Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War,[14] was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast Pacific Ocean theater, the South West Pacific theater, the South-East Asian theater, the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Soviet–Japanese War.

| Pacific War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||||

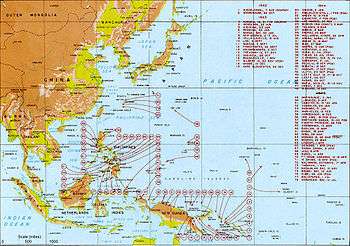

Map showing the main areas of the conflict and Allied landings in the Pacific, 1942–1945 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Major Allies: See section Participants for further details. |

Major Axis: See section Participants for further details. | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Main Allied leaders |

Main Axis leaders | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| History of Japan |

|---|

.svg.png) |

The Second Sino-Japanese War between the Empire of Japan and the Republic of China had been in progress since 7 July 1937, with hostilities dating back as far as 19 September 1931 with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.[15] However, it is more widely accepted[lower-alpha 7][17] that the Pacific War itself began on 7/8 December 1941, when the Japanese invaded Thailand and attacked the British colonies of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong as well as the United States military and naval bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines.[18][19][20]

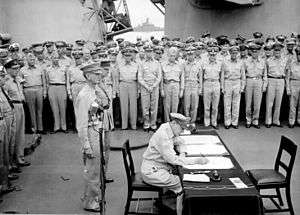

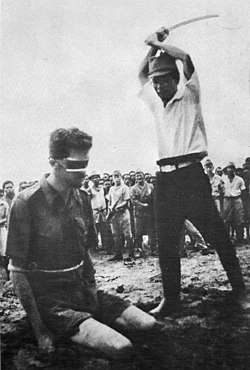

The Pacific War saw the Allies pitted against Japan, the latter aided by Thailand and to a lesser extent by the Axis allies, Germany and Italy. Fighting consisted of some of the largest naval battles in history, and incredibly fierce battles and war crimes across Asia and the Pacific Islands, resulting in immense loss of human life. The war culminated in massive Allied air raids over Japan, and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, accompanied by the Soviet Union's declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria and other territories on 9 August 1945, causing the Japanese to announce an intent to surrender on 15 August 1945. The formal surrender of Japan ceremony took place aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945. After the war, Japan lost all rights and titles to its former possessions in Asia and the Pacific, and its sovereignty was limited to the four main home islands and other minor islands as determined by the Allies.[21] Japan's Shinto Emperor relinquished much of his authority and his divine status through the Shinto Directive in order to pave the way for extensive cultural and political reforms.[22]

Overview

Names for the war

In Allied countries during the war, the "Pacific War" was not usually distinguished from World War II in general, or was known simply as the War against Japan. In the United States, the term Pacific Theater was widely used, although this was a misnomer in relation to the Allied campaign in Burma, the war in China and other activities within the South-East Asian Theater. However, the US Armed Forces considered the China-Burma-India Theater to be distinct from the Asiatic-Pacific Theater during the conflict.

Japan used the name Greater East Asia War (大東亜戦争, Dai Tō-A Sensō), as chosen by a cabinet decision on 10 December 1941, to refer to both the war with the Western Allies and the ongoing war in China. This name was released to the public on 12 December, with an explanation that it involved Asian nations achieving their independence from the Western powers through armed forces of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[23] Japanese officials integrated what they called the Japan–China Incident (日支事変, Nisshi Jihen) into the Greater East Asia War.

During the Allied military occupation of Japan (1945–52), these Japanese terms were prohibited in official documents, although their informal usage continued, and the war became officially known as the Pacific War (太平洋戦争, Taiheiyō Sensō). In Japan, the Fifteen Years' War (十五年戦争, Jūgonen Sensō) is also used, referring to the period from the Mukden Incident of 1931 through 1945.

Participants

Allies

The major Allied participants were the United States and its territories, including the Philippine Commonwealth, where a guerrilla war was waged after its conquest; and China, which had already been engaged in bloody war against Japan since 1937 including both the KMT government National Revolutionary Army and CCP units, such as the guerrilla Eighth Route Army, New Fourth Army, as well as smaller groups. The British Empire was also a major belligerent consisting of British troops along with large numbers of colonial troops from the armed forces of India as well as from Burma, Malaya, Fiji, Tonga; in addition to troops from Australia, New Zealand and Canada. The Dutch government-in-exile (as the possessor of the Dutch East Indies) were also involved, all of whom were members of the Pacific War Council.[24]

Mexico provided some air support in the form of the 201st Fighter Squadron and Free France sent naval support in the form of Le Triomphant and later the Richelieu. From 1944 the French commando group Corps Léger d'Intervention also took part in resistance operations in Indochina. French Indochinese forces faced Japanese forces in a coup in 1945. The commando corps continued to operate after the coup until liberation. Some active pro-allied guerrillas in Asia included the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army, the Korean Liberation Army, the Free Thai Movement and the Việt Minh.

The Soviet Union fought two short, undeclared border conflicts with Japan in 1938 and again in 1939, then remained neutral through the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact of April 1941, until August 1945 when it (and Mongolia) joined the rest of the Allies and invaded the territory of Manchukuo, China, Inner Mongolia, the Japanese protectorate of Korea and Japanese-claimed territory such as South Sakhalin.

Axis powers and aligned states

The Axis-aligned states which assisted Japan included the authoritarian government of Thailand, which formed a cautious alliance with the Japanese in 1941, when Japanese forces issued the government with an ultimatum following the Japanese invasion of Thailand. The leader of Thailand, Plaek Phibunsongkhram, became greatly enthusiastic about the alliance after decisive Japanese victories in the Malayan campaign and in 1942 sent the Phayap Army to assist the invasion of Burma, where former Thai territory that had been annexed by Britain were reoccupied (Occupied Malayan regions were similarly reintegrated into Thailand in 1943). The Allies supported and organized an underground anti-Japanese resistance group, known as the Free Thai Movement, after the Thai ambassador to the United States had refused to hand over the declaration of war. Because of this, after the surrender in 1945, the stance of the United States was that Thailand should be treated as a puppet of Japan and be considered an occupied nation rather than as an ally. This was done in contrast to the British stance towards Thailand, who had faced them in combat as they invaded British territory, and the United States had to block British efforts to impose a punitive peace.[25]

Also involved were members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which included the Manchukuo Imperial Army and Collaborationist Chinese Army of the Japanese puppet states of Manchukuo (consisting of most of Manchuria), and the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime (which controlled the coastal regions of China), respectively. In the Burma campaign, other members, such as the anti-British Indian National Army of Free India and the Burma National Army of the State of Burma were active and fighting alongside their Japanese allies.

Moreover, Japan conscripted many soldiers from its colonies of Korea and Taiwan. Collaborationist security units were also formed in Hong Kong (reformed ex-colonial police), Singapore, the Philippines (also a member of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere), the Dutch East Indies (the PETA), British Malaya, British Borneo, former French Indochina (after the overthrow of the French regime in 1945 (the Vichy French had previously allowed the Japanese to use bases in French Indochina beginning in 1941, following an invasion) as well as Timorese militia. These units assisted the Japanese war effort in their respective territories.

Germany and Italy both had limited involvement in the Pacific War. The German and the Italian navies operated submarines and raiding ships in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, notably the Monsun Gruppe. The Italians had access to concession territory naval bases in China which they utilized (and which was later ceded to collaborationist China by the Italian Social Republic in late 1943). After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent declarations of war, both navies had access to Japanese naval facilities.

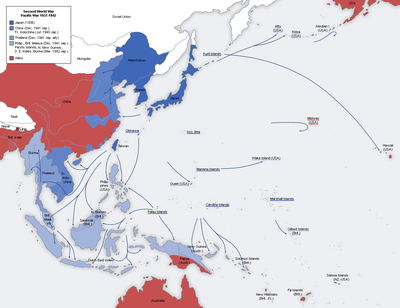

Theaters

Between 1942 and 1945, there were four main areas of conflict in the Pacific War: China, the Central Pacific, South-East Asia and the South West Pacific. US sources refer to two theaters within the Pacific War: the Pacific theater and the China Burma India Theater (CBI). However these were not operational commands.

In the Pacific, the Allies divided operational control of their forces between two supreme commands, known as Pacific Ocean Areas and Southwest Pacific Area.[26] In 1945, for a brief period just before the Japanese surrender, the Soviet Union and Mongolia engaged Japanese forces in Manchuria and northeast China.

The Imperial Japanese Navy did not integrate its units into permanent theater commands. The Imperial Japanese Army, which had already created the Kwantung Army to oversee its occupation of Manchukuo and the China Expeditionary Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War, created the Southern Expeditionary Army Group at the outset of its conquests of South East Asia. This headquarters controlled the bulk of the Japanese Army formations which opposed the Western Allies in the Pacific and South East Asia.

Historical background

Conflict between China and Japan

By 1937, Japan controlled Manchuria and it was also ready to move deeper into China. The Marco Polo Bridge Incident on 7 July 1937 provoked full-scale war between China and Japan. The Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communists suspended their civil war in order to form a nominal alliance against Japan, and the Soviet Union quickly lent support by providing large amount of materiel to Chinese troops. In August 1937, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek deployed his best army to fight about 300,000 Japanese troops in Shanghai, but, after three months of fighting, Shanghai fell.[27] The Japanese continued to push the Chinese forces back, capturing the capital Nanjing in December 1937 and conducted the Nanjing Massacre.[28] In March 1938, Nationalist forces won their first victory at Taierzhuang,[29] but then the city of Xuzhou was taken by the Japanese in May. In June 1938, Japan deployed about 350,000 troops to invade Wuhan and captured it in October.[30] The Japanese achieved major military victories, but world opinion—in particular in the United States—condemned Japan, especially after the Panay incident.

In 1939, Japanese forces tried to push into the Soviet Far East from Manchuria. They were soundly defeated in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol by a mixed Soviet and Mongolian force led by Georgy Zhukov. This stopped Japanese expansion to the north, and Soviet aid to China ended as a result of the signing of the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact at the beginning of its war against Germany.[31]

In September 1940, Japan decided to cut China's only land line to the outside world by seizing French Indochina, which was controlled at the time by Vichy France. Japanese forces broke their agreement with the Vichy administration and fighting broke out, ending in a Japanese victory. On 27 September Japan signed a military alliance with Germany and Italy, becoming one of the three main Axis Powers. In practice, there was little coordination between Japan and Germany until 1944, by which time the US was deciphering their secret diplomatic correspondence.[32]

The war entered a new phase with the unprecedented defeat of the Japanese at the Battle of Suixian–Zaoyang, 1st Battle of Changsha, Battle of Kunlun Pass and Battle of Zaoyi. After these victories, Chinese nationalist forces launched a large-scale counter-offensive in early 1940; however, due to its low military-industrial capacity, it was repulsed by the Imperial Japanese Army in late March 1940.[33] In August 1940, Chinese communists launched an offensive in Central China; in retaliation, Japan instituted the "Three Alls Policy" ("Kill all, Burn all, Loot all") in occupied areas to reduce human and material resources for the communists.[34]

By 1941 the conflict had become a stalemate. Although Japan had occupied much of northern, central, and coastal China, the Nationalist Government had retreated to the interior with a provisional capital set up at Chungking while the Chinese communists remained in control of base areas in Shaanxi. In addition, Japanese control of northern and central China was somewhat tenuous, in that Japan was usually able to control railroads and the major cities ("points and lines"), but did not have a major military or administrative presence in the vast Chinese countryside. The Japanese found its aggression against the retreating and regrouping Chinese army was stalled by the mountainous terrain in southwestern China while the Communists organised widespread guerrilla and saboteur activities in northern and eastern China behind the Japanese front line.

Japan sponsored several puppet governments, one of which was headed by Wang Jingwei.[35] However, its policies of brutality toward the Chinese population, of not yielding any real power to these regimes, and of supporting several rival governments failed to make any of them a viable alternative to the Nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek. Conflicts between Chinese Communist and Nationalist forces vying for territory control behind enemy lines culminated in a major armed clash in January 1941, effectively ending their co-operation.[36]

Japanese strategic bombing efforts mostly targeted large Chinese cities such as Shanghai, Wuhan, and Chongqing, with around 5,000 raids from February 1938 to August 1943 in the later case. Japan's strategic bombing campaigns devastated Chinese cities extensively, killing 260,000–350,934 non-combatants.[37][38]

Tensions between Japan and the West

From as early as 1935 Japanese military strategists had concluded the Dutch East Indies were, because of their oil reserves, of considerable importance to Japan. By 1940 they had expanded this to include Indochina, Malaya, and the Philippines within their concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japanese troop build ups in Hainan, Taiwan, and Haiphong were noted, Imperial Japanese Army officers were openly talking about an inevitable war, and Admiral Sankichi Takahashi was reported as saying a showdown with the United States was necessary.[39]

In an effort to discourage Japanese militarism, Western powers including Australia, the United States, Britain, and the Dutch government in exile, which controlled the petroleum-rich Dutch East Indies, stopped selling oil, iron ore, and steel to Japan, denying it the raw materials needed to continue its activities in China and French Indochina. In Japan, the government and nationalists viewed these embargos as acts of aggression; imported oil made up about 80% of domestic consumption, without which Japan's economy, let alone its military, would grind to a halt. The Japanese media, influenced by military propagandists,[lower-alpha 8] began to refer to the embargoes as the "ABCD ("American-British-Chinese-Dutch") encirclement" or "ABCD line".

Faced with a choice between economic collapse and withdrawal from its recent conquests (with its attendant loss of face), the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters (GHQ) began planning for a war with the Western powers in April or May 1941.

Japanese preparations

In preparation for the war against the United States, which would be decided at sea and in the air, Japan increased its naval budget as well as putting large formations of the Army and its attached air force under navy command. While formerly the IJA consumed the lion's share of the state's military budget due to the secondary role of the IJN in Japan's campaign against China (with a 73/27 split in 1940), from 1942 to 1945 there would instead be a roughly 60/40 split in funds between the army and the navy.[42] Japan's key objective during the initial part of the conflict was to seize economic resources in the Dutch East Indies and Malaya which offered Japan a way to escape the effects of the Allied embargo.[43] This was known as the Southern Plan. It was also decided—because of the close relationship between the United Kingdom and United States,[44][45] and the (mistaken[44]) belief that the US would inevitably become involved—that Japan would also require taking the Philippines, Wake and Guam.

Japanese planning was for fighting a limited war where Japan would seize key objectives and then establish a defensive perimeter to defeat Allied counterattacks, which in turn would lead to a negotiated peace.[46] The attack on the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, by carrier-based aircraft of the Combined Fleet was intended to give the Japanese time to complete a perimeter.

The early period of the war was divided into two operational phases. The First Operational Phase was further divided into three separate parts in which the major objectives of the Philippines, British Malaya, Borneo, Burma, Rabaul and the Dutch East Indies would be occupied. The Second Operational Phase called for further expansion into the South Pacific by seizing eastern New Guinea, New Britain, Fiji, Samoa, and strategic points in the Australian area. In the Central Pacific, Midway was targeted as were the Aleutian Islands in the North Pacific. Seizure of these key areas would provide defensive depth and deny the Allies staging areas from which to mount a counteroffensive.[46]

By November these plans were essentially complete, and were modified only slightly over the next month. Japanese military planners' expectation of success rested on the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union being unable to effectively respond to a Japanese attack because of the threat posed to each by Germany; the Soviet Union was even seen as unlikely to commence hostilities.

The Japanese leadership was aware that a total military victory in a traditional sense against the US was impossible; the alternative would be negotiating for peace after their initial victories, which would recognize Japanese hegemony in Asia.[47] In fact, the Imperial GHQ noted, should acceptable negotiations be reached with the Americans, the attacks were to be canceled—even if the order to attack had already been given. The Japanese leadership looked to base the conduct of the war against America on the historical experiences of the successful wars against China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–05), in both of which a strong continental power was defeated by reaching limited military objectives, not by total conquest.[47]

They also planned, should the United States transfer its Pacific Fleet to the Philippines, to intercept and attack this fleet en route with the Combined Fleet, in keeping with all Japanese Navy prewar planning and doctrine. If the United States or Britain attacked first, the plans further stipulated the military were to hold their positions and wait for orders from GHQ. The planners noted that attacking the Philippines and British Malaya still had possibilities of success, even in the worst case of a combined preemptive attack including Soviet forces.

Japanese offensives, 1941–42

Following prolonged tensions between Japan and the Western powers, units of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army launched simultaneous surprise attacks on Australian, British, Dutch and US forces on 7 December (8 December in Asia/West Pacific time zones).

The locations of this first wave of Japanese attacks included Hawaii, Malaya, Sarawak, Guam, Wake Island, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. Japanese forces also simultaneously invaded southern and eastern Thailand and were resisted for several hours, before the Thai government signed an armistice and entered an alliance with Japan.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

_burning_after_the_Japanese_attack_on_Pearl_Harbor_-_NARA_195617_-_Edit.jpg)

In the early hours of 7 December (Hawaiian time), Japan launched a major surprise carrier-based air strike on Pearl Harbor in Honolulu without explicit warning, which crippled the U.S. Pacific Fleet, left eight American battleships out of action, 188 American aircraft destroyed, and caused the deaths of 2,403 Americans.[48] The Japanese had gambled that the United States, when faced with such a sudden and massive blow and loss of life, would agree to a negotiated settlement and allow Japan free rein in Asia. This gamble did not pay off. American losses were less serious than initially thought: the American aircraft carriers, which would prove to be more important than battleships, were at sea, and vital naval infrastructure (fuel oil tanks, shipyard facilities, and a power station), submarine base, and signals intelligence units were unscathed, and the fact the bombing happened while the US was not officially at war anywhere in the world[lower-alpha 9] caused a wave of outrage across the United States.[48] Japan's fallback strategy, relying on a war of attrition to make the US come to terms, was beyond the IJN's capabilities.[44][49]

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the 800,000-member America First Committee vehemently opposed any American intervention in the European conflict, even as America sold military aid to Britain and the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program. Opposition to war in the US vanished after the attack. On 8 December, the United States,[50] the United Kingdom,[51] Canada,[52] and the Netherlands[53] declared war on Japan, followed by China[54] and Australia[55] the next day. Four days after Pearl Harbor, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, drawing the country into a two-theater war. This is widely agreed to be a grand strategic blunder, as it abrogated both the benefit Germany gained by Japan's distraction of the US and the reduction in aid to Britain, which both Congress and Hitler had managed to avoid during over a year of mutual provocation, which would otherwise have resulted.

South-East Asian campaigns of 1941–42

.jpg)

British, Australian, and Dutch forces, already drained of personnel and matériel by two years of war with Germany, and heavily committed in the Middle East, North Africa, and elsewhere, were unable to provide much more than token resistance to the battle-hardened Japanese. The Allies suffered many disastrous defeats in the first six months of the war. Two major British warships, HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales, were sunk by a Japanese air attack off Malaya on 10 December 1941.[56]

Thailand, with its territory already serving as a springboard for the Malayan Campaign, surrendered within 5 hours of the Japanese invasion.[57] The government of Thailand formally allied with Japan on 21 December. To the south, the Imperial Japanese Army had seized the British colony of Penang on 19 December, encountering little resistance.[58]

Hong Kong was attacked on 8 December and fell on 25 December 1941, with Canadian forces and the Royal Hong Kong Volunteers playing an important part in the defense. American bases on Guam and Wake Island were lost at around the same time.

Following the Declaration by United Nations (the first official use of the term United Nations) on 1 January 1942, the Allied governments appointed the British General Sir Archibald Wavell to the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), a supreme command for Allied forces in Southeast Asia. This gave Wavell nominal control of a huge force, albeit thinly spread over an area from Burma to the Philippines to northern Australia. Other areas, including India, Hawaii, and the rest of Australia remained under separate local commands. On 15 January, Wavell moved to Bandung in Java to assume control of ABDACOM.

In January, Japan invaded British Burma, the Dutch East Indies, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and captured Manila, Kuala Lumpur and Rabaul. After being driven out of Malaya, Allied forces in Singapore attempted to resist the Japanese during the Battle of Singapore, but were forced to surrender to the Japanese on 15 February 1942; about 130,000 Indian, British, Australian and Dutch personnel became prisoners of war.[59] The pace of conquest was rapid: Bali[60] and Timor[61] also fell in February. The rapid collapse of Allied resistance left the "ABDA area" split in two. Wavell resigned from ABDACOM on 25 February, handing control of the ABDA Area to local commanders and returning to the post of Commander-in-Chief, India.

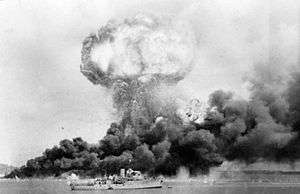

Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft had all but eliminated Allied air power in Southeast Asia[62] and were making attacks on northern Australia, beginning with a psychologically devastating but militarily insignificant attack on the city of Darwin[62] on 19 February, which killed at least 243 people.

At the Battle of the Java Sea in late February and early March, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) inflicted a resounding defeat on the main ABDA naval force, under Admiral Karel Doorman.[63] The Dutch East Indies campaign subsequently ended with the surrender of Allied forces on Java[64] and Sumatra.[65]

In March and April, a powerful IJN carrier force launched a raid into the Indian Ocean. British Royal Navy bases in Ceylon were hit and the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes and other Allied ships were sunk. The attack forced the Royal Navy to withdraw to the western part of the Indian Ocean.[66] This paved the way for a Japanese assault on Burma and India.

In Burma, the British, under intense pressure, made a fighting retreat from Rangoon to the Indo-Burmese border. This cut the Burma Road, which was the western Allies' supply line to the Chinese Nationalists. In March 1942, the Chinese Expeditionary Force started to attack Japanese forces in northern Burma. On 16 April, 7,000 British soldiers were encircled by the Japanese 33rd Division during the Battle of Yenangyaung and rescued by the Chinese 38th Division, led by Sun Li-jen.[67] Cooperation between the Chinese Nationalists and the Communists had waned from its zenith at the Battle of Wuhan, and the relationship between the two had gone sour as both attempted to expand their areas of operation in occupied territories. The Japanese exploited this lack of unity to press ahead in their offensives.

Philippines

On 8 December 1941, Japanese bombers struck American airfields on Luzon. They caught most of the planes on the ground, destroying 103 aircraft, more than half of the US air strength.[68] Two days later, further raids led to the destruction of the Cavite Naval Yard, south of Manila. By 13 December, Japanese attacks had wrecked every major airfield and virtually annihilated American air power.[68] During the previous month before the start of hostilities, a part of the US Asiatic Fleet had been sent to the southern Philippines. However, with little air protection, the remaining surface vessels in the Philippines, especially the larger ships, were sent to Java or to Australia. With their position also equally untenable, the remaining American bombers flew to Australia in mid-December.[68] The only forces that remained to defend the Philippines were the ground troops, a few fighter aircraft, about 30 submarines, and a few small vessels.

On 10 December, Japanese forces began a series of small-scale landings on Luzon. The main landings by the 14th Army took place at Lingayen Gulf on 22 December, with the bulk of the 16th Infantry Division. Another large second landing took place two days later at Lamon Bay, south of Manila, by the 48th infantry Division. As the Japanese troops converged on Manila, General Douglas MacArthur began executing plans to make a final stand on the Bataan Peninsula and the Island of Corregidor in order to deny the use of Manila Bay to the Japanese. A series of withdrawal actions brought his troops safely into Bataan, while the Japanese entered Manila unopposed on 2 January 1942.[69] On 7 January, the Japanese attacked Bataan. After some initial success, they were stalled by disease and casualties, but they could be reinforced while the Americans and Filipinos could not. On 11 March 1942, under orders from President Roosevelt, MacArthur left Corregidor for Australia, and Lieutenant General Jonathan M. Wainwright assumed command in the Philippines. The defenders on Bataan, running low on ammunition and supplies could not hold back a final Japanese offensive. Consequently, Bataan fell on 9 April, with the 76,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war being subjected to a grueling 66-mile (106-km) ordeal that came to be known as the Bataan Death March. On the night of 5–6 May, after an intensive aerial and artillery bombardment of Corregidor, the Japanese landed on the island and General Wainwright surrendered on 6 May. In the southern Philippines, where key ports and airfields had already been seized by the Japanese, the remaining American-Filipino forces surrendered on 9 May.

US and Filipino forces resisted in the Philippines until 9 May 1942, when more than 80,000 soldiers were ordered to surrender. By this time, General Douglas MacArthur, who had been appointed Supreme Allied Commander South West Pacific, had been withdrawn to Australia. The US Navy, under Admiral Chester Nimitz, had responsibility for the rest of the Pacific Ocean. This divided command had unfortunate consequences for the commerce war,[70] and consequently, the war itself.

Threat to Australia

In late 1941, as the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor, most of Australia's best forces were committed to the fight against Axis forces in the Mediterranean Theatre. Australia was ill-prepared for an attack, lacking armaments, modern fighter aircraft, heavy bombers, and aircraft carriers. While still calling for reinforcements from Churchill, the Australian Prime Minister John Curtin called for American support with a historic announcement on 27 December 1941:[71][72]

The Australian Government ... regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say in the direction of the democracies' fighting plan. Without inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.

— Prime Minister John Curtin

Australia had been shocked by the speedy and crushing collapse of British Malaya and the Fall of Singapore in which around 15,000 Australian soldiers were captured and became prisoners of war. Curtin predicted the "battle for Australia" would soon follow. The Japanese established a major base in the Australian Territory of New Guinea in March 1942.[73] On 19 February, Darwin suffered a devastating air raid, the first time the Australian mainland had been attacked. Over the following 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times.

Two battle-hardened Australian divisions were moving from the Middle East for Singapore. Churchill wanted them diverted to Burma, but Curtin insisted on a return to Australia. In early 1942 elements of the Imperial Japanese Navy proposed an invasion of Australia. The Imperial Japanese Army opposed the plan and it was rejected in favour of a policy of isolating Australia from the United States via blockade by advancing through the South Pacific.[74] The Japanese decided upon a seaborne invasion of Port Moresby, capital of the Australian Territory of Papua which would put all of Northern Australia within range of Japanese bomber aircraft.

President Franklin Roosevelt ordered General Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines to formulate a Pacific defence plan with Australia in March 1942. Curtin agreed to place Australian forces under the command of MacArthur, who became Supreme Commander, South West Pacific. MacArthur moved his headquarters to Melbourne in March 1942 and American troops began massing in Australia. Enemy naval activity reached Sydney in late May 1942, when Japanese midget submarines launched a raid on Sydney Harbour. On 8 June 1942, two Japanese submarines briefly shelled Sydney's eastern suburbs and the city of Newcastle.[75]

Allies re-group, 1942–43

In early 1942, the governments of smaller powers began to push for an inter-governmental Asia–Pacific war council, based in Washington, DC. A council was established in London, with a subsidiary body in Washington. However, the smaller powers continued to push for an American-based body. The Pacific War Council was formed in Washington, on 1 April 1942, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, his key advisor Harry Hopkins, and representatives from Britain, China, Australia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada. Representatives from India and the Philippines were later added. The council never had any direct operational control, and any decisions it made were referred to the US–UK Combined Chiefs of Staff, which was also in Washington. Allied resistance, at first symbolic, gradually began to stiffen. Australian and Dutch forces led civilians in a prolonged guerilla campaign in Portuguese Timor.

Japanese strategy and the Doolittle Raid

.jpg)

Having accomplished their objectives during the First Operation Phase with ease, the Japanese now turned to the second.[76] The Second Operational Phase planned to expand Japan's strategic depth by adding eastern New Guinea, New Britain, the Aleutians, Midway, the Fiji Islands, Samoa, and strategic points in the Australian area.[77] However, the Naval General Staff, the Combined Fleet, and the Imperial Army, all had different strategies on the next sequence of operations. The Naval General Staff advocated an advance to the south to seize parts of Australia. However, with large numbers of troops still engaged in China combined with those stationed in Manchuria in a standoff with the Soviet Union, the Imperial Japanese Army declined to contribute the forces necessary for such an operation,[77] this quickly led to the abandonment of the concept. The Naval General Staff still wanted to cut the sea links between Australia and the United States by capturing New Caledonia, Fiji, and Samoa. Since this required far fewer troops, on 13 March the Naval General Staff and the Army agreed to operations with the goal of capturing Fiji and Samoa.[77] The Second Operational Phase began well when Lae and Salamaua, located in eastern New Guinea, were captured on 8 March. However, on 10 March, American carrier aircraft attacked the invasion forces and inflicted considerable losses. The raid had major operational implications since it forced the Japanese to stop their advance in the South Pacific, until the Combined Fleet provided the means to protect future operations from American carrier attack.[77] Concurrently, the Doolittle Raid occurred in April 1942, where 16 bombers took off from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, 600 miles (970 km) from Japan. The raid inflicted minimal material damage on Japanese soil but was a huge morale boost for the United States; it also had major psychological repercussions in Japan, in exposing the vulnerabilities of the Japanese homeland.[78] As the raid was mounted by a carrier task force, it consequently highlighted the dangers the Japanese home islands could face until the destruction of the American carrier forces was achieved.[79] With only Marcus Island and a line of converted trawlers patrolling the vast waters that separate Wake and Kamchatka, the Japanese east coast was left open to attack.[79]

Admiral Yamamoto now perceived that it was essential to complete the destruction of the United States Navy, which had begun at Pearl Harbor.[77] He proposed to achieve this by attacking and occupying Midway Atoll, an objective he thought the Americans would be certain to fight for, as Midway was close enough to threaten Hawaii.[80] During a series of meetings held from 2–5 April, the Naval General Staff and representatives of the Combined Fleet reached a compromise. Yamamoto got his Midway operation, but only after he had threatened to resign. In return, however, Yamamoto had to agree to two demands from the Naval General Staff, both of which had implications for the Midway operation. In order to cover the offensive in the South Pacific, Yamamoto agreed to allocate one carrier division to the operation against Port Moresby. Yamamoto also agreed to include an attack to seize strategic points in the Aleutian Islands simultaneously with the Midway operation. These were enough to remove the Japanese margin of superiority in the coming Midway attack.[81]

Coral Sea

%2C_8_May_1942_(80-G-16651).jpg)

The attack on Port Moresby was codenamed MO Operation and was divided into several parts or phases. In the first, Tulagi would be occupied on 3 May, the carriers would then conduct a wide sweep through the Coral Sea to find and attack and destroy Allied naval forces, with the landings conducted to capture Port Moresby scheduled for 10 May.[81] The MO Operation featured a force of 60 ships led by two carriers: Shōkaku and Zuikaku, one light carrier (Shōhō), six heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and 15 destroyers.[81] Additionally, some 250 aircraft were assigned to the operation including 140 aboard the three carriers.[81] However, the actual battle did not go according to plan; although Tulagi was seized on 3 May, the following day, aircraft from the American carrier Yorktown struck the invasion force.[81] The element of surprise, which had been present at Pearl Harbor, was now lost due to the success of Allied codebreakers who had discovered the attack would be against Port Moresby. From the Allied point of view, if Port Moresby fell, the Japanese would control the seas to the north and west of Australia and could isolate the country. An Allied task force under the command of Admiral Frank Fletcher, with the carriers USS Lexington and USS Yorktown, was assembled to stop the Japanese advance. For the next two days, the American and Japanese carrier forces tried unsuccessfully to locate each other. On 7 May, the Japanese carriers launched a full strike on a contact reported to be enemy carriers, but the report turned out to be false. The strike force found and struck only an oiler, the Neosho, and the destroyer Sims.[82] The American carriers also launched a strike with incomplete reconnaissance, and instead of finding the main Japanese carrier force, they only located and sank Shōhō. On 8 May, the opposing carrier forces finally found each other and exchanged air strikes. The 69 aircraft from the two Japanese carriers succeeded in sinking the carrier Lexington and damaging Yorktown. In return the Americans damaged Shōkaku. Although Zuikaku was left undamaged, aircraft and personnel losses to Zuikaku were heavy and the Japanese were unable to support a landing on Port Moresby. As a result, the MO Operation was cancelled,[83] and the Japanese were subsequently forced to abandon their attempts to isolate Australia.[84] Although they managed to sink a carrier, the battle was a disaster for the Japanese. Not only was the attack on Port Moresby halted, which constituted the first strategic Japanese setback of the war, but all three carriers that were committed to the battle would now be unavailable for the operation against Midway.[83] The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first naval battle fought in which the ships involved never sighted each other, with attacks solely by aircraft.

After Coral Sea, the Japanese had four fleet carriers operational—Sōryū, Kaga, Akagi and Hiryū—and believed that the Americans had a maximum of two—Enterprise and Hornet. Saratoga was out of action, undergoing repair after a torpedo attack, while Yorktown had been damaged at Coral Sea and was believed by Japanese naval intelligence to have been sunk. She would, in fact, sortie for Midway after just three days of repairs to her flight deck, with civilian work crews still aboard, in time to be present for the next decisive engagement.

Midway

.jpg)

Admiral Yamamoto viewed the operation against Midway as the potentially decisive battle of the war which could lead to the destruction of American strategic power in the Pacific,[85] and subsequently open the door for a negotiated peace settlement with the United States, favorable to Japan.[83] For the operation, the Japanese had only four carriers; Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū and Hiryū. Through strategic and tactical surprise, the Japanese would knock out Midway's air strength and soften it for a landing by 5,000 troops.[83] After the quick capture of the island, the Combined Fleet would lay the basis for the most important part of the operation. Yamamoto hoped that the attack would lure the Americans into a trap.[86] Midway was to be bait for the USN which would depart Pearl Harbor to counterattack after Midway had been captured. When the Americans arrived, he would concentrate his scattered forces to defeat them. An important aspect of the scheme was Operation AL, which was the plan to seize two islands in the Aleutians, concurrently with the attack on Midway.[83] Contradictory to persistent myth, the Aleutian operation was not a diversion to draw American forces from Midway, as the Japanese wanted the Americans to be drawn to Midway, rather than away from it.[87] However, in May, Allied codebreakers discovered the planned attack on Midway. Yamamoto's complex plan had no provision for intervention by the American fleet before the Japanese had expected them. Planned surveillance of the American fleet in Pearl Harbor by long-ranged seaplanes did not occur as a result of an abortive identical operation in March. Japanese submarine scouting lines that were supposed to be in place along the Hawaiian Islands were not completed on time, consequently the Japanese were unable to detect the American carriers. In one search area Japanese submarines had arrived on station only a matter of hours ahead of Task Force 17, containing Yorktown, which had passed through just before midnight on 31 May.[88]

The battle began on 3 June, when American aircraft from Midway spotted and attacked the Japanese transport group 700 miles (1,100 km) west of the atoll.[89] On 4 June, the Japanese launched a 108-aircraft strike on the island, the attackers brushing aside Midway's defending fighters but failing to deliver a decisive blow to the island's facilities.[90] Most importantly, the strike aircraft based on Midway had already departed to attack the Japanese carriers, which had been spotted. This information was passed to the three American carriers and a total of 116 carrier aircraft, in addition to those from Midway, were on their way to attack the Japanese. The aircraft from Midway attacked, but failed to score a single hit on the Japanese. In the middle of these uncoordinated attacks, a Japanese scout aircraft reported the presence of an American task force, but it was not until later that the presence of an American carrier was confirmed.[90] Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo was put in a difficult tactical situation in which he had to counter continuous American air attacks and prepare to recover his Midway strike planes, while deciding whether to mount an immediate strike on the American carrier or wait to prepare a proper attack.[91] After quick deliberation, he opted for a delayed but better-prepared attack on the American task force after recovering his Midway strike and properly arming aircraft.[91] However, beginning at 10.22am, American SBD Dauntless dive bombers surprised and successfully attacked three of the Japanese carriers.[91] With their decks laden with fully fueled and armed aircraft, Sōryū, Kaga, and Akagi were turned into blazing wrecks. A single Japanese carrier, Hiryū, remained operational, and launched an immediate counterattack. Both of her attacks hit Yorktown and put her out of action. Later in the afternoon, aircraft from the two remaining American carriers found and destroyed Hiryū. The crippled Yorktown, along with the destroyer Hammann, were both sunk by the Japanese submarine I-168. With the striking power of the Kido Butai having been destroyed, Japan's offensive power was blunted. Early on the morning of 5 June, with the battle lost, the Japanese cancelled the Midway operation and the initiative in the Pacific was in the balance.[92] Parshall and Tully note that although the Japanese lost four carriers, losses at Midway did not radically degrade the fighting capabilities of the IJN aviation as a whole.[93]

New Guinea and the Solomons

Japanese land forces continued to advance in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. From July 1942, a few Australian reserve battalions, many of them very young and untrained, fought a stubborn rearguard action in New Guinea, against a Japanese advance along the Kokoda Track, towards Port Moresby, over the rugged Owen Stanley Ranges. The militia, worn out and severely depleted by casualties, were relieved in late August by regular troops from the Second Australian Imperial Force, returning from action in the Mediterranean theater. In early September 1942 Japanese marines attacked a strategic Royal Australian Air Force base at Milne Bay, near the eastern tip of New Guinea. They were beaten back by Allied forces (primarily Australian Army infantry battalions and Royal Australian Air Force squadrons, with United States Army engineers and an anti-aircraft battery in support), the first defeat of the war for Japanese forces on land.[94]

On New Guinea, the Japanese on the Kokoda Track were within sight of the lights of Port Moresby but were ordered to retreat to the northeastern coast. Australian and US forces attacked their fortified positions and after more than two months of fighting in the Buna–Gona area finally captured the key Japanese beachhead in early 1943.

Guadalcanal

At the same time as major battles raged in New Guinea, Allied forces became aware of a Japanese airfield under construction at Guadalcanal through coastwatchers.[95] On 7 August, US Marines landed on the islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the Solomons. Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, commander of the newly formed Eighth Fleet at Rabaul, reacted quickly. Gathering five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and a destroyer, he sailed to engage the Allied force off the coast of Guadalcanal. On the night of 8–9 August, Mikawa's quick response resulted in the Battle of Savo Island, a brilliant Japanese victory during which four Allied heavy cruisers were sunk,[92] while no Japanese ships were lost. It was one of the worst Allied naval defeats of the war.[92] The victory was only mitigated by the failure of the Japanese to attack the vulnerable transports. Had it been done so, the first American counterattack in the Pacific could have been stopped. The Japanese originally perceived the American landings as nothing more than a reconnaissance in force.[96]

With Japanese and Allied forces occupying various parts of the island, over the following six months both sides poured resources into an escalating battle of attrition on land, at sea, and in the sky. US air cover based at Henderson Field ensured American control of the waters around Guadalcanal during day time, while superior night-fighting capabilities of the Imperial Japanese Navy gave the Japanese the upper hand at night. In August, Japanese and US carrier forces engaged in an indecisive clash known as the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. In October, US cruiser and destroyer forces successfully challenged the Japanese in night-time fighting during the Battle of Cape Esperance, sinking one Japanese cruiser and one destroyer for the loss of one destroyer. During the night of 13 October, two Japanese fast battleships Kongo and Haruna bombarded Henderson Field. The airfield was temporarily disabled but quickly returned to service. On 26 October, Japanese carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku sank USS Hornet (CV-8) and heavily damaged USS Enterprise (CV-6) in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands. The loss of Hornet, coupled with the earlier loss of USS Wasp (CV-7) to the IJN submarine I-19 in September, meant that US carrier strength in the region was reduced to a single ship, Enterprise. However, the two IJN carriers had suffered severe losses in aircraft and pilots as well and had to retire to home waters for repair and replenishment. From 12 November to 15 November, Japanese and American surface ships engaged in fierce night actions in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, one of the only two battles in the Pacific War during which battleships fought each other, that saw two US admirals killed in action and two Japanese battleships sunk.

During the campaign, most of the Japanese aircraft based in the South Pacific were redeployed to the defense of Guadalcanal. Many were lost in numerous engagements with the Allied air forces based at Henderson Field as well as carrier based aircraft. Meanwhile, Japanese ground forces launched repeated attacks on heavily defended US positions around Henderson Field, in which they suffered appalling casualties. To sustain these offensives, resupply was carried out by Japanese convoys, termed the "Tokyo Express" by the Allies. The convoys often faced night battles with enemy naval forces in which they expended destroyers that the IJN could ill-afford to lose. Fleet battles involving heavier ships and even daytime carrier battles resulted in a stretch of water near Guadalcanal becoming known as "Ironbottom Sound" from the multitude of ships sunk on both sides. However, the Allies were much better able to replace these losses. Finally recognizing that the campaign to recapture Henderson Field and secure Guadalcanal had simply become too costly to continue, the Japanese evacuated the island and withdrew in February 1943. In the six-month war of attrition, the Japanese had lost as a result of failing to commit enough forces in sufficient time.[97]

By late 1942, Japanese headquarters had decided to make Guadalcanal their priority. Ironically, the Americans, most notably, U.S. Navy admiral John S. McCain Sr., hoped to use their numerical advantage at Guadalcanal to defeat large numbers of Japanese forces there and progressively drain Japanese man-power. Ultimately nearly 20,000 Japanese died on Guadalcanal compared to just over 7,000 Americans.

Stalemate in China and Southeast Asia

China 1942–1943

In mainland China, the Japanese 3rd, 6th, and 40th Divisions, a grand total of around 120,000 troops, massed at Yueyang and advanced southward in three columns, attempting again to cross the Miluo River to reach Changsha. In January 1942, Chinese forces scored a victory at Changsha, the first Allied success against Japan.[98]

After the Doolittle Raid, the Imperial Japanese Army conducted the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Campaign, with the goal of searching out the surviving American airmen, applying retribution on the Chinese who aided them, and destroying air bases. This operation started on 15 May 1942 with 40 infantry and 15–16 artillery battalions, but was repelled by Chinese forces in September.[99] During this campaign, the Imperial Japanese Army left behind a trail of devastation and also engaged in biological warfare, spreading cholera, typhoid, plague and dysentery pathogens. Chinese estimates put the death toll at 250,000 civilians. Around 1,700 Japanese troops died, out of a total 10,000 who fell ill when Japanese biological weapons infected their own forces.[100][101][102]

On 2 November 1943, Isamu Yokoyama, commander of the Imperial Japanese 11th Army, deployed the 39th, 58th, 13th, 3rd, 116th and 68th Divisions, a total of around 100,000 troops, to attack Changde.[103] During the seven-week Battle of Changde, the Chinese forced Japan to fight a costly campaign of attrition. Although the Imperial Japanese Army initially successfully captured the city, the Chinese 57th Division was able to pin them down long enough for reinforcements to arrive and encircle the Japanese. The Chinese then cut Japanese supply lines, provoking a retreat and Chinese pursuit.[103][104] During the battle, Japan used chemical weapons.[105]

Burma 1942–1943

In the aftermath of the Japanese conquest of Burma, there was widespread disorder and pro-Independence agitation in eastern India and a disastrous famine in Bengal, which ultimately caused up to 3 million deaths. In spite of these, and inadequate lines of communication, British and Indian forces attempted limited counter-attacks in Burma in early 1943. An offensive in Arakan failed, ignominiously in the view of some senior officers,[106] while a long distance raid mounted by the Chindits under Brigadier Orde Wingate suffered heavy losses, but was publicized to bolster Allied morale. It also provoked the Japanese to mount major offensives themselves the following year.

In August 1943 the Allies formed a new South East Asia Command (SEAC) to take over strategic responsibilities for Burma and India from the British India Command, under Wavell. In October 1943 Winston Churchill appointed Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten as its Supreme Commander. The British and Indian Fourteenth Army was formed to face the Japanese in Burma. Under Lieutenant General William Slim, its training, morale and health greatly improved. The American General Joseph Stilwell, who also was deputy commander to Mountbatten and commanded US forces in the China Burma India Theater, directed aid to China and prepared to construct the Ledo Road to link India and China by land. In 1943, the Thai Phayap Army invasion headed to Xishuangbanna at China, but were driven back by the Chinese Expeditionary Force.

Allied offensives, 1943–44

Midway proved to be the last great naval battle for two years. The United States used the ensuing period to turn its vast industrial potential into increased numbers of ships, planes, and trained aircrew.[107] At the same time, Japan, lacking an adequate industrial base or technological strategy, a good aircrew training program, or adequate naval resources and commerce defense, fell further and further behind. In strategic terms the Allies began a long movement across the Pacific, seizing one island base after another. Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like Truk, Rabaul, and Formosa, were neutralized by air attack and bypassed. The goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks, improve the submarine blockade, and finally (only if necessary) execute an invasion.

The US Navy did not seek out the Japanese fleet for a decisive battle, as Mahanian doctrine would suggest (and as Japan hoped); the Allied advance could only be stopped by a Japanese naval attack, which oil shortages (induced by submarine attack) made impossible.[49][70]

Allied offensives on New Guinea and up the Solomons

In the South Western Pacific the Allies now seized the strategic initiative for the first time during the War and in June 1943, launched Operation Cartwheel, a series of amphibious invasions to recapture the Solomon Islands and New Guinea and ultimately isolate the major Japanese forward base at Rabaul. Following the Japanese Invasion of Salamaua–Lae in March, 1943, Cartwheel began with the Salamaua–Lae campaign in Northern New Guinea in April, 1943, which was followed in June to October by the New Georgia campaign, in which the Allies used the Landings on Rendova, Drive on Munda Point and Battle of Munda Point to secure a secretly constructed Japanese airfield at Munda and the rest of New Georgia Islands group. Landings from September until December secured the Treasury Islands and landed Allied troops on Choiseul, Bougainville and Cape Gloucester.

These landings prepared the way for Nimitz's island-hopping campaign towards Japan.

Invasion of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands

In November 1943 US Marines sustained high casualties when they overwhelmed the 4,500-strong garrison at Tarawa. This helped the Allies to improve the techniques of amphibious landings, learning from their mistakes and implementing changes such as thorough pre-emptive bombings and bombardment, more careful planning regarding tides and landing craft schedules, and better overall coordination. Operations on the Gilberts were followed in late-January and mid-February 1944 by further, less costly, landings on the Marshall Islands.

Cairo Conference

On 22 November 1943 US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and ROC Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, met in Cairo, Egypt, to discuss a strategy to defeat Japan. The meeting was also known as the Cairo Conference and concluded with the Cairo Declaration.

Submarine warfare

US submarines, as well as some British and Dutch vessels, operating from bases at Cavite in the Philippines (1941–42); Fremantle and Brisbane, Australia; Pearl Harbor; Trincomalee, Ceylon; Midway; and later Guam, played a major role in defeating Japan, even though submarines made up a small proportion of the Allied navies—less than two percent in the case of the US Navy.[70][108] Submarines strangled Japan by sinking its merchant fleet, intercepting many troop transports, and cutting off nearly all the oil imports essential to weapons production and military operations. By early 1945, Japanese oil supplies were so limited that its fleet was virtually stranded.

The Japanese military claimed its defenses sank 468 Allied submarines during the war.[109] In reality, only 42 American submarines were sunk in the Pacific due to hostile action, with 10 others lost in accidents or as the result of friendly fire.[110] The Dutch lost five submarines due to Japanese attack or minefields,[111] and the British lost three.

American submarines accounted for 56% of the Japanese merchantmen sunk; mines or aircraft destroyed most of the rest.[110] American submariners also claimed 28% of Japanese warships destroyed.[112] Furthermore, they played important reconnaissance roles, as at the battles of the Philippine Sea (June 1944) and Leyte Gulf (October 1944) (and, coincidentally, at Midway in June 1942), when they gave accurate and timely warning of the approach of the Japanese fleet. Submarines also rescued hundreds of downed fliers, including future US president George H. W. Bush.

Allied submarines did not adopt a defensive posture and wait for the enemy to attack. Within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, in retribution against Japan, Roosevelt promulgated a new doctrine: unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. This meant sinking any warship, commercial vessel, or passenger ship in Axis-controlled waters, without warning and without aiding survivors.[lower-alpha 10] At the outbreak of the war in the Pacific, the Dutch admiral in charge of the naval defense of the East Indies, Conrad Helfrich, gave instructions to wage war aggressively. His small force of submarines sank more Japanese ships in the first weeks of the war than the entire British and US navies together, an exploit which earned him the nickname "Ship-a-day Helfrich".[113]

While Japan had a large number of submarines, they did not make a significant impact on the war. In 1942, the Japanese fleet submarines performed well, knocking out or damaging many Allied warships. However, Imperial Japanese Navy (and pre-war US) doctrine stipulated that only fleet battles, not guerre de course (commerce raiding) could win naval campaigns. So, while the US had an unusually long supply line between its west coast and frontline areas, leaving it vulnerable to submarine attack, Japan used its submarines primarily for long-range reconnaissance and only occasionally attacked US supply lines. The Japanese submarine offensive against Australia in 1942 and 1943 also achieved little.[114]

As the war turned against Japan, IJN submarines increasingly served to resupply strongholds which had been cut off, such as Truk and Rabaul. In addition, Japan honored its neutrality treaty with the Soviet Union and ignored American freighters shipping millions of tons of military supplies from San Francisco to Vladivostok,[115] much to the consternation of its German ally.

The US Navy, by contrast, relied on commerce raiding from the outset. However, the problem of Allied forces surrounded in the Philippines, during the early part of 1942, led to diversion of boats to "guerrilla submarine" missions. Basing in Australia placed boats under Japanese aerial threat while en route to patrol areas, reducing their effectiveness, and Nimitz relied on submarines for close surveillance of enemy bases. Furthermore, the standard-issue Mark 14 torpedo and its Mark VI exploder both proved defective, problems which were not corrected until September 1943. Worst of all, before the war, an uninformed US Customs officer had seized a copy of the Japanese merchant marine code (called the "maru code" in the USN), not knowing that the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) had broken it.[116] The Japanese promptly changed it, and the new code was not broken again by OP-20-G until 1943.

Thus, only in 1944 did the US Navy begin to use its 150 submarines to maximum effect: installing effective shipboard radar, replacing commanders deemed lacking in aggression, and fixing the faults in the torpedoes. Japanese commerce protection was "shiftless beyond description,"[lower-alpha 11] and convoys were poorly organized and defended compared to Allied ones, a product of flawed IJN doctrine and training – errors concealed by American faults as much as Japanese overconfidence. The number of American submarines patrols (and sinkings) rose steeply: 350 patrols (180 ships sunk) in 1942, 350 (335) in 1943, and 520 (603) in 1944.[118] By 1945, sinkings of Japanese vessels had decreased because so few targets dared to venture out on the high seas. In all, Allied submarines destroyed 1,200 merchant ships – about five million tons of shipping. Most were small cargo carriers, but 124 were tankers bringing desperately needed oil from the East Indies. Another 320 were passenger ships and troop transports. At critical stages of the Guadalcanal, Saipan, and Leyte campaigns, thousands of Japanese troops were killed or diverted from where they were needed. Over 200 warships were sunk, ranging from many auxiliaries and destroyers to one battleship and no fewer than eight carriers.

Underwater warfare was especially dangerous; of the 16,000 Americans who went out on patrol, 3,500 (22%) never returned, the highest casualty rate of any American force in World War II.[119] The Joint Army–Navy Assessment Committee assessed US submarine credits.[120][121] The Japanese losses, 130 submarines in all,[122] were higher.[123]

Japanese counteroffensives in China, 1944

In mid-1944 Japan mobilized over 500,000 men[124] and launched a massive operation across China under the code name Operation Ichi-Go, their largest offensive of World War II, with the goal of connecting Japanese-controlled territory in China and French Indochina and capturing airbases in southeastern China where American bombers were based.[125] During this time, about 250,000 newly American-trained Chinese troops under Joseph Stilwell and Chinese expeditionary force were forcibly locked in the Burmese theater by the terms of the Lend-Lease Agreement.[125] Though Japan suffered about 100,000 casualties,[126] these attacks, the biggest in several years, gained much ground for Japan before Chinese forces stopped the incursions in Guangxi. Despite major tactical victories, the operation overall failed to provide Japan with any significant strategic gains. A great majority of the Chinese forces were able to retreat out of the area, and later come back to attack Japanese positions at the Battle of West Hunan. Japan was not any closer to defeating China after this operation, and the constant defeats the Japanese suffered in the Pacific meant that Japan never got the time and resources needed to achieve final victory over China. Operation Ichi-go created a great sense of social confusion in the areas of China that it affected. Chinese Communist guerrillas were able to exploit this confusion to gain influence and control of greater areas of the countryside in the aftermath of Ichi-go.[127]

Japanese offensive in India, 1944

After the Allied setbacks in 1943, the South East Asia command prepared to launch offensives into Burma on several fronts. In the first months of 1944, the Chinese and American troops of the Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC), commanded by the American Joseph Stilwell, began extending the Ledo Road from India into northern Burma, while the XV Corps began an advance along the coast in Arakan Province. In February 1944 the Japanese mounted a local counter-attack in Arakan. After early Japanese success, this counter-attack was defeated when the Indian divisions of XV Corps stood firm, relying on aircraft to drop supplies to isolated forward units until reserve divisions could relieve them.

The Japanese responded to the Allied attacks by launching an offensive of their own into India in the middle of March, across the mountainous and densely forested frontier. This attack, codenamed Operation U-Go, was advocated by Lieutenant General Renya Mutaguchi, the recently promoted commander of the Japanese Fifteenth Army; Imperial General Headquarters permitted it to proceed, despite misgivings at several intervening headquarters. Although several units of the British Fourteenth Army had to fight their way out of encirclement, by early April they had concentrated around Imphal in Manipur state. A Japanese division which had advanced to Kohima in Nagaland cut the main road to Imphal, but failed to capture the whole of the defences at Kohima. During April, the Japanese attacks against Imphal failed, while fresh Allied formations drove the Japanese from the positions they had captured at Kohima.

As many Japanese had feared, Japan's supply arrangements could not maintain her forces. Once Mutaguchi's hopes for an early victory were thwarted, his troops, particularly those at Kohima, starved. During May, while Mutaguchi continued to order attacks, the Allies advanced southwards from Kohima and northwards from Imphal. The two Allied attacks met on 22 June, breaking the Japanese siege of Imphal. The Japanese finally broke off the operation on 3 July. They had lost over 50,000 troops, mainly to starvation and disease. This represented the worst defeat suffered by the Imperial Japanese Army to that date.[128]

Although the advance in Arakan had been halted to release troops and aircraft for the Battle of Imphal, the Americans and Chinese had continued to advance in northern Burma, aided by the Chindits operating against the Japanese lines of communication. In the middle of 1944 the Chinese Expeditionary Force invaded northern Burma from Yunnan. They captured a fortified position at Mount Song.[129] By the time campaigning ceased during the monsoon rains, the NCAC had secured a vital airfield at Myitkyina (August 1944), which eased the problems of air resupply from India to China over "The Hump".

Beginning of the end in the Pacific, 1944

In May 1943, the Japanese prepared Operation Z or the Z Plan, which envisioned the use of Japanese naval power to counter American forces threatening the outer defense perimeter line. This line extended from the Aleutians down through Wake, the Marshall and Gilbert Islands, Nauru, the Bismarck Archipelago, New Guinea, then westward past Java and Sumatra to Burma.[130] In 1943–44, Allied forces in the Solomons began driving relentlessly to Rabaul, eventually encircling and neutralizing the stronghold. With their position in the Solomons disintegrating, the Japanese modified the Z Plan by eliminating the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, and the Bismarck Archipelago as vital areas to be defended. They then based their possible actions on the defense of an inner perimeter, which included the Marianas, Palau, Western New Guinea, and the Dutch East Indies. Meanwhile, in the Central Pacific the Americans initiated a major offensive, beginning in November 1943 with landings in the Gilbert Islands.[131] The Japanese were forced to watch helplessly as their garrisons in the Gilberts and then the Marshalls were crushed.[131] The strategy of holding overextended island garrisons was fully exposed.[132]

In February 1944, the US Navy's fast carrier task force, during Operation Hailstone, attacked the major naval base of Truk. Although the Japanese had moved their major vessels out in time to avoid being caught at anchor in the atoll, two days of air attacks resulted in significant losses to Japanese aircraft and merchant shipping.[132] The Japanese were forced to abandon Truk and were now unable to counter the Americans on any front on the perimeter. Consequently, the Japanese retained their remaining strength in preparation for what they hoped would be a decisive battle.[132] The Japanese then developed a new plan, known as A-GO. A-GO envisioned a decisive fleet action that would be fought somewhere from the Palaus to the Western Carolines.[133] It was in this area that the newly formed Mobile Fleet along with large numbers of land-based aircraft, would be concentrated. If the Americans attacked the Marianas, they would be attacked by land-based planes in the vicinity. Then the Americans would be lured into the areas where the Mobile Fleet could defeat them.[133]

Marianas and Palaus

On 12 March 1944, the Joint Chiefs of Staff directed the occupation of the Northern Marianas, specifically the islands of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam. A target date was set for 15 June. All forces for the Marianas operation were to be commanded by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. The forces assigned to his command consisted of 535 warships and auxiliaries together with a ground force of three and a half Marine divisions and one reinforced Army division, a total of more than 127,500 troops.[134] For the Americans, the Marianas operation would provide the following benefits: the interruption of the Japanese air pipeline to the south; the development of advanced naval bases for submarine and surface operations; the establishment of airfields to base B-29s from which to bomb the Japanese Home Islands; the choice among several possible objectives for the next phase of operations, which would keep the Japanese uncertain of American intentions. It was also hoped that this penetration of the Japanese inner defense zone, which was a little more than 1,250 miles (2,010 km) from Tokyo, might force the Japanese fleet out for a decisive engagement.[135] The ability to plan and execute such a complex operation in the space of 90 days was indicative of Allied logistical superiority.

On 15 June, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions supported by a naval bombardment group totaling eight battleships, eleven cruisers, and twenty-six destroyers landed on Saipan. However, Japanese fire was so effective that the first day's objective was not reached until Day 3. After fanatic Japanese resistance, the Marines captured Aslito airfield in the south on 18 June. US Navy Seabees quickly made the field operational for use for American aircraft. On 22 June, the front of the northward advancing 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions widened to such a degree that General Holland Smith ordered the bulk of the Army's 27th Division to take over the line in the center, between the two US Marine divisions. The 27th Division was late taking its position and was late in making advances so that the inner flanks of the marine divisions became exposed. A giant U was formed with the 27th at the base 1,500 yards (1.4 km) behind the advancing formations. This presented the Japanese with an opportunity to exploit it. On 24 June, General Holland Smith replaced General Ralph C. Smith, the commanding general of the 27th Division, who he believed lacked an aggressive spirit.[136]

Nafutan, Saipan's southern point, was secured on 27 June, after the Japanese troops trapped there expended themselves in a desperate attempt to break through. In the north, Mount Tapotchau, the highest point on the island, was taken on 27 June. The Marines then steadily advanced northward. On the night of 6–7 July, a banzai attack took place in which three to four thousand Japanese made a fanatical charge that penetrated the lines near Tanapag before being wiped out. Following this attack, hundreds of the native population committed mass suicide by throwing themselves off the cliffs onto the rocks below near the northern tip of the island. On 9 July, two days after the banzai attack, organized resistance on Saipan ceased. The US Marines reached northernmost tip of Saipan, Marpi Point, twenty-four days after the landing. Only isolated groups of hidden Japanese troops remained.[137]

A month after the invasion of Saipan, the US recaptured Guam and captured Tinian. Once captured, the islands of Saipan and Tinian were used extensively by the United States military as they finally put mainland Japan within round-trip range of American B-29 bombers. In response, Japanese forces attacked the bases on Saipan and Tinian from November 1944 to January 1945. At the same time and afterwards, the United States Army Air Forces based out of these islands conducted an intense strategic bombing campaign against the Japanese cities of military and industrial importance, including Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe and others.

The invasion of Peleliu in the Palau Islands on 15 September, was notable for a drastic change in Japanese defensive tactics, resulting in the highest casualty rate amongst US forces in an amphibious operation during the Pacific War.[138] Instead of the predicted four days, it took until 27 November to secure the island. The ultimate strategic value of the landings is still contested.[139]

Philippine Sea

.jpg)

When the Americans landed on Saipan in the Marianas the Japanese viewed holding Saipan as an imperative. Consequently, the Japanese responded with their largest carrier force of the war: the nine-carrier Mobile Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa, supplemented by an additional 500 land-based aircraft. Facing them was the US Fifth Fleet under the command of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, which contained 15 fleet carriers and 956 aircraft. The clash was the largest carrier battle in history. The battle did not turn out as the Japanese had hoped. During the previous month, US destroyers had destroyed 17 out of 25 submarines in Ozawa's screening force[140][141] and repeated American air raids destroyed the Japanese land-based aircraft.

On 19 June, a series of Japanese carrier air strikes were shattered by strong American defenses. The result was later dubbed the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. All US carriers had combat-information centers, which interpreted the flow of radar data and radioed interception orders to the combat air patrols. The few Japanese attackers that managed to reach the US fleet in a staggered sequence encountered massive anti-aircraft fire with proximity fuzes. Only one American warship was slightly damaged. On the same day, Shōkaku was hit by four torpedoes from the submarine Cavalla and sank with heavy loss of life. The Taihō was also sunk by a single torpedo, from the submarine Albacore. The next day, the Japanese carrier force was subjected to an American carrier air attack and suffered the loss of the carrier Hiyō.[132] The four Japanese air strikes involved 373 carrier aircraft, of which 130 returned to the carriers.[142] Many of these survivors were subsequently lost when Taihō and Shōkaku were sunk by American submarine attacks. After the second day of the battle, losses totaled three carriers and 445 aircrew with more than 433 carrier aircraft and around 200 land-based aircraft. The Americans lost 130 aircraft and 76 aircrew, many losses due to aircraft running out of fuel returning to their carriers at night.

Although the defeat at the Philippine Sea was severe in terms of the loss of the three fleet carriers Taihō, Shōkaku and the Hiyō, the real disaster was the annihilation of the carrier air groups.[143] These losses to the already outnumbered Japanese fleet air arm were irreplaceable. The Japanese had spent the better part of a year reconstituting their carrier air groups, and the Americans had destroyed 90% of it in two days. The Japanese had only enough pilots left to form the air group for one of their light carriers. The Mobile Fleet returned home with only 35 aircraft of the 430 with which it had begun the battle.[132] The battle ended in a total Japanese defeat and resulted in the virtual end of their carrier force.[144]

Leyte Gulf, 1944

The disaster at the Philippine Sea left the Japanese with two choices: either to commit their remaining strength in an all-out offensive or to sit by while the Americans occupied the Philippines and cut the sea lanes between Japan and the vital resources from the Dutch East Indies and Malaya. Thus the Japanese devised a plan which represented a final attempt to force a decisive battle by utilizing their last remaining strength – the firepower of its heavy cruisers and battleships – against the American beachhead at Leyte. The Japanese planned to use their remaining carriers as bait in order to lure the American carriers away from Leyte Gulf long enough for the heavy warships to enter and to destroy any American ships present.[145]