Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands (Dutch: de Lage Landen, French: les Pays-Bas) and historically called the Netherlands (Dutch: de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, refers to a coastal lowland region in northwestern Europe forming the lower basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Geographically and historically, the area includes also parts of France and Germany such as the French Flanders and the German regions of East Frisia and Cleves. During the Middle Ages, the Low Countries were divided in numerous semi-independent principalities.[1][2]

Historically, the regions without access to the sea have linked themselves politically and economically to those with access to form various unions of ports and hinterland,[3] stretching inland as far as parts of the German Rhineland. That is why nowadays some parts of the Low Countries are actually hilly, like Luxembourg and the south of Belgium. Within the European Union, the region's political grouping is still referred to as the Benelux (short for Belgium-Netherlands-Luxembourg).

During the Roman empire the region contained a militarised frontier and contact point between Rome and Germanic tribes.[4] With the collapse of the empire, the Low Countries were the scene of the early independent trading centres that marked the reawakening of Europe in the 12th century. In that period, they rivalled northern Italy as one of the most densely populated regions of Western Europe. Guilds and councils governed most of the cities along with a figurehead ruler; interaction with their ruler was regulated by a strict set of rules describing what the latter could and could not expect. All of the regions mainly depended on trade, manufacturing and the encouragement of the free flow of goods and craftsmen.[5] Dutch and French dialects were the main languages used in secular city life.

Terminology

.svg.png)

Historically, the term Low Countries arose at the Court of the Dukes of Burgundy, who used the term les pays de par deçà ("the lands over here") for the Low Countries as opposed to les pays de par delà ("the lands over there") for the Duchy of Burgundy and the Free County of Burgundy, which were part of their realm but geographically disconnected from the Low Countries.[6][7] Governor Mary of Hungary used both the expressions les pays de par deça and Pays d'Embas ("lands down here"), which evolved to Pays-Bas or Low Countries. Today the term is typically fitted to modern political boundaries[8][9] and used in the same way as the term Benelux.

The name of the country of the Netherlands has the same etymology and origin as the name for the region Low Countries, due to "nether" meaning "low".[10] In the Dutch language itself De Lage Landen is the modern term for Low Countries, and De Nederlanden (plural) is in use for the 16th century domains of Charles V, the historic Low Countries, while Nederland (singular) is in use for the country of the Netherlands. However, in official use, the name of the Dutch kingdom is still Kingdom of the Netherlands, Koninkrijk der Nederlanden (plural). This name derives from the 19th-century origins of the kingdom which originally included present-day Belgium.

In Dutch, and to a lesser extent in English, the Low Countries colloquially means the Netherlands and Belgium, sometimes the Netherlands and Flanders—the Dutch-speaking north of Belgium. For example, a Low Countries derby (Derby der Lage Landen), is a sports event between Belgium and the Netherlands.

Belgium separated in 1830 from the (northern) Netherlands. The new country took its name from Belgica, the Latinised name for the Low Countries, as it was known during the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648). The Low Countries were in that war divided in two parts. On one hand, the northern Federated Netherlands or Belgica Foederata rebelled against the Spanish king; on the other, the southern Royal Netherlands or Belgica Regia remained loyal to the Spanish king.[11] This divide laid the early foundation for the later modern states of Belgium and the Netherlands.

History

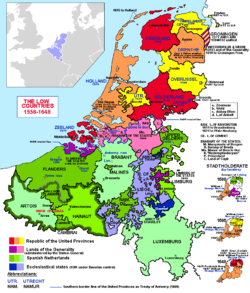

The region politically had its origins in the Carolingian empire; more precisely, most of the people were within the Duchy of Lower Lotharingia.[12][13] After the disintegration of Lower Lotharingia, the Low Countries were brought under the rule of various lordships until they came to be in the hands of the Valois Dukes of Burgundy. Hence, a large part of the Low Countries came to be referred to as the Burgundian Netherlands. After the reign of the Valois Dukes ended, much of the Low Countries were controlled by the House of Habsburg. This area was referred to as the Habsburg Netherlands, which was also called the Seventeen Provinces up to 1581. Even after the political secession of the autonomous Dutch Republic (or "United Provinces") in the north, the term "Low Countries" continued to be used to refer collectively to the region. The region was temporarily united politically between 1815 and 1839, as the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, before this split into the three modern countries of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.

Early history

The Low Countries were part of the Roman provinces of Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior. They were inhabited by Belgic and Germanic tribes. In the 4th and 5th century, Frankish tribes had entered this Roman region and came to run it increasingly independently. They came to be ruled by the Merovingian dynasty, under which dynasty the southern part (below the Rhine) was re-Christianised.

Frankish empire

By the end of the 8th century, the Low Countries formed a core part of a much expanded Francia and the Merovingians were replaced by the Carolingian dynasty.[14] In 800, the Pope crowned and appointed Charlemagne Emperor of the re-established Roman Empire.

After the death of Charlemagne, Francia was divided in three parts among his three grandsons.[15] The middle slice, Middle Francia, was ruled by Lothair I, and thereby also came to be referred to as "Lotharingia" or "Lorraine". Apart from the original coastal County of Flanders, which was within West Francia, the rest of the Low Countries were within the lowland part of this, "Lower Lorraine".

After the death of Lothair, the Low Countries were coveted by the rulers of both West Francia and East Francia. Each tried to swallow the region and to merge it with their spheres of influence. Thus, the Low Countries consisted of fiefs whose sovereignty resided with either the Kingdom of France or the Holy Roman Empire. While the further history the Low Countries can be seen as the object of a continual struggle between these two powers, the title of Duke of Lothier was coveted in the low countries for centuries.[16]

Duchy of Burgundy

In the 14th and 15th century, separate fiefs came gradually to be ruled by a single family through royal intermarriage. This process culminated in the rule of the House of Valois, who were the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy. During the height of Burgundian influence, the Low Countries became the political and economic centre of Northern Europe, noted for its crafts and luxury goods, notably early Netherlandish painting, which is the work of artists who were active in the flourishing cities of Bruges, Ghent, Mechelen, Louvain, Tournai and Brussels, all in present-day Belgium.

Seventeen Provinces

In 1477 the Burgundian holdings in the area passed through an heiress—Mary of Burgundy—to the Habsburgs. Charles V, who inherited the territory in 1506, was named ruler by the States General and styled himself as Heer der Nederlanden ("Lord of the Netherlands"). He continued to rule the territories as a multitude of duchies and principalities until the Low Countries were eventually united into one indivisible territory, the Seventeen Provinces, covered by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549,[17] while retaining existing customs, laws, and forms of government within the provinces.[18]

The Pragmatic Sanction transformed the agglomeration of lands into a unified entity, of which the Habsburgs would be the heirs. By streamlining the succession law in all Seventeen Provinces and declaring that all of them would be inherited by one heir, Charles effectively united the Netherlands as one entity. After Charles' abdication in 1555, the Seventeen Provinces passed to his son, Philip II of Spain.[19]

Division

The Pragmatic Sanction is said to be one example of the Habsburg contest with particularism that contributed to the Dutch Revolt. Each of the provinces had its own laws, customs and political practices. The new policy, imposed from the outside, angered many inhabitants, who viewed their provinces as distinct entities. It and other monarchical acts, such as the creation of bishoprics and promulgation of laws against heresy, stoked resentments, which fired the eruption of the Dutch Revolt.[20]

After the northern Seven United Provinces of the seventeen declared their independence from Habsburg Spain in 1581, the ten provinces of the Southern Netherlands remained occupied by the Army of Flanders under Spanish service and are therefore sometimes called the Spanish Netherlands. In 1713, under the Treaty of Utrecht following the War of the Spanish Succession, what was left of the Spanish Netherlands was ceded to Austria and thus became known as the Austrian Netherlands.

Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer defending the walls during the Siege of Haarlem (1572–1573)

Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer defending the walls during the Siege of Haarlem (1572–1573)_met_storm_verovert%2C_den_29_july_des_jaars_1579_(Jan_Luyken%2C_1679).jpg) Sack of Maastricht by the Tercios de Flandes (Flemish Regiments) in 1579

Sack of Maastricht by the Tercios de Flandes (Flemish Regiments) in 1579 Siege and capture of Tournai (1581)

Siege and capture of Tournai (1581)- Map of Ostend during the siege in 1601

Late Modern Period

The United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815–1830) temporarily united the Low Countries again, before this split into the three modern countries of the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg.

During the early months of World War I (around 1914), The Central Powers invaded the Low Countries of Luxembourg and Belgium in what has been come to be known as the German invasion of Belgium. It led to the German occupation of the two countries. However, the German advance into France was quickly halted, causing a military stalemate for most of the war. In the end, a total of approximately 56,000 people were killed in the invasion.[21]

World War II started in this region, when Adolf Hitler's gaze turned his strategy west toward France. The Low Countries were an easy route around the imposing French Maginot Line. He ordered a conquest of the Low Countries with the shortest possible notice, to forestall the French,and prevent Allied air power from threatening the strategic Ruhr Area{{vague?| / zbxx. of Germany.[22] It would also provide the basis for a long-term air and sea campaign against Britain. As much as possible of the border areas in northern France should be occupied.[23] Germany's Blitzkrieg tactics rapidly overpowered the defences of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

All three countries were occupied from May 1940 until early 1945. During the occupation, their governments were forced into exiled in Britain. In 1944, they signed the London Customs Convention, laying the foundation for the eventual Benelux Economic Union,[24] an important forerunner of the EEC (later the EU).[25]

Literature

One of the Low Countries' earliest literary figures is the blind poet Bernlef, from c. 800, who sang both Christian psalms and pagan verses. Bernlef is representative of the coexistence of Christianity and Germanic polytheism in this time period.[26]:1–2

The earliest examples of written literature include the Wachtendonck Psalms, a collection of twenty five psalms that originated in the Moselle-Frankish region around the middle of the 9th century.[26]:3

See also

References

Citations

- "Low Countries". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- "Low Countries - definition of Low Countries by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Farlex, Inc. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- Matei-Chesnoiu, Monica (2012). Re-imagining Western European Geography in English Renaissance Drama. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 105. ISBN 9780230366305.

- Turner, Barry (2010). The Statesman's Yearbook 2011: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. p. 908. ISBN 9781349586356.

- Braudel, Fernand (1992). Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century, Vol. III: The Perspective of the World. University of California Press. p. 98. ISBN 9780520081161.

- "1. De landen van herwaarts over" (in Dutch). Vre.leidenuniv.nl. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Alastair Duke. "The Elusive Netherlands. The question of national identity in the Early Modern Low Countries on the Eve of the Revolt". Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- "Low Countries". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- "Low Countries | region, Europe". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "netherlands | Origin and meaning of netherlands by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- Buys, Ruben (2015). Sparks of Reason: Vernacular Rationalism in the Low Countries, 1550-1670. Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 17. ISBN 9789087045159.

- "Franks". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- "Lotharingia / Lorraine ( Lothringen )". 5 September 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Ramirez-Faria, Carlos (2007). Concise Encyclopeida Of World History. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 683. ISBN 9788126907755.

- Chopra, Hardev Singh (1974). De Gaulle and European Unity. Abhinav Publications. p. 131. ISBN 9780883862889.

- Jeep, John M. (2017). Routledge Revivals: Medieval Germany (2001): An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 291-295. ISBN 9781351665391.

- "History of Luxembourg: Primary Documents". EuroDocs. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Limm, P. (12 May 2014). "The Dutch Revolt 1559 - 1648". Routledge. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Ronald, Susan (7 August 2012). "Heretic Queen: Queen Elizabeth I and the Wars of Religion". St. Martin's Press. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- State, Paul F. (2008). A Brief History of the Netherlands. Infobase Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 9781438108322. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Great Britain. War Office (14 April 2018). "Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–1920". London H.M. Stationery Off. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Frieser 2005, p. 74.

- "Directive No. 6 Full Text". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Yapou, Eliezer (1998). "Luxembourg: The Smallest Ally". Governments in Exile, 1939–1945. Jerusalem.

- Park, Jehoon; Pempel, T. J.; Kim, Heungchong (2011). Regionalism, Economic Integration and Security in Asia: A Political Economy Approach. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 9780857931276.

- Hermans, edited by Theo (2009). A literary history of the Low Countries. Rochester, N.Y.: Camden House. ISBN 1-57113-293-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

Sources

- Paul Arblaster. A History of the Low Countries. Palgrave Essential Histories Series New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 298 pp. ISBN 1-4039-4828-3.

- J. C. H. Blom and E. Lamberts, eds. History of the Low Countries (1999)

- B. A. Cook. Belgium: A History (2002)

- Jonathan Israel. The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1995)

- Oscar Gelderblom. Cities of Commerce: The Institutional Foundations of International Trade in the Low Countries, 1250–1650 (Princeton University Press, 2013) 293 pp.

- J. A. Kossmann-Putto and E. H. Kossmann. The Low Countries: History of the Northern and Southern Netherlands (1987)

- The Cinema of the Low Countries

- Early Modern Women in the Low Countries

- The Reformation and Revolt in the Low Countries

External links