Auckland Islands

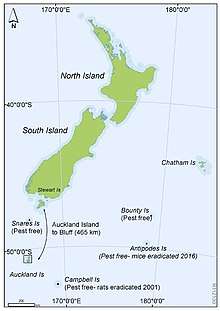

The Auckland Islands (Māori: Motu Maha or Maungahuka)[1] are an archipelago of New Zealand, lying 465 kilometres (290 mi) south of the South Island. The main Auckland Island, occupying 510 km2 (200 sq mi), is surrounded by smaller Adams Island, Enderby Island, Disappointment Island, Ewing Island, Rose Island, Dundas Island, and Green Island, with a combined area of 626 km2 (240 sq mi).[2] The islands have no permanent human inhabitants.

| Motu Maha or Maungahuka (Māori) | |

|---|---|

The Auckland Islands as seen by STS-89 in 1998, with the northwest towards the top of the image | |

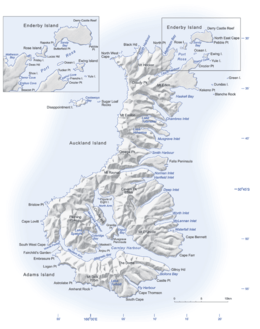

Map of the Auckland Islands | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Southern Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 50.7°S 166.1°E |

| Archipelago | Auckland Islands |

| Total islands | 7 |

| Major islands | Auckland Island, Adams Island, Enderby Island, Disappointment Island, Ewing Island, Dundas Island, Green Island |

| Area | 625.64 km2 (241.56 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 705 m (2,313 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Dick |

| Administration | |

| Area Outside Territorial Authority | New Zealand Subantarctic Islands |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 (2015) |

The islands are listed with the New Zealand Outlying Islands. The islands are an immediate part of New Zealand, but not part of any region or district, but instead Area Outside Territorial Authority, like all the other outlying islands except the Solander Islands.

Ecologically, the Auckland Islands form part of the Antipodes Subantarctic Islands tundra ecoregion. Along with other New Zealand Sub-Antarctic Islands, they were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998.[3]

Geography

The Auckland Islands lie 360 kilometres (220 mi) south of Stewart Island, and 465 kilometres (290 mi) from the South Island port of Bluff, between the latitudes 50° 30' and 50° 55' S and longitudes 165° 50' and 166° 20' E.

They include Auckland Island, Adams Island, Enderby Island, Disappointment Island, Ewing Island, Rose Island, Dundas Island and Green Island, with a combined area of 626 square kilometres (240 sq mi). The islands are close to each other, separated by narrow channels, and the coastline is rugged, with numerous deep inlets.

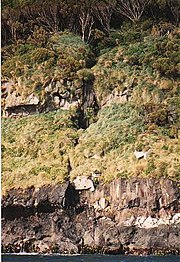

Auckland Island, the main island, has an approximate land area of 510 km2 (197 sq mi), and a length of 42 km (26 mi). It is notable for its steep cliffs and rugged terrain, which rises to over 600 m (1,969 ft). Prominent peaks include Cavern Peak (659 m or 2,162 ft), Mount Raynal (635 m or 2,083 ft), Mount D'Urville (630 m or 2,067 ft), Mount Easton (610 m or 2,001 ft), and the Tower of Babel (550 m or 1,804 ft). The southern end of the island broadens to a width of 26 km (16 mi).[4]

Here, the narrow channel of Carnley Harbour (the Adams Straits on some maps) separates the main island from the roughly triangular Adams Island (area approximately 100 km2 or 39 sq mi), which is even more mountainous, reaching a height of 705 m (2,313 ft) at Mount Dick. The channel is the remains of the crater of an extinct volcano, and Adams Island and the southern part of the main island form the crater rim. The main island features many sharply incised inlets, notably Port Ross at the northern end.

The group includes numerous other smaller islands, notably Disappointment Island (10 km or 6.2 mi northwest of the main island) and Enderby Island (1 km or 0.62 mi off the northern tip of the main island), each covering less than 5 km2 (2 sq mi).

Most of the islands have a volcanic origin, with the archipelago dominated by two 12-million-year-old Miocene volcanoes, subsequently eroded and dissected.[5] These rest on older volcanic rocks 15–25 million years old with some older granites and fossil-bearing sedimentary rocks from around 100 million years ago.[6]

Climate

Port Ross features a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc according to the Köppen climate classification system). Like many other Subpolar oceanic climates, Port Ross, along with the Auckland Islands in general, are characterised by the near-constant overcast weather and never being too hot or too cold.

| Climate data for Port Ross (1941-1945) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.3 (65.0) |

19.3 (66.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

12.3 (54.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.4 (54.4) |

12.1 (53.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.8 (60.5) |

15.6 (60.0) |

17.3 (63.2) |

19.3 (66.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.8 (58.6) |

14.4 (58.0) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.8 (46.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.9 (49.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.1 (53.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

11.2 (52.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.8 (49.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.1 (42.9) |

5.8 (42.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

7.8 (46.1) |

8.4 (47.2) |

9.8 (49.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

4.1 (39.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

2.9 (37.2) |

3.8 (38.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.4 (36.3) |

1.4 (34.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−1.8 (28.7) |

−2.6 (27.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−1.8 (28.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−2.6 (27.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 110 (4.2) |

120 (4.8) |

140 (5.5) |

180 (7.0) |

150 (5.9) |

150 (5.8) |

84 (3.3) |

110 (4.3) |

120 (4.9) |

100 (4.1) |

110 (4.4) |

120 (4.9) |

1,494 (59.1) |

| Average precipitation days | 22 | 22 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 26 | 311 |

| Source: https://newzealandecology.org/system/files/articles/ProNZES12_37.pdf | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Port Ross (1941-1945) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 10.4 (50.8) |

10.5 (51.0) |

10.2 (50.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

8.5 (47.4) |

7.8 (46.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

7.2 (45.1) |

7.7 (46.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

8.8 (47.9) |

9.5 (49.2) |

8.8 (47.9) |

| Climate data for Carnley Harbour (1941-1945) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.1 (64.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.2 (52.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.6 (58.2) |

14.7 (58.4) |

15.7 (60.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.3) |

13.4 (56.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.7 (51.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

7.9 (46.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

9.2 (48.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.6 (51.0) |

11.6 (52.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

5.7 (42.2) |

6.1 (42.9) |

5.6 (42.0) |

6.4 (43.6) |

6.8 (44.3) |

7.1 (44.7) |

8.2 (46.7) |

7.5 (45.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.3 (45.2) |

7.3 (45.2) |

5.6 (42.0) |

3.3 (38.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.4 (38.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.8 (38.9) |

4.1 (39.3) |

4.2 (39.5) |

5.1 (41.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

2.9 (37.3) |

1.2 (34.1) |

−1.7 (29.0) |

−0.1 (31.9) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−0.8 (30.5) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−0.4 (31.2) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−1.7 (29.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 180 (7.2) |

140 (5.7) |

140 (5.7) |

250 (9.8) |

240 (9.3) |

190 (7.4) |

130 (5.3) |

190 (7.3) |

150 (5.9) |

130 (5.1) |

140 (5.4) |

220 (8.6) |

2,100 (82.7) |

| Average precipitation days | 25 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 30 | 29 | 29 | 25 | 28 | 331 |

| Source: https://newzealandecology.org/system/files/articles/ProNZES12_37.pdf | |||||||||||||

Carnley Harbour also features a subpolar oceanic climate (Cfc according to the Köppen climate classification system), though it exaggerates the features shown in Port Ross, as it is much wetter and a lot more affected by ocean-moderation.

The Auckland Islands have a fairly constant cool and wet weather year-round, with neither winter being excessively cold nor summer excessively hot. The climate is most similar to that seen in the Faroe Islands and Aleutian Islands.

History

Discovery and early exploitation

Evidence exists that Polynesian voyagers first discovered the Auckland Islands. Traces of Polynesian settlement, possibly dating to the 13th century, have been found by archaeologists on Enderby Island.[7] This is the most southerly settlement by Polynesians yet known.[8]

The whaler Ocean discovered the islands in 1806, finding them uninhabited.[9] Captain Abraham Bristow named them "Lord Auckland's" on 18 August 1806 in honour of his father's friend William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland. Bristow worked for the businessman Samuel Enderby, the namesake of Enderby Island. The following year Bristow returned on Sarah to claim the archipelago for Britain. The explorers Dumont D'Urville in 1839, and James Clark Ross visited in 1839 and in 1840 respectively.

Whalers and sealers set up temporary bases, the islands becoming one of the principal sealing stations in the Pacific in the years immediately after their discovery.[9] By 1812, so many seals had been killed that the islands lost their commercial importance and sealers redirected their efforts towards Campbell and Macquarie Islands. Visits to the islands declined, although recovering seal populations allowed a modest revival in sealing in the mid-1820s.

The sealing era lasted from 1807 till 1894, during which time 82 vessels are recorded as visiting for sealing purposes. Some 11 of these ships were wrecked off-shore.[10] Relics of the sealing period include inscriptions, the remains of huts and graves.

Settlement

Now uninhabited, the islands saw unsuccessful settlements in the mid-19th century. In 1842 a small party of Māori and their Moriori slaves from the Chatham Islands migrated to the archipelago, surviving for some 20 years on sealing and flax growing. Samuel Enderby's grandson, Charles Enderby, proposed a community based on agriculture and whaling in 1846. This settlement, established at Port Ross in 1849 and named Hardwicke, lasted only two and a half years.[11]

The Auckland Islands were part of the Colony of New Zealand under the Letters Patent of April 1842 which fixed the southern boundary of New Zealand at 53° south, but they were then excluded by the Act of 1846 which defined the southern boundary at 47° 10' south; however they were again included by the New Zealand Boundaries Act of 1863, an act of the Imperial Parliament at Westminster which extended the boundaries of the colony once more.[12]

Shipwrecks

The rocky coasts of the islands have proven disastrous for several ships. The Grafton, captained by Thomas Musgrave, was wrecked in Carnley Harbour in 1864. Madelene Ferguson Allen's narrative about her great-grandfather, Robert Holding, and the wreck of the Scottish sailing ship Invercauld, wrecked in the Auckland Islands a few months later in 1864, counterpoints the Grafton story.[13] François Édouard Raynal wrote Wrecked on a Reef.[14]

In 1866, one of New Zealand's most famous shipwrecks, that of the General Grant, occurred on the western coast. Ten survivors waited for rescue on Auckland Island for 18 months. Several attempts have failed to salvage its cargo, allegedly including bullion.[15]

Because of the probability of wrecks around the islands, calls arose for the establishment of emergency depots for castaways in 1868. The New Zealand authorities established and maintained three such depots, at Port Ross, Norman Inlet and Carnley Harbour from 1887. They also cached additional supplies, including boats (to help reach the depots) and 40 finger-posts (which had smaller amounts of supplies), around the islands.[16]

A further maritime tragedy occurred in 1907, with the loss of the Dundonald and 12 of her crew, off Disappointment Island. The 15 survivors lived off the supplies in the Auckland Island depot.[17]

In 2019 a helicopter with three passengers crashed into the ocean near Enderby Island, when they were on route to uplift an ill man on a fishing trawler.[18] The three passengers all survived the crash, and were found the next day with only minor injuries.[19] The rescue effort was led by Richard Hayes.[20]

Scientific research and reserve

The Sub-Antarctic Islands Scientific Expedition of 1907 spent 10 days on the islands conducting a magnetic survey and taking botanical, zoological and geological specimens.

From 1941 to 1945, the islands hosted a New Zealand meteorological station as part of a coastwatching programme staffed by scientist volunteers and known for security reasons as the "Cape Expedition".[21] The staff included Robert Falla, later an eminent New Zealand scientist. Currently the islands have no inhabitants, although scientists visit regularly and the authorities allow limited tourism on Enderby Island and Auckland Island.

The marine environment surrounding the archipelago became a marine mammal sanctuary in 1993 and, unusually, also a marine reserve in 2003, measuring 4,980 km2 (1,920 sq mi).[22] The Subantarctic Islands marine reserves around the Auckland, Antipodes, Bounty and Campbell Islands combined form the largest natural sanctuary in New Zealand.[23][24]

Ecology

Plants

The botany of the islands was first described in the Flora of Lord Auckland and Campbell's Islands, a product of the Ross expedition of 1839–43, written by Joseph Dalton Hooker and published by Reeve Brothers in London between 1843 and 1845.[25]

The vegetation of the islands sub-divides into distinct altitudinal zones. Inland from the salt-spray zone, the fringes of the islands predominantly feature forests of southern rata Metrosideros umbellata, and in places the subantarctic tree daisy (Olearia lyallii), probably introduced by sealers.[26] Above this exists a subalpine shrub zone dominated by Dracophyllum, Coprosma and Myrsine (with some rata). At higher elevations tussock grass and megaherb communities dominate the flora.

Invertebrates

The islands host the largest communities of subantarctic invertebrates, with 24 species of spider, 11 species of springtail and over 200 insects.[27] These include 57 species of beetle, 110 flies and 39 moths. The islands also boast an endemic genus and species of wētā, Dendroplectron aucklandensis.

Fresh and saltwater fauna

The freshwater environments of the islands host a freshwater fish, the koaro or climbing galaxias, which lives in saltwater as a juvenile but which returns to the rivers as an adult. The islands have 19 species of endemic freshwater invertebrates, including one mollusc, one crustacean, a mayfly, 12 flies and two caddis flies. Auckland Islands cockle are endemic to the islands.

Marine mammals

Only two native mammals exist: two species of seal which haul out on the islands, the New Zealand fur seal and the threatened New Zealand sea lion. Southern elephant seals started to re-colonize on the islands, too.[28]

A well-recovering population in excess of 2,000 southern right whales is found off the islands, and Port Ross area is considered to be the most important and well-established congregating ground for whales in New Zealand waters. Its importance exceeds the Campbell Island ground.[29]

Birds

The islands hold important seabird breeding colonies, among them albatrosses, penguins and several small petrels,[5] with a million pairs of sooty shearwater. Landbirds include red-fronted and yellow-crowned parakeet, New Zealand falcon, tui, bellbirds, pipits and an endemic subspecies of tomtit.

The whole Auckland Island group has been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because of its significance as a breeding site for several species of seabirds as well as the endemic Auckland shag, Auckland teal, Auckland rail, and Auckland snipe. The seabirds include southern rockhopper and yellow-eyed penguins; Antipodean, southern royal, light-mantled and white-capped albatrosses; and white-chinned petrel.[30]

Ecological history

Several introduced species have come to the islands; goats, other useful animals and seed were brought to the islands by Captains Musgrave and Norman 1865, returning to search for castaways;[31] ecologists eliminated or allowed to go extinct cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, possums and rabbits in the 1990s, but feral cats, pigs and mice remain on Auckland Island. The last rabbits on Enderby Island were removed in 1993 through the application of poison, also eradicating mice there.[32]

Curiously, rats have never managed to colonise the islands, in spite of numerous visits and shipwrecks and their ubiquity on other islands.[33] Introduced species affected the native vegetation and bird life, and caused the extinction of the New Zealand merganser, a duck formerly widespread in southern New Zealand, and ultimately confined to the islands.

The New Zealand Department of Conservation plans to remove the last remaining introduced mammals from Auckland Island, making the entire island group pest-free, in what would be one of the largest multi-species eradication plans in the world.[34] This project started in November 2018, with NZ$2m of initial scoping work. The total cost for the eradication could stretch to NZ$40–50 million over 10 years.[35]

List of endemic species

Legal status

The Auckland Islands – as with all of New Zealand's subantarctic islands – is a National Nature Reserve, afforded the highest possible level of protection under New Zealand law. In addition, a marine reserve encompasses all of the Auckland Islands territorial sea and internal waterways.[1]

All of New Zealand's subantarctic islands are managed by the Southland Conservancy of the Department of Conservation (DOC). Expedition party size, length of stay and landing on the islands are kept to a minimum. Entry is by permit only and applicants must undergo thorough pre-expedition quarantine checks.[1]

When Andrew Fagan made a solo voyage there in a 5.4 metres (18 ft) plywood yacht (and nearly added to the shipwreck tally), he described the DOC permitting process thus:

Not just anyone can go to the Auckland Islands. They are now regarded as special environmentally preserved pieces of land, and to be allowed to go there and touch them, you have to be special as well... Not only, me, but the boat as well… I had been directed to Bluff or Dunedin (the choice was mine) to have the bottom of SW inspected by divers to ensure no nasty invasive seaweeds like Undaria were hitching a ride south to set up an environmentally unwanted colony, like the humans had done in 1850.

— Fagan, Andrew (2012). Swirly World Sails South. Auckland, NZ: HarperCollins. p. 91. ISBN 9781869509828.

See also

- Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica

- Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research

- Territorial claims in Antarctica

- New Zealand subantarctic islands

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

- List of islands of New Zealand

- List of islands

- Desert island

References

- West, Carol (May 2005). "New Zealand Subantarctic Islands Research Strategy" (PDF). Department of Conservation. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Data Table – Protected Areas – LINZ Data Service (recorded area 62564 ha)". Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "New Zealand Sub-Antarctic Islands". UNESCO.

- "Map of the Auckland Islands". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Shirihai, H (2002). A Complete Guide to Antarctic Wildlife. Degerby, Finland: Alua Press. ISBN 951-98947-0-5.

- Denison, R.E.; Coombs, D.S. (1977). "Radiometric ages for some rocks from Snares and Auckland Islands, Campbell Plateau". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 34 (1): 23–29. Bibcode:1977E&PSL..34...23D. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(77)90101-7.

- "4. Early human settlement – Subantarctic islands". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Don Macnaughtan. "Mystery Islands of Remote South Polynesia: Bibliography of Prehistoric Settlement on Norfolk Island, the Kermadecs, Lord Howe, and the Auckland Islands". Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- McLaren, F.B. (1948). The Auckland Islands: Their Eventful History. Wellington: A.H and A.W Reed.

- Headland, R.K. (ed.) (2018) Historical Antarctic Sealing Industry, Cambridge, Scott Polar Research Institute, p.166.

- Conon Fraser, The Enderby settlement; Britain's whaling venture on the subantarctic Auckland Islands 1849–1852, Otago University Press, 2014.

- Wilson, James Oakley (1985) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. p. 31. OCLC 154283103.

- Allen, M. F. (1997). Wake of the Invercauld: Shipwrecked in the Sub-Antarctic. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-1688-3.

- Raynal, Francois Edouard (2003). "Wrecked on a Reef or Twenty Months among the Auckland Isles - A facsimile of the text and illustrations of the 1880 edition published by Thomas Nelson & Sons, London, Edinburgh, and New York, with additional commentaries by Christiane Mortelier". Steele Roberts, New Zealand. Retrieved 27 March 2010

- McLintock, A. H., ed. (1966). "General Grant". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Wellington: R. E. Owen, Government Printer. ISBN 9780478184518.

- "Discover the heritage sites in the Auckland Islands". Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Wrecked on the Auckland Islands in 1907".

- "Auckland Islands helicopter pilot recalls violent crash". Stuff. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "Auckland Islands helicopter crash: Survivors reveal sheer panic, then night on island". 26 April 2019. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- "Auckland Islands helicopter trio found alive after wreckage found in Southern Ocean". Stuff. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- Hall, D. O. W. (1951). "The Cape Expedition". Coastwatchers. Wellington: Dept. of Internal Affairs. OCLC 1022254.

- "Data Table – Protected Areas – LINZ Data Service (recorded area 498000 ha)". Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- "Subantarctic islands". doc.govt.nz. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Fox, Michael (2 March 2014). "Birds, seals, penguins protected". Stuff news. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Joseph Dalton Hooker (1844). Flora Antarctica, Volume 1, Parts 1–2, Flora Novae-Zelandiae – The Botany of the Antarctic Voyage of H.M. Discovery Ships Erebus and Terror in the years 1839–1843. London: Reeve Brothers. pp. title pages.

- Campbell, D; Rudge, M (1976). "The case for controlling the distribution of the tree daisy Olearia lyallii Hook. F. in its type locality, Auckland Islands" (PDF). Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society (23): 109–115.

- Department of Conservation (1999) New Zealand's Subantarctic Islands. Reed Books: Auckland ISBN 0-7900-0719-3

- Antonvanhelden (2012). "Our Far South". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- Stewart R.; Todd B. (2001). "A note on observations of southern right whales at Campbell Island, New Zealand" (PDF). Journals of Cetacean Research Management. 2: 117–120. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Auckland Islands". BirdLife International. 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63512609

- Torr, N (2002) "Eradication of rabbits and mice from subantarctic Enderby and Rose Islands" Archived 12 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Turning the tide: the eradication of invasive species (Proceedings of the international conference on eradication of island invasives; Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 27. Veitch, C. R. and Clout, M.N., eds

- Chimera, C.; Coleman, M. C.; Parkes, J. P. (1995). "Diet of feral goats and feral pigs on Auckland Island, New Zealand" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 19 (2): 203–207.

- Nicoll, Dave (17 December 2017). "Department of Conservation Auckland Island eradication project may be largest in world". Stuff. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Nicoll, Dave (16 November 2018). "DOC start field trials for Auckland Islands pest eradication project". Stuff. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

Further reading

- Wise's New Zealand Guide (4th ed.) (1969). Dunedin: H. Wise & Co. (N.Z.) Ltd.

- Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives of New Zealand (1863, Session III Oct–Dec) (A5)

- Island of the Lost: Shipwrecked At the Edge of the World (2007) by Joan Druett – an account of the Grafton and Invercauld wrecks

- Sub Antarctic New Zealand: A Rare Heritage by Neville Peat – the Department of Conservation guide to the islands

- Lost Gold : Ornithology of the subantarctic Auckland Islands. (2020) by Colin Miskelly. Wellington: Te Papa Press. OCLC 1141973732

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Auckland Islands. |

- Auckland Islands Marine Reserve (New Zealand Department of Conservation)

- High Resolution Map

- Murihiku.com

- A Map of the Islands

- Island Information

- Historical Timeline of the Auckland Islands (abandoned website, archived (abandoned website, archived by the Wayback Machine.

- Diary of a 1962–63 biological visit by E. J. Fisher

- 1948 article on Auckland Islands Coleoptera by E. S. Gourlay

- Islas Auckland - El archipiélago de los naufragios (in spanish)