Philippine Sea

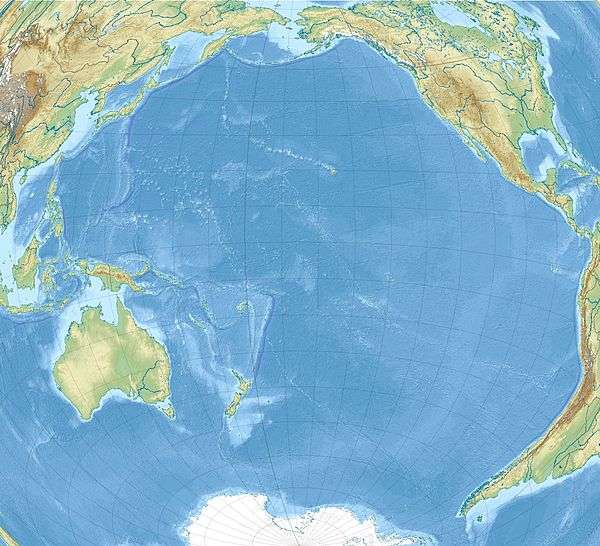

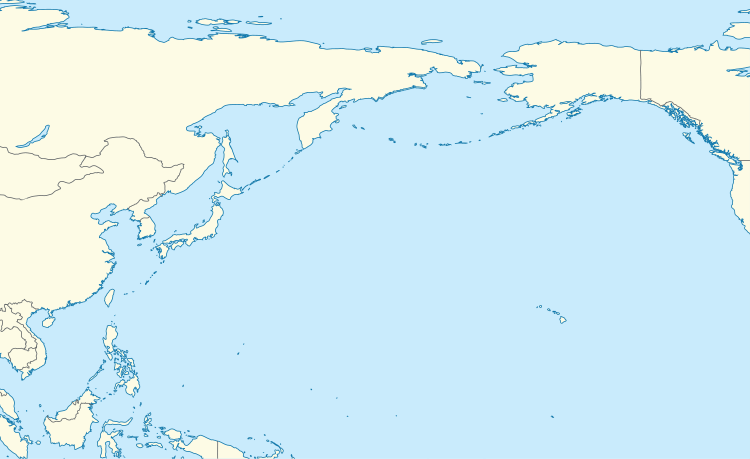

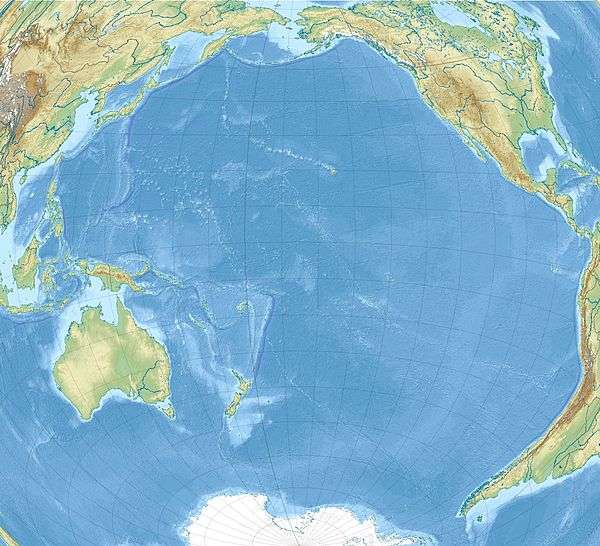

The Philippine Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean east/northeast of the Philippine archipelago (hence the name), occupying an estimated surface area of 5 million square kilometres (2 million square miles).[1] The Philippine Sea Plate forms the floor of the sea.[2] It is bordered by the first island chain to the west, which comprises the Ryukyu Islands in the northwest and Taiwan in the due west, and the Filipino islands of Luzon, Catanduanes, Samar, Leyte and Mindanao to the southwest; by the Japanese islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyūshū to the north; by the second island chain to the east, which comprises the Bonin and Iwo Jima in the northeast, the Marianas (including Guam, Saipan and Tinian) in the due east, and the Halmahera, Palau, Yap and Ulithi (of the Carolines) in the southeast; and by Indonesia's Morotai Island to the south.[3]

| Philippine Sea | |

|---|---|

| |

Philippine Sea Location within the Pacific Ocean  Philippine Sea Philippine Sea (North Pacific ) .svg.png) Philippine Sea Philippine Sea (Philippines) | |

| Coordinates | 20°N 130°E |

| Part of | Pacific Ocean |

| Basin countries | |

| Islands | List

|

| Trenches |

|

The sea has a complex and diverse undersea relief.[4] The floor is formed into a structural basin by a series of geologic faults and fracture zones. Island arcs, which are actually extended ridges protruding above the ocean surface due to plate tectonic activity in the area, enclose the Philippine Sea to the north, east and south. The Philippine archipelago, Ryukyu Islands, and the Marianas are examples. Another prominent feature of the Philippine Sea is the presence of deep sea trenches, among them the Philippine Trench and the Mariana Trench, containing the deepest point on the planet.

Geography

Location

The Philippine Sea has the Philippines and Taiwan to the west, Japan to the north, the Marianas to the east and Palau to the south. Adjacent seas include the Celebes Sea which is separated by Mindanao and smaller islands to the south, the South China Sea which is separated by Philippines, and the East China Sea which is separated by the Ryukyu Islands.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the Philippine Sea as "that area of the North Pacific Ocean off the Eastern coasts of the Philippine Islands", bounded as follows:[5]

On the west. By the eastern limits of the East Indian Archipelago, South China Sea and East China Sea.

On the north. By the southeast coast of Kyushu, the southern and eastern limits of the Inland Sea and the south coast of Honshu Island.

On the east. By the ridge joining Japan to the Bonin, Volcano and Ladrone (Mariana) Islands, all these being included in the Philippine Sea.

On the south. By a line joining Guam, Yap, Pelew (Palau) and Halmahera Islands.

Geology

The Philippine Sea Plate forms the floor of the Philippine Sea. It subducts under the Philippine Mobile Belt which carries most of the Philippine archipelago and eastern Taiwan. Between the two plates is the Philippine Trench.

Marine biodiversity

The Philippine Sea has a marine territorial scope of over 679,800 square kilometres (262,500 sq mi), and an EEZ of 2.2 million km2. Attributed to an extensive vicariance and island integrations, the Philippines contains the highest number of marine species per unit area relative to the countries within the Indo-Malay-Philippines Archipelago, and has been identified as the epicenter of marine biodiversity.[6] With its inclusion in the Coral Triangle, the Philippine Sea encompasses over 3,212 fish species, 486 coral species, 800 seaweed species, and 820 benthic algae species, wherein the Verde Island Passage is dubbed as "the center of the center of marine fish biodiversity".[7] Within its territory, thirty-three endemic species of fish have been identified, including the blue-spotted angelfish (Chaetodontoplus caeruleopunctatus) and the sea catfish (Arius manillensis).[8] The Philippine marine territory has also become a breeding and feeding ground for endangered marine species, such as the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the dugong (Dugong dugon), and the megamouth shark (Megachasma pelagios).[7]

Coral Triangle

The Coral Triangle, or the Indo-Malayan Triangle, is considered as the global center of marine biodiversity, its total oceanic area approximately 2 million square kilometers.[9] It encompasses the tropical waters of Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands.[10] The Philippines is found at the apex of the Coral Triangle, taking up 300,000 square kilometres (120,000 sq mi) of the Coral Triangle,[11] with the country's coral reef area in the Coral Triangle ranging from 10,750 square kilometres (4,150 sq mi) to 33,500 square kilometres (12,900 sq mi), which has over 500 species of scleractinian or stony corals, and 12 endemic coral species have been identified here as well.[9]

The Coral Triangle houses 75% of the world's coral species which is estimated to be at around 600 different species, along with over 2000 different types of reef fish. It is also home to six of the world's seven species of marine turtles, namely hawksbill, loggerhead, leatherback, green turtle, olive ridley, and sea turtle.[12] Up until now, there is no single explanation of the diversity found in the Coral Triangle, as most researchers have attributed the diversity to geological occurrences like plate tectonics.[13]

It also helps in providing and supporting the livelihoods of 120 million people, and is able to provide food to the Philippine coastal communities and millions more worldwide.[12] The whale shark tourism in the Coral Triangle also helps provide a steady source of income for the community.[12] Apart from the Philippines, the marine sources found in the Coral Triangle have high economic value across the globe. Countries surrounding the Coral Triangle also help provide their locals with technical assistance and capability to build toward conservation and sustainability for food security, livelihoods, biodiversity and economic development.[10]

Climate change also continuously affects the coastal ecosystem found in the Coral Triangle, as it contributes to rising sea levels and ocean acidification, thus endangering marine animals like fish and turtles. Consequently, this also has a negative effect on local livelihoods such as fishing and tourism. Corals are not able to adapt and survive if water will keep on warming, as this makes the corals absorb more carbon dioxide, altering pH balance making it acidic.[12]

Biology

The Philippine Sea hosts an exotic marine ecosystem. About five hundred species of hard and soft corals occur in the coastal waters and 20 per cent of the worldwide known shellfish species are found in Philippine waters. Sea turtles, sharks, moray eels, octopuses and sea snakes along with numerous species of fish such as tuna can commonly be observed. Additionally, the Philippine Sea serves as spawning ground for Japanese eel, tuna and different whale species.[4]

Biodiversity

Human impact

The Philippine Sea is both a centre of marine biodiversity as well as a biodiversity hotspot. At least 418 species are being threatened because of unsustainable practices. According to the Asia Development Bank, there is a 90% reduction in marine life in the area, due to the various economic procedures being performed. The Philippine Sea he terminal point of sewage pipelines from the cities. Mangrove forests are also being removed for the sake of both property development and wood production. Mercury wastes and mining runoff also end up within the Philippine Sea. These are some of the reasons why the Philippines is ranked as one of the highest in reef degradation.[14]

Climate change

The rise in temperature change caused shifts in the marine ecosystems. The ideal temperature for coral to is 24-29 degrees Celsius. If the water temperature goes above or below this threshold, the coral growth would slow down or even die. As fish and other marine life rely on corals for sustenance and habitat, communities that rely on fishing are heavily affected as well.[15] As the Philippine Sea is within the Pacific Ring of Fire, the physical damage caused by typhoons coming from the east can further destroy the marine habitats.[16]

History

The first European to navigate the Philippine Sea was Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, who named it Mar Filipinas when he and his men were in the Mariana Islands prior to the exploration of the Philippines. Later it was discovered by other Spanish explorers from 1522 to 1565 and the site of the famous galleon trade route.

Between 19 and 20 June 1944, the Battle of the Philippine Sea (a very large and decisive World War II naval battle between Japan and the United States) took place in the eastern Philippine Sea, near the Mariana Islands. The aircraft carriers Taihō, Shōkaku, Junyō, Hiyō and Ryuho were bombed, torpedoed and sunk by American carrier-based planes and assaulted from other naval vessels. The aerial part of the Battle of the Philippine Sea was nicknamed the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot" due to massive losses of Japanese aircraft and pilots. The battle facilitated the Allied conquests of Saipan, Guam and Tinian in the Marianas, Palau in the Southwest, and ultimately the Philippines.

It was not until 1989 that the Pentagon revealed the loss of the one-megaton nuclear bomb during the 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 incident.[17]

Following an escalation of the Spratly Islands dispute in 2011, various Philippine government agencies started using the neologism "West Philippine Sea" to refer to the South China Sea. However, a PAGASA spokesperson said that the sea to the east of the Philippines will continue to be called the Philippine Sea.[18]

Battles of the Philippine Sea

A historic battle between the naval fleets of the United States and Japan took place in the vicinity of the Philippine Sea. This was called The Battle of the Philippine Sea, and occurred near the Mariana Islands from 19–20 June 1944.[19] It was also the largest carrier-to-carrier battle in history which featured the United States Fifth Fleet and the 1st Mobile Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Aside from the navy, aerial activity was also present in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, as hundreds of aircraft from both countries fired at each other. The Americans indisputably won, and nicknamed the aerial war the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” due to the number of Japanese aircraft shot down.[20]

Japan struggled to recover from the severe damages of its imperial navy and air strength suffered from the battle. This heavily attributed to the victory of the United States in the Battle of the Philippine Sea which was a vital part of the Americans' reclamation of the Philippines, and the Mariana Islands from Japan.[21]

Economy

Fisheries

The Philippines depends on the Philippine Sea for one of its sources of food and livelihood. In the Coral Triangle area, the Philippines harvest seaweeds, milkfish, shrimp, oyster, mussel and live reef fish as aquaculture products. Fishermen also catch most fishes like small pelagics, anchovy, sardine, mackerel and tuna, among many other species found.[12]

Recent scientific expedition has found that the Benham Rise (also known as the Philippine Rise) within the sea is diverse in its marine ecosystem that it attracts migratory commercial fish like tuna, marlin and mackerel.[22] The Benham Rise is also considered as a rich fishing ground for fishermen from Aurora, Quezon and Bicol.[23] The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources thought it necessary to teach fishermen sustainable fishing so as to prevent the destruction of coral formations which could negatively affect the food chain of the migratory fish. They have considered migratory fish to be in quite of a high value, as, for example, a single blue tuna fin found in the Benham Rise, can be sold at ₱2,000 in the market.[22]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philippine Sea. |

References

- "Philippine Sea". Encarta. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- North Pacific Ocean

- "Philippine Sea". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- "Philippine Sea". Lighthouse Foundation. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- "Environmental Biology of Fishes". Springer Nature Switzerland. ISSN 0378-1909. Retrieved 4 November 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Goldman, Lee (10 August 2010). "A Biodiversity Hotspot in the Philippines". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Boquet, Yves (2017). The Philippine archipelago. Springer. p. 321. ISBN 9783319519265. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- State of the Coral Triangle : Philippines (PDF). Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank. 2014. ISBN 978-92-9254-518-5. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "NOAA PIFSC CRED in the Coral Triangle: Building capacity for application of an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "Economics of Fisheries and Aquaculture in the Coral Triangle" (PDF). Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank. 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Coral Triangle; Facts". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- The coral triangle and climate change : ecosystems, people and societies at risk : summary (PDF). Sydney NSW Australia: WWF Australia. May 2009. ISBN 978-1-921031-35-9. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Purdy, Elizabeth Rholetter. "Philippine Sea". http://rizal.lib.admu.edu.ph. Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science. Retrieved 20 July 2018. External link in

|website=(help) - "Philippine Seas" (PDF). Greenpeace. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- "How Is Climate Change Affecting the Philippines?". Climate Reality Project. climaterealityproject.org. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- "U.S. Confirms '65 Loss of H-Bomb Near Japanese Islands". The Washington Post. 9 May 1989.

- Quismundo, Tarra (13 June 2011). "South China Sea renamed in the Philippines". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- "Crowder, M. (2006). Dreadnoughts' FIERY FINALE. World War II, 21(5), 48". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Lambert, J. W. (2011). OLD-FASHIONED TURKEY SHOOT. Aviation History, 22(2), 22-29.

- Kennedy, D. M. (1999). Victory at sea. Atlantic, 283(3), 51-76.

- Dimacali, TJ (8 May 2017). "'Fish more important than gold' –BFAR on Benham Rise". GMA News. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Cinco, Maricar (19 March 2017). "Exploring Benham Rise's unknown treasures". Inquirer.net. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 4 November 2018.