Puncak Jaya

Puncak Jaya (Indonesian: [ˈpuntʃak ˈdʒaja]) or Carstensz Pyramid (4,884 m [16,024 ft]) is the highest summit of Mount Jayawijaya or Mount Carstensz /ˈkɑːrstəns/ in the Sudirman Range of the western central highlands of Papua Province, Indonesia (within Puncak Jaya Regency). Other summits are East Carstensz Peak (4,808 m [15,774 ft]), Sumantri (4,870 m [15,980 ft]) and Ngga Pulu (4,863 m [15,955 ft]). Other names include Nemangkawi in the Amungkal language, Carstensz Toppen and Gunung Soekarno.[2]

| Puncak Jaya | |

|---|---|

| Carstensz Pyramid | |

Peak of Puncak Jaya | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 4,884 m (16,024 ft) [1] |

| Prominence | 4,884 m (16,024 ft) Ranked 9th |

| Isolation | 5,262 km (3,270 mi) |

| Listing | Seven Summits Country high point Ultra Ribu |

| Coordinates | 04°04′44″S 137°9′30″E |

| Geography | |

Puncak Jaya Papua Province, Indonesia | |

| Parent range | Sudirman Range |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1936 by Colijn, Dozy, and Wissels 1962 by Harrer, Temple, Kippax and Huizenga |

| Easiest route | rock/snow/ice climb |

At 4,884 metres (16,024 ft) above sea level, Puncak Jaya is the highest mountain in Indonesia, on the island of New Guinea.

It is also the highest point between the Himalayas and the Andes. Some sources claim Papua New Guinea's Mount Wilhelm, 4,509 m (14,793 ft), as the highest mountain peak in Oceania, on account of Indonesia being part of Asia (Southeast Asia).[3] The massive, open cut Grasberg mine is within 4 km (2.5 mi) west of here.

History

European Discovery

The highlands surrounding the peak were inhabited before European contact, and the peak was known as Nemangkawi in Amungkal. Puncak Jaya was named "Carstensz Pyramid" after Dutch explorer Jan Carstenszoon, who was the first European who sighted the glaciers on the peak of the mountain on a rare clear day in 1623.[4] The sighting went unverified for over two centuries, and Carstensz was ridiculed in Europe when he said he had seen snow near the equator.

The snowfield of Puncak Jaya was reached as early as 1909 by a Dutch explorer, Hendrik Albert Lorentz with six of his Dayak Kenyah porters recruited from the Apo Kayan in Borneo.[5] The predecessor of the Lorentz National Park, which encompasses the Carstensz Range, was established in 1919 following the report of this expedition.

Climbing history

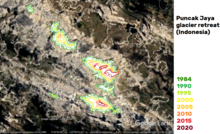

In 1936, the Dutch Carstensz Expedition, unable to establish definitively which of the three summits was the highest, attempted to climb each. Anton Colijn, Jean Jacques Dozy and Frits Wissel reached both the glacier-covered East Carstensz and Ngga Pulu summits on December 5th, but, due to bad weather, failed in their attempts to climb the bare Carstensz Pyramid. Because of extensive snow melt Ngga Pulu has become a 4,862 m (15,951 ft) subsidiary peak, but it has been estimated that in 1936 (when glaciers still covered 13 km2 (5.0 sq mi) of the mountain; see map) Ngga Pulu was indeed the highest summit, reaching over 4,900 m (16,100 ft).[6]

The now-highest Carstensz Pyramid summit was not climbed until 1962, by an expedition led by the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer (of Seven Years in Tibet fame, and climber of the Eiger North Face) with three other expedition members – the New Zealand mountaineer Philip Temple, the Australian rock climber Russell Kippax, and the Dutch patrol officer Albertus (Bert) Huizenga. Temple had previously led an expedition into the area and pioneered the access route to the mountains.[7]

When Indonesia took control of the province in 1963, the peak was renamed 'Poentja Soekarno' (Simplified Indonesian: Puncak Sukarno) or Sukarno Peak, after the first President of Indonesia; later this was changed to Puncak Jaya. Puncak means peak or mountain and Jaya means 'victory', 'victorious' or 'glorious'. The name Carstensz Pyramid is still used among mountaineers.[8]

Geology

Puncak Jaya is the highest point on the central range, which was created in the late Miocene Melanesian orogeny,[9] caused by oblique collision between the Australian and Pacific plates and is made of middle Miocene limestones.[10]

Access

Access to the peak requires a government permit. The mountain was closed to tourists and climbers between 1995 and 2005. As of 2006, access is possible through various adventure tourism agencies.[11]

Glaciers

While Puncak Jaya's peak is free of ice, there are several glaciers on its slopes, including the Carstensz Glacier, West Northwall Firn, East Northwall Firn and the recently vanished Meren Glacier in the Meren Valley (meren is Dutch for "lakes").[12] Being equatorial, there is little variation in the mean temperature during the year (around 0.5 °C [0.90 °F]) and the glaciers fluctuate on a seasonal basis only slightly. However, analysis of the extent of these rare equatorial glaciers from historical records show significant retreat since the 1850s, around the time of the Little Ice Age Maximum which primarily affected the Northern Hemisphere, indicating a regional warming of around 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) per century between 1850 and 1972.

The glacier on Puncak Trikora in the Maoke Mountains disappeared completely some time between 1939 and 1962.[13] Since the 1970s, evidence from satellite imagery indicates the Puncak Jaya glaciers have been retreating rapidly. The Meren Glacier melted away sometime between 1994 and 2000.[14]

An expedition led by paleoclimatologist Lonnie Thompson in 2010 found that the glaciers are disappearing at a rate of seven metres (23 ft) thickness per year and in 2018 they were predicted to vanish in the 2020s.[15][16]

Climbing

.jpg)

Puncak Jaya is one of the more demanding climbs in one version of the Seven Summits, despite having the lowest elevation. It is held to have the highest technical rating, though not the greatest physical demands of that list's ascents.

The standard route to climb the peak from its base camp is up the north face and along the summit ridge, which is all hard rock surface.[17] Despite the large mine, the area is highly inaccessible to hikers and the general public. The standard route to access base camp as of 2013 is to fly into the nearest major town with an airport, Timika, and then take a small aircraft over the mountain range and onto an unimproved runway at one of the local villages far down from the peak. It is then typically a five-day hike via the Jungle route to the base camp through very dense jungle and with regular rainfall, making the approach probably the "most miserable" of the Seven Summits. Rain during most days of the hike inbound and out are not uncommon. Unlike the other Seven Summits, if one sustains an injury on the inbound hike, there is little or no ability to get rescued via helicopter. Anyone injured must evacuate by foot over very difficult and slippery terrain.

The descent from the peak's base camp can take three to four days. Anecdotally, it appears most injuries occur during the descent due to a combination of exhaustion and difficulty controlling hiking speed on the wet and slippery terrain.

An additional complication is relatively common work strikes by the climbing porters that accompany most expeditions, occasionally halting their work to demand (and usually receive) higher pay before agreeing to continue. The one-day summit bid is technically challenging for those with little rock climbing experience, and it can be quite cold with temperatures at or below freezing near the summit. Patches of snow sometimes appear on the route up or on the ropes of the Tyrolean traverse just below the summit.

See also

References

- The elevation given here was determined by the 1971–73 Australian Universities' Expedition and is supported by the Seven Summits authorities and modern high resolution radar data. An older but still often quoted elevation of 5,030 metres (16,503 ft) is obsolete.

- Greater Atlas of the World, Mladinska knjiga, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1986.

- Statistical Yearbook of Croatia, 2007

- Neill, Wilfred T. (1973). Twentieth-Century Indonesia. Columbia University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-231-08316-4.

- Lorentz, H.A., 1910. Zwarte Menschen – Witte Bergen: Verhaal van den Tocht naar het Sneeuwgebergte van Nieuw-Guinea, Leiden: EJ. Brill.

- Interview with Jean Jacques Dozy in 2002 (in Dutch).

- Philip Temple Account of first ascent

- Parfet, Bo; Buskin, Richard (2009). Die Trying: One Man's Quest to Conquer the Seven Summits. New York, N.Y.: American Management Association. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8144-1084-4.

- Dow, D.B.; Sukamto R. (1984). "Late Tertiary to Quaternary Tectonics of Irian Jaya" (PDF). Episodes. 7 (4): 3–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Weiland, Richard J.; Cloos, Mark (1996). "Pliocene-Pleistocene asymmetric unroofing of the Irian fold belt, Irian Jaya, Indonesia: Apatite fission-track thermochronology". GSA Bulletin. 108 (11): 1438–49. Bibcode:1996GSAB..108.1438W. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1996)108<1438:ppauot>2.3.co;2.

- "Seven Summits Page". 7summits.com. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Kincaid, Joni L.; Klein, Andrew G (2004). "Retreat of the Irian Jaya Glaciers from 2000 to 2002" (pdf). 61st Eastern Snow Conference. pp. 147–157. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- Ian Allison and James A. Peterson. "Glaciers of Irian Jaya, Indonesia and New Zealand". U.S. Geological Survey, U.S.Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- Joni L. Kincaid and Andrew G. Klein. "Retreat of the Irian Jaya Glaciers from 2000 to 2002 as Measured from IKONOS Satellite Images" (pdf). 61st Eastern Snow Conference Portland, Maine, USA 2004. Retrieved 2004. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Papua Glacier's Secrets Dripping Away: Scientists". Jakarta Globe. Agence France-Presse. July 2, 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Wang, Shan-shan; Veettil, Bijeesh Kozhikkodan (2018-03-01). "State and fate of the remaining tropical mountain glaciers in australasia using satellite imagery". Journal of Mountain Science. 15 (3): 495–503. doi:10.1007/s11629-017-4539-0. ISSN 1993-0321.

- Jones, Lola (15 December 2009). "The most technical of the 7 summits". Xtreme Sport.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puncak Jaya. |