Karakoram

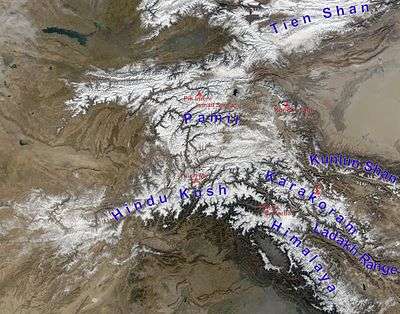

The Karakoram is a mountain range which although it spans the borders of India, Pakistan and China with the northwest extremity of the range extending to Afghanistan and Tajikistan, the highest 15 mountains are all based in Pakistan. It begins in the Wakhan Corridor (Afghanistan) in the west and encompasses the majority of Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan) and extends into Ladakh (India) and the disputed Aksai Chin region controlled by China. It is the second highest mountain range in the world and part of the complex of ranges including the Pamir Mountains, the Hindu Kush and the Himalayan Mountains.[1][2] The Karakoram has eight summits over 7,500 m (24,600 ft) height, with four of them exceeding 8,000 m (26,000 ft):[3] K2, the second highest peak in the world at 8,611 m (28,251 ft), Gasherbrum I, Broad Peak and Gasherbrum II.

| Karakoram | |

|---|---|

Baltoro glacier in the Central Karakoram, Pakistan | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | K2 Pakistan |

| Elevation | 8,611 m (28,251 ft) |

| Coordinates | 35°52′57″N 76°30′48″E |

| Geography | |

Karakoram and other ranges of Central Asia

| |

| Countries | |

| Regions | Gilgit-Baltistan, Ladakh, Xinjiang and Badakhshan |

| Range coordinates | 36°N 76°E |

| Borders on | List

|

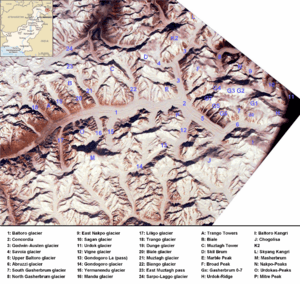

The range is about 500 km (311 mi) in length and is the most heavily glaciated part of the world outside the polar regions. The Siachen Glacier at 76 kilometres (47 mi) and the Biafo Glacier at 63 kilometres (39 mi) rank as the world's second and third longest glaciers outside the polar regions.[4]

The Karakoram is bounded on the east by the Aksai Chin plateau, on the northeast by the edge of the Tibetan Plateau and on the north by the river valleys of the Yarkand and Karakash rivers beyond which lie the Kunlun Mountains. At the northwest corner are the Pamir Mountains. The southern boundary of the Karakoram is formed, west to east, by the Gilgit, Indus and Shyok rivers, which separate the range from the northwestern end of the Himalaya range proper. These rivers flow northwest before making an abrupt turn southwestward towards the plains of Pakistan. Roughly in the middle of the Karakoram range is the Karakoram Pass, which was part of a historic trade route between Ladakh and Yarkand but now inactive.

The Tashkurghan National Nature Reserve and the Pamir Wetlands National Nature Reserve in the Karalorun and Pamir mountains have been nominated for inclusion in UNESCO in 2010 by the National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO and has tentatively been added to the list.[5]

Name

Karakoram is a Turkic term meaning black gravel. The Central Asian traders originally applied the name to the Karakoram Pass.[6] Early European travellers, including William Moorcroft and George Hayward, started using the term for the range of mountains west of the pass, although they also used the term Muztagh (meaning, "Ice Mountain") for the range now known as Karakoram.[6][7] Later terminology was influenced by the Survey of India, whose surveyor Thomas Montgomerie in the 1850s gave the labels K1 to K6 (K for Karakoram) to six high mountains visible from his station at Mount Haramukh in Kashmir.

In ancient Sanskrit texts (Puranas), the name Krishnagiri (black mountains) was used to describe the range.[8][9]

Exploration

Due to its altitude and ruggedness, the Karakoram is much less inhabited than parts of the Himalayas further east. European explorers first visited early in the 19th century, followed by British surveyors starting in 1856.

The Muztagh Pass was crossed in 1887 by the expedition of Colonel Francis Younghusband[10] and the valleys above the Hunza River were explored by General Sir George K. Cockerill in 1892. Explorations in the 1910s and 1920s established most of the geography of the region.

The name Karakoram was used in the early 20th century, for example by Kenneth Mason,[6] for the range now known as the Baltoro Muztagh. The term is now used to refer to the entire range from the Batura Muztagh above Hunza in the west to the Saser Muztagh in the bend of the Shyok River in the east.

Floral surveys were carried out in the Shyok River catchment and from Panamik to Turtuk village by Chandra Prakash Kala during 1999 and 2000.[11][12]

Geology and glaciers

The Karakoram is in one of the world's most geologically active areas, at the plate boundary between the Indo-Australian plate and the Eurasian plate.[13] A significant part, somewhere between 28 and 50 percent, of the Karakoram Range is glaciated covering an area of more than 15,000 square kilometres or 5,800 square miles[14], compared to between 8 and 12 percent of the Himalaya and 2.2 percent of the Alps.[15] Mountain glaciers may serve as an indicator of climate change, advancing and receding with long-term changes in temperature and precipitation. The Karakoram glaciers are slightly retreating,[16][17][18] unlike the Himalayas where glaciers are losing mass at significantly higher rate, many Karakoram glaciers are covered in a layer of rubble which insulates the ice from the warmth of the sun. Where there is no such insulation, the rate of retreat is high.[19]

The Karakoram during the Ice Age

In the last ice age, a connected series of glaciers stretched from western Tibet to Nanga Parbat, and from the Tarim basin to the Gilgit District.[20][21][22] To the south, the Indus glacier was the main valley glacier, which flowed 120 kilometres (75 mi) down from Nanga Parbat massif to 870 metres (2,850 ft) elevation.[20][23] In the north, the Karakoram glaciers joined those from the Kunlun Mountains and flowed down to 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) in the Tarim basin.[22][24]

While the current valley glaciers in the Karakoram reach a maximum length of 76 kilometres (47 mi), several of the ice-age valley glacier branches and main valley glaciers, had lengths up to 700 kilometres (430 mi). During the Ice Age, the glacier snowline was about 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) lower than today.[22][23]

Highest peaks

The highest peaks of the Karakoram are:

- K2: 8,611 metres (28,251 ft)

- Gasherbrum I: 8,080 metres (26,510 ft)

- Broad Peak: 8,051 metres (26,414 ft)

- Gasherbrum II: 8,035 metres (26,362 ft)

- Gasherbrum III: 7,952 metres (26,089 ft)

- Gasherbrum IV: 7,925 metres (26,001 ft)

- Distaghil Sar: 7,885 metres (25,869 ft)

- Kunyang Chhish: 7,852 metres (25,761 ft)

- Masherbrum I: 7,821 metres (25,659 ft)

- Batura I: 7,795 metres (25,574 ft)

- Rakaposhi: 7,788 metres (25,551 ft)

- Batura II: 7,762 metres (25,466 ft)

- Kanjut Sar: 7,760 metres (25,460 ft)

- Saltoro Kangri: 7,742 metres (25,400 ft)

- Batura III: 7,729 metres (25,358 ft)

- Saser Kangri: 7,672 metres (25,171 ft)

- Chogolisa: 7,665 metres (25,148 ft)

- Shispare Sar: 7,611 metres (24,970 ft)

- Passu Sar: 7,478 metres (24,534 ft)

- Malubiting: 7,458 metres (24,469 ft)

- Sia Kangri: 7,442 metres (24,416 ft)

- K12: 7,428 metres (24,370 ft)

- Skil Brum: 7,410 metres (24,310 ft)

- Haramosh Peak: 7,397 metres (24,268 ft)

- Ultar Peak: 7,388 metres (24,239 ft)

- Momhil Sar: 7,343 metres (24,091 ft)

- Baintha Brakk: 7,285 metres (23,901 ft)

- Baltistan Peak: 7,282 metres (23,891 ft)

- Muztagh Tower: 7,273 metres (23,862 ft)

- Diran: 7,266 metres (23,839 ft)

- Gasherbrum V: 7,147 metres (23,448 ft)

The majority of the highest peaks are in the Gilgit–Baltistan region of Pakistan. Baltistan has more than 100 mountain peaks exceeding 6,100 metres (20,000 ft) height from sea level.

K-numbers

- K1: Masherbrum

- K2: an unnamed 8,611m peak at the head of the Godwin-Austen Glacier

- K3: Gasherbrum IV

- K3a: Gasherbrum III

- K4: Gasherbrum II

- K5: Gasherbrum I

- K6: Baltistan Peak

- K7: an unnamed 6,934m peak at the head of the Charakusa Valley

- K8: an unnamed 7,422m peak on the western flank of the Siachen Glacier

- K9: an unnamed 7,000m (approx) peak near Trango Towers

- K10: Saltoro Kangri I

- K11: Saltoro Kangri II

- K12: an unnamed 7,428m subsidiary peak of Saltoro Kangri

- K13: Dansam 6,666m peak south west of Saltoro Kangri

- K22: Saser Kangri I

- K25: Pastan Kangri 6,523m peak south of the Saltoro group

- K35: Mamostong Kangri

Subranges

The naming and division of the various subranges of the Karakoram is not universally agreed upon. However, the following is a list of the most important subranges, following Jerzy Wala.[25] The ranges are listed roughly west to east.

Passes

From west to east

- Kilik Pass

- Mintaka Pass

- Khunjerab Pass (the highest paved international border crossing at 4,693 m (15,397 ft))

- Shimshal Pass

- Mustagh Pass

- Karakoram Pass

- Sasser Pass

- Naltar Pass or Pakora Pass[26]

The Khunjerab Pass is the only motorable pass across the range. The Shimshal Pass (which does not cross an international border) is the only other pass still in regular use.

Cultural references

The Karakoram mountain range has been referred to in a number of novels and movies. Rudyard Kipling refers to the Karakoram mountain range in his novel Kim, which was first published in 1900. Marcel Ichac made a film titled Karakoram, chronicling a French expedition to the range in 1936. The film won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival of 1937. Greg Mortenson details the Karakoram, and specifically K2 and the Balti, extensively in his book Three Cups of Tea, about his quest to build schools for children in the region. In the Gatchaman TV series, the Karakoram range houses Galactor's headquarters. K2 Kahani (The K2 Story) by Mustansar Hussain Tarar describes his experiences at K2 base camp.[27]

See also

- Karakoram Highway

- List of mountain ranges of the world

- List of highest mountains (a list of mountains above 7,200 m (23,600 ft))

- Mount Imeon

- Naltar Valley

- Trans-Karakoram Tract

Notes

- Bessarabov, Georgy Dmitriyevich (7 February 2014). "Karakoram Range". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- "Hindu Kush Himalayan Region". ICIMOD. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Shukurov, The Natural Environment of Central and South Asia 2005, p. 512; Voiland, Adam (2013). "The Eight-Thousanders". Nasa Earth Observatory. Retrieved 23 December 2016.; BBC, Planet Earth, "Mountains", Part Three

- Tajikistan's Fedchenko Glacier is 77 kilometres (48 mi) long. Baltoro and Batura Glaciers in the Karakoram are 57 kilometres (35 mi) long, as is Bruggen or Pio XI Glacier in southern Chile. Measurements are from recent imagery, generally supplemented with Russian 1:200,000 scale topographic mapping as well as Jerzy Wala,Orographical Sketch Map: Karakoram: Sheets 1 & 2, Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich, 1990.

- "Karakorum-Pamir". unesco. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Mason, Kenneth (1928). Exploration of the Shaksgam Valley and Aghil ranges, 1926. p. 72. ISBN 9788120617940.

- Close C, Burrard S, Younghusband F, et al. (1930). "Nomenclature in the Karakoram: Discussion". The Geographical Journal. Blackwell Publishing. 76 (2): 148–158. doi:10.2307/1783980. JSTOR 1783980.

- Raza, Moonis; Ahmad, Aijazuddin; Mohammad, Ali (1978), The Valley of Kashmir: The land, Vikas Pub. House, p. 2, ISBN 978-0-7069-0525-0

- Chatterjee, Shiba Prasad (2004), Selected Works of Professor S.P. Chatterjee, Volume 1, National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organisation, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, p. 139

- French, Patrick. (1994). Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer, pp. 53, 56-60. HarperCollinsPublishers, London. Reprint (1995): Flamingo. London. ISBN 0-00-637601-0.

- Kala, Chandra Prakash (2005). "Indigenous Uses, Population Density, and Conservation of Threatened Medicinal Plants in Protected Areas of the Indian Himalayas". Conservation Biology. 19 (2): 368–378. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00602.x.

- Kala, Chandra Prakash (2005). "Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India" (PDF). Current Science. 89 (8): 1331.

- "Geological evolution of the Karakoram ranges". Italian Journal of Geosciences. 130: 147–159. 2011. doi:10.3301/IJG.2011.08.

- Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide; Khan, Asif (2019). "Early twenty-first century glacier mass losses in the Indus Basin constrained by density assumptions". Journal of Hydrology. 574: 467–475. Bibcode:2019JHyd..574..467M. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.04.057.

- Gansser (1975). Geology of the Himalayas. London: Interscience Publishers.

- Gallessich, Gail (2011). "Debris on certain Himalayan glaciers may prevent melting". sciencedaily.com. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide (2016). "Changes in the ablation zones of glaciers in the western Himalaya and the Karakoram between 1972 and 2015". Remote Sensing of Environment. 187: 505–512. Bibcode:2016RSEnv.187..505M. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2016.10.034.

- Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide; Nüsser, Marcus (2019). "No significant mass loss in the glaciers of Astore Basin (North-Western Himalaya), between 1999 and 2016". Journal of Glaciology. 65 (250): 270–278. Bibcode:2019JGlac..65..270M. doi:10.1017/jog.2019.5.

- Veettil, B.K. (2012). "A Remote sensing approach for monitoring debris-covered glaciers in the high altitude Karakoram Himalayas". International Journal of Geomatics and Geosciences. 2 (3): 833–841.

- Kuhle, M. (1988). "The Pleistocene Glaciation of Tibet and the Onset of Ice Ages- An Autocycle Hypothesis.Tibet and High Asia. Results of the Sino-German Joint Expeditions (I)". GeoJournal. 17 (4): 581–596. doi:10.1007/BF00209444.

- Kuhle, M. (2006). "The Past Hunza Glacier in Connection with a Pleistocene Karakoram Ice Stream Network during the Last Ice Age (Würm)". In Kreutzmann, H.; Saijid, A. (eds.). Karakoram in Transition. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press. pp. 24–48.

- Kuhle, M. (2011). "The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and Last Glacial Maximum) Ice Cover of High and Central Asia, with a Critical Review of Some Recent OSL and TCN Dates". In Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L.; Hughes, P.D. (eds.). Quaternary Glaciation - Extent and Chronology, A Closer Look. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV. pp. 943–965. (glacier maps downloadable)

- Kuhle, M. (2001). "Tibet and High Asia (VI): Glaciogeomorphology and Prehistoric Glaciation in the Karakoram and Himalaya". GeoJournal. 54 (1–4): 109–396. doi:10.1023/A:1021307330169.

- Kuhle, M. (1994). "Present and Pleistocene Glaciation on the North-Western Margin of Tibet between the Karakoram Main Ridge and the Tarim Basin Supporting the Evidence of a Pleistocene Inland Glaciation in Tibet. Tibet and High Asia. Results of the Sino-German and Russian-German Joint Expeditions (III)". GeoJournal. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer. 33 (2/3): 133–272. doi:10.1007/BF00812877.

- Jerzy Wala, Orographical Sketch Map of the Karakoram, Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich, 1990.

- shuaib (2019-08-18). "Naltar Valley: Heaven on Earth". Mehmaan Resort. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- Tarar, Mustansar Hussain (1994). K2 kahani. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel (published in Urdu). p. 179. ISBN 9693505239. OL 18941738M.

References

- Curzon, George Nathaniel. 1896. The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus. Royal Geographical Society, London. Reprint: Elibron Classics Series, Adamant Media Corporation. 2005. ISBN 1-4021-5983-8 (pbk); ISBN 1-4021-3090-2 (hbk).

- Kipling, Rudyard 2002. Kim (novel); ed. by Zohreh T. Sullivan. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 039396650X—This is the most extensive critical modern edition with footnotes, essays, maps, etc.

- Mortenson, Greg and Relin, David Oliver. 2008. Three Cups of Tea. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-103426-3 (pbk); Viking Books ISBN 978-0-670-03482-6 (hbk); Tantor Media ISBN 978-1-4001-5251-3 (MP3 CD).

- Kreutzmann, Hermann, Karakoram in Transition: Culture, Development, and Ecology in the Hunza Valley, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-547210-3

- Shukurov, E. (2005), "The Natural Environment of Central and South Asia" (PDF), in Chahryar Adle (ed.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. VI – Towards the contemporary period: from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century, UNESCO, pp. 480–514, ISBN 978-92-3-103985-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Blankonthemap The Northern Kashmir Website

- Pakistan's Northern Areas dilemma

- Great Karakorams