Jakarta

Jakarta (/dʒəˈkɑːrtə/; Indonesian pronunciation: [dʒaˈkarta] (![]()

Jakarta | |

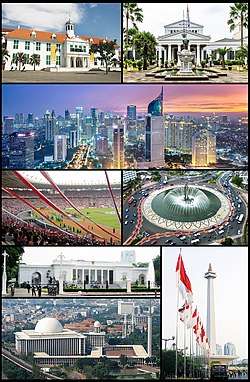

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Jakarta Old Town, National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta Skyline, Gelora Bung Karno Stadium, Hotel Indonesia Roundabout, Merdeka Palace, Monumen Nasional, and Istiqlal Mosque with Jakarta Cathedral. | |

.svg.png) Flag | |

| Coordinates: 6°12′S 106°49′E | |

| Founded | 22 June 1527[1] |

| City status | 4 March 1621[1] |

| Province status | 28 August 1961[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Special administrative area |

| • Body | DKI Jakarta Provincial Government |

| • Governor | Anies Baswedan |

| • Vice Governor | Ahmad Riza Patria |

| • Legislative | Jakarta Regional People's Representative Council |

| Area | |

| • Special Capital Region | 662.33 km2 (255.73 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 6,392 km2 (2,468 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 34th in Indonesia |

| Elevation | 8 m (26 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • Special Capital Region | 10,770,487 |

| • Rank | 6th in Indonesia |

| • Density | 14,464/km2 (37,460/sq mi) |

| • Metro (2015 estimate)[3] | 31,689,592 |

| • Metro density | 4,958/km2 (12,840/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (Indonesia Western Time) |

| HDI | |

| HDI rank | 1st in Indonesia (2019) |

| GRP Nominal | |

| GDP PPP (2019) | |

| GDP rank | 1st in Indonesia (2019) |

| Nominal per capita | US$ 19,029 (2019)[4] |

| PPP per capita | US$ 62,549 (2019)[4] |

| Per capita rank | 1st in Indonesia (2019) |

| Website | jakarta.go.id |

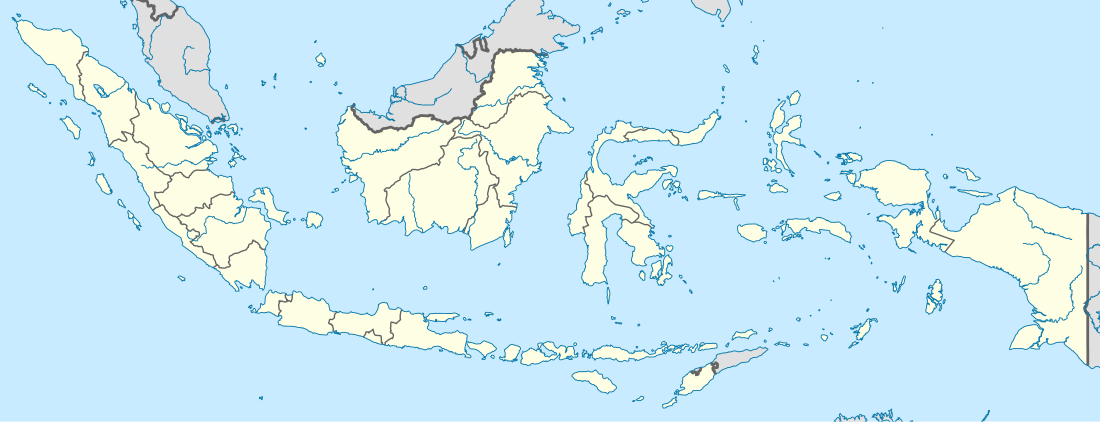

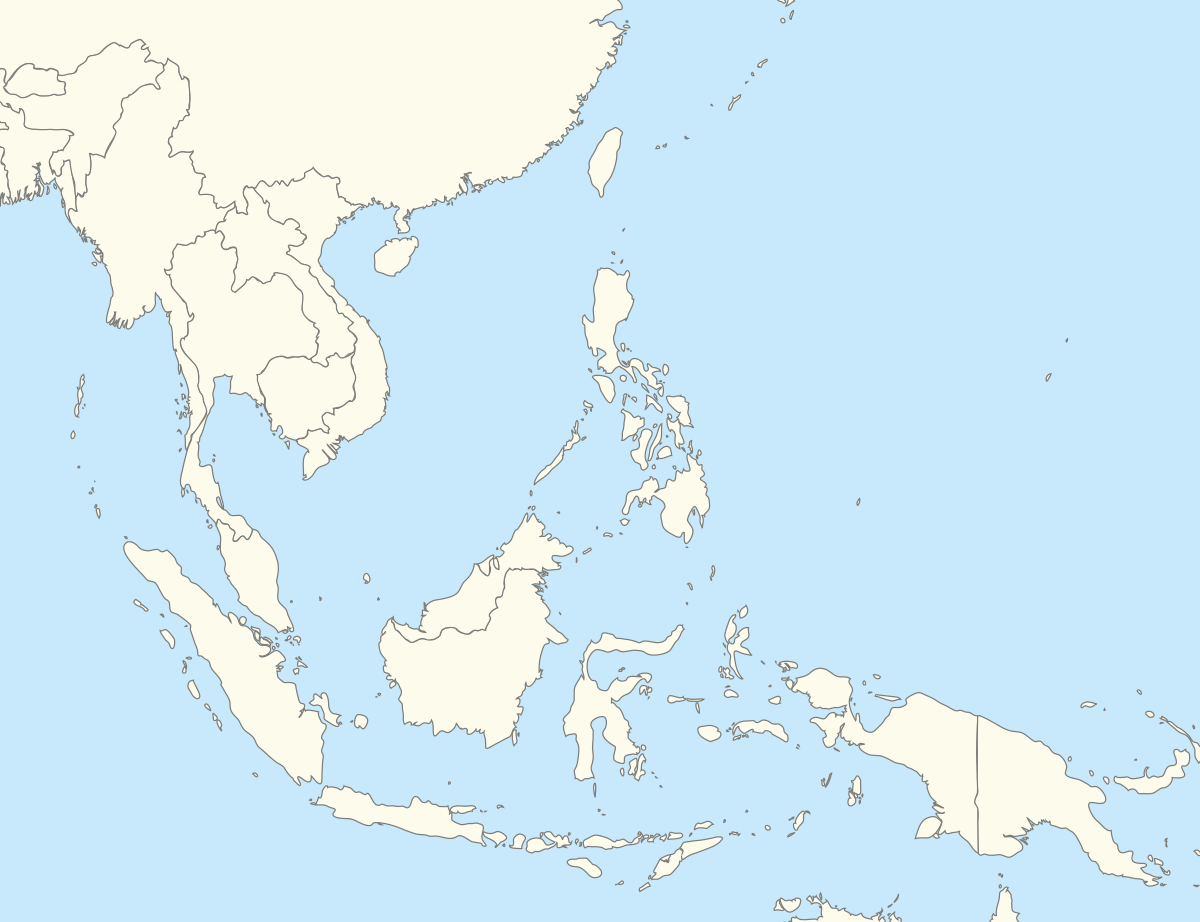

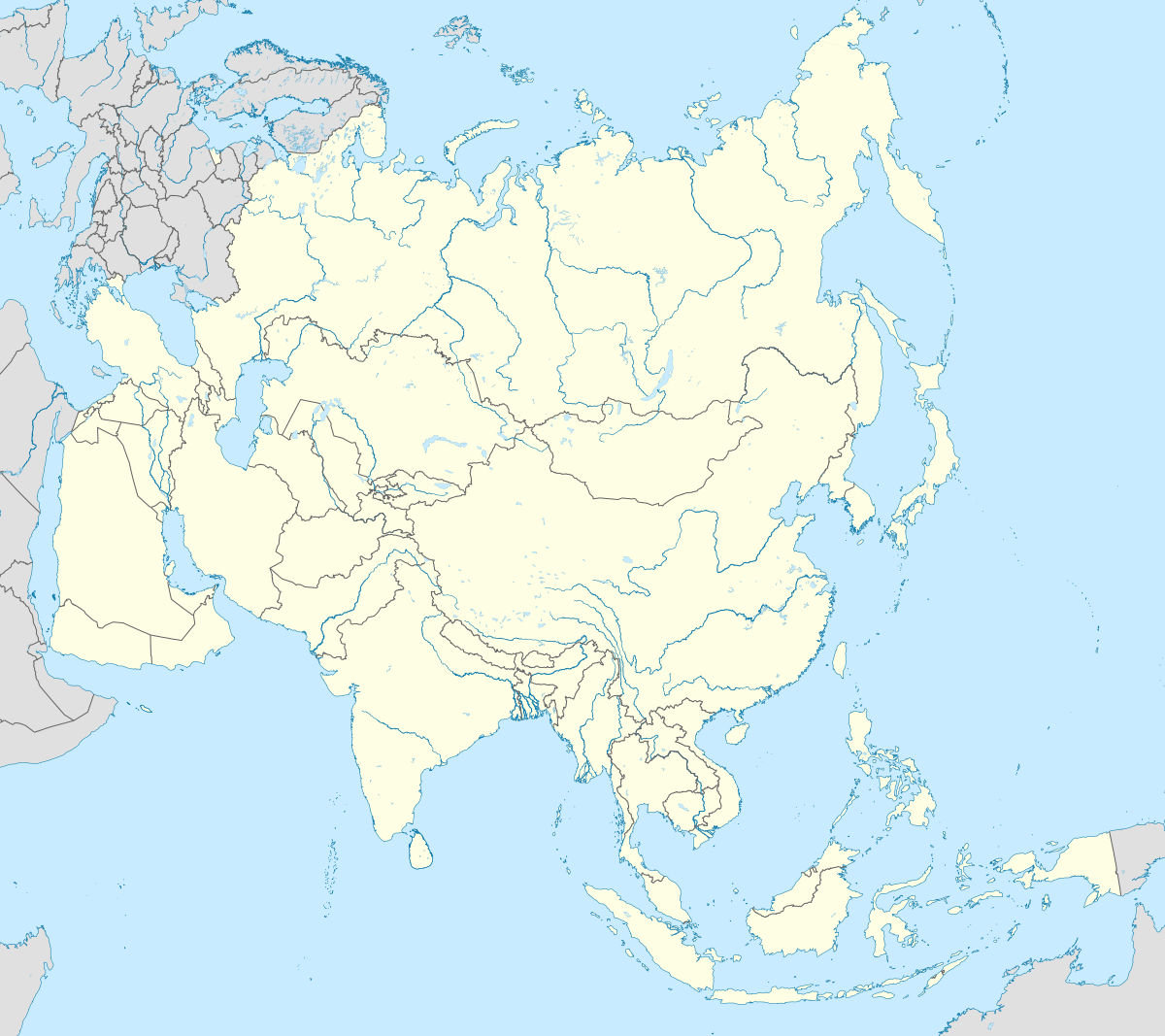

Established in the fourth century as Sunda Kelapa, the city became an important trading port for the Sunda Kingdom. It was the de facto capital of the Dutch East Indies when it was known as Batavia. Jakarta is officially a province with special capital region status, though it is commonly referred to as a city. Its provincial government consists of five administrative cities and one administrative regency. Jakarta is an alpha world city[10] and is the seat of the ASEAN secretariat,[11] making it an important city for international diplomacy.[12] Financial institutions such as the Bank of Indonesia, Indonesia Stock Exchange, and corporate headquarters of numerous Indonesian companies and multinational corporations are located in the city. Jakarta has grown more rapidly than Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok and Beijing.[13] In 2017, the city's GRP PPP was estimated at US$483.4 billion.[14][15]

Jakarta's prime challenges include rapid urban growth, ecological breakdown, gridlocked traffic, congestion, and flooding.[16] Additionally, Jakarta is sinking up to 17 cm (6.7 inches) per year, which, coupled with the rising of sea levels, has made the city more prone to flooding. It is also one of the fastest-sinking capitals in the world.[17] In August 2019, President Joko Widodo announced a move of the capital to the province of East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo.[18]

Etymology

Jakarta has been home to multiple settlements. Below is the list of names used during its existence.

- Sunda Kelapa (397–1527)

- Jayakarta (1527–1619)

- Batavia (1619–1942)

- Djakarta (1942–1972)

- Jakarta (1972–present)

Its name 'Jakarta' derives from the word Jayakarta (Devanagari: जयकर्त) which is ultimately derived from the Sanskrit जय jaya (victorious)[19] and कृत krta (accomplished, acquired),[20] thus Jayakarta translates as 'victorious deed', 'complete act' or 'complete victory'. It was named after Muslim troops of Fatahillah successfully defeated and drove out the Portuguese away from the city in 1527.[21] Before it was called Jayakarta, the city was known as 'Sunda Kelapa'. Tomé Pires, a Portuguese apothecary during his journey to East Indies, wrote the city name on his magnum opus as Jacatra or Jacarta.[22]

In the 17th century, the city was also known as Koningin van het Oosten (Queen of the Orient), for the urban beauty of downtown Batavia's canals, mansions and ordered city layout.[23] After expanding to the south in the 19th century, this nickname came to be more associated with the suburbs (e.g. Menteng and the area around Merdeka Square), with their wide lanes, green spaces and villas.[24] During the Japanese occupation, the city was renamed as Jakaruta Tokubetsu-shi (ジャカルタ特別市, Jakarta Special City).[25]

The official name used is Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta, which literally means Jakarta Capital Special Region.

History

Pre-colonial era

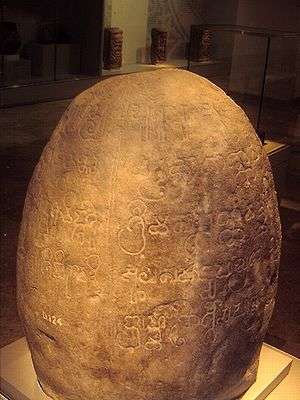

The north coast area of western Java including Jakarta was the location of prehistoric Buni culture that flourished from 400 BC to 100 AD.[26] The area in and around modern Jakarta was part of the 4th-century Sundanese kingdom of Tarumanagara, one of the oldest Hindu kingdoms in Indonesia.[27] The area of North Jakarta around Tugu became a populated settlement in the early 5th century. The Tugu inscription (probably written around 417 AD) discovered in Batutumbuh hamlet, Tugu village, Koja, North Jakarta, mentions that King Purnawarman of Tarumanagara undertook hydraulic projects; the irrigation and water drainage project of the Chandrabhaga river and the Gomati river near his capital.[28] Following the decline of Tarumanagara, its territories, including the Jakarta area, became part of the Hindu Kingdom of Sunda. From the 7th to the early 13th century, the port of Sunda was under the Srivijaya maritime empire. According to the Chinese source, Chu-fan-chi, written circa 1225, Chou Ju-kua reported in the early 13th century that Srivijaya still ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula and western Java (Sunda). The source says the port of Sunda as strategic and thriving, mentioning pepper from Sunda as among the best in quality. The people worked in agriculture, and their houses were built on wooden piles.[29] The harbour area became known as Sunda Kelapa, (Sundanese: ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ ᮊᮨᮜᮕ) and by the 14th century, it was an important trading port for the Sunda kingdom.

The first European fleet, four Portuguese ships from Malacca, arrived in 1513 while looking for a route for spices.[30] The Sunda Kingdom made an alliance treaty with the Portuguese by allowing them to build a port in 1522 to defend against the rising power of Demak Sultanate from central Java.[31] In 1527, Fatahillah, a Javanese general from Demak attacked and conquered Sunda Kelapa, driving out the Portuguese. Sunda Kelapa was renamed Jayakarta[31] and became a fiefdom of the Banten Sultanate, which became a major Southeast Asian trading centre.

Through the relationship with Prince Jayawikarta of Banten Sultanate, Dutch ships arrived in 1596. In 1602, the British East India Company's first voyage, commanded by Sir James Lancaster, arrived in Aceh and sailed on to Banten where they were allowed to build a trading post. This site became the centre of British trade in the Indonesian archipelago until 1682.[32] Jayawikarta is thought to have made trading connections with the British merchants, rivals of the Dutch, by allowing them to build houses directly across from the Dutch buildings in 1615.[33]

Colonial era

When relations between Prince Jayawikarta and the Dutch deteriorated, his soldiers attacked the Dutch fortress. His army and the British, however, were defeated by the Dutch, in part owing to the timely arrival of Jan Pieterszoon Coen. The Dutch burned the British fort and forced them to retreat on their ships. The victory consolidated Dutch power, and they renamed the city Batavia in 1619.

Commercial opportunities in the city attracted native and especially Chinese and Arab immigrants. This sudden population increase created burdens on the city. Tensions grew as the colonial government tried to restrict Chinese migration through deportations. Following a revolt, 5,000 Chinese were massacred by the Dutch and natives on 9 October 1740, and the following year, Chinese inhabitants were moved to Glodok outside the city walls.[34] At the beginning of the 19th century, around 400 Arabs and Moors lived in Batavia, a number that changed little during the following decades. Among the commodities traded were fabrics, mainly imported cotton, batik and clothing worn by Arab communities.[35]

The city began to expand further south as epidemics in 1835 and 1870 forced residents to move away from the port. The Koningsplein, now Merdeka Square was completed in 1818, the housing park of Menteng was started in 1913,[36] and Kebayoran Baru was the last Dutch-built residential area.[34] By 1930, Batavia had more than 500,000 inhabitants,[37] including 37,067 Europeans.[38]

On 5 March 1942, the Japanese wrested Batavia from Dutch control, and the city was named Jakarta (Jakarta Special City (ジャカルタ特別市, Jakaruta tokubetsu-shi), under the special status that was assigned to the city). After the war, the Dutch name Batavia was internationally recognised until full Indonesian independence on 27 December 1949. The city, now renamed Jakarta, was officially proclaimed the national capital of Indonesia.

Independence era

After World War II ended, Indonesian nationalists declared independence on 17 August 1945,[39] and the government of the Jakarta City was changed into the Jakarta National Administration in the following month. During the Indonesian National Revolution, Indonesian Republicans withdrew from Allied-occupied Jakarta and established their capital in Yogyakarta.

After securing full independence, Jakarta again became the national capital in 1950.[34] With Jakarta selected to host the 1962 Asian Games, Sukarno, envisaging Jakarta as a great international city, instigated large government-funded projects with openly nationalistic and modernist architecture.[40][41] Projects included a cloverleaf interchange, a major boulevard (Jalan MH Thamrin-Sudirman), monuments such as The National Monument, Hotel Indonesia, a shopping centre, and a new building intended to be the headquarters of CONEFO. In October 1965, Jakarta was the site of an abortive coup attempt in which six top generals were killed, precipitating a violent anti-communist purge which killed at least 500,000 people, including some ethnic Chinese.[42] The event marked the beginning of Suharto's New Order. The first government was led by a mayor until the end of 1960 when the office was changed to that of a governor. The last mayor of Jakarta was Soediro until he was replaced by Soemarno Sosroatmodjo as governor. Based on law No. 5 of 1974 relating to regional governments, Jakarta was confirmed as the capital of Indonesia and one of the country's then 26 provinces.[43]

In 1966, Jakarta was declared a 'special capital region' (Daerah Khusus Ibukota), with a status equivalent to that of a province.[44] Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin served as governor from 1966 to 1977; he rehabilitated roads and bridges, encouraged the arts, built hospitals and a large number of schools. He cleared out slum dwellers for new development projects — some for the benefit of the Suharto family[45][46]— and attempted to eliminate rickshaws and ban street vendors. He began control of migration to the city to stem overcrowding and poverty.[47] Foreign investment contributed to a real estate boom that transformed the face of Jakarta.[48]

The boom ended with the 1997 Asian financial crisis, putting Jakarta at the centre of violence, protest and political manoeuvring. After three decades in power, support for President Suharto began to wane. Tensions peaked when four students were shot dead at Trisakti University by security forces. Four days of riots and violence ensued that killed an estimated 1,200, and destroyed or damaged 6,000 buildings, forcing Suharto to resign.[49] Much of the rioting targeted Chinese Indonesians.[50] In the post-Suharto era, Jakarta has remained the focal point of democratic change in Indonesia.[51] Jemaah Islamiah-connected bombings occurred almost annually in the city between 2000 and 2005,[34] with another in 2009.[52] In August 2007, Jakarta held its first-ever election to choose a governor as part of a nationwide decentralisation program that allows direct local elections in several areas.[53] Previously, governors were elected by the city's legislative body.

Government and politics

Jakarta is administratively equal to a province with special status. The executive branch is headed by an elected governor and a vice governor, while the Jakarta Regional People's Representative Council (Indonesian: Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Provinsi Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta, DPRD DKI Jakarta) is the legislative branch with 106 directly elected members. The Jakarta City Hall at the south of Merdeka Square houses the office of the governor and the vice governor, and serves the main administrative office.

Executive governance consists of five administrative cities (Indonesian: Kota Administrasi), each headed by a mayor and one administrative regency (Indonesian: Kabupaten Administrasi) headed by a regent (bupati). Unlike other cities and regencies in Indonesia where the mayor or regent are directly elected, Jakarta's mayors and regents are chosen by the governor. Each city and regency is divided into administrative districts.

Aside from representatives to the provincial parliament, Jakarta sends 21 delegates to the national lower house parliament. The representatives are elected from Jakarta's three national electoral districts, which also includes overseas voters.[54] It also sends 4 delegates, just like other provinces, to the national upper house parliament.

The Jakarta Smart City (JSC) program was launched on 14 December 2014 with a goal for smart governance, smart people, smart mobility, smart economy, smart living and a smart environment in the city using the web and various smartphone-based apps.[55]

The Greater Jakarta Metropolitan Regional Police maintains the law, security, and order of the Jakarta metropolitan area. It is led by a regional police chief (Indonesian: Kepala Kepolisian Daerah, Kapolda), who holds the rank of Inspector General of Police.

The Jayakarta Military Regional Command is the defense military command which serves the metropolitan area. It is led by a military regional commander (Indonesian: Panglima Daerah Militer, Pangdam), who holds the rank of Major General.

Municipal finances

The Jakarta provincial government relies on transfers from the central government for the bulk of its income. Local (non-central government) sources of revenue are incomes from various taxes such as vehicle ownership and vehicle transfer fees, among others.[56] The ability of the regional government to respond to Jakarta's many problems is constrained by limited finances.

The provincial government consistently runs a surplus of between 15–20% of planned spending, primarily because of delays in procurement and other inefficiencies.[57] Regular under-spending is a matter of public comment.[58] In 2013, the budget was around Rp 50 trillion ($US5.2 billion), equivalent to around $US380 per citizen. Spending priorities were on education, transport, flood control, environment and social spending (such as health and housing).[59] Jakarta's regional budget (APBD) was Rp 77.1 trillion ($US5.92 billion), Rp 83.2 trillion ($US6.2 billion), and Rp 89 trillion ($US6.35 billion) for the year of 2017, 2018 and 2019 respectively.[60][61][62]

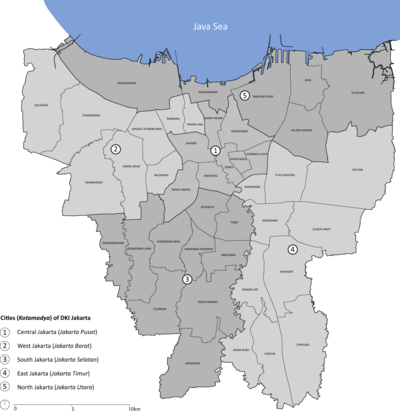

Administrative divisions

Jakarta consists of five Kota Administratif (Administrative cities/municipalities), each headed by a mayor, and one Kabupaten Administratif (Administrative regency). Each city and regency is divided into districts/Kecamatan. The administrative cities/municipalities of Jakarta are:

- Central Jakarta (Jakarta Pusat) is Jakarta's smallest city and the administrative and political centre. It is divided into eight districts. It is characterised by large parks and Dutch colonial buildings. Landmarks include the National Monument (Monas), Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta Cathedral and museums.[63]

- West Jakarta (Jakarta Barat) has the city's highest concentration of small-scale industries. It has eight districts. The area includes Jakarta's Chinatown and Dutch colonial landmarks such as the Chinese Langgam building and Toko Merah. It contains part of Jakarta Old Town.[64]

- South Jakarta (Jakarta Selatan), originally planned as a satellite city, is now the location of upscale shopping centres and affluent residential areas. It has ten districts and functions as Jakarta's groundwater buffer,[65] but recently the green belt areas are threatened by new developments. Much of the central business district is concentrated in Setiabudi, South Jakarta, bordering the Tanah Abang/Sudirman area of Central Jakarta.

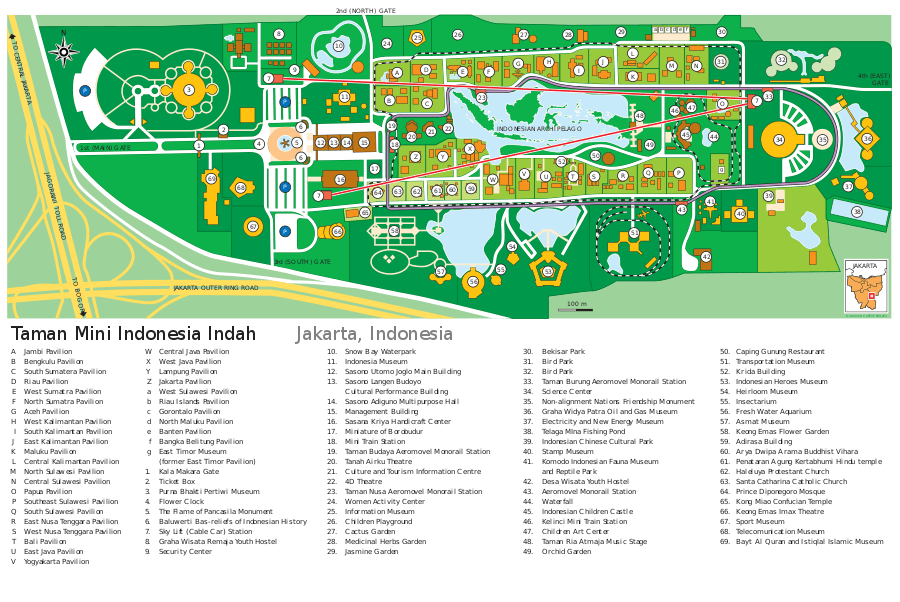

- East Jakarta (Jakarta Timur) territory is characterised by several industrial sectors.[66] Also located in East Jakarta are Taman Mini Indonesia Indah and Halim Perdanakusuma International Airport. This city has ten districts.

- North Jakarta (Jakarta Utara) is bounded by the Java Sea. It is the location of Port of Tanjung Priok. Large- and medium-scale industries are concentrated there. It contains part of Jakarta Old Town, which was the centre of VOC trade activity during the colonial era. Also located in North Jakarta is Ancol Dreamland (Taman Impian Jaya Ancol), the largest integrated tourism area in Southeast Asia.[67] North Jakarta is divided into six districts.

The only administrative regency (kabupaten) of Jakarta is the Thousand Islands (Kepulauan Seribu), formerly a district within North Jakarta. It is a collection of 105 small islands located on the Java Sea. It is of high conservation value because of its unique ecosystems. Marine tourism, such as diving, water bicycling, and windsurfing, are the primary tourist activities in this territory. The main mode of transportation between the islands is speed boats or small ferries.[68]

| City/regency | Area (km2) | Total population (2010 Census) | Total population (2014)[2] | Population density (per km2) in 2010 |

Population density (per km2) in 2014 |

HDI [69] 2015 estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Jakarta | 141.27 | 2,057,080 | 2,164,070 | 14,561 | 15,319 | 0.833 (Very High) |

| East Jakarta | 188.03 | 2,687,027 | 2,817,994 | 14,290 | 14,987 | 0.807 (Very High) |

| Central Jakarta | 48.13 | 898,883 | 910,381 | 18,676 | 18,915 | 0.796 (High) |

| West Jakarta | 129.54 | 2,278,825 | 2,430,410 | 17,592 | 18,762 | 0.797 (High) |

| North Jakarta | 146.66 | 1,645,312 | 1,729,444 | 11,219 | 11,792 | 0.796 (High) |

| Thousand Islands | 8.7 | 21,071 | 23,011 | 2,422 | 2,645 | 0.688 (Medium) |

Geography

Jakarta covers 699.5 square kilometres (270.1 sq mi), the smallest among any Indonesian provinces. However, its metropolitan area covers 6,392 square kilometres (2,468 sq mi), which extends into two of the bordering provinces of West Java and Banten.[70] The Greater Jakarta area includes three bordering regencies (Bekasi Regency, Tangerang Regency and Bogor Regency) and five adjacent cities (Bogor, Depok, Bekasi, Tangerang and South Tangerang).

Topography

Jakarta is situated on the northwest coast of Java, at the mouth of the Ciliwung River on Jakarta Bay, an inlet of the Java Sea. The northern part of Jakarta is plain land, some areas of which are below sea level[71] and subject to frequent flooding. The southern parts of the city are hilly. It is one of only two Asian capital cities located in the southern hemisphere (along with East Timor's Dili). Officially, the area of the Jakarta Special District is 662 km2 (256 sq mi) of land area and 6,977 km2 (2,694 sq mi) of sea area.[72] The Thousand Islands, which are administratively a part of Jakarta, are located in Jakarta Bay, north of the city.

Jakarta lies in a low and flat alluvial plain, ranging from −2 to 50 metres (−7 to 164 ft) with an average elevation of 8 metres (26 ft) above sea level with historically extensive swampy areas. Thirteen rivers flow through Jakarta. They are Ciliwung River, Kalibaru, Pesanggrahan, Cipinang, Angke River, Maja, Mookervart, Krukut, Buaran, West Tarum, Cakung, Petukangan, Sunter River and Grogol River.[73][74] They flow from the Puncak highlands to the south of the city, then across the city northwards towards the Java Sea. The Ciliwung River divides the city into the western and eastern districts.

These rivers, combined with the wet season rains and insufficient drainage due to clogging, make Jakarta prone to flooding. Moreover, Jakarta is sinking about 5 to 10 centimetres (2.0 to 3.9 inches) each year, and up to 20 centimetres (7.9 inches) in the northern coastal areas. After a feasibility study, a ring dyke is under construction around Jakarta Bay to help cope with the threat from the sea. The dyke will be equipped with a pumping system and retention areas to defend against seawater and function as a toll road. The project, known as Giant Sea Wall Jakarta, is expected to be completed by 2025.[75] In January 2014, the central government agreed to build two dams in Ciawi, Bogor and a 1.2-kilometre (0.75-mile) tunnel from Ciliwung River to Cisadane River to ease flooding in the city.[76] Nowadays, a 1.2-kilometre (0.75-mile), with capacity 60 cubic metres (2,100 cubic feet) per second, underground water tunnel between Ciliwung River and the East Flood Canal is being worked on to ease the Ciliwung River overflows.[77]

Climate

Jakarta has a tropical monsoon climate (Am) according to the Köppen climate classification system. The wet season in Jakarta covers the majority of the year, running from October through May. The remaining four months (June through September) constitute the city's drier season (each of these four months has an average monthly rainfall of fewer than 100 millimetres (3.9 in)). Technically speaking, however, only August qualifies as the genuine dry season month, as it has less than 60 millimetres (2.4 in) of rainfall. Located in the western part of Java, Jakarta's wet season rainfall peaks in January and February with average monthly rainfall of 299.7 millimetres (11.80 in), and its dry season's low point is in August with a monthly average of 43.2 mm (1.70 in).

| Climate data for Halim Perdanakusuma Airport, Jakarta, Indonesia (temperature: 1924–1994, precipitation: 1931–1994) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.3 (91.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.9 (84.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.1 (79.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20.6 (69.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 299.7 (11.80) |

299.7 (11.80) |

210.8 (8.30) |

147.3 (5.80) |

132.1 (5.20) |

96.5 (3.80) |

63.5 (2.50) |

43.2 (1.70) |

66.0 (2.60) |

111.8 (4.40) |

142.2 (5.60) |

203.2 (8.00) |

1,816 (71.5) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85 | 85 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 78 | 76 | 75 | 77 | 81 | 82 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 189 | 182 | 239 | 255 | 260 | 255 | 282 | 295 | 288 | 279 | 231 | 220 | 2,975 |

| Source 1: Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial[78] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (humidity and sun only)[79] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Jakarta | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.0) |

28.0 (82.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

29.0 (84.0) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ | 11+ | 10.8 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [80] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 1,452,000 | — |

| 1960 | 2,678,740 | +84.5% |

| 1970 | 3,915,406 | +46.2% |

| 1980 | 5,984,256 | +52.8% |

| 1990 | 8,174,756 | +36.6% |

| 2000 | 8,389,759 | +2.6% |

| 2010 | 9,625,579 | +14.7% |

| 2019 | 10,638,689 | +10.5% |

| source:[81] | ||

Jakarta attracts people from across Indonesia, often in search of employment. The 1961 census showed that 51% of the city's population was born in Jakarta.[82] Inward immigration tended to negate the effect of family planning programs.[43]

Between 1961 and 1980, the population of Jakarta doubled, and during the period 1980–1990, the city's population grew annually by 3.7%.[83] The 2010 census counted some 9.58 million people, well above government estimates.[84] The population rose from 4.5 million in 1970 to 9.5 million in 2010, counting only legal residents, while the population of Greater Jakarta rose from 8.2 million in 1970 to 28.5 million in 2010. As per 2014, the population of Jakarta stood at ten million,[85] with a population density of 15,174 people/km2.[86][87] As per 2014, the population of Greater Jakarta was 30 million, accounting for 11% of Indonesia's overall population.[88] It is predicted to reach 35.6 million people by 2030 to become the world's biggest megacity.[89] The gender ratio was 102.8 (males per 100 females) in 2010[90] and 101.3 in 2014.[91]

Ethnicity

Jakarta is a pluralistic and religiously diverse city. As of the 2010 Census, 36.17% of the city's population were Javanese, 28.29% Betawi, 14.61% Sundanese, 6.62% Chinese, 3.42% Batak, 2.85% Minangkabau, 0.96% Malays, Indo and others 7.08%.

The 'Betawi' (Orang Betawi, or 'people of Batavia') are the descendants of the people living in and around Batavia and became recognised as an ethnic group around the 18th–19th century. They mostly descend from Southeast Asian ethnic groups brought or attracted to Batavia to meet labour needs.[93][94] Betawi people are a creole ethnic group who came from various parts of Indonesia and intermarried with Chinese, Arabs and Europeans.[95] Betawi form a minority in the city; most lived in the fringe areas of Jakarta with hardly any Betawi-dominated regions of central Jakarta.[96]

A significant Chinese community has lived in Jakarta for many centuries. They traditionally reside around old urban areas, such as Pinangsia, Pluit and Glodok (Jakarta Chinatown) areas. They also can be found in the old Chinatowns of Senen and Jatinegara. Officially, they make up 5.53% of the Jakarta population, although this number may be under-reported.[97]

The Sumatran residents are diverse. According to the 2010 Census, roughly 346,000 Batak, 305,000 Minangkabau and 155,000 Malays lived in the city. The number of Batak people has grown in ranking, from eighth in 1930 to fifth in 2000. Toba Batak is the largest sub-ethnic Batak group in Jakarta.[98] Minangkabau people generally work as merchants, peddlers, and artisans, with more in white-collar professions, such as doctors, teachers and journalists.[99][100]

Language

Indonesian is the official and dominant language of Jakarta, while many elderly people speak Dutch or Chinese, depending on their upbringing. English is also widely used for communication, especially in Central and South Jakarta.[101] Each of the ethnic groups uses their mother language at home, such as Betawi, Javanese, and Sundanese. The Betawi language is distinct from those of the Sundanese or Javanese, forming itself as a language island in the surrounding area. It is mostly based on the East Malay dialect and enriched by loan words from Dutch, Portuguese, Sundanese, Javanese, Minangkabau, Chinese, and Arabic.

Religion

In 2017, Jakarta's religious composition was distributed over Islam (83.43%), Protestantism (8.63%), Catholicism (4.0%), Buddhism (3.74%), Hinduism (0.19%), and Confucianism (0.01%). About 231 people claimed to follow folk religions.[102]

Most pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) in Jakarta are affiliated with the traditionalist Nahdlatul Ulama,[103] modernist organisations mostly catering to a socioeconomic class of educated urban elites and merchant traders. They give priority to education, social welfare programs and religious propagation.[104] Many Islamic organisations have headquarters in Jakarta, including Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesian Ulema Council, Muhammadiyah, Jaringan Islam Liberal, and Front Pembela Islam.

The Roman Catholic community has a Metropolis, the Archdiocese of Jakarta that includes West Java as part of the ecclesiastical province. There is also a Bahá'í community.[105]

Istiqlal Mosque, the largest mosque in Southeast Asia

Istiqlal Mosque, the largest mosque in Southeast Asia The Jakarta Cathedral, one of the oldest churches in Jakarta

The Jakarta Cathedral, one of the oldest churches in Jakarta Kim Tek Ie, the oldest Taoist and Buddhist temple in Jakarta

Kim Tek Ie, the oldest Taoist and Buddhist temple in Jakarta Aditya Jaya Hindu temple, Rawamangun, East Jakarta

Aditya Jaya Hindu temple, Rawamangun, East Jakarta- Sikh Gurdwara in Pasar Baru, Jakarta

Culture

As the capital of Indonesia, Jakarta is the melting point of cultures of all ethnic groups of the country. Though Betawi people are considered as an indigenous community of Jakarta, the culture of the city represents many languages and ethnic groups, support differences in regard to religion, traditions and linguistics, rather than any single and dominant culture.

Arts and festivals

The Betawi culture is distinct from those of the Sundanese or Javanese, forming a language island in the surrounding area. Betawi arts have a low profile in Jakarta, and most Betawi people have moved to the suburbs. The cultures of the Javanese and other Indonesian ethnic groups have a higher profile than that of the Betawi. There is a significant Chinese influence in Betawi culture, reflected in the popularity of Chinese cakes and sweets, firecrackers and Betawi wedding attire that demonstrates Chinese and Arab influences.

Some festivals such as the Jalan Jaksa Festival, Kemang Festival, Festival Condet and Lebaran Betawi include efforts to preserve Betawi arts by inviting artists to display performances.[106][107][108] Jakarta has several performing art centres, such as the classical concert hall Aula Simfonia Jakarta in Kemayoran, Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) art centre in Cikini, Gedung Kesenian Jakarta near Pasar Baru, Balai Sarbini in the Plaza Semanggi area, Bentara Budaya Jakarta in the Palmerah area, Pasar Seni (Art Market) in Ancol, and traditional Indonesian art performances at the pavilions of some provinces in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. Traditional music is often found at high-class hotels, including Wayang and Gamelan performances. Javanese Wayang Orang performances can be found at Wayang Orang Bharata theatre.

Arts and culture festivals and exhibitions include the annual ARKIPEL – Jakarta International Documentary and Experimental Film Festival, Jakarta International Film Festival (JiFFest), Djakarta Warehouse Project, Jakarta Fashion Week, Jakarta Fashion & Food Festival (JFFF), Jakarnaval, Jakarta Night Festival, Kota Tua Creative Festival, Indonesia International Book Fair (IIBF), Indonesia Creative Products and Jakarta Arts and Crafts exhibition. Art Jakarta is a contemporary art fair, which is held annually. Flona Jakarta is a flora-and-fauna exhibition, held annually in August at Lapangan Banteng Park, featuring flowers, plant nurseries, and pets. Jakarta Fair is held annually from mid-June to mid-July to celebrate the anniversary of the city and is mostly centred around a trade fair. However, this month-long fair also features entertainment, including arts and music performances by local musicians. Jakarta International Java Jazz Festival (JJF) is one of the largest jazz festivals in the world and arguably the biggest in the Southern hemisphere, and is held annually in March.

Several foreign art and culture centres in Jakarta promote culture and language through learning centres, libraries and art galleries. These include the Chinese Confucius Institute, the Dutch Erasmus Huis, the British Council, the French Alliance Française, the German Goethe-Institut, the Japan Foundation, and the Jawaharlal Nehru Indian Cultural Center.

Cuisine

All varieties of Indonesian cuisine have a presence in Jakarta. The local cuisine is Betawi cuisine, which reflects various foreign culinary traditions. Betawi cuisine is heavily influenced by Malay-Chinese Peranakan cuisine, Sundanese and Javanese cuisine, which is also influenced by Indian, Arabic and European cuisines. One of the most popular local dishes of Betawi cuisine is Soto Betawi which is prepared from chunks of beef and offal in rich and spicy cow's milk or coconut milk broth. Other popular Betawi dishes include soto kaki, nasi uduk, kerak telor (spicy omelette), nasi ulam, asinan, ketoprak, rujak and gado-gado Betawi (salad in peanut sauce).

Jakarta cuisine can be found in modest street-side warung food stalls and kaki lima (five legs) travelling vendors to high-end fine dining restaurants.[109] Live music venues and exclusive restaurants are abundant.[110] Many traditional foods from far-flung regions in Indonesia can be found in Jakarta. For example, traditional Padang restaurants and low-budget Warteg (Warung Tegal) food-stalls are ubiquitous in the capital. Other popular street foods include nasi goreng (fried rice), sate (skewered meats), pecel lele (fried catfish), bakso (meatballs), bakpau (Chinese bun) and siomay (fish dumplings).

Jalan Sabang,[111][112] Jalan Sidoarjo, Jalan Kendal at Menteng area, Kota Tua, Blok S, Blok M,[113] Jalan Tebet[114] are all popular destinations for street-food lovers. Trendy restaurants, cafe and bars can be found at Menteng, Kemang,[115] Jalan Senopati,[116] Kuningan, Senayan, Pantai Indah Kapuk,[117] and Kelapa Gading. Chinese street-food is plentiful at Jalan Pangeran, Manga Besar and Petak Sembilan in the old Jakarta area, while the Little Tokyo area of Blok M has many Japanese style restaurants and bars.[118] Lenggang Jakarta is a food court, accommodating small traders and street vendors,[119] where Indonesian foods are available within a single compound. At present, there are two such food courts, located at Monas and Kemayoran.[120] Thamrin 10 is a food and creative park located at Menteng, where varieties of food stall are available.[121]

Global fast-food chains like McDonald's, KFC, Burger King, Carl's Jr., Wendy's, A&W, Fatburger, Johnny Rockets, Starbucks, Dunkin' Donuts are present, along with local brands like J'CO, Es Teler 77, Kebab Turki, CFC, and Japanese HokBen.[122] Foreign cuisines such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Indian, American, French, Mediterranean cuisine's like Turkish, Italian, Middle-Eastern cuisine, and modern fusion food restaurants can all be found in Jakarta.

Museums

Jakarta hosts 142 museums,[123] clustered around the Central Jakarta's Merdeka Square area, Jakarta Old Town and Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. The Old Town contains museums in former institutional buildings of colonial Batavia, including Jakarta History Museum (former City Hall of Batavia), Wayang Museum (Puppet Museum) (former Church of Batavia), the Fine Art and Ceramic Museum (former Court House of Justice of Batavia), the Maritime Museum (former Sunda Kelapa warehouse), Bank Indonesia Museum (former Javasche Bank) and Bank Mandiri Museum (former Nederlandsche Handels Maatschappij).

Museums clustered in central Jakarta around the Merdeka Square area include National Museum of Indonesia which also known as Gedung Gajah (the Elephant Building), National Gallery of Indonesia, National History Museum at National Monument, Istiqlal Islamic Museum in Istiqlal Mosque and Jakarta Cathedral Museum on the second floor of Jakarta Cathedral. Also in central is the Taman Prasasti Museum (the former cemetery of Batavia), and Textile Museum in Tanah Abang area. Museum MACAN is an art museum of modern and contemporary Indonesian and international art located at West Jakarta.[124]

The recreational area of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah in East Jakarta contains fourteen museums, such as Indonesia Museum, Purna Bhakti Pertiwi Museum, Asmat Museum, Bayt al-Qur'an Islamic Museum, Pusaka (heirloom) Museum, and other science-based museums such as Research & Technology Information Center, Komodo Indonesian Fauna Museum, Insect Museum, Petrol and Gas Museum, plus the Transportation Museum. Other museums include Satria Mandala Military Museum, Museum Sumpah Pemuda, and Lubang Buaya.

Media

Daily newspapers include Kompas, Koran Tempo, Media Indonesia, and Republika. English-language newspapers are also published daily, for example, The Jakarta Post and The Jakarta Globe. Chinese language newspapers also circulate, such as Indonesia Shang Bao (印尼商报), Harian Indonesia (印尼星洲日报), and Guo Ji Ri Bao (国际日报). The only Japanese language newspaper is The Daily Jakarta Shimbun (じゃかるた新聞). Jakarta also has the daily newspapers segment such as Pos Kota, Warta Kota, Koran Jakarta, Berita Kota for local readers; Bisnis Indonesia, Investor Daily, Kontan, Harian Neraca (business news) as well as Top Skor and Soccer (sports news).

Jakarta is the headquarters for Indonesia's state media, TVRI as well as private national television networks, such as Metro TV, tvOne, Kompas TV, RCTI and NET. Jakarta has local television channels such as Jak TV, O Channel, Elshinta TV, and DAAI TV Indonesia. The city is home to the country's leading pay television service. Cable channels available includes First Media and TelkomVision. Satellite television (DTH) has yet to gain mass acceptance in Jakarta. Prominent DTH entertainment services are Indovision, Okevision, Yes TV, Transvision, and Aora TV. Many TV stations are analogue PAL, but some are now converting to digital signals using DVB-T2 following a government plan to digital television migration.[125]

Around 75 radio stations broadcast in Jakarta, 52 on the FM band, and 23 on the AM band.

Economy

Indonesia is the largest economy of ASEAN, and Jakarta is the economic nerve centre of the Indonesian archipelago. Jakarta's nominal GDP was US$483.8 billion in 2016, which is about 17.5% of Indonesia's.[126] Jakarta ranked at 21 in the list of Cities Of Economic Influence Index in 2020 by CEOWORLD magazine.[127] According to the Japan Center for Economic Research, GRP per capita of Jakarta will rank 28th among the 77 cities in 2030 from 41st in 2015, the largest in Southeast Asia.[128] Savills Resilient Cities Index has predicted Jakarta to be within the top 20 cities in the world by 2028.[129][130]

Jakarta's economy depends highly on manufacturing and service sectors such as banking, trading and financial. Industries include electronics, automotive, chemicals, mechanical engineering and biomedical sciences. The head office of Bank Indonesia and Indonesia Stock Exchange are located in the city. Most of the SOEs include Pertamina, PLN, Angkasa Pura, and Telkomsel operate head offices in the city, as do major Indonesian conglomerates, such as Salim Group, Sinar Mas Group, Astra International, Gudang Garam, Kompas-Gramedia, and MNC Group. The headquarters of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Indonesian Employers Association are also located in the city. As of 2017, the city is home to six Forbes Global 2000, two Fortune 500 and four Unicorn companies.[131][132][133] Google and Alibaba has regional cloud centers in Jakarta.[134]

.jpg)

As of 2018, Jakarta contributes about 17% of Indonesia's GRDP (Gross Regional Domestic Product).[135] In 2017, the economic growth was 6.22%.[136] Throughout the same year, the total value of investment was Rp 108.6 trillion (US$8 billion), an increase of 84.7% from the previous year.[137] In 2015, GDP per capita was estimated at Rp 194.87 million (US$14,570).[138] The most significant contributions to GRDP were by finance, ownership and business services (29%); trade, hotel and restaurant sector (20%), and manufacturing industry sector (16%).[43] In 2007, the increase in per capita GRDP of Jakarta inhabitants was 11.6% compared to the previous year.[43] Both GRDP by at current market price and GRDP by at 2000 constant price in 2007 for the Municipality of Central Jakarta, which was Rp 146 million and Rp 81 million, was higher than other municipalities in Jakarta.[43]

The Wealth Report 2015 by Knight Frank reported that 24 individuals in Indonesia in 2014 had wealth at least US$1 billion and 18 live in Jakarta.[139] The cost of living continues to rise. Both land price and rents have become expensive. Mercer's 2017 Cost of Living Survey ranked Jakarta as 88th costliest city in the world for expatriates.[140] Industrial development and the construction of new housing thrive on the outskirts, while commerce and banking remain concentrated in the city centre.[141] Jakarta has a bustling luxury property market. Knight Frank, a global real estate consultancy based in London, reported in 2014 that Jakarta offered the highest return on high-end property investment in the world in 2013, citing a supply shortage and a sharply depreciated currency as reasons.[142]

Shopping

As of 2015, with a total of 550 hectares, Jakarta had the largest shopping mall floor area within a single city.[143][144] Malls include Plaza Indonesia, Grand Indonesia, Plaza Senayan, Senayan City, Pacific Place, Mall Taman Anggrek, and Pondok Indah Mall.[145] Fashion retail brands in Jakarta include Debenhams, in Senayan City and Lippo Mall Kemang Village,[146] Japanese Sogo,[147] Seibu in Grand Indonesia Shopping Town, and French brand, Galeries Lafayette, at Pacific Place. The new Satrio-Casablanca shopping belt includes centres such as Kuningan City, Mal Ambassador, Kota Kasablanka, and Lotte Shopping Avenue.[148] Shopping malls are also located at Grogol and Puri Indah in West Jakarta.

Traditional markets include Blok M, Pasar Mayestik, Tanah Abang, Senen, Pasar Baru, Glodok, Mangga Dua, Cempaka Mas, and Jatinegara. Special markets sell antique goods at Surabaya Street and gemstones in Rawabening Market.[149]

Tourism

Though Jakarta has been named the most popular location as per tag stories[150] and ranked eighth most-posted among the cities in the world in 2017 on image-sharing site Instagram,[151] it is not a top international tourist destination. The city, however, is ranked as the fifth fastest-growing tourist destination among 132 cities according to MasterCard Global Destination Cities Index.[152] The World Travel and Tourism Council also listed Jakarta as among the top ten fastest-growing tourism cities in the world in 2017[153] and categorised it as an emerging performer, which will see a significant increase in tourist arrivals in less than ten years.[154] According to Euromonitor International's latest Top 100 City Destinations Ranking of 2019, Jakarta ranked at 57th among 100 most visited cities of the world.[155]

Most of the visitors attracted to Jakarta are domestic tourists. As the gateway of Indonesia, Jakarta often serves as a stop-over for foreign visitors on their way to other Indonesian tourist destinations such as Bali, Lombok, Komodo Island and Yogyakarta. Jakarta is trying to attract more international tourist by MICE tourism, by arranging increasing numbers of conventions.[156][157] In 2012, the tourism sector contributed Rp. 2.6 trillion (US$268.5 million) to the city's total direct income of Rp. 17.83 trillion (US$1.45 billion), a 17.9% increase from the previous year 2011.

The popular heritage tourism attractions are in Kota[158] and around Merdeka square. Kota is the centre of old Jakarta, with its Maritime Museum, Kota Intan Bridge, Gereja Sion, Wayang Museum, Stadhuis Batavia, Fine Art and Ceramic Museum, Toko Merah, Bank Indonesia Museum, Bank Mandiri Museum, Jakarta Kota railway station, and Glodok (Chinatown).[159] Kota Tua was named the most-visited destination in Indonesia in 2017 by Instagram.[160] In the old ports of Sunda Kelapa, the tall-masted pinisi ships are still anchored.

Other tourist attractions include the Thousand Islands, Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Setu Babakan, Ragunan Zoo, Sunda Kelapa old port and the Ancol Dreamland complex on Jakarta Bay, which houses Dunia Fantasi (Fantasy World) theme park, Sea World, Atlantis Water Adventure, and Gelanggang Samudra. Thousand Islands, which is north to the coast of the city and in the Java Sea is also a popular tourist destination.

Most international hotel chains have a presence in the city. Jalan Jaksa and surrounding areas are popular among backpackers for cheaper accommodation, travel agencies, second-hand bookstores, money changers, laundries and pubs.[161] PIK is a relatively new suburb for hangout,[162] while Kemang is a popular suburb for expats.

Infrastructure

To transform the city into a more livable one, a 10-year "urban regeneration" project was undertaken, at a cost of Rp 571 trillion ($40.5 billion). The project aimed to develop infrastructure, including the creation of a better integrated public transit system and the improvement of the city's clean water and wastewater systems, housing and flood control systems.[163]

Water supply

Two private companies, PALYJA and Aetra, provide piped water in the western and eastern half of Jakarta respectively under 25-year concession contracts signed in 1998. A public asset holding company called PAM Jaya owns the infrastructure. Eighty per cent of the water distributed in Jakarta comes through the West Tarum Canal system from Jatiluhur reservoir on the Citarum River, 70 km (43 mi) southeast of the city. The water supply was privatised by President Suharto in 1998 to the French company Suez Environnement and the British company Thames Water International. Both companies subsequently sold their concessions to Indonesian companies. Customer growth in the first seven years of the concessions had been lower than before, possibly because of substantial inflation-adjusted tariff increases during this period. In 2005, tariffs were frozen, leading the private water companies to cut down on investments.

According to PALYJA, the service coverage ratio increased substantially from 34% (1998) to 65% (2010) in its western half of the concession.[164] According to data by the Jakarta Water Supply Regulatory Body, access in the eastern half of the city served by PTJ increased from about 57% in 1998 to about 67% in 2004 but stagnated afterwards.[165] However, other sources cite much lower access figures for piped water supply to houses, excluding access provided through public hydrants: one study estimated access as low as 25% in 2005,[166] while another estimated it to be as low as 18.5% in 2011.[167] Those without access to piped water get water mostly from wells that are often salty and unsanitary. As of 2017, according to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, Jakarta had a crisis over clean water.[168]

Healthcare

Jakarta has many of the country's best-equipped private and public healthcare facilities. In January 2014, the Indonesian government launched a universal health care system called the Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN). Covering around 250 million people, it is the world's most extensive insurance system.[169] It is expected that the entire population will be covered in 2019.[170][171][172]

Government run hospitals are of a good standard but are often overcrowded. Government-run specialised hospitals include Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Gatot Soebroto Army Hospital, as well as community hospitals and puskesmas. Other options for healthcare services include private hospitals and clinics. The private healthcare sector has seen significant changes, as the government began allowing foreign investment in the private sector in 2010. While some private facilities are run by nonprofit or religious organisations, most are for-profit. Hospital chains such as Siloam, Mayapada, Mitra Keluarga, Medika, Medistra, Ciputra, and Hermina operate in the city.[173][174]

Transport

As a metropolitan area of about 30 million people, Jakarta has a variety of transport systems.[175]

The city prioritised development of road networks, which were mostly designed to accommodate private vehicles.[176] A notable feature of Jakarta's present road system is the toll road network. Composed of an inner and outer ring road and five toll roads radiating outwards, the network provides inner as well as outer city connections. An 'odd-even' policy limits road use to cars with either odd or even-numbered registration plates on a particular day as a transitional measure to alleviate traffic congestion until the future introduction of electronic road pricing.

There are many bus terminals in the city, from where buses operate on numerous routes to connect neighborhoods within the city limit, to other areas of Greater Jakarta area and to cities across the island of Java. The biggest of the bus terminal is Pulo Gebang Bus Terminal, which is arguably the largest of its kind in Southeast Asia.[177] Main terminus for long distance train services are Gambir and Pasar Senen. High-speed railways being constructed connecting Jakarta to Bandung and another one is at planning stage from Jakarta to Surabaya.

Rapid transit in Greater Jakarta consists of TransJakarta bus rapid transit, Jakarta LRT, Jakarta MRT, KRL Commuterline commuter rail, and Soekarno-Hatta Airport Rail Link. Another transit system Greater Jakarta LRT is expected to be operational by early 2021.

Privately owned bus systems like Kopaja, MetroMini, Mayasari Bakti and PPD also provide important services for Jakarta commuters with numerous routes throughout the city. Pedicabs are banned from the city for causing traffic congestion. Bajaj auto rickshaw provide local transportation in the back streets of some parts of the city. Angkot microbuses also play a major role in road transport of Jakarta. Taxicabs and ojeks (motorcycle taxis) are available in the city.

Soekarno–Hatta International Airport (CGK) is the main airport serving the Greater Jakarta area, while Halim Perdanakusuma Airport (HLP) accommodates private and low-cost domestic flights. Other airports in the Jakarta metropolitan area include Pondok Cabe Airport and an airfield on Pulau Panjang, part of the Thousand Island archipelago.

Indonesia's busiest and Jakarta's main seaport Tanjung Priok serves many ferry connections to different parts of Indonesia.The old port Sunda Kelapa only accommodate pinisi, a traditional two masted wooden sailing ship serving inter-island freight service in the archipelago. Muara Angke Port was renovated, which is used as a public port to Thousand Islands (Indonesia), while Marina Ancol Port ia used as a tourist port.[178]Cityscape

Architecture

Jakarta has architecturally significant buildings spanning distinct historical and cultural periods. Architectural styles reflect Malay, Javanese, Arabic, Chinese and Dutch influences.[179] External influences inform the architecture of the Betawi house. The houses were built of nangka wood (Artocarpus integrifolia) and comprise three rooms. The shape of the roof is reminiscent of the traditional Javanese joglo.[35] Additionally, the number of registered cultural heritage buildings has increased.[180]

Colonial buildings and structures include those that were constructed during the colonial period. The dominant colonial styles can be divided into three periods: the Dutch Golden Age (17th to late 18th century), the transitional style period (late 18th century – 19th century), and Dutch modernism (20th century). Colonial architecture is apparent in houses and villas, churches, civic buildings and offices, mostly concentrated in the Jakarta Old Town and Central Jakarta. Architects such as J.C. Schultze and Eduard Cuypers designed some of the significant buildings. Schultze's works include Jakarta Art Building, the Indonesia Supreme Court Building and Ministry of Finance Building, while Cuypers designed Bank Indonesia Museum and Bank Mandiri Museum.

In the early 20th century, most buildings were built in Neo-Renaissance style. By the 1920s, the architectural taste had begun to shift in favour of rationalism and modernism, particularly art deco architecture. The elite suburb Menteng, developed during the 1910s, was the city's first attempt at creating an ideal and healthy housing for the middle class. The original houses had a longitudinal organisation, with overhanging eaves, large windows and open ventilation, all practical features for a tropical climate.[181] These houses were developed by N.V. de Bouwploeg, and established by P.A.J. Moojen.

After independence, the process of nation-building in Indonesia and demolishing the memory of colonialism was as important as the symbolic building of arterial roads, monuments, and government buildings. The National Monument in Jakarta, designed by Sukarno, is Indonesia's beacon of nationalism. In the early 1960s, Jakarta provided highways and super-scale cultural monuments as well as Senayan Sports Stadium. The parliament building features a hyperbolic roof reminiscent of German rationalist and Corbusian design concepts.[182] The office tower Wisma 46 soars to a height of 262 metres (860 feet) with 48 stories and its nib-shaped top celebrates technology and symbolises stereoscopy.

The urban construction booms continued in the 21st century. The Golden Triangle of Jakarta is one of the fastest evolving CBD's in the Asia-Pacific region.[183] According to CTBUH and Emporis, there are 88 skyscrapers that reach or exceed 150 metres (490 feet), which puts the city in the top 10 of world rankings.[184] It has more buildings taller than 150 metres than any other Southeast Asian or Southern Hemisphere cities.

Landmarks

Most landmarks, monuments and statues in Jakarta were begun in the 1960s during the Sukarno era, then completed in the Suharto era, while some date from the colonial period. Although many of the projects were completed after his presidency, Sukarno, who was an architect, is credited for planning Jakarta's monuments and landmarks, as he desired the city to be the beacon of a powerful new nation. Among the monumental projects were built, initiated, and planned during his administration are the National Monument, Istiqlal mosque, the Legislature Building, and the Gelora Bung Karno stadium. Sukarno also built many nationalistic monuments and statues in the capital city.[185]

The most famous landmark, which became the symbol of the city, is the 132-metre-tall (433-foot) obelisk of the National Monument (Monumen Nasional or Monas) in the centre of Merdeka Square. On its southwest corner stands a Mahabharata-themed Arjuna Wijaya chariot statue and fountain. Further south through Jalan M.H. Thamrin, one of the main avenues, the Selamat Datang monument stands on the fountain in the centre of the Hotel Indonesia roundabout. Other landmarks include the Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta Cathedral and the Immanuel Church. The former Batavia Stadhuis, Sunda Kelapa port in Jakarta Old Town is another landmark. The Gama Tower building in South Jakarta, at 310 metres, is the tallest building in Indonesia.

Some of statues and monuments are nationalist, such as the West Irian Liberation Monument, the Tugu Tani, the Youth statue and the Dirgantara statue. Some statues commemorate Indonesian national heroes, such as the Diponegoro and Kartini statues in Merdeka Square. The Sudirman and Thamrin statues are located on the streets bearing their names. There is also a statue of Sukarno and Hatta at the Proclamation Monument at the entrance to Soekarno–Hatta International Airport.

Parks and lakes

In June 2011, Jakarta had only 10.5% green open spaces (Ruang Terbuka Hijau) although this grew to 13.94%. Public parks are included in public green open spaces.[186] There are about 300 integrated child-friendly public spaces (RPTRA) in the city in 2019.[187] As of 2014, 183 water reservoirs and lakes supported the greater Jakarta area.[188]

- Merdeka Square (Medan Merdeka) is an almost 1 km2 field housing the symbol of Jakarta, Monas or Monumen Nasional (National Monument). Until 2000, it was the world's largest city square. The square was created by Dutch Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels (1810) and was originally named Koningsplein (King's Square). On 10 January 1993, President Soeharto started the beautification of the square. Features including a deer park and 33 trees that represent the 33 provinces of Indonesia.[189]

- Lapangan Banteng (Buffalo Field) is located in Central Jakarta near Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta Cathedral, and Jakarta Central Post Office. It covers about 4.5 hectares. Initially, it was called Waterlooplein and functioned as the ceremonial square during the colonial period. Colonial monuments and memorials erected on the square during the colonial period were demolished during the Sukarno era. The most notable monument in the square is the Monumen Pembebasan Irian Barat (Monument of the Liberation of West Irian). During the 1970s and 1980s, the park was used as a bus terminal. In 1993, the park was again turned into a public space. It became a recreation place for people and now serves as an exhibition place or for other events.[190] 'Jakarta Flona' (Flora dan Fauna), a flower and decoration plants and pet exhibition, is held in this park around August annually.

- Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (Miniature Park of Indonesia), in East Jakarta, has ten mini parks.

- Suropati Park is located in Menteng, Central Jakarta. The park is surrounded by Dutch colonial buildings. Taman Suropati was known as Burgemeester Bisschopplein during the colonial time. The park is circular-shaped with a surface area of 16,322 square metres (175,690 square feet). Several modern statues were made for the park by artists of ASEAN countries, which contributes to its nickname Taman persahabatan seniman ASEAN ('Park of the ASEAN artists friendship').[191]

- Menteng Park was built on the site of the former Persija football stadium. Situ Lembang Park is also located nearby, which has a lake at the centre.

- Kalijodo Park is the newest park, in Penjaringan subdistrict, with 3.4 hectares (8.4 acres) beside the Krendang River. It formally opened on 22 February 2017. The park is open 24 hours as green open space (RTH) and child-friendly integrated public space (RPTRA) and has international-standard skateboard facilities.[192]

- Muara Angke Wildlife Sanctuary and Angke Kapuk Nature Tourism Park at Penjaringan in North Jakarta.[193]

- Ragunan Zoo is located in Pasar Minggu, South Jakarta. It is the world's third-oldest zoo and is the second-largest with the most diverse animal and plant populations.[194]

- Setu Babakan is a 32-hectare lake surrounded by Betawi cultural village, located at Jagakarsa, South Jakarta.[195] Dadap Merah Park is also found in this area.

- Ancol Dreamland is the largest integrated tourism area in Southeast Asia. It is located along the bay, at Ancol in North Jakarta.

- Taman Waduk Pluit/Pluit Lake park and Putra Putri Park at Pluit, North Jakarta.[196]

- Tebet Honda Park, Puring Park, Mataram Park, Taman Langsat and Taman Ayodya in South Jakarta[197][198]

Sports

Jakarta hosted the 1962 Asian Games[199] and the 2018 Asian Games, co-hosted by Palembang.[200] Jakarta also hosted the Southeast Asian Games in 1979, 1987, 1997 and 2011 (supporting Palembang). Gelora Bung Karno Stadium, the biggest in the city with a capacity of 77,193 seats,[201] hosted the group stage, quarterfinal and final of the 2007 AFC Asian Cup along with Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam.[202][203]

The Senayan sports complex has several sports venues, including the Bung Karno football stadium, Madya Stadium, Istora Senayan, aquatic arena, baseball field, basketball hall, a shooting range, several indoor and outdoor tennis courts. The Senayan complex was built in 1960 to accommodate the 1962 Asian Games. For basketball, the Kelapa Gading Sport Mall in Kelapa Gading, North Jakarta, with a capacity of 7,000 seats, is the home arena of the Indonesian national basketball team. The BritAma Arena serves as a playground for Satria Muda Pertamina Jakarta, the 2017 runner-up of the Indonesian Basketball League. Jakarta International Velodrome is a sporting facility located at Rawamangun, which was used as a venue for the 2018 Asian Games. It has a seating capacity of 3,500 for track cycling, and up to 8,500 for shows and concerts,[204] which can also be used for various sports activities such as volleyball, badminton and futsal. Jakarta International Equestrian Park is an equestrian sports venue located at Pulomas, which was also used as a venue for 2018 Asian Games.[205]

The Jakarta Car-Free Days are held weekly on Sunday on the main avenues of the city, Jalan Sudirman, and Jalan Thamrin, from 6 AM to 11 AM. The briefer Car-Free Day, which lasts from 6 AM to 9 AM, is held on every other Sunday. The event invites local pedestrians to do sports and exercise and have their activities on the streets that are usually full of traffic. Along the road from the Senayan traffic circle on Jalan Sudirman, South Jakarta, to the "Selamat Datang" Monument at the Hotel Indonesia traffic circle on Jalan Thamrin, north to the National Monument in Central Jakarta, cars are blocked from entering. During the event, morning gymnastics, callisthenics and aerobic exercises, futsal games, jogging, bicycling, skateboarding, badminton, karate, on-street library and musical performances take over the roads and the main parks.[206]

Jakarta's most popular home football club is Persija, which plays in Indonesia Super League and uses Bung Karno Stadium as a home venue. Another football team in Jakarta is Persitara who compete in 2nd Division Football League and play in Kamal Muara Stadium and Soemantri Brodjonegoro Stadium.

Jakarta Marathon is said to be the "biggest running event of Indonesia". It is recognised by AIMS and IAAF. It was established in 2013 to promote Jakarta sports tourism. In the 2015 edition, more than 15,000 runners from 53 countries participated.[207][208][209][210][211]

Education

Jakarta is home to colleges and universities. The University of Indonesia (UI) is the largest and oldest tertiary-level educational institution in Indonesia. It is a public institution with campuses in Salemba (Central Jakarta) and in Depok.[212] The three other public universities in Jakarta are Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, the State University of Jakarta (UNJ)[213] and the University of Pembangunan Nasional 'Veteran' Jakarta (UPN "Veteran" Jakarta).[214] Some major private universities in Jakarta are Trisakti University, The Christian University of Indonesia, Mercu Buana University, Tarumanagara University, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia, Pelita Harapan University, Bina Nusantara University,[215] Jayabaya University,[216] and Pancasila University.[217]

STOVIA (School tot Opleiding van Indische Artsen) was the first high school in Jakarta, established in 1851.[218] Jakarta houses many students from around Indonesia, many of whom reside in dormitories or home-stay residences. For basic education, a variety of primary and secondary schools are available, tagged with the public (national), private (national and bi-lingual national plus) and international labels. Four of the major international schools are the Gandhi Memorial International School, IPEKA International Christian School[219] Jakarta Intercultural School and the British School Jakarta. Other international schools include the Jakarta International Korean School, Bina Bangsa School, Jakarta International Multicultural School,[220] Australian International School,[221] New Zealand International School,[222] Singapore International School and Sekolah Pelita Harapan.[223]

International relations

Jakarta hosts foreign embassies. Jakarta also serves as the seat of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Secretariat and is ASEAN's diplomatic capital.[224]

Jakarta is a member of the Asian Network of Major Cities 21, C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and ASEAN Smart Cities Network.

Sister cities

Jakarta signed sister city agreements with other cities, including Casablanca. To promote friendship between two cities, the main avenue famous for its shopping and business centres was named after Jakarta's Moroccan sister city. No street in Casablanca is named after Jakarta. However, the Moroccan capital city of Rabat has an avenue named after Sukarno, Indonesia's first president, to commemorate his visit in 1960 and as a token of friendship.[225]

Jakarta has established a partnership with Rotterdam, especially on integrated urban water management, including capacity-building and knowledge exchange.[226] This cooperation is mainly because both cities are dealing with similar problems; they lie in low-lying flat plains and are prone to flooding. Additionally, for below-sea-level areas, they have both implemented drainage systems involving canals, dams, and pumps vital for both cities.

|

|

|

|

See also

References

- "Profil Daerah > DKI Jakarta" (in Indonesian). Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "Data Jumlah Penduduk DKI Jakarta". Jakarta Open Data. Pemerintah Provinsi DKI Jakarta, Dinas Kependudukan dan Catatan Sipil. 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- see sum from table

- "Indonesia". Badan Pusat Statistik. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2020.

- Indonesia: Java. "Regencies, Cities and Districts – Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Markus Taylor, Tales from the Big Durian, 2009

- Silvita Agmasari (23 June 2017). "Why Is Jakarta Called "The Big Durian"?". Kompas (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Sojourn in the Big Durian". ThingsAsian. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- "The World According to GaWC 2016". GaWC. 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Jakarta to remain ASEAN's capital, secretary-general says". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- "ASEAN, an important regional and global partner". VOV Online Newspaper. 5 August 2017. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Foke lebih yakin lembaga survei asing". Waspada Online (in Indonesian). 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013.

- "Statistik Indonesia 2016" (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2016.

- "Global Metro Monitor". Brookings Institution. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "Jakarta – Urban Challenges Overview – Human Cities Coalition". www.humancities.co. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Cure to sinking Jakarta?". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Jakarta sinks as Indonesian capital and Borneo takes on mantle". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "jaya". Sanskrit Dictionary. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- "krta". Sanskrit Dictionary. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- "History of Jakarta". BeritaJakarta. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011.

- Detailed information on this embassy in Tomé Pires, Armando Cortesão, Francisco Rodrigues, The Suma Oriental of Tome Pires: The Suma oriental of Tome Pires, books 1–5, Introduction p.27 – 32, Armando Cortesão, Publisher Asian Educational Services, 1990, ISBN 81-206-0535-7

- (in Dutch) Kampen, N.F. van (1831). Geschiedenis der Nederlanders buiten Europa, p. 291. Haarlem: De Erven François Bohn.

- (in Dutch) "Batavia zoals het weent en lacht", (17 October 1939), Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, p. 6

- "The capital's 'childhood' names". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Zahorka, Herwig (2007). The Sunda kingdoms of West Java: from Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with the royal center of Bogor : over 1000 years of prosperity and glory. Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka.

- Ayatrohaedi (2005). Sundakala: cuplikan sejarah Sunda berdasarkan naskah-naskah "Panitia Wangsakerta" Cirebon (in Indonesian). Pustaka Jaya. ISBN 978-979-419-330-3.

- Hellman, Jorgen; Thynell, Marie; Voorst, Roanne van (2018). Jakarta: Claiming spaces and rights in the city. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-62044-4.

- Drs. R. Soekmono (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 60.

- Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta, Jilid I: Dokumen-dokumen sejarah Jakarta sampai dengan akhir abad ke-16. Cipta Loka Caraka. 1999.

- "History of Jakarta". BeritaJakarta. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011.

- A History of Modern Indonesia: c. 1300 to the Present. Macmillan International Higher Education. 1981. ISBN 978-1-349-16645-9.

- Heuken, Adolf (2000). Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta Jilid II: Dokumen-dokumen Sejarah Jakarta dari kedatangan kapal pertama Belanda (1596) sampai dengan tahun 1619 (Authentic sources of History of Jakarta part II: Documents of history of Jakarta from the first arrival of Dutch ship (1596) to year 1619). Jakarta: Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka.

- Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-1-74059-154-6.

- P. Nas, Jakarta-Batavia: Socio-cultural Essays, 2000

- "Menteng: Pelopor Kota Taman" (in Indonesian). Badan Perencanaan Kotamadya Jakarta Pusat. 3 November 2007. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009.

- Colonial Economy and Society, 1870–1940 Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Source: U.S. Library of Congress.

- Bakker, K.; Kooy, M.; Shofiani, N.E.; Martijn, E. J. (2008). "Governance Failure: Rethinking the Institutional Dimensions of Urban Water Supply to Poor Households". World Development. 36 (10): 1891. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.09.015.

- Waworoentoe 2013.

- Kusno, Abidin (2000). Behind the Postcolonial: Architecture, Urban Space and Political Cultures. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23615-7.

- Schoppert, P.; Damais, S. (1997). Java Style. Paris: Didier Millet. ISBN 978-962-593-232-3.

- "Why ethnic Chinese are afraid Archived 24 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 12 February 1998.

- Post, BPS Jakarta, Jakarta. "Statistics of DKI Jakarta Province 2008". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "Jakarta". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 September 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- Douglas, M. (1989). "The Environmental Sustainability of Development. Coordination, Incentives and Political Will in Land Use Planning for the Jakarta Metropolis". Third World Planning Review. 11 (2): 211–238. doi:10.3828/twpr.11.2.44113540kqt27180.

- Douglas, M. (1992). "The Political Economy of Urban Poverty and Environmental Management in Asia: Access, Empowerment and Community-based Alternatives". Environment and Urbanization. 4 (2): 9–32. doi:10.1177/095624789200400203.

- Turner, Peter (1997). Java (1st ed.). Melbourne: Lonely Planet. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-86442-314-6.

- Sajor, Edsel E. (2003). "Globalization and the Urban Property Boom in Metro Cebu, Philippines". Development and Change. 34 (4): 713–742. doi:10.1111/1467-7660.00325.

- Friend, Theodore (2003). Indonesian Destinies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01137-3.

- Wages of Hatred Archived 7 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Michael Shari. Business Week.

- Friend, T. (2003). Indonesian Destinies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01137-3.

- Minggu (19 July 2009). "Daftar Serangan Bom di Jakarta". Poskota. Archived from the original on 12 August 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Jakarta holds historic election". BBC News. BBC. 8 August 2007. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- "Ini 21 Caleg DPR yang Terpilih dari DKI Jakarta". Detik.com (in Indonesian). 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Four years on, Ahok's 'Smart City' legacy lives on". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- 'Taxpayer money for the city', The Jakarta Post, 16 July 2011.

- Sita W. Dewi, 'Jokowi spends less, provides more than Foke, say observers' Archived 14 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 9 December 2013.

- Post, The Jakarta. "Editorial: Regional budgets underspent". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Sita W. Dewi, 'Council approves city budget for 2013, higher than proposed' Archived 30 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 29 January 2013.

- "2019 draft city budget to be set at Rp 89 trillion". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Jakarta Proposes Rp95 Trillion Regional Budget Plan for 2020". Tempo. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Jakarta revised budget estimated at Rp 72 trillion". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Central Jakarta Profile". The City Jakarta Administration. Jakarta.go.id. Archived from the original on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "West Jakarta Profile". The City Jakarta Administration. Jakarta.go.id. Archived from the original on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- "South Jakarta Profile". The City Jakarta Administration. Jakarta.go.id. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "East Jakarta Profile". The City Jakarta Administration. Jakarta.go.id. Archived from the original on 14 October 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "North Jakarta Profile". The City Jakarta Administration. Jakarta.go.id. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ""Thousand Island" Profile". The City Jakarta Administration. Jakarta.go.id. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- "BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta". Archived from the original on 3 October 2016.

- "Publikasi Provinsi dan Kabupaten Hasil Sementara SP2010". Bps.go.id. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- "The Tides: Efforts Never End to Repel an Invading Sea". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Based on Governor Decree 2007, No. 171. taken from Statistics DKI Jakarta Provincial Office, Jakarta in Figures, 2008, BPS, the province of DKI Jakarta

- Simanjuntak, T. P. Moan (16 July 2014). "Maja River in Pegadungan Strewn with Water Hyacinth and Mud". Berita Resmi Pemprov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Elyda, Corry (27 December 2014). "BPK slams city's efforts to manage liquid waste". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Post, The Jakarta. "Dutch to study new dike for Jakarta Bay". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "New Ciliwung River Dams Planned as Jakarta Struggles With Latest Floods". 20 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Jatinegara residents complain about underground tunnel project". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- "Indonesia – Halim Perdanakus". Centro de Investigaciones Fitosociológicas. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- "Stations Number 96745" (PDF). Ministry of Energy, Utilities and Climate. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Jakarta, Indonesia – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Jakarta population". Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Cybriwsky and Ford, City profile – Jakarta, 2001

- Jabotabek, the Jakarta metropolitan area

- "After census city plans for 9.6 million" Archived 3 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Jakarta Pos

- "BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta". Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- BRT – Case StudyA 5 – Annex 5 Case Studies and Lessons – Module 2: Bus Rapid Transit (BRT): Toolkit for Feasibility Studies Archived 28 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Sti-india-uttoolkit.adb.org. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- Puslitbang Ekonomi dan Pembangunan, Perubahan Pemanfaatan Tanah di Jabotabek, Jakarta: Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia, 1998