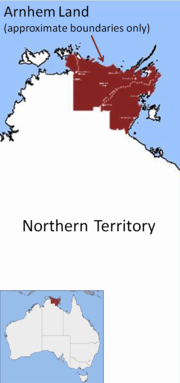

Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land is a historical region of the Northern Territory of Australia. It is located in the north-eastern corner of the territory and is around 500 km (310 mi) from the territory capital, Darwin. In 1623, Dutch East India Company captain Willem Joosten van Colster (or Coolsteerdt) sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria and Cape Arnhem is named after his ship, the Arnhem, which itself was named after the city of Arnhem in the Netherlands.

| Arnhem Land Northern Territory | |

|---|---|

Approximate location of Arnhem Land | |

| Population | 16,230 (2007)[1] |

| • Density | 0.1673/km2 (0.4334/sq mi) |

| Area | 97,000 km2 (37,451.9 sq mi) |

| Territory electorate(s) | Arafura, Nhulunbuy, Arnhem |

| Federal Division(s) | Lingiari |

The area covers about 97,000 km2 and has an estimated population of 16,000, of whom 12,000 are indigenous. The region's service hub is Nhulunbuy, 600 km east of Darwin, set up in the early 1970s as a mining town (bauxite). Other major population centres are Yirrkala (just outside Nhulunbuy), Gunbalanya (formerly Oenpelli), Ramingining, and Maningrida.

A substantial proportion of the population, which is mostly Aboriginal, lives on small outstations. This outstation movement started in the early 1980s. Many Aboriginal groups moved to usually very small settlements on their traditional lands, often to escape the problems on the larger townships. These population groups have very little Western influence culturally speaking, and Arnhem Land is arguably one of the last areas in Australia that could be seen as a completely separate country. Many of the region's leaders have called and continue to call for a treaty that would allow the Yolngu to operate under their own traditional laws.

In 2013–14, the entire region contributed around $1.3 billion or 7% to the Northern Territory's gross state product, mainly through bauxite mining.[2] In 2019, it was announced that NASA had chosen Arnhem Land as the location for a space launch facility.[3]

History

Arnhem Land has been occupied by indigenous people for tens of thousands of years and is the location of the oldest-known stone axe, which scholars believe to be 35,500 years old.[4] The Gove Peninsula was heavily involved in the defence of Australia during World War II.

At least since the 18th century (and probably earlier) Muslim traders from Makassar of Sulawesi visited Arnhem Land each year to trade, harvest, and process sea cucumbers or trepang. This marine animal is highly prized in Chinese cuisine, for folk medicine, and as an aphrodisiac.

This Macassan contact with Australia is the first recorded example of interaction between the inhabitants of the Australian continent and their Asian neighbours.[5]

This contact had a major effect on local indigenous Australians. The Makassans exchanged goods such as cloth, tobacco, knives, rice, and alcohol for the right to trepang coastal waters and employ local labour. Makassar pidgin became a lingua franca along the north coast among several indigenous Australian groups who were brought into greater contact with each other by the seafaring Makassan culture.[5]

These traders from the southwest corner of Sulawesi also introduced the word balanda for white people, long before western explorers set foot on the coasts of northern Australia. In Arnhem Land, the word is still widely used today to refer to white Australians. The Dutch started settling in Sulawesi Island in the early 17th century.

Archeological remains of Makassar contact, including trepang processing plants (drying, smoking) from the 18th and 19th centuries, are still found at Australian locations such as Port Essington and Groote Eylandt. The Makassans also planted tamarind trees (native to Madagascar and East Africa).[5] After processing, the sea slugs were traded by the Makassans to Southern China.

In 2014, an 18th-century Chinese coin was found in the remote area of Wessel Islands off the coast on a beach on Elcho Island during a historical expedition. The coin was found near previously known Macassan trepanger fishing sites (sea cucumber fishing) where several other Dutch coins have been discovered nearby, but never a Chinese coin. The coin was probably made in Beijing around 1735. [6]

Geography

The area is from Port Roper on the Gulf of Carpentaria around the coast to the East Alligator River, where it adjoins Kakadu National Park. The major centres are Jabiru on the Kakadu National Park border, Maningrida at the Liverpool River mouth, and Nhulunbuy (also known as Gove) in the far north-east, on the Gove Peninsula. Gove is the site of large-scale bauxite mining with an associated alumina refinery. Its administrative centre is the town of Nhulunbuy, the fourth-largest population centre in the Northern Territory.

The climate of Arnhem Land is tropical monsoon with a wet and dry season. The temperature has little seasonal variation; however, it can range from overnight lows of 15 °C (59 °F) in the dry season (April to September) to daily highs of 33 °C (91 °F) in the wet season (October to March).

Demographics

In 1931, an area of 96,000 square kilometres (37,000 sq mi) was proclaimed as an Aboriginal reserve, named Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve. As of 2007 the Land Trust held about 100,000 square kilometres (39,000 sq mi) as Aboriginal freehold land (with the exception of mining leases);[7] it remains one of the largest parcel of Aboriginal-owned land in Australia and is perhaps best known for its isolation, the art of its people, and the strong continuing traditions of its Aboriginal inhabitants. Northeast Arnhem Land is home to the Yolngu people, one of the largest Indigenous groups in Australia, who have succeeded in maintaining a vigorous traditional culture. The Malays and Makassans are believed to have had contact with the coastal Aboriginal groups and traded with them prior to European settlement of Australia.

Film

The 2006 film Ten Canoes captures life in Arnhem Land through a story tapping into the Aboriginal mythic past; it was co-directed by one of the indigenous cast members. The film and the documentary about the making of the film, The Balanda and the Bark Canoes, give a remarkable testimony to the indigenous struggle to keep their culture alive – or rather revive it in the wake of considerable relative modernisation and influence of white (balanda) cultural imposition.[8][9]

Art

The Aboriginal community of Yirrkala, just outside Nhulunbuy, is internationally known for bark paintings, promoting the rights of Indigenous Australians, and as the origin of the yidaki, or didgeridoo. The community of Gunbalanya (previously known as Oenpelli) in Western Arnhem Land is also notable for bark painting. The indigenous inhabitants also create temporary sand sculptures as part of their sacred rituals.

Arnhem Land is also notable for Aboriginal rock art, some examples of which can be found at Ubirr Rock, Injalak Hill, and in the Canon Hill area. Some of these record the early years of European explorers and settlers, sometimes in such detail that Martini–Henry rifles can be identified. They also depict axes, and detailed paintings of aircraft and ships. One remote shelter, several hundred kilometres from Darwin, has a painting of the wharf at Darwin, including building and boats, and Europeans with hats and pipes, some apparently without hands (which they have in their trouser pockets). Near the East Alligator River crossing, a figure was painted of a man carrying a gun and wearing his hair in long pigtails down his back, characteristic of the Chinese labourers brought to Darwin in the late 19th century.

One Yolngu prehistoric stone arrangement at Maccasans Beach near Yirrkala shows the layout of the Macassan praus used for trepang (sea cucumber) fishing in the area. This was a legacy of Yolngu trade links with the people on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. The trading relationship antedated European settlement by some 200 years.

Aboriginal artists in Arnhem Land are primarily represented by Aboriginal Art Centres, nonprofit, community-owned organisations.[10] In East Arnhem Land, primarily Yolngu Matha-speaking artists are promoted by Buku-Larrnggay Mulka in Yirrkala, Bula'bula Arts in Ramingining, Elcho Island Arts and Crafts on Elcho Island, Gapuwiyak Culture and Arts in Gapuwiyak and Milingimbi Art and Culture on Milingimbi Island. In Central Arnhem Land, Maningrida Arts & Culture in Maningrida promotes the work of a diverse range of Kuninjku, Burarra, and Gurrgoni artists, amongst others. In West Arnhem Land, Injalak Arts in Gunbalanya represents mainly Kunwinjku artists. Ngukurr Arts is located on the Roper River in Southern Arnhem Land. Art is also produced on the many islands of Arnhem Land, and there are art centres on the Anindilyakwa speaking Groote Eylandt (Anindilyakwa Art) and the Maung speaking Goulburn Islands (Mardbalk Arts & Crafts).

Homelands

Arnhem Land is also known for embracing the homeland movement, sometimes referred to as the outstation movement.

A focus in recent years by governments about the "viability" of the homelands has caused tensions and uncertainty within the Arnhem Land community.[11]

In September 2008, then Darwin correspondent for The Age, Lindsay Murdoch, wrote: "Elders tell of their fears that Yolngu culture and society will not survive if clans cannot continue to live on and access their land through homelands. They warn that if services are cut, many of the 800 people in the Laynhapuy homelands will be forced to move to towns such as Yirrkala on the Gove Peninsula, creating new law and order problems, while those who stay will be severely disadvantaged."[12]

In response to changes made by the Northern Territory government surrounding reduced support for the homelands in 2009, the indigenous leader Patrick Dodson criticised the Northern Territory government's controversial new policy on remote Aboriginal communities, describing it as a "die on the vine" plan that will "slowly but surely" kill indigenous culture.[13]

Born in the 1930s, Dr Gawirrin Gumana AO is a leader of the Dhalwangu clan. He is one of the most senior Yolŋu alive today and is renowned for his artwork and knowledge of traditional culture and law. In May 2009, he had the following to say about the significance of the homelands to his people:

- "We want to stay on our own land. We have our culture, we have our law, we have our land rights, we have our painting and carving, we have our stories from our old people, not only my people, but everyone, all Dhuwa and Yirritja, we are not making this up.

- I want you to listen to me Government.

- I know you have got the money to help our Homelands. But you also know there is money to be made from Aboriginal land.

- You should trust me, and you should help us to live here, on our land, for my people.

- I am talking for all Yolŋu now.

- So if you can't trust me Government, if you can't help me Government, come and shoot me, because I will die here before I let this happen."[14]

Despite facing government concerns and policy confusion, a number of people have developed commercial enterprises that have centred on using the best elements of their homelands. Indigenous tourism ventures incorporating the controlled use of homelands are now showing signs of success for a select number of Yolngu.[15]

See also

- Arnhem Land tropical savanna

- Gabarnmung – Aboriginal archaeological and rock art site

- Kakadu National Park

- Protected areas of the Northern Territory

- Ubirr

- Wongalara Sanctuary

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2 October 2008). "Australian Demographic Statistics" (PDF). Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- "About East Arnhem Land". Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "NASA's surprise Aussie pick for rocket launch". NewsComAu. 31 May 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- MacKnight, CC (1976). The Voyage to Marege: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84088-4.

- Australian Geographic (August 2014). "18th Century Chinese coin found in Arnhem Land".

- "History". East Arnhemland. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

- Vertigo Productions. "Ten Canoes". Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "The Balanda and the Bark Canoes at the National Film and Sound Archive".

- http://www.ankaaa.org.au/

- Australian Government (30 October 2008). "'Viability of Aboriginal communities'". Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- The Age (26 September 2008). "'The Homelands' Ancient Ties". Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ABC (2 June 2009). "'Killing us softly: Dodson slams outstations plan'". Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- Australian Human Rights Commission (2009). "'Social Justice Report 2009: Chapter 4 Sustaining Aboriginal homeland communities'". Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- "'Bawaka'". 2011. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- Arnhem Land. Its History and Its People. 1954. R. M. & C. H. Berndt. F. W. Cheshire, Melbourne.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arnhem Land. |

- Arnhem Region

- Gove Online Community Website

- Bawaka