Meghalaya subtropical forests

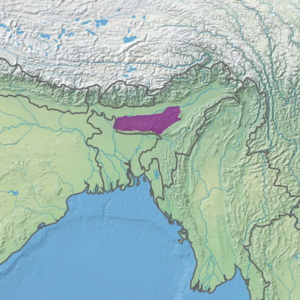

The Meghalaya subtropical forests is an ecoregion of Northeast India. The ecoregion covers an area of 41,700 square kilometers (16,100 sq mi), and despite its name, comprise not only the state of Meghalaya, but also parts of southern Assam, and a tiny bit of Nagaland around Dimapur. It also contains many other habitats than subtropical forests, but the montane subtropical forests found in Meghalaya is an important biome, and was once much more widespread in the region, and for these reasons chosen as the most suitable name.[2][3] The scientific designation is IM0126.

| Meghalaya subtropical forests ecoregion | |

|---|---|

| |

Ecoregion territory (in purple) | |

| Ecology | |

| Biome | tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest |

| Borders | Mizoram-Manipur-Kachin rain forests, Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests and Lower Gangetic plains moist deciduous forests |

| Bird species | 659 |

| Mammal species | 110 |

| Geography | |

| Area | 41,700 km2 (16,100 sq mi) |

| Country | India |

| States | Meghalaya, Assam and Nagaland |

| Geology | Limestone formations (Karbi-Meghalaya plateau and westward arm of the Patkai Range) |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Vulnerable |

| Protected | 1.07 (2.78)%[1] |

The Meghalaya subtropical forests are part of the larger Indo-Burma biological hotspot with many endemic species not found anywhere else in the world. Together with the Western Ghats, Northeast India are the only two regions of India, endowed with rainforest. For these, and other, reasons, protection and conservation of the Meghalaya subtropical forests are important on a local, national, regional and even global level.

The ecoregion is one of the most species-rich areas in India, with a rich diversity of birds, mammals, and plants in particular. The lowlands holds mostly tropical forests, while the hills and mountains, that comprise most of the area, are covered in grasslands and several distinct types of forest habitats, including subtropical moist broadleaf forests in some of the montane areas above 1,000 metres. The region is one of the wettest areas in the world, with some places, notably Mawsynram and Cherrapunji in the south of Meghalaya, receiving up to eleven meters of rain in a year.

The Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests ecoregion lies to the north, the Mizoram-Manipur-Kachin rain forests ecoregion lies to the east, and the Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests ecoregion lies to the west and south in Bangladesh.

Flora

The elevated and damp forest ecoregion is a center of diversity for the tree genera Magnolia and Michelia, and the families Elaeocarpaceae and Elaeagnaceae. Over 320 species of orchids are native to Meghalaya. The endemic pitcher plant (Nepenthes khasiana) is now an endangered species. About 3,128 flowering plant species have been reported from the state, of which 1,236 are endemic.[4] In the later half of the 1800s, Joseph Dalton Hooker, a British botanist and explorer, made a huge taxonomic collection for the Kew Herbarium from Khasi and Jaintia Hills and remarked the place as one of the richest biodiversity spots in India, perhaps in all of Asia as well.[5] Meghalaya state is rich in medicinal plant species, but the natural occurrence of most medicinal plants has decreased due to habitat loss. A total of 131 RET (Rare, Endemic and Threatened) medicinal plant species, including 36 endemic and 113 species under different threat categories, are found within Meghalaya.[6]

As in other rural areas of India, Meghalaya villages have an ancient tradition of nurturing sacred groves. These are sacred spots within the forest where medicinal and other valued plants are grown and harvested sustainably, and they present a very high biodiversity. In Meghalaya these sacred groves are known as Law Kyntang or Law Lyngdoh.[7][8]

- The Meghalaya forests near the border with Bangladesh

Streams and waterfalls are plentiful

Streams and waterfalls are plentiful

In the seasonal streams, heavy rain flushes all soil away, leaving only rocks and boulders.

In the seasonal streams, heavy rain flushes all soil away, leaving only rocks and boulders.

Orchids (unidentified) growing wild in the forests

Orchids (unidentified) growing wild in the forests.jpg) A forest path near Cherrapunji.

A forest path near Cherrapunji. Jhum cultivation, a slash-and-burn technique, is practised by the hill tribes as an ancient tradition.

Jhum cultivation, a slash-and-burn technique, is practised by the hill tribes as an ancient tradition.

Fauna

The montane ecoregion is home to a diverse mix of birds, with a total of 659 species recorded as of 2017. Some of the birds living here are endemic to the Indo-Burma ecoregion, and quite a few species are threatened or near threatened on a global scale. Of these, two kinds of vultures, the Oriental White-backed Vulture and the Slender-billed Vulture, are both in need of extra protection as critically endangered species near extinction. The Meghalaya forests are not only important as a wildlife refuge for birds, it is also important to migratory birds on their long-distance flights.[10][11]

The subtropical forests presents a diverse range of reptiles, with as much as 56 species of known snakes, in addition to several lizards and turtles. The Tokay Gecko, among the largest geckos in the world, are here, as are three different kinds of monitor lizards, all of them to be protected since 1972, and a new species of skink (sphenomorphus apalpebratus) was discovered in the forests as late as 2013. Both Brahminy Blind snake and Copperhead Rat Head are among the more common snakes encountered in the forests, but there are several venomous and deadly serpents too, such as the Green Pit viper and the King Cobra, the longest venomous snake in the world. Many of the snake species here are elusive (and rare), such as the Cherrapunji keelback, Khasi keelback or Khasi earth snake.[10]

The damp and moist environment of the Meghalaya forests also supports what is the most diverse range of amphibians in North-east India, with a total of 33 recorded species living here. The two frog species Shillong bush frog and Khasi Hill toad are endemic, and both rare and threatened.[10]

Molluscs are thriving in the moist conditions and are abundant throughout, both on land and in the water, As much as 223 species has been recorded by science, and many of the land-dwelling molluscs are endemic to Meghalaya. Fresh water molluscs are generally considered a good indicator species of clean waters, and Meghalaya's waterways are home to 35 species, with a lot of paludomus-snails in the hill streams. Several types of fresh water snails are part of the hill tribes diet, including the large bellamya bengalensis snails.[10]

Situated between the mighty Brahmaputra in the north and the Barak River to the south, Meghalaya's many waterways are also home to a diverse range of fish species. 152 known species has been observed as of 2017. Two types of mahseer (neolissochilus and tor) are fished for sport.[10]

The subtropical forests are home to 110 species of mammals, none of which are endemic. By far, most of these species comprise smaller mammals, in particular bats and small carnivores, and the population of large mammals is comparatively sparse.[10] The Western hoolock gibbons in the forests of Meghalaya are globally endangered, and also threatened in this particular habitat, but they have a special place among the local tribes who cherish their song.[12] Other large mammals important to conservation here includes the tiger (Panthera tigris), clouded leopard (Pardofelis nebulosa), Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), dhole or Asiatic wild dog (Cuon alpinus), sun bear (Ursus malayanus), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata), Indian civet (Viverra zibetha), Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla), Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata), Assamese macaque (Macaca assamensis), bear macaque (Macaca arctoides), and capped leaf monkey (Semnopithecus pileatus).

_(8364842473).jpg) Blue Peacock butterfly (papilio arcturus). Several species of butterflies and moths are living in the forests here.

Blue Peacock butterfly (papilio arcturus). Several species of butterflies and moths are living in the forests here. Scarce vine hawkmoth (Ampelophaga khasiana, underside). This species can have a wingspan of more than 10 cm.

Scarce vine hawkmoth (Ampelophaga khasiana, underside). This species can have a wingspan of more than 10 cm. Marbled map (Cyrestis cocles)

Marbled map (Cyrestis cocles).jpg) The woodlands are home to several kinds of snakes, including some large poisonous types. (here Yellow-speckled pit viper)

The woodlands are home to several kinds of snakes, including some large poisonous types. (here Yellow-speckled pit viper) Capped leaf monkies

Capped leaf monkies.jpg) Asiatic wild dogs (dholes)

Asiatic wild dogs (dholes) Clouded leopards are the state animal of Meghalaya

Clouded leopards are the state animal of Meghalaya Sloth bear. The forests are also home to several species of large (and dangerous) mammals.

Sloth bear. The forests are also home to several species of large (and dangerous) mammals. Asian elephants has found a refuge in the Meghalaya subtropical forests

Asian elephants has found a refuge in the Meghalaya subtropical forests

Protected areas

The ecoregion has several national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, but they are all of relatively small size.[13] In addition, Meghalaya holds a total of 712.74 km2 reserved forest and 12.39 km2 protected forest.[14]

- Balphakram National Park, a large national park in south Garo Hills

- Nokrek National Park, in east Garo Hills

- Nongkhyllem Wildlife Sanctuary

- Siju Wildlife Sanctuary, a bird sanctuary

- Narpuh Wildlife Sanctuary[15][16]

- Baghmara Pitcher Plant Sanctuary, a small sanctuary park of 2 hectares

Some of the reserved forest is used by locals for voluntary wildlife reserves, in particular to help save the threatened Hoolock Gibbons.[17][12][18] Other parts of the reserved forest is maintained as wildlife corridors, for elephants for example, and to safeguard against damaging habitat fragmentation.[19]

Related parks and gardens

The nature and wildlife of Meghalaya, and the montane rainforests of the ecoregion in particular, is of interest to the tourist industry in the area, and to cater for these interests, an Eco Park has been created in Cherrapunjee.[20] Several waterfalls and caves of the region are also of interest to nature loving tourists.[21]

The state of Meghalaya maintains a total of three botanical gardens, all three are in the capital of Shillong.[22]

Conservation status

The Meghalaya subtropical forest ecoregion is part of the larger Indo-Burma biological hotspot with many endemic species not found anywhere else in the world. Together with the Western Ghats, Northeast India are the only two regions of India, endowed with rainforest. For these, and other, reasons, protection and conservation of the Meghalaya subtropical forests are important on a local, national, regional and even global level.[23][24]

As seen in other rainforests of the world, deforestation occurs on an alarming scale in Meghalaya too, with accelerated clearcutting for agriculture, industry, mining and infrastructure projects since the 1990s. Apart from the obvious loss of primary forest, this has also caused local problems with soil erosion and fragmentation of habitats. The clearcut areas in Meghalaya are sometimes allowed to regrow, but the second-growth forests are much less species-rich (both flora and fauna), than the original forest. In addition to these problematic issues, the dense forest habitats of Meghalaya are also dwindling because of tree thinning. This forestry practise puts extra pressure on species that can only thrive in dense forests. The root motivation for the increase in these environmentally changing practises are thought to be a high population growth and increased industrial activity in Meghalaya.[25]

Sources

- Wikramanayake, Eric; Eric Dinerstein; Colby J. Loucks; et al. (2002). Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a Conservation Assessment, Island Press; Washington, DC.

- Aabid Hussain Mir, Krishna Upadhaya and Hiranjit Choudhury (2014): Diversity of endemic and threatened ethnomedicinal plant species in Meghalaya, North-East India, Int. Res. J. Env. Sc. 3(12): 64-78.

- Hooker, J.D. 1872-1897. The Flora of British India, 7 vols. L. Reeva and Company, London.

- Khan, M.L., Menon, S. and Bawa, K.S. 1997. Effectiveness of the protected area network in biodiversity conservation: A case study of Meghalaya state, Biodiversity and Conservation 6: 853-868.

- Chettri N., Sharma E., Shakya B., Thapa (2010). Biodiversity in the Eastern Himalayas: Status, Trends and Vulnerability to Climate Change (PDF). ICIMOD Books.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Notes and references

- Note: The figure in parentheses also includes reserved forest areas.

- "Southern Asia: Eastern India". World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Note: The Meghalaya subtropical forests [IM0126] ecoregion was chosen by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to be almost identical to the previous biogeographical unit North-East Hills (19b) from MacKinnon (March 1997). Protected Areas Systems Review of the Indo-Malayan Realm. The Asian Bureau for Conservation Limited.

- Khan et al., 1997

- Hooker, 1872-97

- Mir et al., 2014

- Upadhaya, K.; Pandey, H.N.; Law, P.S.; Tripathi, R.S. (2003). "Tree diversity in sacred groves of the Jaintia hills in Meghalaya, northeast India". Biodiversity and Conservation. 12 (3): 583–597. doi:10.1023/A:1022401012824.

- Tiwari, BK; Tynsong, H.; Lynser, MB (2010). "Forest Management Practices of the Tribal People of Meghalaya, North-East India". Journal of Tropical Forest Science. 22 (3): 329–342. JSTOR 23616662.

- "Spotted-Leaf Sonerila". Flowers of India (FOI). Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Threatened Faunal Species in Meghalaya". Meghalaya Biodiversity Board. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- "Meghalaya" (PDF). Important Bird Areas In India. Government of India, Ministry of Environment & Forests. 7 October 2004. pp. 754–76. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Bikash Kumar Bhattacharya (23 May 2019). "For India's imperiled apes, thinking locally matters". Mongabay. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- "List of Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks in Meghalaya". Pin Code India. 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- "Reserved and Protected Forests in Meghalaya". Forest and Environment Department, Meghalaya Government. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- Note: Narpuh Wildlife Sanctuary was created in 2015 but is rarely presented as a wildlife sanctuary, perhaps because of local opposition.

- "Villagers to move SC against Narpuh eco-sensitive zone". Highland Post. 5 November 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Irina Ningthoujam (20 April 2007). "Tribesmen in Sebalgre in Meghalaya declare their first notified Village Wildlife Reserve". E-Pao. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Sibi Arasu (25 March 2019). "Meghalaya's community-managed forests protect endangered Western Hoolock Gibbon". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- "Rewak-Emangre Corridor is declared a Village Reserve Forest". World Land Trust. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- "Cherrapunji - Eco Park". India Beacons. 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Wild Life". Meghalaya Tourism. 5 October 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Botanical Gardens in Meghalaya". Meghalaya Biodiversity Board. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Biodiversity in Meghalaya". Meghalaya Biodiversity Board. 18 December 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- Saikia, Purabi & Khan, Mohammed (2017). "Floristic diversity of Northeast India and its conservation". Plant Diversity in the Himalaya Hotspot Region. Central University of Jharkhand, Dr. Hari Singh Gour University. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh. pp. 1023–1036.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Anwaruddin Choudhury (October 2003). "Meghalaya's Vanishing Wilderness". Sanctuary Asia. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meghalaya subtropical forests ecoregion. |

- "Meghalaya subtropical forestss [IM0126] ecoregion". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- "Ecoregions 2017". Resolve.

Geographical ecoregion maps and basic info. - "Meghalaya Biodiversity Board". Government of Meghalaya.

- Flora of Meghalaya (Government of Meghalaya)