Volhynia

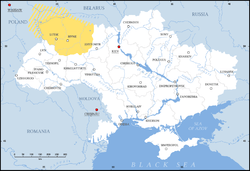

Volhynia (/voʊˈlɪniə/; Polish: Wołyń, Ukrainian: Волинь, romanized: Volyń), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, situated between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. While the borders of the region are not clearly defined, the territory that still carries the name is Volyn Oblast, located in western Ukraine. Volhynia has changed hands numerous times throughout history and been divided among competing powers. At one time all of Volhynia was part of the Pale of Settlement designated by Imperial Russia on its southwestern-most border.

Volhynia Волинь | |

|---|---|

Lubart's Castle (Lutsk) was the seat of the medieval princes of Volhynia. | |

Coat of arms | |

Volhynia (yellow) in modern Ukraine | |

| Coordinates: 50°44′42.0″N 25°21′13.7″E | |

| Country | Poland, Belarus, Ukraine |

| Region | Southeastern Poland, Southwestern Belarus, Western Ukraine |

| Parts | Volyn Oblast, Rivne Oblast, Zhytomyr Oblast, Ternopil Oblast, Khmelnytskyi Oblast, Lublin Voivodeship, Brest Region |

Important cities include Lutsk, Rivne, Volodymyr-Volynskyi (Volodymyr), Iziaslav, and Novohrad-Volynskyi (Zviahel). After the annexation of Volhynia by the Russian Empire as part of the Partitions of Poland, it also included the cities of Zhytomyr, Ovruch, Korosten. The city of Zviahel was renamed Novohrad-Volynsky, and Volodymyr became Volodymyr-Volynskyi.

Names and etymology

Volynia Ukrainian: Волинь, romanized: Volyń); Polish: Wołyń, Lithuanian: Voluinė or Volynė; Czech: Volyň, Hungarian: Volhínia, German: Wolhynien [vo.ˈlyː.ni̯ən] or Wolynien [vo.ˈlyː.ni̯ən] (Volhynian German: Wolhynien/Wolhinien [vo.ˈliː.ni̯ən] or Wolynien/Wolinien [vo.ˈliː.ni̯ən]), Yiddish: װאָלין, romanized: Volin)

The alternative name for the region is Lodomeria after the city of Volodymyr-Volynsky (previously known as Volodymer), which was once a political capital of the medieval Volhynian Principality.

According to some historians, the region is named after a semi-legendary city of Volin or Velin, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River,[1] whose name may come from the Proto-Slavic root *vol/vel- 'wet'. In other versions, the city was located over 20 km (12 mi) to the west of Volodymyr-Volynskyi near the mouth of the Huczwa River, a tributary of the Western Bug.

Geography

Geographically it occupies northern areas of the Volhynian-Podolian Upland and western areas of Polesian Lowland along the Prypyat valley as part of the vast East European Plain, between the Western Bug in the west and upper streams of Uzh and Teteriv rivers.[2] Before the partitions of Poland, the eastern edge stretched a little west along the right-banks of the Sluch River or just east of it. Within the territory of Volhynia is located Little Polisie, a lowland that actually divides the Volhynian-Podolian Upland into separate Volhynian Upland and northern outskirts of Podolian Upland, the so-called Kremenets Hills. Volhynia is located in the basins of the Western Bug and Prypyat, therefore most of its rivers flow either in a northern or a western direction.

Relative to other historical regions, it is northeast of Galicia, east of Lesser Poland and northwest of Podolia. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, and it is often considered to overlap a number of other regions, among which are Polesia and Podlasie.

The territories of historical Volhynia are now part of the Volyn, Rivne and parts of the Zhytomyr, Ternopil and Khmelnytskyi Oblasts of Ukraine, as well as parts of Poland (see Chełm). Major cities include Lutsk, Rivne, Kovel, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Kremenets (Ternopil Oblast) and Starokostiantyniv (Khmelnytskyi Oblast). Before World War II, many Jewish shtetls (villages), such as Trochenbrod and Lozisht, were an integral part of the region.[3] At one time all of Volhynia was part of the Pale of Settlement designated by Imperial Russia on its southwesternmost border.[4]

History

The land was mentioned in the works of Arabian scholar Al-Masudi, who denoted the local tribe as "people of Valin". In his work of 947–948, Al-Masudi mentions the Valinians as an intertribal union ruled by their leader Madjak.

Volhynia may have been included (or was in the sphere of influence) in the Grand Duchy of Kiev (Ruthenia) as early as the 10th century. At that time Princess Olga sent a punitive raid against the Drevlians to avenge the death of her husband Grand Prince Igor (Ingvar Röreksson); she later established pogosts along the Luha River. In the opinion of the Ukrainian historian Yuriy Dyba, the chronicle phrase «и оустави по мьстѣ. погосты и дань. и по лузѣ погосты и дань и ѡброкы» (and established in place pogosts and tribute along Luha (лузѣ), the path of pogosts and tribute reflects the actual route of Olga's raid against the Drevlians further to the west, up to the Western Bug's right tributary Luha River.

As early as 983, Vladimir the Great appointed his son Vsevolod as the ruler of the Volhynian Principality. In 988 he established the city of Volodymer (Володимѣръ).

The first records can be traced to the Ruthenian chronicles, such as the Primary Chronicle, which mentions tribes of the Dulebe, Buzhan and Volhynian peoples in the year of 1077.

Volhynia's early history coincides with that of the duchies or principalities of Halych and Volhynia. These two successor states of the Kievan Rus formed Halych-Volhynia between the 12th and the 14th centuries.

After the disintegration of the Grand Duchy of Halych-Volhynia circa 1340, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania divided the region between them, Poland taking Western Volhynia and Lithuania taking Eastern Volhynia (1352–1366). After 1569 Volhynia was organized as a province of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During this period many Poles and Jews settled in the area. The Roman and Greek Catholic churches became established in the province. In 1375 a Roman Catholic Diocese of Lodomeria was established, but it was suppressed in 1425. Many Orthodox churches joined the latter organization in order to benefit from a more attractive legal status. Records of the first agricultural colonies of Mennonites, Protestants from Germany, date from 1783.

After the Third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, Volhynia was annexed as the Volhynian Governorate of the Russian Empire. It covered an area of 71,852.7 square kilometres. Following this annexation, the Russian government greatly changed the religious make-up of the area: it forcibly liquidated the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, transferring all of its buildings to the ownership and control of the Russian Orthodox Church. Many Roman Catholic church buildings were also given to the Russian Church. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Lutsk was suppressed by order of Empress Catherine II.

In 1897, the population amounted to 2,989,482 people (41.7 per square kilometre). It consisted of 73.7 percent East Slavs (predominantly Ukrainians), 13.2 percent Jews, 6.2 percent Poles, and 5.7 percent Germans.[5] Most of the German settlers had immigrated from Congress Poland. A small number of Czech settlers also had migrated here. Although economically the area was developing rather quickly, upon the eve of the First World War it was still the most rural province in Western Russia.

World War I and the German settlements in Volhynia

Ukrainian Nationalist at the end of World War I

At the end of the First World War, nationalists tried to form the Ukrainian National Autonomy. The territory of Volhynia was split in half by a frontline just west of the city of Lutsk. Due to an invasion of the Bolsheviks, the government of Ukraine was forced to retreat to Volhynia after the sack of Kiev. Military aid from the Central Powers brought peace in the region and some degree of stability. Until the end of the war, the area saw a revival of Ukrainian culture after years of Russian oppression and the denial of Ukrainian traditions. After German troops were withdrawn, the whole region was engulfed by a new wave of military actions by Poles and Russians competing for control of the territory. Ukraine was forced to fight on three fronts - Bolsheviks, Poles and a Volunteer Army of Imperial Russia.

Post World War I

In 1921, after the end of the Polish–Soviet war, the treaty known as the Peace of Riga divided the Volhynian Governorate between Poland and the Soviet Union. Poland took the larger part and established Volhynian Voivodeship.

Most of eastern Volhynian Governorate became part of the Ukrainian SSR, eventually being split into smaller districts. During that period, a number of national districts were formed within the Soviet Ukraine as part of cultural liberalization. The policies of Polonization in Poland led to formations of various resistance movements in West Ukraine and West Belarus, including Volhynia. In 1931 the Vatican of the Roman Catholic Church established a Ukrainian Catholic Apostolic Exarchate of Volhynia, Polesia and Pidliashia (Wolhynien, Polissia und Pidliashia in German), where the congregation practiced the Byzantine Rite in Ukrainian language.

From 1935 to 1938 the government of the Soviet Union deported numerous nationals from Volhynia in a population transfer to Siberia and central Asia, as part of the dekulakization, an effort to suppress peasant farmers in the region. These people included Poles of Eastern Volhynia (see Population transfer in the Soviet Union).

World War II

Following the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 and the subsequent invasion and division of Polish territories between the Reich and the USSR, the Soviet Union invaded and occupied the Polish part of Volhynia. In the course of the Nazi–Soviet population transfers which followed this (temporary) German-Soviet alliance, most of the ethnic German-minority population of Volhynia were transferred to those Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany. Following the mass deportations and arrests carried out by the NKVD, and repressive actions against Poles taken by Germany: deportation to the Reich to forced labour camps, arrests, detention in camps and mass executions, by 1943 ethnic Poles constituted only 10–12% of the entire population of Volhynia.

During the German invasion, around 40,000–60,000 Polish people in Volhynia were massacred by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The number of Ukrainian victims of Polish retaliatory attacks until the spring of 1945 is estimated at approx. 2,000−3,000 in Volhynia.[6] In 1945 Soviet Ukraine expelled ethnic Germans from Volhynia following the end of the war, because Nazi Germany had used ethnic Germans in eastern Europe as an excuse to invade those areas. The expulsion of Germans from eastern Europe was part of a mass population transfer after the war.

Soviet Ukraine annexed Volhynia after the end of World War II. In 1944 the communists in Volyhnia suppressed the Ukrainian Catholic Apostolic Exarchate. Most of the remaining ethnic Polish population were expelled to Poland in 1945. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, Volhynia has been an integral part of Ukraine.

Important relics

Notable residents

- Moisey Kasyanik, weightlifter

- Malbim, rabbi

- Hayim Nahman Bialik, literary figure

See also

- Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia

- Galicia (Eastern Europe)

- Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

- Historiography of the Volyn tragedy

- Polish Autonomous District

- Kresy Wschodnie

References

- E.M. Pospelov, Geograficheskie nazvaniya mira (Moscow, 1998), p. 104.

- Portnov, A. Volyn. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine.

- Michael Jones (2000). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press. p. 770. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- Oreck, Alden. "Jewish Virtual Library-The Pale of Settlement". Jewish Virtual Library. Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. 6th edition, Vol. 20, Leipzig and Vienna" 1909, pp. 744-745.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-12-24. Retrieved 2014-12-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Literature

- Jan Potocki Histoire anciènne du gouvernement de Volhynie : pour servir de suite à l'histoire primitive des peuples de la Russie, Sankt Petersbourg, 1805

- Andriyashev Alexander (1887) (in Russian) Essay of the History of Volyn land (Очерк истории Волынской земли) at Runivers.ru in Djvu and PDF formats

- Kathryn Ciancia, "Borderland Modernities: Poles, Jews and Urban Spaces in Interwar Volhynia," Journal of Modern History, forthcoming 2016.

- Ulrich Merten, Voices from the Gulag: Oppression of the German Minority in the Soviet Union, (American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2015) ISBN 978-0-692-60337-6

- Central European Superpower, Henryk Litwin, BUM Magazine, October 2016.

External links

| Look up Volyn in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Volhynia. |

- The Journey to Trochenbrod and Lozisht aug 2006

- Imperial Russian Volhynia District Map

- Swiss-Volhynian Mennonites

- Germans in Volhynia - English

- Germans in Volhynia - Another English site

- Germans in Volhynia - German

- GCatholic - Latin diocese of Lodomeria

- GCatholic - Ukrainian Apostolic Exarchate

- Volhynia-Galicia (in Polish)

- American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, Lincoln, Nebraska