Hindu Kush

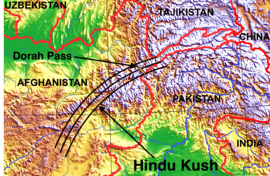

The Hindu Kush (Dari, Urdu: هندوکش /kʊʃ, kuːʃ/;commonly understood to mean Hindu killers or killer of the Hindus in Persian;[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]) is an 800-kilometre-long (500 mi) mountain range that stretches through Afghanistan,[9][10] from its centre to Northern Pakistan and into Tajikistan.

| Hindu Kush | |

|---|---|

Topography of the Hindu Kush range[1]

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Tirich Mir (Pakistan) |

| Elevation | 7,708 m (25,289 ft) |

| Coordinates | 36°14′45″N 71°50′38″E |

| Geography | |

| Countries | |

| Region | East-South-Central Asia |

| Parent range | Himalayas |

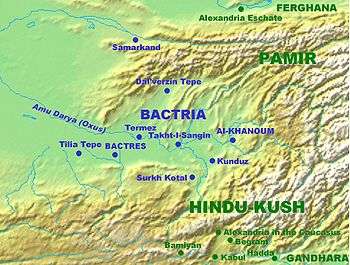

The range forms the western section of the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region (HKH)[11][12][13] and is the westernmost extension of the Pamir Mountains, the Karakoram and the Himalayas. It divides the valley of the Amu Darya (the ancient Oxus) to the north from the Indus River valley to the south. The range has numerous high snow-capped peaks, with the highest point being Tirich Mir or Terichmir at 7,708 metres (25,289 ft) in the Chitral District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. To the north, near its northeastern end, the Hindu Kush buttresses the Pamir Mountains near the point where the borders of China, Pakistan and Afghanistan meet, after which it runs southwest through Pakistan and into Afghanistan near their border.[9] The eastern end of the Hindu Kush in the north merges with the Karakoram Range.[14][15] Towards its southern end, it connects with the Spin Ghar Range near the Kabul River.[16][17]

The Hindu Kush range region was a historically significant centre of Buddhism with sites such as the Bamiyan Buddhas.[18][19] It remained a stronghold of polytheistic faiths until the 19th century.[20] The range and communities settled in it hosted ancient monasteries, important trade networks and travellers between Central Asia and South Asia.[21][22] The Hindu Kush range has also been the passageway during the invasions of the Indian subcontinent,[23][24] and continues to be important during modern-era warfare in Afghanistan.[25][26]

Etymology

In the time of Alexander the Great, the Hindu Kush range was referred to as the Caucasus Indicus or the "Caucasus of the Indus River" (as opposed to the Greater Caucasus range between the Caspian and Black Seas). The mountain range was called "Paropamisadae" by Hellenic Greeks in the late first millennium BC.[27] The earliest known usage of the name Hindu Kush occurs on a map published about 1000 CE.[28] The name was sometimes applied to the entire range separating the basins of the Kabul and Helmand Rivers from that of the Amu Darya, or, more specifically, to that part of the range lying northwest of Kabul.

A Persian-English dictionary[29] indicates that the suffix 'koš' [koʃ] is the present stem of the verb "to kill" ('koštan' کشتن). According to Francis Joseph Steingass, the word and suffix "-kush" means "a male; (imp. of kushtan in comp.) a killer, who kills, slays, murders, oppresses as azhdaha-kush".[30] According to one interpretation, the name Hindu Kush means "kills the Hindu" or "Hindu killer" and is a reminder of the days when slaves from the Indian subcontinent died in the harsh weather typical of the Afghan mountains while being taken to Central Asia.[31][32][33] Another theory suggest it means "killed of Indians," rather than "Killer of Hindus."[34] The World Book Encyclopedia states that the word kush means death, and was probably given to the mountains because of their dangerous passes.[35]

In his travel memoirs about India, the 14th century Moroccan traveller Muhammad Ibn Battuta mentioned crossing into India via the mountain passes of the Hindu Kush. In his Rihla, he mentions these mountains and the history of the range in slave trading.[36][22] Alexander von Humboldt stated that it can be learned from his work that the name only referred to a single mountain pass upon which many Indian slaves died of the cold weather.[37] Battuta wrote,

After this I proceeded to the city of Barwan, in the road to which is a high mountain, covered with snow and exceedingly cold; they call it the Hindu Kush, that is Hindu-slayer, because most of the slaves brought thither from India die on account of the intenseness of the cold.

Though the first recorded use of the name dates from 1000 CE,[28] Ervin Grötzbacht in he Encyclopædia Iranica says the name "missing from the accounts of the early Arab geographers and occurs for the first time in Ibn Baṭṭuṭa (ca. 1330)".[38] Ibn Baṭṭuṭa, states Grötzbach, saw the "origin of the name Hindu Kush (Hindu-killer) in the fact that numerous Hindu slaves died crossing the pass on their way from India to Turkestan".[39]

Alternate theories

The origins of the name Hindu Kush is subject to various other theories being propounded.[31] According to Hobson-Jobson, the name might be a possible corruption of Indicus Caucasus, with another explanation mentioned first by Ibn Batuta remaining popular despite doubts upon it, and the modification of the name by some later writers into Hindu Koh is factitious and reveals nothing on the name's origin.[40]

According to Allan, the term Hindu Kush has been commonly seen to mean "Hindu killer", but two other meanings of the term include "sparkling snows of India" and "mountains of India" with "Kush" possibly a soft variant of Kuh which means "mountain". nother theory suggests the word "Hindu" in Hindu Kush is derived from the same root as "sindhu," meaning river, while Kush is a variant of the Persian word for mountain.[41] Hindu Kush in Arabic means mountains of India. To Arab geographers, states Allan, Hindu Kush was the frontier boundary where Hindustan started.[42][28]

According to McColl, the origins of the Hindu Kush name are controversial. Along with its origin in the perishing of Indian slaves, two other possibilities exist.[43] The term could be a corruption of Hindu Koh from pre-Islamic times where it separated Hindu population of southern Afghanistan from non-Hindu population in northern Afghanistan. The second possibility is that the name may be from the ancient Avestan language, with the meaning "water mountain." [43]

In Persian "Kush" (now pronounced “Kosh”) means 'an opening'. Hindustan began after crossing the Hindu Kush mountain range, which is why they called it "Hindu Kush" (cf. Mushkil-Kusha, which means “solving the difficulty”). "Kush" and its modern variation "Kosh" mean "opening", "Kash" means crushing or killing.

Other names

The mountain range was also called "Paropamisadae" by Hellenic Greeks in the late first millennium BC.[27]

Some 19th century encyclopaedias and gazetteers state that the term Hindu Kush originally applied only to the peak in the area of the Kushan Pass, which had become a centre of the Kushan Empire by the first century.[44] Some scholars remove the space, and refer to Hindu Kush as "Hindukush".[45][46]

Geography

The range forms the western section of the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region (HKH)[11][12][13] and is the westernmost extension of the Pamir Mountains, the Karakoram and the Himalayas. It divides the valley of the Amu Darya (the ancient Oxus) to the north from the Indus River valley to the south. The range has numerous high snow-capped peaks, with the highest point being Tirich Mir or Terichmir at 7,708 metres (25,289 ft) in the Chitral District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. To the north, near its northeastern end, the Hindu Kush buttresses the Pamir Mountains near the point where the borders of China, Pakistan and Afghanistan meet, after which it runs southwest through Pakistan and into Afghanistan near their border.[9] The eastern end of the Hindu Kush in the north merges with the Karakoram Range.[14][15] Towards its southern end, it connects with the Spin Ghar Range near the Kabul River.[16][17]

Watershed

The Hindu Kush form the boundary between the Indus watershed in South Asia, and Amu Darya watershed in Central Asia.[47] Melt water from snow and ice feeds major river systems in Central Asia: the Amu Darya, Helmand River (which is a major source of water for the Sistan Basin in southern Afghanistan and Iran), and the Kabul River[47] - the last of which is a major tributary of the Indus River. Smaller rivers with headwaters in the range include them Khash, the Farah and the Arashkan (Harut) rivers. The basins of these rivers serves the ecology and economy of the region, but the water flow in these rivers greatly fluctuate, and reliance on these has been a historical problem with extended droughts being commonplace.[48] The eastern end of the range, with the highest peaks, high snow accumulation allows to long-term water storage.[49]

Climate zones

These mountainous areas are mostly barren, or at the most sparsely sprinkled with trees and stunted bushes. From about 1,300 to 2,300 m (4,300 to 7,500 ft), states Yarshater, "sklerophyllous forests are predominant with Quercus and Olea (wild olive); above that up to a height of about 3,300 m (10,800 ft) one finds coniferous forests with cedars, Picea, Abies, Pinus, and junipers". The inner valleys of the Hindu Kush see little rain and have desert vegetation.[50]

Geology

Geologically, the range is rooted in the formation of a subcontinent from a region of Gondwana that drifted away from East Africa about 160 million years ago, around the Middle Jurassic period.[52][53] The Indian subcontinent, Australia and islands of the Indian Ocean rifted further, drifting northeastwards, with the Indian subcontinent colliding with the Eurasian Plate nearly 55 million years ago, towards the end of Palaeocene.[52] This collision created the Himalayas, including the Hindu Kush.[54]

The Hindu Kush are a part of the "young Eurasian mountain range consisting of metamorphic rocks such as schist, gneiss and marble, as well as of intrusives such as granite, diorite of different age and size". The northern regions of the Hindu Kush witness Himalayan winter and have glaciers, while its southeastern end witness the fringe of Indian subcontinent summer monsoons.[50]

The Hindu Kush range remains geologically active and is still rising[55] - it is prone to earthquakes.[56][57] The Hindu Kush system stretches about 966 kilometres (600 mi) laterally,[58] and its median north-south measurement is about 240 kilometres (150 mi).The mountains are orographically described in several parts.[50] Peaks in the western Hindu Kush rise to over 5,100 m (16,700 ft) and stretches between Darra-ye Sekari and the Shibar Pass in the west and the Khawak Pass in the east.[50] The central Hindu Kush peaks rise to over 6,800 m (22,300 ft), and this section has numerous spurs between the Khawak Pass in the east and the Durāh Pass in the west.

The eastern Hindu Kush, also known as the "High Hindu Kush", is mostly located in northern Pakistan and the Nuristan and Badakhshan provinces of Afghanistanas with peaks over 7,000 m (23,000 ft). This section extends from the Durāh Pass to the Baroghil Pass at the border between northeastern Afghanistan and north Pakistan. The Chitral District of Pakistan is home to Tirich Mir, Noshaq, and Istoro Nal - the highest peaks in the Hindu Kush. The ridges between Khawak Pass and Badakshan is over 5,800 m (19,000 ft) and is called the Kaja Mohammed range.[50]

Peaks

Many peaks of the range are between 4,400 and 5,200 m (14,500 and 17,000 ft), and some much higher, with an average peak height of 4,500 metres (14,800 feet).[58] The mountains of the Hindu Kush range diminish in height as they stretch westward. Near Kabul, in the west, they attain heights of 3,500 to 4,000 metres (11,500 to 13,100 ft); in the east they extend from 4,500 to 6,000 metres (14,800 to 19,700 ft).

| Name | Height | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Tirich Mir | 7,708 metres (25,289 ft) | Pakistan |

| Noshak | 7,492 metres (24,580 ft) | Afghanistan, Pakistan |

| Istor-o-Nal | 7,403 metres (24,288 ft) | Pakistan |

| Saraghrar | 7,338 metres (24,075 ft) | Pakistan |

| Udren Zom | 7,140 metres (23,430 ft) | Pakistan |

| Lunkho e Dosare | 6,901 metres (22,641 ft) | Afghanistan, Pakistan |

| Kuh-e Bandaka | 6,843 metres (22,451 ft) | Afghanistan |

| Koh-e Keshni Khan | 6,743 metres (22,123 ft) | Afghanistan |

| Sakar Sar | 6,272 metres (20,577 ft) | Afghanistan, Pakistan |

| Kohe Mondi | 6,234 metres (20,453 ft) | Afghanistan |

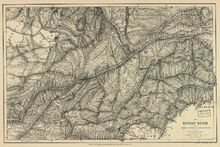

Passes

Numerous high passes ("kotal") transect the mountains, forming a strategically important network for the transit of caravans. The most important mountain pass in Afghanistan is the Salang Pass (Kotal-e Salang) (3,878 m or 12,723 ft) north of Kabul, which links southern Afghanistan to northern Afghanistan. The Salang Tunnel at 3,363 m (11,033 ft) and the extensive network of galleries on the approach roads were constructed with Soviet financial and technological assistance and involved drilling 2.7 km (1.7 mi) through the heart of the Hindu Kush, and has been an active area of armed conflict with various parties trying to control it.[59] The range has several other passes in Afghanistan, the lowest of which is the southern Shibar pass (2,700 m or 9,000 ft) where the Hindu Kush range terminates.[25]

Other mountain passes are at altitudes of about 3,700 m (12,000 ft) or higher,[25] including the Broghil Pass at 12460 feet in Pakistan,[60] and the Dorah Pass between Paksitan and Afghanistan at 14,000 feet. Other high passes in Pakistan include the Lowari Pass at 10,200 feet,[61] the Gomal Pass.

History

The high altitudes of the mountains have historical significance in South and Central Asia. The Hindu Kush range was a major centre of Buddhism with sites such as the Bamiyan Buddhas.[62] It has also been the passageway during the invasions of the Indian subcontinent,[23][24] a region where the Taliban and Al Qaeda grew,[26][63] and to modern era warfare in Afghanistan.[25] In ancient mines producing lapis lazuli are found in Kowkcheh Valley, while gem-grade emeralds are found north of Kabul in the valley of the Panjsher River and some of its tributaries. According to Walter Schumann, the West Hindu Kush mountains have been the source of finest Lapis lazuli for thousands of years.[64]

Buddhism was widespread in the ancient Hindu Kush region. Ancient artwork of Buddhism include the giant rock carved statues called the Bamiyan Buddha, in the southern and western end of the Hindu Kush.[18] These statues were blown up by the Taliban Islamists.[65] The southeastern valleys of Hindu Kush connecting towards the Indus Valley region were a major centre that hosted monasteries, religious scholars from distant lands, trade networks and merchants of ancient Indian subcontinent.[21]

One of the early Buddhist schools, the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda, was prominent in the area of Bamiyan. The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang visited a Lokottaravāda monastery in the 7th century CE, at Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Birchbark and palm leaf manuscripts of texts in this monastery's collection, including Mahāyāna sūtras, have been discovered in the caves of Hindu Kush,[66] and these are now a part of the Schøyen Collection. Some manuscripts are in the Gāndhārī language and Kharoṣṭhī script, while others are in Sanskrit and written in forms of the Gupta script.[67][68]

According to Alfred Foucher, the Hindu Kush and nearby regions gradually converted to Buddhism by the 1st century CE, and this region was the base from where Buddhism crossed the Hindu Kush expanding into the Oxus valley region of Central Asia.[69] Buddhism vanished and locals later became Muslims. Richard Bulliet also proposes that the area north of Hindu Kush was centre of a new sect which had spread as far as Kurdistan, remaining in existence until the Abbasid times.[70][71] The area came under control of the Hindu Shahi dynasty of Kabul.[72] The Islamic conquest under Sabuktigin who conquered Jayapala's dominion west of Peshawar.[73]

Ancient

The significance of the Hindu Kush mountains ranges has been recorded since the time of Darius I of Persia. Alexander the Great entered the Indian subcontinent through the Hindu Kush as his army moved past the Afghan Valleys in the spring of 329 BCE.[74] He moved towards the Indus Valley river region in Indian subcontinent in 327 BCE, his armies building several towns in this region over the intervening two years.[75]

After Alexander the Great's death in 323 BCE, the region became part of the Seleucid Empire, according to the ancient history of Strabo written in 1st century BCE, before it became a part of the Indian Maurya Empire around 305 BCE.[76] The region became a part of the Kushan Empire around the start of the common era.[77]

Medieval era

The lands north of the Hindu Kush, in the Hephthalite dominion, Buddhism was the predominant religion by mid 1st millennium CE.[78] These Buddhists were religiously tolerant and they co-existed with followers of Zoroastrianism, Manichaseism, and Nestorian Christianity.[78][79] This Central Asia region along the Hindu Kush was taken over by Western Turks and Arabs by the eighth century, facing wars with mostly Iranians.[78] One major exception was the period in the mid to late seventh century, when the Tang dynasty from China destroyed the Northern Turks and extended its rule all the way to the Oxus River valley and regions of Central Asia bordering all along the Hindu Kush.[80]

The subcontinent and valleys of the Hindu Kush remained unconquered by the Islamic armies until the 9th century, even though they had conquered the southern regions of Indus River valley such as Sind.[81] Kabul fell to the army of Al-Ma'mun, the seventh Abbasid caliph, in 808 and the local king agreed to accept Islam and pay annual tributes to the caliph.[81] However, states André Wink, inscriptional evidence suggests that the Kabul area near Hindu Kush had an early presence of Islam.[82]

The range came under control of the Hindu Shahi dynasty of Kabul[72] but was conquered by Sabuktigin who took all of Jayapala's dominion west of Peshawar.[73]

Mahmud of Ghazni came to power in 998 CE, in Ghazna, Afghanistan, south of Kabul and the Hindu Kush range.[83] He began a military campaign that rapidly brought both sides of the Hindu Kush range under his rule. From his mountainous Afghani base, he systematically raided and plundered kingdoms in north India from east of the Indus river to west of Yamuna river seventeen times between 997 and 1030.[84] Mahmud of Ghazni raided the treasuries of kingdoms, sacked cities, and destroyed Hindu temples, with each campaign starting every spring, but he and his army returned to Ghazni and the Hindu Kush base before monsoons arrived in the northwestern part of the subcontinent.[83][84] He retracted each time, only extending Islamic rule into western Punjab.[85][86]

In 1017, the Iranian Islamic historian Al-Biruni was deported after a war that Mahmud of Ghazni won,[87] to the northwest Indian subcontinent under Mahmud's rule. Al Biruni stayed in the region for about fifteen years, learnt Sanskrit, and translated many Indian texts, and wrote about Indian society, culture, sciences, and religion in Persian and Arabic. He stayed for some time in the Hindu Kush region, particularly near Kabul. In 1019, he recorded and described a solar eclipse in what is the modern era Laghman Province of Afghanistan through which Hindu Kush pass.[87] Al Biruni also wrote about early history of the Hindu Kush region and Kabul kings, who ruled the region long before he arrived, but this history is inconsistent with other records available from that era.[82] Al Biruni was supported by Sultan Mahmud.[87] Al Biruni found it difficult to get access to Indian literature locally in the Hindu Kush area, and to explain this he wrote, "Mahmud utterly ruined the prosperity of the country, and performed wonderful exploits by which the Hindus became the atoms scattered in all directions, and like a tale of old in the mouth of the people. (...) This is the reason, too, why Hindu sciences have retired far from those parts of the country conquered by us, and have fled to places which our hand cannot yet reach, to Kashmir, Benares and other places".[88]

In late 12th century, the historically influential Ghurid empire led by Mu'izz al-Din ruled the Hindu Kush region.[89] He was influential in seeding the Delhi Sultanate, shifting the base of his Sultanate from south of the Hindu Kush range and Ghazni towards the Yamuna River and Delhi. He thus helped bring the Islamic rule to the northern plains of Indian subcontinent.[90]

The Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta arrived in the Delhi Sultanate by passing through the Hindu Kush.[22] The mountain passes of the Hindu Kush range were used by Timur and his army and they crossed to launch the 1398 invasion of northern Indian subcontinent.[91] Timur, also known as Temur or Tamerlane in Western scholarly literature, marched with his army to Delhi, plundering and killing all the way.[92][93][94] He arrived in the capital Delhi where his army looted and killed its residents.[95] Then he carried the wealth and the captured slaves, returning to his capital through the Hindu Kush.[92][94][96]

Babur, the founder of Mughal Empire, was a patrilineal descendant of Timur with roots in Central Asia.[97] He first established himself and his army in Kabul and the Hindu Kush region. In 1526, he made his move into north India, won the Battle of Panipat, ending the last Delhi Sultanate dynasty, and starting the era of the Mughals.[98]

Slavery

Slavery, as with all major ancient and medieval societies, has been a part of Central Asia and South Asia history. The Hindu Kush mountain passes connected the slave markets of Central Asia with slaves seized in South Asia.[99][100][101] The seizure and transportation of slaves from the Indian subcontinent became intense in and after the 8th century CE, with evidence suggesting that the slave transport involved "hundreds of thousands" of slaves from India in different periods of Islamic rule era.[100] According to John Coatsworth and others, the slave trading operations during the pre-Akbar Mughal and Delhi Sultanate era "sent thousands of Hindus every year north to Central Asia to pay for horses and other goods".[102][103] However, the interaction between Central Asia and South Asia through the Hindu Kush was not limited to slavery, it included trading in food, goods, horses and weapons.[104]

The practice of raiding tribes, hunting, and kidnapping people for slave trading continued through the 19th century, at an extensive scale, around the Hindu Kush. According to a British Anti-Slavery Society report of 1874, the governor of Faizabad, Mir Ghulam Bey, kept 8,000 horses and cavalry men who routinely captured non-Muslim infidels (kafir) as well as Shia Muslims as slaves. Others alleged to be involved in slave trade were feudal lords such as Ameer Sheer Ali. The isolated communities in the Hindu Kush were one of the targets of these slave hunting expeditions.[105]

Modern era

In early 19th century, the Sikh Empire expanded under Ranjit Singh in the northwest as far as the Hindu Kush range.[106] The last polytheistic stronghold remained in the region until 1896, called "Kafiristan" whose people practised a form of polytheism (or were possibly nondenominational Muslims) until invasion and conversion at the hands of Afghans under Amir Abdur Rahman Khan.[20]

The Hindu Kush served as a geographical barrier to the British empire, leading to paucity of information and scarce direct interaction between the British colonial officials and Central Asian peoples. The British had to rely on tribal chiefs, Sadozai and Barakzai noblemen for information, and they generally downplayed the reports of slavery and other violence for geo-political strategic considerations.[107]

In the colonial era, the Hindu Kush were considered, informally, the dividing line between Russian and British areas of influence in Afghanistan. During the Cold War the Hindu Kush range became a strategic theatre, especially during the 1980s when Soviet forces and their Afghani allies fought the Mujahideen with support from the United States channelled through Pakistan.[108][109][110] After the Soviet withdrawal and the end of the Cold War, many Mujahideen morphed into Taliban and Al Qaeda forces imposing a strict interpretation of Islamic law (Sharia), with Kabul, these mountains, and other parts of Afghanistan as their base.[111][112] Other Mujahideen joined the Northern Alliance to oppose the Taliban rule.[112]

After the 11 September 2001 terror attacks in New York City and Washington D.C., the American and ISAF campaign against Al Qaeda and their Taliban allies made the Hindu Kush once again a militarised conflict zone.[112][113][114]

Ethnography

The mountains remained a stronghold of polytheistic faiths until the 19th century.[20] Pre-Islamic populations of the Hindu Kush included Shins, Yeshkun,[115] Chiliss, Neemchas[116] Koli,[117] Palus,[117] Gaware,[118] Yeshkuns,[119] and Krammins.[119]

See also

- Mount Imeon

- Paropamisus Mountains

- Himalayas

- A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush

- Geography of Afghanistan

- Geography of Pakistan

- Hindustan

- List of highest mountains (a list of mountains above 7,200m)

- List of mountain ranges

- 2002 Hindu Kush earthquakes

- 2005 Hindu Kush earthquake

References

Citations

- Hindu Kush, Encyclopedia Iranica

- The National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic Society. 1958.

Such bitter journeys gave the range its name, Hindu Kush — "Killer of Hindus."

- Metha, Arun (2004). History of medieval India. ABD Publishers.

of the Shahis from Kabul to behind the Hindu Kush mountains (Hindu Kush is literally "killer of Hindus"

- R. W. McColl (2014). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. pp. 413–414. ISBN 978-0-8160-7229-3.

- Allan, Nigel (2001). "Defining Place and People in Afghanistan". Post-Soviet Geography and Economics. 8. 42 (8): 546. doi:10.1080/10889388.2001.10641186.

- Runion, Meredith L. (24 April 2017). The History of Afghanistan, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-778-1.

The literal translation of the name “Hindu Kush” is a true reflection of its forbidding topography, as this difficult and jagged section of Afghanistan translates to “Killer of Hindus.”

- Weston, Christine (1962). Afghanistan. Scribner.

To the north and northeast, magnificent and frightening, stretched the mountains of the Hindu Kush, or Hindu Killers, a name derived from the fact that in ancient times slaves brought from India perished here like flies from exposure and cold.

- Knox, Barbara (2004). Afghanistan. Capstone. ISBN 978-0-7368-2448-4.

Hindu Kush means "killer of Hindus." Many people have died trying to cross these mountains.

- Mike Searle (2013). Colliding Continents: A geological exploration of the Himalaya, Karakoram, and Tibet. Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-19-165248-6., Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan".

- George C. Kohn (2006). Dictionary of Wars. Infobase Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4381-2916-7.

- "Hindu Kush Himalayan Region". ICIMOD. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Elalem, Shada; Pal, Indrani (2015). "Mapping the vulnerability hotspots over Hindu-Kush Himalaya region to flooding disasters". Weather and Climate Extremes. 8: 46–58. doi:10.1016/j.wace.2014.12.001.

- "Development of an ASSESSment system to evaluate the ecological status of rivers in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan region" (PDF). Assess-HKH.at. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Karakoram Range: MOUNTAINS, ASIA, Encyclopedia Britannica

- Stefan Heuberger (2004). The Karakoram-Kohistan Suture Zone in NW Pakistan – Hindu Kush Mountain Range. vdf Hochschulverlag AG. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-3-7281-2965-9.

- Spīn Ghar Range, MOUNTAINS, PAKISTAN-AFGHANISTAN, Encyclopedia Britannica

- Jonathan M. Bloom; Sheila S. Blair (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 389–390. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- Deborah Klimburg-Salter (1989), The Kingdom of Bamiyan: Buddhist art and culture of the Hindu Kush, Naples – Rome: Istituto Universitario Orientale & Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, ISBN 978-0877737650 (Reprinted by Shambala)

- Claudio Margottini (2013). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. Springer. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-3-642-30051-6.

- Augusto S. Cacopardo (15 February 2017). Pagan Christmas: Winter Feasts of the Kalasha of the Hindu Kush. Gingko Library. ISBN 978-1-90-994285-1.

- Jason Neelis (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. BRILL Academic. pp. 114–115, 144, 160–163, 170–176, 249–250. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5.

- Ibn Battuta; Samuel Lee (Translator) (2010). The Travels of Ibn Battuta: In the Near East, Asia and Africa. Cosimo (Reprint). pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1-61640-262-4.; Columbia University Archive

- Konrad H. Kinzl (2010). A Companion to the Classical Greek World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 577. ISBN 978-1-4443-3412-8.

- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th–13th centuries. BRILL Academic. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-391-04174-5.

- Frank Clements (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8.

- Michael Ryan (2013). Decoding Al-Qaeda's Strategy: The Deep Battle Against America. Columbia University Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-231-16384-2.

- Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19841-3. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Fosco Maraini et al., Hindu Kush, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Boyle, J.A. (1949). A Practical Dictionary of the Persian Language. Luzac & Co. p. 129.

- Francis Joseph Steingass (1992). A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary. Asian Educational Services. pp. 1030–1031 (kush means "killer, kills, slays, murders, oppresses"), p. 455 (khirs–kush means "bear killer"), p. 734 (shutur–kush means "camel butcher"), p. 1213 (mardum–kush means "man slaughter"). ISBN 978-81-206-0670-8.

- R. W. McColl (2014). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. pp. 413–414. ISBN 978-0-8160-7229-3.

- Amy Romano (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-8239-3863-6.

- [a] Michael Franzak (2010). A Nightmare's Prayer: A Marine Harrier Pilot's War in Afghanistan. Simon and Schuster. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-4391-9499-7.;

[b] Ehsan Yarshater (2003). Encyclopædia Iranica. The Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-933273-76-4.

[c] James Wynbrandt (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. Infobase Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8160-6184-6.;

[d] Encyclopedia Americana. 14. 1993. p. 206.;

[e] André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th–11th Centuries. BRILL Academic. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8., Quote: "(..) the Muslim Arabs also applied the name 'Khurasan' to all the Muslim provinces to the east of the Great Desert and up to the Hindu-Kush ('Hindu killer') mountains, the Chinese desert and the Pamir mountains". - Ewans, Sir Martin; Ewans, Martin; Weber, Patrick; Carr, Robyn (14 November 2002). Afghanistan - A New History. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-136-80339-0.

- The World Book Encyclopedia. 9 (1994 ed.). World Book Inc. 1990. p. 235.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. University of California Press. pp. 171–178. ISBN 978-0-520-24385-9.

- Alexander von Humboldt (17 July 2014). Stephen T. Jackson, Laura Dassow Walls (ed.). Views of Nature. University of Chicago Press. p. 68. ISBN 9780226923192.

- "HINDU KUSH – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Ervin Grötzbach (2012 Edition, Original: 2003), Hindu Kush, Encyclopaedia Iranica

- Henry Yule; A. C. Burnell (13 June 2013). Kate Teltscher (ed.). Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India. Oxford University Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780199601134.

- Julyan, Robert (1984). Mountain Names. Mountaineers. ISBN 978-0-89886-091-7.

- Allan, Nigel (2001). "Defining Place and People in Afghanistan". Post-Soviet Geography and Economics. 8. 42 (8): 545–560. doi:10.1080/10889388.2001.10641186.

- R. W. McColl (2014). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. pp. 413–414. ISBN 978-0-8160-7229-3.

- 1890,1896 Encyclopedia Britannica s.v. "Afghanistan", Vol I p.228.;

1893, 1899 Johnson's Universal Encyclopedia Vol I p.61.;

1885 Imperial Gazetteer of India, V. I p. 30.;

1850 A Gazetteer of the World Vol I p. 62. - Karl Jettmar; Schuyler Jones (1986). The Religions of the Hindukush: The religion of the Kafirs. Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-163-9.

- Winiger, M.; Gumpert, M.; Yamout, H. (2005). "Karakorum-Hindukush-western Himalaya: assessing high-altitude water resources". Hydrological Processes. Wiley-Blackwell. 19 (12): 2329–2338. Bibcode:2005HyPr...19.2329W. doi:10.1002/hyp.5887.

- Ahmad, Masood; Wasiq, Mahwash (1 January 2004). Water Resource Development in Northern Afganistan and Its Implications for Amu Darya Basin. World Bank Publications. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8213-5890-0.

- History of Environmental Change in the Sistan Basin, UNEP, United Nations, pages 5, 12-14

- Ahmad, Masood; Wasiq, Mahwash (1 January 2004). Water Resource Development in Northern Afganistan and Its Implications for Amu Darya Basin. World Bank Publications. ISBN 978-0-8213-5890-0.

- Ehsan Yarshater (2003). Encyclopædia Iranica. The Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-933273-76-4.

- Nicks, Oran W., ed. (1970). This Island Earth. NASA. p. 66.

- Robert Wynn Jones (2011). Applications of Palaeontology: Techniques and Case Studies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 267–271. ISBN 978-1-139-49920-0.

- Hinsbergen, D. J. J. van; Lippert, P. C.; Dupont-Nivet, G.; McQuarrie, N.; Doubrovine; et al. (2012). "Greater India Basin hypothesis and a two-stage Cenozoic collision between India and Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (20): 7659–7664, for geologic Indian subcontinent see Figure 1. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.7659V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1117262109. PMC 3356651. PMID 22547792.

- S. Mukherjee; R. Carosi; P.A. van der Beek; et al. (2015). Tectonics of the Himalaya. Geological Society of London. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-1-86239-703-3.

- Martin Beniston (2002). Mountain Environments in Changing Climates. Routledge. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-134-85236-9.

- Frank Clements (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8.

- Afghanistan Pakistan Earthquake National Geographic;

Afghanistan earthquake BBC News; See also October 2015 Hindu Kush earthquake and 2016 Afghanistan earthquake. - Scott-Macnab, David (1994). On the roof of the world. London: Reader's Digest Assiciation Ldt. p. 22.

- John Laffin (1997). The World in Conflict: War Annual 8 : Contemporary Warfare Described and Analysed. Brassey's. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-85753-216-6.

- Burrard, Sir Sidney Gerald (1908). A Sketch of the Geography and Geology of the Himalaya Mountains and Tibet. Superintendent government printing, India. p. 102.

- Authority, West Pakistan Water and Power Development (1971). WAPDA Annual Report. The Authority.

- Claudio Margottini (2013). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. Springer. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-3-642-30051-6.

- Magnus, Ralph H. (1998). "Afghanistan in 1997: The War Moves North". Asian Survey. University of California Press. 38 (2): 109–115. doi:10.2307/2645667. JSTOR 2645667.

- Walter Schumann (2009). Gemstones of the World. Sterling. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4027-6829-3.

- Jan Goldman (2014). The War on Terror Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 360–362. ISBN 978-1-61069-511-4.

- ASOKA MUKHANAGAVINAYAPARICCHEDA, The Schoyen Collection, Quote: "Provenance: 1. Buddhist monastery of Mahasanghika, Bamiyan, Afghanistan (−7th c.); 2. Cave in Hindu Kush, Bamiyan."

- "Schøyen Collection: Buddhism". Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- "Afghan archaeologists find Buddhist site as war rages". Sayed Salahuddin. News Daily. 17 August 2010. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Jason Neelis (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. BRILL Academic. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5.

- Sheila Canby (1993). "Depictions of Buddha Sakyamuni in the Jami al-Tavarikh and the Majma al-Tavarikh". Muqarnas. 10: 299–310. doi:10.2307/1523195. JSTOR 1523195.

- Michael Jerryson (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-19-936239-4.

- The History and Culture of the Indian People: The struggle for empire.-2d ed, Page 3

- Keay, John (12 April 2011). India: A History. ISBN 9780802195500.

- Peter Marsden (1998). The Taliban: War, Religion and the New Order in Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-85649-522-6.

- Peter Marsden (1998). The Taliban: War, Religion and the New Order in Afghanistan. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-85649-522-6.

- Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul – The Name". American International School of Kabul. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. 2. BRILL. p. 159. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th–11th Centuries. BRILL Academic. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- M. A. Shaban (1979). The 'Abbāsid Revolution. Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-521-29534-5.

- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th–11th Centuries. BRILL Academic. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th–11th Centuries. BRILL Academic. pp. 9–10, 123. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th–11th Centuries. BRILL Academic. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4, 6–7. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- T. A. Heathcote, The Military in British India: The Development of British Forces in South Asia:1600–1947, (Manchester University Press, 1995), pp 5–7

- Barnett, Lionel (1999), Antiquities of India: An Account of the History and Culture of Ancient Hindustan, p. 1, at Google Books, Atlantic pp. 73–79

- Al-Biruni Bobojan Gafurov (June 1974), The Courier Journal, UNESCO, page 13

- William J. Duiker; Jackson J. Spielvogel (2013). The Essential World History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-133-60772-4.

- K.A. Nizami (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. p. 186. ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–15, 24–27. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- Francis Robinson (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-521-66993-1.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 311–319. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- Beatrice F. Manz (2000). "Tīmūr Lang". In P. J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C. E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W. P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. 10 (2 ed.). Brill.

- Annemarie Schimmel (1980). Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. BRILL. pp. 36–44. ISBN 978-90-04-06117-0.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Paddy Docherty (2007). The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion. London: Union Square. pp. 160–162. ISBN 978-1-4027-5696-2.

- Gerhard Bowering; Patricia Crone; Wadad Kadi; et al. (2012). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0691134840.

- Scott Cameron Levi; Muzaffar Alam (2007). India and Central Asia: Commerce and Culture, 1500–1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-19-568647-0.

- Scott C. Levi (2002), Hindus beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Cambridge University Press, Volume 12, Number 3 (Nov. 2002), pages 277–288

- Christoph Witzenrath (2016). Eurasian Slavery, Ransom and Abolition in World History, 1200–1860. Routledge. pp. 10–11 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-317-14002-3.

- Scott Cameron Levi; Muzaffar Alam (2007). India and Central Asia: Commerce and Culture, 1500–1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 11–12, 43–49, 86 note 7, 87 note 18. ISBN 978-0-19-568647-0.

- John Coatsworth; Juan Cole; Michael P. Hanagan; et al. (2015). Global Connections: Volume 2, Since 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-316-29790-2.

- According to Clarence-Smith, the practice was curtailed but continued during Akbar's era, and returned after Akbar's death; W. G. Clarence-Smith (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-19-522151-0.

- Scott Cameron Levi; Muzaffar Alam (2007). India and Central Asia: Commerce and Culture, 1500–1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–10, 53, 126, 160–161. ISBN 978-0-19-568647-0.

- Junius P. Rodriguez (2015). Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. Routledge. pp. 666–667. ISBN 978-1-317-47180-6.

- J. S. Grewal (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0.

- Jonathan L. Lee (1996). The "Ancient Supremacy": Bukhara, Afghanistan and the Battle for Balkh, 1731–1901. BRILL Academic. pp. 74 with footnote. ISBN 978-90-04-10399-3.

- Mohammed Kakar (1995). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. University of California Press. pp. 130–133. ISBN 978-0-520-91914-3.

- Scott Gates; Kaushik Roy (2016). Unconventional Warfare in South Asia: Shadow Warriors and Counterinsurgency. Routledge. pp. 142–144. ISBN 978-1-317-00541-4.

- Mark Silinsky (2014). The Taliban: Afghanistan's Most Lethal Insurgents. ABC-CLIO. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-313-39898-8.

- Mark Silinsky (2014). The Taliban: Afghanistan's Most Lethal Insurgents. ABC-CLIO. pp. 8, 37–39, 81–82. ISBN 978-0-313-39898-8.

- Nicola Barber (2015). Changing World: Afghanistan. Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-62513-318-2.

- A Short March to the Hindu Kush, Alpinist 18.

- "Alexander in the Hindu Kush". Livius. Articles on Ancient History. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- Biddulph, p.38

- Biddulph, p.7

- Biddulph, p.9

- Biddulph, p.11

- Biddulph, p.12

Bibliography

- Biddulph, John (2001) [1880]. Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel. ISBN 9789693505825. OCLC 223434311. Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh at Google Books (facsimile of the original edition).

Further reading

- Drew, Frederic (1877). The Northern Barrier of India: A Popular Account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations. Frederic Drew. 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu, 1971

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1929). Ibn Battūta: Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354. Translated and selected by H. A. R. Gibb. Reprint: Asian Educational Services, New Delhi and Madras, 1992

- Gordon, T. E. (1876). The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the High Plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus Sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint: Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company. Tapei, 1971

- Leitner, Gottlieb Wilhelm (1890). Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893: Being An Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial) Yasin, Chitral, Hunza, Nagyr and other parts of the Hindukush, as also a supplement to the second edition of The Hunza and Nagyr Handbook. And An Epitome of Part III of the author's 'The Languages and Races of Dardistan'. Reprint, 1978. Manjusri Publishing House, New Delhi. ISBN 81-206-1217-5

- Newby, Eric. (1958). A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. Secker, London. Reprint: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-0-86442-604-8

- Yule, Henry and Burnell, A. C. (1886). Hobson-Jobson: The Anglo-Indian Dictionary. 1996 reprint by Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-363-X

- A Country Study: Afghanistan, Library of Congress

- Ervin Grötzbach, Hindu Kush at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed., Vol. 21, pp. 54–55, 65, 1987

- An Advanced History of India, by R. C. Majumdar, H. C. Raychaudhuri, K.Datta, 2nd Ed., MacMillan and Co., London, pp. 336–37, 1965

- The Cambridge History of India, Vol. IV: The Mughul Period, by W. Haig & R. Burn, S. Chand & Co., New Delhi, pp. 98–99, 1963

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hindu Kush |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hindu Kush. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hindu Kush. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hindu Kush. |

_(14592652167).jpg)