Laptev Sea

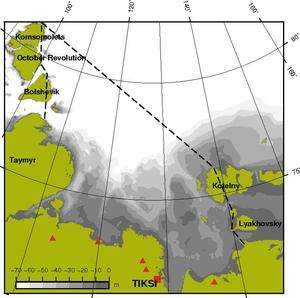

The Laptev Sea (Russian: Мо́ре Ла́птевых, tr. More Laptevykh; Yakut: Лаптевтар Байҕаллара, romanized: Laptevtar Baỹğallara) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the northern coast of Siberia, the Taimyr Peninsula, Severnaya Zemlya and the New Siberian Islands. Its northern boundary passes from the Arctic Cape to a point with co-ordinates of 79°N and 139°E, and ends at the Anisiy Cape. The Kara Sea lies to the west, the East Siberian Sea to the east.

| Laptev Sea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 76°16′7″N 125°38′23″E |

| Type | Sea |

| Basin countries | Russia |

| Surface area | 700,000 km2 (270,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 578 m (1,896 ft) |

| Max. depth | 3,385 m (11,106 ft) |

| Water volume | 403,000 km3 (3.27×1011 acre⋅ft) |

| References | [1][2][3] |

The sea is named after the Russian explorers Dmitry Laptev and Khariton Laptev; formerly, it had been known under various names, the last being Nordenskiöld Sea (Russian: мо́ре Норденшёльда), after explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. The sea has a severe climate with temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) over more than nine months per year, low water salinity, scarcity of flora, fauna and human population, and low depths (mostly less than 50 meters). It is frozen most of the time, though generally clear in August and September.

The sea shores were inhabited for thousands of years by indigenous tribes of Yukaghirs and then Evens and Evenks, which were engaged in fishing, hunting and reindeer husbandry. They were then settled by Yakuts and later by Russians. Russian explorations of the area started in the 17th century. They came from the south via several large rivers which empty into the sea, such as the prominent Lena River, the Khatanga, the Anabar, the Olenyok, the Omoloy and the Yana. The sea contains several dozen islands, many of which contain well-preserved mammoth remains.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Laptev Sea as follows:[4]

On the West. The eastern limit of Kara Sea [Komsomolets Island from Cape Molotov to South Eastern Cape; thence to Cape Vorochilov, Oktiabrskaya Revolutziya Island to Cape Anuchin. Then to Cape Unslicht on Bolshevik Island. Bolshevik Island to Cape Yevgenov. Thence to Cape Pronchisthehev on the main land (see Russian chart No. 1484 of the year 1935)].

On the North. A line joining Cape Molotov to the Northern extremity of Kotelni Island (76°10′N 138°50′E).

On the East. From the Northern extremity of Kotelni Island – through Kotelni Island to Cape Madvejyi. Then through Malyi Island [Little Lyakhovsky Island], to Cape Vaguin on Great Liakhov Island. Thence to Cape Sviatoy Nos on the main land.

Using current geographic names and transcription this definition corresponds to the area shown in the map.

- The sea's border starts at Arctic Cape (formerly Cape Molotov) on Komsomolets Island at 81°13′N 95°15′E and connects to Cape Rosa Luxemburg (Mys Rozy Lyuksemburg), the southeastern cape of the island.

- The next segment crosses Red Army Strait and leads to Cape Vorochilov on October Revolution Island and afterwards through that island to Cape Anuchin at 79°39′37″N 100°21′22″E.

- Next, the border crosses Shokalsky Strait to Cape Unslicht at 79°25′04″N 102°31′00″E on Bolshevik Island. It goes further through the island to Cape Yevgenov at 78°17′N 104°50′E.[5]

- From there, the border goes through Vilkitsky Strait to Cape Pronchishchev at 77°32′57″N 105°54′4″E on the Tamyr peninsula.

- The southern boundary is the shore of the Asian mainland. Prominent features are the Khatanga Gulf (estuary of the Khatanga river) and the delta of the Lena River.

- In the east, the polygon crosses the Dmitry Laptev Strait. It connects Cape Svyatoy Nos at 72.7°N 141.2°E with Cape Vagin at 73°26′0″N 139°50′0″E in the very east of Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island.

- Next, the Laptev Sea border crosses Eterikan Strait to Little Lyakhovsky Island (aka Malyi Island) at 74.0833°N 140.5833°E up to Cape Medvezhiy.

- Finally, there is a segment through Kotelny Island to Cape Anisy, its northernmost headland 76°10′N 138°50′E.

- The last link reaches from there back to Arctic Cape.

Geography

The Lena River, with its large delta, is the biggest river flowing into the Laptev Sea, and is the second largest river in the Russian Arctic after Yenisei.[6] Other important rivers include the Khatanga, the Anabar, the Olenyok or Olenek, the Omoloy and the Yana.

The sea shores are winding and form gulfs and bays of various sizes. The coastal landscape is also diverse, with small mountains near the sea in places.[3] The main gulfs of the Laptev Sea coast are the Khatanga Gulf, the Olenyok Gulf, the Buor-Khaya Gulf and the Yana Bay.[1]

There are several dozens of islands with the total area of 3,784 km2 (1,461 sq mi), mostly in the western part of the sea and in the river deltas. Storms and currents due to the ice thawing significantly erode the islands, so the Semenovsky and Vasilievsky islands (74°12"N, 133°E) which were discovered in 1815 have already disappeared.[1] The most significant groups of islands are Severnaya Zemlya, Komsomolskaya Pravda, Vilkitsky and Faddey, and the largest individual islands are Bolshoy Begichev (1764 km2), Belkovsky (500 km2), Maly Taymyr (250 km2), Stolbovoy (170 km2), Starokadomsky (110 km2), and Peschanyy (17 km2).[3] (see Islands of the Laptev Sea)

More than half of the sea (53%) rests on a continental shelf with the average depths below 50 meters (160 ft), and the areas south from 76°N are shallower than 25 m.[7] In the northern part, the sea bottom sharply drops to the ocean floor with the depth of the order of 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) (22% of the sea area). There it is covered with silt, which is mixed with ice in the shallow areas.[1][2][3]

The Laptev Sea is bound to the south by the East Siberian Lowland, an alluvial plain mainly composed of sediments of marine origin dating back to the time when the whole area was occupied by the Verkhoyansk Sea, an ancient sea at the edge of the Siberian Craton in the Permian period. As centuries went by, gradually, most of the area limiting the sea to the south became filled with the alluvial deposits of modern rivers.[8]

Climate

The climate of the Laptev Sea is Arctic continental and, owing to the remoteness from both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, is one of the most severe among the Arctic seas. Polar night and midnight sun last about 3 months per year on the south and 5 months on the north. Air temperatures stay below 0 °С 11 months a year on the north and 9 months on the south. The average temperature in January (coldest month) varies across the sea between −31 °C (−24 °F) and −34 °C (−29 °F) and the minimum is −50 °C (−58 °F). In July, the temperature rises to 0 °С (maximum 4 °С) in the north and to 5 °С (maximum 10 °С) in the south, however, it may reach 22–24 °С on the coast in August. The maximum of 32.7 °C (90.9 °F) was recorded in Tiksi.[3] Strong winds, blizzards and snow storms are common in winter. Snow falls even in summer and is alternating with fogs.[1][2]

The winds blow from south and south-west in winter with the average speed of 8 m/s which subsides toward the spring. In summer, they change direction to the northerly, and their speed is 3–4 m/s. Relatively weak winds result in low convection in the surface waters, which occurs only to the depth of 5–10 meters.[3]

Ice

The Laptev Sea is a major source of arctic sea ice. With an average outflow of 483,000 km2 per year over the period 1979–1995, it contributes more sea ice than the Barents Sea, Kara Sea, East Siberian Sea and Chukchi Sea combined. Over this period, the annual outflow fluctuated between 251,000 km2 in 1984–85 and 732,000 km2 in 1988–89. The sea exports substantial amounts of sea ice in all months but July, August and September.[9]

Ice formation starts in September on the north and October on the south. It results in a large continuous sheet of ice, with the thickness up to 2 meters (6 ft 7 in) in the south-eastern part of the sea as well as near the coast.[9] The coastal sheet ends at the water depth of 20–25 m which occurs at several hundred kilometers from the shore, thus this coastal ice covers some 30% of the sea area. Ice is drifting north to this coastal band,[3] and several polynyas are formed by the warm south winds around there. They have various names, such as the Great Siberian Polynya, and can stretch over many hundreds kilometers.[3] The ice sheet starts melting in late May-early June, creating fragmented ice agglomerates on the north-west and south-east and often revealing remains of the mammoths. The ice formation varies from year to year, with the sea either clear or completely covered with ice.[1]

Hydrology

The sea is characterized by the low water temperatures, which ranges from −1.8 °C (28.8 °F) in the north to −0.8 °C (30.6 °F) in the south-eastern parts. The medium water layer is warmer, up to 1.5 °С because it is fed by the warm Atlantic waters. It takes them 2.5–3 years to reach the Laptev Sea from their formation near Spitsbergen.[3] The deeper layer is colder at about −0.8 °С. In summer, the surface layer in the ice-free zones warms up by the sun up to 8–10 °С in the bays and 2–3 °С in the open sea, and remains close to 0 °С under ice. The water salinity is significantly affected by the thawing of ice and river runoff. The latter amounts to about 730 km3 and would form a 135 cm freshwater layer over the entire sea; it is the second largest in the world after the Kara Sea. The salinity values vary in winter from 20–25‰ (parts per thousand) in the south-east to 34‰ in the northern parts of the sea; it decreases in summer to 5–10‰ and 30–32‰ respectively.[1][2]

Most of the river runoff (about 70% or 515 km3/year) is contributed by the Lena River. Other major contributions are from Khatanga (more than 100 km3), Olenyok (35 km3), Yana (greater than 30 km3) and Anabar (20 km3), with other rivers contributing about 20 km3. Owing to the ice melting season, about 90% of the annual runoff occurs between June and September with 35–40% in August alone, whereas January contributes only 5%.[3]

Sea currents form a cyclone consisting of the southward stream near Severnaya Zemlya which reaches the continental coast and flows along it from west to east. It is then amplified by the Lena River flow and diverts to the north and north-west toward the Arctic Ocean. A small part of the cyclone leaks through the Sannikov Strait to the East Siberian Sea. The cyclone has a speed of 2 cm/s which decreases toward the center. The center of the cyclone drifts with time that slightly alters the flow character.[3]

The tides are mostly semi-diurnal (rise twice a day), with the average amplitude of 0.5 meters (1 ft 8 in). In the Khatanga Gulf it may reach 2 m because of the funnel-like shape of the gulf.[1] This tidal wave is then noticeable up to the unusually long distance of 500 km up to the Khatanga River – the tidal wave is damped at much shorter distance in other rivers of the Laptev Sea.[3]

The seasonal variations of the sea level are relatively small – the sea level rises up to 40 cm (16 in) in summer near the river deltas and lowers in winter. Wind-induced changes are observed all through the year, but are more frequent in autumn when the winds are strong and steady. In general, the sea level rises with northern and lowers with southern winds, but depending on the area, the maximum amplitude is observed for a specific wind direction (e.g. western and north-western in the south-eastern part of the sea). They average amplitudes are 1–2 m and may exceed 2.5 meters (8 ft 2 in) near Tiksi.[1][3]

Owing to the weak winds and shallow waters, the sea is relatively calm with the waves typically within 1 meter (3 ft 3 in). In July–August waves up to 4–5 m are observed near the sea center, and they may reach 6 meters (20 ft) in autumn.[3]

History and exploration

The coast of the Laptev Sea was inhabited for ages by the native peoples of northern Siberia such as Yukaghirs and Chuvans (sub-tribe of Yukaghirs).[10] Those tribes were engaged in fishing, hunting and reindeer husbandry, as reindeer sleds were essential for transportation and hunting. They were joined and absorbed by Evens and Evenks around the 2nd century and later, between 9th and 15th centuries, by much more numerous Yakuts. All those tribes moved north from the Baikal Lake area avoiding confrontations with Mongols. Whereas they all practiced shamanism, they spoke different languages.[11][12][13][14]

Russians started exploring the Laptev Sea coast and the nearby islands some time in the 17th century, going through the rivers emptying into the sea. Many early explorations were likely unreported, as indicated by finding of graves on some islands by their official discoverers. In 1629, Siberian Cossacks went through the Lena River and reached its delta. They left a note that the river flows into a sea. In 1633, another group reached the delta of Olenyok.[15]

By 1712, Yakov Permyakov and Merkury Vagin explored the eastern part of the Laptev Sea and discovered Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island.[16] However, they were killed on the way back from their expedition by mutineering team members. In 1770, the merchant Ivan Lyakhov revisited the islands and then asked a government permission to commercially develop their ivory resources. Catherine II granted the permission and named the islands after Lyakhov. While exploring the area in the 1770s, Lyakhov described several other islands, including Kotelny, which he named so after a large kettle (Russian: котёл – kotel) left there by previous visitors. He also established first permanent settlements on those islands.[17][18]

In 1735, Russian explorer of Siberia Vasili Pronchishchev sailed from Yakutsk down the Lena River on his sloop Yakutsk. He explored the eastern coast of the Lena delta, and stopped for wintering at the mouth of the Olenyok River. Unfortunately many members of his crew fell ill and died, mainly owing to scurvy. Despite these difficulties, in 1736, he reached the eastern shore of the Taymyr Peninsula and went north surveying its coastline. Pronchishchev and his wife succumbed to scurvy and died on the way back.[19][20] Maria Pronchishcheva Bay in the Laptev Sea is named after the wife of Pronchishchev.

During the 1739–1742 Great Northern Expedition, Russian Arctic explorer and Vice Admiral Dmitry Laptev described the sea coastline from the mouth of the Lena River, along the Buor-Khaya and Yana gulfs, to the strait that bears his name, Dmitry Laptev Strait. As part of the same expedition, Dmitry's cousin Khariton Laptev's led a party that surveyed the coast of the Taimyr Peninsula starting from the mouth of the Khatanga River.[21][22]

Detailed mapping of the coast of the Laptev Sea and New Siberian Islands was performed by Pyotr Anjou, who in 1821–1823 traveled some 14,000 km (8,700 mi) over the region on sledges and small boats, searching for the Sannikov Land and demonstrating that large-scale coastal observations can be performed without ships. Anzhu Islands (the northern part of New Siberian Islands) were named after him.[23][24] In 1875, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld was the first to travel across the whole sea on a steamship Vega.[15]

In 1892–1894, and again in 1900–1902, Baron Eduard von Toll explored the Laptev Sea in the course of two separate expeditions. On the ship Zarya, Toll carried out geological and geographical surveys in the area on behalf of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences. In his last expedition Toll disappeared off the New Siberian Islands under mysterious circumstances.[17][25] Toll noted[26] sizable and economically significant accumulations of perfectly preserved fossil ivory in recent beaches, drainage areas, river terraces and river beds within the New Siberian Islands. The later scientific studies demonstrated that the ivory accumulated over a period of some 200,000 years.[27][28][29]

Naming

The Laptev Sea changed its name several times. It was apparently known as the Tartar Sea (Russian: Татарское мо́ре) in the 16th century, as the Lena Sea (Russian: Ленское мо́ре) in the 17th century, as the Siberian Sea (Russian: Сибирское мо́ре) in the 18th century and as the Icy Sea (Russian: Ледовитое мо́ре) in the 19th century. It acquired its name as Nordenskjold Sea (Russian: мо́ре Норденшельда) in 1893.[30] On 27 June 1935, the sea finally received its current name after the cousins Dmitry Laptev and Khariton Laptev who first mapped its shores in 1735–1740.[2][31]

Flora and fauna

Both flora and fauna are scarce owing to the harsh climate. Vegetation of the sea is mostly represented by diatoms, with more than 100 species. In comparison, the number of green algae, blue-green algae and flagellate species is about 10 each. The phytoplankton is characteristic of brackish waters[7] and has a total concentration of about 0.2 mg/L. There are about 30 species of zooplankton with the concentration reaching 0.467 mg/L.[6] The coastal flora mainly consists of mosses and lichens and a few flowering plants including Arctic poppy (Papaver radicatum), Saxifraga, Draba and small populations of polar (Salix polaris) and creeping (Salicaceae) willows.[32] Rare vascular plants include species of Cerastium and Saxifraga. Non-vascular plants include the moss genera Detrichum, Dicranum, Pogonatum, Sanionia, Bryum, Orthothecium and Tortura, as well as the lichen genera Cetraria, Thamnolia, Cornicularia, Lecidea, Ochrolechia and Parmelia.[33]

Permanent mammal species include ringed seal (Phoca hispida), bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus), harp seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus), walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus), Arctic fox (Alopex lagopus),[34] reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) wolf (Canis lupus), ermine (Mustela erminea), Arctic hare (Lepus timidus) and polar bear (Ursus maritimus), whereas beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) visit the region seasonally.[35] The walrus of the Laptev Sea is sometimes distinguished as a separate subspecies Odobenus rosmarus laptevi, though this attribution is questioned.[36] There are several dozens species of birds. Some belong to permanent (tundra) species, such as snow bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis), purple sandpiper (Calidris maritima), snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) and brent goose and other make large colonies on the islands and sea shores. The latter include little auk (Alle alle), black-legged kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla), black guillemot (Cepphus grylle), ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea), uria, charadriiformes and glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus). Among other bird species are skua, sterna, northern fulmar, (Fulmarus glacialis), ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea), glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus), Ross's gull (Rhodostethia rosea), long-tailed duck (Clangula hyemalis), eider, loon and willow grouse (Lagopus lagopus).[32][37] There are 39 fish species, mostly typical of braskish environment;[7] the major ones are grayling and Coregonus (whitefishes), such as muksun (Coregonus muksun), broad whitefish (Coregonus nasus) and omul (Coregonus autumnalis). Also common are sardine, Arctic cisco, Bering cisco, polar smelt, saffron cod, polar cod, flounder and Arctic char and inconnu.[1]

In 1985, the Ust-Lena Nature Reserve was established in the delta (from Russian: устье – ust, meaning delta) of the Lena River with an area of 14,300 km2. In 1986, New Siberian Islands were included into the reserve. The reserve hosts numerous plants (402 species), fishes (32 species), birds (109 species) and mammals (33 species).[38]

Human activities

The coast of the sea is shared by the Sakha Republic (Anabarsky, Bulunsky District and Ust-Yansky districts) on the east and Krasnoyarsk Krai (Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District) of Russia on the west. The coastal settlements are few and small, with the typical population of a few hundred or less. The only exception is Tiksi (population 5,873), which is the administrative center of the Bulunsky District.

Fishery and navigation

Fishery and hunting have relatively small volume and are mostly concentrated in the river deltas.[1][3] Data are available for the Khatanga Bay and deltas of the Lena and Yana rivers from 1981 to 1991 which translate into about 3,000 tonnes of fish annually. Extrapolated, they give the following annual estimates (in thousand tonnes) by species: sardine (1.2), Arctic cisco (2.0), Bering cisco (2.7), broad whitefish (2.6), Muksun (2.4) and others (3.6).[34] Hunting sea mammals is only practiced by native people. In particular, walrus hunting is only allowed by scientific expeditions and local tribes for subsistence.[39]

Despite freezing, navigation is a major human activity on the Laptev Sea with the major port in Tiksi. During Soviet times, the Laptev Sea coastal areas experienced a limited boom owing to the first icebreaker convoys plying the Northern Sea Route and the creation of the Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route. The route was difficult even for icebreakers – so Lenin (pictured) and her convoy of five ships were trapped in ice in the Laptev Sea around September 1937. They spent an enforced winter there and were rescued by another icebreaker Krasin in August 1938.[40] The major transported goods were timber, fur and construction materials.[1] Tiksi had an active airport, and Nordvik harbor further west was "a growing town,"[40] though it was closed in the mid-1940s.[41][42]

After the break-up of the Soviet Union commercial navigation in the Siberian Arctic went into decline in the 1990s. More or less regular shipping is to be found only from Murmansk to Dudinka in the west and between Vladivostok and Pevek in the east. Ports between Dudinka and Pevek see next to no shipping at all. Logashkino was abandoned in 1998 and is now a ghost town.[43]

Mining

In the 1930, deposits of coal, oil and salt were discovered around the Nordvik Bay. In order to explore them in the extreme Arctic conditions, a Gulag penal labor camp was established in Nordvik. Drilling revealed only small, shallow oil pockets in connection with salt structures with little commercial significance. However the salt was extracted on a large scale by means of forced laborers in a penal colony. From the 1930s onwards Nordvik became an important source of salt supply for the northern fisheries. Although the original prospects for oil at Nordvik did not materialize, experience was gained in the exploration for hydrocarbons within the continuous permafrost zones. This experience proved invaluable in the later exploration and exploitation of the massive oil and gas fields of Western Siberia. The penal colony was closed and its traces erased in the mid-1940s right before Americans arrived in Nordvik as allies of the Soviet Union.[41][42]

In 2017, Rosneft found oil in the Laptev Sea at its Tsentralno-Olginskaya-1 well.[44]

In the Anabar District of Sakha, in the village of Mayat there is one of the northern-most diamond mines.[45] There are also tin and gold mines in the Ust-Yansky District.[46]

Research

The meteorological station of Tiksi has been renovated in 2006 (for example, it has internet connection and security cameras with a wireless interface) and has become part of the Atmospheric Observatory program of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration agency. The program aims at long-term, systematic and thorough measurements of clouds, radiation, aerosols, surface energy fluxes and chemistry in the Arctic. It is based on four Arctic stations at one of the world's northernmost settlements, namely Eureka and Alert in Canada (in particular, Alert is the northernmost permanently inhabited place on Earth, only 817 km (508 mi) from the North Pole[47]), Tiksi in Russia, and Utqiagvik in Alaska.[48]

Pollution

The water pollution is relatively low and mostly originates from the numerous plants and mines standing on the Lena, Yana and Anabar rivers. Their waste is contaminated with phenols (0.002–0.007 mg/L), copper (0.001–0.012 mg/L) and zinc (0.01–0.03 mg/L) and is continuously washed down the rivers into the sea. Another regular polluter is the coastal Urban-type settlement of Tiksi. Occasional petrol spills occurred due to navigation and petrol mining.[6] Another major contaminant is associated with floating and sunken wood in the sea, due to decades of rafting activities. As a result, the phenol concentration in the Laptev Sea is the highest over the Arctic waters.[34]

- Laptev Sea. Sunset.

- Laptev Sea. Ice hummocks.

- Hivus-10 hovercraft on Laptev Sea

See also

References

- Laptev Sea, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- Laptev Sea, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- A. D. Dobrovolskyi and B. S. Zalogin Seas of USSR. Laptev Sea, Moscow University (1982) (in Russian)

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "Topographic maps T-48-XIII, XIV, XV – 1:200 000". Топографические карты (in Russian). Retrieved 2012-09-17.

- Ecological assessment of pollution in the Russian Arctic region, Global International Waters Assessment Final Report

- Arnoldus Schytte Blix (2005) Arctic animals and their adaptations to life on the edge, ISBN 82-519-2050-7 pp. 57–58

- Sea basins and land of the East Siberian Lowland

- V. Alexandrov; et al. (2000). "Sea ice circulation in the Laptev Sea and ice export to the Arctic Ocean: Results from satellite remote sensing and numerical modeling" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (C5): 17143–17159. Bibcode:2000JGR...10517143A. doi:10.1029/2000JC900029. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Чуванцы. Narodru.ru. Retrieved on 2013-03-21.

- Yukaghirs, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- Evenks, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- Bella Bychkova Jordan, Terry G. Jordan-Bychkov Siberian Village: Land and Life in the Sakha Republic, U of Minnesota Press, 2001 ISBN 0-8166-3569-2 p. 38

- Evens Archived 2012-07-12 at the Wayback Machine, Novosibirsk University (in Russian)

- Лаптевых море (in Russian)

- Новосибирские острова, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- M. I. Below По следам полярных экспедиций. Часть II. На архипелагах и островах

- Lyakhov Ivan, Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Григорій Спасскій Сибирскій вѣстник, Объемы 17–18, Въ Тип. Департамента народного просвѣщенія, 1822

- V. V. Bogdanov (2001) Первая Русская полярница Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Priroda, Vol. 1

- Dmitri Laptev, Khariton Laptev, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- Cousins Laptev (in Russian)

- Анжу Пётр Фёдорович, Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Анжу Пётр Фёдорович. Funeral-spb.narod.ru. Retrieved on 2013-03-21.

- William Barr, (1980) "Baron Eduard von Toll’s Last Expedition: The Russian Polar Expedition, 1900–1903", Arctic, 34 (3), p. 201–224

- Eduard Von Toll (1895) Wissenschaftliche Resultate der Von der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften sur Erforschung des Janalandes und der Neusibirischen Inseln in den Jahren 1885 und 1886 Ausgesandten expedition. [Scientific Results of the Imperial Academy of Sciences of the Investigation of Janaland and the New Siberian Islands from the Expeditions Launched in 1885 and 1886] Abtheilung III: Die fossilen Eislager und ihre Beziehungen su den Mammuthleichen. Memoires de L'Academie imperials des Sciences de St. Petersbouro, VII Serie, Tome XLII, No. 13, Commissionnaires de I'Academie Imperiale des sciences, St. Petersbourg, Russia.

- Andreev, A.A., G. Grosse, L. Schirrmeister, S.A. Kuzmina, E. Y. Novenko, A.A. Bobrov, P.E. Tarasov, B.P. Ilyashuk, T.V. Kuznetsova, M. Krbetschek, H. Meyer, and V.V. Kunitsky, 2004, "Late Saalian and Eemian palaeoenvironmental history of the Bol'shoy Lyakhovsky Island (Laptev Sea region, Arctic Siberia)" (PDF). Archived from the original on October 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-12.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link), 3.41 MB PDF file, Boreas. vol. 33, pp. 319–348.

- Makeyev, V.M., D.P. Ponomareva, V.V. Pitulko, G.M. Chernova and D.V. Solovyeva, 2003, Vegetation and Climate of the New Siberian Islands for the past 15,000 Years. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 56–66.

- Ivanova, A. M., V. Ushakov, G. A. Cherkashov, and A. N. Smirnov, 1999, Placer Minerals of the Russian Arctic Shelf. Polarforschung. vol. 69, pp. 163–167.

- "History of Norilsk and Taimyr" Archived 2010-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, a website from Krasnoyarsk region (Russian)

- Лаптевых, Словарь географических названий (Dictionary of geographical names)

- Северная Земля. Часть II (Severnaya Zemlyua, part 2, in Russian)

- Manfred Bolter and Hiroshi Kanda (1997). "Preliminary results of botanical and microbiological investigations on Severnaya Zemlya 1995" (PDF). Proc. NIPR Symp. Polar Biol. 10: 169–178.

- S. Heileman and I. Belkin Laptev Sea: LME #56 Archived 2013-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, in Sherman, K. and Hempel, G. (Editors) 2008. The UNEP Large Marine Ecosystem Report

- Список видов морских млекопитающих, встречающихся в море Лаптевых Archived 2010-04-03 at the Wayback Machine. 2mn.org. Retrieved on 2013-03-21.

- Charlotte Lindqvist; et al. (2009). "The Laptev Sea walrusOdobenus rosmarus laptevi: an enigma revisited". Zoologica Scripta. 38 (2): 113. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2008.00364.x.

- Bird Observations in Severnaya Zemlya, Siberia. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2010-10-19.

- Усть-Ленский государственный природный заповедник Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine (official we site)

- Mammals in the Seas: Pinniped species summaries and report on sirenians. Volume 2, Food & Agriculture Org., 1979, ISBN 92-5-100512-5 p. 57

- William Barr (March 1980). "The Drift of Lenin's Convoy in the Laptev Sea, 1937–1938" (PDF). Arctic. 33 (1): 3–20. doi:10.14430/arctic2543. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- Нордвикские записки (notes of the Nordvik expedition), Кровь, пот и соль «Нордвикстроя» Archived 2011-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- посёлок Нордвик, dead-cities.ru (in Russian)

- Resolution No. 443 of 29 September 1998 On Exclusion of Inhabited Localities from the Records of Administrative and Territorial Division of the Sakha (Yakutia) Republic

- "Rosneft Discovers Oil in Laptev Sea". maritime-executive.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Diamonds of Anabar". ykt.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "XuMuK.ru - ГОРНАЯ КОМПАНИЯ ЮЖНАЯ, ООО - Добыча руд и песков драгоценных металлов (золота, серебра и металлов платиновой группы), регион РЕСПУБЛИКА САХА (ЯКУТИЯ)". www.xumuk.ru. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Reynolds, Lindor (31 August 2000). "Life is cold and hard and desolate at Alert, Nunavut". Guelph Mercury. Retrieved 16 March 2010. ("Twice a year, the military resupply Alert, the world's northernmost settlement.")

- A Study of Environmental Arctic Change (SEARCH) Arctic Atmospheric Observatories, NOAA

External links