Albertine Rift

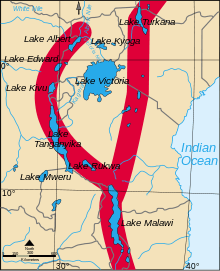

The Albertine Rift is the western branch of the East African Rift, covering parts of Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. It extends from the northern end of Lake Albert to the southern end of Lake Tanganyika. The geographical term includes the valley and the surrounding mountains.[1]

.jpg)

Geology

The Albertine Rift and the mountains are the result of tectonic movements that are gradually splitting the Somali Plate away from the rest of the African continent. The mountains surrounding the rift are composed of uplifted Pre-Cambrian basement rocks, overlaid in parts by recent volcanic rocks.

Lakes and rivers

The northern part of the rift is crossed by two large mountain ranges, the Rwenzori Mountains between Lake Albert and Lake Rutanzige (formerly Lake Edward) and the Virunga Mountains between Lake Rutanziga and Lake Kivu. The Virungas form a barrier between the Nile Basin to the north and east and the Congo Basin to the west and south. Lake Rutenzige is fed by several large rivers, the Rutshuru River being one, and drains to the north through the Semliki River into Lake Albert. The Victoria Nile flows from Lake Victoria into the northern end of Lake Albert and exits as the White Nile from a point slightly to the west, flowing north to the Mediterranean.[2]

South of the Virungu, Lake Kivu drains to the south into Lake Tanganyika through the Ruzizi River. Lake Tanganyika then drains into the Congo River via the Lukuga River.[2] It seems likely that the present hydrological system was established quite recently when the Virunga volcanoes erupted and blocked the northward flow of water from Lake Kivu into Lake Edward, causing it instead to discharge southward into Lake Tanganyika. Before that Lake Tanganyika, or separate sub-basins in what is now the lake, may have had no outlet other than evaporation.[3] The Lukuga has formed relatively recently, providing a route through which aquatic species of the Congo Basin could colonize Lake Tanganyika, which formerly had distinct fauna.[4]

Mountains

From north to south the mountains include the Lendu Plateau, Rwenzori Mountains, Virunga Mountains and Itombwe Mountains.[5] The Ruwenzori mountains have been identified with Ptolemy's "Mountains of the Moon". The range covers an area 120 kilometres (75 mi) long by 65 kilometres (40 mi) wide. This range includes Mount Stanley 5,119 metres (16,795 ft), Mount Speke 4,890 metres (16,040 ft) and Mount Baker 4,843 metres (15,889 ft).[6] The Virunga Massif along the border between Rwanda and the DRC consists of eight volcanoes. Two of these, Nyamuragira and Nyiragongo, are still highly active.[7]

Isolated mountain blocks further to the south include Mount Bururi in southern Burundi, the Kungwe-Mahale Mountains in western Tanzania, and Mount Kabobo and the Marungu Mountains in the DRC on the shores of Lake Tanganyika.[5] Most of the massifs rise to between 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) and 3,500 metres (11,500 ft).[8]

Ecology

The Albertine Rift montane forests are important eco-regions.[5] Transitional forests, intermediate between lowland and montane forest, are found at elevations from around 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) to 1,750 metres (5,740 ft). Montane forest covers the slopes from around 1,600 metres (5,200 ft) to 3,500 metres (11,500 ft). Above 2,400 metres (7,900 ft) there are areas of bamboo and elfin forest. Heather and grasses predominate above 3,500 metres (11,500 ft). The ecology is threatened by deforestation as a growing population seeks new farmland. Illegal timber extraction is another problem, and artisanal gold mining causes some local damage.[8]

See also

References

- Owiunji & Plumptre 2011, p. 164.

- Erfurt-Cooper & Cooper 2010, p. 35-36.

- Clark 1969, p. 35.

- Hughes & Hughes 1992, p. 562.

- WWF.

- Erfurt-Cooper & Cooper 2010, p. 37.

- Erfurt-Cooper & Cooper 2010, p. 36.

- Birdlife.

Sources

- Birdlife. "Albertine Rift mountains". Birdlife International. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- Clark, John Desmond (1969). Kalambo Falls prehistoric site, Volume 1. CUP Archive.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erfurt-Cooper, Patricia; Cooper, Malcolm (2010). Volcano and Geothermal Tourism: Sustainable Geo-Resources for Leisure and Recreation. Earthscan. ISBN 1-84407-870-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, R. H.; Hughes, J. S. (1992). A directory of African wetlands. IUCN. ISBN 2-88032-949-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Owiunji, I.; Plumptre, A.J. (2011). "The importance of cloud forest sites in the conservation of endemic and threatened species of the Albertine Rift". Tropical Montane Cloud Forests: Science for Conservation and Management. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521760356.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Albertine Rift montane forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2011-12-19.