Hawaiian Islands

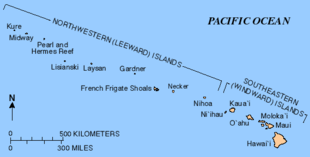

The Hawaiian Islands (Hawaiian: Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets, and seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) from the island of Hawaiʻi in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll. Formerly the group was known to Europeans and Americans as the Sandwich Islands, a name that James Cook chose in honor of the then First Lord of the Admiralty John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. The contemporary name, dating from the 1840s, is derived from the name of the largest island, Hawaiʻi Island. The islands were first known to Europeans after the expedition of Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón in 1527.

| Native name: Mokupuni o Hawai‘i | |

|---|---|

The Windward Islands of Hawaii | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | North Pacific Ocean |

| Total islands | 137 |

| Highest point |

|

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | Hawaii |

| Unincorporated territory | Midway Atoll |

| Largest settlement | Honolulu |

Hawaii is the only U.S. state that is not geographically connected to North America. The state of Hawaii occupies the archipelago almost in its entirety (including the mostly uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands), with the sole exception of Midway Island, which also belongs to the United States, albeit as one of its unincorporated territories within the United States Minor Outlying Islands.

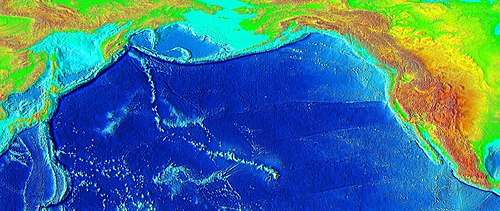

The Hawaiian Islands are the exposed peaks of a great undersea mountain range known as the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain, formed by volcanic activity over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle. The islands are about 1,860 miles (3,000 km) from the nearest continent.[1]

Islands and reefs

The date of the first settlements of the Hawaiian Islands is a topic of continuing debate.[2] Archaeological evidence seems to indicate a settlement as early as 124 AD.[3]

Captain James Cook visited the islands on January 18, 1778,[4] and named them the "Sandwich Islands" in honor of John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, who as the First Lord of the Admiralty was one of his sponsors.[5] This name was in use until the 1840s, when the local name "Hawaii" gradually began to take precedence.[6]

The Hawaiian Islands have a total land area of 6,423.4 square miles (16,636.5 km2). Except for Midway, which is an unincorporated territory of the United States, these islands and islets are administered as Hawaii—the 50th state of the United States.[7]

Main islands

| Island | Nickname | Area | Population (as of 2010) |

Density | Highest point | Elevation | Age (Ma)[8] | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaiʻi[9] | The Big Island | 4,028.0 sq mi (10,432.5 km2) | 185,079 | 45.948/sq mi (17.7407/km2) | Mauna Kea | 13,796 ft (4,205 m) | 0.4 | 19°34′N 155°30′W |

| Maui[10] | The Valley Isle | 727.2 sq mi (1,883.4 km2) | 144,444 | 198.630/sq mi (76.692/km2) | Haleakalā | 10,023 ft (3,055 m) | 1.3–0.8 | 20°48′N 156°20′W |

| Oʻahu[11] | The Gathering Place | 596.7 sq mi (1,545.4 km2) | 953,207 | 1,597.46/sq mi (616.78/km2) | Mount Kaʻala | 4,003 ft (1,220 m) | 3.7–2.6 | 21°28′N 157°59′W |

| Kauaʻi[12] | The Garden Isle | 552.3 sq mi (1,430.5 km2) | 66,921 | 121.168/sq mi (46.783/km2) | Kawaikini | 5,243 ft (1,598 m) | 5.1 | 22°05′N 159°30′W |

| Molokaʻi[13] | The Friendly Isle | 260.0 sq mi (673.4 km2) | 7,345 | 28.250/sq mi (10.9074/km2) | Kamakou | 4,961 ft (1,512 m) | 1.9–1.8 | 21°08′N 157°02′W |

| Lānaʻi[14] | The Pineapple Isle | 140.5 sq mi (363.9 km2) | 3,135 | 22.313/sq mi (8.615/km2) | Lānaʻihale | 3,366 ft (1,026 m) | 1.3 | 20°50′N 156°56′W |

| Niʻihau[15] | The Forbidden Isle | 69.5 sq mi (180.0 km2) | 170 | 2.45/sq mi (0.944/km2) | Mount Pānīʻau | 1,250 ft (381 m) | 4.9 | 21°54′N 160°10′W |

| Kahoʻolawe[16] | The Target Isle | 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km2) | 0 | 0/sq mi (0/km2) | Puʻu Moaulanui | 1,483 ft (452 m) | 1.0 | 20°33′N 156°36′W |

The eight main islands of Hawaii (also called the Hawaiian Windward Islands) are listed here. All except Kahoolawe are inhabited.[17]

Smaller islands, atolls, reefs

Smaller islands, atolls, and reefs (all west of Niʻihau are uninhabited except Midway Atoll) form the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, or Hawaiian Leeward Islands:

- Nihoa (Mokumana)

- Necker (Mokumanamana)

- French Frigate Shoals (Kānemilohaʻi)

- Gardner Pinnacles (Pūhāhonu)

- Maro Reef (Nalukākala)

- Laysan (Kauō)

- Lisianski Island (Papaʻāpoho)

- Pearl and Hermes Atoll (Holoikauaua)

- Midway Atoll (Pihemanu)

- Kure Atoll (Mokupāpapa)

Islets

The state of Hawaii counts 137 "islands" in the Hawaiian chain.[19] This number includes all minor islands and islets (very small islands) offshore of the main islands (listed above) and individual islets in each atoll. These are just a few:

- Ford Island (Mokuʻumeʻume)

- Lehua

- Kaʻula

- Kaohikaipu

- Mānana

- Mōkōlea Rock

- Nā Mokulua

- Molokini

- Mokoliʻi

- Moku Manu

- Moku Ola (Coconut Island, Hawaii)

- Moku o Loʻe (Coconut Island, Oahu)

- Sand Island

- Grass Island

Geology

This chain of islands, or archipelago, developed as the Pacific Plate slowly moved northwestward over a hotspot in the Earth's mantle at a rate of approximately 32 miles (51 km) per million years. Thus, the southeast island is volcanically active, whereas the islands on the northwest end of the archipelago are older and typically smaller, due to longer exposure to erosion. The age of the archipelago has been estimated using potassium-argon dating methods.[20] From this study and others,[21][22] it is estimated that the northwesternmost island, Kure Atoll, is the oldest at approximately 28 million years (Ma); while the southeasternmost island, Hawaiʻi, is approximately 0.4 Ma (400,000 years). The only active volcanism in the last 200 years has been on the southeastern island, Hawaiʻi, and on the submerged but growing volcano to the extreme southeast, Loʻihi. The Hawaiian Volcano Observatory of the USGS documents recent volcanic activity and provides images and interpretations of the volcanism. Kīlauea had been erupting nearly continuously since 1983 when it stopped August 2018.

Almost all of the magma of the hotspot has the composition of basalt, and so the Hawaiian volcanoes are composed almost entirely of this igneous rock. There is very little coarser-grained gabbro and diabase. Nephelinite is exposed on the islands but is extremely rare. The majority of eruptions in Hawaiʻi are Hawaiian-type eruptions because basaltic magma is relatively fluid compared with magmas typically involved in more explosive eruptions, such as the andesitic magmas that produce some of the spectacular and dangerous eruptions around the margins of the Pacific basin.

Hawaiʻi island (the Big Island) is the biggest and youngest island in the chain, built from five volcanoes. Mauna Loa, taking up over half of the Big Island, is the largest shield volcano on the Earth. The measurement from sea level to summit is more than 2.5 miles (4 km), from sea level to sea floor about 3.1 miles (5 km).[23]

Earthquakes

The Hawaiian Islands have many earthquakes, generally caused by volcanic activity. Most of the early earthquake monitoring took place in Hilo, by missionaries Titus Coan, Sarah J. Lyman and her family. Between 1833 and 1896, approximately 4 or 5 earthquakes were reported per year.[24]

Hawaii accounted for 7.3% of the United States' reported earthquakes with a magnitude 3.5 or greater from 1974 to 2003, with a total 1533 earthquakes. Hawaii ranked as the state with the third most earthquakes over this time period, after Alaska and California.[25]

On October 15, 2006, there was an earthquake with a magnitude of 6.7 off the northwest coast of the island of Hawaii, near the Kona area of the big island. The initial earthquake was followed approximately five minutes later by a magnitude 5.7 aftershock. Minor-to-moderate damage was reported on most of the Big Island. Several major roadways became impassable from rock slides, and effects were felt as far away as Honolulu, Oahu, nearly 150 miles (240 km) from the epicenter. Power outages lasted for several hours to days. Several water mains ruptured. No deaths or life-threatening injuries were reported.

On May 4, 2018 there was a 6.9 earthquake in the zone of volcanic activity from Kīlauea.

Earthquakes are monitored by the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory run by the USGS.

Tsunamis

The Hawaiian Islands are subject to tsunamis, great waves that strike the shore. Tsunamis are most often caused by earthquakes somewhere in the Pacific. The waves produced by the earthquakes travel at speeds of 400–500 miles per hour (600–800 km/h) and can affect coastal regions thousands of miles (kilometers) away.

Tsunamis may also originate from the Hawaiian Islands. Explosive volcanic activity can cause tsunamis. The island of Molokaʻi had a catastrophic collapse or debris avalanche over a million years ago; this underwater landslide likely caused tsunamis. The Hilina Slump on the island of Hawaiʻi is another potential place for a large landslide and resulting tsunami.

The city of Hilo on the Big Island has been most affected by tsunamis, where the in-rushing water is accentuated by the shape of Hilo Bay. Coastal cities have tsunami warning sirens.

A tsunami resulting from an earthquake in Chile hit the islands on February 27, 2010. It was relatively minor, but local emergency management officials utilized the latest technology and ordered evacuations in preparation for a possible major event. The Governor declared it a "good drill" for the next major event.

A tsunami resulting from an earthquake in Japan hit the islands on March 11, 2011. It was relatively minor, but local officials ordered evacuations in preparation for a possible major event. The tsunami caused about $30.1 million in damages.[26]

Ecology

The islands are home to a multitude of endemic species. Since human settlement, first by Polynesians, non native trees, plants, and animals were introduced. These included species such as rats and pigs, that have preyed on native birds and invertebrates that initially evolved in the absence of such predators. The growing population of humans has also led to deforestation, forest degradation, treeless grasslands, and environmental degradation. As a result, many species which depended on forest habitats and food became extinct—with many current species facing extinction. As humans cleared land for farming, monocultural crop production replaced multi-species systems.

The arrival of the Europeans had a more significant impact, with the promotion of large-scale single-species export agriculture and livestock grazing. This led to increased clearing of forests, and the development of towns, adding many more species to the list of extinct animals of the Hawaiian Islands. As of 2009, many of the remaining endemic species are considered endangered.[27]

National Monument

On June 15, 2006, President George W. Bush issued a public proclamation creating Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument under the Antiquities Act of 1906. The Monument encompasses the northwestern Hawaiian Islands and surrounding waters, forming the largest[28] marine wildlife reserve in the world. In August 2010, UNESCO's World Heritage Committee added Papahānaumokuākea to its list of World Heritage Sites.[29][30][31] On August 26, 2016, President Barack Obama greatly expanded Papahānaumokuākea, quadrupling it from its original size.[32][33][34]

Climate

The climate of the Hawaiian Islands is tropical but it experiences many different climates, depending on altitude and weather.[35] The islands receive most rainfall from the trade winds on their north and east flanks (the windward side) as a result of orographic precipitation.[35] Coastal areas in general and especially the south and west flanks or leeward sides, tend to be drier.[35]

In general, the lowlands of Hawaiian Islands receive most of their precipitation during the winter months (October to April).[35] Drier conditions generally prevail from May to September.[35] The tropical storms, and occasional hurricanes, tend to occur from July through November.[35]

During the summer months the average temperature is about 84 °F (29 °C), in the winter months it is approximately 78,8 °F (26°C). As the temperature is relatively constant over the year the probability of dangerous thunderstorms is approximately low.[36]

See also

References

- Macdonald, Abbott, and Peterson, 1984

- Pearce, Charles E.M.; Pearce, F. M. (2010). Oceanic Migration: Paths, Sequence, Timing and Range of Prehistoric Migration in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 167. ISBN 978-90-481-3826-5.

- Whittaker, Elvi W. (1986). The Mainland Haole: The White Experience in Hawaii. Columbia University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-231-05316-7.

- Rayson, Ann; Bauer, Helen (1997). Hawaii: The Pacific State. Bess Press. p. 26. ISBN 1573060968.

- James Cook and James King (1784). A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean: Undertaken, by the Command of His Majesty, for Making Discoveries in the Northern Hemisphere, to Determine the Position and Extent of the West Side of North America, Its Distance from Asia, and the Practicability of a Northern Passage to Europe: Performed Under the Direction of Captains Cook, Clerke, and Gore, in His Majesty's Ships the Resolution and Discovery, in the Years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779, and 1780. 2. Nicol and Cadell, London. p. 222.

- Clement, Russell. "From Cook to the 1840 Constitution: The Name Change from Sandwich to Hawaiian Islands" (PDF). University of Hawai'i at Manoa Hamilton Library. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- "Guide to State and Local Census Geography – Hawaii" (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. 2013-09-09. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- Blay, Chuck, and Siemers, Robert. Kauai‘’s Geologic History: A Simplified Guide. Kaua‘i: TEOK Investigations, 2004. ISBN 9780974472300. (Cited in "Hawaiian Encyclopedia : The Islands". Retrieved June 20, 2012.)

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Island of Hawaiʻi

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Maui Island

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Oʻahu Island

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kauaʻi Island

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Molokaʻi Island

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Lānaʻi Island

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Niʻihau Island

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Kahoʻolawe Island

- "Hawaii Population 2016 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 2016-09-12.

- "Hawaii : Image of the Day". nasa.gov. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "Hawai'i Facts & Figures" (PDF). state web site. State of Hawaii Dept. of Business, Economic Development & Tourism. December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-22. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "Tectonics, geochronology, and origin of the Hawaiian-Emperor Volcanic Chain" (PDF). The Geology of North America, Volume N: The Eastern Pacific Ocean and Hawaii. The Geology Society of America. 1989. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- McDougall, IAN; Swanson, D. A. (1972). "Potassium-Argon Ages of Lavas from the Hawi and Pololu Volcanic Series, Kohala Volcano, Hawaii". Geological Society of America Bulletin. Geology Society of American Bulletin. 83 (12): 3731–3738. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1972)83[3731:PAOLFT]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- "Petrography and K-Ar Ages of Dredged Volcanic Rocks from the Western Hawaiian Ridge and the Southern Emperor Seamount Chain". 86 (7). Geology Society of America Bulletin. 1975: 991–998. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1975)86. Retrieved 2011-01-17. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Mauna Loa Earth's Largest Volcano". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory web site. USGS. February 2006. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- "Hawaii Earthquake History". Earthquake Hazards Program. United States Geological Survey. 1972. Archived from the original on 2009-04-19. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- "Top Earthquake States". Earthquake Hazards Program. United States Geological Survey. 2003. Archived from the original on 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- Trusdell, Frank A.; Chadderton, Amy; Hinchliffe, Graham; Hara, Andrew; Patenge, Brent; Weber, Tom (2012-11-15). "Tohoku-Oki Earthquake Tsunami Runup and Inundation Data for Sites Around the Island of Hawai'i" (PDF). USGS. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- Craig R. Elevitch; Kim M. Wilkinson, eds. (2000). Agroforestry Guides for Pacific Islands. Permanent Agriculture Resources. ISBN 0-9702544-0-7. Archived from the original on 2006-01-12. Retrieved 2005-09-26.

- Barnett, Cynthia (August 26, 2016). "Hawaii Is Now Home to an Ocean Reserve Twice the Size of Texas". National Geographic. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- "21 sites added to Unesco World Heritage list – Wikinews, the free news source". en.wikinews.org. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Saltzstein, Dan (2010-08-04). "Unesco Adds 21 Sites to World Heritage List". New York Times. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- "World Heritage Committee inscribes a total of 21 new sites on UNESCO World Heritage List". whc.unesco.org. 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Cocke, Sophie (2016-08-25). "Obama expands Papahanaumokuakea marine reserve; plans Oahu trip". Honolulu Star Advertiser. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- "Fact Sheet: President Obama to Create the World's Largest Marine Protected Area". whitehouse.gov. 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Barnett, Cynthia (2016-08-26). "Hawaii Is Now Home to an Ocean Reserve Twice the Size of Texas". NationalGeographic.com. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- Lau, Leung-Ku Stephen; Mink, John Francis (2006-10-01). Hydrology of the Hawaiian Islands. pp. 39, 43, 49, 53. ISBN 9780824829483.

- "So ist das Wetter auf Hawaii". Hawaiiurlaub.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-06-24.

Further reading

- Morgan, Joseph R. (1996). "Hawai'i: A Unique Geography – Volcanic Landforms". Honolulu, HI: Bess Press. ISBN 1-57306-021-6. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - An integrated information website focused on the Hawaiian Archipelago from the Pacific Region Integrated Data Enterprise (PRIDE).

- Macdonald, G. A., A. T. Abbott, and F. L. Peterson. 1984. Volcanoes in the Sea: The Geology of Hawaii, 2nd edition. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. 517 pp.

- The Ocean Atlas of Hawai‘i – SOEST at University of Hawaiʻi.

- "Hawaiian Volcanoes – Introduction – Department of Geosciences". Corvallis, OR, USA. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2012.

Volcano World |; Your World is Erupting – Oregon State University College of Science