Pomerania

Pomerania (Polish: Pomorze; German: Pommern; Kashubian: Pòmòrskô) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The largest Pomeranian city is Gdańsk followed by Szczecin, both located in Poland. The region is particularly known for its Brick Gothic and resort architecture, the oddly-shaped Crooked Forest, the Pomeranian dog breed and one of the tallest lighthouses in the world.

Pomerania Pomorze, Pommern, Pòmòrskô | |

|---|---|

Historical region | |

Coat of arms | |

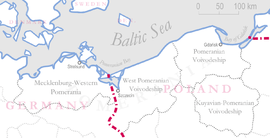

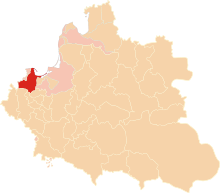

Contemporary administrative units with Pomerania in the name, not representing the exact historical region, as they also include parts of other regions | |

| Coordinates: 54.29°N 18.15°E | |

| Countries | |

| Largest cities | Gdańsk, Szczecin |

| Demonym(s) | Pomeranian |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Outside its urban areas, Pomerania is characterized by farmland, dotted with numerous lakes, forests, small picturesque towns and islands. The largest Pomeranian islands are Rügen, Usedom/Uznam and Wolin. The region has a rich and complicated political and demographic history, and was ruled by various countries, often simultaneously, including local dynasties, although over the centuries Polish and German influences remained the strongest. The region was heavily affected by numerous disastrous wars and border shifts since the Late Middle Ages, but also saw long periods of great prosperity, reflected in its rich architecture, mainly thanks to maritime trade. The easternmost sub-regions of Pomerania are alternatively known as Pomerelia and Kashubia, which are inhabited by ethnic Kashubians.

Geography

Borders

Pomerania is the area along the Bay of Pomerania of the Baltic Sea between the rivers Recknitz and Trebel in the west and Vistula in the east.[1][2] It formerly reached perhaps as far south as the Noteć river, but since the 13th century its southern boundary has been placed further north.

Landscape

Most of the region is coastal lowland, being part of the Central European Plain, but its southern, hilly parts belong to the Baltic Ridge, a belt of terminal moraines formed during the Pleistocene. Within this ridge, a chain of moraine-dammed lakes constitutes the Pomeranian Lake District. The soil is generally rather poor, sometimes sandy or marshy.[1]

The western coastline is jagged, with many peninsulas (such as Darß–Zingst) and islands (including Rügen, Usedom, and Wolin) enclosing numerous bays (Bodden) and lagoons (the biggest being the Lagoon of Szczecin).

The eastern coastline is smooth. Łebsko and several other lakes were formerly bays, but have been cut off from the sea. The easternmost coastline along the Gdańsk Bay (with the Bay of Puck) and Vistula Lagoon, has the Hel Peninsula and the Vistula peninsula jutting out into the Baltic.

Subregions

The Pomeranian region has the following administrative divisions:

- Hither Pomerania (Vorpommern) in northeastern Germany, stretching from the Recknitz river to the Oder–Neisse line. This region is part of the federal state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. The southernmost part of historical Vorpommern (the Gartz area) is now in Brandenburg, while its historical eastern parts (the Oder estuary) are now in Poland. Vorpommern comprises the historical regions inhabited by Western Slavic tribes Rugians and Volinians, otherwise the Principality of Rügen and the County of Gützkow.

- The West Pomeranian Voivodeship (Zachodniopomorskie) in Poland, stretching from the Oder–Neisse line to the Wieprza river, encompassing most of historical Pomerania in the narrow sense (as well as small parts of historic Greater Poland and Lubusz Land).

- The Pomeranian Voivodeship, with similar borders to Pomerelia, stretching from the Wieprza river to the Vistula delta in the vicinity of Gdańsk.

- The northern half of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, comprising most of Chełmno Land.

The bulk of Farther Pomerania is included within the modern West Pomeranian Voivodeship, but its easternmost parts (the Słupsk area) now constitute the northwest of Pomeranian Voivodeship. Farther Pomerania in turn comprises several other historical subregions, most notably the Principality of Cammin, the County of Naugard, the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp, and also the Lauenburg and Bütow Land (the last, however, is sometimes regarded as a part of Pomerelia or Kashubia).

Parts of Pomerania and surrounding regions have constituted a euroregion since 1995. The Pomerania euroregion comprises Hither Pomerania and Uckermark in Germany, West Pomerania in Poland, and Scania in Sweden.

.jpg) Typical Pomeranian beach (West Pomeranian Voivodeship)

Typical Pomeranian beach (West Pomeranian Voivodeship)

Etymology

"Pomerania" and its cognates in other languages are derived from Old Slavic po, meaning "by/next to/along", and morze, meaning "sea", thus "Pomerania" literally means "seacoast" or "land by the sea", referring to its proximity to the Baltic Sea.[3][1][2]

Pomerania was first mentioned in an imperial document of 1046, referring to a Zemuzil dux Bomeranorum (Zemuzil, Duke of the Pomeranians).[4] Pomerania is mentioned repeatedly in the chronicles of Adam of Bremen (c. 1070) and Gallus Anonymous (ca. 1113).

Terminology

The term "West Pomerania" is ambiguous, since it may refer to either Hither Pomerania (in German usage and historical usage based on German terminology[5]) or to combined Hither and Farther Pomerania or the West Pomeranian Voivodeship (in Polish usage).

The term "East Pomerania" may similarly carry different meanings, referring either to Farther Pomerania (in German usage and historical usage based on German terminology[5]), or to Pomerelia or the Pomeranian Voivodeship (in Polish usage).

| West | Pomerania | East | Southeast | |||||||||||

| Stralsund | Anklam | Szczecin |

Kołobrzeg |

Słupsk |

Gdynia |

Gdańsk |

Tczew | |||||||

| Current regions | Vorpommern (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern) |

Zachodniopomorskie (West Pomeranian Voivodeship) |

Pomeranian Voivodeship | |||||||||||

| German terminology (corresponding English term) |

Pommern[1] (Pomerania) |

Pomerellen, Pommerellen[1] (Pomerelia)[1] Westpreussen (West Prussia) | ||||||||||||

| Vorpommern in modern usage excluding Szczecin (Western Pomerania) (Hither Pomerania) |

Hinterpommern (Farther/Further Pomerania) Ostpommern (Eastern Pomerania) |

Kaschubei[6] (Kashubia) |

||||||||||||

| Polish terminology (corresponding English term) |

Pomorze Zachodnie (Western Pomerania) |

Pomorze Wschodnie (Eastern Pomerania) Pomorze Gdańskie (Gdańsk Pomerania) before World War II Pomorze[1] (Pomerelia,[1] literally Pomerania) | ||||||||||||

| Pomorze Przednie (Hither Pomerania) |

Pomorze Tylne (Farther/Further Pomerania) |

Kaszuby (Kashubia) ethnocultural region |

Kociewie ethnocultural region | |||||||||||

| Kashubian terminology (corresponding English term) |

Zôpadnô Pòmòrskô (Western Pomerania) |

Pòrénkòwô Pòmòrskô (Eastern Pomerania) | ||||||||||||

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Pomerania |

|

|

|

Prehistory to the Middle Ages (circa 400 A.D. – 1400 A.D.)

Settlement in the area called Pomerania for the last 1,000 years started by the end of the Vistula Glacial Stage, some 13,000 years ago.[7] Archeological traces have been found of various cultures during the Stone and Bronze Age, Baltic peoples, Germanic peoples and Veneti during the Iron Age and, in the Dark Ages, West Slavic tribes and Vikings.[8][9][10][7][11][12][13] Starting in the 10th century, early Polish rulers sudbued the region, successfully integrating the eastern part with Poland, while the western part fell under the suzerainty of Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire in the late 12th century.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20] Gdańsk, established during the reign of Mieszko I of Poland has since become Poland's main port (apart from periods of Poland losing control over the region).

In the 12th century, the Duchy of Pomerania (western part), as a vassal state of Poland, became Christian under saint Otto of Bamberg (the Apostle of the Pomeranians); at the same time Pomerelia (eastern part) became a part of diocese of Włocławek within Poland. Since the late 12th-early 13th century, the Griffin Duchy of Pomerania stayed with the Holy Roman Empire and the Principality of Rugia with Denmark, while Pomerelia, under the ruling of Samborides, was a part of Poland.[21][22][22][23][24] Pomerania, during its alliance in the Holy Roman Empire, shared borders with West Slavic state Oldenburg, as well as Poland and the expanding Margraviate of Brandenburg. In the early 14th century the Teutonic Knights invaded and annexed Pomerelia from Poland into their monastic state, which already included historical Prussia. As a result of the Teutonic rule, in German terminology the name of Prussia was also extended to conquered Polish lands like Gdańsk Pomerania, although it was not inhabited by Baltic Prussians but Lechitic Poles. Meanwhile, the Ostsiedlung started to turn Slavic narrow Pomerania into an increasingly German-settled area; the remaining Wends and Polish people, often known as Kashubians, continued to settle within Pomerelia.[25][26] In 1325 the line of the princes of Rügen died out, and the principality was inherited by the Griffins.[27]

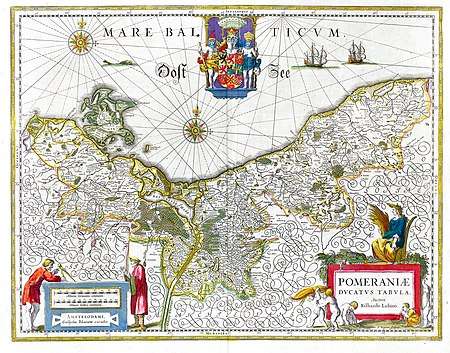

Renaissance (circa 1400–1700) to Early Modern Age

In 1466, with the Teutonic Order's defeat in the Thirteen Years' War, Pomerelia became again subject to the Polish Crown and formed the Pomeranian Voivodeship within the province of Royal Prussia.[28] While the German population in the Duchy of Pomerania adopted the Protestant reformation in 1534,[29][30][31] the Polish (along with Kashubian) population remained with the Roman Catholic Church. The Thirty Years' War severely ravaged and depopulated narrow Pomerania; few years later this same happened to Pomerelia (the Deluge).[32] With the extinction of the Griffin house during the same period, the Duchy of Pomerania was divided between the Swedish Empire and Brandenburg-Prussia in 1648, while Pomerelia remained in with the Polish Crown.

Modern Age

.svg.png)

Prussia gained the southern parts of Swedish Pomerania in 1720,[33]:341–343 invaded and annexed Pomerelia from Poland in 1772 and 1793, and gained the remainder of Swedish Pomerania in 1815, after the Napoleonic Wars.[33]:363, 364 The former Brandenburg-Prussian Pomerania and the former Swedish parts were reorganized into the Prussian Province of Pomerania,[33]:366 while Pomerelia was made part of the Province of West Prussia. With Prussia, both provinces joined the newly constituted German Empire in 1871. Under the German rule the Polish minority suffered discrimination and oppressive measures aimed at eradicating its culture. Following the empire's defeat in World War I, however, Pomorze Gdańskie/Pomerelia was returned to the rebuilt Polish state as part of the so-called Polish Corridor), while German-majority Gdansk/Danzig was transformed into the independent Free City of Danzig. Germany's Province of Pomerania was expanded in 1938 to include northern parts of the former Province of Posen–West Prussia, and in late 1939 the annexed Pomorze Gdańskie/Polish Corridor became part of the wartime Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia. The Nazis deported the Pomeranian Jews to a reservation near Lublin[34] in Pomerelia. The Polish population suffered heavily during the Nazi oppression; more than 40,000 died in executions, death camps, prisons and forced labour, primarily those who were teachers, businessmen, priests, politicians, former army officers, and civil servants.[35] Thousands of Poles and Kashubians suffered deportation, their homes taken over by the German military and civil servants, as well as some Baltic Germans resettled there between 1940-1943.

After Nazi Germany's defeat in World War II, the German–Polish border was shifted west to the Oder–Neisse line, and all of Pomerania was under Soviet military control.[33]:512–515[36]:373ff The German citizens of the former eastern territories of Germany and Poles of German ethnicity from Pomerelia were expelled, and the area was resettled primarily with Poles of Polish ethnicity, (some themselves expellees from former eastern Poland) and some Poles of Ukrainian ethnicity (resettled under Operation Vistula) and few Polish Jews.[36]:381ff[37][38] Most of Hither or Western Pomerania (Vorpommern) remained in Germany, and at first about 500,000 fled and expelled Farther Pomeranians found refuge there, later many moved on to other German regions and abroad. Today German Hither Pomerania forms the eastern part of the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, while the Polish part is divided mainly between the West Pomeranian, Pomeranian voivodeships, with their capitals in Szczecin and Gdańsk. During the 1980s, the Solidarity and Die Wende ("the change") movements overthrew the Communist regimes implemented during the post-war era; since then, Pomerania is democratically governed.

Pomerania still lives in the country of Brazil in a colony where the language is still spoken. The arrival of Pomerania immigrants with Germans and Italians helped form the state of Espírito Santo since the early 1930s.[39] Their importance and respect are one of the cultural signatures of the area. The Brazilian city of Pomerode (in the state of Santa Catarina) was founded by Pomeranian Germans in 1861 and is considered the most typically German of all the German towns of southern Brazil.

Demographics

Western Pomerania is inhabited by German Pomeranians. In the eastern parts, Poles are the dominating ethnic group since the territorial changes of Poland after World War II, and the resulting Polonization. Kashubians, descendants of the medieval West Slavic Pomeranians, are numerous in rural Pomerelia.

| Polish voivodeship/ German landschaft |

Capital | Registration plates |

Area (km²) |

Population Polish 31 December 1999 German December 2010 |

Territorial code |

| Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship (northern half) |

Bydgoszcz (Voivod office) Toruń (Voivod council) |

C | 17,969.72 | 2,100,771 | 04 |

| Pomeranian Voivodeship | Gdańsk | G | 18,292.88 | 2,192,268 | 22 |

| West Pomeranian Voivodeship | Szczecin | Z | 22,901.48 | 1,732,838 | 32 |

| Polish Pomerania and Kuyavia total | 59,164.08 | 6,025,877 | |||

| Vorpommern-Greifswald | Greifswald | VG and locally optional: ANK, GW, HGW, PW, SBG, UEM, WLG | 3,927 | 245,733 | |

| Vorpommern-Rügen | Stralsund | VR and locally optional: GMN, HST, NVP, RDG, and RÜG | 3,188 | 230,743 | |

| German Pomerania total | 7,115 | 476,476 | |||

Hither Pomerania

German Hither Pomerania had a population of about 470,000 in 2012 (districts of Vorpommern-Rügen and Vorpommern-Greifswald combined) - while the Polish districts of the region had a population of about 520,000 in 2012 (cities of Szczecin, Świnoujście and Police County combined). So overall, about 1 million people live in the historical region of Hither Pomerania today, while the Szczecin metropolitan area reaches even further.

Cities and towns with more than 50,000 inhabitants

Cities in the historical region of Pomerania (with population figures for 2012):

- Szczecin (West Pomeranian Voivodeship, 408,913; up to 763,321 in the metropolitan area[40])

- Stralsund-Greifswald high level urban center of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (population 113,128), including:

- Stralsund (57,357)

- Greifswald (Low German: Griepswohld) (55,771)

- Koszalin (West Pomeranian Voivodeship, 109,343)

- Słupsk (Pomeranian Voivodeship, 94,849)

- Stargard (West Pomeranian Voivodeship, 69,724)

Other cities in the Pomeranian and Kuyavian-Pomeranian voivodeships:

- Tricity metropolitan area (Pomeranian Voivodeship) (population in 2012: at least 1,035,000; area 1,332,51 km2), including:

- Wejherowo (50,375)

- Toruń (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, 205,934)

- Grudziądz (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, 96,042)

- Tczew (Pomeranian Voivodeship, 60,279)

Culture

Languages and dialects

In the German part of Pomerania, Standard German and the East Low German Mecklenburgisch-Vorpommersch and Central Pomeranian dialects are spoken, though Standard German dominates. Polish is the dominating language in the Polish part; Kashubian dialects are also spoken by the Kashubians in Pomerelia.

East Pomeranian, the East Low German dialect of Farther Pomerania and western Pomerelia, Low Prussian, the East Low German dialect of eastern Pomerelia, and Standard German were dominating in Pomerania east of the Oder-Neisse line before most of its speakers were expelled after World War II. Slovincian was spoken at the Farther Pomeranian–Pomerelian frontier, but is now extinct.

Kashubian and East Low German are also spoken by the descendants of émigrées, most notably in the Americas (e.g. Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Canada).

Cuisine

- For typical food and beverages of the region, see Pomeranian cuisine.

Museums

The Pomeranian State Museum in Greifswald, dedicated to the history of Pomerania, has a variety of archeological findings and artefacts from the different periods covered in this article. At least 50 museums in Poland cover the history of Pomerania, the most important of them being the National Museum in Gdańsk, the Central Pomerania Museum in Słupsk,[41] the Darłowo Museum,[42] the Koszalin Museum,[43] and the National Museum in Szczecin.[44]

Economy

Agriculture primarily consists of raising livestock, forestry, fishery, and the cultivation of cereals, sugar beets, and potatoes. Industrial food processing is increasingly relevant in the region. Key producing industries are shipyards, mechanical engineering facilities (i.a. renewable energy components), and sugar refineries, along with paper and wood fabricators.[1] Service industries today are an important economical factor in Pomerania, most notably with logistics, information technology, life science, biotechnology, health care, and other high-tech branches often clustering around research facilities of the Pomeranian universities.

Since the late 19th century, tourism has been an important sector of the economy, primarily in the numerous seaside resorts along the coast.

Gallery

Ruins of Augustinians' cloister in Jasienica, Police.

Ruins of Augustinians' cloister in Jasienica, Police..jpg) Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption in Pelplin, one of the largest churches in Poland

Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption in Pelplin, one of the largest churches in Poland

See also

- German exonyms (Pomorze)

- History of Pomerania

- Kashubian-Pomeranian Association

- Pomerania State Museum

- Pomeranian (dog)

- Pomerode

- Pomeranian (disambiguation)

Footnotes

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001-07 Archived August 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000, Pomerania

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000, Pomerania : "Pomerania is the medieval Latin form of German Pommern, itself a loanword in German from Old Slavic. The Polish word for Pomerania is Pomorze, composed of the preposition po, "along, by," and morze, "sea." The Slavic word for sea, more, which becomes morze in Polish, comes from the Indo-European noun *mori–, "sea," the source of Latin mare, "sea," and the mer- of English mermaid."

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.23,24, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- e.g. here (Sheperd Atlas), or in old Enc Britannica

- "Duden online Kaschubei". June 12, 2019.

- Johannes Hoops, Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, Walter de Gruyter, p.422, ISBN 3-11-017733-1

- From the First Humans to the Mesolithic Hunters in the Northern German Lowlands, Current Results and Trends - THOMAS TERBERGER. From: Across the western Baltic, edited by: Keld Møller Hansen & Kristoffer Buck Pedersen, 2006, ISBN 87-983097-5-7 OCLC 43087092, Sydsjællands Museums Publikationer Vol. 1 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-11. Retrieved 2008-10-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, pp.18ff, ISBN 83-906184-8-6

- Horst Wernicke, Greifswald, Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, pp.16ff, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- A. W. R. Whittle, Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p.198, ISBN 0-521-44920-0

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.22,23, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Joachim Herrmann, Die Slawen in Deutschland, Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1985, pp.pp.237ff,244ff

- Joachim Herrmann, Die Slawen in Deutschland, Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1985, pp.261,345ff

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.32, ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092:pagan reaction of 1005

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.25, ISBN 3-88680-272-8: pagan uprising that also ended the Polish suzerainty in 1005

- A. P. Vlasto, Entry of Slavs Christendom, CUP Archive, 1970, p.129, ISBN 0-521-07459-2: abandoned 1004 - 1005 in face of violent opposition

- Nora Berend, Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus' C. 900-1200, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p.293, ISBN 0-521-87616-8, ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2

- David Warner, Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg, Manchester University Press, 2001, p.358, ISBN 0-7190-4926-1, ISBN 978-0-7190-4926-2

- Michael Borgolte, Benjamin Scheller, Polen und Deutschland vor 1000 Jahren: Die Berliner Tagung über den "Akt von Gnesen", Akademie Verlag, 2002, p.282, ISBN 3-05-003749-0, ISBN 978-3-05-003749-3

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, pp.35ff, ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- Gerhard Krause, Horst Robert Balz, Gerhard Müller, Theologische Realenzyklopädie, Walter de Gruyter, 1997, pp.40ff, ISBN 3-11-015435-8

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.34ff,87,103, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Jan M. Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.43, ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, pp.77ff, ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.45ff, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.115,116, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, p.186, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.205–212, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Richard du Moulin Eckart, Geschichte der deutschen Universitäten, Georg Olms Verlag, 1976, pp.111,112, ISBN 3-487-06078-7

- Gerhard Krause, Horst Robert Balz, Gerhard Müller, Theologische Realenzyklopädie, Walter de Gruyter, 1997, pp.43ff, ISBN 3-11-015435-8

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.263,332,341–343,352–354, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- Leni Yahil, Ina Friedman, Haya Galai, The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932-1945, Oxford University Press US, 1991, ISBN 0-19-504523-8, p.138: February 12/13, 1940, 1,300 Jews of all sexes and ages, extreme cruelty, no food allowed to be taken along, cold, some died during deportation, cold and snow during resettlement, 230 dead by March 12, Lublin reservation chosen in winter, 30,000 Germans resettled before to make room

- "Poland". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- Tomasz Kamusella in Prauser and Reeds (eds), The Expulsion of the German communities from Eastern Europe, p.28, EUI HEC 2004/1 Archived 2009-10-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Philipp Ther, Ana Siljak, Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944-1948, 2001, p.114, ISBN 0-7425-1094-8, ISBN 978-0-7425-1094-4

- "Os pomeranos: um povo sem Estado finca suas raízes no Brasil" (in Portuguese).

- Entwicklungsprioritäten der Metropolregion Stettin Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine (German PDF; 1,7 MB)

- "Muzeum Pomorza Środkowego - Strona główna". Muzeum.slupsk.pl. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- "Muzeum w Darłowie - Zamek Książąt Pomorskich zaprasza". Muzeumdarlowo.pl. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- "Muzeum w Koszalinie". Muzeum.koszalin.pl. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- "Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie - Aktualności". Muzeum.szczecin.pl. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pomerania. |

Internet directories

Culture and history

- Pomeranian dukes castle in Szczecin (Polish, German, English)

- Pomeranian (German)

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Collection of historical eBooks about Pomerania (German)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)