Hyperborea

In Greek mythology the Hyperboreans (Ancient Greek: Ὑπερβόρε(ι)οι, pronounced [hyperbóre(ː)ɔi̯]; Latin: Hyperborei) were a race of giants who lived "beyond the North Wind". The Greeks thought that Boreas, the god of the North Wind (one of the Anemoi, or "Winds") lived in Thrace, and therefore Hyperborea indicates that it is a region beyond Thrace.

This land was supposed to be perfect, with the sun shining twenty-four hours a day, which to modern ears suggests a possible location within the Arctic Circle during the midnight sun-time of year. It is also possible that Hyperborea had no real physical location at all, for according to the classical Greek poet Pindar, "neither by ship nor on foot would you find the marvellous road to the assembly of the Hyperboreans."

Pindar also described the otherworldly perfection of the Hyperboreans:

Never the Muse is absent

from their ways: lyres clash and flutes cry

and everywhere maiden choruses whirling.

Neither disease nor bitter old age is mixed

in their sacred blood; far from labor and battle they live.[1]

Early sources

Herodotus

The earliest extant source that mentions Hyperborea in detail, Herodotus's Histories (Book IV, Chapters 32–36),[2] dates from circa 450 BC.[3] However, Herodotus recorded three earlier sources that supposedly mentioned the Hyperboreans, including Hesiod and Homer, the latter purportedly having written of Hyperborea in his lost work Epigoni: "if that be really a work of his". Herodotus also wrote that the 7th-century BC poet Aristeas wrote of the Hyperboreans in a poem (now lost) called Arimaspea about a journey to the Issedones, who are estimated to have lived in the Kazakh Steppe.[4] Beyond these lived the one-eyed Arimaspians, further on the gold-guarding griffins, and beyond these the Hyperboreans.[5] Herodotus assumed that Hyperborea lay somewhere in Northeast Asia.

Pindar, Simonides of Ceos and Hellanicus of Lesbos, contemporaries of Herodotus in the 5th century BC, each briefly described or referenced the Hyperboreans in their works.[6]

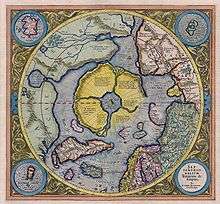

Location of Hyperborea

The Hyperboreans were believed to live beyond the snowy Riphean Mountains.

According to Pausanias: "The land of the Hyperboreans, men living beyond the home of Boreas."[7]

Homer placed Boreas in Thrace, and therefore Hyperborea was in his opinion north of Thrace, in Dacia.[8]

Sophocles (Antigone, 980–987), Aeschylus (Agamemnon, 193; 651), Simonides of Ceos (Schol. on Apollonius Rhodius, 1. 121) and Callimachus (Delian, [IV] 65) also placed Boreas in Thrace.[9] Other ancient writers, however, believed the home of Boreas or the Riphean Mountains were in a different location. For example, Hecataeus of Miletus believed that the Riphean Mountains were adjacent to the Black Sea.[8] Alternatively Pindar placed the home of Boreas, the Riphean Mountains and Hyperborea all near the Danube.[10] Heraclides Ponticus and Antimachus in contrast identified the Riphean Mountains with the Alps, and the Hyperboreans as a Celtic tribe (perhaps the Helvetii) who lived just beyond them.[11] Aristotle placed the Riphean mountains on the borders of Scythia, and Hyperborea further north.[12] Hecataeus of Abdera and others believed Hyperborea was Britain (see below).

Later Roman and Greek sources continued to change the location of the Riphean mountains, the home of Boreas, as well as Hyperborea, supposedly located beyond them. However, all these sources agreed these were all in the far north of Greece or southern Europe.[13] The ancient grammarian Simmias of Rhodes in the 3rd century BC connected the Hyperboreans to the Massagetae[14] and Posidonius in the 1st century BC to the Western Celts, but Pomponius Mela placed them even further north in the vicinity of the Arctic.[15]

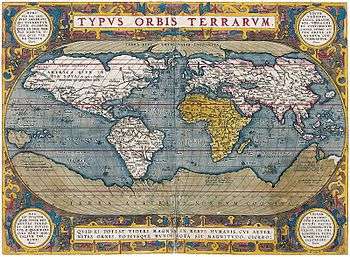

In maps based on reference points and descriptions given by Strabo,[16] Hyperborea, shown variously as a peninsula or island, is located beyond what is now France, and stretches further north-south than east-west.[17] Other descriptions put it in the general area of the Ural Mountains.

Later classical sources

Plutarch, writing in the 1st century AD, connected the Hyperboreans with the Gauls who had sacked Rome in the 4th century BC (see Battle of the Allia).[18]

Aelian, Diodorus Siculus and Stephen of Byzantium all recorded important ancient Greek sources on Hyperborea, but added no new descriptions.[19]

The 2nd century AD Stoic philosopher Hierocles equated the Hyperboreans with the Scythians, and the Riphean Mountains with the Ural Mountains.[20] Clement of Alexandria and other early Christian writers also made this same Scythian equation.[21]

Ancient identification with Britain

Hyperborea was identified with Britain first by Hecataeus of Abdera in the 4th century BC, as in a preserved fragment by Diodorus Siculus:

In the regions beyond the land of the Celts there lies in the ocean an island no smaller than Sicily. This island, the account continues, is situated in the north and is inhabited by the Hyperboreans, who are called by that name because their home is beyond the point whence the north wind (Boreas) blows; and the island is both fertile and productive of every crop, and has an unusually temperate climate.[22]

Hecateaus of Abdera also wrote that the Hyperboreans had on their island "a magnificent sacred precinct of Apollo and a notable temple which is adorned with many votive offerings and is spherical in shape". Some scholars have identified this temple with Stonehenge.[19][23] Diodorus, however, does not identify Hyperborea with Britain, and his description of Britain (5.21–23) makes no mention of the Hyperboreans or their spherical temple. (See the section "Legends" below.)

Pseudo-Scymnus, around 90 BC, wrote that Boreas dwelled at the extremity of Gaulish territory, and that he had a pillar erected in his name on the edge of the sea (Periegesis, 183). Some have claimed this is a geographical reference to northern France, and Hyperborea as the British Isles which lay just beyond the English Channel.[24]

Ptolemy (Geographia, 2. 21) and Marcian of Heraclea (Periplus, 2. 42) both placed Hyperborea in the North Sea which they called the "Hyperborean Ocean".[25]

In his 1726 work on the druids, John Toland specifically identified Diodorus' Hyperborea with the Isle of Lewis, and the spherical temple with the Callanish Stones.[26]

Legends

Along with Thule, Hyperborea was one of several terrae incognitae to the Greeks and Romans, where Pliny, Pindar and Herodotus, as well as Virgil and Cicero, reported that people lived to the age of one thousand and enjoyed lives of complete happiness. Hecataeus of Abdera collated all the stories about the Hyperboreans current in the fourth century BC and published a lengthy treatise on them, lost to us, but noted by Diodorus Siculus (ii.47.1–2).[27] Also, the sun was supposed to rise and set only once a year in Hyperborea, which would place it above or upon the Arctic Circle, or, more generally, in the arctic polar regions.

The ancient Greek writer Theopompus in his work Philippica claimed Hyperborea was once planned to be conquered by a large race of soldiers from another island (some have claimed this was Atlantis), the plan though was abandoned because the soldiers from Meropis realized the Hyperboreans were too strong for them and the most blessed of people; this unusual tale, which some believe was satire or comedy, was preserved by Aelian (Varia Historia, 3. 18).

Theseus visited the Hyperboreans and Pindar transferred Perseus's encounter with Medusa there from its traditional site in Libya, to the dissatisfaction of his Alexandrian editors.[28]

Apollonius wrote that the Argonauts sighted Hyperborea, when they sailed through Eridanos.

Hyperboreans in Delos

Alone among the Twelve Olympians, Apollo was venerated among the Hyperboreans, the Hellenes thought: he spent his winter amongst them.[29] According to Herodotus, offerings from the Hyperboreans came to Scythia packed with straw, and they were passed from tribe to tribe until they arrived at Dodona and from them to other Greek peoples until they to came to Apollo's temple on Delos. He says they used this method because the first time the gifts were brought by two maidens, Hyperoche and Laodice, with an escort of five men, but none of them returned. To prevent that, since then the Hyperboreans brought the gifts to their borders and asked their neighbours to deliver them to the next country and so on until they arrived to Delos.[30]

Herodotus also details that other two virgin maidens, Arge and Opis, had come from Hyperborea to Delos before, as a tribute to the goddess Ilithyia for ease of child-bearing, accompanied by the gods themselves. The maidens received honours in Delos, where the women collected gifts from them and sang hymns to them.[30]

Abaris the Hyperborean

A particular Hyperborean legendary healer was known as "Abaris" or "Abaris the Healer" whom Herodotus first described in his works. Plato (Charmides, 158C) regarded Abaris as a physician from the far north, while Strabo reported Abaris was Scythian like the early philosopher Anacharsis (Geographica, 7. 3. 8).

Physical appearance

Greek legend asserts that the Boreades, who were the descendants of Boreas and the snow-nymph Chione (or Khione), founded the first theocratic monarchy on Hyperborea. This legend is found preserved in the writings of Aelian:

This god [Apollon] has as priests the sons of Boreas [North Wind] and Chione [Snow], three in number, brothers by birth, and six cubits in height [about 3 metres].[31]

Diodorus Siculus added to this account:

And the kings of this (Hyperborean) city and the supervisors of the sacred precinct are called Boreadae, since they are descendants of Boreas, and the succession to these positions is always kept in their family.[32]

The Boreades were thus believed to be giant kings, around 10 feet (3.0 m) tall, who ruled Hyperborea.

No other physical descriptions of the Hyperboreans are provided in classical sources.[33] However, Aelius Herodianus, a grammarian in the 3rd century, wrote that the mythical Arimaspi were identical to the Hyperboreans in physical appearance (De Prosodia Catholica, 1. 114) and Stephanus of Byzantium in the 6th century wrote the same (Ethnica, 118. 16). The ancient poet Callimachus described the Arimaspi as having fair hair[34] but it is disputed whether the Arimaspi were Hyperboreans.[35]

From east to west: Celts as Hyperboreans

Six classical Greek authors also came to identify these mythical people at the back of the North Wind with their Celtic neighbours in the north: Antimachus of Colophon, Protarchus, Heraclides Ponticus, Hecataeus of Abdera, Apollonius of Rhodes and Posidonius of Apamea. The way the Greeks understood their relationship with non-Greek peoples was significantly moulded by the way myths of the Golden Age were transplanted into the contemporary scene, especially in the context of Greek colonisation and trade. As the Riphean mountains of the mythical past were identified with the Alps of northern Italy, there was at least a geographic rationale for identifying the Hyperboreans with the Celts living in and beyond the Alps, or at least the Hyperborean lands with the lands inhabited by the Celts. A reputation for feasting and a love of gold may have reinforced the connection.[36]

In Ireland, however, the Celts had their own legends of an advanced civilization in the far north. The Book of Invasions records that this civilization was established by migrants from Ireland, whose descendants returned to settle Ireland several centuries later:

Bethach son of Iarbonel the Soothsayer son of Nemed: his descendants went into the northern islands of the world to learn druidry and heathenism and diabolical knowledge, so that they became expert in all the arts. And their descendants were the Tuatha De Danann ... These latter acquired knowledge and science and diabolism in four cities: Failias, Goirias, Findlias and Muirias ... Thereafter the Tuatha De Danann came to Ireland, without ships, passing through the air in dark clouds.[37]

Modern interpretations

As with other legends of this sort, details can be selectively reconciled with modern knowledge. Above the Arctic Circle, from the spring equinox to the autumnal equinox (depending on latitude), the sun can shine for 24 hours a day; at the extreme (that is, the Pole), it rises and sets only once a year, possibly leading to the erroneous conclusion that a "day" for such persons is a year long, and therefore that living a thousand days would be the same as living a thousand years.

Since Herodotus places the Hyperboreans beyond the Massagetae and Issedones, both Central Asian peoples, it appears that his Hyperboreans may have lived in Siberia. Heracles sought the golden-antlered hind of Artemis in Hyperborea. As the reindeer is the only deer species of which females bear antlers, this would suggest an arctic or subarctic region. Following J. D. P. Bolton's location of the Issedones on the south-western slopes of the Altay mountains, Carl P. Ruck places Hyperborea beyond the Dzungarian Gate into northern Xinjiang, noting that the Hyperboreans were probably Chinese.[38]

Amber arrived in Greek hands from some place known to be far to the north. Avram Davidson proposed the theory that Hyperborea was derived from a logical (though erroneous) explanation by the Greeks for the insects, which apparently originated in a warm climate, found embedded inside the amber arriving in their cities from cold northern countries.[39]

Unaware of the explanation offered by modern science (i.e. that these insects had lived in times when the climate of northern Europe was much warmer, their bodies preserved unchanged in the amber) the Greeks came up with the idea that the coldness of northern countries was due to the cold breath of Boreas, the North Wind. So if one travelled "beyond Boreas" one would find a warm and sunny land.

Identification as Hyperboreans

Northern Europeans (Scandinavians), when confronted with the classical Greco-Roman culture of the Mediterranean, identified themselves with the Hyperboreans. This aligns with the traditional aspect of a perpetually sunny land beyond the north, since the Northern half of Scandinavia faces long days during high summer with no hour of darkness (‘mid-night sun’). This idea was especially strong during the 17th century in Sweden, where the later representatives of the ideology of Gothicism declared the Scandinavian peninsula both the lost Atlantis and the Hyperborean land. European culture equally self-identified as Hyperborean; thus Washington Irving, in elaborating on Astoria in the Pacific Northwest, was of the opinion that

While the fiery and magnificent Spaniard, inflamed with the mania for gold, has extended his discoveries and conquests over those brilliant countries scorched by the ardent sun of the tropics, the adroit and buoyant Frenchman, and the cool and calculating Briton, have pursued the less splendid, but no less lucrative, traffic in furs amidst the hyperborean regions of the Canadas, until they have advanced even within the Arctic Circle.[40]

In this vein the self-described "Hyperborean-Roman Company" (Hyperboreisch-römische Gesellschaft) were a group of northern European scholars who studied classical ruins in Rome, founded in 1824 by Theodor Panofka, Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, August Kestner and Eduard Gerhard. Friedrich Nietzsche referred to his sympathetic readers as Hyperboreans in The Antichrist (written 1888, published 1895): "Let us look each other in the face. We are Hyperboreans – we know well enough how remote our place is." He quoted Pindar and added "Beyond the North, beyond the ice, beyond death – our life, our happiness."

The term "Hyperborean" still sees some jocular contemporary use in reference to groups of people who live in a cold climate. Under the Library of Congress Classification System, the letter subclass PM includes "Hyperborean Languages", a catch-all category that refers to all the linguistically unrelated languages of peoples living in Arctic regions, such as the Inuit.

Hyperborean Indo-European hypothesis

John G. Bennett wrote a research paper entitled "The Hyperborean Origin of the Indo-European Culture" (Journal Systematics, Vol. 1, No. 3, December 1963) in which he claimed the Indo-European homeland was in the far north, which he considered the Hyperborea of classical antiquity.[41] This idea was earlier proposed by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (whom Bennett credits) in his The Arctic Home in the Vedas (1903) as well as the Austro-Hungarian ethnologist Karl Penka (Origins of the Aryans, 1883).[42]

Hyperborea in modern esoteric thought

H. P. Blavatsky, René Guénon and Julius Evola all shared the belief in the Hyperborean, polar origins of Mankind and a subsequent solidification and devolution.[43] According to these esotericists, Hyperborea was the Golden Age polar center of civilization and spirituality; mankind does not rise from the ape, but progressively devolves into the apelike condition as it strays physically and spiritually from its mystical otherworldly homeland in the Far North, succumbing to the demonic energies of the South Pole, the greatest point of materialization (see Joscelyn Godwin, Arktos: The Polar Myth).

Robert Charroux first related the Hyperboreans to an ancient astronaut race of "reputedly very large, very white people" who had chosen "the least warm area on the earth because it corresponded more closely to their own climate on the planet from which they originated".[44] Miguel Serrano was influenced by Charroux's writings on the Hyperboreans.[45]

See also

Notes

- Pindar, Tenth Pythian Ode; translated by Richmond Lattimore.

- The History of Herodotus, parallel English/Greek: Book 4: Melpomene: 30

- Bridgman, Timothy P. (2005). Hyperboreans. Myth and history in Celtic-Hellenic contacts. London: Routledge. pp. 27–31. ISBN 0-415-96978-6.

- Phillips, E. D. (1955). "The Legend of Aristeas: Fact and Fancy in Early Greek Notions of East Russia, Siberia, and Inner Asia". Artibus Asiae. 18 (2): 161–177 [p. 166]. doi:10.2307/3248792. JSTOR 3248792.

- Bridgman, p. 31

- Bridgman, p. 61.

- Description of Greece, 5. 7. 8

- Aristeas of Proconnesus, Bolton, Oxford, 1962, p. 111

- Bridgman, p. 35, 72

- Bridgman, p. 45

- Bridgman, pp. 60–69.

- Meteorologica, 1. 13. 350b.

- Bridgman, pp. 75–80

- Supplementum Hellenistcum, Berlin, 1983, No. 906, 411.

- Bridgman, p. 79.

- Strabo, 11.4.3.

- Fridtjof Nansen.In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in Early Times. Frederick A. Stokes co., 1911. Page 188.

- Plutarch – Life of Camillus

- Bridgman, pp. 163–173.

- Bridgman, p. 86

- Stromata iv. xxi' Exhortation, II.

- Diodorus Siculus, Book II, 47–48

- Squire, Charles, Celtic Myth & Legend, p.42 ff. Squire's claim that Diodorus locates this temple "in the centre of Britain" is unfounded. Diodorus 2.47

- Lewis Spence, The Mysteries of Britain, 1905.

- Bridgman, p. 91

- Haycock, David Boyd (2002). "Chapter 7: Much Greater, Than Commonly Imagined.". William Stukeley: Science, Religion and Archaeology in Eighteenth-Century England. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9780851158648. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- Bezalel Bar-Kochva (1997), "The Structure of an Ethnographical Work", Pseudo-Hecataeus: On the Jews

- Drachmann, ed. (1910). Scholia Vetera in Pindari Carmina. Teubner. pp. II:249 (ad Pyth.10.70).

- Harris, J. Rendel (1925). "Apollo at the Back of the North Wind". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 45 (2): 229–242. doi:10.2307/625047. JSTOR 625047.

- Herodotus. Historia. Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved 17 May 2017. Book IV, 33–34

- Aelian. On the Nature of Animals. Loeb Classical Library. p. 357. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Bibliotheca Historica, II. 47

- Bridgman, pp.92–134

- Hymn IV to Delos, 292

- Bridgman, Timothy P. (2005), Hyperboreans: myth and history in Celtic-Hellenic contacts, Routledge, p. 76, ISBN 0-415-96978-6 – via Google Books

- See further Bridgman, Hyperboreans. Myth and history in Celtic-Hellenic contacts (2005).

- Book of Invasions 265 and 304-306

- Wasson, R.G.; Kramrisch, Stella; Ott, Jonathan; et al. (1986), Persephone's Quest – Entheogens and the origins of Religion, Yale University Press, pp. 227–230, ISBN 0-300-05266-9

- Davidson, Adventures in Unhistory: Conjectures on the Factual Foundations of Several Ancient Legends.

- Irving, Astoria or Anecdotes of an enterprise beyond the Rocky Mountains (1836).

- Bennett, John G (December 1963). "The Hyperborean Origin of the Indo-European Culture". Systematics. 1 (3). Archived from the original on 2011-09-14.

- Godwin, Jocelyn (1993). Arktos: the Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 32–50. ISBN 0-500-27713-3.

- Jeffrey, Jason (January–February 2000). "Hyperborea & the Quest for Mystical Enlightenment". New Dawn (58).

- Charroux, Robert (1974). The Mysterious Past. London: Futura Publications. p. 29. ISBN 0-86007-044-1.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (2003). Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-3155-4.

References

- Portions of this article were formerly excerpted from the public domain Lemprière's Classical Dictionary, 1848.

- Bridgman, Timothy M. (2005). Hyperboreans. Myth and history in Celtic-Hellenic contacts. Studies in Classics. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96978-6.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

_political.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)