Slave Coast of West Africa

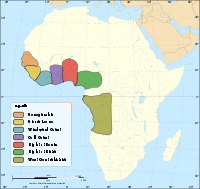

The Slave Coast is a historical name formerly used for that part of coastal West Africa along the Bight of Benin that is located between the Volta River and the Lagos Lagoon.[1] The name is derived from the region's history as a major source of Africans that were taken into slavery during the Atlantic slave trade from the early 16th century to the late 19th century. Other nearby coastal regions historically known by their prime colonial export are the Gold Coast, the Ivory Coast (or Windward Coast), and the Pepper Coast (or Grain Coast).

.jpg)

History

European sources began documenting the development of trade in this region and its integration into the trans-Atlantic slave trade around 1670. The slave trade became so extensive in the 18th and 19th centuries that an "Atlantic community" was formed.[2] The slave trade was facilitated on the European end by the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the British. Slaves went to the New World, mostly to Brazil and the Caribbean. Ports that exported these slaves from Africa include Ouidah, Lagos, Aného (Little Popo), Grand-Popo, Agoué, Jakin, Porto-Novo, and Badagry. These ports traded in slaves that were supplied from African communities, tribes and kingdoms, including the Alladah and Ouidah, which were later taken over by the Dahomey kingdom.

Researchers estimate that between two and three million people were stolen out of this region and traded for goods like alcohol and tobacco from the Americas and textiles from Europe. Current estimates are that about 12 million Africans were shipped across the Atlantic from West Africa, although the number purchased by traders was considerably higher.[3][4][5]

The coast was called "the White man's grave" due to the mass amount of death from illnesses such as yellow fever, malaria, heat exhaustion, and many gastro-entero sicknesses. In 1841, 80% of British sailors on expeditions up the Niger river were infected with fevers.[6] Between 1844 and 1854, 20 of the 74 French missionaries in Senegal died from local illnesses and 19 more died shortly after arriving back to France.[7][8]

Intermarriage has been documented in ports like Ouidah where Europeans were permanently stationed. Communication was quite extensive between all three areas of trade, to the point where even individual slaves could be tracked.[9]

This complex exchange fostered political and cultural as well as commercial connections between these three regions. Religions, architectural styles, languages, knowledge, and other new goods were mingled at this time. In addition to the slaves, free men used the exchange routes to travel to new places, and both slaves and free travellers aided in blending European and African cultures.

After slavery was abolished by European countries, the slave trade continued for a time with independent traders instead of government agents.

Cultural integration had become so extensive that the defining characteristics of each culture were increasingly broadened. In the case of Brazilian culture—which had differentiated itself from Portuguese culture through its combination of African, Portuguese and New World traditions—Brazilian-style dress, cuisine and speaking Portuguese had become the main requirements for Brazilian identity, regardless of ethnicity, religion, or geographic location.[10]

References and sources

- References

- Robin Law, "Slave-Raiders and Middlemen, Monopolists and Free-Traders: The Supply of Slaves for the Atlantic Trade in Dahomey c. 1715-1850", The Journal of African History, Vol. 30, No. 1 (1989), p. 46

- Law, Robin. The Slave Coast of West Africa 1550–1750: The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on an African Society. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991. p. 307.

- Ronald Segal, The Black Diaspora: Five Centuries of the Black Experience Outside Africa (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), ISBN 0-374-11396-3, p. 4. "It is now estimated that 11,863,000 slaves were shipped across the Atlantic." (Note in original: Paul E. Lovejoy, "The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa: A Review of the Literature", in Journal of African History 30 (1989), p. 368.)

- Eltis, David and Richardson, David, "The Numbers Game". In: Northrup, David: The Atlantic Slave Trade, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 2002, p. 95.

- Basil Davidson. The African Slave Trade.

- Curtin, Philip D. (1998). Disease and empire : the health of European troops in the conquest of Africa. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521591694. OCLC 39169947.

- Cohen, William B., 1941- (1971). Rulers of empire: the French colonial service in Africa. [Stanford, Calif.]: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 0817919511. OCLC 215926.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- James, Lawrence, 1943- (2017-06-06). Empires in the sun : the struggle for the mastery of Africa (First Pegasus books hardcover ed.). New York. ISBN 9781681774633. OCLC 959869470.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Law, Robin. The Slave Coast of West Africa 1550–1750: The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on an African Society. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991. p. 319.

- Law, Robin. The Slave Coast of West Africa 1550–1750: The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on an African Society. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991. p. 327.

7. Anissa Smith

- Sources

- Law, Robin and Kristin Mann. "African and American Atlantic Worlds". The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Ser., 56:2 Apr. 1999, pp. 307–334.

- Shillington, Kevin. History of Africa. 2nd Edition, Macmillan Publishers Limited, NY USA, 2005.

- St Clair, William. The Door of No Return: The History of Cape Coast Castle and the Atlantic Slave Trade. BlueBridge.