Bengal

Bengal (/bɛŋˈɡɔːl/;[4] Bengali: বাংলা/বঙ্গ, romanized: Bānglā/Bôngô Bengali pronunciation: [bɔŋgo]) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. Geographically, it is made up by the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta system, the largest such formation in the world; along with mountains in its north bordering the Himalayan states of Nepal and Bhutan and east bordering Burma.

Bengal

| |

|---|---|

Region | |

| Continent | Asia |

| Countries | |

| Major cities | |

| Iron Age India, Vedic India, Vanga Kingdom | 1500 – c. 500 BCE |

| Gangaridai, Nanda Empire | 500 – c. 350 BCE |

| Mauryan Empire | 4th century–2nd century BCE |

| Shunga Empire, Gupta Empire, Later Gupta dynasty | 185 BCE–75 BCE, 3rd century CE–543 CE, 6th century–7th century |

| Pala Empire | 8th century–11th century |

| Sena Empire | 12th century |

| Delhi Sultanate, Bengal Sultanate | 1204–1339 CE, 1338–1576 CE |

| Bengal Subah (Mughal Empire), Nawabs of Bengal and Murshidabad | 1565–1717 CE, 1717–1765 CE |

| Bengal Presidency (British India) | 1765–1947 CE |

| Principal subdivisions | List

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 236,322.65 km2 (91,244.69 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | c. 253 Million[1] |

| • Density | 830/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Bengali |

| Official languages | Bangladesh – Bengali[2] West Bengal – Bengali[3] |

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

|

Bengali homeland |

|

Bengali culture

|

|

Bengali symbols |

Politically, Bengal is currently divided between Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. In 2011, the population of Bengal was estimated to be 250 million,[1] making it one of the most densely populated regions in the world.[5] Among them, an estimated 160 million people live in Bangladesh and 91.3 million people live in West Bengal. The predominant ethnolinguistic group is the Bengali people, who speak the Indo-Aryan Bengali language. Bengali Muslims are the majority in Bangladesh and Bengali Hindus are the majority in West Bengal. Outside this region, Indian states of Tripura and Assam's Barak Valley has a Bengali majority popualtion with significant presence in the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Uttarakhand.[6]

Dense woodlands, including hilly rainforests, cover Bengal's northern and eastern areas; while an elevated forested plateau covers its central area. Highest elevation point of this region is Sandakphu (3636 m; 11,930 ft), which is located in Darjeeling district of West Bengal. In the littoral southwest are the Sundarbans, the world's largest mangrove forest and home of the Bengal tiger. In the coastal southeast lies Cox's Bazar, the longest beach in the world at 125 km (78 mi).[7] The region has a monsoon climate, which the Bengali calendar divides into six seasons.

At times an independent regional empire, Bengal was a leading power in South Asia and later the Islamic East, with extensive trade networks. In antiquity, its kingdoms were known as seafaring nations. Bengal was known to the Greeks as Gangaridai, notable for mighty military power. It was described by Greek historians that Alexander the Great withdrew from India anticipating a counterattack from an alliance of Gangaridai.[8] Later writers noted merchant shipping links between Bengal and Roman Egypt. The Bengali Pala Empire was the last major Buddhist imperial power in the subcontinent,[9] founded in 750 and becoming the dominant power in the northern Indian subcontinent by the 9th century,[10][11] before being replaced by the Hindu Sena dynasty in the 12th century.[9]

Islam was introduced during the Pala Empire, through trade with the Abbasid Caliphate.[12] Following the formation of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century, Islam spread across the Bengal region. During the Islamic Bengal Sultanate, founded in 1352, Bengal was a major trading nation in the world and was often referred to by Europeans as the richest country to trade with.[13] The Khorasanis referred to the land as an "inferno full of gifts", due to its unbearable climate but abundance of wealth.[14] It was later absorbed into the Mughal Empire in 1576. Bengal Subah, described as the Paradise of the Nations,[15] was the empire's wealthiest province, and became a major global exporter,[16][17][18] a center of worldwide industries such as cotton textiles, silk,[19] and shipbuilding.[20] Its economy was worth 12% of the world's GDP,[21][22][23] a value bigger than the entirety of Western Europe, and its citizens' living standards were among the world's highest.[24][21] Bengal's economy underwent a period of proto-industrialization during this period.[25]

The Maratha invasions of Bengal badly affected the economy of Bengal and it is estimated that 400,000 Bengalis were killed by the Maratha bargis,[26] and the genocide has been considered to be among the deadliest massacres in Indian history.[27]

Subsequently, the region was conquered by the British East India Company after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and became the Bengal Presidency of the British Raj. Bengal made significant contributions to the world's first Industrial Revolution, but experienced its own deindustrialisation.[28] The East India Company increased agriculture tax rates from 10% to up to 50%, which caused multiple famines such as the Great Bengal famine of 1770 which caused the death of 10 million Bengalis and the Bengal famine of 1943 which killed millions.

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups were dominant. Armed attempts to overthrow the British Raj began with the Sannyasi and Fakir Rebellion, and reached a climax when Subhas Chandra Bose led the Indian National Army allied with Japan to fight against the British. Many Bengalis died in the independence struggle and many were exiled in Cellular Jail, located in Andaman. The United Kingdom Cabinet Mission of 1946 split the region between India and Pakistan, an action popularly known as the partition of Bengal (1947). This was opposed by the Prime Minister of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, and nationalist leader Sarat Chandra Bose. They campaigned for a united and independent nation-state of Bengal. The initiative failed owing to British diplomacy and communal conflict between Muslims and Hindus.[note 1] Subsequently, Pakistan ruled East Bengal which later became the independent nation of Bangladesh by the Bangladesh War of Independence in 1971.

Etymology

The name of Bengal is derived from the ancient kingdom of Banga,(pronounced Bôngô)[29][30] the earliest records of which date back to the Mahabharata epic in the first millennium BCE.[30] The exact origin of the word Bangla is unknown. In Islamic mythology, it is said to come from "Bung/Bang", a son of Hind (son of Hām who was a son of Noah) who colonised the area for the first time.[31] The suffix "al" came to be added to it from the fact that the ancient rajahs of this land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al". From this suffix added to the Bung, the name Bengal arose and gained currency".[32][33] This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim's Riyaz-us-Salatin.[31]

Other theories on the origin of the term Banga point to the Proto-Dravidian Bong tribe that settled in the area circa 1000 BCE and the Austric word Bong (Sun-god).[34] The term Vangaladesa is used to describe the region in 11th-century South Indian records.[35][36][37] The Portuguese referred to the region as Bengala in the Age of Discovery.[38]

Geography

Most of the Bengal region lies in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, but there are highlands in its north, northeast and southeast. The Ganges Delta arises from the confluence of the rivers Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers and their respective tributaries. The total area of Bengal is 232,752 km2—West Bengal is 88,752 km2 (34,267 sq mi) and Bangladesh 147,570 km2 (56,977 sq mi).

The flat and fertile Bangladesh Plain dominates the geography of Bangladesh. The Chittagong Hill Tracts and Sylhet regions are home to most of the mountains in Bangladesh. Most parts of Bangladesh are within 10 metres (33 feet) above the sea level, and it is believed that about 10% of the land would be flooded if the sea level were to rise by 1 metre (3.3 feet).[39] Because of this low elevation, much of this region is exceptionally vulnerable to seasonal flooding due to monsoons. The highest point in Bangladesh is in Mowdok range at 1,052 metres (3,451 feet).[40] A major part of the coastline comprises a marshy jungle, the Sundarbans, the largest mangrove forest in the world and home to diverse flora and fauna, including the royal Bengal tiger. In 1997, this region was declared endangered.[41]

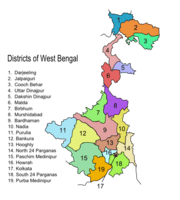

West Bengal is on the eastern bottleneck of India, stretching from the Himalayas in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the south. The state has a total area of 88,752 km2 (34,267 sq mi).[42] The Darjeeling Himalayan hill region in the northern extreme of the state belongs to the eastern Himalaya. This region contains Sandakfu (3,636 m (11,929 ft))—the highest peak of the state.[43] The narrow Terai region separates this region from the plains, which in turn transitions into the Ganges delta towards the south. The Rarh region intervenes between the Ganges delta in the east and the western plateau and high lands. A small coastal region is on the extreme south, while the Sundarbans mangrove forests form a remarkable geographical landmark at the Ganges delta.

At least nine districts in West Bengal and 42 districts in Bangladesh have arsenic levels in groundwater above the World Health Organization maximum permissible limit of 50 µg/L or 50 parts per billion and the untreated water is unfit for human consumption.[44] The water causes arsenicosis, skin cancer and various other complications in the body.

- Landscapes

.jpg) A river in Bangladesh

A river in Bangladesh.jpg) A mustard and date palm farm in West Bengal

A mustard and date palm farm in West Bengal A tea garden in Bangladesh

A tea garden in Bangladesh

Geographic distinctions

North Bengal

North Bengal is a term used for the north-western part of Bangladesh and northern part of West Bengal. The Bangladeshi part comprises Rajshahi Division and Rangpur Division. Generally, it is the area lying west of Jamuna River and north of Padma River, and includes the Barind Tract. Politically, West Bengal's part comprises Jalpaiguri Division (Alipurduar, Cooch Behar, Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, North Dinajpur, South Dinajpur and Malda) together and Bihar's parts include Kishanganj district. Darjeeling Hills are also part of North Bengal. Although only people of Jaipaiguri, Alipurduar and Cooch Behar identifies themselves as North Bengali. North Bengal is divided into Terai and Dooars regions. North Bengal is also noted for its rich cultural heritage, including two UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Aside from the Bengali majority, North Bengal is home to many other communities including Nepalis, Santhal people, Lepchas and Rajbongshis.

Northeast Bengal

Northeast Bengal[45] refers to the Sylhet region, comprising Sylhet Division of Bangladesh and the Karimganj district in the Indian state of Assam. The region is noted for its distinctive fertile highland terrain, extensive tea plantations, rainforests and wetlands. The Surma and Barak river are the geographic markers of the area. The city of Sylhet is its largest urban center, and the region is known for its unique language. The ancient name of the region is Srihatta.[46] The region was ruled by the Kamarupa and Harikela kingdoms as well as the Bengal Sultanate. It later became a district of the Mughal Empire. Alongside the predominant Bengali population resides a small Bishnupriya Manipuri, Khasia and other tribal minorities.[46]

The region is the crossroads of Bengal and northeast India.

Central Bengal

Central Bengal refers to the Dhaka Division of Bangladesh. It includes the elevated Madhupur tract with a large Sal tree forest. The Padma River cuts through the southern part of the region, separating the greater Faridpur region. In the north lies the greater Mymensingh and Tangail regions.

South Bengal

South Bengal covers the southern part of the Indian state of West Bengal and southwestern Bangladesh. The Indian part of South Bengal includes 12 districts: Kolkata, Howrah, Hooghly, Burdwan, East Midnapur, West Midnapur, Purulia, Bankura, Birbhum, Nadia, South 24 Parganas, North 24 Parganas.[47][48][49] The Bangladeshi part includes the proposed Faridpur Division, Khulna Division and Barisal Division.[50]

The Sundarbans, a major biodiversity hotspot, is located in South Bengal. Bangladesh hosts 60% of the forest, with the remainder in India.

Southeast Bengal

Southeast Bengal[51][52][53] refers to the hilly and coastal Bengali-speaking areas of Chittagong Division in southeastern Bangladesh. Southeast Bengal is noted for its thalassocratic and seafaring heritage. The area was dominated by the Bengali Harikela and Samatata kingdoms in antiquity. It was known to Arab traders as Harkand in the 9th century.[54] During the medieval period, the region was ruled by the Sultanate of Bengal, the Kingdom of Tripura, the Kingdom of Mrauk U, the Portuguese Empire and the Mughal Empire, prior to the advent of British rule. The Chittagonian dialect of Bengali is prevalent in coastal areas of southeast Bengal. Along with its Bengali population, it is also home to Tibeto-Burman ethnic groups, including the Chakma, Marma, Tanchangya and Bawm peoples.

Southeast Bengal is considered a bridge to Southeast Asia and the northern parts of Arakan are also historically considered to be a part of it.[55]

Places of interest

There are four World Heritage Sites in the region, including the Sundarbans, the Somapura Mahavihara, the Mosque City of Bagerhat and the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Other prominent places include the Bishnupur, Bankura temple city, the Adina Mosque, the Caravanserai Mosque, numerous zamindar palaces (like Ahsan Manzil and Cooch Behar Palace), the Lalbagh Fort, the Great Caravanserai ruins, the Shaista Khan Caravanserai ruins, the Kolkata Victoria Memorial, the Dhaka Parliament Building, archaeologically excavated ancient fort cities in Mahasthangarh, Mainamati, Chandraketugarh and Wari-Bateshwar, the Jaldapara National Park, the Lawachara National Park, the Teknaf Game Reserve and the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

Cox's Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh is home to the longest natural sea beach in the world with an unbroken length of 120 km (75 mi). It is also a growing surfing destination.[56] St. Martin's Island, off the coast of Chittagong Division, is home to the sole coral reef in Bengal.

Flora and fauna

The flat Bengal Plain, which covers most of Bangladesh and West Bengal, is one of the most fertile areas on Earth, with lush vegetation and farmland dominating its landscape. Bengali villages are buried among groves of mango, jack fruit, betel nut and date palm. Rice, jute, mustard and sugarcane plantations are a common sight. Water bodies and wetlands provide a habitat for many aquatic plants in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta. The northern part of the region features Himalayan foothills (Dooars) with densely wooded Sal and other tropical evergreen trees. Above an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), the forest becomes predominantly subtropical, with a predominance of temperate-forest trees such as oaks, conifers and rhododendrons. Sal woodland is also found across central Bangladesh, particularly in the Bhawal National Park. The Lawachara National Park is a rainforest in northeastern Bangladesh. The Chittagong Hill Tracts in southeastern Bangladesh is noted for its high degree of biodiversity.

The littoral Sundarbans in the southwestern part of Bengal is the largest mangrove forest in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The region has over 89 species of mammals, 628 species of birds and numerous species of fish. For Bangladesh, the water lily, the oriental magpie-robin, the hilsa and mango tree are national symbols. For West Bengal, the white-throated kingfisher, the chatim tree and the night-flowering jasmine are state symbols. The Bengal tiger is the national animal of Bangladesh and India. The fishing cat is the state animal of West Bengal.

History

Prehistory

Human settlement in Bengal can be traced back 20,000 years. Remnants of Copper Age settlements date back 4,300 years.[58][59] Archaeological evidence confirms that by the second millennium BCE, rice-cultivating communities inhabited the region. By the 11th century BCE, the people of the area lived in systemically-aligned housing, used human cemeteries and manufactured copper ornaments and fine black and red pottery.[60] The Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers were natural arteries for communication and transportation.[60] Estuaries on the Bay of Bengal allowed for maritime trade. The early Iron Age saw the development of metal weaponry, coinage, permanent field agriculture and irrigation.[60] From 600 BCE, the second wave of urbanisation engulfed the north Indian subcontinent, as part of the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.

Antiquity

Ancient Bengal was divided between the regions of Varendra, Suhma, Anga, Vanga, Samatata and Harikela. Early Indian literature described the region as a thalassocracy, with colonies in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.[61] For example, the first recorded king of Sri Lanka was a Bengali prince called Vijaya. The region was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans as Gangaridai.[62] The Greek ambassador Megasthenes chronicled its military strength and dominance of the Ganges delta. The invasion army of Alexander the Great was deterred by the accounts of Gangaridai's power in 325 BCE. Later Roman accounts noted maritime trade routes with Bengal. A Roman amphora has been found in Purba Medinipur district of West Bengal, made in Aelana (present day Aqaba in Jordan) between the 4th and 7th centuries AD.[63] Another prominent kingdom in Ancient Bengal was Pundravardhana which was located in Northern Bengal with its capital being located in modern-day Bogra, the kingdom was prominently buddhist leaving behind historic Viharas such as Mahasthangarh.[64][65][66] In vedic mythology the royal families of Magadha, Anga, Vanga, Suhma and Kalinga were all related and descended from one King.[67]

Ancient Bengal was considered a part of Magadha region, which was the cradle of Indian arts and sciences. Currently the Maghada region is divided into several states that are Bihar, Jharkhand and Bengal (West Bengal and East Bengal)[67] The legacy of Magadha includes the concept of zero, the invention of Chess[68] and the theory of solar and lunar eclipses and the Earth orbiting the Sun. Sanskrit and derived Old Indo-Aryan dialects, was spoken across Bengal.[69] The Bengali language evolved from Old Indo-Aryan Sanskrit dialects. The region was ruled by Hindu, Buddhist and Jain dynasties, including the Mauryans, Guptas, Varmans, Khadgas, Palas, Chandras and Senas among others. In the 9th century, Arab Muslim traders frequented Bengali seaports and found the region to be a thriving seafaring kingdom with well-developed coinage and banking.[60]

Medieval era

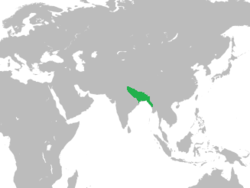

The Pala Empire was an imperial power in the Indian subcontinent, which originated in the region of Bengal. They were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism. The empire was founded with the election of Gopala as the emperor of Gauda in 750.[10] At its height in the early 9th century, the Pala Empire was the dominant power in the northern subcontinent, with its territory stretching across parts of modern-day eastern Pakistan, northern and northeastern India, Nepal and Bangladesh.[10][11] The empire enjoyed relations with the Srivijaya Empire, the Tibetan Empire, and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade between Bengal and the Middle East.[12] The resurgent Hindu Sena dynasty dethroned the Pala Empire in the 12th century, ending the reign of the last major Buddhist imperial power in the subcontinent.[9][70]

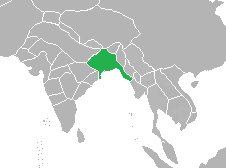

Muslim conquests of the Indian subcontinent absorbed Bengal in 1204.[71][72] The region was annexed by the Delhi Sultanate. Muslim rule introduced agrarian reform, a new calendar and Sufism. The region saw the rise of important city states in Sonargaon, Satgaon and Lakhnauti. By 1352, Ilyas Shah achieved the unification of an independent Bengal. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Bengal Sultanate was a major diplomatic, economic and military power in the subcontinent. It developed the subcontinent's relations with China, Egypt, the Timurid Empire and East Africa. In 1540, Sher Shah Suri was crowned Emperor of the northern subcontinent in the Bengali capital Gaur.

Mughal era (1576–1757)

The Mughal Empire conquered Bengal in the 16th century. The Bengal Subah province in the Mughal Empire was the wealthiest state in the subcontinent. Bengal's trade and wealth impressed the Mughals so much that it was described as the Paradise of the Nations by the Mughal Emperors.[73] The region was also notable for its powerful semi-independent aristocracy, including the Twelve Bhuiyans and the Nawabs of Bengal.[74] It was visited by several world explorers, including Ibn Battuta, Niccolo De Conti and Admiral Zheng He.

Under Mughal rule, Bengal was a center of the worldwide muslin and silk trades. During the Mughal era, the most important center of cotton production was Bengal, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka, leading to muslin being called "daka" in distant markets such as Central Asia.[19] Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles. Overseas, Europeans depended on Bengali products such as cotton textiles, silks and opium; Bengal accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia, for example, including more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks.[16] From Bengal, saltpetre was also shipped to Europe, opium was sold in Indonesia, raw silk was exported to Japan and the Netherlands, cotton and silk textiles were exported to Europe, Indonesia, and Japan,[17] cotton cloth was exported to the Americas and the Indian Ocean.[18] Bengal also had a large shipbuilding industry. In terms of shipbuilding tonnage during the 16th–18th centuries, economic historian Indrajit Ray estimates the annual output of Bengal at 223,250 tons, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[20]

Since the 16th century, European traders traversed the sea routes to Bengal, following the Portuguese conquests of Malacca and Goa. The Portuguese established a settlement in Chittagong with permission from the Bengal Sultanate in 1528, but were later expelled by the Mughals in 1666. In the 18th-century, the Mughal Court rapidly disintegrated due to Nader Shah's invasion and internal rebellions, allowing European colonial powers to set up trading posts across the territory. The British East India Company eventually emerged as the foremost military power in the region; and defeated the last independent Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757.[74]

Maratha Empire

The Maratha invasions of Bengal badly affected the economy of Bengal and it is estimated that 400,000 Bengali Hindus in western Bengal were killed by the Hindu Maratha bargis, and many women and children gang raped.,[26] and the genocide has been considered to be among the deadliest massacres in Indian history.[27]

Colonial era (1757–1947)

In Bengal effective political and military power was transferred from the old regime to the British East India Company around 1757–65.[75] Company rule in India began under the Bengal Presidency. Calcutta was named the capital of British India in 1772. The presidency was run by a military-civil administration, including the Bengal Army, and had the world's sixth earliest railway network. Great Bengal famines struck several times during colonial rule (notably the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and Bengal famine of 1943).[76][77]

About 50 million were killed in Bengal due to massive plague outbreaks and famines which happened in 1895 to 1920, mostly in western Bengal.[78]

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was initiated on the outskirts of Calcutta, and spread to Dhaka, Chittagong, Jalpaiguri, Sylhet and Agartala, in solidarity with revolts in North India. The failure of the rebellion led to the abolishment of the Mughal Court and direct rule by the British Raj. The late 19th and early 20th century Bengal Renaissance had a great impact on the cultural and economic life of Bengal and started a great advance in the literature and science of Bengal. Between 1905 and 1912, an abortive attempt was made to divide the province of Bengal into two zones, that included the short-lived province of Eastern Bengal and Assam based in Dacca and Shillong.[79] Under British rule, Bengal experienced deindustrialisation.[28] m

In 1876, about 200,000 people were killed in Bengal by the Great Bangladesh cyclone.[80]

Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups were dominant. Armed attempts to overthrow the British Raj began with the rebellion of Titumir, and reached a climax when Subhas Chandra Bose led the Indian National Army against the British. Bengal was also central in the rising political awareness of the Muslim population—the All-India Muslim League was established in Dhaka in 1906. The Muslim homeland movement pushed for a sovereign state in eastern British India with the Lahore Resolution in 1943. Hindu nationalism was also strong in Bengal, which was home to groups like the Hindu Mahasabha. In spite of a last-ditch effort to form a United Bengal,[81] when India gained independence in 1947, Bengal was partitioned along religious lines.[82] The western part went to India (and was named West Bengal) while the eastern part joined Pakistan as a province called East Bengal (later renamed East Pakistan, giving rise to Bangladesh in 1971). The circumstances of partition were bloody, with widespread religious riots in Bengal.[82][83]

The 1970 Bhola cyclone took the lives of 500,000 people in Bengal, making it one of the deadliest recorded cyclones.

Post-partition (1947–present)

India

- West Bengal

West Bengal became one of India's most populous states. Calcutta, the former capital of the British Raj, became the state capital of West Bengal and continued to be India's largest city until the late 20th century, when severe power shortages, strikes and a violent Marxist-Naxalite movement damaged much of the state's infrastructure in the 1960s and 70s, leading to a period of economic stagnation. West Bengal politics underwent a major change when the Left Front won the 1977 assembly election, defeating the incumbent Indian National Congress. The Left Front, led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)) governed the state for over three decades, which was the world's longest elected Communist administration in history.[84] Since the 2000s, West Bengal has experienced an economic rejuvenation, particularly in its IT industry.

- Tripura

The princely state of Hill Tippera, that was under the suzerainty of British India. Following the death of Maharaja Bir Bikram Kishore Debbarman, the princely state acceded to the Union of India on 15 October 1949 under the Tripura Merger Agreement signed by Maharani Regent Kanchan Prava Devi. By the 1950s, the region had a Bengali majority population due to the influx of Hindu refugees from East Pakistan after partition. It became a Union Territory of India in November 1953. It was granted full statehood with an elected legislature in July 1963. An insurgency by indigenous people affected the state for several years. The Left Front ruled the state between 1978 and 1988, followed by a stint of Indian National Congress rule until 1993, and then a return to the Communists.[85]

- Barak Valley of Assam

Karimganj District joined the union of India after its partition from Sylhet as per Sylhet referendum in 1947 and has been a part of the state of Assam's Barak Valley. One of the most significant events in the region's history was the language movement in 1961, in which the killing of agitators by state police led to Bengali being recognised as one of the official languages of Assam. The issue of Bengali settlement in the state has been a contentious part of the Assam conflict.

Bangladesh

East Pakistan (1947–1971)

In 1948, the Government of the Dominion of Pakistan ordained Urdu as the sole national language, sparking extensive protests among the Bengali-speaking majority of East Bengal. Facing rising sectarian tensions and mass discontent with the new law, the government outlawed public meetings and rallies. The students of the University of Dhaka and other political activists defied the law and organised a protest on 21 February 1952. The movement reached its climax when several student demonstrators were shot dead by police firing. As a result of the movement, Pakistan government in 1956 included Bengali as national lanuage along with Urdu. UNESCO in 1999 declared 21 February as International Mother Language Day honouring the 1952 incident.

East Bengal, which was later renamed to East Pakistan in 1955, was home to Pakistan's demographic majority and played an instrumental role in the founding of the new state. Strategically, Pakistan joined the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization under the Bengali prime minister Mohammad Ali of Bogra as a bulwark against communism.[86] However, tensions between East and West Pakistan grew rapidly over political exclusion, economic neglect and ethnic and linguistic discrimination. The State of Pakistan was subjected to years of military rule due to fears of Bengali political supremacy under democracy. Elected Bengali-led governments at the federal and provincial levels, which were led by statesmen such as A. K. Fazlul Huq and H. S. Suhrawardy, were deposed.[87][88]

East Pakistan witnessed the rise of Bengali self determination calls led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Maulana Bhashani in the 1960s.[89] Rahman launched the Six point movement for autonomy in 1966. After the 1970 national election, Rahman's party, the Awami League, had emerged as the largest party in Pakistan's parliament. The erstwhile Pakistani military junta refused to accept election results which triggered civil disobedience across East Pakistan. The Pakistani military responded by launching a genocide that caused the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. The first Government of Bangladesh and the Mukti Bahini waged a guerrilla campaign with support from neighbouring India, which hosted millions of war refugees. Global support for the independence of East Pakistan increased due to the conflict's humanitarian crisis, with the Indian Armed Forces intervening in support of the Bangladesh Forces in the final two weeks of the war and ensuring Pakistan's surrender.[90]

Bangladesh (1971–present)

After independence, Bangladesh adopted a secular democracy under its new constitution in 1972. Awami League premier Sheikh Mujibur Rahman became the country's strongman and implemented many socialist policies. A one party state was enacted in 1975. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated later that year during a military coup that ushered in sixteen years of military dictatorships and presidential governments. The liberation war commander Ziaur Rahman emerged as Bangladesh's leader in the late 1970s. He reoriented the country's foreign policy towards the West and restored free markets and the multiparty polity. President Zia was assassinated in 1981 during a failed military coup. He was eventually succeeded by his army chief Hussain Muhammad Ershad. Lasting for nine years, Ershad's rule witnessed continued pro-free market reforms and the devolution of some authority to local government.[91] The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was founded in Dhaka in 1985.[92] The Jatiya Party government made Islam the state religion in 1988.[93]

A popular uprising restored parliamentary democracy in 1991. Since then, Bangladesh has largely alternated between the premierships of Sheikh Hasina of the Awami League and Khaleda Zia of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, as well as technocratic caretaker governments. Emergency rule was imposed by the military in 2007 and 2008 after widespread street violence between the League and BNP. The restoration of democratic government in 2009 was followed by the initiation of the International Crimes Tribunal to prosecute surviving collaborators of the 1971 genocide. Today, the country is one of the emerging and growth-leading economies of the world. It is listed as one of the Next Eleven countries, it also has one of the fastest real GDP growth rates. Its gross domestic product ranks 39th largest in the world in terms of market exchange rates and 30th in purchasing power parity. Its per capita income ranks 143th and 136th in two measures. In the field of human development, it has progressed ahead in life expectancy, maternal and child health, and gender equality. But it continues to face challenging problems, including poverty, corruption, terrorism, illiteracy, and inadequate public healthcare.[94][95]

Historical maps and flags of states

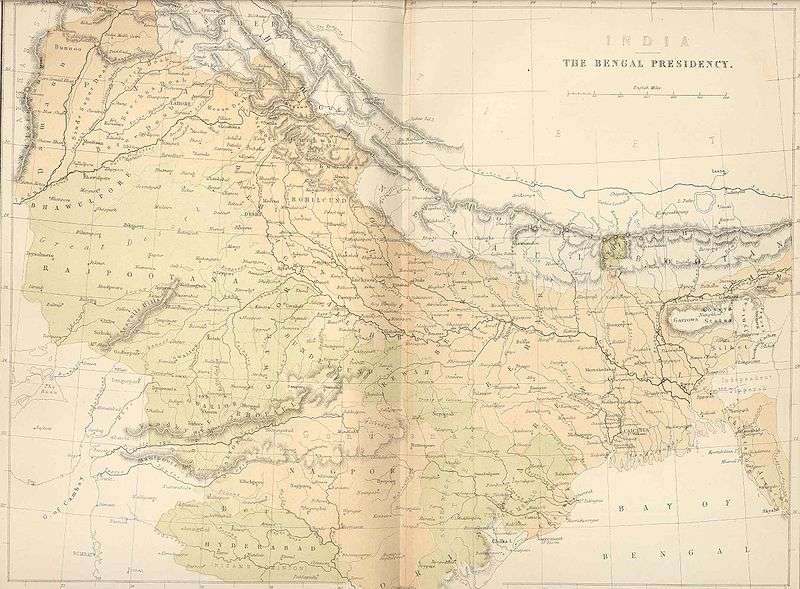

The Bengal region had been part of major empires and kingdoms like Gangaridai, Nanda Empire, Maurya Empire, Gupta Empire, Pala Empire, Sena dynasty, and Bengal Sultanate. It has also been a regional empire, ruling over neighbouring regions like Bihar, Orissa, Arakan, and parts of North India, Assam and Nepal.

Maps

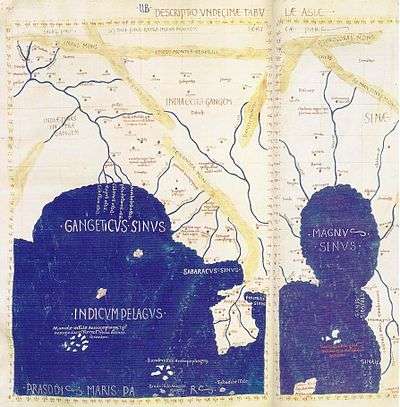

Gangaridai in Ptolemy's map, 1st century

Gangaridai in Ptolemy's map, 1st century The Pala Empire, 9th century

The Pala Empire, 9th century At its greatest extent, the Bengal Sultanate's realm and protectorates stretched from Jaunpur in North India in the west to Tripura and Arakan in the east

At its greatest extent, the Bengal Sultanate's realm and protectorates stretched from Jaunpur in North India in the west to Tripura and Arakan in the east The Bengal Sultanate, 16th century

The Bengal Sultanate, 16th century Bengal & Bihar in 1776 by James Rennell

Bengal & Bihar in 1776 by James Rennell Colonial Bengal, 19th century

Colonial Bengal, 19th century Colonial Eastern Bengal and Assam, early 20th century

Colonial Eastern Bengal and Assam, early 20th century Map of West Bengal

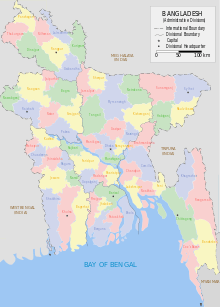

Map of West Bengal Map of Bangladesh

Map of Bangladesh

Flags

Flag of Bengal Sultanate

Flag of Bengal Sultanate.svg.png) Flag of the Bengal Subah (15-18th Century)

Flag of the Bengal Subah (15-18th Century) Flag of Bengal Presidency, under British rule

Flag of Bengal Presidency, under British rule Flag of Bangladesh during Bangladesh Liberation War

Flag of Bangladesh during Bangladesh Liberation War Flag of Bangladesh

Flag of Bangladesh

Politics

Politically, the region is divided between the People's Republic of Bangladesh, an independent state, and the eastern provinces of the Republic of India, including West Bengal. Politically both Bangladesh and Indian Bengal are socialist, with left wing parties dominating the region's politics.

Bangladeshi Republic

The state of Bangladesh is a parliamentary republic based on the Westminster system, with a written constitution and a President elected by parliament for mostly ceremonial purposes. The government is headed by a Prime Minister, who is appointed by the President from among the popularly elected 300 Members of Parliament in the Jatiyo Sangshad, the national parliament. The Prime Minister is traditionally the leader of the single largest party in the Jatiyo Sangshad. Under the constitution, while recognising Islam as the country's established religion, the constitution grants freedom of religion to non-Muslims.

Between 1975 and 1990, Bangladesh had a presidential system of government. Since the 1990s, it was administered by non-political technocratic caretaker governments on four occasions, the last being under military-backed emergency rule in 2007 and 2008. The Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) are the two largest political parties in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is a member of the UN, WTO, IMF, the World Bank, ADB, OIC, IDB, SAARC, BIMSTEC and the IMCTC. Bangladesh has achieved significant strides in human development compared to its neighbours.

Indian Bengal

West Bengal are provincial states of the Republic of India, with local executives and assemblies- features shared with other states in the Indian federal system. The president of India appoints a governor as the ceremonial representative of the union government. The governor appoints the chief minister on the nomination of the legislative assembly. The chief minister is the traditionally the leader of the party or coalition with most seats in the assembly. President's rule is often imposed in Indian states as a direct intervention of the union government led by the prime minister of India.

Each state has popularly elected members in the Indian lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha. Each state nominates members to the Indian upper house of parliament, the Rajya Sabha.

The state legislative assemblies also play a key role in electing the ceremonial president of India. The former president of India, Pranab Mukherjee, was a native of West Bengal and a leader of the Indian National Congress.

The two major political forces in the Bengali-speaking zone of India are the Left Front and the Trinamool Congress, with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress being minor players.

Crossborder relations

India and Bangladesh are the world's second and eighth most populous countries respectively. Bangladesh-India relations began on a high note in 1971 when India played a major role in the liberation of Bangladesh, with the Indian Bengali populace and media providing overwhelming support to the independence movement in the former East Pakistan. The two countries had a twenty five-year friendship treaty between 1972 and 1996. However, differences over river sharing, border security and access to trade have long plagued the relationship. In more recent years, a consensus has evolved in both countries on the importance of developing good relations, as well as a strategic partnership in South Asia and beyond. Commercial, cultural and defence co-operation have expanded since 2010, when Prime Ministers Sheikh Hasina and Manmohan Singh pledged to reinvigorate ties.

The Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi operates a Deputy High Commission in Kolkata and a consular office in Agartala. India has a High Commission in Dhaka with consulates in Chittagong and Rajshahi. Frequent international air, bus and rail services connect major cities in Bangladesh and Indian Bengal, particularly the three largest cities- Dhaka, Kolkata and Chittagong. Undocumented immigration of Bangladeshi workers is a controversial issue championed by right-wing nationalist parties in India but finds little sympathy in West Bengal.[96] India has since fenced the border which has been criticised by Bangladesh.[97]

Demographics

Religions in Bengal region (Bangladesh and West Bengal) 2011

The Bengal region is one of the most densely populated areas in the world. With a population of 300 million, Bengalis are the third largest ethnic group in the world after the Han Chinese and Arabs.[note 2] According to provisional results of 2011 Bangladesh census, the population of Bangladesh was 149,772,364;[98] however, CIA's The World Factbook gives 163,654,860 as its population in a July 2013 estimate. According to the provisional results of the 2011 Indian national census, West Bengal has a population of 91,347,736.[99] So, the Bengal region, as of 2011, has at least 241.1 million people, out of which 158.8 million are Muslims (66.4%), 77 million are Hindus (32%) and 5.3 million (1.6%) are others particularly (Buddhists, Christians Animists etc). This figures give a population density of 1003.9/km2; making it among the most densely populated areas in the world.[100][101]

Bengali is the main language spoken in Bengal. Many phonological, lexical, and structural differences from the standard variety occur in peripheral varieties of Bengali; these include Sylheti, Chittagonian, Chakma, Rangpuri/Rajbangshi, Hajong, Rohingya, and Tangchangya.[102]

English is often used for official work alongside Bengali. Other major Indo-Aryan languages such as Hindi, Urdu, Assamese, and Nepali are also familiar to Bengalis.[103]

In addition, several minority ethnolinguistic groups are native to the region. These include speakers of other Indo-Aryan languages (e.g., Bishnupriya Manipuri, Oraon Sadri, various Bihari languages), Tibeto-Burman languages (e.g., A'Tong, Chak, Koch, Garo, Megam, Meitei Manipuri, Mizo, Mru, Pangkhua, Rakhine/Marma, Kok Borok, Riang, Tippera, Usoi, various Chin languages), Austroasiatic languages (e.g., Khasi, Koda, Mundari, Pnar, Santali, War), and Dravidian languages (e.g., Kurukh, Sauria Paharia).[102]

Life expectancy is around 72.49 years for Bangladesh[104] and 70.2 for West Bengal.[105][106] In terms of literacy, West Bengal leads with 77% literacy rate,[100] in Bangladesh the rate is approximately 72.9%.[107][note 3] The level of poverty in West Bengal is at 19.98%, while in Bangladesh it stands at 12.9%[108][109][110]

West Bengal has one of the lowest total fertility rates in India. West Bengal's TFR of 1.6 roughly equals that of Canada.[111]

About 20,000 people live on chars. Chars are temporary islands formed by the deposition of sediments eroded off the banks of the Ganges in West Bengal, which often disappear in the monsoon season. They are made of very fertile soil. The inhabitants of the chars are not recognised by the Government of West Bengal on the grounds that it is not known whether they are Indians or Bangladeshis. Consequently, no identification documents are issued to char-dwellers who cannot benefit from health care, barely survive because of very poor sanitation and are prevented from emigrating to the mainland to find jobs when they have turned 14. On a particular char, it was reported that 13% of women died at childbirth.[112]

Economy

.jpg)

.jpg)

Historically, Bengal has been the industrial leader of the subcontinent.

The region is one of the largest rice producing areas in the world, with West Bengal being India's largest rice producer and Bangladesh being the world's fourth largest rice producer.[113][113] Other key crops include jute, tea, sugarcane and wheat. There are significant reserves of limestone, natural gas and coal. Major industries include textiles, leather goods, pharmaceuticals, shipbuilding, banking and information and communication technology.

Three stock exchanges are located in the region, including the Dhaka Stock Exchange, the Chittagong Stock Exchange and the Calcutta Stock Exchange.

Below is a comparison of economies in the region of Bengal

| Bangladesh | West Bengal (India) |

| US$314.656 billion[114] | US$150 billion[115] |

| US$1,925 per person[116] | US$1,400 per person[117] |

Intra-Bengal trade

Bangladesh and India are the largest trading partners in South Asia, with two-way trade valued at an estimated US$6.9 billion.[118] Much of this trade relationship is centered on some of the world's busiest land ports on the Bangladesh-India border, particularly the West Bengal section.

The partition of India severed the once strong economic links which integrated the region. Decades later, frequent air, rail and bus services are increasingly connecting cities in Bangladesh and West Bengal, as well as the wider region, including Northeast India, Nepal and Bhutan. However the overall economic relationship remains well below potential.

Major cities

Metropolises

The following are the largest cities in Bengal (in terms of population):

| Rank | City | Country | Population (2011) | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dhaka | 8,906,039[119] | ||

| 2 | Kolkata | 4,496,694[120] | ||

| 3 | Chittagong | 2,592,439[121] | ||

| 4 | Khulna | 664,728[122] | ||

| 5 | Durgapur | 566,517[123] |  Durgapur Express Way | |

| 6 | Asansol | 563,917[124] | Modernised ISP, Asansol | |

| 7 | Bogra | 540,000[122] | ||

| 8 | Sylhet | 526,412[122] | ||

| 9 | Siliguri | 513,264[125][126] | ||

| 10 | Rajshahi | 449,756[122] | ||

| 11 | Agartala | 400,004[127] |

Major ports

| Port Name | Type | Status | Location | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port of Chittagong | Sea Port | Active | Chittagong, Chittagong | |

| Port of Haldia | Sea Port River Port |

Active | Haldia, East Midnapur | |

| Port of Mongla | Sea Port | Active | Mongla, Bagerhat, Khulna | |

| Port of Payra | Sea Port | Active | Kalapara, Patuakhali, Barisal | |

| Port of Kolkata | River Port | Active | Kolkata, Kolkata | |

| Port of Narayanganj | River Port | Active | Narayanganj, Dhaka | |

| Port of Benapole-Petrapole | Landport | Active | Sharsha, Jessore-Bangaon, North 24 Parganas |

Tourist attractions

| Name | Type | City/Area | Sample Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sundarbans | World's largest natural mangrove forest |  A Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) from Sundarbans | |

| Cox's Bazar | World's longest uninterrupted sea beach |  Cox's Bazar sea beach | |

| Kuakata | Sea beach | Kuakata sea beach | |

| Digha | Sea beach |  Digha sea beach | |

| Chittagong Hill Tracts | Hilly areas inhabited by different indigenous tribes |  A view of Sajek, Rangamati | |

| Ratargul | Only swamp forest in the Bengal region |  A view of Ratargul | |

| Lawachara National Park | Major national park and nature reserve |  A view of Lawachara national park | |

| Satchhari | Reserve forest |  A view of Satchari national park | |

| Siliguri | Hilly area of foothills of Himalayas |  A view of Siliguri Metropolis |

Strategic importance

.jpg)

The Bengal region is located at the crossroads of two huge economic blocs, the SAARC and ASEAN. It gives access to the sea for the landlocked countries of Bhutan and Nepal, as well as the Seven Sister States of North East India. It is also located near China's southern landlocked region, including Yunnan and Tibet.

Both India and Bangladesh plan to expand onshore and offshore oil and gas operations. Bangladesh is Asia's seventh-largest natural gas producer. Its maritime exclusive economic zone potentially holds many of the largest gas reserves in the Asia-Pacific.[128]

The Bay of Bengal is strategically important for its vital shipping lanes and its central location between the Middle East and the Pacific. The Bay of Bengal Initiative, based in Dhaka, brings together Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Thailand, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka to promote economic integration in the subregion. Other regional groupings include the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Forum for Regional Cooperation (BCIM) and the Bangladesh Bhutan India Nepal (BBIN) Initiative.

Culturally, Bengal is significant for its huge Hindu and Muslim populations. Bengali Hindus make up the second largest linguistic community in India. Bengali Muslims are the world's second largest Muslim ethnicity (after Arab Muslims), and Bangladesh is the world's third largest Muslim-majority country (after Indonesia and Pakistan).

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History |

|

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

|

Festivals

|

|

Genres

Institutions

Awards

|

|

Music and performing arts Folk genres Devotional Classical genres

Modern genres

People Instruments Dance Theater

Organizations People |

|

Sport

|

|

|

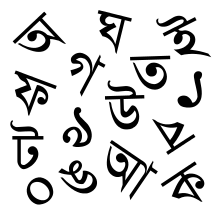

Language

The Bengali language developed between the 7th and 10th centuries from Apabhraṃśa and Magadhi Prakrit.[129] It is written using the indigenous Bengali alphabet, a descendant of the ancient Brahmi script. Bengali is the 5th most spoken language in the world. It is an eastern Indo-Aryan language and one of the easternmost branches of the Indo-European language family. It is part of the Bengali-Assamese languages. Bengali has greatly influenced other languages in the region, including Odia, Assamese, Chakma, Nepali and Rohingya. It is the sole state language of Bangladesh and the second most spoken language in India.[130] It is also the seventh most spoken language by total number of speakers in the world.

Bengali binds together a culturally diverse region and is an important contributor to regional identity. The 1952 Bengali Language Movement in East Pakistan is commemorated by UNESCO as International Mother Language Day, as part of global efforts to preserve linguistic identity.

Currency

In both Bangladesh and West Bengal, currency is commonly denominated as taka. The Bangladesh taka is an official standard bearer of this tradition, while the Indian rupee is also written as taka in Bengali script on all of its banknotes. The history of the taka dates back centuries. Bengal was home one of the world's earliest coin currencies in the first millennium BCE. Under the Delhi Sultanate, the taka was introduced by Muhammad bin Tughluq in 1329. Bengal became the stronghold of the taka. The silver currency was the most important symbol of sovereignty of the Sultanate of Bengal. It was traded on the Silk Road and replicated in Nepal and China's Tibetan protectorate. The Pakistani rupee was scripted in Bengali as taka on its banknotes until Bangladesh's creation in 1971.

Literature

| Bengali literature বাংলা সাহিত্য | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bengali literature | |

| By category Bengali language | |

| Bengali language authors | |

| Chronological list – Alphabetic List | |

| Bengali writers | |

| Writers – Novelists – Poets | |

| Forms | |

| Novel – Poetry – Science Fiction | |

| Institutions and awards | |

| Literary Institutions Literary Prizes | |

| Related Portals Literature Portal India Portal | |

Bengali literature has a rich heritage. It has a history stretching back to the 3rd century BCE, when the main language was Sanskrit written in the brahmi script. The Bengali language and script evolved circa 1000 CE from Magadhi Prakrit. Bengal has a long tradition in folk literature, evidenced by the Chôrjapôdô, Mangalkavya, Shreekrishna Kirtana, Maimansingha Gitika or Thakurmar Jhuli. Bengali literature in the medieval age was often either religious (e.g. Chandidas), or adaptations from other languages (e.g. Alaol). During the Bengal Renaissance of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Bengali literature was modernised through the works of authors such as Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Rabindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Satyendranath Dutta and Jibanananda Das. In the 20th century, prominent modern Bengali writers included Syed Mujtaba Ali, Jasimuddin, Manik Bandopadhyay, Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Buddhadeb Bose, Sunil Gangopadhyay and Humayun Ahmed.

Prominent contemporary Bengali writers in English include Amitav Ghosh, Tahmima Anam, Jhumpa Lahiri and Zia Haider Rahman among others.

Personification

The Bangamata is a female personification of Bengal which was created during the Bengali Renaissance and later adopted by the Bengali nationalists.[131] Hindu nationalists adopted a modified Bharat Mata as a national personification of India.[132] The Mother Bengal represents not only biological motherness but its attributed characteristics as well – protection, never ending love, consolation, care, the beginning and the end of life. In Amar Sonar Bangla, the national anthem of Bangladesh, Rabindranath Tagore has used the word "Maa" (Mother) numerous times to refer to the motherland i.e. Bengal.

Art

The Pala-Sena School of Art developed in Bengal between the 8th and 12th centuries and is considered a high point of classical Asian art.[133][134] It included sculptures and paintings.[135]

Islamic Bengal was noted for its production of the finest cotton fabrics and saris, notably the Jamdani, which received warrants from the Mughal court.[136] The Bengal School of painting flourished in Kolkata and Shantiniketan in the British Raj during the early 20th century. Its practitioners were among the harbingers of modern painting in India.[137] Zainul Abedin was the pioneer of modern Bangladeshi art. The country has a thriving and internationally acclaimed contemporary art scene.[138]

Architecture

Classical Bengali architecture features terracotta buildings. Ancient Bengali kingdoms laid the foundations of the region's architectural heritage through the construction of monasteries and temples (for example, the Somapura Mahavihara). During the sultanate period, a distinct and glorious Islamic style of architecture developed the region.[139] Most Islamic buildings were small and highly artistic terracotta mosques with multiple domes and no minarets. Bengal was also home to the largest mosque in South Asia at Adina. Bengali vernacular architecture is credited for inspiring the popularity of the bungalow.[140]

The Bengal region also has a rich heritage of Indo-Saracenic architecture, including numerous zamindar palaces and mansions. The most prominent example of this style is the Victoria Memorial, Kolkata.

In the 1950s, Muzharul Islam pioneered the modernist terracotta style of architecture in South Asia. This was followed by the design of the Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban by the renowned American architect Louis Kahn in the 1960s, which was based on the aesthetic heritage of Bengali architecture and geography.[141][142]

Sciences

The Gupta dynasty, which is believed to have originated in North Bengal, pioneered the invention of chess, the concept of zero, the theory of Earth orbiting the Sun, the study of solar and lunar eclipses and the flourishing of Sanskrit literature and drama.[68][143] Bengal was the leader of scientific endeavours in the subcontinent during the British Raj. The educational reforms during this period gave birth to many distinguished scientists in the region. Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made very significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[144] IEEE named him one of the fathers of radio science.[145] He was the first person from the Indian subcontinent to receive a US patent, in 1904. In 1924–25, while researching at the University of Dhaka, Prof Satyendra Nath Bose well known for his works in quantum mechanics, provided the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate.[146][147][148] Meghnad Saha was the first scientist to relate a star's spectrum to its temperature, developing thermal ionization equations (notably the Saha ionization equation) that have been foundational in the fields of astrophysics and astrochemistry.[149] Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri was a physicist, known for his research in general relativity and cosmology. His most significant contribution is the eponymous Raychaudhuri equation, which demonstrates that singularities arise inevitably in general relativity and is a key ingredient in the proofs of the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems.[150] In the United States, the Bangladeshi-American engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan emerged as the "father of tubular designs" in skyscraper construction. Ashoke Sen is an Indian theoretical physicist whose main area of work is string theory. He was among the first recipients of the Fundamental Physics Prize “for opening the path to the realisation that all string theories are different limits of the same underlying theory”.[151]

Music

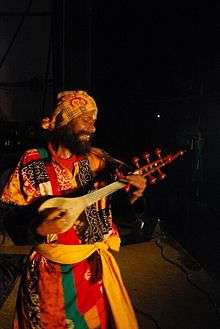

The Baul tradition is a unique heritage of Bengali folk music.[152] The 19th century mystic poet Lalon Shah is the most celebrated practitioner of the tradition.[153] Other folk music forms include Gombhira, Bhatiali and Bhawaiya. Hason Raja is a renowned folk poet of the Sylhet region. Folk music in Bengal is often accompanied by the ektara, a one-stringed instrument. Other instruments include the dotara, dhol, flute, and tabla. The region also has a rich heritage in North Indian classical music.

Cuisine

Bengali cuisine is the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from the Indian subcontinent. Rice and fish are traditional favourite foods, leading to a saying that "fish and rice make a Bengali".[154] Bengal's vast repertoire of fish-based dishes includes Hilsa preparations, a favourite among Bengalis. Bengalis make distinctive sweetmeats from milk products, including Rôshogolla, Chômchôm, and several kinds of Pithe. The old city of Dhaka is noted for its distinct Indo-Islamic cuisine, including biryani, bakarkhani and kebab dishes.

Boats

There are 150 types of Bengali country boats plying the 700 rivers of the Bengal delta, the vast floodplain and many oxbow lakes. They vary in design and size. The boats include the dinghy and sampan among others. Country boats are a central element of Bengali culture and have inspired generations of artists and poets, including the ivory artisans of the Mughal era. The country has a long shipbuilding tradition, dating back many centuries. Wooden boats are made of timber such as Jarul (dipterocarpus turbinatus), sal (shorea robusta), sundari (heritiera fomes), and Burma teak (tectons grandis). Medieval Bengal was shipbuilding hub for the Mughal and Ottoman navies.[155][156] The British Royal Navy later utilised Bengali shipyards in the 19th century, including for the Battle of Trafalgar.

Attire

Bengali women commonly wear the shaŗi and the salwar kameez, often distinctly designed according to local cultural customs. In urban areas, many women and men wear Western-style attire. Among men, European dressing has greater acceptance. Men also wear traditional costumes such as the kurta with dhoti or pyjama, often on religious occasions. The lungi, a kind of long skirt, is widely worn by Bangladeshi men.

Festivals

Durga Puja is the biggest festival of the Hindus in Bengal as well as the most significant socio-cultural event of the region in general.[157] The two Eids and Muharram are the important festivals for Muslims. Christmas (called Borodin in Bengali) is also a major festival where people irrespective of their beliefs and faiths participate. Other major festivals include Kali Puja, Saraswati Puja, Holi, Rath Jatra, Janmashtami, Poila Boishakh and Poush Parbon.

Media

Bangladesh has a diverse, outspoken and privately owned press, with the largest circulated Bengali language newspapers in the world. English-language titles are popular in the urban readership.[158] West Bengal had 559 published newspapers in 2005,[159] of which 430 were in Bengali.[159] Bengali cinema is divided between the media hubs of Kolkata and Dhaka.

Sports

Cricket and football are popular sports in the Bengal region. Local games include sports such as Kho Kho and Kabaddi, the latter being the national sport of Bangladesh. An Indo-Bangladesh Bengali Games has been organised among the athletes of the Bengali speaking areas of the two countries.[160]

See also

- Bengali Renaissance

- Bengalis

- Greater Bengal

- East India

- Hindi Belt

- List of Bengalis

- North-East India

- Punjab

Notes

- especially Direct Action Day in Calcutta and then in Noakhali in 1946

- Roughly 163 million in Bangladesh and 100 million in the Republic of India (CIA Factbook 2014 estimates, numbers subject to rapid population growth); about 3 million Bangladeshis in the Middle East, 1 million Bengalis in Pakistan, 0.4 million British Bangladeshi.

- CRI do not give a breakdown by gender or state the age bracket for the data

References

- "Bengalis". Facts and Details. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- "Article 2. The state language". The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd. Ministry of Law, The People's Republic of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 47th report (July 2008 to June 2010)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 122–126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Oxford Dictionaries". Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Arijit Mazumdar (27 August 2014). Indian Foreign Policy in Transition: Relations with South Asia. Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-317-69859-3.

- "50th REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh – the World's Longest Beach". ThingsAsian. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian by Mccrindle, J.W. archive.org. Mccrindle, J. W. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 277–287. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- R. C. Majumdar (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- Nanda, J. N (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. 2005. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- Ibn Battutah. The Rehla of Ibn Battuta.

- "The paradise of nations | Dhaka Tribune". Archive.dhakatribune.com. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237–240, World History in Context. Retrieved 3 August 2017

- John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- Giorgio Riello, Tirthankar Roy (2009). How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500–1850. Brill Publishers. p. 174. ISBN 9789047429975.

- Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, page 202, University of California Press

- Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- M. Shahid Alam (2016). Poverty From The Wealth of Nations: Integration and Polarization in the Global Economy since 1760. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-333-98564-9.

- Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed).

- Maddison, Angus (2003): Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics, OECD Publishing, ISBN 9264104143, pages 259–261

- Lawrence E. Harrison, Peter L. Berger (2006). Developing cultures: case studies. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 9780415952798.

- Lex Heerma van Voss; Els Hiemstra-Kuperus; Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk (2010). "The Long Globalization and Textile Producers in India". The Ashgate Companion to the History of Textile Workers, 1650–2000. Ashgate Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 9780754664284.

- P. J. Marshall (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780521028226.

- C. C. Davies (1957). "Chapter XXIII: Rivalries in India". In J. O. Lindsay (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History. Volume VII: The Old Regime 1713–63. Cambridge University Press. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-521-04545-2.

- Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Rahman, Urmi (2014). Bangladesh – Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture. Kuperard. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-85733-696-2.

- "Vanga | Britannica.com". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Ghulam Husain Salim, The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1902.

- Land of Two Rivers, Nitish Sengupta

- Abu'l-Fazl. Ain-i-Akbari.

- "Bangladesh: early history, 1000 B.C.–A.D. 1202". Bangladesh: A country study. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. September 1988. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

Historians believe that Bengal, the area comprising present-day Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, was settled in about 1000 B.C. by Dravidian-speaking peoples who were later known as the Bang. Their homeland bore various titles that reflected earlier tribal names, such as Vanga, Banga, Bangala, Bangal, and Bengal.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

In C1020 ... launched Rajendra's great northern escapade ... peoples he defeated have been tentatively identified ... 'Vangala-desa where the rain water never stopped' sounds like a fair description of Bengal in the monsoon.

- Allan, John Andrew; Haig, T. Wolseley; Dodwell, H. H. (1934). Dodwell, H. H. (ed.). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 113.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 281. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Lach, Donald F.; Kley, Edwin J. Van (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 3: Southeast Asia. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1124–. ISBN 978-0-226-46768-9.

- Ali, A (1996). "Vulnerability of Bangladesh to climate change and sea level rise through tropical cyclones and storm surges". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 92 (1–2): 171–179. doi:10.1007/BF00175563 (inactive 8 August 2020).

- Summit Elevations: Frequent Internet Errors. Archived 25 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 April 2006.

- IUCN (1997). "Sundarban wildlife sanctuaries Bangladesh". World Heritage Nomination-IUCN Technical Evaluation.

- "Statistical Facts about India". indianmirror.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- "National Himalayan Sandakphu-Gurdum Trekking Expedition: 2006". Youth Hostels Association of India: West Bengal State Branch. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- Chowdhury, U. K.; Biswas, B. K.; Chowdhury, T. R.; et al. (May 2000). "Groundwater arsenic contamination in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India". Environmental Health Perspectives. 108 (4): 393–397. doi:10.2307/3454378. JSTOR 3454378. PMC 1638054. PMID 10811564. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Lethbridge, E. (1874). An Easy Introduction to the History and Geography of Bengal: For the Junior Classes in Schools. Thacker. p. 5. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Akhter, Nasrin (2012). "Sarkar". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- David Christiana (1 September 2007). "Arsenic Mitigation in West Bengal, India: New Hope for Millions" (PDF). Southwest Hydrology. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- Puri, Sunil (2007). Agroforestry: Systems and Practices. ISBN 9788189422622.

- Reddy, Angadi Ranga (2009). Gandhi and globalisation. ISBN 9788183242967.

- Das, Tulshi Kumar (2000). Social Structure and Cultural Practices in Slums: A Study of Slums in Dhaka City. ISBN 9788172111106.

- Andaya, B. W.; Andaya, L. Y. (2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400–1830. Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-521-88992-6. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Singh, A. K. (2006). Modern World System and Indian Proto-industrialization: Bengal 1650–1800. 1. Northern Book Centre. p. 225. ISBN 9788172112011. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Banu, U. A. B. Razia Akter (1992). Islam in Bangladesh. Brill. p. 6. ISBN 978-90-04-09497-0. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

in Samatata (South-east Bengal) where the Buddhist Khadaga dynasty ruled throughout the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries AD.

- Rashid, M Harunar (2012). "Harikela". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Chittagong to bridge S Asian nations". The Daily Star. 17 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "World's longest natural sea beach under threat". BBC News. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Bangladesh finds 106 tigers in Sundarbans, India 76". Dhaka Tribune. BSS. 4 October 2015. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- "History of Bangladesh". Bangladesh Student Association. Archived from the original on 19 December 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- "4000-year old settlement unearthed in Bangladesh". Xinhua News Agency. March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Eaton, R. M. (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Ray, H. P. (2003). The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-01109-9. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Chowdhury, AM. "Gangaridai". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Sarkar, Sebanti, "https://scroll.in/magazine/868330/in-rural-bengal-an-indefatigable-relic-hunter-has-uncovered-a-hidden-chapter-of-history Archived 20 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine." Retrieved 4 August 2018

- Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, Mahasthan: Anecdote to History, 2006, pp. 69–73, Dibyaprakash, 38/2 ka Bangla Bazar, Dhaka, ISBN 984-483-245-4

- Ghosh, Suchandra. "Pundravardhana". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- Majumdar, R. C., History of Ancient Bengal, First published 1971, Reprint 2005, p. 10, Tulshi Prakashani, Kolkata, ISBN 81-89118-01-3.

- (Mbh 1:104), (2:21).

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913). A History of Chess. Benjamin Press (originally published by Oxford University Press). ISBN 978-0-936317-01-4. OCLC 13472872.

- Islam, Shariful (2012). "Bangla Script". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Sengupta, Nitish K. (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. pp. 39–49. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- Nanda, J. N. (1 January 2005). Bengal: The Unique State. Concept Publishing Company. p. 34. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

- Mehta, Jaswant Lal (1979). Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 82. ISBN 978-81-207-0617-0.

- A Collection of Treaties and Engagements with the Native Princes and States of Asia: Concluded on Behalf of the East India Company by the British Governments in India, Viz. by the Government of Bengal Etc. : Also Copies of Sunnuds Or Grants of Certain Privileges and Imunities to the East India Company by the Mogul and Other Native Princes of Hindustan. United East-India Company. 1812. p. 28. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Ahmed, F. S. (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson. ISBN 9788131732021. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- 5 of the worst atrocities carried out by the British Empire. The Independent. 19 January 2016.

- Churchill's policies contributed to 1943 Bengal famine – study. The Guardian. 29 March 2019.

- The "Gandhians" of Bengal: Nationalism, Social Reconstruction and Cultural Orientations 1920-1942. p. 19.

Malaria was endemic in rural areas during the 19th century, particularly in western Bengal. This was ... The famine of 1769-70 resulted in about ten million deaths, while 50 million died of malaria, plague and famine between 1895 and 19206.

- (Baxter 1997, pp. 39–40)

- Chowdhury, Masud Hasan. "Cyclone". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- Chitta Ranjan Misra. "United Independent Bengal Movement". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Harun-or-Rashid. "Partition of Bengal, 1947". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Suranjan Das. "Calcutta Riot (1946)". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Communist rule ends in Indian state of West Bengal". BBC News. 13 May 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Bhattacharyya, B. (1986). Tripura Administration: The Era of Modernisation, 1870–1972. Mittal Publications. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "Muhammad Ali Bogra becomes Prime Minister". Story of Pakistan. June 2003. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "Revisiting 1906–1971". The Nation. Pakistan. 4 December 2015. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "H. S. Suhrawardy Becomes Prime Minister". Story of Pakistan. July 2003. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- (Baxter 1997, pp. 78–79)

- Raghavan, S. (2013). 1971. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-73129-5. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Lewis, David (2011). Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–90. ISBN 978-0-521-71377-1.

- "Dhaka Declaration" (PDF). SAARC Secretariat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Bangladesh profile – Timeline". BBC News. 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Salik, Siddiq (1978). Witness to Surrender. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577264-7.

- Burke, S (1973). "The Postwar Diplomacy of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971". Asian Survey. 13 (11): 1036–1049. doi:10.2307/2642858. JSTOR 2642858.

- "Address by External Affairs Minister Shri Natwar Singh at India-Bangladesh Dialogue Organised by Centre for Policy Dialogue and India International Centre". Speeches. Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi. 7 August 2005. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Chattopadhyay, S. S. (June 2007). "Constant traffic". Frontline. Vol. 24 no. 11. The Hindu. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "2011 Population & Housing Census: Preliminary Results" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Area, population, decennial growth rate and density for 2001 and 2011 at a glance for West Bengal and the districts: provisional population totals paper 1 of 2011: West Bengal". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "Provisional Population Totals: West Bengal". Census of India, 2001. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 14 May 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2006.

- World Bank Development Indicators Database, 2006.

- "Bangladesh". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Detailed relations between Bengali and related dialects and languages in eastern India in Sudhāṃśu Śekhara Tuṅga, Bengali and Other Related Dialects of South Assam (Delhi: Mittal, 1995). ISBN 9788170995883

- "The World Factbook: Bangladesh". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- "Contents 2010–14" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "Abridged Life Tables- 2010–14" (PDF). Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- CRI=Center Research and Information (2014). Bangladesh Education for All. CRI Publication. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7566-9859-1. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "Table 162, Number and Percentage of Population Below Poverty Line". Reserve Bank of India, Government of India. 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- Misha, Farzana; Sulaiman, Munshi. "Bangladesh Priorities: Poverty, Sulaiman and Misha | Copenhagen Consensus Center". copenhagenconsensus.com. Copenhagen Consensus. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "Statistics". UNICEF. 18 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2007.