings. Underwater museum is another type of art museum where the Artificial reef are placed to promote marine life. Cancun Underwater Museum, or the Subaquatic Sculpture Museum, in Mexico is the largest underwater museum in the world. There are now about 500 images in the underwater museum. The last eleven images were added in September 2013.[93]

The specialised art museum is considered a fairly modern invention, the first being the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg which was established in 1764.

The Louvre in Paris was established in 1793, soon after the French Revolution when the royal treasures were declared for the people.[94] The Czartoryski Museum in Kraków was established in 1796 by Princess Izabela Czartoryska.[95] This showed the beginnings of removing art collections from the private domain of aristocracy and the wealthy into the public sphere, where they were seen as sites for educating the masses in taste and cultural refinement.

Biographical

Biographical museums are dedicated to items relating to the life of a single person or group of people, and may also display the items collected by their subjects during their lifetimes. Some biographical museums are located in a house or other site associated with the lives of their subjects (e.g. Sagamore Hill which contains the Theodore Roosevelt Museum or The Keats-Shelley Memorial House in the Piazza di Spagna, Rome). Some homes of famous people house famous collections in the sphere of the owner's expertise or interests in addition to collections of their biographical material; one such example is Apsley House, London, home of the Duke of Wellington, which, in addition to biographical memorabilia of the Duke's life, also houses his collection world-famous paintings. Other biographical museums, such as many of the American presidential libraries, are housed in specially constructed buildings.

Automobile

There are one hundred and seven automobile museums in the United States, one in Canada, and one in the Republic of Georgia according to the National Association of Automobile Museums.[96] Automobile Museums are for car fans, collectors, enthusiasts, and for families. “They speak to the imagination,” says Ken Gross, a former museum director who now curates auto exhibits at the fine arts museum.[97] As time goes by, more and more museums dedicated to classic cars of yesteryear are opening. Many of the old classics come to life once the original owners pass away. Some are not-for-profit while others are run as a private business.

Children's

Children's museums are institutions that provide exhibits and programs to stimulate informal learning experiences for children. In contrast with traditional museums that typically have a hands-off policy regarding exhibits, children's museums feature interactive exhibits that are designed to be manipulated by children. The theory behind such exhibits is that activity can be as educational as instruction, especially in early childhood. Most children's museums are nonprofit organizations, and many are run by volunteers or by very small professional staffs.[99]

The Brooklyn Children's Museum was established in 1899 by the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. It is often regarded as the first children's museum in the United States.[100] The idea behind the Brooklyn Children's Museum implicitly acknowledged that existing American museums were not designed with children in mind. Although museums at the turn of the century viewed themselves as institutions of public education, their exhibits were often not made accessible for children, who may have struggled with simple design features like the height of exhibit cases, or the language of interpretive labels.[101] Furthermore, touching objects was often prohibited, limiting visitors' ability to interact with museum objects.

The founders of the Brooklyn Children's Museum were concerned with education and realized that no other institution had attempted to establish "a Museum that will be of especial value and interest to young people between the ages of six and twenty years."[102] Their goal was to gain children's interest and "to stimulate their powers of observation and reflection" as well as to "illustrate by collections of pictures, cartoons, charts, models, maps and so on, each of the important branches of knowledge which is taught in elementary schools."[100]

Anna Billings Gallup, the museum's curator from 1904 to 1937, encouraged a learning technique that allowed children to "discover" information by themselves through touching and examining objects. Visitors to the museum were able to compare the composition, weight, and hardness of minerals, learn to use a microscope to examine natural objects, and build their own collections of natural objects to be displayed in a special room of the museum.[103] In addition to emphasis on allowing interaction with objects, Gallup also encouraged learning through play. She believed learning at the Brooklyn Children's Museum should be "pure fun", and to this end developed nature clubs, held field trips, brought live animals into the museum, and hired gallery instructors to lead children in classification games about animals, shells, and minerals.[104] Other children's museums of the early twentieth century used similar techniques that emphasized learning through experience.

Children's museums often emphasize experiential learning through museum interactives, sometimes leading them to have very few or no physical collection items. The Brooklyn Children's Museum and other early children's museums grew out of the tradition of natural history museums, object-centered institutions. Over the course of the twentieth century, the children's museums slowly began to discard their objects in favor of more interactive exhibits. While children's museums are a more extreme case, it is important to note that during the twentieth century, more and more museums have elected to display fewer objects and offer more interpretation than museums of the nineteenth century.[105] Some scholars argue that objects, while once critical to the definition of a museum, are no longer considered vital to many institutions because they are no longer necessary to fulfill the roles we expect museums to serve as museums focus more on programs, education, and their visitors.[106]

After the Brooklyn Children's Museum opened in 1899, other American museums followed suit by opening small children's sections of their institutions designed with children in mind and equipped with interactive activities, such as the Smithsonian's children's room opened in 1901.[107] The Brooklyn Children's Museum also inspired other children's museums either housed separately or even developed completely independently of parent museums, like the Boston Children's Museum (1913), The Children's Museum of Detroit Public Schools (1915), and the Children's Museum of Indianapolis (1925).[108] The number of children's museums in the United States continued to grow over the course of the twentieth century, with over 40 museums opened by the 1960s and more than 70 children's museums opened to the public between 1990 and 1997.[109]

International professional organizations of children's museums include the Association of Children's Museums (ACM), which was formed in 1962 as the American Association of Youth Museums (AAYM) and in 2007 counted 341 member institutions in 23 countries,[99] and The Hands On! Europe Association of Children's Museum (HO!E), established in 1994, with member institutions in 34 countries as of 2007.[110] Many museums that are members of ACM offer reciprocal memberships, allowing members of one museum to visit all the others for free.

Community

A community museum is a museum serving as an exhibition and gathering space for specific identity groups or geographic areas. In contrast to traditional museums, community museums are commonly multidisciplinary, and may simultaneously exhibit the history, social history, art, or folklore of their communities. They emphasize collaboration with – and relevance to – visitors and other stakeholders.

Design

A design museum is a museum with a focus on product, industrial, graphic, fashion, and architectural design. Many design museums were founded as museums for applied arts or decorative arts and started only in the late 20th century to collect design. Pop-up wndr museum of Chicago was purposefully made to provide visitors with interesting selfie backgrounds.[111][112]

Encyclopedic

Encyclopedic museums are large, mostly national, institutions that offer visitors a plethora of information on a variety of subjects that tell both local and global stories. The aim of encyclopedic museums is to provide examples of each classification available for a field of knowledge. "When 3% of the world's population, or nearly 200 million people, living outside the country of their birth, encyclopedic museums play an especially important role in the building of civil society. They encourage curiosity about the world."[113] James Cuno, President and Director of the Art Institute of Chicago, along with Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum, are two of the most outspoken museum professionals who support encyclopedic museums. They state that encyclopedic museums are advantageous for society by exposing museum visitors to a wide variety of cultures, engendering a sense of a shared human history.[114] Some scholars and archaeologists, however, argue against encyclopedic museums because they remove cultural objects from their original cultural setting, losing their context.[115]

Ethnological and ethnographic

Ethnology museums are a type of museum that focus on studying, collecting, preserving and displaying artifacts and objects concerning ethnology and anthropology. This type of museum usually were built in countries possessing diverse ethnic groups or significant numbers of ethnic minorities. An example is the Ozurgeti History Museum, an ethnographic museum in Georgia.

Historic houses

Within the category of history museums, historic house museums are the most numerous. The earliest projects for preserving historic homes began in the 1850s under the direction of individuals concerned with the public good and the preservation of American history, especially centered on the first president. Since the establishment of America's first historic site at Washington's Revolutionary headquarters at Hasbrouck House in New York, Americans have found a penchant for preserving similar historical structures. The establishment of historic house museums increased in popularity through the 1970s and 1980s as the Revolutionary bicentennial set off a wave of patriotism and alerted Americans to the destruction of their physical heritage. The tradition of restoring homes of the past and designating them as museums draws on the English custom of preserving ancient buildings and monuments. Initially homes were considered worthy of saving because of their associations with important individuals, usually of the elite classes, like former presidents, authors, or businessmen. Increasingly, Americans have fought to preserve structures characteristic of a more typical American past that represents the lives of everyday people including minorities.[116]

While historic house museums compose the largest section within the historic museum category, they usually operate with small staffs and on limited budgets. Many are run entirely by volunteers and often do not meet the professional standards established by the museum industry. An independent survey conducted by Peggy Coats in 1990 revealed that sixty-five percent of historic house museums did not have a full-time staff and 19 to 27 percent of historic homes employed only one full-time employee. Furthermore, the majority of these museums operated on less than $50,000 annually. The survey also revealed a significant disparity in the number of visitors between local house museums and national sites. While museums like Mount Vernon and Colonial Williamsburg were visited by over one million tourists a year, more than fifty percent of historic house museums received less than 5,000 visitors per year.[117]

These museums are also unique in that the actual structure belongs to the museum collection as a historical object. While some historic home museums are fortunate to possess a collection containing many of the original furnishings once present in the home, many face the challenge of displaying a collection consistent with the historical structure. Some museums choose to collect pieces original to the period while not original to the house. Others, fill the home with replicas of the original pieces reconstructed with the help of historic records. Still other museums adopt a more aesthetic approach and use the homes to display the architecture and artistic objects.[118] Because historic homes have often existed through different generations and have been passed on from one family to another, volunteers and professionals also must decide which historical narrative to tell their visitors. Some museums grapple with this issue by displaying different eras in the home's history within different rooms or sections of the structure. Others choose one particular narrative, usually the one deemed most historically significant, and restore the home to that particular period.

Historic sites

_1.jpg)

The U.S. National Park Service defines a historic site as the "location of a significant event, a prehistoric or historic occupation or activity, or a building or structure, whether standing, ruined, or vanished, where the location itself possesses historic, cultural, or archeological value regardless of the value of any existing structure."[119]

Historic sites can also mark public crimes, such as Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia or Robben Island, South Africa. Similar to museums focused on public crimes, museums attached to memorials of public crimes often contain a history component, as is the case at the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum.

Marginalized American people

Museums may concern more general crimes and atrocities, such as American slavery. Often these museums are connected to a particular example, such as the proposed International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, which will treat slavery as an institution with a particular focus on slavery in Charleston and South Carolina's Lowcountry.[120] Museums in cities like Charleston, South Carolina must interact with a broader heritage tourism industry where the history of the majority population is traditionally privileged over the minority.[121][122]

Many specialized museums have been established such as the National LGBT Museum in New York City and the National Women's History Museum planned for the National Mall. The majority of museums across the country that tell state and local history also follow this example. Other museums have a problem interpreting colonial histories, especially at Native American historic sites. However, museums such as the National Museum of the American Indian and Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture and Lifeways in Michigan are working to share authority with indigenous groups and decolonize museums.[123]

Living history

Living history museums combine historic architecture, material culture, and costumed interpretation with natural and cultural landscapes to create an immersive learning environment. These museums include the collection, preservation or interpretation of material culture, traditional skills, and historical processes. Recreated historical settings simulating past time periods can offer the visitor a sense of traveling back in time. They are a type of open-air museum.

Two main interpretation styles dominate the visitor experience at living history museums: first and third person interpretation. In first person interpretation, interpreters assume the persona, including the speech patterns, behaviors, views, and dress of a historical figure from the museum's designated time period. In third person interpretation, the interpreters openly acknowledge themselves to be a contemporary of the museum visitor. The interpreter is not restricted by being in-character and can speak to the visitor about society from a modern-day perspective.

The beginnings of the living history museum can be traced back to 1873 with the opening of the Skansen Museum near Stockholm, Sweden. The museum's founder, Artur Hazelius, began the museum by using his personal collection of buildings and other cultural materials of pre-industrial society.[124] This museum began as an open-air museum and, by 1891, had several farm buildings in which visitors could see exhibits and where guides demonstrated crafts and tools.[125]

For years, living history museums were relatively nonexistent outside of Scandinavia, though some military garrisons in North America used some living history techniques. Living history museums in the United States were initially established by entrepreneurs, such as John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford, and since then have proliferated within the museum world. Some of the earliest living history museums in the United States include Colonial Williamsburg (1926), Greenfield Village (1929), Conner Prairie Pioneer Settlement (1930s), Old Sturbridge Village (1946), and Plimoth Plantation (1947). Many living history farms and similar farm and agricultural museums have united under an association known as the Association for Living History, Farm, and Agricultural Museums (ALHFAM).[124]

Maritime

Maritime museums are museums that specialize in the presentation of maritime history, culture, or archaeology. They explore the relationship between societies and certain bodies of water. Just as there is a wide variety of museum types, there are also many different types of maritime museums. First, as mentioned above, maritime museums can be primarily archaeological. These museums focus on the interpretation and preservation of shipwrecks and other artifacts recovered from a maritime setting. A second type is the maritime history museum, dedicated to educating the public about humanity's maritime past. Examples are the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park and Mystic Seaport. Military-focused maritime museums are a third variety, of which the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum and Battleship IOWA Museum are examples.

Medical

Medical museums today are largely an extinct subtype of museum with a few notable exceptions, such as the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in Glasgow, Scotland. The origins of the medical museum date back to Renaissance cabinets of curiosities which often featured displays of human skeletal material and other materia medica. Apothecaries and physicians collected specimens as a part of their professional activities and to increase their professional status among their peers.[126] As the medical profession placed greater emphasis on teaching and the practice of materia medica in the late 16th century, medical collections became a fundamental component of a medical student's education.[126] New developments in preserving soft tissue samples long term in spirits appeared in the 17th century, and by the mid-18th-century physicians like John Hunter were using personal anatomical collections as teaching tools.[127] By the early 19th century, many hospitals and medical colleges in Great Britain had built sizable teaching collections. In the United States, the nation's first hospital, the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, already had a collection of plaster casts and crayon drawings of the stages of pregnancy as early as 1762.[128]

Medical museums functioned as an integral part of medical students education through the 19th century and into the early 20th century.[128] Dry and wet anatomical specimens, casts, drawings, oil paintings, and photographs provided a means for medical students to compare healthy anatomical specimens with abnormal, or diseased organs. Museums, like the Mütter Museum, added medical instruments and equipment to their collections to preserve and teach the history of the medical profession. By the 1920s, medical museums had reached their nadir and began to wane in their importance as institutes of medical knowledge and training. Medical teaching shifted towards training medical students in hospitals and laboratories, and over the course of the 20th century most medical museums disappeared from the museum horizon. The few surviving medical museums, like the Mütter Museum, have managed to survive by broadening their mission of preserving and disseminating medical knowledge to include the general public, rather than exclusively catering to medical professionals.

Memorial

Memorial museums are museums dedicated both to educating the public about and commemorating a specific historic event, usually involving mass suffering. The concept gained traction throughout the 20th century as a response to the numerous and well publicized mass atrocities committed during that century. The events commemorated by memorial museums tend to involve mostly civilian victims who died under "morally problematic circumstances" that cannot easily be interpreted as heroic. There are frequently unresolved issues concerning the identity, culpability, and punishment of the perpetrators of these killings and memorial museums often play an active research role aimed at benefiting both the victims and those prosecuting the perpetrators.[129]

Today there are numerous memorial museums including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Toul Sleng Museum of Genocidal Crimes in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, the District Six Museum in Cape Town, South Africa, and the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York City. Although the concept of a memorial museum is largely a product of the 20th century, there are museums of this type that focus on events from other periods, an example being the House of Slaves (Maisons des Esclaves) in Senegal which was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1978 and acts as a museum and memorial to the Atlantic slave trade.

Memorial museums differ from traditional history museums in several key ways, most notably in their dual mission to incorporate both a moral framework for and contextual explanations of an event. While traditional history museums tend to be in neutral institutional settings, memorial museums are very often situated at the scene of the atrocity they seek to commemorate. Memorial museums also often have close connections with, and advocate for, a specific clientele who have a special relationship to the event or its victims, such as family members or survivors, and regularly hold politically significant special events.[130] Unlike many traditional history museums, memorial museums almost always have a distinct, overt political and moral message with direct ties to contemporary society. The following mission statement of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is typical in its focus on commemoration, education and advocacy:

"The museum's primary mission is to advance and disseminate knowledge about this unprecedented tragedy; to preserve the memory of those who suffered; and to encourage its visitors to reflect upon the moral and spiritual questions raised by the events of the Holocaust as well as their own responsibilities as citizens of a democracy."[131]

Military and war

Military museums specialize in military histories; they are often organized from a national point of view, where a museum in a particular country will have displays organized around conflicts in which that country has taken part. They typically include displays of weapons and other military equipment, uniforms, wartime propaganda, and exhibits on civilian life during wartime, and decorations, among others. A military museum may be dedicated to a particular or area, such as the Imperial War Museum Duxford for military aircraft, Deutsches Panzermuseum for tanks, the Lange Max Museum for the Western Front (World War I), the International Spy Museum for espionage, The National World War I Museum for World War I, the "D-Day Paratroopers Historical Center" (Normandy) for WWII airborne, or more generalist, such as the Canadian War Museum or the Musée de l'Armée. The U.S. Army and the state National Guards operate 98 military history museums across the United States and three abroad.[132] For the Italian alpine wall one can find the most popular museum of bunkers in the small museum n8bunker at Olang / Kronplatz in the heard of the dolomites of South Tyrol.[133]

Mobile

Mobile museum is a term applied to museums that make exhibitions from a vehicle- such as a van. Some institutions, such as St. Vital Historical Society and the Walker Art Center, use the term to refer to a portion of their collection that travels to sites away from the museum for educational purposes. Other mobile museums have no "home site", and use travel as their exclusive means of presentation. University of Louisiana in Lafayette has also created a mobile museum as part of the graduate program in History. The project is called Museum on the Move.

Natural history

Museums of natural history and natural science typically exhibit work of the natural world. The focus lies on nature and culture. Exhibitions educate the public on natural history, dinosaurs, zoology, oceanography, anthropology, and more. Evolution, environmental issues, and biodiversity are major areas in natural science museums. Notable museums include the Natural History Museum in London, the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in Oxford, the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, and the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Open-air

Open-air museums collect and re-erect old buildings at large outdoor sites, usually in settings of re-created landscapes of the past. The first one was King Oscar II's collection near Oslo in Norway, opened in 1881. In 1907, it was incorporated into the Norsk Folkemuseum.[134] In 1891, inspired by a visit to the open-air museum in Oslo, Artur Hazelius founded the Skansen in Stockholm, which became the model for subsequent open-air museums in Northern and Eastern Europe, and eventually in other parts of the world.[135] Most open-air museums are located in regions where wooden architecture prevail, as wooden structures may be translocated without substantial loss of authenticity. A more recent but related idea is realized in ecomuseums, which originated in France.

Pop-up

A concept developed in the 1990s, the pop-up museum is generally defined as a short term institution existing in a temporary space.[136] These temporary museums are finding increasing favor among more progressive museum professionals as a means of direct community involvement with objects and exhibition. Often, the pop-up concept relies solely on visitors to provide both the objects on display and the accompanying labels with the professionals or institution providing only the theme of the pop-up and the space in which to display the objects, an example of shared historical authority. Due to the flexibility of the pop-up museums and their rejection of traditional structure, even these latter provisions need not be supplied by an institution; in some cases the themes have been chosen collectively by a committee of interested participants while exhibitions designated as pop-ups have been mounted in places as varied as community centers and even a walk-in closet.[137] Some examples of pop-up museums include:

- Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (MAH), which currently hosts collaborative Pop Up Museums around Santa Cruz County.

- Museum of New Art (MONA) – founded in Detroit, Michigan in 1996 this contemporary art museum is generally acknowledged to be the pioneer of the concept of the pop-up museum.[137]

- The Pop-Up Museum of Queer History – a series of pop-up museum events held at various sites across the United States focusing on the history and stories of local LGBT communities.[138]

- Denver Community Museum – a pop-up museum that existed for nine months during 2008–09, located in downtown Denver, Colorado.[139]

- Museum of Motherhood, displayed in and around New York City from 2011 to 2014, now located in St. Petersburg, FL.

Science

Science museums and technology centers or technology museums revolve around scientific achievements, and marvels and their history. To explain complicated inventions, a combination of demonstrations, interactive programs and thought-provoking media are used. Some museums may have exhibits on topics such as computers, aviation, railway museums, physics, astronomy, and the animal kingdom. The Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago is a very popular museum.

Science museums traditionally emphasize cultural heritage through objects of intrinsic value, echoes of the 'curiosity cabinets' of the Renaissance period. These early museums of science represented a fascination with collecting which emerged in the fifteenth century from 'an attempt to manage the empirical explosion of materials that wider dissemination of ancient texts, increased travel, voyages of discovery, and more systematic forms of communication and exchange had produced.[140] Science museums were institutions of authoritative, uncontestable, knowledge, places of 'collecting, seeing and knowing, places where "anybody" might come and survey the evidence of science.[141] Dinosaurs, extensive invertebrate and vertebrate collections, plant taxonomies, and so on – these were the orders of the day. By the nineteenth century, science museums had flourished, and with it 'the capacity of exhibitionary representation to render the world as visible and ordered... part of the instantiation of wider senses of scientific and political certainty' (MacDonald, 1998: 11). By the twentieth century, museums of science had built 'on their earlier emphasis on public education to present themselves as experts in the mediation between the obscure world of science and that of the public.[141]

The nineteenth century also brought a proliferation of science museums with roots in technical and industrial heritage museums.[142] Ordinarily, visitors individually interact with exhibits, by a combination of manipulating, reading, pushing, pulling, and generally using their senses. Information is carefully structured through engaging, interactive displays. Science centers include interactive exhibits that respond to the visitor's action and invite further response, as well as hands-on exhibits that do not offer feedback to the visitor,[142] In general, science centers offer 'a decontextualized scattering of interactive exhibits, which can be thought of as exploring stations of ideas'[143] usually presented in small rooms or galleries, with scant attention paid to applications of science, social political contexts, or moral and ethical implications.

By the 1960s, these interactive science centers with their specialized hands-on galleries became prevalent. The Exploratorium in San Francisco, and the Ontario Science Centre in 1969, were two of the earliest examples of science centers dedicated to exploring scientific principles through hands-on exhibits. In the United States practically every major city has a science center with a total annual visitation of 115 million[144] New technologies of display and new interpretive experiments mark these interactive science centers, and the mantra 'public understanding of science' aptly describes their central activity.[141]