Cook Islands

The Cook Islands (Cook Islands Māori: Kūki 'Āirani)[6] is a self-governing island country in the South Pacific Ocean in free association with New Zealand. It comprises 15 islands whose total land area is 240 square kilometres (93 sq mi). The Cook Islands' Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers 1,960,027 square kilometres (756,771 sq mi) of ocean.[7]

Cook Islands Kūki 'Āirani | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Avarua 21°12′S 159°46′W |

| Official languages |

|

| Spoken languages |

|

| Ethnic groups (2016 census[2]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Cook Islander |

| Government | Unitary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Tom Marsters | |

| Henry Puna | |

| Tou Travel Ariki | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Associated state of New Zealand | |

| 4 August 1965 | |

• UN recognition of independence in foreign relations | 1992[3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 236.7 km2 (91.4 sq mi) (unranked) |

| Population | |

• 2016 census | 17,459[4] |

• Density | 42/km2 (108.8/sq mi) (138th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate |

• Total | $311 million[5] (not ranked) |

• Per capita | $15,002.5 (not ranked) |

| Currency | New Zealand dollar (NZD)Cook Islands dollar |

| Time zone | UTC-10 (CKT) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +682 |

| ISO 3166 code | CK |

| Internet TLD | .ck |

| |

New Zealand is responsible for the Cook Islands' defence and foreign affairs, but these responsibilities are exercised in consultation with the Cook Islands.[8] In recent times, the Cook Islands have adopted an increasingly independent foreign policy.[9] Cook Islanders are citizens of New Zealand, but they also have the status of Cook Islands nationals, which is not given to other New Zealand citizens. The Cook Islands has been an active member of the Pacific Community since 1980.

The Cook Islands' main population centres are on the island of Rarotonga (13,007 in 2016),[10] where there is an international airport. There is also a larger population of Cook Islanders in New Zealand itself: in the 2013 census, 61,839 people said they were Cook Islanders, or of Cook Islands descent.[11]

With over 168,000 visitors travelling to the islands in 2018,[12] tourism is the country's main industry, and the leading element of the economy, ahead of offshore banking, pearls, and marine and fruit exports.

History

The latest carbon-dating evidence reveals that the Cook Islands were first settled by around AD 1000 by Polynesian people who are thought to have migrated from Tahiti,[13] an island 1,154 kilometres (717 mi) to the northeast of the main island of Rarotonga.

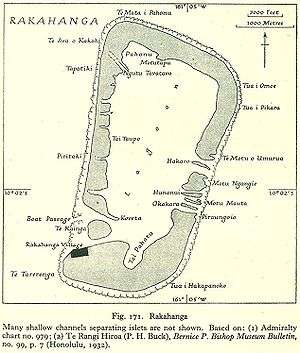

Spanish ships visited the islands in the 16th century. The first written record came in 1595 when the island of Pukapuka was sighted by Spanish sailor Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira, who gave it the name San Bernardo (Saint Bernard). Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, a Portuguese captain working for the Spanish crown, made the first recorded European landing in the islands when he set foot on Rakahanga in 1606, calling the island Gente Hermosa (Beautiful People).[14]

British navigator Captain James Cook arrived in 1773 and again in 1777[15] giving the island of Manuae the name Hervey Island. The Hervey Islands later came to be applied to the entire southern group. The name "Cook Islands", in honour of Cook, first appeared on a Russian naval chart published in the 1820s.[16]

In 1813 John Williams, a missionary on the Endeavour (not the same ship as Cook's) made the first recorded sighting of Rarotonga.[17] The first recorded landing on Rarotonga by Europeans was in 1814 by the Cumberland; trouble broke out between the sailors and the Islanders and many were killed on both sides.[18] The islands saw no more Europeans until English missionaries arrived in 1821. Christianity quickly took hold in the culture and many islanders are Christians today.

The islands were a popular stop in the 19th century for whaling ships from the United States, Britain and Australia. They visited, from at least 1826, to obtain water, food, and firewood.[19] Their favourite islands were Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia and Penrhyn.

The Cook Islands became a British protectorate in 1888, largely because of community fears that France might occupy the islands as it already had Tahiti. On 6 September 1900, the islanders' leaders presented a petition asking that the islands (including Niue "if possible") be annexed as British territory.[20][21] On 8 and 9 October 1900, seven instruments of cession of Rarotonga and other islands were signed by their chiefs and people. A British Proclamation was issued, stating that the cessions were accepted and the islands declared parts of Her Britannic Majesty's dominions.[20] However, it did not include Aitutaki. Even though the inhabitants regarded themselves as British subjects, the Crown's title was unclear until the island was formally annexed by that Proclamation.[22][23] In 1901 the islands were included within the boundaries of the Colony of New Zealand by Order in Council[24] under the Colonial Boundaries Act, 1895 of the United Kingdom.[20][25] The boundary change became effective on 11 June 1901, and the Cook Islands have had a formal relationship with New Zealand since that time.[20]

When the British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948 came into effect on 1 January 1949, Cook Islanders who were British subjects automatically gained New Zealand citizenship.[26] The islands remained a New Zealand dependent territory until the New Zealand Government decided to grant them self-governing status. On 4 August 1965, a constitution was promulgated. The first Monday in August is celebrated each year as Constitution Day.[27] Albert Henry of the Cook Islands Party was elected as the first Premier. Henry led the nation until 1978, when he was accused of vote-rigging and resigned. He was succeeded by Tom Davis of the Democratic Party.

In March 2019, it was reported that the Cook Islands had plans to change its name and remove the reference to Captain James Cook in favour of "a title that reflects its 'Polynesian nature'".[28][29] It was later reported in May 2019 that the proposed name change had been poorly received by the Cook Islands diaspora. As a compromise, it was decided that the English name of the islands would not be altered, but that a new Cook Islands Māori name would be adopted to replace the current name, a transliteration from English.[30] Discussions over the name continued in 2020.[31]

Geography

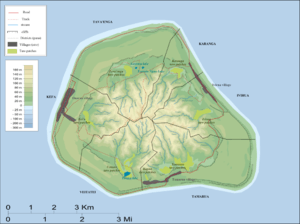

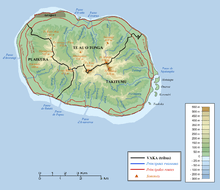

The Cook Islands are in the South Pacific Ocean, northeast of New Zealand, between French Polynesia and American Samoa. There are 15 major islands spread over 2,200,000 km2 (850,000 sq mi) of ocean, divided into two distinct groups: the Southern Cook Islands and the Northern Cook Islands of coral atolls.[32]

The islands were formed by volcanic activity; the northern group is older and consists of six atolls, which are sunken volcanoes topped by coral growth. The climate is moderate to tropical. The Cook Islands consist of 15 islands and two reefs. From March to December, the Cook Islands are in the path of tropical cyclones, the most famous of which are Martin and Percy.[33]

| Group | Island | Area km² |

Population | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

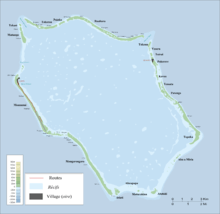

| Northern | Penrhyn | 10 | 226 | 22.6 |

| Northern | Rakahanga | 4 | 80 | 20.0 |

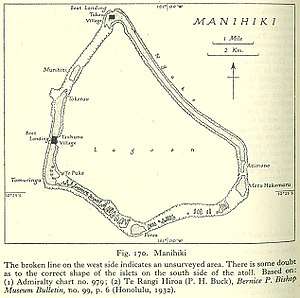

| Northern | Manihiki | 5 | 213 | 42.6 |

| Northern | Pukapuka | 1 | 444 | 444.0 |

| Northern | Tema Reef (submerged) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Northern | Nassau | 1 | 78 | 78.0 |

| Northern | Suwarrow | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Southern | Palmerston | 2 | 58 | 28.0 |

| Southern | Aitutaki | 18 | 1,928 | 107.1 |

| Southern | Manuae | 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Southern | Takutea | 1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Southern | Mitiaro | 22 | 155 | 7.1 |

| Southern | Atiu | 27 | 437 | 16.2 |

| Southern | Mauke | 18 | 297 | 16.5 |

| Southern | Winslow Reef (submerged) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Southern | Rarotonga | 67 | 13,044 | 194.7 |

| Southern | Mangaia | 52 | 499 | 9.6 |

| Total | Total | 237 | 17,459 | 73.7 |

The table is ordered from north to south. Population figures from the 2016 census.[34]

Politics and foreign relations

.jpg)

The Cook Islands is a representative democracy with a parliamentary system in an associated state relationship with New Zealand. Executive power is exercised by the government, with the Chief Minister as head of government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Parliament of the Cook Islands. There is a pluriform multi-party system. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. The head of state is the Queen of New Zealand, who is represented in the Cook Islands by the Queen's Representative.[35]

The islands are self-governing in "free association" with New Zealand. New Zealand retains primary responsibility for external affairs, with consultation with the Cook Islands government. Cook Islands nationals are citizens of New Zealand and can receive New Zealand government services, but the reverse is not true; New Zealand citizens are not Cook Islands nationals. Despite this, as of 2014, the Cook Islands had diplomatic relations in its own name with 43 other countries. The Cook Islands is not a United Nations member state, but, along with Niue, has had their "full treaty-making capacity" recognised by United Nations Secretariat,[36][37] and is a full member of the WHO and UNESCO UN specialised agencies, is an associate member of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) and a Member of the Assembly of States of the International Criminal Court.

On 11 June 1980, the United States signed a treaty with the Cook Islands specifying the maritime border between the Cook Islands and American Samoa and also relinquishing any American claims to Penrhyn, Pukapuka, Manihiki, and Rakahanga.[38] In 1990 the Cook Islands and France signed a treaty that delimited the boundary between the Cook Islands and French Polynesia.[39] In late August 2012, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited the islands. In 2017, the Cook Islands signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[40]

Human rights

Male homosexuality is illegal in the Cook Islands and is punishable by a maximum term of seven years imprisonment.[41]

Administrative subdivisions

There are island councils on all of the inhabited outer islands (Outer Islands Local Government Act 1987 with amendments up to 2004, and Palmerston Island Local Government Act 1993) except Nassau, which is governed by Pukapuka (Suwarrow, with only one caretaker living on the island, also governed by Pukapuka, is not counted with the inhabited islands in this context). Each council is headed by a mayor.

|

|

Aitutaki (including uninhabited Manuae) |

|

|

Atiu (including uninhabited Takutea) |

|

Mangaia | |

|

|

Manihiki |

|

|

Ma'uke |

|

|

Mitiaro |

|

|

Palmerston |

|

|

Penrhyn |

|

Pukapuka (including Nassau and Suwarrow) | |

|

|

Rakahanga |

The three Vaka councils of Rarotonga established in 1997 (Rarotonga Local Government Act 1997), also headed by mayors,[42] were abolished in February 2008, despite much controversy.[43][44]

| Te-Au-O-Tonga | (equivalent to Avarua, the capital of the Cook Islands) |

| Puaikura | Arorangi |

| Takitumu | Matavera, Ngatangiia, Takitumu |

On the lowest level, there are village committees. Nassau, which is governed by Pukapuka, has an island committee (Nassau Island Committee), which advises the Pukapuka Island Council on matters concerning its own island.

Demographics

| Population pyramid 2011[45] | ||||

| % | Males | Age | Females | % |

| 0 | 85+ | 0 | ||

| 0.5 | 80–84 | 0.6 | ||

| 0.7 | 75–79 | 0.9 | ||

| 1.4 | 70–74 | 1.4 | ||

| 1.9 | 65–69 | 1.8 | ||

| 2.2 | 60–64 | 2 | ||

| 2.4 | 55–59 | 2.4 | ||

| 3 | 50–54 | 3 | ||

| 3.6 | 45–49 | 3.6 | ||

| 3.4 | 40–44 | 3.6 | ||

| 3.1 | 35–39 | 3.6 | ||

| 3 | 30–34 | 3.3 | ||

| 3.3 | 25–29 | 3.8 | ||

| 3.4 | 20–24 | 3.7 | ||

| 4.3 | 15–19 | 4.1 | ||

| 4.5 | 10–14 | 4 | ||

| 4.3 | 5–9 | 4.3 | ||

| 4.5 | 0–4 | 4.4 | ||

Births and deaths[46]

| Year | Population | Live births | Deaths | Natural increase | Crude birth rate | Crude death rate | Rate of natural increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 284 | 72 | 212 | 12.6 | 3.2 | 9.4 | |

| 2010 | 286 | 92 | 194 | 12.1 | 3.9 | 8.2 | |

| 2011 | 14,974 | 262 | 72 | 190 | 13.6 | 3.7 | 9.8 |

| 2012 | 259 | 104 | 155 | 13.3 | 5.3 | 7.9 | |

| 2013 | 256 | 115 | 141 | 13.8 | 6.2 | 7.6 | |

| 2014 | 204 | 113 | 11.0 | 6.1 | 4.9 | ||

| 2015 | 205 | 102 | 11.0 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

Religion

In the Cook Islands the Church is separate from the state, and most of the population is Christian.[47] The religious distribution is as follows:

The various Protestant groups account for 62.8% of the believers, the most followed denomination being the Cook Islands Christian Church with 49.1%. Other Protestant Christian groups include Seventh-day Adventist 7.9%, Assemblies of God 3.7% Apostolic Church 2.1%. The main non-Protestant group is Roman Catholics with 17% of the population. While Mormons make up 4.4%.[47]

Economy

The economy is strongly affected by geography. It is isolated from foreign markets, and has some inadequate infrastructure; it lacks major natural resources, has limited manufacturing and suffers moderately from natural disasters.[48] Tourism provides the economic base that makes up approximately 67.5% of GDP. Additionally, the economy is supported by foreign aid, largely from New Zealand. China has also contributed foreign aid, which has resulted in, among other projects, the Police Headquarters building. The Cook Islands is expanding its agriculture, mining and fishing sectors, with varying success.

Since approximately 1989, the Cook Islands have become a location specialising in so-called asset protection trusts, by which investors shelter assets from the reach of creditors and legal authorities.[49][50] According to The New York Times, the Cooks have "laws devised to protect foreigners' assets from legal claims in their home countries", which were apparently crafted specifically to thwart the long arm of American justice; creditors must travel to the Cook Islands and argue their cases under Cooks law, often at prohibitive expense.[49] Unlike other foreign jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands and Switzerland, the Cooks "generally disregard foreign court orders" and do not require that bank accounts, real estate, or other assets protected from scrutiny (it is illegal to disclose names or any information about Cooks trusts) be physically located within the archipelago.[49] Taxes on trusts and trust employees account for some 8% of the Cook Islands economy, behind tourism but ahead of fishing.[49]

In recent years, the Cook Islands has gained a reputation as a debtor paradise, through the enactment of legislation that permits debtors to shield their property from the claims of creditors.[49]

Culture

Language

The languages of the Cook Islands include English, Cook Islands Māori (or "Rarotongan"), and Pukapukan. Dialects of Cook Islands Maori include Penrhyn; Rakahanga-Manihiki; the Ngaputoru dialect of Atiu, Mitiaro, and Mauke; the Aitutaki dialect; and the Mangaian dialect. Cook Islands Maori and its dialectic variants are closely related to both Tahitian and to New Zealand Māori. Pukapukan is considered closely related to the Samoan language. English and Cook Islands Māori are official languages of the Cook Islands; per the Te Reo Maori Act. The legal definition of Cook Islands Māori includes Pukapukan.[51]

Music

Music in the Cook Islands is varied, with Christian songs being quite popular, but traditional dancing and songs in Polynesian languages remain popular.

.jpg)

Public holidays

Art

Carving

Woodcarving is a common art form in the Cook Islands. The proximity of islands in the southern group helped produce a homogeneous style of carving but that had special developments in each island. Rarotonga is known for its fisherman's gods and staff-gods, Atiu for its wooden seats, Mitiaro, Mauke and Atiu for mace and slab gods and Mangaia for its ceremonial adzes. Most of the original wood carvings were either spirited away by early European collectors or were burned in large numbers by missionaries. Today, carving is no longer the major art form with the same spiritual and cultural emphasis given to it by the Maori in New Zealand. However, there are continual efforts to interest young people in their heritage and some good work is being turned out under the guidance of older carvers. Atiu, in particular, has a strong tradition of crafts both in carving and local fibre arts such as tapa. Mangaia is the source of many fine adzes carved in a distinctive, idiosyncratic style with the so-called double-k design. Mangaia also produces food pounders carved from the heavy calcite found in its extensive limestone caves.[53]

Weaving

The outer islands produce traditional weaving of mats, basketware and hats. Particularly fine examples of rito hats are worn by women to church. They are made from the uncurled immature fibre of the coconut palm and are of very high quality. The Polynesian equivalent of Panama hats, they are highly valued and are keenly sought by Polynesian visitors from Tahiti. Often, they are decorated with hatbands made of minuscule pupu shells that are painted and stitched on by hand. Although pupu are found on other islands the collection and use of them in decorative work has become a speciality of Mangaia. The weaving of rito is a speciality of the northern islands, Manihiki, Rakahanga and Penrhyn.[54]

Tivaevae

A major art form in the Cook Islands is tivaevae. This is, in essence, the art of handmade Island scenery patchwork quilts. Introduced by the wives of missionaries in the 19th century, the craft grew into a communal activity, which is probably one of the main reasons for its popularity.[55]

Contemporary art

The Cook Islands has produced internationally recognised contemporary artists, especially in the main island of Rarotonga. Artists include painter (and photographer) Mahiriki Tangaroa, sculptors Eruera (Ted) Nia (originally a film maker) and master carver Mike Tavioni, painter (and Polynesian tattoo enthusiast) Upoko'ina Ian George, Aitutakian-born painter Tim Manavaroa Buchanan, Loretta Reynolds, Judith Kunzlé, Joan Rolls Gragg, Kay George (who is also known for her fabric designs), Apii Rongo, Varu Samuel, and multi-media, installation and community-project artist Ani O'Neill, all of whom currently live on the main island of Rarotonga. Atiuan-based Andrea Eimke is an artist who works in the medium of tapa and other textiles, and also co-authored the book 'Tivaivai – The Social Fabric of the Cook Islands' with British academic Susanne Kuechler. Many of these artists have studied at university art schools in New Zealand and continue to enjoy close links with the New Zealand art scene.[56]

New Zealand-based Cook Islander artists include Michel Tuffery, print-maker David Teata, Richard Shortland Cooper, Sylvia Marsters and Jim Vivieaere.

On Rarotonga, the main commercial galleries are Beachcomber Contemporary Art (Taputapuatea, Avarua) run by Ben & Trevon Bergman,[57] and The Art Studio Gallery (Arorangi) run by Ian and Kay George.[58] The Cook Islands National Museum also exhibits art.[59]

Wildlife

- The national flower of the Cook Islands is the Tiare māori or Tiale māoli (Penrhyn, Nassau, Pukapuka).[60]

- The Cook Islands have a large non-native population of Ship rat[61] and Kiore toka (Polynesian rat).[62] The rats have dramatically reduced the bird population on the islands.[63]

- In April 2007, 27 Kuhl's lorikeet were re-introduced to Atiu from Rimatara. Fossil and oral traditions indicate that the species was formerly on at least five islands of the southern group. Excessive exploitation for its red feathers is the most likely reason for the species's extinction in the Cook Islands.[64]

Sport

Rugby league is the most popular sport in the Cook Islands.[65]

See also

References

- "Cook Islands". www.cia.gov. The World Factbook.

- "Census of Population & Dwellings 2016 Results". Ministry of Finance & Economic Management. 2016. Table 2: Social Characteristics - Sheet 2.3.

- UN THE WORLD TODAY (PDF) and Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs Supplement No. 8; page 10 Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Census 2016 - Cook Islands - Ministry of Finance and Economic Management". www.mfem.gov.ck. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "UN Data". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Cook Islands Maori dictionary by Jasper Buse & Raututi Taringa, Cook Islands Ministry of Education (1995) page 200

- Fisheries, Ecosystems and Biodiversity. Sea Around Us

- "Cook Islands push for independence from NZ". Stuff.co.nz. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Cook Islands". France in New Zealand. 13 March 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

Since 2001, the Cook Islands have complete sovereignty in managing their Foreign affairs according to the common declaration of 6 April 2001.

- "Census 2016 - Cook Islands - Ministry of Finance and Economic Management". www.mfem.gov.ck. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "2013 Census ethnic group profiles". Statistics NZ. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Cook Islands welcome more visitors". Radio New Zealand. February 2019. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019.

- Crowe, Andrew (2018). Pathway of the Birds: The Voyaging Achievements of Māori and their Polynesian Ancestors. Auckland: David Bateman Ltd. p. 122.

- Hooker, Brian (1998). "European discovery of the Cook Islands". Terrae Incognitae. 30 (1): 54–62. doi:10.1179/tin.1998.30.1.54.

- Thomas, Nicholas (2003). Cook : the extraordinary voyages of Captain James Cook, Walker & Company, ISBN 0802714129, pp. 310–311.

- "Cook Islands Government website". Cook-islands.gov.ck. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Ten Decades: The Australasian Centenary History of the London Missionary Society, Rev. Joseph King (Word document)". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "History of the Cook Islands". Ck/history. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Robert Langdon (ed.) Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, (1984) Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, pp16 & 24.

- "Commonwealth and Colonial Law" by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. P. 891

- N.Z. Parliamentary Pp., A3 (1901)

- "Commonwealth and Colonial Law" by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. P. 761

- N.Z. Parliamentary Pp., A1 (1900)

- S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. XVI, 862–863

- 58 & 59 V. c. 34.

- 3. Aliens and citizens – Citizenship – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Teara.govt.nz (4 March 2009). Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Australia - Oceania :: Cook Islands — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- "Cook Islands to choose new indigenous name and remove any association with British explorer". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 6 March 2019 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "Cook Islands government backs name change body". Radio New Zealand. 5 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Cook Islands: Backlash over name change leads to compromise traditional name". Pacific Beat with Catherine Graue. ABC News. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "Renewed calls for the Cook Islands to take on indigenous name". RNZ. 2 July 2020.

- "Cook Islands Travel Guide" (with description), World Travel Guide, Nexus Media Communications, 2006. Webpage: WTGuide-Cook-Islands Archived 26 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Cook Islands climate: average weather, temperature, precipitation, best time". www.climatestotravel.com. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Cook Islands Ministry of Finance and Economic Management, 2016 Census". Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "Cook Islands System of Government Information". www.paclii.org. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Repertory of Practice" (PDF), Legal.un.org, p. 10, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013

- "The World today" (PDF), Legal.un.org

- "Treaty Between the United States of America and the Cook Islands on Friendship and Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary Between the United States of America and the Cook Islands (and Exchange of Notes)". Pacific Islands Treaty Series. University of the South Pacific School of Law. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- "Agreement on Maritime Delimitation Between the Government of the Cook Islands and the Government of the French Republic". Pacific Islands Treaty Series. University of the South Pacific School of Law. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Larmour, Peter and Barcham, Manuhuia. Cook Islands 2004, Transparency International Country Study Report.

- "Rarotonga Local Government (Repeal) Bill To Be Tabled, Cook Islands Government". Cook-islands.gov.ck. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Minister asked to answer queries over abolition of Vaka Councils. The Cook Islands Herald, No. 393 (9 February 2008)

- "Demographic Yearbook, Population by age, sex and urban/rural residence: latest available year, 2005–2014" (PDF). UN Data. United Nations. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- "United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics". Unstats.un.org. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Australia - Oceania :: Cook Islands — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Polynesia French Business Law Handbook: Strategic Information and Laws ISBN 1-4387-7081-2 p. 130

- Wayne, Leslie (14 December 2013). "Cook Islands, a Paradise of Untouchable Assets". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- Rosen, Howard; Donlevy-Rosen, Patricia. "Review of Offshore Jurisdictions: Cook Islands". The Asset Protection News.

- "Cook Islands". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Standing male figure – Google Arts & Culture". Google.com. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Lords of the Dance : Culture of the Cook Islands". Ck. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Lords of the Dance : Culture of the Cook Islands". Ck. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Tivaevae – Quilts of the Cook Islands". Ck. 15 July 2004. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "The Cook Islands Arts Community". Cookislandsarts.com. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "BCA Gallery, Beachcomber Art, Rarotonga Art, Cook Islands Art, Pacifc Art, South Pacific Art". Gallerybca.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Ian George – Tautai – Guiding Pacific Artstautai – Guiding Pacific Arts". TAUTAI. 20 June 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Cook Islands Museum and Library Society | Official Website of the Cook Islands Library & Museum Society". Cook-islands-library-museum.org. 22 December 1964. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Cook Islands Wildlife". Govisitcookislands.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007.

- "Cook Islands Biodiversity: Rattus rattus – Ship Rat". Cookislands.bishopmuseum.org. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Cook Islands Biodiversity: Rattus exulans – Pacific Rat". Cookislands.bishopmuseum.org. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Cook Islands Biodiversity: The Status of Cook Islands Birds – 1996". Cookislands.bishopmuseum.org. 24 September 2005. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "BirdLife International: Rimatara Lorikeet (Vini kuhlii) at". Birdlife.org. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Cook Islands Financial Strife". We Are Rugby. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011.

Further reading

- Gilson, Richard. The Cook Islands 1820–1950. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-7055-0735-1

External links

- Official website Cook Islands Government

- Cook Islands News – daily newspaper

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- "Cook Islands". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Cook Islands from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Cook Islands at Curlie

.svg.png)