Aral Sea

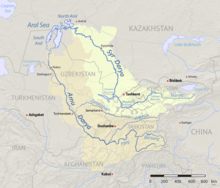

The Aral Sea (Aral /ˈærəl/;[4] Kazakh: Aral teńizi, Арал теңізі, Uzbek: Orol dengizi, Орол денгизи, Karakalpak: Aral ten'izi, Арал теңизи) was an endorheic lake lying between Kazakhstan (Aktobe and Kyzylorda Regions in the north) and Uzbekistan (Karakalpakstan autonomous region in the south). The name roughly translates as "Sea of Islands", referring to over 1,100 islands that had dotted its waters; in the Mongolic languages and Turkic language aral means "island, archipelago". The Aral Sea drainage basin encompasses Uzbekistan and parts of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, and Iran.[1]

| Aral Sea | |

|---|---|

The Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2014 (right) | |

Aral Sea | |

| Location | Kazakhstan - Uzbekistan, Central Asia |

| Coordinates | 45°N 60°E |

| Type | endorheic, natural lake, reservoir (North) |

| Native name | Aral teńizi (Kazakh) Orol dengizi (Uzbek) Аральское море (Russian) |

| Primary inflows | North: Syr Darya South: groundwater only (previously the Amu Darya) |

| Catchment area | 1,549,000 km2 (598,100 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Russia, Afghanistan, Iran[1] |

| Surface area | 68,000 km2 (26,300 sq mi) (1960, one lake) 28,687 km2 (11,076 sq mi) (1998, two lakes) 17,160 km2 (6,626 sq mi) (2004, four lakes) North: 3,300 km2 (1,270 sq mi) (2008) South: 3,500 km2 (1,350 sq mi) (2005) |

| Average depth | North: 8.7 m (29 ft) (2014) South: 14–15 m (46–49 ft) (2005) |

| Max. depth | North: 42 m (138 ft) (2008)[2] 30 m (98 ft) (2003) South: 37–40 m (121–131 ft) (2005) 102 m (335 ft) (1989) |

| Water volume | North: 27 km3 (6 cu mi) (2007) |

| Surface elevation | North: 42 m (138 ft) (2011) South: 29 m (95 ft) (2007) 53.4 m (175 ft) (1960)[3] |

| Settlements | Aral (Kazakhstan), Mo‘ynoq, (Uzbekistan) |

Formerly the fourth largest lake in the world with an area of 68,000 km2 (26,300 sq mi), the Aral Sea has been shrinking since the 1960s after the rivers that fed it were diverted by Soviet irrigation projects. By 1997, it had declined to 10% of its original size, splitting into four lakes: the North Aral Sea, the eastern and western basins of the once far larger South Aral Sea, and one smaller intermediate lake.[5] By 2009, the southeastern lake had disappeared and the southwestern lake had retreated to a thin strip at the western edge of the former southern sea; in subsequent years, occasional water flows have led to the southeastern lake sometimes being replenished to a small degree.[6] Satellite images taken by NASA in August 2014 revealed that for the first time in modern history the eastern basin of the Aral Sea had completely dried up.[7] The eastern basin is now called the Aralkum Desert.

In an ongoing effort in Kazakhstan to save and replenish the North Aral Sea, the Dike Kokaral dam project was completed in 2005; in 2008, the water level in this lake had risen by 12 m (39 ft) compared to 2003.[8] Salinity has dropped, and fish are again present in sufficient numbers for some fishing to be viable.[9] The maximum depth of the North Aral Sea is 42 m (138 ft) (as of 2008).[2]

The shrinking of the Aral Sea has been called "one of the planet's worst environmental disasters".[10] The region's once-prosperous fishing industry has been devastated, bringing unemployment and economic hardship. The water from the diverted Syr Darya river is used to irrigate about two million hectares (5,000,000 acres) of farmland in the Ferghana Valley.[11] The Aral Sea region is also heavily polluted, with consequential serious public health problems. UNESCO added the historical documents concerning the development of the Aral Sea to its Memory of the World Register as a unique resource to study this "environmental tragedy".

Formation

Geographer Nick Middleton believes that the Amu Darya did not flow into the shallow depression that now forms the Aral Sea until the beginning of the Holocene,[12] and it is known that the Amu Darya flowed into the Caspian Sea via the Uzboy channel until the Holocene.[12] The Syr Darya formed a large lake in the Kyzyl Kum during the Pliocene known as the Mynbulak depression.[13]

Ecology

Despite its formerly vast size, the Aral Sea had relatively low indigenous biodiversity. Native fish species of the lake included ship sturgeon (Acipenser nudiventris), all three Pseudoscaphirhynchus sturgeon species, Aral trout (Salmo trutta aralensis), northern pike (Esox lucius), ide (Leuciscus idus oxianus), asp (Aspius aspius iblioides), common rudd (Scardinius erythropthalmus), Turkestan barbel (Luciobarbus capito conocephalus), Aral barbel (L. brachycephalus brachycephalus), common bream (Abramis brama orientalis), white-eyed bream (Ballerus sapa aralensis), Danube bleak (Chalcalburnus chalcoides aralensis), ziege (Pelecus cultratus), crucian carp (Carassius carassius gibelio), common carp (Cyprinus carpio aralensis), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis), Ukrainian stickleback (Pungitius platygaster aralensis), zander (Sander lucioperca), European perch (Perca fluviatilis), and Eurasian ruffe (Gymnocephalus cernuus). All these fish aside from the stickleback lived an anadramous or semi-anadromous lifestyle.[14][15] Following the salinity increase and drying of the lake, the Aral trout, ruffe, Turkestan barbel and all sturgeon species were entirely extirpated and have not since returned due to dams blocking their migration routes, with the Aral trout and Syr Darya sturgeon (Pseudoscaphirhynchus fedtschenkoi) possibly being driven to extinction due to their restricted range.[15][16] All other native fish barring the stickleback (which persisted even during the lake's shrinkage and salinity increase) were also extirpated, but have since returned to the North Aral Sea following its recovery from the 1990s onwards.[14]

Numerous other mostly salt-tolerant fish species were purposefully or inadvertently introduced during the 1960s, due to the increasing salinity of the lake from hydropower and irrigation projects that reduced the flow of fresh water. These include the Baltic herring (Clupea harengus membras), big-scale sand smelt (Atherina boyeri caspia), black-striped pipefish (Syngnatus abaster caspius), Caucasian dwarf goby (Knipowitschia caucasica), monkey goby (Neogobius fluviatilis), round goby (N. melanostomus), Syrman goby (N. syrman), bighead goby (Ponticola kessleri), tubenose goby (Proterorchinus marmoratus), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), bighead carp (H. nobilis), black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) and northern snakehead (Channa argus warpachowski). Prior to the introduction of the herring, sand smelt, and gobies, there were no planktivorous fish in the lake; these introduced species led to a collapse in the lake's population of zooplankton, which also led to a collapse in the population of herring and sand smelt, from which neither species have since recovered.[14] All introduced species aside from the carp, snakehead, and (possibly) pipefish survived the lake's shrinkage and salinity increase, and during this time period the European flounder (Platichthys flesus) was also introduced to the lake to revive fisheries. The extirpated species (aside from possibly the pipefish) returned to the North Aral Sea following its recovery. Herring, sand smelt, gobies, and flounder also managed to persist in the South Aral Sea, but its increasing salinity led all but the gobies to be eventually extirpated from the area.[14]

The decrease in salinity of the North Aral Sea from the 1990s onwards has led to a recovery of its zooplankton population, with many extirpated crustacean and rotifer species returning naturally via the Syr Darya River. The extirpated zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha aralensis) has also been reintroduced to the northern lake. In contrast, only a few invertebrates, mainly nematodes, some rotifers, and parthenogenic brine shrimp, still exist in or have established populations in the South Aral Sea.[14]

History

Most of the area around the Aral Sea was inhabited by desert nomads who left few written records. However, the Oxus delta to the south has a long history under the name of Khwarezm. It was once the westernmost border of China during the Tang dynasty.[17]

The Aral Sea has undergone multiple phases of sea level rise and fall. Climate-driven shifts have contributed to these changes in sea level.[18] To be specific, inflow rates from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya are affected by glacial melt rates at the rivers' headwaters as well as precipitation within the river basins – cold, dry climates restrict both processes.[18] But artificial irrigation systems have also impacted the Aral, beginning in ancient times and continuing to the present.[19][20]

Naval history

Russian naval presence on the Aral Sea started in 1847, with the founding of Raimsk, which was soon renamed Fort Aralsk, near the mouth of the Syr Darya. Soon, the Imperial Russian Navy started deploying its vessels on the sea. Owing to the Aral Sea basin not being connected to other bodies of water, the vessels had to be disassembled in Orenburg on the Ural River, shipped overland to Aralsk (presumably by a camel caravan), and then reassembled. The first two ships, assembled in 1847, were the two-masted schooners named Nikolai and Mikhail. The former was a warship; the latter was a merchant vessel meant to serve the establishment of the fisheries on the great lake. In 1848, these two vessels surveyed the northern part of the sea. In the same year, a larger warship, the Constantine, was assembled. Commanded by Lt. Alexey Butakov (Алексей Бутаков), the Constantine completed the survey of the entire Aral Sea over the next two years.[21] The exiled Ukrainian poet and painter Taras Shevchenko participated in the expedition, and painted a number of sketches of the Aral Sea coast.[22]

For the navigation season of 1851, two newly built steamers arrived from Sweden, again by caravan from Orenburg. As the geological surveys had found no coal deposits in the area, the Military Governor-General of Orenburg Vasily Perovsky ordered "as large as possible supply" of saxaul (Haloxylon ammodendron, a desert shrub, akin to the creosote bush) to be collected in Aralsk for use by the new steamers. Unfortunately, saxaul wood did not turn out a very suitable fuel, and in the later years, the Aral Flotilla was provisioned, at substantial cost, by coal from the Donbass.[21] (This was part of the Russian conquest of Turkestan.)

Irrigation canals

In the early 1960s,[23] the Soviet government decided the two rivers that fed the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya in the south and the Syr Darya in the east, would be diverted to irrigate the desert, in an attempt to grow rice, melons, cereals and cotton.[24] This was part of the Soviet plan for cotton, or "white gold", to become a major export. This temporarily succeeded, and in 1988, Uzbekistan was the world's largest exporter of cotton.[25] Cotton production in Uzbekistan is still important to the national economy of the country.[26][27] It is Uzbekistan's main cash crop, accounting for 17% of its exports in 2006.[28]

Construction of irrigation canals began on a large scale in the 1930s, and was accelerated into a greatly increased scale of construction in the 1960s.[29] Many of the canals were poorly built, allowing water to leak or evaporate. From the Qaraqum Canal, the largest in Central Asia, perhaps 30 to 75% of the water went to waste.[24] In 2012, it was estimated that only 12% of Uzbekistan's irrigation canal length is waterproofed.[29] Of the 47,750 km of interfarm irrigation channels in the basin, only 28% have anti-infiltration linings. Only 77% of farm intakes have flow gauges, and of the 268,500 km of onfarm channels, only 21% have anti-infiltration linings, which retain on average 15% more water than unlined channels.[30]

By 1960, between 20 and 60 km3 (4.8 and 14.4 cu mi) of water each year was going to the land instead of the sea. Most of the sea's water supply had been diverted, and in the 1960s, the Aral Sea began to shrink. From 1961 to 1970, the Aral's level fell at an average of 20 cm (7.9 in) a year; in the 1970s, the average rate nearly tripled to 50–60 cm (20–24 in) per year, and by the 1980s, it continued to drop, now with a mean of 80–90 cm (31–35 in) each year. The rate of water use for irrigation continued to increase; the amount of water taken from the rivers doubled between 1960 and 2000, and cotton production nearly doubled in the same period. In the first half of the 20th century prior to the irrigation, the sea's water level above sea level held steady at 53 m; this has changed drastically by 2010, when the large Aral was 27 m and the small Aral 43 m above sea level.[31]

The disappearance of the lake was no surprise to the Soviets; they expected it to happen long before. As early as 1964, Aleksandr Asarin at the Hydroproject Institute pointed out that the lake was doomed, explaining, "It was part of the five-year plans, approved by the council of ministers and the Politburo. Nobody on a lower level would dare to say a word contradicting those plans, even if it was the fate of the Aral Sea."[32]

The reaction to the predictions varied. Some Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be "nature's error", and a Soviet engineer said in 1968, "it is obvious to everyone that the evaporation of the Aral Sea is inevitable."[33] On the other hand, starting in the 1960s, a large-scale project was proposed to redirect part of the flow of the rivers of the Ob basin to Central Asia over a gigantic canal system. Refilling of the Aral Sea was considered as one of the project's main goals. However, due to its staggering costs and the negative public opinion in Russia proper, the federal authorities abandoned the project by 1986.[34]

From 1960 to 1998, the sea's surface area shrank by about 60%, and its volume by 80%. In 1960, the Aral Sea had been the world's fourth-largest lake, with an area around 68,000 km2 (26,000 sq mi) and a volume of 1,100 km3 (260 cu mi); by 1998, it had dropped to 28,687 km2 (11,076 sq mi) and eighth largest. The salinity of the Aral Sea also increased: by 1990 it was around 376 g/L.[5] (By comparison, the salinity of ordinary seawater is typically around 35 g/L; the Dead Sea's salinity varies between 300 and 350 g/L.)

In 1987, the continuing shrinkage split the lake into two separate bodies of water, the North Aral Sea (the Lesser Sea, or Small Aral Sea) and the South Aral Sea (the Greater Sea, or Large Aral Sea). In June 1991, Uzbekistan gained independence from the Soviet Union. Craig Murray, a UK ambassador to Uzbekistan in 2002, described the independence as a way for Islam Karimov to consolidate his power rather than a move away from a Soviet-style economy and its philosophy of exploitation of the land. Murray attributes the shrinkage of the Aral Sea in the 1990s to Karimov's cotton policy. The government maintained an enormous irrigation system which Murray described as massively wasteful, with most of the water being lost through evaporation before reaching the cotton. Crop rotation was not used, and the depleted soil and monoculture required massive quantities of pesticides and fertilizer. The runoff from the fields washed these chemicals into the shrinking sea, creating severe pollution and health problems. As the water supply of the Aral Sea decreased, the demand for cotton increased and the government reacted by pouring more pesticides and fertilizer onto the land. Murray compared the system to the slavery system in the pre-Civil War United States; forced labor was used, and profits were siphoned off by the powerful and well-connected.[35]

By summer 2003, the South Aral Sea was vanishing faster than predicted. In the deepest parts of the sea, the bottom waters were saltier than the top, and not mixing. Thus, only the top of the sea was heated in the summer, and it evaporated faster than would otherwise be expected. In 2003, the South Aral further divided into eastern and western basins.

In 2004, the Aral Sea's surface area was only 17,160 km2 (6,630 sq mi), 25% of its original size, and a nearly fivefold increase in salinity had killed most of its natural flora and fauna. By 2007, the sea's area had further shrunk to 10% of its original size. The decline of the North Aral has now been partially reversed following construction of a dam (see below), but the remnants of the South Aral continue to disappear and its drastic shrinkage has created the Aralkum, a desert on the former lake bed.

The inflow of groundwater into the South Aral Sea will probably not in itself be able to stop the desiccation, especially without a change in irrigation practices.[36] This inflow of about 4 km3 (0.96 cu mi) per year is larger than previously estimated. The groundwater originates in the Pamirs and Tian Shan Mountains and finds its way through geological layers to a fracture zone[37] at the bottom of the Aral.

The Aral Sea from space, North at bottom, August 1985

The Aral Sea from space, North at bottom, August 1985_NASA_STS085-503-119.jpg) The Aral Sea from space, North at bottom, August 1997

The Aral Sea from space, North at bottom, August 1997 The Aral Sea from space, North at top, August 2009

The Aral Sea from space, North at top, August 2009 The Aral Sea from space, North at top, August 2017

The Aral Sea from space, North at top, August 2017.jpg) April 2018

April 2018

Impact on environment, economy, and public health

The Aral Sea is considered an example of ecosystem collapse.[38] The ecosystems of the Aral Sea and the river deltas feeding into it have been nearly destroyed, not least because of the much higher salinity. The receding sea has left huge plains covered with salt and toxic chemicals resulting from weapons testing, industrial projects, and pesticides and fertilizer runoff. Due to the shrinking water source and subsequent worsening water and soil quality, pesticides were increasingly used starting in the 1960s to increase cotton yields, which further polluted the water with toxins such as DDTs.[39] Furthermore, “PCB-compounds and heavy metals” from industrial pollution contaminated both water and soil.[40] Due to the minimal amount of water left in the Aral sea, concentrations of these pollutants have increased drastically in both the water and soil. These substances form wind-borne toxic dust that spreads throughout the region. People living near the Aral Sea come in contact with pollutants through drinking water and inhalation of contaminated dust.[41] Furthermore, due to the presence in drinking water, the toxins have entered the food chain.[40] As a result, the land around the Aral Sea is heavily polluted, and the people living in the area are suffering from a lack of fresh water and health problems, including high rates of certain forms of cancer and lung diseases. Respiratory illnesses, including tuberculosis (most of which is drug resistant) and cancer, digestive disorders, anaemia, and infectious diseases are common ailments in the region. Liver, kidney, and eye problems can also be attributed to the toxic dust storms. All of this has resulted in an unusually high fatality rate among vulnerable parts of the population: the child mortality rate is 75 in every 1,000 newborns, and maternity death is 12 in every 1,000 women.[42][43]

The dust storms also contribute to water shortages through salt deposition.[37] The overuse of pesticides on crops to preserve yields has made this worse, with pesticide use far beyond health limits.[37] Crops in the region are destroyed by salt being deposited onto the land, and fields are being flushed with water at least four times per day to try to remove the salinity from the soils.[37] The land is decaying, causing few crops to grow besides fodder, which is what the farmers in Kazakhstan are now deciding to seed.[44] Large bodies of water, like the Aral Sea, can moderate a region's climate by altering moisture and energy balance.[45] Loss of water in Aral Sea has changed surface temperatures and wind patterns. This has resulted in hotter summers and cooler winters (an estimated 2˚C-6˚C change in either direction) and the emergence of dust storms over the area.[45]

Biology

The Aral Sea fishing industry, which in its heyday employed some 40,000 and reportedly produced one-sixth of the Soviet Union's entire fish catch, has been devastated. In the 1980s commercial harvests were becoming unsustainable, and by 1987 commercial harvest became nonexistent. Due to the declining sea levels, salinity levels became too high for the 20 native fish species to survive. The only fish that could survive the high-salinity levels was flounder. Due to the declining sea levels, former fishing towns along the original shores have become ship graveyards.[46] Aral, originally the main fishing port, is now several kilometres from the sea and has seen its population decline dramatically since the beginning of the crisis.[47] The town of Moynaq in Uzbekistan had a thriving harbour and fishing industry that employed about 30,000 people;[48] now it lies kilometres from the shore. Fishing boats lie scattered on the dry land that was once covered by water; many have been there for 20 years.

The South Aral Sea remains too saline to host any species other than halotolerant organisms.[49] The South Aral has been incapable of supporting fish since the late 1990s, when the flounder were killed by rising salinity levels.[50]

Also destroyed is the muskrat-trapping industry in the deltas of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, which used to yield as many as 500,000 pelts a year.[32]

Aral Sea dust storm, March 2010

Aral Sea dust storm, March 2010 Abandoned ship near Aral, Kazakhstan

Abandoned ship near Aral, Kazakhstan A former harbour in the city of Aral

A former harbour in the city of Aral Local Kazakh fisherman harvesting the day's catch

Local Kazakh fisherman harvesting the day's catch

Vulnerable populations

Women and children are the most vulnerable populations in this environmental health crisis due to the highly polluted and salinated water used for drinking and the dried seabed.[51] Toxins from pesticides have been found in blood and breast milk of mothers, specifically organochlorides, polychlorinated biphenyl compounds (PCBs), DDT compounds, and TCDD.[52][40] These toxins can be, and often are, passed on to the children of these mothers resulting in low birthweight children and children with abnormalities. The rate of infants being born with abnormalities is five times higher in this region than in European countries.[53] The Aral Sea region has 26% of its children born at low birthweight, which is two standard deviations away from a national study population gathered by the WHO.[54] Exposures to toxic chemicals from the dry seabed and polluted water have caused other health issues in women in children. Renal tubular dysfunction has become a large health concern in children in the Aral Sea region as it is showing extremely high prevalence rates. Renal tubular dysfunction can also be related to growth and developmental stunting.[55] This, in conjunction with the already high rate of low birth weight children and children born with abnormalities, poses severe negative health effects and outcomes on children. These issues are compounded by the lack of research of maternal and child health effects caused by the demise of the Aral Sea. For example, only 26 English-language peer-reviewed articles and four reports on children's health were produced between 1994 and 2008.[56] In addition, there is a lack of health infrastructure and resources in the Aral Sea region to combat the health issues that have arisen.[57]

There is a lack of medication and equipment in many medical facilities, so health professionals do not have access to the necessary supplies to do their jobs in the Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan regions.[58] There is also meager development of a health information system that would allow for extensive research or surveillance of emerging health issues due to Aral sea issues.[58] An absence of a primary care approach in the health systems of this region also hinders services and access that could prevent and treat issues stemming from the Aral Sea crisis, especially in women and children.[58]

The impoverished are also particularly vulnerable to the environmental and health related effects of changes to the Aral Sea. These populations were most likely to reside downstream from the Basin and in former coastal communities.[59] They were also among the first to be detrimentally affected, representing at least 4.4 million people in the region.[60] Considered to have the worst health in this region, their plight was not helped when their fishery livelihoods vanished with the decreasing levels of water and loss of many aquatic species.[61] Thus, those in poverty are entrenched in a vicious cycle.

Solution

Possible environmental solutions

Many different solutions to the problems have been suggested over the years, varying in feasibility and cost, including:

- Improving the quality of irrigation canals

- Using alternative cotton species that require less water[62]

- Promoting non-agricultural economic development in upstream countries[63]

- Using fewer chemicals on the cotton

- Cultivating crops other than cotton

- Redirecting water from the Volga, Ob and Irtysh rivers to restore the Aral Sea to its former size in 20–30 years at a cost of US$30–50 billion[64]

- Pumping sea water into the Aral Sea from the Caspian Sea via a pipeline, and diluting it with fresh water from local catchment areas[65]

-03.jpg)

In January 1994, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan signed a deal to pledge 1% of their budgets to help the sea recover.

In March 2000, UNESCO presented their "Water-related vision for the Aral Sea basin for the year 2025"[66] at the second World Water Forum in The Hague. This document was criticized for setting unrealistic goals and for giving insufficient attention to the interests of the area immediately around the former lakesite, implicitly giving up on the Aral Sea and the people living on the Uzbek side of the lake.[67]

By 2006, the World Bank's restoration projects, especially in the North Aral, were giving rise to some unexpected, tentative relief in what had been an extremely pessimistic picture.[68]

Aral Sea Basin Programme - 1

The future of the Aral Sea and the responsibility for its survival are now in the hands of the five countries: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan. In 1994, they adopted the Aral Sea Basin Programme.[69] The Programme's four objectives are:

- To stabilize the environment of the Aral Sea Basin

- To rehabilitate the disaster area around the sea

- To improve the management of the international waters of the Aral Sea Basin

- To build the capacity of institutions at the regional and national level to advance the programme's aims

ASBP: Phase One

The first phase of the plan effectively began with the first involvement from the World Bank in 1992, and was in operation until 1997. It was ineffectual for a number of reasons, but mainly because it was focused on improving directly the land around the Aral Sea, whilst not intervening in the water usage upstream. There was considerable concern amongst the Central Asian governments, which realised the importance of the Aral Sea in the ecosystem and the economy of Central Asia, and they were prepared to cooperate, but they found it difficult to implement the procedures of the plan.

This is due in part to a lack of co-operation among the affected people. The water flowing into the Aral Sea has long been considered an important commodity, and trade agreements have been made to supply the downstream communities with water in the spring and summer months for irrigation. In return, they supply the upstream countries with fuel during the winter, instead of storing water during the warm months for hydroelectric purposes in winter. However, very few legal obligations are binding these contracts, particularly on an international stage.

ASBP: Phase Two

Phase Two of the Aral Sea Basin programme followed in 1998 and ran for five years. The main shortcomings of phase two were due to its lack of integration with the local communities involved. The scheme was drawn up by the World Bank, government representatives, and various technical experts, without consulting those who would be affected. An example of this was the public awareness initiatives, which were seen as propagandist attempts by people with little care or understanding of their situation. These failures have led to the introduction of a new plan, funded by a number of institutions, including the five countries involved and the World Bank.

ASBP: Phase Three

In 1997, a new plan was conceived which would continue with the previous restoration efforts of the Aral Sea. The main aims of this phase are to improve the irrigation systems currently in place, whilst targeting water management at a local level. The largest project in this phase is the North Aral Sea Project, a direct effort to recover the northern region of the Aral Sea. The North Aral Sea Project's main initiative is the construction of a dam across the Berg Strait, a deep channel which connects the North Aral Sea to the South Aral Sea. The Kok-Aral Dam is 13 kilometres (8 miles) long and has capacity for over 29 cubic kilometres of water to be stored in the North Aral Sea, whilst allowing excess to overflow into the South Aral Sea.

Aral Sea Basin Programme - 2

On 6 October 2002, the Heads of States met again to revise the ASBP program. ASBP-2 was in place from 2003 to 2010. The main purpose of the ASBP-2 was to set up projects that covered a vast amount of environmental, socioeconomic and water management issues. The ASBP-2 was financed by organization such as the UNDP, World Bank, USAID, Asian Development Bank, and the governments of Switzerland, Japan, Finland, Norway and others. Over 2 billion US Dollars was provided by the IFAS country members to the program.[70]

Aral Sea Basin Programme - 3

On 28 April 2009 the Head of States came together with the Interstate commission for Water Coordination, Interstate Commission for Sustainable Development and National Experts and donors to develop the ASBP-3. This Program was in effect from 2011- 2015. The main purpose of the ASBP-3 was to improve the environmental and socio-economic situation of the Aral Sea Basin. The four program prioritizes were:[71]

- Direction one: Integrated Use of Water Resources

- Direction two: Environmental protection

- Direction three: Socio-economic Development

- Direction four: Improving the institutional and legal instruments

ASBP-3: Direction One

Direction One's main purpose is to propose program that focus on addressing transboundary water resources management, establishment of monitoring systems and addressing safety concerns in water facilities. Examples of programs that have been proposed include:[72]

- “Developing proposals to optimize the management and use of water resources in Central Asia, taking into account environmental factors, effects of climate change to meet the national interests of the Aral Sea basin.”

- “Improving the quality of hydrometeorological services for weather-dependent sectors of the economy of Central Asia.”

- “Creating a database and computer models for the management of transboundary water resources.”

- “Assisting the countries in reducing the risk of natural disasters, including through the strengthening of regional cooperation, improve disaster preparedness and response.”

ASBP-3: Direction Two

Directions two's main focus is on addressing the issues related to environmental protection and improvement of the environment. Areas of interest include:[73]

- “The environment in the deltas of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya improved.”

- “Mountain environments improved.”

- “The environment and productivity of pastures improved.”

- “A regional information system on the environment established.”

ASBP-3: Direction Three

Direction three looks to address socio-economic issues by focusing on education and public health, improving unemployment rates, improving water systems, increasing sustainable development and improving living conditions. The expected outputs are:[74]

- “An improved access to safe drinking water.”

- “For the rural population: establishment and/or development of private small enterprises, creation of new jobs, and increased labor efficiency.”

- “An improvement in the quality of medical services”

- “An improvement in the effectiveness and quality of education in schools and pre-school facilities in rural areas.”

ASBP-3: Direction Four

Direction Four aims to address issues related to institutional development and the development of policies and strategies that relate to sustainable development and public awareness. Expected outputs include:[75]

- “Conditions for a transparent and mutually beneficial regional dialogue and cooperation, including setting up a sectorial dialogue between governments established.”

- “A Prototype of the single information and analysis system for the water sector established.”

- “A Communication Strategy for stakeholders and the public established.”

- “Training systems for the water sector and the hydrometeorological services in Central Asia improved.”

North Aral Sea restoration work

Work is being done to restore in part the North Aral Sea. Irrigation works on the Syr Darya have been repaired and improved to increase its water flow, and in October 2003, the Kazakh government announced a plan to build Dike Kokaral, a concrete dam separating the two halves of the Aral Sea. Work on this dam was completed in August 2005; since then, the water level of the North Aral has risen, and its salinity has decreased. As of 2006, some recovery of sea level has been recorded, sooner than expected.[76] "The dam has caused the small Aral's sea level to rise swiftly to 38 m (125 ft), from a low of less than 30 m (98 ft), with 42 m (138 ft) considered the level of viability."[77]

Economically significant stocks of fish have returned, and observers who had written off the North Aral Sea as an environmental disaster were surprised by unexpected reports that, in 2006, its returning waters were already partly reviving the fishing industry and producing catches for export as far as Ukraine. The improvements to the fishing industry were largely due to the drop in the average salinity of the sea from 30 grams to 8 grams per liter; this drop in salinity prompted the return of almost 24 freshwater species.[46] The restoration also reportedly gave rise to long-absent rain clouds and possible microclimate changes, bringing tentative hope to an agricultural sector swallowed by a regional dustbowl, and some expansion of the shrunken sea.[78]

"The sea, which had receded almost 100 km (62 mi) south of the port-city of Aralsk, is now a mere 25 km (16 mi) away." The Kazakh Foreign Ministry stated that "The North Aral Sea's surface increased from 2,550 square kilometers (980 sq mi) in 2003 to 3,300 square kilometers (1,300 sq mi) in 2008. The sea's depth increased from 30 meters (98 ft) in 2003 to 42 meters (138 ft) in 2008."[2] Now, a second dam is to be built based on a World Bank loan to Kazakhstan, with the start of construction initially slated for 2009 and postponed to 2011, to further expand the shrunken Northern Aral,[79] eventually reducing the distance to Aralsk to only 6 km (3.7 mi). Then, it was planned to build a canal spanning the last 6 km, to reconnect the withered former port of Aralsk to the sea.[80]

Future of South Aral Sea

The South Aral Sea, half of which lies in Uzbekistan, was abandoned to its fate. Most of Uzbekistan's part of the Aral Sea is completely shriveled up. Only excess water from the North Aral Sea is periodically allowed to flow into the largely dried-up South Aral Sea through a sluice in the dyke.[81] Discussions had been held on recreating a channel between the somewhat improved North and the desiccated South, along with uncertain wetland restoration plans throughout the region, but political will is lacking.[76] Unlike Kazakhstan, which has partially revived its part of the Aral Sea, Uzbekistan shows no signs in abandoning the Amu Darya river to irrigate their cotton, and is moving toward oil exploration in the drying South Aral seabed.[80]

Attempts to mitigate the effects of desertification include planting vegetation in the newly exposed seabed; however, intermittent flooding of the eastern basin is likely to prove problematic for any development. Redirecting what little flow there is from the Amu Darya to the western basin may salvage fisheries there while relieving the flooding of the eastern basin.[82]

Institutional bodies

The Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia (ICWC) was formed on 18 February 1992 to formally unite Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in the hopes of solving environmental, as well as socioeconomic problems in the Aral Sea region. The River Basin Organizations (the BVOs) of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers were institutions called upon by the ICWC to help manage water resources. According to the ICWC,[83] the main objectives of the body are:

- River basin management

- Water allocation without conflict

- Organization of water conservation on transboundary water courses

- Interaction with hydrometeorological services of the countries on flow forecast and account

- Introduction of automation into head structures

- Regular work on ICWC and its bodies' activity advancement

- Interstate agreements preparation

- International relations

- Scientific research

- Training

The International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS) was developed on 23 March 1993, by the ICWC to raise funds for the projects under Aral Sea Basin programmes. The IFAS was meant to finance programmes to save the sea and improve on environmental issues associated with the basin's drying. This programme has had some success with joint summits of the countries involved and finding funding from the World Bank to implement projects; however, it faces many challenges, such as enforcement and slowing progress.[84]

Vozrozhdeniya

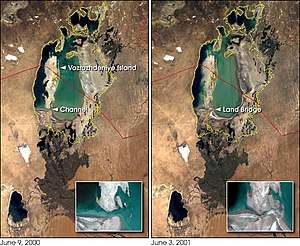

Vozrozhdeniya (Rebirth) Island is a former island of the Aral Sea or South Aral Sea. Due to the ongoing shrinkage of the Aral, it became first a peninsula in mid-2001 and finally part of the mainland.[85] Other islands like Kokaral and Barsa-Kelmes shared a similar fate. Since the disappearance of the Southeast Aral in 2008, Vozrozhdeniya effectively no longer exists as a distinct geographical feature. The area is now shared by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

In 1948, a top-secret Soviet bioweapons laboratory was established on the island, in the centre of the Aral Sea which is now disputed territory between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The exact history, functions and current status of this facility are still unclear, but bio-agents tested there included Bacillus anthracis, Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, Brucella suis, Rickettsia prowazekii, Variola major (smallpox), Yersinia pestis, botulinum toxin, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.[86] In 1971, weaponized smallpox from the island reached a nearby ship, which then allowed the virus to spread to the city of Aral. Ten people there were infected, of whom three died, and a massive vaccination effort involving 50,000 inhabitants ensued (see Aral smallpox incident). The bioweapons base was abandoned in 1992 following the disintegration of the Soviet Union the previous year. Scientific expeditions proved this had been a site for production, testing and later dumping of pathogenic weapons. In 2002, through a project organized by the United States and with Uzbekistan's assistance, 10 anthrax burial sites were decontaminated. According to the Kazakh Scientific Center for Quarantine and Zoonotic Infections, all burial sites of anthrax were decontaminated.[87]

Oil and gas exploration

Ergash Shaismatov, the deputy prime minister of Uzbekistan, announced on 30 August 2006, that the Uzbek government and an international consortium consisting of state-run Uzbekneftegaz, LUKoil Overseas, Petronas, Korea National Oil Corporation, and China National Petroleum Corporation signed a production-sharing agreement to explore and develop oil and gas fields in the Aral Sea, saying, "The Aral Sea is largely unknown, but it holds a lot of promise in terms of finding oil and gas. There is risk, of course, but we believe in the success of this unique project." The consortium was created in September 2005.[88]

As of 1 June 2010, 500,000 cubic meters of gas had been extracted from the region at a depth of 3 km.[89]

Films

The plight of the Aral coast was portrayed in the 1989 film Psy ("Dogs") by Soviet director Dmitri Svetozarov.[90] The film was shot on location in an actual ghost town located near the Aral Sea, showing scenes of abandoned buildings and scattered vessels.

In 2000, the MirrorMundo foundation produced a documentary film called Delta Blues about the problems arising from the drying up of the sea.[91]

In June 2007, BBC World broadcast a documentary called Back From the Brink? made by Borna Alikhani and Guy Creasey, which showed some of the changes in the region since the introduction of the Aklak Dam.

Bakhtyar Khudojnazarov's 2012 movie Waiting for the Sea deals with the impacts on people's life in a fishing town at the shore of the Aral Sea.

In 2012 Christoph Pasour and Alfred Diebold produced an 85-minute film with the title "From the glaciers to the Aral Sea", which shows the water management system in the Aral Sea basin and in particular the situation around the Aral Sea. The film was first screened at the 6th World Water Forum in Marseille, France, in 2012 and is now available on the website: www.waterunites-ca.org[92] and on Alfred Diebold's YouTube channel: waterunitesca.[93]

In October 2013, Al Jazeera produced a documentary film called People of The Lake, directed by Ensar Altay, describing the current situation.[94]

In 2014, director Po Powell shot much of the footage for the Pink Floyd single "Louder than Words" video near the remains of the Aral Sea on the border between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.[95]

In October 2018, the BBC produced a programme called Fashion's Dirty Secrets, a large part of which shows the extent of the shrinking Aral and its consequences, together with maybe a little glimmer of hope.[96]

See also

- List of drying lakes

- Dead Sea

- Draining of the Mesopotamian marshes – a similar water diversion project in Iraq

- Lake Chad

- Salton Sea

- Sistan Basin – a large wetland ecosystem in Afghanistan and Iran on the verge of collapse

- Sudd – a large marshland in Africa, site of another planned large-scale draining project

- Tulare Lake – California's largest lake, drained between 1880 and 1970

References

- "DRAINAGE BASIN OF THE ARAL SEA AND OTHER TRANSBOUNDARY SURFACE WATERS IN CENTRAL ASIA" (PDF). United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). 2005. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "The Kazakh Miracle: Recovery of the North Aral Sea". Environment News Service. 1 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- JAXA - South Aral Sea shrinking but North Aral Sea expanding

- "Aral Sea | Definition of Aral Sea in English by Lexico Dictionaries".

- Philip Micklin; Nikolay V. Aladin (March 2008). "Reclaiming the Aral Sea". Scientific American. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Satellite image, August 16, 2009 (click on "2009" and later links)". 24 September 2014.

- Liston, Enjoli (1 October 2014). "Satellite images show Aral Sea basin 'completely dried'". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Stephen M Bland. "Central Asia Caucasus". stephenmbland.com.

- "Aral Sea Reborn". Al Jazeera. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Daily Telegraph (5 April 2010). "Aral Sea 'one of the planet's worst environmental disasters'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "Syr Darya river, Central Asia". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Middleton, Nick; "The Aral Sea" in Shahgedanova Maria; The Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia; pp. 497-498

- Velichko, Andrey and Spasskaya, Irina; "Climatic Change and the Development of Landscapes" in Shahgedanova Maria; The Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia; pp. 48-50

- Aladin, Nikolay Vasilevich; Gontar, Valentina Ivanovna; Zhakova, Ljubov Vasilevna; Plotnikov, Igor Svetozarovich; Smurov, Alexey Olegovich; Rzymski, Piotr; Klimaszyk, Piotr (2019). "The zoocenosis of the Aral Sea: six decades of fast-paced change". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 26 (3): 2228–2237. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3807-z. ISSN 0944-1344. PMC 6338704. PMID 30484051.

- Nedoluzhko, Artem V.; Sharko, Fedor S.; Tsygankova, Svetlana V.; Boulygina, Eugenia S.; Barmintseva, Anna E.; Krasivskaya, Anna A.; Ibragimova, Amina S.; Gruzdeva, Natalia M.; Rastorguev, Sergey M.; Mugue, Nikolai S. (20 January 2020). "Molecular phylogeny of one extinct and two critically endangered Central Asian sturgeon species (genus Pseudoscaphirhynchus ) based on their mitochondrial genomes". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57581-y. ISSN 2045-2322.

- "The Red List of Kazakhstan ::: Aral trout (Salmo trutta aralensis)". www.redbookkz.info. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Gan, Chunsong (2019). A Concise Reader of Chinese Culture. ISBN 9789811388675.

- Cretaux et. al 2013, pp. 100, 105-106

- Cretaux et. al 2013, pp. 103

- Boroffka 2010, pp. 295

- Valikhanov, Chokan Chingisovich; Venyukov, Mikhail Ivanovich (1865). The Russians in Central Asia: their occupation of the Kirghiz steppe and the line of the Syr-Daria: their political relations with Khiva, Bokhara, and Kokan: also descriptions of Chinese Turkestan and Dzungaria. Translated by John Michell, Robert Michell. London: Edward Stanford. pp. 324–329.

- Rich, David Alan (1998). The Tsar's colonels: professionalism, strategy, and subversion in late Imperial Russia. Harvard University Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-674-91111-3.

- "Soviet cotton threatens a region's sea - and its children". New Scientist. 18 November 1989. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- Ryszard Kapuscinski, Imperium, 2019, pp.255-260.

- USDA-Foreign Agriculture Service (2013). "Cotton Production Ranking". National Cotton Council of America. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- "Cotton production linked to images of the dried up Aral Sea basin". The Guardian. 1 October 2014.

- "The True Costs of Cotton: Cotton Production and Water Insecurity" (PDF). Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF).

- Uzbekistan in Numbers 2006, State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 2007 (in Russian).

- Simon N. Gosling, Sustainability - The Geography Perspective, University of Nottingham, 2012

- "ca-water.net, a knowledge base for projects in the Central Asia". 2003. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Micklin, Philip (December 2017). "The past, present, and future Aral Sea". Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management. 15 (3): 193–213. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1770.2010.00437.x.

- Michael Wines (9 December 2002). "Grand Soviet Scheme for Sharing Water in Central Asia Is Foundering". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Bissell, Tom (2002). Eternal Winter: Lessons of the Aral Sea Disaster. Harper's. pp. 41–56.

- Glantz, Michael H. (1999). Creeping Environmental Problems and Sustainable Development in the Aral Sea... Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-521-62086-4. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Craig Murray (2007). Dirty Diplomacy. Scribner.

- Philip P. Micklin (1988). "Desiccation of the Aral Sea". CIESIN, Columbia University. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "The Aral Sea Crisis". Thompson, Columbia University. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Keith, DA; Rodríguez, J.P.; Rodríguez-Clark, K.M.; Aapala, K.; Alonso, A.; Asmussen, M.; Bachman, S.; Bassett, A.; Barrow, E.G.; Benson, J.S.; Bishop, M.J.; Bonifacio, R.; Brooks, T.M.; Burgman, M.A.; Comer, P.; Comín, F.A.; Essl, F.; Faber-Langendoen, D.; Fairweather, P.G.; Holdaway, R.J.; Jennings, M.; Kingsford, R.T.; Lester, R.E.; Mac Nally, R.; McCarthy, M.A.; Moat, J.; Nicholson, E.; Oliveira-Miranda, M.A.; Pisanu, P.; Poulin, B.; Riecken, U.; Spalding, M.D.; Zambrano-Martínez, S. (2013). "Scientific Foundations for an IUCN Red List of Ecosystems". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e62111. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862111K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062111. PMC 3648534. PMID 23667454. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Whish-Wilson, Phillip (2002). "The Aral Sea environmental health crisis" (PDF). Journal of Rural and Remote Environmental Health. 1 (2): 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Jensen, S.; Mozhitova, Z.; Zetterstrom, R. (5 November 1997). "Environmental pollution and child health in the Aral Sea region in Kazakhstan". Science of the Total Environment. 206 (2–3): 187–193. Bibcode:1997ScTEn.206..187J. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(97)00225-8.

- O'Hara, Sarah; Wiggs, Giles; Mamedov, Batyr; Davidson, George; Hubbard, Richard (19 February 2000). "Exposure to airborne dust contaminated with pesticide in the Aral Sea region". The Lancet. 355 (9204): 627–628. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04753-4. PMID 10696990.

- "Aral Sea - Aral Sea". Archived from the original on 16 March 2009.

- Mętrak M. Health and social consequences of the Aral Lake disaster. In: Chwil M., Skoczylas M.M. (red.). Contemporary research on the state of the environment and the medicinal use of plants. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Przyrodniczego w Lublinie, pp. 99-108. Accessible in: https://wydawnictwo.up.lublin.pl/e-ksiazka

- Saiko, Tatyana (1998). "Geographical and socio-economic dimensions of the Aral Sea crisis and their impact on the potential for community action". Journal of Arid Environments. 39 (2): 230. Bibcode:1998JArEn..39..225S. doi:10.1006/jare.1998.0406.

- McDermid, Sonali Shukla; Winter, Jonathan (December 2017). "Anthropogenic forcings on the climate of the Aral Sea: A regional modeling perspective". Anthropocene. 20: 48–60. doi:10.1016/j.ancene.2017.03.003.

- Chen, Dene-Hern (16 March 2018). "Once Written Off for Dead, the Aral Sea Is Now Full of Life".

- Bland, Stephen M. (27 January 2015). "Kazakhstan: Measuring the Northern Aral's Comeback". EurasiaNet. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Uzbekistan: Moynaq village faces the Aral Sea disaster". UNICEF.

- Aladin et al. 2018, p. 2234.

- Ermakhanov et al. 2012, p. 7.

- Ataniyazova, Oral (18 March 2003). "Health and Ecological Consequences of the Aral Sea Crisis" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Whish-Wilson, Phillip (2002). "The Aral Sea environmental health crisis" (PDF). Journal of Rural and Remote Environmental Health. 1 (2): 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Ataniyazova, Oral (18 March 2003). "Health and Ecological Consequences of the Aral Sea Crisis" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Crighton, Eric James; Barwin, Lynn; Small, Ian; Upshur, Ross (April 2011). "What have we learned? A review of the literature on children's health and the environment in the Aral Sea area". International Journal of Public Health. 56 (2): 125–138. doi:10.1007/s00038-010-0201-0. PMC 3066395. PMID 20976516.

- Kaneko, K; Chiba, M; Hashizume, M; Kunii, O; Sasaki, S; Shimoda, T; Yamashiro, Y; Caypil, W; Dauletbaev, D (4 March 2003). "Renal tubular dysfunction in children living in the Aral Sea Region". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 88 (11): 966–968. doi:10.1136/adc.88.11.966. PMC 1719339. PMID 14612357.

- Crighton, Eric James; Barwin, Lynn; Small, Ian; Upshur, Ross (April 2011). "What have we learned? A review of the literature on children's health and the environment in the Aral Sea area". International Journal of Public Health. 56 (2): 125–138. doi:10.1007/s00038-010-0201-0. PMC 3066395. PMID 20976516.

- Small, Ian; van der Meer, J; Upshur, Ross (1 June 2001). "Acting on an environmental health disaster: the case of the Aral Sea". Environmental Health Perspectives. 109 (6): 547–549. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109547. PMC 1240333. PMID 11445505.

- Small, Ian; van der Meer, J; Upshur, Ross (1 June 2001). "Acting on an environmental health disaster: the case of the Aral Sea". Environmental Health Perspectives. 109 (6): 547–549. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109547. PMC 1240333. PMID 11445505.

- Peachey, Everett (2004). "The Aral Sea Basin Crisis and Sustainable Water Resource Management in Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Public and International Affairs. 15: 1–20.

- Peachey, Everett (2004). "The Aral Sea Basin Crisis and Sustainable Water Resource Management in Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Public and International Affairs. 15: 1–20.

- Peachey, Everett (2004). "The Aral Sea Basin Crisis and Sustainable Water Resource Management in Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Public and International Affairs. 15: 1–20.

- Usmanova, RM (25 March 2013). "Aral Sea and sustainable development". Water Sci Technol. 47 (7–8): 41–7. doi:10.2166/wst.2003.0669. PMID 12793660.

- Olli Varis (2 October 2014). "Resources: Curb vast water use in central Asia. [Nature Vol 514(7520)]". Nature News. 514 (7520): 27–9. doi:10.1038/514027a. PMID 25279902.

- Ed Ring (27 September 2004). "Release the Rivers: Let the Volga & Ob Refill the Aral Sea". Ecoworld. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Aral Sea Refill: Seawater Importation Macroproject". The Internet Encyclopedia of Science. 29 June 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- "Water-related vision for the Aral Sea basin for the year 2025" (PDF) (in English and Russian). UNESCO. March 2000. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "(Nederland) - UNESCO promotes unsustainable development in Central Asia". Indymedia NL. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "A Witch's Brew". BBC News. July 2006. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Shawki Barghouti (2006). Case Study of the Aral Sea Water and Environmental Management Project: an independent evaluation of the World Bank's support of regional programmes. The World Bank (Report). Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Program of actions on providing assistance to the countries of the Aral Sea Basin for the period of 2011-2015 (ASBP-3) (PDF) (Report). International Fund for saving the Aral Sea. 2012.

- Program of actions on providing assistance to the countries of the Aral Sea Basin for the period of 2011-2015 (ASBP-3) (PDF) (Report). International Fund for saving the Aral Sea. 2012.

- Program of actions on providing assistance to the countries of the Aral Sea Basin for the period of 2011-2015 (ASBP-3) (PDF) (Report). International Fund for saving the Aral Sea. 2012.

- Program of actions on providing assistance to the countries of the Aral Sea Basin for the period of 2011-2015 (ASBP-3) (PDF) (Report). International Fund for saving the Aral Sea. 2012.

- Program of actions on providing assistance to the countries of the Aral Sea Basin for the period of 2011-2015 (ASBP-3) (PDF) (Report). International Fund for saving the Aral Sea. 2012.

- Program of actions on providing assistance to the countries of the Aral Sea Basin for the period of 2011-2015 (ASBP-3) (PDF) (Report). International Fund for saving the Aral Sea. 2012.

- Ilan Greenberg (7 April 2006). "A vanished Sea Reclaims its form in Central Asia". Int. Her. Trib. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Ilan Greenberg (6 April 2006). "As a Sea Rises, So Do Hopes for Fish, Jobs and Riches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- "Miraculous Catch in Kazakhstan's Northern Aral Sea". The World Bank. June 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "North Aral Sea Recovery". The Earth Observatory. NASA. 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Martin Fletcher (23 June 2007). "The return of the sea". The Times. London. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Saving a Corner of the Aral Sea". The World Bank. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "The rehabilitation of the ecosystem and bioproductivity of the Aral Sea under conditions of water scarcity" (PDF). August 2007.

- "Strategies suggested for implementation". ICWC. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "IFAS". WaterWiki.net. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- NASA Visible Earth - "Rebirth" Island Joins the Mainland Archived 28 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Aral Sea Archived 28 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Bozheyeva, G., Y. Kunakbayev and D. Yeleukenov (1999). Former Soviet Biological Weapons Facilities in Kazakhstan: Past, Present and Future. Occasional Paper 1. Monterey, Calif.: Monterey Institute of International Studies, Center for Nonproliferation Studies.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Khabar Television/BBC Monitoring (20 November 2002). "Kazakhstan: Vozrozhdeniya Anthrax Burial Sites Destroyed". Global Security Newswire. Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Uzbekistan, intl consortium ink deal on exploring Aral Sea". ITAR-Tass. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010.

- Michael Hancock-Parmer (9 June 2010). "Aral Gas". Registan.net. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010.

- "Psy". Kino Expert. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- "Delta Blues (in a land of cotton)". YouTube. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- "Videos - From the Glaciers to the Aral Sea - Water Unites". www.waterunites-ca.org.

- "Water Unites - From the Glaciers to the Aral Sea". youtube.

- Al Jazeera World. "People of the Lake". Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "Watch Pink Floyd's Surreal, Sun-Baked 'Louder Than Words' Video". Rolling Stone. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Stacey Dooley Investigates: Are your clothes wrecking the planet? Radhika Sanghani, 9 October 2018, BBC

Sources

- Aladin, Nikolay Vasilevich; Gontar, Valentina Ivanovna; Zhakova, Ljubov Vasilevna; Plotnikov, Igor Svetozarovich; Smurov, Alexey Olegovich; Rzymski, Piotr; Klimaszyk, Piotr (27 November 2018). "The zoocenosis of the Aral Sea: six decades of fast-paced change". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 26 (3): 2228–2237. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-3807-z. PMC 6338704. PMID 30484051.

- Bissell, Tom (April 2002). "Eternal Winter: Lessons of the Aral Sea Disaster". Harper's. pp. 41–56. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Bissell, Tom (2004). Chasing The Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-72754-2.

- Borroffka, Nikolaus G.O. (2010), "Archaeology and Its Relevance to Climate and Water Level Changes: A Review", in Kostianoy, Andrey G.; Kosarev, Aleksey N. (eds.), The Aral Sea Environment, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, pp. 283–303

- Cretaux, Jean-François; Letolle, René; Bergé-Nguyen, Muriel (2013). "History of Aral Sea level variability and current scientific debates". Global and Planetary Change. 110: 99–113. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Ellis, William S (February 1990). "A Soviet Sea Lies Dying". National Geographic. pp. 73–93.

- Ermakhanov, Zaualkhan K.; Plotnikov, Igor S.; Aladin, Nikolay V.; Micklin, Philip (28 February 2012). "Changes in the Aral Sea ichthyofauna and fishery during the period of ecological crisis". Lakes & Reservoirs: Research and Management. 17 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1770.2012.00492.x.

- Ferguson, Rob (2003). The Devil and the Disappearing Sea. Vancouver: Raincoast Books. ISBN 1-55192-599-0.

- Ryszard Kapuscinski, Imperium, Granta, 2019, ISBN 9781783785254

- Kasperson, Jeanne; Kasperson, Roger; Turner, B.L (1995). The Aral Sea Basin: A Man-Made Environmental Catastrophe. Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 92. ISBN 92-808-0848-6.

- Bendhun, François; Renard, Philippe (2004). "Indirect estimation of groundwater inflows into the Aral sea via a coupled water and salt mass balance model". Journal of Marine Systems. 47 (1–4): 35–50. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.12.007. Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Micklin, Philip (2007). "The Aral Sea Disaster". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 35 (4): 47–72. Bibcode:2007AREPS..35...47M. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.35.031306.140120.

- Sirjacobs, Damien; Grégoire, Marilaure; Delhez, Eric; Nihoul, JCJ (2004). "Influence of the Aral Sea negative water balance on its seasonal circulation patterns: use of a 3D hydrodynamic model". Journal of Marine Systems. 47 (1–4): 51–66. Bibcode:2004JMS....47...51S. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.12.008. hdl:2268/2793.

- Sun, Fangdi; Ma, Ronghua (14 June 2019). "Hydrologic changes of Aral Sea: A reveal by the combination of radar altimeter data and optical images". Annals of GIS. 25 (3): 247–261. doi:10.1080/19475683.2019.1626909.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aral Sea. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aral Sea. |

- Rivers Network : Aral Sea watersheds - webmap

- Post-Soviet Legacy: Aral Sea Pollution from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Aral Sea Foundation

- Union for Defence of the Aral Sea and Amudarya River

- "Syr Darya Control & Northern Aral Sea Phase I Project". World Bank Group - Kazakhstan. December 2006.

- Aral Sea from Space (time lapse)

- Swedish Aral Sea Society

- Google Earth view of the Aral Sea

- Youtube video: stranded ships on the dry bed of the Aral Sea being broken up for scrap