Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is a sovereign state consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania lying to the east of Papua New Guinea and northwest of Vanuatu and covering a land area of 28,400 square kilometres (11,000 sq mi). The country has a population of 652,858 [8] and its capital, Honiara, is located on the island of Guadalcanal. The country takes its name from the Solomon Islands archipelago, which is a collection of Melanesian islands that also includes the North Solomon Islands (a part of Papua New Guinea), but excludes outlying islands, such as Rennell and Bellona, and the Santa Cruz Islands.

Solomon Islands | |

|---|---|

Motto: "To Lead is to Serve" | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Honiara 9°28′S 159°49′E |

| Official languages | English |

| Ethnic groups (2009 Census) |

|

| Religion (2016)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Solomon Islander |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| David Vunagi | |

| Manasseh Sogavare | |

| Legislature | National Parliament |

| Independence | |

• from the United Kingdom | 7 July 1978 |

| Area | |

• Total | 28,400 km2 (11,000 sq mi) (139th) |

• Water (%) | 3.2% |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 652,857[4][5] (167th) |

• Density | 18.1/km2 (46.9/sq mi) (200th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $1.479 billion[6] |

• Per capita | $2,307[6] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $1.511 billion[6] |

• Per capita | $2,357[6] |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 153rd |

| Currency | Solomon Islands dollar (SBD) |

| Time zone | UTC+11 |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +677 |

| ISO 3166 code | SB |

| Internet TLD | .sb |

In 1568, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña was the first European to visit them, naming them the Islas Salomón.[9] Britain defined its area of interest in the Solomon Islands archipelago in June 1893, when Captain Gibson R.N., of HMS Curacoa, declared the southern Solomon Islands a British protectorate.[10][11] During World War II, the Solomon Islands campaign (1942–1945) saw fierce fighting between the United States, Commonwealth forces and the Empire of Japan, such as in the Battle of Guadalcanal.

The official name of the then British administration was changed from the British Solomon Islands Protectorate to the Solomon Islands in 1975, and self-government was achieved the following year. Independence was obtained, and the name changed to just "Solomon Islands" (without the definite article), in 1978. At independence, Solomon Islands became a constitutional monarchy. The Queen of Solomon Islands is Elizabeth II, represented by the Governor-General.

Name

In 1568, the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña was the first European to visit the Solomon Islands archipelago, naming it Islas Salomón ("Solomon Islands") after the wealthy biblical King Solomon.[9] It is said that they were given this name in the mistaken assumption that they contained great riches,[12] and he believed them to be the Bible-mentioned city of Ophir.[13] During most of the colonial period the territory’s official name was “British Solomon Islands Protectorate” until 1975 when it was changed to “Solomon Islands”.[14][15] The definite article, "the", is not part of the country's official name but is sometimes used, both within and outside the country. Colloquially, and during the Solomon Islands campaign, the islands are (were) referred to simply as "the Solomons".[16]

History

Early history

It is believed that Papuan-speaking settlers began to arrive around 30,000 BC.[17] Austronesian speakers arrived c. 4000 BC also bringing cultural elements such as the outrigger canoe. Between 1200 and 800 BC the ancestors of the Polynesians, the Lapita people, arrived from the Bismarck Archipelago with their characteristic ceramics.[18]

European contact (1568)

The first European to visit the islands was the Spanish navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, coming from Peru in 1568.

Some of the earliest and most regular foreign visitors to the islands were whaling vessels from Britain, the United States and Australia.[19] They came for food, wood and water from late in the 18th century and, later, took aboard islanders to serve as crewmen on their ships.[20] Relations between the islanders and visiting seamen was not always good and sometimes there was violence and bloodshed.[21]

Missionaries began visiting the Solomons in the mid-19th century. They made little progress at first, because "blackbirding" (the often brutal recruitment or kidnapping of labourers for the sugar plantations in Queensland and Fiji) led to a series of reprisals and massacres. The evils of the slave trade prompted the United Kingdom to declare a protectorate over the southern Solomons in June 1893.[22]

In 1898 and 1899, more outlying islands were added to the protectorate; in 1900 the remainder of the archipelago, an area previously under German jurisdiction, was transferred to British administration, apart from the islands of Buka and Bougainville, which remained under German administration as part of German New Guinea. Traditional trade and social intercourse between the western Solomon Islands of Mono and Alu (the Shortlands) and the traditional societies in the south of Bougainville, however, continued without hindrance.

Missionaries settled in the Solomons under the protectorate, converting most of the population to Christianity. In the early 20th century several British and Australian firms began large-scale coconut planting. Economic growth was slow, however, and the islanders benefited little.

Journalist Joe Melvin visited in 1892, as part of his undercover investigation into blackbirding. In 1908 the islands were visited by Jack London, who was cruising the Pacific on his boat, the Snark.

Second World War and post-war era

From 1942 until the end of 1943, the Solomon Islands were the scene of several major land, sea and air battles between the Allies and the Japanese Empire's armed forces. Tens of thousands of Allied and Japanese combatants as well as local civilians lost their lives as a result of the conflict. The Guadalcanal (1942-1943) and New Georgia campaigns (1943) were turning points in the Pacific War, stopping and then countering the Japanese advance. The Islands became one of the major staging areas in the South Pacific.

Coastwatchers from the Solomon Islands played a major role in providing intelligence and rescuing other Allied servicemen. U.S. Admiral William Halsey, the commander of Allied forces during the Battle for Guadalcanal, recognized the coastwatchers' contributions by stating "The coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific."[23]

Around 3,200 men served in the Solomon Islands Labour Corps during the war and their exposure to Americans led to several social and political transformations. The Pijin language was heavily influenced by the communication between Americans and the Islands inhabitants. Ideas about self-determination and class consciousness took hold and several former members of the Labour Corps formed the anti-colonial Maasina Rule movement after the war. Massina Rule would go on to play a major role during the post-war period when political unrest in Malaita and elsewhere led to the colonial government's 1952 reforms in which local government councils, regular elections and universal adult suffrage were all established.[24]

_under_attack_and_burning_during_the_Battle_of_the_Eastern_Solomons_on_24_August_1942_(NH_97778).jpg) The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) under aerial attack during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons

The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV-6) under aerial attack during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons American Marines rest during the 1942 Guadalcanal Campaign.

American Marines rest during the 1942 Guadalcanal Campaign.- American forces landing at Rendova Island

The Cactus Air Force at Henderson Field, Guadalcanal in October 1942.

The Cactus Air Force at Henderson Field, Guadalcanal in October 1942. The coastwatcher Jacob C. Vouza on Guadalcanal.

The coastwatcher Jacob C. Vouza on Guadalcanal.

Independence (1978)

In addition to the 1952 establishment of local councils, a new constitution was established in 1970 and elections were held, although the constitution was contested and a new one was created in 1974. In 1973 the first oil price shock occurred, and the increased cost of running a colony became apparent to British administrators.

Following the independence of neighbouring Papua New Guinea from Australia in 1975, the Solomon Islands gained self-government in 1976. Under the terms of the Solomon Islands Act 1978 the country was annexed to Her Majesty’s dominions and granted independence on 7 July 1978. The first Prime Minister was Sir Peter Kenilorea. Queen Elizabeth II became Queen of Solomon Islands.

The Solomon Islands Independence Ceremony on 7 July 1978

The Solomon Islands Independence Ceremony on 7 July 1978 The Five Dollar Proof Coin

The Five Dollar Proof Coin The Five Dollar Proof Coin of the Solomon Islands 24 October 1977

The Five Dollar Proof Coin of the Solomon Islands 24 October 1977

Ethnic violence (1998–2003)

Commonly referred to as the tensions or the ethnic tension, the initial civil unrest was mainly characterised by fighting between the Isatabu Freedom Movement (also known as the Guadalcanal Revolutionary Army) and the Malaita Eagle Force (as well as the Marau Eagle Force). (Although much of the conflict was between Guales and Malaitans, Kabutaulaka (2001)[25] and Dinnen (2002) argue that the 'ethnic conflict' label is an oversimplification.)

In late 1998, militants on the island of Guadalcanal began a campaign of intimidation and violence towards Malaitan settlers. During the next year, thousands of Malaitans fled back to Malaita or to the capital, Honiara (which, although situated on Guadalcanal, is predominantly populated by Malaitans and Solomon Islanders from other provinces). In 1999, the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF) was established in response.

The reformist government of Bartholomew Ulufa'alu struggled to respond to the complexities of this evolving conflict. In late 1999, the government declared a four-month state of emergency. There were also a number of attempts at reconciliation but to no avail. Ulufa'alu also requested assistance from Australia and New Zealand in 1999 but his appeal was rejected.

In the June 2000 coup d'état, Ulufa'alu was kidnapped by militia members of the MEF who felt that, although he was a Malaitan, he was not doing enough to protect their interests. Ulufa'alu subsequently resigned in exchange for his release. Manasseh Sogavare, who had earlier been Finance Minister in Ulufa'alu's government but had subsequently joined the opposition, was elected as Prime Minister by 23–21 over the Rev. Leslie Boseto. However, Sogavare's election was immediately shrouded in controversy because six MPs (thought to be supporters of Boseto) were unable to attend parliament for the crucial vote (Moore 2004, n.5 on p. 174).

In October 2000, the Townsville Peace Agreement[26] was signed by the Malaita Eagle Force, elements of the IFM, and the Solomon Islands Government. This was closely followed by the Marau Peace agreement in February 2001, signed by the Marau Eagle Force, the Isatabu Freedom Movement, the Guadalcanal Provincial Government, and the Solomon Islands Government. However, a key Guale militant leader, Harold Keke, refused to sign the agreement, causing a split with the Guale groups. Subsequently, Guale signatories to the agreement led by Andrew Te'e joined with the Malaitan-dominated police to form the 'Joint Operations Force'. During the next two years the conflict moved to the Weathercoast of Guadalcanal as the Joint Operations unsuccessfully attempted to capture Keke and his group.

New elections in December 2001 brought Allan Kemakeza into the Prime Minister's chair with the support of his People's Alliance Party and the Association of Independent Members. Law and order deteriorated as the nature of the conflict shifted: there was continuing violence on the Weathercoast while militants in Honiara increasingly turned their attention to crime and extortion. The Department of Finance would often be surrounded by armed men when funding was due to arrive. In December 2002, Finance Minister Laurie Chan resigned after being forced at gunpoint to sign a cheque made out to some of the militants. Conflict also broke out in Western Province between locals and Malaitan settlers. Renegade members of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) were invited in as a protection force but ended up causing as much trouble as they prevented.

The prevailing atmosphere of lawlessness, widespread extortion, and ineffective police prompted a formal request by the Solomon Islands Government for outside help. With the country bankrupt and the capital in chaos, the request was unanimously supported in Parliament.

In July 2003, Australian and Pacific Island police and troops arrived in Solomon Islands under the auspices of the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). A sizeable international security contingent of 2,200 police and troops, led by Australia and New Zealand, and with representatives from about 20 other Pacific nations, began arriving the next month under Operation Helpem Fren. Since this time some commentators have considered the country a failed state.[27] However, other academics argue that rather than being a 'failed state', it is an unformed state: a state that never consolidated even after decades of independence.[28]

In April 2006, allegations that the newly elected Prime Minister Snyder Rini had used bribes from Chinese businessmen to buy the votes of members of Parliament led to mass rioting in the capital Honiara. A deep underlying resentment against the minority Chinese business community led to much of Chinatown in the city being destroyed.[29] Tensions were also increased by the belief that large sums of money were being exported to China. China sent chartered aircraft to evacuate hundreds of Chinese who fled to avoid the riots. Evacuation of Australian and British citizens was on a much smaller scale. Additional Australian, New Zealand and Fijian police and troops were dispatched to try to quell the unrest. Rini eventually resigned before facing a motion of no-confidence in Parliament, and Parliament elected Manasseh Sogavare as Prime Minister.

Earthquakes

On 2 April 2007 at 07:39:56 local time (UTC+11) an earthquake with magnitude 8.1 occurred at hypocenter S8.453 E156.957, 349 kilometres (217 miles) northwest of the island's capital, Honiara and south-east of the capital of Western Province, Gizo, at a depth of 10 km (6.2 miles).[30] More than 44 aftershocks with magnitude 5.0 or greater occurred up until 22:00:00 UTC, Wednesday, 4 April 2007. A tsunami followed killing at least 52 people, destroying more than 900 homes and leaving thousands of people homeless.[31] Land upthrust extended the shoreline of one island, Ranongga, by up to 70 metres (230 ft) exposing many once pristine coral reefs.[32]

On 6 February 2013, an earthquake with magnitude of 8.0 occurred at epicentre S10.80 E165.11 in the Santa Cruz Islands followed by a tsunami up to 1.5 metres. At least nine people were killed and many houses demolished. The main quake was preceded by a sequence of earthquakes with a magnitude of up to 6.0.

Politics

.jpg)

Solomon Islands is a constitutional monarchy and has a parliamentary system of government. As Queen of Solomon Islands, Elizabeth II is head of state; she is represented by the Governor-General who is chosen by the Parliament for a five-year term. There is a unicameral parliament of 50 members, elected for four-year terms. However, Parliament may be dissolved by majority vote of its members before the completion of its term.

Parliamentary representation is based on single-member constituencies. Suffrage is universal for citizens over age 21.[33] The head of government is the Prime Minister, who is elected by Parliament and chooses the cabinet. Each ministry is headed by a cabinet member, who is assisted by a permanent secretary, a career public servant who directs the staff of the ministry.

Solomon Islands governments are characterised by weak political parties (see List of political parties in Solomon Islands) and highly unstable parliamentary coalitions. They are subject to frequent votes of no confidence, leading to frequent changes in government leadership and cabinet appointments.

Land ownership is reserved for Solomon Islanders. The law provides that resident expatriates, such as the Chinese and Kiribati, may obtain citizenship through naturalisation. Land generally is still held on a family or village basis and may be handed down from mother or father according to local custom. The islanders are reluctant to provide land for nontraditional economic undertakings, and this has resulted in continual disputes over land ownership.

No military forces are maintained by Solomon Islands although a police force of nearly 500 includes a border protection unit. The police also are responsible for fire service, disaster relief, and maritime surveillance. The police force is headed by a commissioner, appointed by the governor-general and responsible to the prime minister. On 27 December 2006, the Solomon Islands Government took steps to prevent the country's Australian police chief from returning to the Pacific nation. On 12 January 2007, Australia replaced its top diplomat expelled from Solomon Islands for political interference in a conciliatory move aimed at easing a four-month dispute between the two countries.

On 13 December 2007, Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare was toppled by a vote of no confidence in Parliament,[34] following the defection of five ministers to the opposition. It was the first time a prime minister had lost office in this way in Solomon Islands. On 20 December, Parliament elected the opposition's candidate (and former Minister for Education) Derek Sikua as Prime Minister, in a vote of 32 to 15.[35][36]

Judiciary

The Governor General appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. The Governor General appoints the other justices with the advice of a judicial commission. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (based in the United Kingdom) serves as the highest appellate court. The current Chief Justice is Sir Albert Palmer.

Since March 2014 Justice Edwin Goldsbrough has served as the President of the Court of Appeal for Solomon Islands. Justice Goldsbrough has previously served a five-year term as a Judge of the High Court of Solomon Islands (2006–2011). Justice Edwin Goldsbrough then served as the Chief Justice of the Turks and Caicos Islands.[37]

Foreign relations

Solomon Islands is a member of the United Nations, Interpol, Commonwealth, Pacific Islands Forum, Pacific Community, International Monetary Fund, and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries (ACP) (Lomé Convention).

Until September 2019, it was one of the few countries to recognise the Republic of China (Taiwan) and maintain formal diplomatic relations with the latter.[38] Relations with Papua New Guinea, which had become strained because of an influx of refugees from the Bougainville rebellion and attacks on the northern islands of Solomon Islands by elements pursuing Bougainvillean rebels, have been repaired. A 1998 peace accord on Bougainville removed the armed threat, and the two nations regularised border operations in a 2004 agreement.

In March 2017, at the 34th regular session of the UN Human Rights Council, Vanuatu made a joint statement on behalf of Solomon Islands and some other Pacific nations raising human rights violations in the Western New Guinea, which has been occupied by Indonesia since 1963,[39] and requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights produce a report.[40][41] Indonesia rejected Vanuatu's allegations.[41] More than 100,000 Papuans have died during a 50-year Papua conflict.[42] In September 2017, at the 72nd Session of the UN General Assembly, the Prime Ministers of the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu once again raised human rights abuses in Indonesian-occupied West Papua.[43]

Military

Although the locally recruited British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force was part of Allied Forces taking part in fighting in the Solomons during the Second World War, the country has not had any regular military forces since independence. The various paramilitary elements of the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF) were disbanded and disarmed in 2003 following the intervention of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). RAMSI has a small military detachment headed by an Australian commander with responsibilities for assisting the police element of RAMSI in internal and external security. The RSIPF still operates two Pacific class patrol boats (RSIPV Auki and RSIPV Lata), which constitute the de facto navy of Solomon Islands.

In the long term, it is anticipated that the RSIPF will resume the defence role of the country. The police force is headed by a commissioner, appointed by the governor general and responsible to the Minister of Police, National Security & Correctional Services.

The police budget of Solomon Islands has been strained due to a four-year civil war. Following Cyclone Zoe's strike on the islands of Tikopia and Anuta in December 2002, Australia had to provide the Solomon Islands government with 200,000 Solomon dollars ($50,000 Australian) for fuel and supplies for the patrol boat Lata to sail with relief supplies. (Part of the work of RAMSI includes assisting the Solomon Islands government to stabilise its budget.)

Administrative divisions

For local government, the country is divided into ten administrative areas, of which nine are provinces administered by elected provincial assemblies and the tenth is the capital Honiara, administered by the Honiara Town Council.

| # | Province | Capital | Premier | Area (km²) | Population census 1999 | Population per km² (2009) | Population census 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tulagi | Patrick Vasuni | 615 | 21,577 | 42.4 | 26,051 | |

| 2 | Taro Island | Jackson Kiloe | 3,837 | 20,008 | 6.9 | 26,371 | |

| 3 | Honiara | Anthony Veke | 5,336 | 60,275 | 17.5 | 93,613 | |

| 4 | Buala | James Habu | 4,136 | 20,421 | 6.3 | 26,158 | |

| 5 | Kirakira | Stanley Siapu | 3,188 | 31,006 | 12.7 | 40,419 | |

| 6 | Auki | Peter Ramohia | 4,225 | 122,620 | 32.6 | 137,596 | |

| 7 | Tigoa | George Tuhaika | 671 | 2,377 | 4.5 | 3,041 | |

| 8 | Lata | Fr. Charles Brown Beu | 895 | 18,912 | 23.9 | 21,362 | |

| 9 | Gizo | David Gina | 5,475 | 62,739 | 14.0 | 76,649 | |

| – | Honiara | Mua (Mayor) | 22 | 49,107 | 2,936.8 | 64,609 | |

| Solomon Islands | Honiara | – | 28,400 | 409,042 | 14.7 | 515,870 |

[1] excluding the Capital Territory of Honiara

Human rights

There are human rights concerns and issues in regards to education, water, sanitation, gender equality, and domestic violence.

Homosexuality is illegal in Solomon Islands.[44]

Geography

.jpg)

Solomon Islands is an island nation that lies east of Papua New Guinea and consists of many islands: Choiseul, the Shortland Islands; the New Georgia Islands; Santa Isabel; the Russell Islands; Nggela (the Florida Islands); Malaita; Guadalcanal; Sikaiana; Maramasike; Ulawa; Uki; Makira (San Cristobal); Santa Ana; Rennell and Bellona; the Santa Cruz Islands and the remote, tiny outliers, Tikopia, Anuta, and Fatutaka.

The country's islands lie between latitudes 5° and 13°S, and longitudes 155° and 169°E. The distance between the westernmost and easternmost islands is about 1,500 kilometres (930 mi). The Santa Cruz Islands (of which Tikopia is part) are situated north of Vanuatu and are especially isolated at more than 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the other islands. Bougainville is geographically part of the Solomon Islands archipelago but politically part of Papua New Guinea.

Climate

The islands' ocean-equatorial climate is extremely humid throughout the year, with a mean temperature of 26.5 °C (79.7 °F) and few extremes of temperature or weather. June through August is the cooler period. Though seasons are not pronounced, the northwesterly winds of November through April bring more frequent rainfall and occasional squalls or cyclones. The annual rainfall is about 3,050 millimetres (120 in).

Ecology

The Solomon Islands archipelago is part of two distinct terrestrial ecoregions. Most of the islands are part of the Solomon Islands rain forests ecoregion, which also includes the islands of Bougainville and Buka; these forests have come under pressure from forestry activities. The Santa Cruz Islands are part of the Vanuatu rain forests ecoregion, together with the neighbouring archipelago of Vanuatu. Soil quality ranges from extremely rich volcanic (there are volcanoes with varying degrees of activity on some of the larger islands) to relatively infertile limestone. More than 230 varieties of orchids and other tropical flowers brighten the landscape. Mammals are scarce on the islands, with the only terrestrial mammals being bats and small rodents. Birds and reptiles, however, are abundant.

The islands contain several active and dormant volcanoes. The Tinakula and Kavachi volcanoes are the most active.

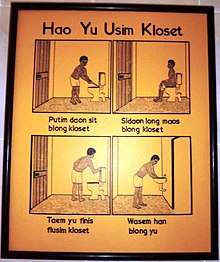

Water and sanitation

See also: Human rights in Solomon Islands

Scarcity of fresh water sources and lack of sanitation has been a constant challenge facing Solomon Islands. Reducing the number of those living without access to fresh water and sanitation by half was one of the 2015 Millennium Development Goals (MDG's) implemented by the United Nations through Goal 7, to ensure environmental sustainability.[45] Though the islands generally have access to fresh water sources, it is typically only available in the state's capital of Honiara,[45] and it is not guaranteed all year long. According to a UNICEF report, even the capital's poorest communities do not have access to adequate places to relieve their waste, and an estimated 70% Solomon Island schools have no access to safe and clean water for drinking, washing and relieving of waste.[45] Lack of safe drinking water in school-age children results in high risks of contracting fatal diseases such as cholera and typhoid.[46] The number of Solomon Islanders living with piped drinking water has been decreasing since 2011, while those living with non-piped water increased between 2000 and 2010. Nevertheless, one improvement is that those living with non-piped water has been decreasing consistently since 2011.[47]

In addition, the Solomon Islands Second Rural Development Program, enacted in 2014 and active until 2020, has been working to deliver competent infrastructure and other vital services to rural areas and villages of the Solomon Islands,[48] which suffer the most from lack of safe drinking water and proper sanitation. Through improved infrastructure, services and resources, the program has also encouraged farmers and other agricultural sectors, through community-driven efforts, to connect them to the market, thus promoting economic growth.[46] Rural villages such as Bolava, found in the Western Province of Solomon Islands, have benefited greatly from the program, with the implementation of water tanks and rain catchment and water storage systems.[46] Not only has the improved infrastructure increased the quality of life in Solomon Islands, the services are also operated and developed by the community, thus creating a sense of communal pride and achievement among those previously living in hazardous conditions. The program is funded by various international development actors such as the World Bank, European Union, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the Australian and Solomon Islands governments.[46]

Economy

Solomon Islands' per-capita GDP of $600 ranks it as a lesser developed nation, and more than 75% of its labour force is engaged in subsistence agriculture and fishing. Most manufactured goods and petroleum products must be imported. Only 3.9% of the area of the islands are used for agriculture, and 78.1% are covered by forests making the Solomon Islands the 103th ranked country covered by forests worldwide.[49]

Export

Until 1998, when world prices for tropical timber fell steeply, timber was Solomon Islands' main export product, and, in recent years, Solomon Islands forests were dangerously overexploited. In the wake of the ethnic violence in June 2000, exports of palm oil and gold ceased while exports of timber fell. Recently, Solomon Islands courts have re-approved the export of live dolphins for profit, most recently to Dubai, United Arab Emirates. This practice was originally stopped by the government in 2004 after international uproar over a shipment of 28 live dolphins to Mexico. The move resulted in criticism from both Australia and New Zealand as well as several conservation organisations.

Agriculture

Other important cash crops and exports include copra, cacao and palm oil. In 2017 317,682 tons of coconuts were harvested making the country the 18th ranked producer of coconuts worldwide, and 24% of the exports corresponded to copra.[50] Cocoa beans are mainly grown on the islands Guadalcanal, Makira and Malaita. In 2017 4,940 tons of cocoa beans were harvested making the Solomon Islands the 27th ranked producer of cocoa worldwide.[51] Growth of production and export of copra and cacao, however, is hampered by old age of most coconut and cacao trees. In 2017 285,721 tons of palm oil were produced,making Solomon Islands the 24th ranked producer of palm oil worldwide.[52] The agriculture on the Solomon Islands is hampered by a very severe lack of agricultural machines. For the local market but not for export many families grow taro (2017: 45,901 tons),[53] rice (2017: 2,789 tons),[54] yams (2017: 44,940 tons)[55] and bananas (2017: 313 tons).[56] Tobacco (2017: 118 tons)[57] and spices (2017: 217 tons).[58] are grown for the local market as well.

Mining

In 1998 gold mining began at Gold Ridge on Guadalcanal. Minerals exploration in other areas continued.The islands are rich in undeveloped mineral resources such as lead, zinc, nickel, and gold. Negotiations are underway that may lead to the eventual reopening of the Gold Ridge mine which was closed after the riots in 2006.

Fisheries

Solomon Islands' fisheries also offer prospects for export and domestic economic expansion. A Japanese joint venture, Solomon Taiyo Ltd., which operated the only fish cannery in the country, closed in mid-2000 as a result of the ethnic disturbances. Though the plant has reopened under local management, the export of tuna has not resumed.

Tourism

Tourism, particularly diving, could become an important service industry for Solomon Islands. Tourism growth, however, is hampered by lack of infrastructure and transportation limitations. In 2017 the Solomon Islands were visited by 26,000 tourists making the country one of the least frequently-visited countries of the world.[59] The Government hopes to increase the number of tourists up to 30,000 by the end of 2019 and up to 60,000 tourists per year by the end of 2025.[60]

Currency

The Solomon Islands dollar (ISO 4217 code: SBD) was introduced in 1977, replacing the Australian dollar at par. Its symbol is "SI$", but the "SI" prefix may be omitted if there is no confusion with other currencies also using the dollar sign "$". It is subdivided into 100 cents. Local shell money is still important for traditional and ceremonial purposes in certain provinces and, in some remote parts of the country, for trade. Shell money was a widely used traditional currency in the Pacific Islands, in Solomon Islands, it is mostly manufactured in Malaita and Guadalcanal but can be bought elsewhere, such as the Honiara Central Market.[61] The barter system often replaces money of any kind in remote areas. The Solomon Islands Government was insolvent by 2002. Since the RAMSI intervention in 2003, the government has recast its budget. It has consolidated and renegotiated its domestic debt and with Australian backing, is now seeking to renegotiate its foreign obligations. Principal aid donors are Australia, New Zealand, the European Union, Japan and Taiwan.

Energy

A team of renewable energy developers working for the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC) and funded by the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP), have developed a scheme that allows local communities to access renewable energy, such as solar, water and wind power, without the need to raise substantial sums of cash. Under the scheme, islanders who are unable to pay for solar lanterns in cash may pay instead in kind with crops.[62]

Infrastructure

Flight connections

Solomon Airlines connects Honiara to Nadi in Fiji, Port Vila in Vanuatu and Brisbane in Australia as well as to more than 20 domestic airports in each province of the country. To promote tourism Solomon Airlines introduced a weekly direct flight connection between Brisbane and Munda in 2019.[63] Virgin Australia connects Honiara to Brisbane twice a week. Most of the domestic airports are accessible to small planes only as they have short, grass runways.

Roads

The road system in Solomon Islands is insufficient and there are no railways. The most important roads connect Honiara to Lambi (58 km) in the western part of Guadalcanal and to Aola (75 km) in the eastern part.[64] There are few buses and these do not circulate according to a fixed timetable. In Honiara there is no bus terminus. The most important bus stop is in front of the Central Market.

Ferries

Most of the islands can be reached by ferry from Honiara. There is a daily connection from Honiara to Auki via Tulagi by a high speed catamaran.

Demographics

| Population[4][5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 0.09 | ||

| 2000 | 0.4 | ||

| 2018 | 0.7 | ||

As of 2018, there were 652,857 people in Solomon Islands.[4][5]

Ethnic groups

.jpg)

The majority of Solomon Islanders are ethnically Melanesian (95.3%). Polynesian (3.1%) and Micronesian (1.2%) are the two other significant groups.[65] There are a few thousand ethnic Chinese.[29]

Languages

While English is the official language, only 1–2% of the population are able to communicate fluently in English. However, an English creole, Solomons Pijin, is a de facto lingua franca of the country spoken by the majority of the population, along with local tribal languages. Pijin is closely related to Tok Pisin spoken in Papua New Guinea.

The number of local languages listed for Solomon Islands is 74, of which 70 are living languages and 4 are extinct, according to Ethnologue, Languages of the World.[66] Western Oceanic languages (predominantly of the Southeast Solomonic group) are spoken on the central islands. Polynesian languages are spoken on Rennell and Bellona to the south, Tikopia, Anuta and Fatutaka to the far east, Sikaiana to the north east, and Luaniua to the north (Ontong Java Atoll, also known as Lord Howe Atoll). The immigrant population of Gilbertese (I-Kiribati) speaks an Oceanic language.

Religion

The religion of Solomon Islands is mainly Christian (comprising about 92% of the population). The main Christian denominations are: the Anglican Church of Melanesia (35%), Roman Catholic (19%), South Seas Evangelical Church (17%), United Church in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands (11%) and Seventh-day Adventist (10%). Other Christian denominations are Jehovah's Witnesses, New Apostolic Church (80 churches) and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).

Another 5% adhere to aboriginal beliefs. The remaining adhere to Islam, the Baha'i Faith. According to the most recent reports, Islam in Solomon Islands is made up of approximately 350 Muslims,[67] including members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.[68]

Health

Female life expectancy at birth was at 66.7 years and male life expectancy at birth at 64.9 in 2007.[69] 1990–1995 fertility rate was at 5.5 births per woman.[69] Government expenditure on health per capita was at US$99 (PPP).[69] Healthy life expectancy at birth is at 60 years.[69]

Blond hair occurs in 10% of the population in the islands.[70] After years of questions, studies have resulted in the better understanding of the blond gene. The findings show that the blond hair trait is due to an amino acid change of protein TYRP1.[71] This accounts for the highest occurrence of blond hair outside of European influence in the world.[72] While 10% of Solomon Islanders display the blond phenotype, about 26% of the population carry the recessive trait for it as well.[73]

Education

Education in Solomon Islands is not compulsory, and only 60 percent of school-age children have access to primary education.[74][75] There are kindergartens in various places, e.g. in the capital, but they are not free.

From 1990 to 1994, the gross primary school enrolment rose from 84.5 percent to 96.6 percent.[74] Primary school attendance rates were unavailable for Solomon Islands as of 2001.[74] While enrolment rates indicate a level of commitment to education, they do not always reflect children's participation in school.[74] The Department of Education and Human Resource Development efforts and plans to expand educational facilities and increase enrolment. However, these actions have been hindered by a lack of government funding, misguided teacher training programs, poor co-ordination of programs, and a failure of the government to pay teachers.[74] The percentage of the government's budget allocated to education was 9.7 percent in 1998, down from 13.2 percent in 1990.[74] Male educational attainment tends to be higher than female educational attainment.[75] The University of the South Pacific has a Campus at Guadalcanal as a foothold in the country while this University has established by Papua New Guinea.[76] The literacy rate of the adult population amounted to 84.1% in 2015 (men 88,9%, women 79,23%).[77]

Culture

The culture of Solomon Islands reflects the extent of the differentiation and diversity among the groups living within the Solomon Islands archipelago, which lies within Melanesia in the Pacific Ocean, with the peoples distinguished by island, language, topography, and geography. The cultural area includes the nation state of Solomon Islands and the Bougainville Island, which is a part of Papua New Guinea.[78] Solomon Islands includes some culturally Polynesian societies which lie outside the main region of Polynesian influence, known as the Polynesian Triangle. There are seven Polynesian outliers within the Solomon Islands: Anuta, Bellona, Ontong Java, Rennell, Sikaiana, Tikopia, and Vaeakau-Taumako. Solomon Islands arts and crafts cover a wide range of woven objects, carved wood, stone and shell artefacts in styles specific to different provinces. :

Laundry Basket

Laundry Basket Carved fish

Carved fish Bukhaware trays

Bukhaware trays Carved dish inlaid with mother-of-pearl

Carved dish inlaid with mother-of-pearl Carved Longboat

Carved Longboat Gnusu Gnusu Heads

Gnusu Gnusu Heads Salad Bowl and serving spoon and fork

Salad Bowl and serving spoon and fork Wooden religious objects in front of All Saints' Church, Honiara

Wooden religious objects in front of All Saints' Church, Honiara

Gender inequality and domestic violence

Solomon Islands has one of the highest rates of family and sexual violence (FSV) in the world, with 64% of women aged 15–49 having reported physical and/or sexual abuse by a partner.[79] As per a World Health Organization (WHO) report issued in 2011, "the causes of Gender Based Violence (GBV) are multiple, but it primarily stems from gender inequality and its manifestations."[80] The report stated:

- "In Solomon Islands, GBV has been largely normalized: 73% of men and 73% of women believe violence against women is justifiable, especially for infidelity and 'disobedience,' as when women do 'not live up to the gender roles that society imposes.' For example, women who believed they could occasionally refuse sex were four times more likely to experience GBV from an intimate partner. Men cited acceptability of violence and gender inequality as two main reasons for GBV, and almost all of them reported hitting their female partners as a 'form of discipline,' suggesting that women could improve the situation by '[learning] to obey [them].'"

Another manifestation and driver of gender inequality in Solomon Islands is the traditional practice of bride price. Although specific customs vary between communities, paying a bride price is considered similar to a property title, giving men ownership over women. Gender norms of masculinity tend to encourage men to "control" their wives, often through violence, while women felt that bride prices prevented them from leaving men. Another report issued by the WHO in 2013 painted a similarly grim picture.[81]

In 2014, Solomon Islands officially launched the Family Protection Act 2014, which was aimed at curbing domestic violence in the country.[82] While numerous other interventions are being developed and implemented in the healthcare system as well as the criminal justice system, these interventions are still in their infancy and have largely stemmed from Western protocols. Therefore, for these models to be effective, time and commitment is needed to change the cultural perception of domestic violence in Solomon Islands.[79]

Literature

Writers from Solomon Islands include the novelists Rexford Orotaloa and John Saunana and the poet Jully Makini.

Media

- Newspapers

There is one daily newspaper, the Solomon Star, one daily online news website, Solomon Times Online (www.solomontimes.com), two weekly papers, Solomons Voice and Solomon Times, and two monthly papers, Agrikalsa Nius and the Citizen's Press.

- Radio

Radio is the most influential type of media in Solomon Islands due to language differences, illiteracy,[83] and the difficulty of receiving television signals in some parts of the country. The Solomon Islands Broadcasting Corporation (SIBC) operates public radio services, including the national stations Radio Happy Isles 1037 on the dial and Wantok FM 96.3, and the provincial stations Radio Happy Lagoon and, formerly, Radio Temotu. There are two commercial FM stations, Z FM at 99.5 in Honiara but receivable over a large majority of island out from Honiara, and, PAOA FM at 97.7 in Honiara (also broadcasting on 107.5 in Auki), and, one community FM radio station, Gold Ridge FM on 88.7.

- Television

There are no TV services that cover the entire Solomon Islands but are available in six main centres in four of the nine Provinces. Satellite TV stations can be received. In Honiara, there is a free-to-air HD digital, analogue TV and online service called Telekom Television Limited, operated by Solomon Telekom Co. Ltd.. and rebroadcast a number of regional and international TV srevices including ABC Australia and BBC World News. Residents can also subscribe to SATSOL, a digital pay TV service, re-transmitting satellite television.

Music

Traditional Melanesian music in Solomon Islands includes both group and solo vocals, slit-drum and panpipe ensembles. Bamboo music gained a following in the 1920s. In the 1950s Edwin Nanau Sitori composed the song "Walkabout long Chinatown", which has been referred to by the government as the unofficial "national song" of the Solomon Islands.[84] Modern Solomon Islander popular music includes various kinds of rock and reggae as well as island music.

Sport

Rugby union: The Solomon Islands national rugby union team has played internationals since 1969. It took part in the Oceania qualifying tournament for the 2003 and 2007 Rugby World Cups, but did not qualify on either occasion.

Association football: The Solomon Islands national football team has proved among the most successful in Oceania and is part of the OFC confederation in FIFA. They are currently ranked 141st out of 210 teams in the FIFA World Rankings. The team became the first team to beat New Zealand in qualifying for a play-off spot against Australia for qualification to the World Cup 2006. They were defeated 7–0 in Australia and 2–1 at home.

Futsal: Closely related to Association Football. On 14 June 2008, the Solomon Islands national futsal team, the Kurukuru, won the Oceania Futsal Championship in Fiji to qualify them for the 2008 FIFA Futsal World Cup, which was held in Brazil from 30 September to 19 October 2008. Solomon Islands is the futsal defending champions in the Oceania region. In 2008 and 2009 the Kurukuru won the Oceania Futsal Championship in Fiji. In 2009 they defeated the host nation Fiji 8–0 to claim the title. The Kurukuru currently hold the world record for the fastest ever goal scored in an official futsal match. It was set by Kurukuru captain Elliot Ragomo, who scored against New Caledonia three seconds into the game in July 2009.[85] They also, however, hold the less enviable record for the worst defeat in the history of the Futsal World Cup, when in 2008 they were beaten by Russia with two goals to thirty-one.[86]

Beach soccer: The Solomon Islands national beach soccer team, the Bilikiki Boys, are statistically the most successful team in Oceania. They have won all three regional championships to date, thereby qualifying on each occasion for the FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup. The Bilikiki Boys are ranked fourteenth in the world as of 2010, higher than any other team from Oceania.[87]

See also

References

- "Solomon Islands National Anthem Lyrics". Lyrics on Demand. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "National Parliament of Solomon Islands Daily Hansard: First Meeting – Eighth Session Tuesday 9th May 2006" (PDF). www.parliament.gov.sb. 2006. p. 12. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/solomon-islands#/?affiliations_religion_id=11&affiliations_year=2010®ion_name=All%20Countries&restrictions_year=2016

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Solomon Islands". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Population, total - Solomon Islands | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Alvaro de Mendaña de Neira, 1542?–1595". Princeton University Library. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 6 The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. ISBN 9781925022032.

- Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. P. 897

- "Lord GORONWY-ROBERTS, speaking in the House of Lords, HL Deb 27 April 1978 vol 390 cc2003-19". Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- HOGBIN, H. In, Experiments in Civilization: The Effects of European Culture on a Native Community of the Solomon Islands, New York: Schocken Books, 1970

- ‘International Encyclopedia of Comparative Law: Instalment 37’ edited by K. Zweigert, S-65

- The British Solomon Islands Protectorate (Name of Territory) Order 1975

- John Prados, Islands of Destiny, Dutton Caliber, 2012, p,20 and passim

- Sheppard, Peter J. "Lapita Colonization Across the Near/Remote Boundary" Current Anthropology, Vol 53, No. 6 (Dec 2011), p. 800

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (2002). On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23461-8

- Robert Langdon (ed.) Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, (1984), Camberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, pp.229–232 ISBN 0-86784-471-X.

- Judith A. Bennett, Wealth of the Solomons: a history of a Pacific archipelago, 1800–1978, (1987), Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, pp.24–31 & Appendix 3.ISBN 0-8248-1078-3

- Bennett, 27–30; Mark Howard, "Three Sydney whaling captains of the 1830s," The Great Circle, 40 (2) December 2018, 83–84.

- "History of the Solomon Islands". Retrieved 10 December 2013

- "Operation Watchtower: Assault on the Solomons" War in the Pacific: The First Year. U.S. National Park Service, 2004.

- The Commonwealth, Solomon Islands : History,https://thecommonwealth.org/our-member-countries/solomon-islands/history

- "Cap – Anu". Rspas.anu.edu.au. 14 December 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- "THE TOWNSVILLE PEACE AGREEMENT". Commerce.gov.sb. 15 October 2000. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Pacific Islands: PINA and Pacific". 10 November 2003. Archived from the original on 10 November 2003.

- Pillars and Shadows: Statebuilding as Peacebuilding in Solomon Islands, J. Braithwaite, S. Dinnen, M.Allen, V. Braithwaite & H. Charlesworth, Canberra, ANU E Press: 2010.

- Spiller, Penny: "Riots highlight Chinese tensions", BBC News, Friday, 21 April 2006, 18:57 GMT

- "Solomon Islands earthquake and tsunami", Breaking Legal News – International, 4 March 2007

- "Aid reaches tsunami-hit Solomons", BBC News, 3 April 2007

- "Quake lifts Solomons island metres from the sea". Archived from the original on 17 April 2007.

- "CIA – The World Factbook – Solomon Islands". Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Sireheti, Joanna., & Joy Basi, – "Solomon Islands PM Defeated in No-Confidence Motion", – Solomon Times, – 13 December 2007

- Tuhaika, Nina., – "New Prime Minister for Solomon Islands", – Solomon Times, – 20 December 2007

- "Solomon Islands parliament elects new PM", – ABC Radio Australia, – 20 December 2007

- Boyce, Hayden (20 September 2014). "Turks & Caicos Islands Chief Justice Edwin Goldsbrough Resigns". Turks & Caicos Sun. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- Lyons, Kate (16 September 2019). "China extends influence in Pacific as Solomon Islands break with Taiwan". theguardian.com. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Freedom of the press in Indonesian-occupied West Papua". The Guardian. 22 July 2019.

- Fox, Liam (2 March 2017). "Pacific nations call for UN investigations into alleged Indonesian rights abuses in West Papua". ABC News.

- "Pacific nations want UN to investigate Indonesia on West Papua". SBS News. 7 March 2017.

- "Goodbye Indonesia". Al-Jazeera. 31 January 2013.

- "Fiery debate over West Papua at UN General Assembly". Radio New Zealand 2017. 27 September 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "Homosexuality to remain illegal in Samoa, Solomon Islands and PNG", Radio Australia, 21 October 2011

- "Sectors". Commonwealth of Nations. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "Solomon Island Communities Build Potable Water Systems to Improve Livelihoods – Solomon Islands". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "JMP". washdata.org. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Projects : Solomon Islands Rural Development Program II | The World Bank". www.projects.worldbank.org. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "Forest area (% of land area) - for all countries". www.factfish.com.

- quantity "Coconuts, production quantity (tons) - for all countries" Check

|url=value (help). www.factfish.com. - quantity "Solomon Islands: Cocoa beans, production quantity (tons)" Check

|url=value (help). www.factfish.com. - palm%20 fruit%2C%20production%20 quantity "Solomon Islands: Oil palm fruit, production quantity (tons)" Check

|url=value (help). www.factfish.com. - quantity "Solomon Islands: Taro, production quantity (tons)" Check

|url=value (help). www.factfish.com. - quantity "Solomon Islands: Rice, paddy, production quantity (tons)" Check

|url=value (help). www.factfish.com. - "Solomon Islands: Yams, production quantity (tons)". www.factfish.com.

- "Solomon Islands: Bananas, production quantity (tons)". www.factfish.com.

- "Solomon Islands: Tobacco, production quantity (tons)". www.factfish.com.

- "Spices, others, production quantity (tons) - for all countries". www.factfish.com.

- "Keine Lust auf Massentourismus? Studie: Die Länder mit den wenigsten Urlaubern der Welt". TRAVELBOOK (in German). 10 September 2018.

- Paradise, Volume 4, July–August 2019, p. 128. Port Moresby 2019.

- "Currency as Cultural Craft: Shell Money – The Official Globe Trekker Website". The Official Globe Trekker Website. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Solomon Islands Solar: A New Microfinance Concept Takes Root. Renewable Energy World. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- Samisoni Pareti: Solomons, issue 80, S. 10. Honiara 2019.

- Südsee, p. 41. Nelles Verlag, München 2011

- CIA World Factbook. Country profile: Solomon Islands. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- Ethnologue report for Solomon Islands. Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2007". State.gov. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Ahmadiyya Solomon Islands". Ahmadiyya.org.au. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Human Development Report 2009 – Solomon Islands Archived 15 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- Loury, Ellen (7 May 2012). "Blond Afro Gene Study Suggests Hair Color Trait Evolved at Least Twice". Huffington Post. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Kenny EE; et al. (4 May 2012). "Melanesian Blond Hair is Caused by an Amino Acid Change in TYRP1". Science. 336 (6081): 554. Bibcode:2012Sci...336..554K. doi:10.1126/science.1217849. PMC 3481182. PMID 22556244.

- Norton HL; et al. (June 2006). "Skin and Hair Pigmentation Variation in Island Melanesia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 130 (2): 254–268. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20343. PMID 16374866.

- Loury, Erin (3 May 2012). "The Origin of Blond Afro in Melanesia". AAAS. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "Solomon Islands" Archived 30 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, United States Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Solomon Islands Population Characteristics" (PDF). Spc.int. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "Home – University of the South Pacific". 9 November 2005. Archived from the original on 9 November 2005.

- "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- "Solomon Islands country profile". BBC News. 31 July 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Ming, Mikaela A.; Stewart, Molly G.; Tiller, Rose E.; Rice, Rebecca G.; Crowley, Louise E.; Williams, Nicola J. (2016). "Domestic violence in the Solomon Islands". Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 5 (1): 16–19. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.184617. ISSN 2249-4863. PMC 4943125. PMID 27453837.

- "WHO 2011 report on gender based violence report in the Solomon Islands" (PDF).

- "WHO Solomon Islands GBV report 2013" (PDF).

- "Solomon Islands launches new domestic violence law". Radio New Zealand. 8 April 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- "Solomon Islands country profile". BBC News. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Wakabauti long Chinatown": The song, the composers, the storyline" Archived 18 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Office of the Prime Minister of Solomon Islands

- "RAGOMO BEATS WORLD RECORD....to score the fastest futsal goal", Solomon Star, 15 July 2009

- "Russia Beats Kurukuru 31–2", Solomon Times, 7 October 2008

- "Bilikiki ranked fourteenth in the world" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Solomon Star, 29 January 2010

External links

- Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet

- "Solomon Islands". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Moore, Clive. "Solomon Islands Historical Encyclopaedia 1893–1978".

- Latest Earthquakes – United States Geological Survey

- Solomon Islands Act 1978 (25th May 1978): "to make provision for, and in connection with, the attainment by Solomon Islands of independence within the Commonwealth."

.svg.png)