Tibesti Mountains

The Tibesti Mountains are a mountain range in the central Sahara, primarily located in the extreme north of Chad, with a small extension into southern Libya. The highest peak in the range, Emi Koussi, lies to the south at a height of 3,445 metres (11,302 ft) and is the highest point in both Chad and the Sahara. Bikku Bitti, the highest peak in Libya, is located in the north of the range. The central third of the Tibesti is of volcanic origin and consists of five volcanoes topped by large craters: Emi Koussi, Tarso Toon, Tarso Voon, Tarso Yega and Toussidé. Major lava flows have formed vast plateaus that overlie Paleozoic sandstone. The volcanic activity was the result of a continental hotspot that arose during the Oligocene and continued in some places until the Holocene, creating fumaroles, hot springs, mud pools and deposits of natron and sulfur. Erosion has shaped volcanic spires and carved an extensive network of canyons through which run rivers subject to highly irregular flows that are rapidly lost to the desert sands.

| Tibesti | |

|---|---|

The Tibesti, including Emi Koussi summit, seen from the International Space Station | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Emi Koussi |

| Elevation | 3,445 m (11,302 ft) |

| Coordinates | 18°33′6″N 19°47′36″E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 380 km (240 mi) |

| Width | 350 km (220 mi) |

| Area | 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| |

| Countries | Chad and Libya |

| Range coordinates | 20°46′59″N 18°03′00″E |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Oligocene |

| Type of rock | Basalt, Dacite, Ignimbrite, Trachyte and Sandstone |

Tibesti, which means "place where the mountain people live," is the domain of the Toubou people. The Toubou live mainly along the wadis, on rare oases where palm trees and limited grains grow. They harness the water that collects in gueltas, the supply of which is highly variable from year-to-year and decade-to-decade. The plateaus are used to graze livestock in the winter and harvest grain in the summer. Temperatures are high, although the altitude ensures that the range is cooler than the surrounding desert. The Toubou, who first appeared in the range in the 5th century BC, adapted to these conditions and turned the range into a large natural fortress. They arrived in several waves, taking refuge in times of conflict and dispersing in times of prosperity, although not without intense internal hostility at times.

The Toubou came into contact with the Carthaginians, Berbers, Tuaregs, Ottomans and the Arabs, as well as the French colonists who first entered the range in 1914 and took control of the area in 1929. The independent spirit of the Toubou and the geopolitical situation in the region has complicated the exploration of the range as well as the ascent of its peaks. Tensions continued after Chad and Libya gained independence in the mid-20th century, with hostage-taking and armed struggles occurring amid border disputes over the allocation of natural resources. The geopolitical situation and the lack of infrastructure has hampered the development of tourism.

The Saharomontane flora and fauna, which include the rhim gazelle and Barbary sheep, have adapted to the mountains, yet the climate has not always been as harsh. Greater biodiversity existed in the past, as evidenced by scenes portrayed in rock and parietal art found throughout the range, which date back several millennia, even before the arrival of the Toubou. The isolation of the Tibesti has sparked the cultural imagination in both art and literature.

Toponymy

The Tibesti Mountains are named for the Toubou people, also written Tibu or Tubu, that inhabit the area. In the Kanuri language, tu means "rock" or "mountain" and bu means "a person" or "dweller," and thus Toubou roughly translates to "people of the mountains"[lower-alpha 1] and Tibesti to "place where the mountain people live."[1][2]

Most of the mountain names are derived from Arabic as well as the Tedaga and Dazaga languages. The term ehi refers to peaks and rocky hills, emi to larger mountains, era to craters and tarso to high plateaus or gently sloping mountains. For example, the Ehi Mousgou is a 2,849-metre (9,347 ft) stratovolcano near Tarso Voon; likewise, Era Kohor is a crater on top of Emi Koussi.[3][4][5] The name Toussidé means "that which killed the Tou," as in the Toubou, reflecting the danger of the still active volcano.[6][7] The name of Bardaï, the principal town in the range, means "cold" in Chadian Arabic, because of its low nocturnal temperatures. In the Tedaga language, the town is known as Goumodi, which means "red pass," signifying the color of the mountains at dusk.[8]

Geography

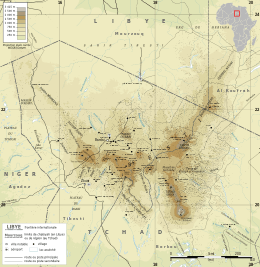

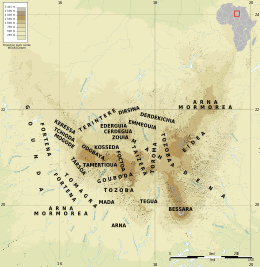

Location

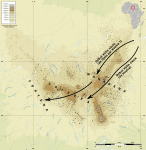

The mountains lie on the border between Chad and Libya, straddling the Chadian regions of Borkou and Tibesti and the Libyan districts of Murzuq and Kufra, around 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north of N'djamena and 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) south-southeast of Tripoli. The range is adjacent to Niger and located approximately halfway between the Mediterranean Sea and Lake Chad, just south of the Tropic of Cancer.[9] The East African Rift is 1,900 km (1,200 mi) to the east and the Cameroon line lies 1,800 km (1,100 mi) to the southwest.[3]

The range is 380 km (240 mi) in length, 350 km (220 mi) in width,[10] and spans 100,000 km2 (39,000 sq mi).[11][12] It draws a large triangle with sides of 400 km (250 mi)[9] and vertices facing south, northwest and northeast in the heart of the Sahara, making it the largest geologic area of the desert.[13] It is slightly larger than the Massif Central in France, with which it shares some geomorphological characteristics.[14]

Topography

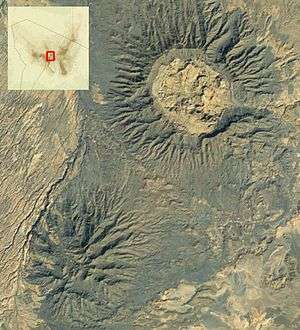

The highest peak in the Tibesti Mountains, as well as the highest point in Chad and the Sahara Desert, is the 3,445-metre (11,302 ft)[lower-alpha 2] Emi Koussi, located at the southern end of the range.[13] Other prominent peaks include Pic Toussidé[lower-alpha 3] at 3,296 m (10,814 ft) and the 3,012-metre (9,882 ft) Ehi Timi on its western side, the 2,972-metre (9,751 ft) Tarso Yega, the 2,925 m (9,596 ft) Tarso Tieroko, the 2,849-metre (9,347 ft) Ehi Mousgou, the 2,845-metre (9,334 ft) Tarso Voon, the 2,820-metre (9,250 ft) Ehi Sunni, and the 2,774-metre (9,101 ft) Ehi Yéy near the center of the range.[16] The 2,978-metre (9,770 ft) Mouskorbe[17] and the 2,812-metre (9,226 ft) Kegueur Terbi[18] are two peaks notable for their height in the northeastern part of the mountain range. The 2,267-metre (7,438 ft) Bikku Bitti, the highest point in Libya, is nearby, on the other side of the border. The average elevation of the Tibesti Mountains is about 2,000 metres (6,600 ft); sixty percent of its area exceeds 1,500 m (4,900 ft) in elevation.[13]

The range includes five shield volcanoes whose diameter can reach 80 km (50 mi), with broad bases and the steepest peaks topped with large craters: Emi Koussi; Tarso Toon, which rises 2,575 m (8,448 ft) above sea level; Tarso Voon; Tarso Yega; and Tarso Toussidé, which culminates in the peak of the same name.[7][12][16][19] Tarso Yega has the largest crater, with a diameter of 20 km (12 mi) and a depth of approximately 300 m (980 ft), while Tarso Voon has the deepest crater, with a depth of approximately 1,000 m (3,300 ft) and a diameter of 12 to 13 km (7.5 to 8.1 mi).[16][20] They are complemented by four large lava dome complexes, 1,300 to 2,000 m (4,300 to 6,600 ft) high and several km wide, all located in the central part of the mountain range: Tarso Tieroko; Ehi Yéy; Ehi Mousgou; and Tarso Abeki, which rises to 2,691 m (8,829 ft) above sea level.[16] These volcanic complexes are now considered inactive, but according to the Smithsonian Institution were active during the Holocene.[21] Tarso Toussidé is an active volcano that has spewed lava over the past two millennia. Gases escaping from fumaroles on Toussidé are visible when evaporation is low. The volcano's crater, Trou au Natron, is 8 km (5.0 mi) in diameter and 768 m (2,520 ft) deep.[6][7][16] On the northwest side of Tarso Voon is the Soborom geothermal field, which contains mud pools and fumaroles that vent sulfuric acid. Sulfur and iron have stained the soil bright colors.[7] Fumaroles are also present at the Yi Yerra hot springs on Emi Koussi.[7] Tarso Tôh was an active volcano in the early Holocene.[21] The volcanic area of the Tibesti Mountains is located entirely in Chad; it covers about a third of the total area of the Tibesti Mountains and is responsible for between 5,000 and 6,000 km3 (1,200 and 1,400 cu mi) of rock.[7][3][22]

- The five shield volcanoes of the Tibesti Mountains

- Satellite image of Emi Koussi

Satellite image of Tarso Toon (top right) and the Ehi Yéy (bottom left)

Satellite image of Tarso Toon (top right) and the Ehi Yéy (bottom left) Satellite image of Tarso Voon

Satellite image of Tarso Voon False color satellite image of Tarso Yega (top)

False color satellite image of Tarso Yega (top) Satellite image of Tarso Toussidé showing Pic Toussidé (the center of the dark spot) and Trou au Natron crater (top left)

Satellite image of Tarso Toussidé showing Pic Toussidé (the center of the dark spot) and Trou au Natron crater (top left)

The rest of the Tibesti Mountains consists of volcanic plateaus (tarsos in the Tedaga language), located between 1,200 and 2,800 m (3,900 and 9,200 ft) elevation, as well as lava fields and ejecta deposits.[12][16] The plateaus are larger and more numerous in the east: the 7,700 km2 (3,000 sq mi) Tarso Emi Chi, the 6,500 km2 (2,500 sq mi) Tarso Aozi, the 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi) Tarso Ahon to the north of Emi Koussi, and the 1,200 km2 (460 sq mi) Tarso Mohi. In the center is Tarso Ourari at about 700 km2 (270 sq mi). To the west, in the vicinity of Tarso Toussidé, are the small plateaus of Tarso Tôh and Tarso Tamertiou, at 490 km2 (190 sq mi) and 98 km2 (38 sq mi), respectively. The plateaus are strewn with volcanic spires and are separated by canyons that have been formed by the irregular flow of wadis.[7][23][14] The central part of the range is striated by a network of dry valleys with the north- and east- facing slopes silted by the prevailing winds. After the typically violent rains, these slopes form ephemeral streams and flora. The southwest slopes in the south and west of the mountain range have a gentle rise, while the northern slope of the range is a cliff overlooking the vast Libyan desert pavement known as the Sarir Tibesti.[24]

Hydrology

Five rivers in the northern half of the Tibesti Mountains flow to Libya and are part of the Mediterranean Basin, while the southern half belongs to the endorheic basin of Lake Chad.[13] However, none of the rivers travel long distances, as the water evaporates in the desert heat or seeps into the ground, although the latter may be carried great distances by subterranean aquifers.[13]

The wadis in the Tibesti are called enneris. The water originates from the storms that periodically rage over the mountains. Their flow is highly variable.[13] For example, the largest wadi, named Bardagué (or Enneri Zoumeri on its upstream portion) and located in the northern part of the range, recorded a flow of 425 m3/s (15,000 cu ft/s) in 1954, yet over the next nine years it experienced four years of total drought, four years of flow less than 5 m3/s (180 cu ft/s) and one year where three different flow rates were measured: 4, 9 and 32 m3/s (140, 320 and 1,130 cu ft/s).[13] This variability is partly due to the irregularity of the monsoon that can bring rainfall from the southwest up to 20 degrees north latitude, but in some years may retreat before it reaches this latitude.[13][25] Two other significant rivers cut into the mountains: the Enneri Yebige flows northward until its riverbed disappears on the Sarir Tibesti plateau, while Enneri Touaoul joins the south-flowing Enneri Ke to form Enneri Miski, which then disappears in the plains of Borkou. Their basins are separated by an 1,800-metre (5,900 ft) high watershed that runs from Tarso Tieroko in the west to Tarso Mohi in the east.[9][13] The Enneri Tijitinga is the longest wadi in the range, flowing some 400 km (250 mi) southward. It forms in the west of the range and peters out in the Bodélé Depression, as does Enneri Miski a little further to the east, along with other wadis such as the Enneri Korom and Enneri Aouei.[23] The Enneri Douanré also flows southward. The Enneri Torku and Enneri Ofoundoui lie to the north; the Enneri Uri, Enneri Binem and Enneri Modiounga are in the east; the Enneri Yeo, Enneri Mamar, Enneri Tao, Enneri Woudoui and Enneri Dooze are to the west.[26] Several rivers flow radially on the southern slopes of the Emi Koussi before seeping into the sands of Borkou and then reemerging at escarpments up to 400 km (250 mi) south of the summit, near the Ennedi Plateau.[23]

At the bottom of many canyons are gueltas, wetlands that accumulate water mainly during storms and which can last most of the year.[23] Above 2,000 m (6,600 ft), enneri beds sometimes contain sequential pools of water that remain largely unexplored.[23] The water is replenished several times a year during flooding, and salinity levels are low.[23] The Mare de Zoui is a small permanent body of water 600 m (2,000 ft) above sea level, located in the northern part of the mountains in the wadi of the Enneri Bardagué, 10 km (6.2 mi) north of Bardaï. Supplied by sources upstream of the wadi, in heavy rains it overflows and spills into small wetlands.[23]

The Yi Yerra hot springs is located on the southern flank of Emi Koussi,[27] at about 850 m (2,800 ft) elevation.[28] Water emerges from the springs at 37 °C (99 °F).[13] A dozen hot springs are also located at the Soborom geothermal field on the northwest side of Tarso Voon, where water emerges at temperatures ranging between 22 and 88 °C (72 and 190 °F).[13][29]

Geology

The Tibesti Mountains are a large area of tectonic uplift that, according to contemporary theory, resulted from a mantle plume[3][13][30] in the craton of the African lithosphere, which is about 130 to 140 km (81 to 87 mi) thick.[21][31] This tectonic uplift may have been accompanied by the opening, and subsequent closure via subduction, of a rift zone.[32][33] The heart of the Tibesti is composed of schist, basalt and diorite of the Ediacaran period, one of six exposures of Precambrian crystalline rock in North Africa. These are overlaid by sandstone of the Paleozoic era,[3][13][31] while the peaks consist of volcanic rock.[3]

The continental hotspot activity began as early as the Oligocene, although the basalt in the area dates primarily from the Miocene to the Lower Pleistocene[7][12][13][31] and, in places, to the Holocene.[21] Due to the comparatively slow movement of the African plate—between 0 and 20 mm (0 and 0.8 in) per year since the Oligocene[34]—there is no relationship between the age of the volcanoes and their dimensions, geographic distribution or alignment, similar to the Hawaiian–Emperor and Cook-Austral seamount chains.[21] This phenomenon is also seen in Martian volcanoes, particularly Elysium Mons.[35] The volcanic activity has created trap basalt formations that extend tens of kilometers and stack up to 300 m (1,000 ft) thick.[7] A system of regional faults, although partially obscured by the volcanic product, has two distinct orientations:[14] a NNE-SSW alignment that could be an extension of Cameroon line,[3][36][37][38] and a NNW-SSE alignment that could extend to the Great Rift Valley;[3] however, the relationship between these fault systems has not been conclusively demonstrated.[34] More recently in geologic time, the volcanic activity has deposited dacite[3] and ignimbrite,[3][39][40] as well as trachyte and trachyandesite.[27][41] This trend towards the production of more felsic, viscous lavas could be a sign of a waning mantle plume.[21]

The volcanic activity took place in several phases.[39] In the first phase, uplift and extension of the Precambrian basement occurred in the central area. The first structure to be formed was probably Tarso Abeki, followed by Tarso Tamertiou, Tarso Tieroko, Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon, and Ehi Yéy. The product of this early volcanic activity has been completely obscured by later eruptions.[39] In the second phase, the volcanic activity moved north and east, forming Tarso Ourari and the ignimbrite bases of the vast tarsos, as well as Emi Koussi to the southeast.[39] Thereafter, during the third phase, the outpouring of lava and ejecta deposits increased from Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon, Tarso Tieroko and Ehi Yéy; the collapse of these structures formed the first calderas. This phase also saw the formation of the Bounaï lava dome and Tarso Voon. To the east, the lava flows formed the large plateaus of Tarso Emi Chi, Tarso Ahon and Tarso Toon. Emi Koussi increased in height.[7][39] The fourth phase saw the formation of Tarso Toussidé and the lava flows of Tarso Tôh in the west, the collapse of the caldera on the summit of Tarso Voon and associated ejecta deposits in the center, and the decline in lava production in the east, with the exception of Emi Koussi, which continued to rise. The end of this phase coincided with the beginning of the Holocene.[39] The Yirrigué volcano emitted pyroclastic ignimbrite up to 50 km (31 mi) in all directions, filling in valleys.[7] In the fifth phase, volcanic activity became much more localized and lava production continued to wane. Calderas form on top of Tarso Toussidé and Emi Koussi, and the lava domes Ehi Sosso and Ehi Mousgou appeared.[39] Finally, in the sixth phase, Pic Toussidé formed on the western rim of several pre-Trou au Natron calderas, along with new lava flows, including Timi on the northern slope of Tarso Toussidé. With scarce time for erosion, these lava flows have a dark, youthful appearance. The Trou au Natron and Doon Kidimi craters have formed even more recently, with the former dissecting the earlier Toussidé calderas. Lava flows, minor pyroclastic deposits, and the appearance of small cinder cones, and the formation of the Era Kohor crater are the most recent volcanic activities on Emi Koussi.[7][39] Presently, there are reports of volcanic activity in various parts of the massif, including hot springs at the Soborom geothermal field and fumaroles on Tarso Voon, Yi Yerra near Emi Koussi and Pic Toussidé.[13][21] Deposits of sodium carbonate in the Trou au Natron and Era Kohor craters reflect recent events, as does the formation of volcanic centers on the floor of Trou au Natron.[7][21]

The study of fluvial terraces has revealed coarse sand and gravel alternating with terraces of silt, clay and fine sand. This alternation highlights repeated changes in the dominant fluvial or wind patterns in the valleys of Tibesti during the Quaternary Period. The phases of erosion and sendimentation are indicative of the climate alternating between dry and wet conditions, the latter of which fostered dense vegetation in the Tibesti that was likely far more diverse than that which exists today (with the exception of grasses).[42] Furthermore, the discovery of calcified charophyta (particularly of the family Characeae) and gastropod fossils in Trou au Natron indicates the presence of a lake at least 300 m (1,000 ft) deep during the Late Pleistocene.[43] These phenomena are associated with various changes in climate, most notably during the last glacial maximum, which increased precipitation and reduced evaporation due to lower temperatures.[44] In fact, the Tibesti supplied a considerable amount of water to the Paleolake Chad until the 5th millennium BC.[45]

Climate

The Tibesti climate is substantially less dry than that of the surrounding Sahara Desert. Rainfall events are more intense and more frequent, but they are also highly variable from year to year.[13] Indeed, the Tibesti can see seven to eight years pass between storms. In the south of the range, this variation is largely due to oscillations of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which steadily moves northward toward Northern Chad from November until August, accompanied by the humid monsoonal air. Normally, the ITCZ repels the Harmattan, a dry trade wind that blows south-west from the Sahara Desert, and brings rainfall to southern Tibesti.[25] However, sometimes the front retires early, before reaching the Tibesti, resulting one or more years of drought.[13] In the northern Tibesti, where the monsoon has little influence, storms are caused by Sahara-Sudanese weather systems.[13] For example, between 1957 and 1968, Bardaï saw an average of 12 mm (0.47 in) of precipitation annually, although some years were dry while others saw 60 mm (2.4 in) of rainfall.[13] In general, the range receives a little less than 20 mm (0.79 in) of rainfall per year.[25][23] However, at elevations above 2,000 m (6,600 ft), average precipitation exceeds 100 to 150 mm (3.9 to 5.9 in) per year. When the rainfall coincides with low temperatures, it can fall as snow.[13] This occurs, on average, once every seven years.[46]

The average maximum temperature is 30 °C (86 °F) at lower elevations and 20 °C (68 °F) in the highlands. The average minimum temperature is 12 °C (54 °F) in the valleys but only 9 °C (48 °F) on most plateaus, and it can drop to 0 °C (32 °F) on the highest peaks in winter.[47] Lows of −10 °C (14 °F) are not uncommon.[13] Bardaï, located in a wadi 1,020 m (3,350 ft) above sea level, experiences average temperatures ranging between 4.6 and 23.7 °C (40.3 and 74.7 °F) in winter, between 14.4 and 34 °C (57.9 and 93.2 °F) in spring, and between 19.4 and 36.7 °C (66.9 and 98.1 °F) in summer.[13] At Zouar, temperatures can rise to 44 °C (111 °F) in the summer and drop below 0 °C (32 °F) in the winter, and can fall to −19 °C (−2 °F) on the surrounding plateaus.[48]

| Climate data for the central Tibesti Mountains (21°15′N 17°45′W), approximately 1,200 m (3,900 ft) elevation | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.5) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

29.8 (85.7) |

34.2 (93.5) |

36.2 (97.2) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34 (94) |

33.1 (91.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

28.2 (82.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

12.8 (55.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21 (70) |

25.3 (77.6) |

27.3 (81.2) |

27 (81) |

26.5 (79.7) |

25.1 (77.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

15.1 (59.1) |

11.6 (52.8) |

19.9 (67.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.1 (46.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.9 (55.3) |

7.4 (45.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

11.8 (53.3) |

| Source: Global Species[47] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The Tibesti Mountains are part of the Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands ecoregion, which covers 82,000 km2 (31,700 sq mi).[49]

Flora

The flora in the Tibesti is Saharomontane, mixing Mediterranean, Sahara, Sahel and Afromontane vegetation. Biodiversity and endemism levels are much higher in the Tibesti than in the Aïr Mountains or the Ennedi Plateau,[50] although the vegetation's coverage is highly dependent on rainfall.[51] A number of oases lie along the courses of the enneris such as Enneri Yebige, which is virtually unexplored.[23] These oases, which are more numerous to the north and west of the range, have vegetation of the genera Acacia, Ficus (fig trees), Hyphaene and Tamarix.[23] Most gueltas are lined with macrophytes including Cyperus laevigatus, Equisetum ramosissimum, Juncus fontanesii and Scirpus holoschoenus.[23] Acacia nilotica grow near these water basins.[23] Myrtus nivellei and Nerium oleander grow between elevations of 1,500 and 2,300 m (4,900 and 7,500 ft) in the western part of the range, while Tamarix nilotica grow at similar elevations in its northern part.[51] Downstream, where the current of the enneris is slower and the riverbed is deeper, there are dense thickets of Tamarix aphylla and Salvadora persica (locally known as yii).

Around the edge of the Tibesti, where the canyons exit the range, are doum palms (Hyphaene thebaica, known locally as soboo).[23][52] The banks of Mare de Zoui are home to dense stands of reeds (Phragmites australis and Typha capensis), along with Scirpoides holoschoenus, Juncus maritimus, Juncus bufonius and Equisetum ramosissimum, while species of pond weed (Potamogeton) grow in the open water. Although the lake appears rich in phytoplankton, it has not been thoroughly studied.[23][51] To the south and southwest of the range, between 1,600 and 2,300 m (5,200 and 7,500 ft) elevation, the wadis support endemic Ficus salicifolia as well as woody species characteristic of the Sahel: Balanites aegyptiaca, Boscia salicifolia, Cordia sinensis, Ficus ingens, Ficus salicifolia, Ficus sycomorus, Flueggea virosa, Grewia tenax, Gymnosporia senegalensis, Rhus incana and also Senegalia laeta. Chrysopogon plumulosus is the most common Poaceae in the area. Other plants have more Mediterranean characteristics, such as Globularia alypum and Lavandula pubescens or the more tropical Abutilon fruticosum and Rhynchosia minima.[51][52]

Acacia laeta

Acacia laeta Acacia nilotica

Acacia nilotica Acacia seyal

Acacia seyal

_W_IMG_6939.jpg)

Saharomontane grasslands are found on the slopes, plateaus and the upper portions of the wadis at elevations between 1,800 and 2,700 m (5,900 and 8,900 ft). They are dominated by Stipagrostis obtusa and Aristida caerulescens, as well some Eragrostis papposa locally. In addition, shrubs represented by Anabasis articulata, Fagonia flamandii and Zilla spinosa dot this environment. On the sheltered upper slopes of Emi Koussi is the endemic grass Eragrostis kohorica, named after the volcano's crater.[51]

The vegetation above 2,600 m (8,500 ft) consists of dwarf shrubs, which are generally limited to 20 to 60 cm (7.9 to 23.6 in) in height and do not exceed one meter. The shrubbery consists of the species Pentzia monodiana, Artemisia tilhoana and Ephedra tilhoana. Finally, at the highest elevation elevations of the Tibesti, tree heath (Erica arborea) grows from moist crevices formed by early lava flows, and 24 different species of moss provide substrate for the tree heath.[51]

Fauna

The large mammals present in the ecoregion are the addax (Addax nasomaculatus), Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia), dorcas gazelle (Gazella dorcas), and rhim gazelle (Gazella leptoceros).[49] However, rodents are the most represented order of mammals in the Tibesti, and include the Agag gerbil (Gerbillus agag), Balochistan gerbil (Gerbillus nanus), Cairo spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus), lesser Egyptian jerboa (Jaculus jaculus), Libyan jird (Meriones libycus), Mzab gundi (Massoutiera Mzabi) and the North African gerbil (Gerbillus campestris).[49] Also present are cats such as the African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica) and, more rarely, the caracal (Caracal caracal) and the Sudan cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii), as well as several canine species including the Egyptian wolf (Canis anthus lupaster), fennec fox (Vulpes zerda) and Rüppell's fox (Vulpes rueppellii). The striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena) may also occupy the range.[49] There may be as many as 50 endangered painted hunting dogs (Lycaon pictus) in the Tibesti, although some regard these relict populations as extirpated, partially due to the Darfur refugee turmoil and other Sudan generated conflicts.[53] Bats are heavily represented in the Tibesti, including the desert long-eared bat (Otonycteris hemprichii), greater mouse-tailed bat (Rhinopoma microphyllum), Hamilton's tomb bat (Taphozous hamiltoni), Mauritian tomb bat (Taphozous mauritianus) and the trident bat (Asellia tridens).[49] The Cape hare (Lepus capensis), desert hedgehog (Paraechinus aethiopicus), olive baboon (Papio anubis), rock hyrax (Procavia capensis) and the Saharan striped polecat (Ictonyx libyca) also populate the area.[49]

Reptile and amphibian fauna is poor in the Tibesti range. There are gecko populations, including the Algerian sand gecko (Tropiocolotes steudneri), northern sand gecko (Tropiocolotes tripolitanus), Ragazzi's fan-footed gecko (Ptyodactylus ragazzii), ringed wall gecko (Tarentola annularis) and yellow fan-fingered gecko (Ptyodactylus hasselquistii). Snake species include the braid snake (Coluber rhodorachis), horseshoe whip snake (Hemorrhois hippocrepis), long-nosed worm snake (Leptotyphlops macrorhynchus), and the Saharan horn viper (Cerastes cerastes). Among the lizards are Bell's dabb lizard (Uromastyx acanthinura), Bibron's agama (Agama impalearis), the desert monitor (Varanus griseus), red spotted lizzard (Mesalina rubropunctata), and the sandfish (Scincus scincus).[49]

Many birds can be found in the Tibesti, as they nest or shelter there during migrations. These include the Abyssinian roller (Coracias abyssinicus), African black duck (Anas sparsa), anteater chat (Myrmecocichla aethiops), bar-tailed lark (Ammomanes cincturus), Barbary dove (Streptopelia risoria), Barbary partridge (Alectoris barbara), barn swallow (Hirundo rustica), black crake (Amaurornis flavirostra), blackstart (Cercomela melanura), blue rock thrush (Monticola solitarius), brown-necked raven (Corvus ruficollis), Cape teal (Anas capensis), common bulbul (Pycnonotus barbatus), common chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), common moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), common quail (Coturnix coturnix), cream-colored courser (Cursorius cursor), crested lark (Galerida cristata), crowned sandgrouse (Pterocles coronatus), desert lark (Ammomanes deserti), desert sparrow (Passer simplex), desert wheatear (Oenanthe deserti), eastern olivaceous warbler (Iduna pallida), Egyptian nightjar (Caprimulgus aegyptius), Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), Eurasian stone-curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus), fan-tailed raven (Corvus rhipidurus), fulvous babbler (Turdoides fulva), greater hoopoe-lark (Alaemon alaudipes), greater short-toed lark (Calandrella brachydactyla), helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris), hottentot teal (Anas hottentota), lanner falcon (Falco biarmicus), lappet-faced vulture (Torgos tracheliotus), laughing dove (Streptopelia senegalensis), Lichtenstein's sandgrouse ("Pterocles lichtensteinii), little owl (Athene noctua), northern wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe), Nubian bustard (Neotis Nuba), pallid swift (Apus pallidus), pygmy sunbird (Anthreptes platurus), red-billed teal (Anas erythrorhyncha), rock dove (Columba livia), rock martin (Ptyonoprogne fuligula), rufous-tailed scrub robin (Erythropygia galactotes), Rüppell's warbler (Sylvia rueppelli), sand martin (Riparia riparia), southern grey shrike (Lanius meridionalis), spotted sandgrouse (Pterocles senegallus), striolated bunting (Emberiza striolata), subalpine warbler (Sylvia cantillans), Sudan golden sparrow (Passer luteus), tawny eagle (Aquila rapax), trumpeter finch (Bucanetes githagineus), turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), western yellow wagtail (Motacilla flava) and the white-crowned wheatear (Oenanthe leucopyga).[49]

Fish survive in some rivers by gathering in gueltas during drought. The main species are Barbus anema, Barbus apleurogramma (East African red-finned barb), Barbus deserti, various Barilius species, Clarias gariepinus (African sharptooth catfish), Coptodon zillii (redbelly tilapia), Labeo annectens, Labeo niloticus (Nile carp), Labeo parvus, Labeobarbus batesii, and Sarotherodon galilaeus (mango tilapia).[23]

Population

The principal settlements in the Tibesti are Bardaï, Aozou and Zouar, respectively located in the center, north and west of the range, and each situated on oases along the enneris.[23] Bardaï, at an elevation of 1,020 m (3,350 ft), is the capital of Chad's Tibesti Region with around 1,500 inhabitants.[13][23] It is connected to Zouar by a track that crosses Tarso Toussidé. The village of Omchi is accessible from Bardaï via Aderké, or from Auzou via Irbi. These rough tracks extend southward towards Yebbi Souma and Yebbi Bou, and then follow the course of Enneri Misky. The eastern half of the Tibesti is cut off from the western half, as the eastern village of Aozi is accessible from Libya via Ouri.[52][54] Zouar has an airport,[55] as does Bardaï at Zougra.[56] Bardaï also has a hospital, although the medical supply is very much dependent upon the prevailing political situation.[8] In the early 1980s, the population of the Tibesti Mountains was estimated to number 8,000 which was dispersed among the interior valleys, outer slopes and plateaus. Around a quarter of the population was located around Zouar, 18% in the center and in the northeastern valley of the Enneri Bardagué where many palm trees are cultivated, 16% in the north around Aozou and the valley of the Enneri Yebige, and 7% on the plains. The remaining third of the population was dispersed among the tarsos.[57]

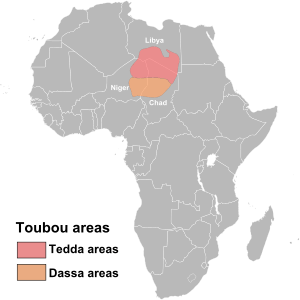

The vast majority of the population is Teda, one of the two ethnicities of the Toubou people. However, some clans are Daza, the other Toubou ethnicity, who left their traditional homes in the lowlands to the south and moved north to the Tibesti.[58] The Toubou, in general, are semi-nomadic[25][58] and live primarily in northern Chad, but also in southern Libya and eastern Niger. The Toubou language has two main dialects, Tedaga, spoken by the Teda, and Dazaga, spoken by the Daza. Despite their cultural proximity, the two Toubou groups do not identify as a single ethnic group.[59] The Toubou elect a chief, the Derdé, from the Tomagra clan, although never from the same family consecutively.[60][61] The Derdé resides in Zouar[48] and aims to impose religious and judicial authority over the Tibesti population;[60] however, efforts toward executive cooperation and war alliances are usually destined for failure.[62] The descendants of previous Derdé retain authority which transfers from father to son. These appointed Maïna govern portions of the Toubou territories.[48] Individual clans rarely have more than a thousand members and are quite dispersed throughout the Tibesti.[62]

Toubou life is punctuated by the seasons, divided between animal husbandry and agriculture.[25][63] In the palm groves, some Toubou still live in traditional round huts built with stone walls bound by mortar or clay, or built from clay or salt blocks,[64] with roofs of simple branches arranged in a dome shape.[25] In the highlands, the buildings are built of stone, forming circles 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in diameter and one metre (three ft) high, which serve as shelters for goats, or as granaries, or as human shelters and defense structures.[64] In other cases, the Toubou live in tents that can be easily moved between the fields and the palm groves.[59]

History

Human settlement

There is evidence of human occupation of the Tibesti dating back to the Stone Age, when richer paleovegetation facilitated human habitation.[42] The Toubou settled in the region in the 5th century BC[65] and established trade relations with the Carthaginian civilization.[66] Around this time, Herodotus portrayed the Toubou, which he labeled "Ethiopians" because of their skin color, and described as having a language akin to the "cry of bats."[9][65]

According to historian Raffael Joorde, a Roman traveler and diplomat named Julius Maternus explored with the king of the Garamantes the territory of the Tibesti mountains, while this king did a military campaign (or a "razzia") against rebellious subjects in the region an Agisymba[67]

In the 12th century, the geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi spoke of a "country of Zaghawa negroes", or camel herders, that had converted to Islam. The historian Ibn Khaldun described the Toubou in the 14th century. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Al-Maqrizi and Leo Africanus recognized the "country of the Berdoa", that is to say Bardaï, the former associating the Toubou with the Berbers and the latter describing them as Numidian relatives of the Taureg.[68]

The Toubou settled in the Tibesti in several waves. Generally, newcomers either killed or absorbed the previous clans after battles that were often both long-lasting and bloody.[69] The Teda clans, considered indigenous to the area, were first established around Enneri Bardagué. Namely, these clans were the Cerdegua, Zouia, Kossseda (nicknamed yobat or "hunters of well water"), and possibly the Ederguia, although the Ederguia's origin may be Zaghawa and only go back to the 17th century. These clans controlled the palm groves, and made a peace pact with the Tomagra, a nearby clan of camel herders who practiced Ghazw.[60] It was upon the agreement to this pact at the end of the 16th century that power was consolidated under the Derdé, the principal regulator of the clans, whose appointment is always made from the Tomagra clan.[60][70]

There is evidence of early Daza settlements in the Tibesti; however, these early clans—the Goga, Kida, Terbouna and Obokina—were assimilated into later Daza clans, who arrived in the Tibesti between the 15th and 18th centuries, having fled the Kanem-Bornu Empire in the southwest after the Toubou allied with a Kanem enemy, the Bilala.[60] These later Daza arrivals include the Arna Souinga in the south, Gouboda in the center-west, Tchioda and Dirsina in the west, Torama in the northwest and center-east, and the Derdekichia (literally, "descendants of the chief," the products of a union between an Arna Souinga and an Emmeouia) in the north. The Tibesti then played the role of an impregnable mountain stronghold for the newcomers.[71] Meanwhile, constant migration between the north and southwest of Chad, along with significant mixing of the populations, forged a significant degree of cohesion among the Toubou ethnicities. Periods of territorial expansion in the 10th and 13th centuries and periods of recession in the 15th and 16th centuries likely coincided with more or less pronounced wet and dry periods.[60][71]

Several clans with traditions similar to those of the Donzas of the Borkou region, south of the Tibesti, settled in the range in the 16th and 17th centuries. These include the Keressa and Odobaya in the west, Foctoa in the northwest and northeast, and Emmeouia in the north.[60] Several other clans—the Mogodi in the west, Terintere in the north, Tozoba in the center, and Tegua and Mada in the south—are originally clans of the Bideyat people who immigrated from the Ennedi Plateau, southeast of Tibesti, around the same time. The Mada, however, have since largely emigrated to Borkou, Kaouar and Kanem.[60]

The early 17th century also saw the arrival of three clans from the region of Kufra to the northeast. The Taïzera settled in the plateau in the center and west of the mass, probably fleeing the Arab push into present-day Libya. They were initially rejected by the Daza clans and lived in isolation until they began investing in the oases by planting numerous palms. The Mahadena occupy the northeast quarter of the range and are likely from the Cyrenaica and Jalu regions and thus related to the Mogharba Arab tribes, although an alternative hypothesis is that they are of Bideyat origin. Following years of conflict, a branch of the Mahadena clan, the Fortena, withdrew to the western margin of the Tibesti. The Fortena Mado ("Red Fortena") settled there, while the Fortena Yasko ("Black Fortena") pushed further west to Kaouar.[60]

The Tuareg people intermixed with the Toubou clans, especially with the early Goga clan, which produced the Gouboda, and with the later Arna clan, which produced the Mormorea. In both instances, the new clans were placed under the authority of suzerain clans of the traditionally feudal Tuareg, although they were eventually assimilated into the Toubou majority.[72] However, the Tuareg have not entered the Tibesti since the signing of a peace treaty that included mutual recognition of Toubou and Tuareg territories. The treaty was reaffirmed in 1820.[48]

Regional relations and colonization

The Ottoman Empire came into contact with the Toubou in 1560. Their relationship broke out into conflict in the late 17th century, with the Turks favoring the authority of local Maïna at the expense of the authority of the Derdé.[48] In 1780, the Derdé initiated an attack against the Ottomans. The Ottoman retaliation killed 60 percent the Toubou population.[48] The Teda then began launching attacks on Turkish caravans in an effort to disrupt Ottoman trade.[48] In 1890, Maï Getty Tchénimémi established diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire and began receiving firearms. Meanwhile, Derdé Chachaï allied with the Senussi Arabs and agreed that the southern half of the Tibesti could serve as a fallback base for the Senussi in their struggle against the French Colonial Army.[48][73] The Tibesti was then effectively split in two, with the "pro-Maï" in the southwest and the "pro-Derdé" in the northeast.[48] With the Derdé's blessing, the Senussi founded a Zawiya in Bardaï, which quickly promoted the total Islamization of the Tibesti.[10][48] At the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War, the Senussi allied with the Ottoman Empire and, at the request of the Derdé, the Turks established garrisons in Tibesti beginning in March 1911. These garrisons fell apart a few months later, and the Toubou attacked the Turkish troops.[73]

While the Italians occupied the Fezzan, a French column entered the Tibesti in early 1914 from Kaouar,[73] flouting an agreement with the Maï from the previous winter and forcing the Derdé Chachaï into exile.[48] The region was at the heart of the dispute between the colonial powers,[74] with the Italian Empire to the north and French West Africa to the south. During World War I, a Senussi revolt forced the Italians to temporarily withdraw from the Fezzan and the northeastern part of the range.[73] Maï Getty Tchénimémi allied with the supporters of the Derdé and led the resistance against the French troops until their withdrawal in 1916.[48] The Tibesti was reconquered by the French colonial empire in 1929, and the region was placed under the administration of French Equatorial Africa.[9][58][73]

Modern history

Chadian Civil War

Chad gained independence from France in 1960 and in 1965 the Chadian government led by François Tombalbaye imposed its administrative and judicial authority in the Tibesti. Mere days after the withdrawal of French troops from the region rebellion erupted in Bardaï, followed by numerous small-scale clashes over subsequent months and a more famous clash again in Bardaï in September. In response, the Tombalbaye government imposed travel and trade restrictions on the Toubou and voided the traditional power of the then Derdé, Oueddei Kichidemi.[70][75] Kichidemi went into exile in Libya the following year and became a national symbol in Chad for opposition to the government.[70] These events were a direct trigger of the First Chadian Civil War, which lasted from 1965 to 1979.[70][75]

In 1968, the French Army, at the request of Tombalbaye, intervened in an attempt to put an end to the rebellion, killing 25 rebels and 121 civilians in various towns, including Zouar.[48] However, the French leader of the intervention force, General Edouard Cortadellas, admitted that the Tibesti area was basically ungovernable, remarking, "I believe we should draw a line below [the Tibetsi region] and leave them to their stones. We can never subdue them." The French therefore concentrated its intervention to the center and the east of the country, leaving the Tibesti region area largely alone.[76]

In 1969, Goukouni Oueddei, a Teda leader, and Hissène Habré, a Daza leader, emerged from the Tibesti to form the Second Liberation Army, initially an arm of the National Liberation Front of Chad (FROLINAT) but which later broke from the group due to its close relationship with Libya. In April 1974, the Second Liberation Army captured Bardaï from the Chadian government and took hostage the French archeologist Françoise Claustre, German doctor Christophe Staewen and Marc Combe, an assistant to Claustre's husband, and held them in the mountains.[77][78] Staewen's wife and two soldiers of the Chadian army were killed.[78] The West German government quickly paid the ransom and Staewen was released. The French government sent the military officer Pierre Galopin to negotiate with the rebels, but he was captured by the rebels and executed in April 1975. Marc Combe was able to escape in May 1975. The remaining hostages were released in January 1977 in Tripoli after France acceded to the rebel's ransom demand.[79][80][81] The hostage incident, known as "L'affaire Claustre" served to further destabilize Chad.[77]

In 1976, the Second Liberation Army split into two factions, one affiliated with Libya and led by Goukouni, and the other led by Habré.[82] In June 1977, Goukouni's forces attacked Chadian government strongholds in Bardaï and Zouar, killing 300 government troops. Bardaï surrendered to the rebels on July 4, while Zouar was evacuated.[83] The government, led by Félix Malloum since Tombalbaye's overthrow in 1975, signed a peace agreement with Habré in 1978, although fighting with other rebel groups, many aligned with Libya, continued.[84][83]

Chadian–Libyan conflict

The Aouzou strip in the Tibesti region was defined for the first time in the discussions between France and Italy after World War I, in relation to an award to Italy for the victory in that war. At the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, France agreed to give some Saharan territories to Italian Libya: the area around Aouzou in the Tibesti region.

After many discussions during the 1920s, in 1935 the Franco-Italian Agreement was signed between Benito Mussolini and Pierre Laval, which included a provision under which Italy would receive the Aouzou strip, which was to be added to Libya. But the "instruments of ratification" of the Mussolini-Laval Treaty never were exchanged with France by the Italian Parliament (that wanted more territories). Despite this the new border was conventionally assumed to be the southern boundary of Libya until 1955, when the strip was returned to French Chad.

In 1978, Chad and Libya came into conflict over the Aozou Strip, a narrow, 114,000-square-kilometer (44,000 sq mi) borderland that extends into the Tibesti region and is supposedly rich in uranium deposits.[9][74] Prior to this, in 1972, the Chadian government under Tombalbaye had ceded the strip to Libya in a secret agreement with Libya's leader Muammar Gaddafi.[85] Following this agreement, Libya issued residents of the Aozou Strip Libyan identification cards.[77]

Following Libya's withdrawal from southern Chad in 1982, Habré's Armed Forces of the North (FAN) took control of the entirety of Chad with the exception of the Tibesti, where Goukouni remained with his Libyan-backed Government of National Unity (GUNT) forces.[86] Goukouni established a National Peace Government in Bardaï and proclaimed it the legitimate government of Chad. Habré attacked the GUNT in the Tibesti in both December 1982 and January 1983 but was repelled on both occasions. Although fighting intensified over the next several months, the mountains remained under the control of the GUNT and Libyan forces.[87]

Tibesti War

By 1986, following a series of military defeats, the GUNT had begun to disintegrate along with relations between Goukouni and Gaddafi. In August, Goukouni was arrested by the Libyans, which spurred his troops to attack Libyan positions in the Tibesti, forcing their withdrawal from the mountains. In October the remnant GUNT forces pledged themselves to Habré.[88]

Libya sought to retake Bardaï and Zouar, and sent a task-force of 2,000 troops with T-62 tanks and heavy support by the Libyan Air Force into the Tibesti. The offensive started successfully, expelling the GUNT from its key strongholds, aided by the use of napalm. The attack ultimately backfired, however, as it resulted in the prompt reaction of Habré, who sent 2,000 soldiers to support the GUNT forces.[89][90] Although the Libyans were only partially repelled from the Tibesti, the campaign was a great strategic victory, as it transformed a civil war into a national war against a foreign invader, stimulating a sense of national unity never before seen in Chad. After a series of defeats in northeastern Chad, Libyan forces withdrew fully from the Tibesti in March 1987.[91] Although the Tibesti has since entered an era of relative peace, the years of conflict have left the area strewn with thousands of landmines.[9][74]

Scientific exploration and research

Due to its isolation and geopolitical situation, the Tibesti Mountains were long unexplored by scientists.[12] The German Gustav Nachtigal, dispatched by Otto von Bismarck,[48] was the first European to explore, albeit with great difficulty, the Tibesti in 1869.[92] Prior to Nachtigal's expedition, an American along with two missionaries had attempted to enter the Tibesti range, but were killed by a Toubou warrior.[48] While Nachtigal provided an accurate description of the population, his account discouraged any new adventure into the Tibesti for over 40 years,[93] as he was convicted by the Toubou of spying for Bismarck and only released after the intervention of Maï Arami Tetimi.[48] Later expeditions carried out between 1920 and 1970 yielded valuable information on the geology and petrology of the range.[12] The French anthropologist Charles le Cœur and his wife Margaret, a geographer, lived among the Teda of Tibesti between 1933 and 1935. Le Cœur was the first to closely study the Tibesti populace, but the outbreak of World War II prevented him from publishing his research.[93] French Colonel Jean Chapelle published a book on the Toubou and their lifestyle in 1957.[93] In 1965, the Free University of Berlin opened a geomorphological research station in Bardaï; however, research at the station was interrupted several times due to the Chadian Civil War, and the station was ultimately closed in 1974.[94][95]

Although the Tibesti is one of the world's most significant examples of intracontinental volcanism, ongoing political instability and the presence of landmines means that, today, geologic research often must be conducted on the basis of satellite images and comparison with research on Martian volcanoes.[96] Little public geologic research had been conducted in the Tibesti Mountains until the work of Gourgaud and Vincent in 2004; however an expedition in 2015 sought to assess the feasibility of establishing a new geoscience research station in Bardaï.[74][97][98]

Climbing history

The first mountain to be climbed by a westerner in the Tibesti was Pic Toussidé in 1869 by Gustav Nachtigal during his exploration of the area, although the peak is not technically difficult.[99] In 1938, Emi Koussi was summited by Wilfred Thesiger.[100][101] The first sporting climb was probably that of the peak and needle of Botoum, at 2,400 m (7,900 ft) and 2,400 m (7,900 ft), respectively, by a Swiss expedition led by Edouard Wyss-Dunant in 1948.[99]

In 1957, P.R. Steele, R.F. Marks and W.W. Tuck of the University of Cambridge embarked on an expedition to Tarso Tieroko,[99] which Thesiger had described as "probably the most beautiful peak in Tibesti," and which offered an interesting climbing opportunity.[102] They started at the wadi Ybbu Bou and hired guides and camels for the three-day journey. Following a week of exploring the southern flank of the mountain and climbing the two peaks situated on a ridge to the north,[lower-alpha 4] they attempted to summit Tieroko from their camp at Wadi Modra. After ascending to an elevation of 3,200 m (10,500 ft), just 61 m (200 ft) from the summit, they were faced with a vertical, crumbling rock wall, and thus were forced to descend. Following this defeat, they took the opportunity to climb Emi Koussi, 19 years after its first ascent by Thesiger, and also Pic Woubou, a prominent spire located between Bardaï and Aozou.[102]

In 1962, the Swiss René Dittert and Robert Gréloz scaled Ou Obou, a 1,640 m (5,380 ft) peak.[99] In 1963, an Italian expedition led by Guido Monzino ascended Torre Innominata, a 970 m (3,180 ft) aiguille of Sissé, west of Tarso Toussidé.[99] In 2005, Bikku Bitti was scaled by Englishman Eamon "Ginge" Fullen and Chadian guides.[103][104] Due to the unstable political situation, the alpine conquest of the Tibesti Mountains remains very much incomplete.[99]

Economy

Natural resources

Although gold was long known to exist in small quantities, substantial deposits were discovered in 2012. Diamonds and emeralds have also been found. The mountains and their surroundings could contain significant quantities of uranium, tin, tungsten, niobium, beryllium, lead, zinc, copper, platinum, and nickel.[105][106][107][108] The natron extracted from Trou au Natron on Tarso Toussidé is used as a food supplement for animals.[106] The Soborom geothermal field, the name of which means "water cure," is known to locals for its medicinal qualities; the 42 °C (108 °F) pools are rumored to cure dermatitis and rheumatism after several days of soaking.[7][29] The Yerike hot spring is rich in natural gas;[29] its water temperature ranges between 22 and 88 °C (72 and 190 °F).[13][29]

Other than a nearby oasis, Mare de Zoui and its surroundings are rarely visited.[23] However, there are numerous small oases on the plains of Borkou, near Emi Koussi, which are extensively exploited. It is thought that water flows underground from the southern Tibesti mountains and then emerges in these springs.[23]

Agriculture

The oases to the west and north of the range have the easiest access. Where mosquitoes do not abound, they support several villages, such as Zouar, where indigenous plant species have largely been replaced by some 56,000 date palms (Phoenix dactylifera) for the production of dates.[23][57] These are harvested between late July and early August.[59] In winter, when reserves are depleted, it is not uncommon for the cores of the dates and the fiber of the palms to be ground into a paste and consumed.[57] These palm groves can also grow millet and corn, but the crop is spotty and sometimes swept away by early flooding.[59] The banks of the enneris grow desert gourd (Citrullus colocynthis), which are collected in October to extract the bitter seeds which, after being washed, are ground to make flour.[57][59] Horticulture is practiced on a small scale using traditional irrigation methods.[23] Goats and, more rarely, sheep number 50,000 heads, and 8,000 camels and 7,000 donkeys are raised in the range.[23][59] Chickens are also numerous,[108] although the consumption of meat is rare, usually done so through salting.[78]

Most animals spend the winter on the plateaus or in the high valleys. They descend into the lower valleys in February, just after the sowing of wheat, and then return in June to allow harvest.[59] In total, including barley, the Tibesti produces 300 tonnes (330 short tons) of cereals each year, which are mainly consumed in the form of cakes (dogo) and pancakes (fodack)[78] and complemented with wild grasses.[57] Women are responsible for gathering wild grains on the tarsos in August.[59] Fishing is possible in the water holes.[23] On the plains of Borkou, some fields are irrigated, where cattle, goats and camels can drink. Despite the date palm plantations, native species remain, such as the doum palm (Hyphaene thebaica), from which the sweet bark is collected, ground and consumed, despite its low nutritional value.[23] Agricultural product is traded once a year in exchange for fabrics.[59]

Tourism

Tibesti has tourism potential, with its primary attractions being the palm groves, rock and parietal art, canyons, basalt spires, volcanoes and hot springs.[108][109] However, the Zouar airfield cannot accommodate aircraft with more than a 20-seat capacity. This pushes the cost of air tickets from N'djamena up to 60 percent of the cost to fly from N'djamena to major European cities. Furthermore, tourist accommodations are virtually absent. As a result, the majority of tourists, most of whom are German, enter Libya, purchase all-terrain vehicles or caravans on the spot, and then cross the border into Chad. Thus, the economic benefits to Chad amount to only around 100 euros per tourist.[110] The presence of numerous landmines is a danger to tourists,[9][74] and thus hiking is generally limited to the southern end of the range. The ascent up Emi Koussi, around the Era Kohor, and then on to Yi Yerra hot springs generally takes about three days. The volcano has been climbed by 100 westerners since 1957.[111][112][113]

Conservation

A protected area in the Tibesti range has been proposed to preserve the area's rhim gazelle (Gazella leptoceros)[114] and Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) populations, which are the largest in the world.[115] The protected area would be modeled after the Ouadi Rimé-Ouadi Achim Faunal Reserve to the south; however, there is currently insufficient funding available for the project.[116]

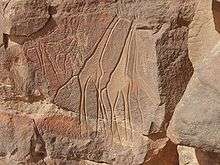

Culture

The Tibesti Mountains are renowned for their rock and parietal art. Around 200 engraving sites—including some 1800 different representations—and 100 painting sites have been identified. Most date from between the 5th and 3rd millennia BC, although some date from the 6th millennium BC, centuries before the arrival of the Toubou. The art has suffered the effects of time, including weathering from sand blown by the wind.[117][118][119] The earliest works often portray animals that have since died out due to climate change in the Tibesti, including elephants, rhinoceros, hippopotamus and giraffes. More recent art includes ostriches and antelopes, which have an exceptional presence on the edge of the range, as well as gazelles and sheep, which are more common.

Later works, dated less than 2000 years old, portray domesticated animals, such as oxen and camels. Other engravings portray warriors, known as owoza, dressed in feathers or spiked ornaments and armed with bows, shields, assegai, or traditional knives. Some portray dance scenes.[117][118][119] The walls of a canyon near Bardaï have engravings that measure over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height, including that of the "man of Gonoa," Gonoa being the name of the enneri that runs through the valley. These primarily show hunting scenes.[118] The paintings, often drawn with a red Faidherbia albida base, signify a turn towards domestication in the Tibesti, because the scenes are more pastoral.[118][119] The Tibesti art is unique in the Sahara because of the absence of inscriptions, the relative lack of chariots, and the low representation of camels and horses until comparatively recently.[118] The art has remained important to the Toubou; around 1200 AD, a man named Yerbou engraved a palm leaf into rock, symbolizing his love for a married woman.[120]

In 1989, French painter and sculptor Jean Vérame used the natural surroundings of the Ehi Kourné, a few kilometers south of Bardaï, to create multidimensional land art works by painting rocks. The project was supported by the Chadian president and the United Nations Development Programme, as well as private corporations such as the French oil company Total S.A. Over time, the Klein Blue paint turned patina white and red, and today is pinkish in color.[121][122][123]

The volcanic spires of the Tibesti, along with a stylized sheep's head, were displayed on a 20 CFA franc postage stamp issued by Republic of Chad in 1961.[124]

The Tibesti range was featured in the 1966 short story "Le Mura di Anagoor" ("The Walls of Anagoor") by the Italian novelist Dino Buzzati. In the story, a local guide offers to show a traveller the walls of a great city that is absent from the maps. The city is exceedingly opulent, yet exists in total autarky and does not submit to local authority. The traveler waits many years, in vain, to enter the Tibesti city.[125]

Notes and references

Notes

- An alternative theory holds that the name Toubou means "bird," because members of the Toubou communicate by whistling or because they run fast; however, it is unlikely that this theory is valid.[1]

- Although the official elevation of Emi Koussi is listed by the Institut Géographique National at 3,415 m (11,204 ft), data from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission suggests the peak is in fact 3,445 metres (11,302 ft).[15]

- Pic Toussidé is the highest point on the high plateau Tarso Toussidé.

- The two peaks are "The Imposter" and "Hadrian's Peak."

References

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-59884-362-0.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 611.

- Salam, M. J.; Hammuda, Omar S.; Eliagoubi, Bahlul A. (1991). The Geology of Libya, Volume 5. Elsevier. p. 1155. ISBN 978-0-444-88844-0.

- Sola, M.A.; Worsley, D., eds. (2000). Geological Exploration in Murzuq Basin. Elsevier. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-08-053246-2.

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2006). Tchad [Chad] (in French) (2nd ed.). Petit Futé. p. 22. ISBN 978-2-7469-1124-6.

- Beauvilain 1996, p. 15–20.

- Braquehais, Stéphanie (February 14, 2006). "Bardaï, village garnison au cœur du désert" [Bardaï, village garrison in the heart of the desert]. Radio France Internationale (in French). Archived from the original on February 18, 2011.

- Roure 1939.

- Bearman, P.J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (2005). Encyclopédie de l'Islam [Encyclopedia of Islam] (in French). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13951-0.

- Gourgaud and Vincent 2004, p. 261.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 609.

- Hughes and Hughes 1992, p. 1–3.

- Grande Encyclopédie 1979, p. 2262.

- "Africa Ultra-Prominences". Peaklist. December 3, 2011. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 615–616.

- "MousKorbe". Peakery. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21.

- "Kegueur Terbi". Peakery. Archived from the original on 2013-09-22.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 620–621.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 622.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 619.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 614.

- Hughes and Hughes 1992, p. 18–20.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 67.

- Grande Encyclopédie 1979, p. 2263.

- Getty Doby 2007, p. 8.

- "Emi Koussi". Global Volcanism Program.

- "Emi Koussi: Synonyms and Subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program.

- "Soborom". Wondermondo. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013.

- Pegram, W.J.; Register, J.K., Jr.; Fullagar, P.D.; Ghuma, M.A.; Rogers, J.J.W. (1976). "Pan-African ages from a Tibesti Massif batholith, southern Libya". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 30 (1): 123–128. Bibcode:1976E&PSL..30..123P. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(76)90014-5.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 616.

- El Makkrouf, Ali Ahmed (1988). "Tectonic interpretation of Jabal Eghei area and its regional application to Tibesti orogenic belt, south central Libya (S.P.L.A.J.)". Journal of African Earth Sciences (And the Middle East). 7 (7–8): 945–967. Bibcode:1988JAfES...7..945E. doi:10.1016/0899-5362(88)90009-7.

- Suayah, Ismail B.; Miller, Jonathan S.; Miller, Brent V.; Bayer, Tovah M.; Rogers, John J.W. (2006). "Tectonic significance of Late Neoproterozoic granites from the Tibesti massif in southern Libya inferred from Sr and Nd isotopes and U–Pb zircon data". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 44 (4–5): 561–570. Bibcode:2006JAfES..44..561S. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.11.020.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 620.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 621.

- Leenhardt, Olivier (2000). La catastrophe du lac Nyos au Cameroun [The Lake Nyos Disaster in Cameroon] (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 170. ISBN 978-2-7384-3690-0.

- Ceuleneer, Georges; Genthon, Pierre; Grégoire, Michel; Monnereau, Marc; Ormond, Anne; Rabinowicz, Michel; Toplis, Mike (2006). "Pétrologie et géodynamique comparée" (PDF). Rapport d'activité 2002–2005 de l'UMR5562 et prospective 2007–2010 [2002–2005 Activity Report of UMR5562 and 2007–2010 Prospective] (in French). Laboratoire Dynamique Terrestre et Planétaire. p. 87. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-04.

- Kochemasov, G.G. (2007). "The Cameroon line: its regularities and relation to African rifts". Global Tectonics and Metallogeny. 9 (1–4): 67–72. ISSN 0163-3171.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 617–619.

- Cheminée, Jean-Louis (1996). Les Volcans [Volcanoes] (in French). Chamalières. p. 113. ISBN 978-2-7344-0757-7.

- "Tarso Toussidé". Global Volcanism Project.

- Hagedorn, H. (1997). "Tibesti". In Tillet, Thierry (ed.). Sahara : paléomilieux et peuplement préhistorique au Pléistocène supérieur [Sahara: paleoenvironments and prehistoric populations in the Upper Pleistocene] (in French). L'Harmattan. pp. 267–273.

- Soulié-Märsche, I.; Bieda, S.; Lafond, R.; Maley, J.; M'Baitoudji, M.; Vincent, P.M.; Faure, Hugues (2010). "Charophytes as bio-indicators for lake level high stand at "Trou au Natron", Tibesti, Chad, during the Late Pleistocene". Global and Planetary Change. 72 (4): 334–340. Bibcode:2010GPC....72..334S. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2010.05.004.

- Maley, Jean (2000). "Last Glacial Maximum lacustrine and fluviatile Formations in the Tibesti and other Saharan mountains, and large-scale climatic teleconnections linked to the activity of the Subtropical Jet Stream". Global and Planetary Change. 26 (1–3): 121–136. Bibcode:2000GPC....26..121M. doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(00)00039-4.

- Tourte, René (2005). Histoire de la recherche agricole en Afrique tropicale francophone [History of agricultural research in French tropical Africa] (in French). Volume I: Aux sources de l'agriculture africaine: de la Préhistoire au Moyen Âge. Food and Agriculture Organization. p. 11. ISBN 978-92-5-205407-8.

- Messerli, B. (1973). "Problems of vertical and horizontal arrangement in the high mountains of the extreme arid zone (central Sahara)". Arctic and Alpine Research. 5 (3): A140. ISSN 0004-0851. JSTOR 1550163.

- "Climate Data for Latitude 21.25 Longitude 17.75". Global Species. July 28, 2011.

- "Présentation". Zouar.net. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011.

- "Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Giazzi, Frank (1996). La Réserve Naturelle Nationale de l'Aïr et du Ténéré (Niger) : la connaissance des éléments du milieu naturel et humain dans le cadre d'orientations pour un aménagement et une conservation durables : analyse descriptive [The National Nature Reserve of the Aïr and Ténéré (Niger): The elements of the natural and human environment within a framework of sustainable conservation management: descriptive analysis] (in French). International Union for Conservation of Nature. p. 179. ISBN 978-2-8317-0249-0.

- White 1998, p. 243–244.

- Getty Doby 2007, p. 11.

- Hogan, C. Michael (January 31, 2009). "African Wild Dog". GlobalTwitcher.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013.

- Tilho, Jean (1920). Carte provisoire de la région Tibesti. Borkou, Erdi, Ennedi, (mission de l'Institut de France, 1912–1917) (Map). Service géographique de l'armée.

- Getty Doby 2007, p. 31.

- "Bardai Zougra Airport". Airports Database.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 69.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 2, 6.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 70.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 72–79.

- Baroin, Catherine (1985). Anarchie et cohésion sociale chez les Toubou: les Daza Kéšerda (Niger) [Anarchy and social cohesion among the Toubou: Daza Kešerda (Niger)] (in French). Editions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. ISBN 978-2-7351-0095-8.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 38.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 4–5.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 30–31.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 36–37.

- "Le Tibesti". Visiter le Tchad. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012.

- Raffael Joorde." Römische Vorstöße ins Innere Afrikas südlich der Sahara: die geheimnisvolle Landschaft Agisymba", Dortmund, 2015 ()

- Chapelle 2004, p. 34–35.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 81–82.

- "Chad: Toubou and Daza: Nomads of the Sahara". A Country Study: Chad. Library of Congress. LCCN 89600373.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 41–44.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 79–81.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 64.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 610.

- Fearon et al. 2006, p. 4.

- Fearon et al. 2006, p. 6.

- Fearon et al. 2006, p. 10.

- "Teda, Toubou, Tubu". Zouar.net. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- Claustre, Pierre (1990). L'Affaire Claustre: autopsie d'une prise d'otages [The Claustre Affair: Autopsy of a hostage situation] (in French). Karthala. ISBN 978-2-86537-258-4.

- Arsenault, Claire (September 6, 2006). ""La captive du désert" est morte" [The "captive of the desert" is dead] (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011.

- Correau, Laurent (August 18, 2008). "1974–1977 L'affaire Claustre et la rupture avec Habré" [1974–1977 The Claustre affair and break with Habré] (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012.

- Fearon et al. 2006, p. 11.

- Higgins, Rosalyn (July 2, 1993). "The Reactions of Chad to the Libyan Occupation" (PDF). Public sitting held on Friday 2 July 1993, at 10 a.m., at the Peace Palace, President Sir Robert Jennings presiding in the case concerning Territorial Dispute (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Chad). The Hague: International Court of Justice. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2001. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- Fearon et al. 2006, p. 10–11.

- Nolutshungu 1995, p. 327.

- Nolutshungu 1995, p. 186.

- Nolutshungu 1995, p. 188.

- Nolutshungu 1995, p. 213–214.

- Nolutshungu 1995, p. 214–216.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (2002). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. University of Nebraska Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-8032-3733-9.

- Nolutshungu 1995, p. 215–216, 245.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 10.

- Baroin, Catherine (2003). Du sable sec à la montagne humide, deux terrains à l'épreuve d'une même méthodologie [Dry sand to damp mountain, two sites tested with the same methodology] (PDF) (in French). Université de Paris X - Nanterre.

- Jäkel, Dieter (1977). "The Work of the Field Station at Bardai in the Tibesti Mountains". The Geographical Journal. 143 (1): 61–72. doi:10.2307/1796675. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1796675.

- Klitzsch, Eberhard H. (2004). "From Bardai to SFB 69: The Tibesti Research Station and Later Geoscientific Research in Northeast Africa" (PDF). Die Erde. 135 (3–4): 245. ISSN 0013-9998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- Permenter and Oppenheimer 2007, p. 609–610.

- Gourgaud and Vincent 2004, p. 261–290.

- University of Cologne (June 2, 2015). "Scientific Exploration of the Tibesti Mountains: Cologne Researcher Headed Mission to the Peaks of the Sahara Desert". Science Daily. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Grande Encyclopédie 1979, p. 2264.

- "Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003)" (in French). Les Deserts.

- "Emi Koussi". Peakware. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012.

- Steele, P.R. (1964). "A Note on Tieroko (Tibesti Mountains)". Alpine Journal. 69 (308–309).

- "Fastest time to climb the highest peaks in all African countries". Guinness World Records.

- Fullen, Ginge (September 5, 2007). "Libya - Bikku Bitti". SummitPost.org.

- Chamberlain, Gethin (January 17, 2018). "The deadly African gold rush fuelled by people smugglers' promises". The Guardian. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Bangoura, Mohamed Tétémadi (2005). Violence politique et conflits en Afrique: le cas du Tchad [Political violence and conflict in Africa: the case of Chad] (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-00079-7.

- Maoundonodji, Gilbert (2009). Les enjeux géopolitiques et géostrategiques de l'exploitation du pétrole au Tchad [The geopolitical and geostrategic issues of the exploitation of oil in Chad] (in French). Presses universitaires de Louvain. ISBN 978-2-87463-171-9.

- "Economie". Zouar.net. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- "Info voyage Tchad, séjour, circuit désert du Tchad, hôtels à N'djamena, Moundou, Sarh et Abéché au Tchad, parcs naturel Zakouma - l'ancêtre Toumai" [Chad travel info, holiday, around the Chadian desert, N'djamena hotels, Moundou, Sarh and Abeche in Chad, Zokouma National Park - the ancient Toumai] (in French). Tourisme en Afrique. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012.

- Getty Doby 2007, p. 31–34.

- Nicolazzi, Anthony (March 1, 2010). "Hommes et Montagnes signe son retour à l'Emi Koussi" [Men and Mountains sign his return to Emi Koussi] (in French). Trek Magazine.

- Olimori (December 5, 2008). "Vers l'Emi Koussi" [Towards Emi Koussi] (in French). I-Trekkings.net. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013.

- "Tibesti, Emi Koussi et lacs d'Ounianga" [Tibesti, Emi Koussi and lakes of Ounianga] (in French). Terres d'Aventure. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- Beudels, Marie-Odile (January 30, 2008). "Chad". Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Archived from the original on November 27, 2007.

- Baseline Study C: Etude de l'état des instruments politiques, capacités institutionnelles et niveaux de sensibilisation en relation avec les changements climatiques et les aires protégées en Afrique de l'Ouest: Gambie, Mali, Sierra Leone, Tchad et Togo [Baseline Study C: Study of state policy instruments, institutional capacity and awareness levels in relation to climate change and protected areas in West Africa: Gambia, Mali, Sierra Leone, Chad and Togo] (PDF) (in French). United Nations Environment Programme. September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-21.

- Rapport de mission: Prospections des zones prioritaires de conservation pour les Antilopes Sahélo-Sahariennes au Tchad, et identification de programmes de conservation/développement durable [Mission Report: Surveys of priority conservation areas for the Sahel-Saharan Antelopes in Chad, and identification of programs for sustainable conservation/development] (PDF) (in French). Bonn Convention. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-21.

- Chapelle 2004, p. 27–28.

- Beauvilain 1996, p. 21–24.

- Getty Doby 2007, p. 13.

- Getty Doby 2007, p. 14.

- "Jean Verame" (in French). Encyclopedie Audiovisuelle De L'art Contemporain. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012.

- "Jean Verame" (in French). JeanVerame.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2013-05-21.

- "Bardaï Mue". Geo212. Archived from the original on January 29, 2012.

- "Timbre: Head of sheep and Tibesti". Colnect.com.

- Buzzati, Dino; Breitman, Michael (1984) [1966]. "Les Murs d'Anagoor". Les Sept messagers: nouvelles [The Seven Messengers: short stories] (in French). Union générale d'éditions. ISBN 978-2-264-00478-9.

Bibliography

- Beauvilain, Alain (1996). Pages d'histoire naturelle de la terre tchadienne [The Natural History of the Chadian Land] (PDF) (in French). Centre national d'appui à la recherche. OCLC 54307645.

- Chapelle, Jean (2004) [1982]. Nomades noirs du Sahara : les Toubous [Black nomads of the Sahara: the Toubou] (in French). Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-85802-221-2.

- Getty Doby, Jomode Elie (2007). Le développement du tourisme durable au Tchad [The development of sustainable tourism in Chad] (PDF) (in French). Institut d'études politiques de Toulouse. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- Fearon, James; Laitin, David; Kasara, Kimuli (July 7, 2006). "Chad" (PDF). Stanford University.

- Gourgaud, A.; Vincent, P. M. (2004). "Petrology of two continental alkaline intraplate series at Emi Koussi volcano, Tibesti, Chad". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 129 (4): 261–290. Bibcode:2004JVGR..129..261G. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(03)00277-4.

- Grande Encyclopédie de la Montagne [Great Encyclopedia of the Mountains] (in French). Volume 8: Row-Zwil. Éditions Atlas. 1979. OCLC 461745836.

- Hughes, R.H.; Hughes, J.S. (1992). "Chad" (PDF). A Directory of African Wetlands. World Conservation Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-24.

- Johnston, Harry Hamilton (1969) [1910]. Britain across the seas: Africa: a history and description of the British Empire in Africa. New York: Negro Universities Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-1344-9.

- Permenter, Jason L.; Oppenheimer, Clive (2007). "Volcanoes of the Tibesti massif (Chad, northern Africa)". Bulletin of Volcanology. 69 (6): 609–626. Bibcode:2007BVol...69..609P. doi:10.1007/s00445-006-0098-x.

- Nolutshungu, Sam C. (1995). Limits of Anarchy: Intervention and State Formation in Chad. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1628-3.

- Roure, Gil (April 1, 1939). "Le Tibesti, bastion de notre Afrique Noire" [The Tibesti, bastion of our Black Africa] (PDF). L'Illustration (in French) (5013). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016.

- White, F. (1998) [1986]. La Végétation de l'Afrique: Mémoire accompagnant la carte de végétation de l'Afrique [The Vegetation of Africa: Report accompanying a vegetation map of Africa] (in French). Institut de Recherche pour le Développement. ISBN 978-2-7099-0832-0.

External links

- Information on climbing, with map

- Information about the mountains, with images

- "Tibesti region". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Travel page with photos (in German)

- Report of a recent (2014) expedition to the Tibesti

.jpg)

.jpg)

_2.jpg)

.jpg)