Fiji

Fiji (/ˈfiːdʒi/ (![]()

Republic of Fiji

| |

|---|---|

_(Polynesia_centered).svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Suva[2] 18°10′S 178°27′E |

| Official languages | Fijian English Fiji Hindi[3] |

| Recognised regional languages | Rotuman |

| Ethnic groups (2016[4]) |

|

| Religion (2007[5]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Fijian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary representative democratic republic |

| Jioji Konrote | |

| Frank Bainimarama | |

• Speaker of Parliament | Epeli Nailatikau |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence | |

• from the United Kingdom | 10 October 1970 |

• Republic | 7 October 1987 |

| Area | |

• Total | 18,274 km2 (7,056 sq mi) (151st) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 926,276[6] (161st) |

• 2017 census | 884,887[7] |

• Density | 46.4/km2 (120.2/sq mi) (148th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $9.112 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $10,251[8] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $5.223 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $5,876[8] |

| Gini (2013) | 36.4[9] medium |

| HDI (2019) | high · 98th |

| Currency | Fijian dollar (FJD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (FJT) |

| UTC+13[11] (FJST[12]) | |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +679 |

| ISO 3166 code | FJ |

| Internet TLD | .fj |

The majority of Fiji's islands formed through volcanic activity starting around 150 million years ago. Some geothermal activity still occurs today, on the islands of Vanua Levu and Taveuni.[16] The geothermal systems on Viti Levu are non-volcanic in origin, with low-temperature (c. 35–60 degrees Celsius) surface discharges. Sabeto Hot Springs near Nadi is a good example.[17] Humans have lived in Fiji since the second millennium BC—first Austronesians and later Melanesians, with some Polynesian influences. Europeans visited Fiji from the 17th century onwards,[18] and, after a brief period as an independent kingdom, the British established the Colony of Fiji in 1874. Fiji operated as a Crown colony until 1970, when it gained independence as the Dominion of Fiji. A military government declared a Republic in 1987 following a series of coups d'état. In a coup in 2006, Commodore Frank Bainimarama seized power. When the High Court ruled the military leadership unlawful in 2009, President Ratu Josefa Iloilo, whom the military had retained as the nominal Head of State, formally abrogated the 1997 Constitution and re-appointed Bainimarama as interim Prime Minister. Later in 2009, Ratu Epeli Nailatikau succeeded Iloilo as President.[19] After years of delays, a democratic election took place on 17 September 2014. Bainimarama's FijiFirst party won 59.2% of the vote, and international observers deemed the election credible.[20]

Fiji has one of the most developed economies in the Pacific[21] due to abundant forest, mineral, and fish resources. The currency is the Fijian dollar with the main sources of foreign exchange being the tourist industry, remittances from Fijians working abroad, and bottled water exports.[4] The Ministry of Local Government and Urban Development supervises Fiji's local government, which takes the form of city and town councils.[22]

Etymology

Fiji's main island is known as Viti Levu and it is from this that the name "Fiji" is derived, though the common English pronunciation is based on that of their island neighbours in Tonga. Its emergence can be described as follows:

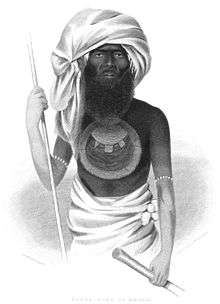

Fijians first impressed themselves on European consciousness through the writings of the members of the expeditions of Cook who met them in Tonga. They were described as formidable warriors and ferocious cannibals, builders of the finest vessels in the Pacific, but not great sailors. They inspired awe amongst the Tongans, and all their Manufactures, especially bark cloth and clubs, were highly valued and much in demand. They called their home Viti, but the Tongans called it Fisi, and it was by this foreign pronunciation, Fiji, first promulgated by Captain James Cook, that these islands are now known.[23]

"Feejee", the Anglicised spelling of the Tongan pronunciation,[24] was used in accounts and other writings until the late 19th century, by missionaries and other travellers visiting Fiji.[25][26]

History

Early settlement and development of Fijian culture

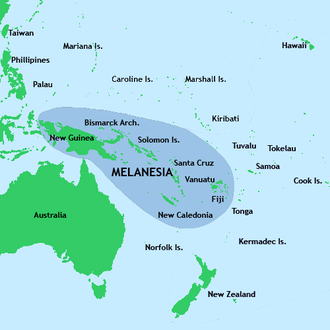

Located in the central Pacific Ocean, Fiji's geography has made it both a destination and a crossroads for migrations for many centuries.

.png)

Pottery art from Fijian towns shows that Fiji was settled by Austronesian peoples before or around 3500 to 1000 BC, with Melanesians following around a thousand years later, although the question of Pacific migration still lingers. It is believed that the Lapita people or the ancestors of the Polynesians settled the islands first but not much is known of what became of them after the Melanesians arrived; they may have had some influence on the new culture, and archaeological evidence shows that they would have then moved on to Samoa, Tonga and even Hawai'i. Archeological evidence shows signs of settlement on Moturiki Island from 600 BC and possibly as far back as 900 BC. Aspects of Fijian culture are similar to the Melanesian culture of the western Pacific but have a stronger connection to the older Polynesian cultures. Trade between Fiji and neighbouring archipelagos long before European contact is testified by the canoes made from native Fijian trees found in Tonga and Tongan words being part of the language of the Lau group of islands. Pots made in Fiji have been found in Samoa and even the Marquesas Islands.

In the 10th century, the Tu'i Tonga Empire was established in Tonga, and Fiji came within its sphere of influence. The Tongan influence brought Polynesian customs and language into Fiji. The empire began to decline in the 13th century.

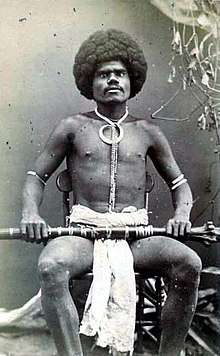

.jpg)

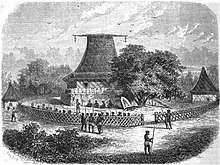

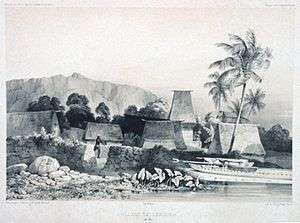

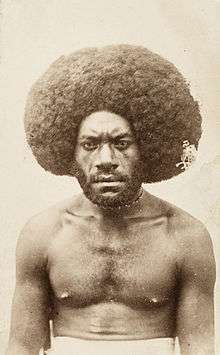

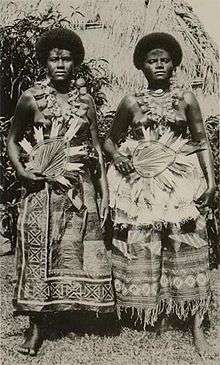

Across 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from east to west, Fiji has been a nation of many languages. Fiji's history was one of settlement but also of mobility and over the centuries, a unique Fijian culture developed. Large elegant watercraft with rigged sails called drua were constructed in Fiji, some being exported to Tonga. Distinctive village architecture evolved consisting of communal and individual bure and vale housing with an advanced system of ramparts and moats usually being constructed around the more important settlements. Pigs were domesticated for food and a variety of agricultural plantations such as bananas existed from an early stage. Villages would also be supplied with water brought in by constructed wooden aqueducts. Fijians lived in societies that were led by chiefs, elders and notable warriors. Spiritual leaders, often called bete, were also important cultural figures and the production and consumption of yaqona was part of their ceremonial and community rites. Fijians developed a monetary system where the polished teeth of the sperm whale, called tambua, became an active currency. A type of writing also existed which can be seen today in various petroglyphs around the islands.[27] They also produced a refined masi cloth textile industry with the material being used to make sails and clothes such as the malo and the liku. As with most other human civilisations, warfare was an important part of everyday life in pre-colonial Fiji. The Fijians were noted for their use of weapons especially war-clubs.[28][29] Fijians use many different types of clubs that can be broadly divided into two groups. The two main types of clubs they used were two handed clubs and small specialised throwing clubs called Ula.[30]

With the arrival of Europeans and colonialism in the late 1700s, many elements of Fijian culture were either repressed or modified to ensure European, namely British, control. This was especially the case concerning traditional Fijian spiritual beliefs. Early colonists and missionaries utilised and conflated the concept of cannibalism in Fiji to give a moral imperative for colonial intrusion.[31] By labelling native Fijian customs as "debased and primitive", they were able to promote a narrative that Fiji was a "paradise wasted on savage cannibals".[32] Extravagant stories made during the 19th century, such as that regarding Ratu Udre Udre who is said to have consumed 872 people and to have made a pile of stones to record his achievement,[33] permitted an enduring racial typecast of the "uncivilised" Fijian. Cannibalism, as an impression, was an effective racial tool deployed by the colonists that has endured through the 1900s and into the modern day. Authors such as Deryck Scarr,[34] for example, have perpetuated 19th century claims of "freshly killed corpses piled up for eating" and ceremonial mass human sacrifice on the construction of new houses and boats.[35] Although Fiji was known as the Cannibal Isles,[36] other more recent research doubts even the existence of cannibalism in Fiji.[37] This view is not without criticism, and perhaps the most accurate account of cannibalism in 19th century Fiji may come from William MacGregor, the long term chief medical officer in British colonial Fiji. During the Little War of 1876, he stated that the rare occasion of tasting of the flesh of the enemy was done "to indicate supreme hatred and not out of relish for a gastronomic treat".[38]

Recent archaeological research conducted on Fijian sites has begun to shed light on the accuracy of some of these European accounts of cannibalism. Studies conducted by scholars including Degusta,[39] Cochrane,[40] and Jones[41] provide evidence that cannibalism has been practised in Fiji through skeletal evidence of burning or cutting. In the Jones 2015 study, isotopic analysis of bone collagen provided evidence that human flesh had been consumed by Fijians, although it was likely a small and not necessarily regular part of the diet.[41] However, these archaeological accounts indicate that cannibalistic practices were likely more varied and less ubiquitous than European settlers originally described. Exocannibalism, or cannibalism of members of outsider tribes, and cannibalism practised as a means of violence or revenge probably play a significantly smaller role than European accounts suggested, with nonviolent and ritualistic practices being more likely.[40][41]

Early interaction with Europeans

Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first known European visitor to Fiji, sighting the northern island of Vanua Levu and the North Taveuni archipelago in 1643 while looking for the Great Southern Continent.[42]

James Cook, the British navigator, visited one of the southern Lau islands in 1774. It was not until 1789, however, that the islands were charted and plotted, when William Bligh, the castaway captain of HMS Bounty, passed Ovalau and sailed between the main islands of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu en route to Batavia, in what is now Indonesia. Bligh Water, the strait between the two main islands, is named after him, and for a time, the Fiji Islands were known as the Bligh Islands.

The first Europeans to maintain substantial contact with the Fijians were sandalwood merchants, whalers and "beche-de-mer" (sea cucumber) traders. The first whaling vessel known to have visited was the Ann and Hope in 1799 and she was followed by many others in the 19th century.[43] These ships came for drinking water, food and firewood and, later, for men to help man their ships. Some of the Europeans who came to Fiji in this period were accepted by the locals and were allowed to stay as residents. Probably the most famous of these was a Swede by the name of Kalle Svenson, better known as Charlie Savage. Savage was permitted to take wives and establish himself in a high rank in Bau society in exchange for helping defeat local adversaries. In 1813, however, Savage became a victim of this lifestyle and was killed in a botched raid.[44]

By the 1820s, Levuka was established as the first European-style town in Fiji, on the island of Ovalau. The market for "beche-de-mer" in China was lucrative and British and American merchants set up processing stations on various islands. Local Fijians were utilised to collect, prepare and pack the product which would then be shipped to Asia. A good cargo would result in a half-yearly profit of around $25,000 for the dealer.[45] The Fijian workers were often given firearms and ammunition as an exchange for their labour, and by the end of the 1820s most of the Fijian chiefs had muskets and many were skilled at using them. Some Fijian chiefs soon felt confident enough with their new weapons to forcibly obtain more destructive weaponry from the Europeans. In 1834, men from Viwa and Bau were able to take control of the French ship L'amiable Josephine and use its cannon against their enemies on the Rewa River, although they later ran it aground.[46]

Christian missionaries like David Cargill also arrived in the 1830s from recently converted regions such as Tonga and Tahiti, and by 1840 the European settlement at Levuka had grown to about 40 houses with former whaler, David Whippey, being a notable resident. The religious conversion of the Fijians was a gradual process which was observed first-hand by Captain Charles Wilkes of the United States Exploring Expedition. Wilkes wrote that "all the chiefs seemed to look upon Christianity as a change in which they had much to lose and little to gain".[47] Christianised Fijians, in addition to forsaking their spiritual beliefs, were pressured into cutting their hair short, adopting the sulu form of dress from Tonga and fundamentally changing their marriage and funeral traditions. This process of enforced cultural change was called lotu.[48] Intensification of conflict between the cultures increased and Wilkes was also involved in organising a large punitive expedition against the people of Malolo. He ordered an attack with rockets which acted as makeshift incendiary devices. The village, with the occupants trapped inside, quickly became an inferno with Wilkes himself noting that the "shouts of men were intermingled with the cries and shrieks of the women and children" as they burnt to death. Wilkes demanded the survivors should "sue for mercy" and if not "they must expect to be exterminated". Around 57 to 87 Maloloan people were killed in this encounter.[49]

Cakobau and the wars against Christian infiltration

The 1840s was a time of conflict where various Fiji clans attempted to assert dominance over each other. Eventually, a warlord by the name of Seru Epenisa Cakobau of Bau Island was able to become a powerful influence in the region. His father was Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa, the Vunivalu (a chiefly title meaning Warlord, often translated also as Paramount Chief) who had previously subdued much of western Fiji. Cakobau, following on from his father, became so dominant that he was able to expel the Europeans from Levuka for five years over a dispute about their giving of weapons to his local enemies. In the early 1850s, Cakobau went one step further and decided to declare war on all Christians. His plans were thwarted after the missionaries in Fiji received support from the already converted Tongans and the presence of a British warship. The Tongan Prince Enele Ma'afu, a Christian, had established himself on the Island of Lakeba in the Lau archipelago in 1848, forcibly converting the local people to the Methodist Church. Cakobau and other chiefs in the west of Fiji regarded Ma'afu as a threat to their power and resisted his attempts to expand Tonga's dominion. Cakobau's influence, however, began to wane and his heavy imposition of taxes on other Fijian chiefs, who saw him at best as first among equals, caused them to defect from him.[50]

Around this time the United States also became interested in asserting their power in the region and they threatened intervention following a number of incidents involving their consul in the Fiji islands, John Brown Williams. In 1849, Williams had his trading store looted following an accidental fire, caused by stray cannon fire during a Fourth of July celebration, and in 1853 the European settlement of Levuka was burnt to the ground. Williams blamed Cakobau for both these incidents and the US representative wanted Cakobau's capital at Bau destroyed in retaliation. A naval blockade was instead set up around the island which put further pressure on Cakobau to give up on his warfare against the foreigners and their Christian allies. Finally, on 30 April 1854, Cakobau offered his soro (supplication) and yielded to these forces. He underwent the "lotu" and converted to Christianity. The traditional Fijian temples in Bau were destroyed and the sacred nokonoko trees were cut down. Cakobau and his remaining men were then compelled to join with the Tongans, backed by the Americans and British, to subjugate the remaining chiefs in the region who still refused to convert. These chiefs were soon defeated with Qaraniqio of the Rewa being poisoned and Ratu Mara of Kaba being hanged in 1855. After these wars, most regions of Fiji, except for the interior highland areas, had been forced into giving up much of their traditional systems and were now vassals of Western interest. Cakobau was retained as a largely symbolic representative of a few Fijian peoples and was allowed to take the ironic and self proclaimed title of "Tui Viti" ("King of Fiji"), but the overarching control now lay with foreign powers.[51]

Cotton, confederacies and the Kai Colo

The rising price of cotton in the wake of the American Civil War (1861–1865) caused an influx of hundreds of settlers to Fiji in the 1860s from Australia and the United States in order to obtain land and grow cotton. Since there was still a lack of functioning government in Fiji, these planters were often able to get the land in violent or fraudulent ways such as exchanging weapons or alcohol with Fijians who may or may not have been the true owners. Although this made for cheap land acquisition, competing land claims between the planters became problematic with no unified government to resolve the disputes. In 1865, the settlers proposed a confederacy of the seven main native kingdoms in Fiji to establish some sort of government. This was initially successful and Cakobau was elected as the first president of the confederacy.[52]

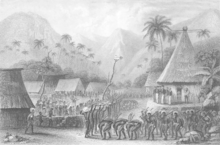

With the demand for land high, the white planters started to push into the hilly interior of Viti Levu, the largest island in the archipelago. This put them into direct confrontation with the Kai Colo, which was a general term to describe the various Fijian clans resident to these inland districts. The Kai Colo were still living a mostly traditional lifestyle, they were not Christianised and they were not under the rule of Cakobau or the confederacy. In 1867, a travelling missionary named Thomas Baker was killed by Kai Colo in the mountains at the headwaters of the Sigatoka River. The acting British consul, John Bates Thurston, demanded that Cakobau lead a force of Fijians from coastal areas to suppress the Kai Colo. Cakobau eventually led a campaign into the mountains but suffered a humiliating loss with 61 of his fighters being killed.[53] Settlers also came into conflict with the local eastern Kai Colo people called the Wainimala. John Bates Thurston called in the Australia Station section of the Royal Navy for assistance. The Navy duly sent Commander Rowley Lambert and HMS Challenger to conduct a punitive mission against the Wainimala. An armed force of 87 men shelled and burnt the village of Deoka and a skirmish ensued which resulted in the deaths of over forty Wainimala.[54]

Kingdom of Fiji (1871–1874)

.svg.png)

After the collapse of the confederacy, Ma'afu established a stable administration in the Lau Islands and the Tongans, therefore, were again becoming influential. Other foreign powers such as the United States were also considering the possibility of annexing Fiji. This situation was not appealing to many settlers, almost all of whom were British subjects from Australia. Britain, however, still refused to annex the country and subsequently a compromise was needed.[55]

In June 1871, George Austin Woods, an ex-lieutenant of the Royal Navy, managed to influence Cakobau and organise a group of like-minded settlers and chiefs into forming a governing administration. Cakobau was declared the monarch (Tui Viti) and the Kingdom of Fiji was established. Most Fijian chiefs agreed to participate and even Ma'afu chose to recognise Cakobau and participate in the constitutional monarchy. However, many of the settlers had come from British colonies like Victoria and New South Wales where negotiation with the Indigenous people almost universally involved the barrel of a gun. As a result, several aggressive, racially motivated opposition groups, such as the British Subjects Mutual Protection Society, sprouted up. One group called themselves the Ku Klux Klan in a homage to the white supremacist group in America.[56] However, when respected individuals such as Charles St Julian, Robert Sherson Swanston and John Bates Thurston were appointed by Cakobau, a degree of authority was established.[57]

With the rapid increase in white settlers into the country, the desire for land acquisition also intensified. Once again, conflict with the Kai Colo in the interior of Viti Levu ensued. In 1871, the killing of two settlers named Spiers and Mackintosh near the Ba River (Fiji) in the north-west of the island prompted a large punitive expedition of white farmers, imported slave labourers and coastal Fijians to be organised. This group of around 400 armed vigilantes, including veterans of the US Civil War, had a battle with the Kai Colo near the village of Cubu in which both sides had to withdraw. The village was destroyed and the Kai Colo, despite being armed with muskets, received numerous casualties.[58] The Kai Colo responded by making frequent raids on the settlements of the whites and Christian Fijians throughout the district of Ba.[59] Likewise, in the east of the island on the upper reaches of the Rewa River, villages were burnt and a "great many" Kai Colo were shot by the vigilante settler squad called the Rewa Rifles.[60]

Although the Cakobau government did not approve of the settlers taking justice into their own hands, it did want the Kai Colo subjugated and their land sold off. The solution was to form an army. Robert S. Swanston, the minister for Native Affairs in the Kingdom, organised the training and arming of suitable Fijian volunteers and prisoners to become soldiers in what was invariably called the King's Troops or the Native Regiment. In a similar system to the Native Police that was present in the colonies of Australia, two white settlers, James Harding and W. Fitzgerald, were appointed as the head officers of this paramilitary brigade.[61] The formation of this force did not sit well with many of the white plantation owners as they did not trust an army of Fijians to protect their interests.

The situation intensified further in early 1873 when the Burns family were killed by a Kai Colo raid in the Ba River area. The Cakobau government deployed 50 King's Troopers to the region under the command of Major Fitzgerald to restore order. The local whites, with their own large force under the leadership of Mr White and Mr de Courcy Ireland, refused their posting and a further deployment of another 50 troops under Captain Harding was sent to emphasise the government's authority. To prove the worth of the Native Regiment, this augmented force went into the interior and massacred about 170 Kai Colo people at Na Korowaiwai. Upon returning to the coast, the force were met by the white settlers who still saw the government troops as a threat. A skirmish between the government's troops and the white settlers' brigade was only prevented by the timely intervention of Captain William Cox Chapman of HMS Dido who promptly detained Mr White and Mr de Courcy Ireland, forcing the group to disband. The authority of the King's Troops and the Cakobau government to crush the Kai Colo was now total.[62]

From March to October 1873, a force of about 200 King's Troops under the general administration of R.S. Swanston with around 1000 coastal Fijian and white volunteer auxiliaries, led a campaign throughout the highlands of Viti Levu to annihilate the Kai Colo. Major Fitzgerald and Major H.C. Thurston (the brother of John Bates Thurston) led a two pronged attack throughout the region. The combined forces of the different clans of the Kai Colo made a stand at the village of Na Culi. The Kai Colo were defeated with dynamite and fire being used to flush them out from their defensive positions amongst the mountain caves. Many Kai Colo were killed and one of the main leaders of the hill clans, Ratu Dradra, was forced to surrender with around 2000 men, women and children being taken prisoner and sent to the coast.[63] In the months after this defeat, the only main resistance was from the clans around the village of Nibutautau. Major H.C. Thurston crushed this resistance in the two months following the battle at Na Culi. Villages were burnt, Kai Colo were killed and a further large number of prisoners were taken.[64] The operations were now over. About 1000 of the prisoners (men, women and children) were sent to Levuka where some were hanged, the rest being sold into slavery and forced to work on various plantations throughout the islands.[65]

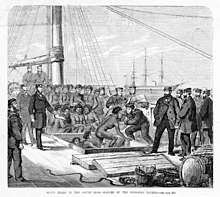

Blackbirding and slavery in Fiji

The blackbirding era began in Fiji in 1865 when the first New Hebridean and Solomon Island labourers were transported there to work on cotton plantations. The American Civil War had cut off the supply of cotton to the international market when the Union blockaded Confederate ports. Cotton cultivation was potentially an extremely profitable business. Thousands of European planters flocked to Fiji to establish plantations but found the natives unwilling to adapt to their plans. They sought labour from the Melanesian islands. On 5 July 1865 Ben Pease received the first licence to provide 40 labourers from the New Hebrides to Fiji.[66]

The British and Queensland governments tried to regulate this recruiting and transport of labour. Melanesian labourers were to be recruited for a term of three years, paid three pounds per year, issued with basic clothing and given access to the company store for supplies. Most Melanesians were recruited by deceit, usually being enticed aboard ships with gifts, and then locked up. The living and working conditions for them in Fiji were worse than those suffered by the later Indian indentured labourers. In 1875, the chief medical officer in Fiji, Sir William MacGregor, listed a mortality rate of 540 out of every 1000 labourers. After the expiry of the three-year contract, the government required captains to transport the labourers back to their villages, but most ship captains dropped them off at the first island they sighted off the Fiji waters. The British sent warships to enforce the law (Pacific Islanders' Protection Act of 1872) but only a small proportion of the culprits were prosecuted.

A notorious incident of the blackbirding trade was the 1871 voyage of the brig Carl, organised by Dr James Patrick Murray,[67] to recruit labourers to work in the plantations of Fiji. Murray had his men reverse their collars and carry black books, so to appear to be church missionaries. When islanders were enticed to a religious service, Murray and his men would produce guns and force the islanders onto boats. During the voyage Murray shot about 60 islanders. He was never brought to trial for his actions, as he was given immunity in return for giving evidence against his crew members.[68][67] The captain of the Carl, Joseph Armstrong, was later sentenced to death.[67][69]

In addition to the blackbirded labour from other Pacific islands, thousands of people indigenous to the Fijian archipelago were also sold into slavery on the plantations. As the white settler backed Cakobau government, and later the British colonial government, subjugated areas in Fiji under its power, the resultant prisoners of war were regularly sold at auction to the planters. This not only provided a source of revenue for the government, but also dispersed the rebels to different, often isolated islands where the plantations were located. The land that was occupied by these people before they became slaves was then also sold off for additional revenue. An example of this is the Lovoni people of Ovalau island, who after being defeated in a war with the Cakobau government in 1871, were rounded up and sold off to the settlers at £6 per head. Two thousand Lovoni men, women and children were sold and their period of slavery lasted five years.[70] Likewise, after the Kai Colo wars in 1873, thousands of people from the hill tribes of Viti Levu were sent to Levuka and sold into slavery.[71] Warnings from the Royal Navy stationed in the area that buying these people was illegal were largely given without enforcement and the British consul in Fiji, Edward Bernard Marsh, regularly turned a blind eye to this type of labour trade.[72]

Colonisation

Despite achieving military victories over the Kai Colo, the Cakobau government was faced with problems of legitimacy and economic viability. Indigenous Fijians and white settlers refused to pay taxes and the cotton price had collapsed. With these major issues in mind, John Bates Thurston approached the British government, at Cakobau's request, with another offer to cede the islands. The newly elected Tory British government under Benjamin Disraeli encouraged expansion of the empire and was therefore much more sympathetic to annexing Fiji than it had been previously. The murder of Bishop John Coleridge Patteson of the Melanesian Mission at Nukapu in the Reef Islands had provoked public outrage, which was compounded by the massacre by crew members of more than 150 Fijians on board the brig Carl. Two British commissioners were sent to Fiji to investigate the possibility of an annexation. The question was complicated by manoeuvrings for power between Cakobau and his old rival, Ma'afu, with both men vacillating for many months. On 21 March 1874, Cakobau made a final offer, which the British accepted. On 23 September, Sir Hercules Robinson, soon to be appointed the British Governor of Fiji, arrived on HMS Dido and received Cakobau with a royal 21-gun salute. After some vacillation, Cakobau agreed to renounce his Tui Viti title, retaining the title of Vunivalu, or Protector. The formal cession took place on 10 October 1874, when Cakobau, Ma'afu, and some of the senior Chiefs of Fiji signed two copies of the Deed of Cession. Thus the Colony of Fiji was founded; 96 years of British rule followed.

Measles epidemic of 1875

To celebrate the annexation of Fiji, Hercules Robinson, who was Governor of New South Wales at the time, took Cakobau and his two sons to Sydney. There was a measles outbreak in that city[73] and the three Fijians all came down with the disease. On returning to Fiji, the colonial administrators decided not to quarantine the ship that the convalescents travelled in. This was despite the British having a very extensive knowledge of the devastating effect of infectious disease on an unexposed population. In 1875–76 the resulting epidemic of measles killed over 40,000 Fijians,[74] about one-third of the Fijian population.[75] Some Fijians who survived were of the opinion that this failure of quarantine was a deliberate action to introduce the disease into the country. Whether this is the case or not, the decision, which was one of the first acts of British control in Fiji, was at the very least grossly negligent.[76]

Sir Arthur Gordon and the "Little War"

Sir Hercules Robinson was replaced as Governor of Fiji in June 1875 by Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon. Gordon was immediately faced with an insurgency of the Qalimari and Kai Colo people. In early 1875, colonial administrator Edgar Leopold Layard, had met with thousands of highland clans at Navuso in Viti Levu to formalise their subjugation to British rule and the Christian religion. Layard and his delegation managed to spread the measles epidemic to the highlanders, causing mass deaths in this population. As a result, anger at the British colonists flared throughout the region and a widespread uprising quickly took hold. Villages along the Sigatoka River and in the highlands above this area refused British control and Gordon was tasked with quashing this rebellion.[77]

In what Gordon himself termed the "Little War", the suppression of this uprising took the form of two co-ordinated military campaigns in the western half of Viti Levu. The first was conducted by Gordon's second cousin, Arthur John Lewis Gordon, against the Qalimari insurgents along the Sigatoka River. The second campaign was led by Louis Knollys against the Kai Colo in the mountains to the north of the river. Governor Gordon invoked a type of martial law in the area where A.J.L. Gordon and Knollys had absolute power to conduct their missions outside of any restrictions of legislation. The two groups of rebels were kept isolated from each other by a force led by Walter Carew and George Le Hunte who were stationed at Nasaucoko. Carew also ensured the rebellion did not spread east by securing the loyalty of the Wainimala people of the eastern highlands. The war involved the use of the soldiers of the old Native Regiment of Cakobau supported by around 1500 Christian Fijian volunteers from other areas of Viti Levu. The colonial New Zealand Government provided most of the advanced weapons for the army including one hundred Snider rifles.

The campaign along the Sigatoka River was conducted under a scorched earth policy whereby numerous rebel villages were burnt and their fields ransacked. After the capture and destruction of the main fortified towns of Koroivatuma, Bukutia and Matanavatu, the Qalimari surrendered en masse. Those who weren't killed in the fighting were taken prisoner and sent to the coastal town of Cuvu. This included 827 men, women and children as well as the leader of the insurgents, a man named Mudu. The women and children were distributed to places like Nadi and Nadroga. Of the men, 15 were sentenced to death at a hastily conducted trial at Sigatoka. Governor Gordon was present, but chose to leave the judicial responsibility to his relative, A.J.L. Gordon. Four were hanged and ten, including Mudu, were shot with one prisoner managing to escape. By the end of proceedings the Governor noted that "my feet were literally stained with the blood that I had shed".[78]

The northern campaign against the Kai Colo in the highlands was similar but involved removing the rebels from large, well protected caves in the region. Knollys managed to clear the caves "after some considerable time and large expenditure of ammunition". The occupants of these caves included whole communities and as a result many men, women and children were either killed or wounded in these operations. The rest were taken prisoner and sent to the towns on the northern coast. The chief medical officer in British Fiji, William MacGregor, also took part both in killing Kai Colo and tending to their wounded. After the caves were taken, the Kai Colo surrendered and their leader, Bisiki, was captured. Various trials were held, mostly at Nasaucoko under Le Hunte, and 32 men were either hanged or shot including Bisiki, who was killed trying to escape.[79]

By the end of October 1876, the "Little War" was over and Gordon had succeeded in vanquishing the rebels in the interior of Viti Levu. Those insurgents who weren't killed or executed were sent into exile with hard labour for up to 10 years. Some non-combatants were allowed to return to rebuild their villages, but many areas in the highlands were ordered by Gordon to remain depopulated and in ruins. Gordon also constructed a military fortress, Fort Canarvon, at the headwaters of the Sigatoka River where a large contingent of soldiers were based to maintain British control. He renamed the Native Regiment, the Armed Native Constabulary to lessen its appearance of being a military force.[79]

To further consolidate social control throughout the colony, Governor Gordon introduced a system of appointed chiefs and village constables in the various districts to both enact his orders and report any disobedience from the populace. Gordon adopted the chiefly titles Roko and Buli to describe these deputies and established a Great Council of Chiefs which was directly subject to his authority as Supreme Chief. This body remained in existence until being suspended by the Military-backed interim government in 2007 and only abolished in 2012. Gordon also extinguished the ability of Fijians to own, buy or sell land as individuals, the control being transferred to colonial authorities.[80]

Indian indenture system in Fiji

Gordon decided in 1878 to import indentured labourers from India to work on the sugarcane fields that had taken the place of the cotton plantations. The 463 Indians arrived on 14 May 1879 – the first of some 61,000 that were to come before the scheme ended in 1916. The plan involved bringing the Indian workers to Fiji on a five-year contract, after which they could return to India at their own expense; if they chose to renew their contract for a second five-year term, they would be given the option of returning to India at the government's expense, or remaining in Fiji. The great majority chose to stay. The Queensland Act, which regulated indentured labour in Queensland, was made law in Fiji also.

Between 1879 and 1916, tens of thousands of Indians moved to Fiji to work as indentured labourers, especially on sugarcane plantations. A total of 42 ships made 87 voyages, carrying Indian indentured labourers to Fiji. Initially the ships brought labourers from Calcutta, but from 1903 all ships except two also brought labourers from Madras and Bombay. A total of 60,965 passengers left India but only 60,553 (including births at sea) arrived in Fiji. A total of 45,439 boarded ships in Calcutta and 15,114 in Madras. Sailing ships took, on average, seventy-three days for the trip while steamers took 30 days. The shipping companies associated with the labour trade were Nourse Line and British-India Steam Navigation Company.

Repatriation of indentured Indians from Fiji began on 3 May 1892, when the British Peer brought 464 repatriated Indians to Calcutta. Various ships made similar journeys to Calcutta and Madras, concluding with Sirsa's 1951 voyage. In 1955 and 1956, three ships brought Indian labourers from Fiji to Sydney, from where the labourers flew to Bombay. Indentured Indians wishing to return to India were given two options. One was travel at their own expense and the other free of charge but subject to certain conditions. To obtain free passage back to India, labourers had to have been above age twelve upon arrival, completed at least five years of service and lived in Fiji for a total of ten consecutive years. A child born to these labourers in Fiji could accompany his or her parents or guardian back to India if he or she was under twelve. Due to the high cost of returning at their own expense, most indentured immigrants returning to India left Fiji around ten to twelve years after their arrival. Indeed, just over twelve years passed between the voyage of the first ship carrying indentured Indians to Fiji (the Leonidas, in 1879) and the first ship to take Indians back (the British Peer, in 1892). Given the steady influx of ships carrying indentured Indians to Fiji up until 1916, repatriated Indians generally boarded these same ships on their return voyage. The total number of repatriates under the Fiji indenture system is recorded as 39,261, while the number of arrivals is said to have been 60,553. Because the return figure includes children born in Fiji, many of the indentured Indians never returned to India. Direct return voyages by ship ceased after 1951. Instead, arrangements were made for flights from Sydney to Bombay, the first of which departed in July 1955. Labourers still travelled to Sydney by ship.

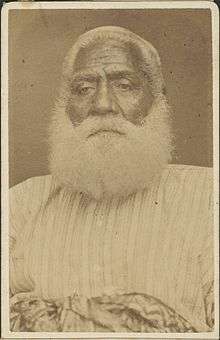

The Tuka rebellions

With almost all aspects of indigenous Fijian social life being controlled by British authorities, a number of charismatic individuals preaching dissent and return to pre-colonial culture were able to forge a following amongst the disenfranchised. These movements were called Tuka, which roughly translates as "those who stand up". The first Tuka movement, was led by Ndoongumoy, better known as Navosavakandua which means "he who speaks only once". He told his followers that if they returned to traditional ways and worshipped traditional deities such as Degei and Rokola, their current condition would be transformed with the whites and their puppet Fijian chiefs being subservient to them. Navosavakandua was previously exiled from the Viti Levu highlands in 1878 for disturbing the peace and the British quickly arrested him and his followers after this open display of rebellion. He was again exiled, this time to Rotuma where he died soon after his 10-year sentence ended.[81]

Other Tuka organisations, however, soon appeared. The British were ruthless in their suppression of both the leaders and followers with figureheads such as Sailose being banished to an asylum for 12 years. In 1891, entire populations of villages who were sympathetic to the Tuka ideology were deported as punishment.[82] Three years later in the highlands of Vanua Levu, where locals had re-engaged in traditional religion, the Governor of Fiji, John Bates Thurston, ordered in the Armed Native Constabulary to destroy the towns and the religious relics. Leaders were jailed and villagers exiled or forced to amalgamate into government-run communities.[83] Later, in 1914, Apolosi Nawai came to the forefront of Fijian Tuka resistance by founding a co-operative company that would legally monopolise the agricultural sector and boycott European planters. The company was called the Viti Kabani and it was a hugely successful. The British and their proxy Council of Chiefs were not able to prevent the Viti Kabani's rise and again the colonists were forced to send in the Armed Native Constabulary. Apolosi and his followers were arrested in 1915 and the company collapsed in 1917. Over the next 30 years, Apolosi was re-arrested, jailed and exiled, with the British viewing him as a threat right up to his death in 1946.[84]

Fiji in World War I and II

Fiji was only peripherally involved in World War I. One memorable incident occurred in September 1917 when Count Felix von Luckner arrived at Wakaya Island, off the eastern coast of Viti Levu, after his raider, SMS Seeadler, had run aground in the Cook Islands following the shelling of Papeete in the French territory of Tahiti. On 21 September, the district police inspector took a number of Fijians to Wakaya, and von Luckner, not realising that they were unarmed, unwittingly surrendered.

Citing unwillingness to exploit the Fijian people, the colonial authorities did not permit Fijians to enlist. One Fijian of chiefly rank, a greatgrandson of Cakobau's, did join the French Foreign Legion, however, and received France's highest military decoration, the Croix de Guerre. After going on to complete a Law degree at Oxford University, this same chief returned to Fiji in 1921 as both a war hero and the country's first-ever university graduate. In the years that followed, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, as he was later known, established himself as the most powerful chief in Fiji and forged embryonic institutions for what would later become the modern Fijian nation.

.svg.png)

By the time of World War II, the United Kingdom had reversed its policy of not enlisting natives, and many thousands of Fijians volunteered for the Fiji Infantry Regiment, which was under the command of Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, another greatgrandson of Seru Epenisa Cakobau. The regiment was attached to New Zealand and Australian army units during the war.

Because of its central location, Fiji was selected as a training base for the Allies. An airstrip was built at Nadi (later to become an international airport), and gun emplacements studded the coast. Fijians gained a reputation for bravery in the Solomon Islands campaign, with one war correspondent describing their ambush tactics as "death with velvet gloves". Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu, of Yucata, was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, as a result of his bravery in the Battle of Bougainville.

Responsible government

A constitutional conference was held in London in July 1965, to discuss constitutional changes with a view to introducing responsible government. Indo-Fijians, led by A. D. Patel, demanded the immediate introduction of full self-government, with a fully elected legislature, to be elected by universal suffrage on a common voters' roll. These demands were vigorously rejected by the ethnic Fijian delegation, who still feared loss of control over natively owned land and resources should an Indo-Fijian dominated government come to power. The British made it clear, however, that they were determined to bring Fiji to self-government and eventual independence. Realizing that they had no choice, Fiji's chiefs decided to negotiate for the best deal they could get.

A series of compromises led to the establishment of a cabinet system of government in 1967, with Ratu Kamisese Mara as the first Chief Minister. Ongoing negotiations between Mara and Sidiq Koya, who had taken over the leadership of the mainly Indo-Fijian National Federation Party on Patel's death in 1969, led to a second constitutional conference in London, in April 1970, at which Fiji's Legislative Council agreed on a compromise electoral formula and a timetable for independence as a fully sovereign and independent nation within the Commonwealth. The Legislative Council would be replaced with a bicameral Parliament, with a Senate dominated by Fijian chiefs and a popularly elected House of Representatives. In the 52-member House, Native Fijians and Indo-Fijians would each be allocated 22 seats, of which 12 would represent Communal constituencies comprising voters registered on strictly ethnic roles, and another 10 representing National constituencies to which members were allocated by ethnicity but elected by universal suffrage. A further 8 seats were reserved for "General electors" – Europeans, Chinese, Banaban Islanders, and other minorities; 3 of these were "communal" and 5 "national". With this compromise, Fiji became independent on 10 October 1970.

Independence (1970)

The British granted Fiji independence in 1970. Democratic rule was interrupted by two military coups in 1987 precipitated by a growing perception that the government was dominated by the Indo-Fijian (Indian) community. The second 1987 coup saw both the Fijian monarchy and the Governor General replaced by a non-executive president and the name of the country changed from Dominion of Fiji to Republic of Fiji and then in 1997 to Republic of the Fiji Islands. The two coups and the accompanying civil unrest contributed to heavy Indo-Fijian emigration; the resulting population loss resulted in economic difficulties and ensured that Melanesians became the majority.[85]

In 1990, the new constitution institutionalised ethnic Fijian domination of the political system. The Group Against Racial Discrimination (GARD) was formed to oppose the unilaterally imposed constitution and to restore the 1970 constitution. In 1992 Sitiveni Rabuka, the Lieutenant Colonel who had carried out the 1987 coup, became Prime Minister following elections held under the new constitution. Three years later, Rabuka established the Constitutional Review Commission, which in 1997 wrote a new constitution which was supported by most leaders of the indigenous Fijian and Indo-Fijian communities. Fiji was re-admitted to the Commonwealth of Nations.

The year 2000 brought along another coup, instigated by George Speight, which effectively toppled the government of Mahendra Chaudhry, who in 1997 had become the country's first Indo-Fijian Prime Minister following the adoption of the new constitution. Commodore Frank Bainimarama assumed executive power after the resignation, possibly forced, of President Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara. Later in 2000, Fiji was rocked by two mutinies when rebel soldiers went on a rampage at Suva's Queen Elizabeth Barracks. The High Court ordered the reinstatement of the constitution, and in September 2001, to restore democracy, a general election was held which was won by interim Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase's Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua party.[86]

In 2005, the Qarase government amid much controversy proposed a Reconciliation and Unity Commission with power to recommend compensation for victims of the 2000 coup and amnesty for its perpetrators. However, the military, especially the nation's top military commander, Frank Bainimarama, strongly opposed this bill. Bainimarama agreed with detractors who said that to grant amnesty to supporters of the present government who had played a role in the violent coup was a sham. His attack on the legislation, which continued unremittingly throughout May and into June and July, further strained his already tense relationship with the government.

In late November and early December 2006, Bainimarama was instrumental in the 2006 Fijian coup d'état. Bainimarama handed down a list of demands to Qarase after a bill was put forward to parliament, part of which would have offered pardons to participants in the 2000 coup attempt. He gave Qarase an ultimatum date of 4 December to accede to these demands or to resign from his post. Qarase adamantly refused either to concede or resign, and on 5 December the president, Ratu Josefa Iloilo, was said to have signed a legal order dissolving the parliament after meeting with Bainimarama.

In April 2009, the Fiji Court of Appeal ruled that the 2006 coup had been illegal, sparking the 2009 Fijian constitutional crisis. President Iloilo abrogated the constitution, removed all office holders under the constitution including all judges and the governor of the Central Bank. He then reappointed Bainimarama under his "New Order" as interim Prime Minister and imposed a "Public Emergency Regulation" limiting internal travel and allowing press censorship.

Relative to its size, Fiji has fairly large armed forces, and has been a major contributor to UN peacekeeping missions in various parts of the world. In addition, a significant number of former military personnel have served in the lucrative security sector in Iraq following the 2003 US-led invasion.[87]

Geography

.jpg)

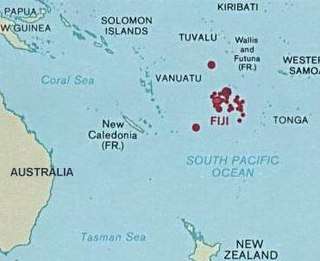

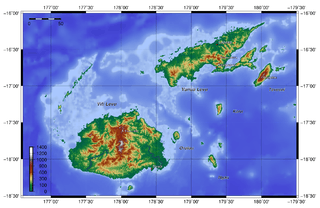

Fiji covers a total area of some 194,000 square kilometres (75,000 sq mi) of which around 10% is land.

Fiji is the hub of the South West Pacific, midway between Vanuatu and Tonga. The archipelago is located between 176° 53′ east and 178° 12′ west. The archipelago is roughly 498,000 square miles and less than 2 percent is dry land.The 180° meridian runs through Taveuni but the International Date Line is bent to give uniform time (UTC+12) to all of the Fiji group. With the exception of Rotuma, the Fiji group lies between 15° 42′ and 20° 02′ south. Rotuma is located 220 nautical miles (410 km; 250 mi) north of the group, 360 nautical miles (670 km; 410 mi) from Suva, 12° 30′ south of the equator. Fiji lies approximately 5,100 km southwest of Hawaii and roughly 3,150 km from Sydney, Australia.[88][89]

Fiji consists of 332[4] islands (of which 106 are inhabited) and 522 smaller islets. The two most important islands are Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, which account for about three-quarters of the total land area of the country. The islands are mountainous, with peaks up to 1,324 metres (4,341 ft), and covered with thick tropical forests.

The highest point is Mount Tomanivi on Viti Levu. Viti Levu hosts the capital city of Suva, and is home to nearly three-quarters of the population. Other important towns include Nadi (the location of the international airport),[14] and Lautoka, Fiji's second city with large sugar cane mills and a seaport.

The main towns on Vanua Levu are Labasa and Savusavu. Other islands and island groups include Taveuni and Kadavu (the third and fourth largest islands, respectively), the Mamanuca Group (just off Nadi) and Yasawa Group, which are popular tourist destinations, the Lomaiviti Group, off Suva, and the remote Lau Group. Rotuma, some 270 nautical miles (500 km; 310 mi) north of the archipelago, has a special administrative status in Fiji. Ceva-i-Ra, an uninhabited reef, is located about 250 nautical miles (460 km; 290 mi) southwest of the main archipelago.

Climate

The climate in Fiji is tropical marine and warm year round with minimal extremes. The warm season is from November to April and the cooler season lasts from May to October. Temperatures in the cool season still average 22 °C (72 °F). Rainfall is variable, with the warm season experiencing heavier rainfall, especially inland. For the larger islands, rainfall is heavier on the southeast portions of the islands than on the northwest portions, with consequences for agriculture in those areas. Winds are moderate, though cyclones occur about once a year (10–12 times per decade).[90][91][92]

On 20 February 2016, Fiji was hit by the full force of Cyclone Winston, the only Category 5 tropical cyclone to make landfall in the nation. Winston destroyed tens of thousands of homes across the island, killing 44 people and causing an estimated FJ$2 billion (US$1 billion) in damage.[93][94]

Politics

Politics in Fiji normally take place in the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic wherein the Prime Minister of Fiji is the head of government and the President the Head of State, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government, legislative power is vested in both the government and the Parliament of Fiji, and the judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Regional and international associations

Fiji is heavily engaged with or has membership in Pacific regional development organisations. It has been a leading member of the Pacific Community since 1971 and hosts the largest SPC presence of any Pacific nation.

Fiji is also home to many international organisation regional offices[95] including:

Global Environment Facility (GEF) United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) World Health Organization (WHO) International Labour Organization (ILO) United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women) Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) United Nations ESCAP Subregional Office for the Pacific (UN-ESCAP) UN Office for the Coordination of the Humanitarian Affairs in the Pacific (UNOCHA) UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Subregional Office for the Pacific (UNISDR) United Nations Department of Safety and Security (UNDSS) International Monetary Fund Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (IMF) United Nations Human Settlement Programme Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (UN-Habitat) United Nations Volunteers (UNV) United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD) International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

2006 military takeover

Citing corruption in the government, Commodore Frank Bainimarama, Commander of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces, staged a military takeover on 5 December 2006 against the prime minister that he had installed after a 2000 coup. There had also been a military coup in 1987. The commodore took over the powers of the presidency and dissolved the parliament, paving the way for the military to continue the takeover. The coup was the culmination of weeks of speculation following conflict between the elected prime minister, Laisenia Qarase, and Commodore Bainimarama. Bainimarama had repeatedly issued demands and deadlines to the prime minister. A particular issue was previously pending legislation to pardon those involved in the 2000 coup. Bainimarama named Jona Senilagakali as caretaker prime minister. The next week Bainimarama said he would ask the Great Council of Chiefs to restore executive powers to the president, Ratu Josefa Iloilo.[96]

On 4 January 2007, the military announced that it was restoring executive power to president Iloilo,[97] who made a broadcast endorsing the actions of the military.[98] The next day, Iloilo named Bainimarama as the interim prime minister,[99] indicating that the military was still effectively in control. In the wake of the takeover, reports emerged of alleged intimidation of some of those critical of the interim regime.

On 9 April 2009, the Court of Appeal overturned the High Court decision that Cdre. Bainimarama's takeover of Qarase's government was lawful and declared the interim government to be illegal. Bainimarama agreed to step down as interim PM immediately, along with his government, and president Iloilo was to appoint "a distinguished person independent of the parties to this litigation as caretaker Prime Minister, ...to direct the issuance of writs for an election".

On 10 April 2009, President Iloilo suspended the Constitution of Fiji, dismissed the Court of Appeal and, in his own words, "appoint[ed] [him]self as the Head of the State of Fiji under a new legal order".[100] As President, Iloilo had been Head of State prior to his abrogation of the Constitution, but that position had been determined by the Constitution itself. The "new legal order" did not depend on the Constitution, thus requiring a "reappointment" of the Head of State. "You will agree with me that this is the best way forward for our beloved Fiji", he said. Bainimarama was re-appointed as Interim Prime Minister; he, in turn, re-instated his previous cabinet.

On 2 May 2009, Fiji became the first nation ever to have been suspended from participation in the Pacific Islands Forum, for its failure to hold democratic elections by the date promised.[101][102] Nevertheless, it remains a member of the Forum.

On 1 September 2009, Fiji was suspended from the Commonwealth of Nations. The action was taken because Cdre. Bainimarama failed to hold elections by 2010 as the Commonwealth of Nations had demanded after the 2006 coup. Cdre. Bainimarama stated a need for more time to end a voting system that heavily favoured ethnic Fijians at the expense of the multi-ethnic minorities. Critics, however, claimed that he had suspended the constitution and was responsible for human rights violations by arresting and detaining opponents.[103][104]

In his 2010 New Year's address, Cdre. Bainimarama announced the lifting of the Public Emergency Regulations (PER). However, the PER was not rescinded until 8 January 2012 and the Suva Philosophy Club was the first organisation to reorganise and convene public meetings.[105] The PER had been put in place in April 2009 when the former constitution was abrogated. The PER had allowed restrictions on speech, public gatherings, and censorship of news media and had given security forces added powers. He also announced a nationwide consultation process leading to a new Constitution under which the 2014 elections were to be held.

On 14 March 2014, the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group voted to change Fiji's full suspension from the Commonwealth of Nations to a suspension from the councils of the Commonwealth, allowing them to participate in a number of Commonwealth activities, including the 2014 Commonwealth Games.[106][107] The suspension was lifted in September 2014.[108]

A general election took place on 17 September 2014. Bainimarama's FijiFirst party won with 59.2% of the vote, and the election was deemed credible by a group of international observers from Australia, India and Indonesia.[20]

Armed forces and law enforcement

The military consists of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) with a total manpower of 3,500 active soldiers and 6,000 reservists, and includes a Navy Unit of 300 personnel.

The Land Force comprises the Fiji Infantry Regiment (regular and territorial force organised into six light infantry battalions), Fiji Engineer Regiment, Logistic Support Unit and Force Training Group. The two regular battalions are traditionally stationed overseas on peacekeeping duties.

The Law Enforcement branch is composed of:

- Fiji Police Force[109]

- Fiji Corrections Service[110]

Fiji signed and ratified the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[111][112]

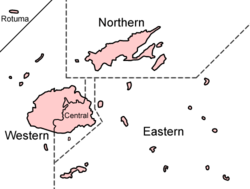

Administrative divisions

Fiji is divided into Four Major Divisions which are further divided into 14 provinces. They are:

- Central Division has 5 provinces: Naitasiri, Namosi, Rewa, Serua, and Tailevu.

- Eastern Division has 3 provinces: Kadavu, Lau, and Lomaiviti.

- Northern Division has 3 provinces: Bua, Cakaudrove, and Macuata.

- Western Division has 3 provinces: Ba, Nadroga-Navosa, and Ra.

Fiji was also divided into 3 Confederacies or Governments during the reign of Seru Epenisa Cakobau, though these are not considered political divisions, they are still considered important in the social divisions of the indigenous Fijians:

| Confederacy | Chief |

|---|---|

| Kubuna | Vacant |

| Burebasaga | Ro Teimumu Vuikaba Kepa |

| Tovata | Ratu Naiqama Tawake Lalabalavu |

Economy

Endowed with forest, mineral, and fish resources, Fiji is one of the most developed of the Pacific island economies, though still with a large subsistence sector. Some progress was experienced by this sector when Marion M. Ganey, S.J., introduced credit unions to the islands in the 1950s. Natural resources include timber, fish, gold, copper, offshore oil, and hydropower. Fiji experienced a period of rapid growth in the 1960s and 1970s but stagnated in the 1980s. The coup of 1987 caused further contraction.[113]

Economic liberalisation in the years following the coup created a boom in the garment industry and a steady growth rate despite growing uncertainty regarding land tenure in the sugar industry. The expiration of leases for sugar cane farmers (along with reduced farm and factory efficiency) has led to a decline in sugar production despite subsidies for sugar provided by the EU; Fiji has been the second largest beneficiary of sugar subsidies after Mauritius. Fiji's vital gold mining industry based in Vatukoula, which shut down in 2006, was reactivated in 2008.

Urbanisation and expansion in the service sector have contributed to recent GDP growth. Sugar exports and a rapidly growing tourist industry – with tourists numbering 430,800 in 2003[114] and increasing in the subsequent years – are the major sources of foreign exchange. Fiji is highly dependent on tourism for revenue. Sugar processing makes up one-third of industrial activity. Long-term problems include low investment and uncertain property rights. The political turmoil in Fiji in the 1980s, the 1990s, and 2000 had a severe impact on the economy, which shrank by 2.8% in 2000 and grew by only 1% in 2001.

The tourism sector recovered quickly, however, with visitor arrivals reaching pre-coup levels in 2002, resulting in a modest economic recovery which continued into 2003 and 2004 but grew by a mere 1.7% in 2005 and by 2.0% in 2006. Although inflation is low, the policy indicator rate of the Reserve Bank of Fiji was raised by 1% to 3.25% in February 2006 due to fears of excessive consumption financed by debt. Lower interest rates have so far not produced greater investment in exports.

However, there has been a housing boom due to declining commercial mortgage rates. The tallest building in Fiji is the fourteen-storey Reserve Bank of Fiji Building in Suva, which was inaugurated in 1984. The Suva Central Commercial Centre, which opened in November 2005, was planned to outrank the Reserve Bank building at seventeen stories, but last-minute design changes ensured that the Reserve Bank building remained the tallest.

Trade and investment with Fiji have been criticised due to the country's military dictatorship.[115] In 2008, Fiji's interim Prime Minister and coup leader Frank Bainimarama announced election delays and said that Fiji would pull out of the Pacific Islands Forum in Niue, where Bainimarama was to have met with Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark.[116]

The South Pacific Stock Exchange (SPSE) is the only licensed securities exchange in Fiji and is based in Suva. Its vision is to become a regional exchange.[117]

Tourism

Fiji has a significant amount of tourism with the popular regions being Nadi, the Coral Coast, Denarau Island, and Mamanuca Islands. The biggest sources of international visitors by country are Australia, New Zealand and the United States.[118] Fiji has a significant number of soft coral reefs, and scuba diving is a common tourist activity.[119]

Fiji's main attractions to tourists are primarily white sandy beaches and aesthetically pleasing islands with all-year-round tropical weather. In general, Fiji is a mid-range priced holiday/vacation destination with most of the accommodations in this range. It also has a variety of world class five-star resorts and hotels. More budget resorts are being opened in remote areas, which will provide more tourism opportunities.[119] CNN named Fiji's Laucala Island Resort as one of the fifteen world's most beautiful island hotels.[120]

Official statistics show that in 2012, 75% of visitors stated that they came for a holiday/vacation.[121] Honeymoons are very popular as are romantic getaways in general. There are also family friendly resorts with facilities for young children including kids' clubs and nanny options.[122]

Fiji has several popular tourism destinations. The Botanical Gardens of Thursten in Suva, Sigatoka Sand Dunes, and Colo-I-Suva Forest Park are three options on the mainland (Viti Levu).[123] A major attraction on the outer islands is scuba diving.[124]

According to the Fiji Bureau of Statistics, most visitors arriving to Fiji on a short-term basis are from the following countries or regions of residence:[118][125]

| Country | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 365,660 | 365,689 | 360,370 | 367,273 | |

| 198,718 | 184,595 | 163,836 | 138,537 | |

| 86,075 | 81,198 | 69,628 | 67,831 | |

| 49,271 | 48,796 | 49,083 | 40,174 | |

| 16,297 | 16,925 | 16,712 | 16,716 | |

| 13,220 | 12,421 | 11,780 | 11,709 | |

| 11,903 | 6,350 | 6,274 | 6,092 | |

| 8,176 | 8,871 | 8,071 | 6,700 | |

| Total | 870,309 | 842,884 | 792,320 | 754,835 |

Fiji has also served as a location for various Hollywood movies starting from the Mr Robinson Crusoe in 1932 to the Blue Lagoon (1980) starring Brooke Shields and Return to the Blue Lagoon (1991) with Milla Jovovich. Other popular movies shot in Fiji include Cast Away (2000) and Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid (2004).[126]

Transport

The Nadi International Airport is located 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) north of central Nadi and is the largest Fijian hub.[127] Nausori International Airport is about 23 kilometres (14 mi) northeast of downtown Suva and serves mostly domestic traffic with flights from Australia and New Zealand. The main airport in the second largest island of Vanua Levu is Labasa Airport[128] located at Waiqele, southwest of Labasa Town. The largest aircraft handled by Labasa Airport is the ATR 72. Airports Fiji Limited (AFL) is responsible for the operation of 15 public airports in the Fiji Islands. These include two international airports: Nadi international Airport, Fiji's main international gateway, and Nausori Airport, Fiji's domestic hub, and 13 outer island airports. Fiji's main airline was previously known as Air Pacific, but is now known as Fiji Airways.[129]

Fiji's larger islands have extensive bus routes that are affordable and consistent in service.[119] There are bus stops, and in rural areas buses are often simply hailed as they approach.[119] Buses are the principal form of public transport[130] and passenger movement between the towns on the main islands. Buses also serve on roll-on-roll-off inter-island ferries. Bus fares and routes are heavily regulated by the Land Transport Authority (LTA). Bus and taxi drivers hold Public Service Licenses (PSVs) issued by the LTA.

Taxis are licensed by the LTA and operate widely all over the country. Apart from urban, town-based taxis, there are others that are licensed to serve rural or semi-rural areas. The flagfall for regular taxis is F$1.50 and tariff is F$0.10 for every 200 meters.[131] For taxis that are allowed to charge Value Added Tax (VAT), the flagfall is F$1.50 and tariff is F$0.30 for the first 200 meters, and F$0.11 for every 200 meters thereafter. Taxis operating out of Fiji's international airport, Nadi charge a flagfall of F$5. The elderly and Government welfare recipients are given a 20% discount on their taxi fares.[132]

Inter-island ferries provide services between Fiji's principal islands and large vessels operate roll-on-roll-off services such as Patterson Brothers Shipping Company LTD, transporting vehicles and large amounts of cargo between the main island of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, and other smaller islands.[133]

Science and technology

Fiji is the only developing Pacific Island country with recent data for gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD). The national Bureau of Statistics cites a GERD/GDP ratio of 0.15% in 2012. Private-sector research and development (R&D) is negligible.[134]

Government investment in R&D tends to favour agriculture. In 2007, agriculture and primary production accounted for just under half of government expenditure on R&D, according to the Fijian National Bureau of Statistics. This share had risen to almost 60% by 2012. However, scientists publish much more in the field of geosciences and health than in agriculture.[134]

The rise in government spending on agricultural research has come to the detriment of research in education, which dropped to 35% of total research spending between 2007 and 2012. Government expenditure on health research has remained fairly constant, at about 5% of total government research spending, according to the Fijian National Bureau of Statistics.[134]

The Fijian Ministry of Health is seeking to develop endogenous research capacity through the Fiji Journal of Public Health, which it launched in 2012. A new set of guidelines are now in place to help build endogenous capacity in health research through training and access to new technology.[134]

Fiji is also planning to diversify its energy sector through the use of science and technology. In 2015, the Secretariat of the Pacific Community observed that, 'while Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Samoa are leading the way with large-scale hydropower projects, there is enormous potential to expand the deployment of other renewable energy options such as solar, wind, geothermal and ocean-based energy sources'.[135]

In 2014, the Centre of Renewable Energy became operational at the University of Fiji, with the assistance of the Renewable Energy in Pacific Island Countries Developing Skills and Capacity programme (EPIC) funded by the European Union. Since the programme's inception in 2013, EPIC has also developed a master's programme in renewable energy management for the University of Fiji.[134]

Society

Demographics

The 2017 census found that the population of Fiji was 884,887, compared to the population of 837,271 in the 2007 census.[7] The population density at the time of the 2007 census was 45.8 inhabitants per square kilometre. The life expectancy in Fiji was 72.1 years. Since the 1930s the population of Fiji has increased at a rate of 1.1% per year. The population is dominated by the 15–64 age segment. The median age of the population was 27.9, and the gender ratio was 1.03 males per 1 female.

Ethnic groups

The population of Fiji is mostly made up of native Fijians, who are Melanesians (54.3%), although many also have Polynesian ancestry, and Indo-Fijians (38.1%), descendants of Indian contract labourers brought to the islands by the British colonial powers in the 19th century. The percentage of the population of Indo-Fijian descent has declined significantly over the last two decades due to migration for various reasons.[136] Indo-Fijians suffered reprisals for a period after the Fiji coup of 2000.[137][138] There is also a small but significant group of descendants of indentured labourers from the Solomon Islands.

About 1.2% are Rotuman — natives of Rotuma Island, whose culture has more in common with countries such as Tonga or Samoa than with the rest of Fiji. There are also small but economically significant groups of Europeans, Chinese, and other Pacific island minorities. The membership of other ethnic groups is about 4.5%.[139] 3,000 people or 0.3% of the people living in Fiji are from Australia.[140]

Relationships between ethnic Fijians and Indo-Fijians in the political arena have often been strained, and the tension between the two communities has dominated politics in the islands for the past generation. The level of political tension varies among different regions of the country.[141]

Family groups

The concept of family and community is of great importance to Fijian culture. Within the indigenous (iTaukei) communities many members of the extended family will adopt particular titles and roles of direct guardians. Kinship is determined through a child's lineage to a particular spiritual leader, so that a clan is based on traditional customary ties as opposed to actual biological links. These clans, based on the spiritual leader, are known as a matangali. Within the matangali are a number of smaller collectives, known as the mbito. The descent is patrilineal, and all the status is derived from the father's side.[142]

Demonym

Within Fiji, many argue that the term Fijian refers solely to indigenous Fijians: it denotes an ancestral ethnicity, not a nationality. Constitutionally, citizens of Fiji were previously referred to as "Fiji Islanders" though the term Fiji Nationals was used for official purposes. However, the current constitution refers to all Fijian citizens as "Fijians".[143] In August 2008, shortly before the proposed People's Charter for Change, Peace and Progress was due to be released to the public, it was announced that it recommended a change in the name of Fiji's citizens. If the proposal were adopted, all citizens of Fiji, whatever their ethnicity, would be called "Fijians". The proposal would change the English name of indigenous Fijians from "Fijians" to itaukei, the Fijian language endonym for indigenous Fijians.[144]

Deposed Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase reacted by stating that the name "Fijian" belonged exclusively to indigenous Fijians, and that he would oppose any change in legislation enabling non-indigenous Fijians to use it.[145] The Methodist Church, to which a large majority of indigenous Fijians belong, also reacted strongly to the proposal, stating that allowing any Fiji citizen to call themselves "Fijian" would be "daylight robbery" inflicted on the indigenous population.[146]

In an address to the nation during the constitutional crisis of April 2009, military leader and interim Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama, who has been at the forefront of the attempt to change the definition of "Fijian", stated:

I know we all have our different ethnicities, our different cultures and we should, we must, celebrate our diversity and richness. However, at the same time we are all Fijians. We are all equal citizens. We must all be loyal to Fiji; we must be patriotic; we must put Fiji first.[147]

_(2).jpg)

In May 2010, Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum reiterated that the term "Fijian" should apply to all Fiji nationals, but the statement was again met with protest. A spokesperson for the Viti Landowners and Resource Owners Association claimed that even fourth-generation descendants of migrants did not fully understand "what it takes to be a Fijian", and added that the term refers to a legal standing, since legislation affords specific rights to "Fijians" (meaning, in legislation, indigenous Fijians).[148] Fiji academic Brij Lal, although a prominent critic of the Bainimarama government,[149][150] said he "would not be surprised" if the new definition of the word "Fijian" were included in the government's projected new Constitution, and that he personally saw "no reason the term Fijian should not apply to everyone from Fiji".[151]

Languages

Fiji has three official languages under the 1997 constitution (and not revoked by the 2013 Constitution): English, iTaukei (Fijian) and (Fiji) Hindi.

Fijian is an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian family spoken in Fiji. It has 350,000 first-language speakers, which is less than half the population of Fiji, but another 200,000 speak it as a second language. The 1997 Constitution established Fijian as an official language of Fiji, along with English and Fiji Hindi.[152] Fijian is a VOS language.

The Fiji Islands developed many dialects, which may be classified in two major branches—eastern and western. Missionaries in the 1840s chose an Eastern dialect, the speech of Bau Island off the southeast coast of the main island of Viti Levu, to be the written standard of the Fijian language. Bau Island was home to Seru Epenisa Cakobau, the chief who eventually became the self-proclaimed King of Fiji.

| English | hello/hi | good morning | goodbye |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fijian[153] | bula | yadra (pronounced yandra) | moce (pronounced mothe) |

| Fiji Hindi | नमस्ते (namaste) | सुप्रभात (suprabhat) | अलविदा (alavidā) |

Religion

According to the 2007 census, 64.4% of the population at the time was Christian, while 27.9% was Hindu, 6.3% Muslim, 0.8% non-religious, 0.3% Sikh, and the remaining 0.3% belonged to other religions.[5] Among Christians, 54% were counted as Methodist, followed by 14.2% Catholic, 8.9% Assemblies of God, 6.0% Seventh-day Adventist, 1.2% Anglican with the remaining 16.1% belonging to other denominations.[5]