Galatia

Galatia (/ɡəˈleɪʃə/; Ancient Greek: Γαλατία, Galatía, "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (cf. Tylis), who settled here and became its ruling caste in the 3rd century BC, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC. It has been called the "Gallia" of the East, Roman writers calling its inhabitants Galli (Gauls or Celts).

| Galatia | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Region of Anatolia | |

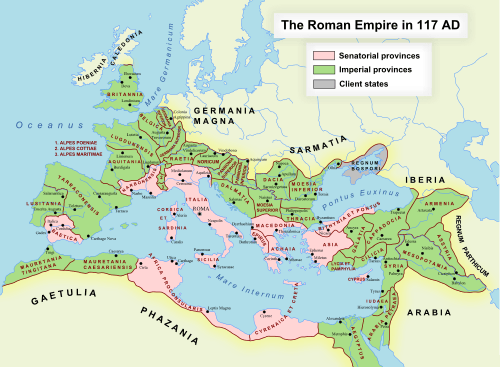

Asia Minor/Anatolia in the Greco-Roman period. The classical regions and their main settlements, including Galatia. | |

| Location | Central Anatolia |

| State existed | 280–64 BC |

| Successive languages | Galatian, Greek |

| Achaemenid satrapy | Cappadocia |

| Roman province | Galatia |

Geography

Galatia was bounded on the north by Bithynia and Paphlagonia, on the east by Pontus and Cappadocia, on the south by Cilicia and Lycaonia, and on the west by Phrygia. Its capital was Ancyra (i.e. Ankara, today the capital of modern Turkey).

Celtic Galatia

The terms "Galatians" came to be used by the Greeks for the three Celtic peoples of Anatolia: the Tectosages, the Trocmii, and the Tolistobogii.[1][2] By the 1st century BC the Celts had become so Hellenized that some Greek writers called them Hellenogalatai (Ἑλληνογαλάται).[3][4] The Romans called them Gallograeci.[4] Though the Celts had, to a large extent, integrated into Hellenistic Asia Minor, they preserved their linguistic and ethnic identity.[1]

By the 4th century BC the Celts had penetrated into the Balkans, coming into contact with the Thracians and Greeks.[5] In 380 BC they fought in the southern regions of Dalmatia (present day Croatia), and rumors circulated around the ancient world that Alexander the Great's father, Philip II of Macedonia had been assassinated by a dagger of Celtic origins.[6][7] Arrian writes that "Celts established on the Ionic coast" were among those who came to meet Alexander the Great during a campaign against the Getae in 335 BC.[8] Several ancient accounts mention that the Celts formed an alliance with Dionysius I of Syracuse who sent them to fight alongside the Macedonians against the Thebans.[9] In 279 BC two Celtic factions united under the leadership of Brennus and began to push southwards from southern Bulgaria towards the Greek states. According to Livy, a sizable force split off from this main group and head toward Asia Minor.[10]

For several years a federation of Hellespontine cities, including Byzantion and Chalkedon prevented the Celts from entering Asia Minor.[4][1] During the course of the power struggle between Nikomedes I of Bithynia and his brother Zipoetes, the former hired 20,000 Galatian mercenaries. The Galatians split into two groups headed by Leonnorius and Lutarius respectively, which crossed the Bosporus and the Hellespont respectively. In 277 BC, when the hostilities had ended the Galatians came out of Nikomedes' control and began raiding Greek cities in Asia Minor while Antiochus was solidifying his rule in Syria. The Galatians looted Cyzikus, Ilion, Didyma, Priene, Thyatira and Laodicea on the Lycus, while the citizens of Erythras paid them ransom. Either in 275 or 269 BC Antiochus' army faced the Galatians somewhere on the plain of Sardis in the Battle of Elephants. In the aftermath of the battle the Celts then settled in northern Phrygia, a region that eventually came to be known as Galatia.[11]

The territory of Celtic Galatia included the cities of Ancyra (present day Ankara), Pessinus, Tavium, and Gordion.[12]

Roman Galatia

Upon the death of Deiotarus, the Kingdom of Galatia was given to Amyntas, an auxiliary commander in the Roman army of Brutus and Cassius who gained the favor of Mark Antony.[13] After his death in 25 BC, Galatia was incorporated by Augustus into the Roman Empire, becoming a Roman province.[14] Near his capital Ancyra (modern Ankara), Pylamenes, the king's heir, rebuilt a temple of the Phrygian god Men to venerate Augustus (the Monumentum Ancyranum), as a sign of fidelity. It was on the walls of this temple in Galatia that the major source for the Res Gestae of Augustus were preserved for modernity. Few of the provinces proved more enthusiastically loyal to Rome.

Josephus related the Biblical figure Gomer to Galatia (or perhaps to Gaul in general): "For Gomer founded those whom the Greeks now call Galatians, [Galls], but were then called Gomerites."[15] Others have related Gomer to Cimmerians.

Paul the Apostle visited Galatia in his missionary journeys,[16] and wrote to the Christians there in the Epistle to the Galatians.

Although originally possessing a strong cultural identity, by the 2nd century AD, the Galatians had become assimilated (Hellenization) into the Hellenistic civilization of Anatolia.[17] The Galatians were still speaking the Galatian language in the time of St. Jerome (347–420 AD), who wrote that the Galatians of Ancyra and the Treveri of Trier (in what is now the Rhineland) spoke the same language (Comentarii in Epistolam ad Galatos, 2.3, composed c. 387).

In an administrative reorganisation (c. 386–395), two new provinces succeeded it, Galatia Prima and Galatia Secunda or Salutaris, which included part of Phrygia. The fate of the Galatian people is a subject of some uncertainty, but they seem ultimately to have been absorbed into the Greek-speaking populations of Anatolia.

Gallery

A Galatian's head as depicted on a gold Thracian objet d'art, 3rd century BC. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

A Galatian's head as depicted on a gold Thracian objet d'art, 3rd century BC. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Galatian bracelets and earrings, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Galatian bracelets and earrings, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Galatian torcs, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Galatian torcs, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Galatian plate, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Galatian plate, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Galatian object, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Galatian object, 3rd century BC, Hidirsihlar tumulus, Bolu. Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Part of a 15th-century map showing Galatia.

Part of a 15th-century map showing Galatia.

Notes

- Strobel, Karl (2013). "Central Anatolia". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-984653-5. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Esler, Philip Francis (1998). Galatians. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-415-11037-2.

Galatai was the Greek word used for the Celts from beyond the Rhine who invaded regions of Macedonia, Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor in the period 280-275 BCE

- See Diod.5.32-3; Just.26.2. Cf. Liv.38.17; Strabo 13.4.2.

- Enenkel, K. A. E.; Pfeijffer, Ilja Leonard (January 2005). The Manipulative Mode: Political Propaganda in Antiquity : a Collection of Case Studies. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14291-6.

- See The Periplus of Scylax (18-19)

- See Diod. 16, 94, 3

- Moscati, Sabatino; Grassi, Palazzo (1999). "4: Ancient Literary Sources". The Celts. Random House Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8478-2193-8.

- See also Strabo, vii, 3, 8.

- Justin, xx, 4, 9; Xen., Hell., vii, 1, 20, 31; Diod., xv, 70. For a full discussion see Henri Hubert, The Rise of the Celts, 1966 pp. 5-6

- Cunliffe, Barry (2018-04-10). The Ancient Celts. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-875293-6.

- Sartre 2006, pp. 128–129,77.

- Krentz, Edgar (1985-01-01). Galatians. Augsburg Publishing House. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8066-2166-1.

- It appears Amyntas was quite prodigious in striking coins for his various exploits (with his title as King) —Asia Minor Coins – Amyntas

-

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews, I:6.

- Acts 16:6 and Acts 18:23

- Galatia

References

- Encyclopedia, MS Encarta 2001, under article "Galatia".

- Barraclough, Geoffrey, ed. HarperCollins Atlas of World History. 2nd ed. Oxford: HarperCollins, 1989. 76–77.

- John King, Celt Kingdoms, pg. 74–75.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia, VI: Epistle to the Galatians.

- Stephen Mitchell, 1993. Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor vol. 1: "The Celts and the Impact of Roman Rule." (Oxford: Clarendon Press) 1993. ISBN 0-19-814080-0. Concentrates on Galatia; volume 2 covers "The Rise of the Church". (Bryn Mawr Classical Review)

- David Rankin, (1987) 1996. Celts and the Classical World (London: Routledge): Chapter 9 "The Galatians".

- Coşkun, A., "Das Ende der "romfreundlichen Herrschaft" in Galatien und das Beispiel einer "sanften Provinzialisierung" in Zentralanatolien," in Coşkun, A. (hg), Freundschaft und Gefolgschaft in den auswärtigen Beziehungen der Römer (2. Jahrhundert v. Chr. – 1. Jahrhundert n. Chr.), (Frankfurt M. u. a., 2008) (Inklusion, Exklusion, 9), 133–164.

- Justin K. Hardin: Galatians and the Imperial Cult. A Critical Analysis of the First-Century Social Context of Paul's Letter. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany 2008, ISBN 978-3-16-149563-2.

- Sartre, Maurice (2006). Ελληνιστική Μικρασία: Aπο το Αιγαίο ως τον Καύκασο [Hellenistic Asia Minor: From the Aegean to the Caucaus] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdoseis Pataki. ISBN 9789601617565.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Galatia. |