Celtic Sea

The Celtic Sea (Irish: An Mhuir Cheilteach; Welsh: Y Môr Celtaidd; Cornish: An Mor Keltek; Breton: Ar Mor Keltiek; French: La mer Celtique) is the area of the Atlantic Ocean off the south coast of Ireland bounded to the east by Saint George's Channel;[1] other limits include the Bristol Channel, the English Channel, and the Bay of Biscay, as well as adjacent portions of Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. The southern and western boundaries are delimited by the continental shelf, which drops away sharply. The Isles of Scilly are an archipelago of small islands in the sea.

| Celtic Sea | |

|---|---|

Celtic Sea in July 2011 | |

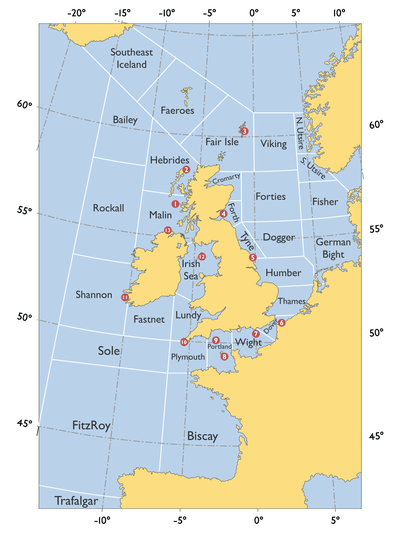

Bathymetric map of the Celtic Sea, part of the Atlantic Ocean, and its surroundings | |

| Coordinates | 50°N 8°W |

| Type | Sea |

| Basin countries | Ireland, England, Wales, France |

History

The Celtic Sea receives its name from the Celtic heritage of the bounding lands to the north and east.[2] The name was first proposed by E. W. L. Holt at a 1921 meeting in Dublin of fisheries experts from Great Britain, France, and Ireland.[2] The northern portion of this sea was considered as part of Saint George's Channel and the southern portion as an undifferentiated part of the "Southwest Approaches" to Great Britain. The desire for a common name came to be felt because of the common marine biology, geology and hydrology of the area.[2] It was adopted in France before being common in the English-speaking countries;[2] in 1957 Édouard Le Danois wrote, "the name Celtic Sea is hardly known even to oceanographers."[3] It was adopted by marine biologists and oceanographers, and later by petroleum exploration firms.[4] It is named in a 1963 British atlas,[5] but a 1972 article states "what British maps call the Western Approaches, and what the oil industry calls the Celtic Sea [...] certainly the residents on the western coast [of Great Britain] don't refer to it as such."[6]

Limits

There are no land features to divide the Celtic Sea from the open Atlantic Ocean to the south and west. For these limits, Holt suggested the 200-fathom (370 m; 1,200 ft) marine contour and the island of Ushant off the tip of Brittany.

The definition approved by 1974 by the UK Hydrographer of the Navy for use in Admiralty Charts was "bounded roughly by lines joining Ushant, Land's End, Hartland Point, Lundy Island, St. Govan's Head and Rosslare, thence following the Irish coast south to Mizen Head and then along the 200-metre isobath to approximately the latitude of Ushant."[7]

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Celtic Sea as follows:[8]

On the North. The Southern limit of the Irish Sea [a line joining St David's Head to Carnsore Point], the South coast of Ireland, thence from Mizen Head a line drawn to a position 51°0′N 11°30′W.

On the West and South. A line from the position 51°0′N 11°30′W South to 49°N, thence to latitude 46°30'N on the Western limit of the Bay of Biscay [a line joining Cape Ortegal to Penmarch Point], thence along that line to Penmarch Point.

On the East. The Western limit of the English Channel [a line joining Île Vierge to Land's End] and the Western limit of the Bristol Channel [a line joining Hartland Point to St. Govan's Head].

Seabed

The seabed under the Celtic Sea is called the Celtic Shelf, part of the continental shelf of Europe. The northeast portion has a depth of between 90 and 100 m (300–330 ft), increasing towards Saint George's Channel. In the opposite direction, sand ridges pointing southwest have a similar height, separated by troughs approximately 50 m (160 ft) deeper. These ridges were formed by tidal effects when the sea level was lower. South of 50°N the topography is more irregular.[9]

Oil and gas exploration in the Celtic Sea has had limited commercial success. The Kinsale Head gas field supplied much of the Republic of Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s. The water is too deep for fixed wind turbines. The area has potential for 50 GW of floating wind farms, and Total S.A. plans a project with almost 100 MW.[10]

Ecology of the Celtic Sea

The Celtic Sea has a rich fishery with total annual catches of 1.8 million tonnes as of 2007.[11]

Four cetacean species occur frequently in the area: minke whale, bottlenose dolphin, short-beaked common dolphin and harbor porpoise.[12] Formerly, it held an abundance of marine mammals.[13][14]

References

- C. Michael Hogan. 2011. Celtic Sea. eds. P. Saundry & C. Cleveland. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the /environment. Washington DC.

- Haslam, D. W. (Hydrographer of the Royal Navy) (29 March 1976). "It's the Celtic Sea—official". The Times (59665). p. 15 (Letters to the Editor), col G.

- Le Danois, Edouard (1957). Marine Life of Coastal Waters: Western Europe. Harrap. p. 12.

- Cooper, L. H. N. (2 February 1972). "In Celtic waters". The Times (58391). p. 20; col G (Letters to the Editor).

- The Atlas of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Clarendon Press. 1963. pp. 20–21.; cited in

Shergold, Vernon G. (27 January 1972). "Celtic Sea: a good name". The Times (58386). p. 20 (Letters to the Editor); col G. - Vielvoye, Roger (24 January 1972). "Industry in the regions Striking oil in Wales and West Country". The Times (58383). p. 19; col A.

- "Celtic Sea". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 883. House of Commons. 16 December 1974. col. 317W.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition + corrections" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1971. p. 42 [corrections to page 13]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Hardisty, Jack (1990). The British Seas: an introduction to the oceanography and resources of the north-west European continental shelf. Taylor & Francis. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-415-03586-4.

- Snieckus, Darius (19 March 2020). "Oil giant Total dives into offshore wind with 'world's biggest' floating array". Recharge | Latest renewable energy news. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020.

- European Union. "Celtic Seas". European Atlas of the Seas. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Hammond, P. S.; Northridge, S. P.; Thompson, D.; Gordon, J. C. D. (2008). "1 Background information on marine mammals for Strategic Environmental Assessment 8" (PDF). Sea Mammal Research Unit. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Van Deinse, A. B.; Junge, G. C. A. (1936). "Recent and older finds of the California grey whale in the Atlantic". Temminckia. 2: 161–88.

- Fraser, F. C. (1936). "Report on cetacea stranded on the British Coasts from 1927 to 1932". British Museum (Natural History) No. 11, London, UK.

External links

- Coccoliths in the Celtic Sea : a bloom of phytoplankton in the Celtic Sea, visible from outer space in an MISR image, 4 June 2001