Charles Bean

Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (18 November 1879 – 30 August 1968), usually identified as C. E. W. Bean, was an Australian World War I war correspondent and historian.[1]

Charles Bean | |

|---|---|

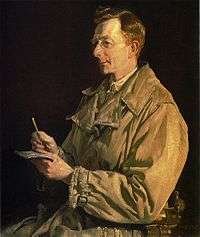

Portrait by George Lambert, 1924 | |

| Born | Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean 18 November 1879 |

| Died | 30 August 1968 (aged 88) |

| Awards | Chesney Gold Medal (1930) |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

| Influences | Banjo Paterson |

| Academic work | |

| Main interests | Australian military history First World War |

| Notable works | Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 |

| Influenced | Gavin Long Bill Gammage |

Bean is remembered as the editor of the 12-volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 and was instrumental in the establishment of the Australian War Memorial, and of the creation and popularisation of the ANZAC legend.

Early life and education

Bean was born in Bathurst, New South Wales,[1] a son of the Reverend Edwin Bean, headmaster of All Saints' College.[2] Bean's mother, Lucy Madeline Bean, née Butler, was born in 1852 and died on 18 March 1942. The couple had three sons: Charles Edward Woodrow Bean, M.A., B.C.L. (18 November 1879 – 30 August 1968); Dr. John Willoughby Butler Bean B.A, M.D., B.Ch. (1 January 1880 – 1969), who was a medical practitioner; and Montague Butler Bean (1884–1964), who was an engineer.

Both of Bean's parents lived their last years at Sandy Bay Road, Hobart, Tasmania, the state of his mother's birth. Bean's father, Edwin Bean, died in 1922. In an obituary the son described his father's achievements, which were many, as well as his shortcomings, raising the article to something above the usual eulogy.[3]

In 1889, the family moved to England, where Bean was educated, first at Brentwood School in Essex, where his father was headmaster, then from 1894 at Clifton College, Bristol,[4] before winning a scholarship in 1898 to Hertford College, Oxford, where he took an MA and B.C.L. and was called to the bar in 1903.[5]

Early career

Bean returned to Australia in 1904 and taught briefly, including a stint at Sydney Grammar School,[2] then worked as a legal assistant on a country circuit from 1905 to 1907. He resigned his position as barrister assisting Mr. Justice Owen in May 1907,[6] and recounted his experiences in The Sydney Morning Herald in a series of articles. In June 1908, he joined The Sydney Morning Herald as a reporter. By mid-1909, he was working on commissioned articles; the first was "The Wool Land", in three weekly instalments.[7][8][9]

It was during this period of travelling the outback of New South Wales that Bean took two journeys on the paddle steamer Jandra,[10] which he recounted in Dreadnought of the Darling, serialised in the Sydney Mail in 1910, then published in book form in 1911.

In 1911 and 1912, he was the Herald's correspondent in London. Again, he made good use of his opportunities, producing a series of articles which he fleshed out for his next book Flagships Three, which received favourable reviews.[11]

World War I

After the declaration of war by the British Empire upon the German Empire on 4 August 1914, Bean secured an appointment as the official war correspondent to the Australian Imperial Force in September, having been selected for the post by the executive council of the Australian Journalists' Association, narrowly beating Keith Murdoch.[1][12] He was commissioned at the rank of captain in the A.I.F. and reported all of the major campaigns where Australian troops saw action in the conflict.

Gallipoli Campaign

Bean went ashore at Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula at 10 a.m. on 25 April 1915, a few hours behind the seaborne landing of the first troops, and provided press reports of the experiences of the Australians there for most of the campaign.

As a war correspondent, Bean's copy was detailed and accurate, but lacked the exciting narrative style of the English war correspondents like Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, who produced the first eyewitness report from the peninsula theatre, which was published in Australian newspapers on 8 May 1915. As demand for reports on the events at Gallipoli increased in the Australian home audience, domestic newspapers such as The Age and The Argus stopped carrying Bean's copy due to its unappealing style.

In early May, Bean travelled to Cape Helles with the 2nd Infantry Brigade to cover the Second Battle of Krithia. When the brigade was called to advance late in the afternoon on 8 May 1915, Bean went with them from their reserve position to the starting line for the attack and found himself under enemy fire for the first time (in the form of artillery shrapnel shells). Here he was recommended for the Military Cross for gallantry under fire in rescuing a wounded soldier but was ineligible as his military rank was only honorary.[13] While under fire at this action Bean abandoned his observer status and involved himself in the proceedings by carrying messages between the brigade commander Brigadier General James M'Cay and elements of the formation; he also traversed the battlefield delivering water to the men in the parched conditions and helping to carry the wounded, including the Commanding Officer of the 6th Battalion, A.I.F., Lieutenant Colonel Walter McNicoll.

On the night of 6 August 1915, Bean was hit in the leg by a Turkish bullet while following the column of Brigadier-General John Monash's 4th Infantry Brigade at the opening of the Battle of Sari Bair. Despite the wound, he refused to be medically evacuated,[14] and continued with his role reporting on the dying Gallipoli campaign's final phase of defeat and the abandonment and withdrawal from the Peninsula by the British Imperial Forces.

Bean left Gallipoli on the night of 17 December 1915, two nights before the final evacuation of Anzac Cove by the A.I.F. He returned to it after the war, in 1919, with the Australian Historical Mission.

Western Front

In 1916, Bean went with the Australian Imperial Force as it moved from the Mediterranean theatre of operations to France after the failure of the Gallipoli campaign.[1] He reported from all but one of the engagements involving Australian troops, observing first hand the "fog of war", the problems in maintaining communication between the commanders in the rear and the front line troops, and between isolated units of front line troops, and the technological problems that existed midway through the war in co-ordinating activities of the infantry forces with other arms of the service such as artillery, and with separate forces on each flank of units engaged. His reporting detailed also how accounts given by front line troops, and captured German soldiers, could sometimes be misleading as to the actual course of events given their limited perspective on the battlefield, and also on the effects of the shell-shock from the devastating artillery fire.

It was during his time with the A.I.F. on the Western Front that Bean began thinking about the historical preservation of the Australian experiences of the conflict with the establishment of a permanent museum and national war memorial, and collection of a record of the events. (Concurrent with Bean's thoughts along these lines, on 16 May 1917 the Australian War Records Section was established under the command of Captain John Treloar to manage the collection of documents relating to the conflict and important physical artefacts. Attached with the Section's work were members of the Australian Salvage Corps who were charged with locating items judged to be of historical interest from the wreckage they were processing from the battlefields for scrap or repair.)

Bean had a £15 clothing allowance[15] from the Australian Government, expending it upon what would become his 'distinctive outfit'. He was also equipped with a horse and saddlery. Private Arthur Bazley was assigned as Bean's batman, and the two became friends.

Bean's influence amid the Australian war effort grew as the war progressed, and he used it to argue within Australian Government circles unsuccessfully against the appointment of General John Monash to the command of the Australian Corps in 1918. He expressed anti-semitic views about Monash and his perceived favouritism in the way that he dispensed promotions.[16] (Monash was Jewish) and Bean described him as a "pushy Jew".[17] Bean had earned Monash's wrath in return for failing to give his command the publicity that Monash thought it deserved during the Gallipoli campaign. Bean distrusted what he felt was Monash's penchant for self-promotion, writing in his diary: "We do not want Australia represented by men mainly because of the ability, natural and inborn in Jews, to push themselves forward". Bean favoured the appointment of the Australian Chief of General Staff, Brudenell White, the meticulous planner behind the withdrawal from Gallipoli or General William Birdwood, the English Commander of the Australian forces at Gallipoli. Despite his opposition to the appointment of Monash, Bean later acknowledged his success in the role, noting that he had made a better corps commander than a brigadier, admitting that his role in trying to influence the decision had been improper.

Bean's brother was an anaesthetist and served as a Major in the Medical Corps on the Western Front.

Post-war

In 1916, the British War Cabinet had agreed to grant Dominion official historians access to the war diaries of all British Army units fighting on either side of a Dominion unit, as well as all headquarters that issued orders to Dominion units, including the GHQ of the British Expeditionary Force. By the end of the war, the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) were less than willing to divulge this information, possibly fearing it would be used to criticise the conduct of the war. It took six years of persistence before Bean was allowed access and a further three years for a clerk to make copies of the enormous quantity of documents. Bean therefore had available to him resources that were denied to all British historians who were not associated with the Historical Section of the CID.

Bean was unwilling to compromise his values for personal gain or political expediency. He was not influenced by suggestions and criticism from British official historian, Sir James Edmonds about the direction of his work. Edmonds reported to the CID that, "The general tone of Bean's narrative is deplorable from the Imperial standpoint." For his maverick stance, it is likely that Bean was denied decorations from King George V, despite being recommended on two occasions during the war by the commander of the Australian Corps. Bean was not motivated by personal glory; many years later when he was offered a knighthood, he declined.[18]

In 1919, Bean led the Australian Historical Mission back to the Gallipoli peninsula to revisit the battlefield of 1915. For the first time he was able to walk over ground where some of the famous battles were fought such as Lone Pine and at the Nek, where he found the bones of the light horsemen still lying where they fell on the morning of 7 August 1915. He also instructed the Australian Flying Corps, one of the few Australian units involved in the occupation forces in Germany, to collect German aircraft to be returned to Australia; they obtained a Pfalz D.XII and an Albatros D.Va.

Upon his return to Australia in 1919, Bean commenced work with a team of researchers on the Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–18; and the first volume, covering the formation of the AIF and the landing at Anzac Cove, was published in 1921. It would be 21 years before the last of the 12 volumes (Volume VI) was published. Bean personally wrote the first 6 volumes covering the Army involvement. In 1946 he published Anzac to Amiens, a condensed version of the Official History – this was the only book to which he owned the copyright and received royalties.

Bean's style of war history was different from anything that had gone before. Partly reflecting his background as a journalist, he concentrated on both the 'little people' and the big themes of the First World War. The smaller size of the Australian Army contingent (240,000) allowed him to describe the action in many cases down to the level of individuals, which suited Bean's theme that the achievement of the Australian Army was the story of those individuals as much as it was of generals or politicians. Bean was also fascinated by the Australian character, and used the history to describe, and in some way create, a somewhat idealised view of an Australian character that looked back at its British origins but had also broken free from the limitations of that society. "It was character", he wrote, "which rushed the hills at Gallipoli and held on there during the long afternoon and night, when everything seemed to have gone wrong."[19]

Bean's approach, despite his prejudices and his intention to make the history a statement about society, was meticulously to record and analyse what had happened on the battlefields. His method was generally to describe the wider theatre of war, and then the detailed planning behind each battle. He then moved to the Australian commander's perspectives and contrasted these with the impressions from the troops at the front line (usually gathered by Bean 'on the spot'). He then went further and quoted extensively from the German (or Turkish) records of the same engagement, and finally summarised what had actually happened (often using forensic techniques, going over the ground after the war). All throughout he noted the individual Australian casualties where there was any evidence of the circumstances of their death. Even with that small contingent of 240,000 (of whom 60,000 died) this was a monumental task. Bean also – uniquely – reported ultimately on his own involvement in the manoeuvring around command decisions regarding Gallipoli, and the appointment of the Australian Corps Commander, and did not spare himself some criticism with the wisdom of hindsight.

Bean's style of writing profoundly influenced subsequent Australian war historians such as Gavin Long (who was appointed on Bean's recommendation), and the Second World War series, describing the battles of North Africa, Crete, New Guinea and Malaya, retain Bean's commitment to telling the story of individuals as well as the bigger story.

Australian War Memorial

Bean played an essential role in the creation of the Australian War Memorial.[20] After experiencing the First World War as the official Australian war historian, he returned to Australia determined to establish a public display of relics and photographs from the conflict. Bean dedicated an enormous portion of his life to the development of the Australian War Memorial, located in Canberra and now one of Australia's major cultural icons.

It was during the time spent with the First Australian Imperial Force in Europe that Bean started thinking seriously about the need for an Australian war museum. A close friend of his during this time, A.W. Bazley, recalled that "on a number of occasions he talked about what he had in his mind concerning some future Australian war memorial museum". Bean envisioned a memorial that would not only keep track of and hold records and relics of war, but would also commemorate the Australians who lost their lives fighting for their country.

In 1917, as a result of Bean's suggestions to the Defence Minister, Senator George Pearce, The Australian War Records Section was established. The AWRS was set up to guarantee that Australia would have its own collection of records and relics of the First World War being fought. This department arranged for the collection of relics from the field, and the appointment of official war photographers and artists. Many of the numerous relics collected, and photographs and paintings produced, can be seen in the Australian War Memorial today. The quality of paintings from the First World War is attributed in large part to the "quality control" exercised by Bean.[20]

The basis of the building known today as the Australian War Memorial was completed in 1941. The Memorial's website describes the building plan as "a compromise between desire for an impressive monument to the fallen and a budget of only £250,000". Bean's dream of a memorial in recognition of Australian soldiers who fought in the Great War had finally been realised. However, when it was realised that the Second World War was of a magnitude to match that of the First, it was understood that the memorial would have to also commemorate servicemen from the latter conflict, despite the original intentions.

The Hall of Memory, completed in 1959, could not have fulfilled Bean's dream of commemoration more completely. It adhered to Bean's view that war should not be glorified, but that those who died fighting for their country should be remembered. Bean's moral principles such as this, and the fact that the enemy should not be referred to in derogatory terms, along with many others, greatly influenced the philosophical angle that the Australian War Memorial has always taken, and would continue to take.

Bibliography

- With the flagship in the South (1909)

- On the Wool Track (1910)

- The Dreadnought of the Darling (1911)

- Flagships Three (1913)

- The Anzac Book (Ed., 1916)

- Letters from France (1917)

- In Your Hands, Australians (1918)

- Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918

- Volume I – The Story of Anzac: the first phase (1921)

- Volume II – The Story of Anzac: from 4 May 1915 to the evacuation (1924)

- Volume III – The Australian Imperial Force in France: 1916 (1929)

- Volume IV – The Australian Imperial Force in France: 1917 (1933)

- Volume V – The Australian Imperial Force in France: December 1917 – May 1918 (1937)

- Volume VI – The Australian Imperial Force in France: May 1918 – the Armistice (1942)

- (A further six volumes were the work of other authors with Bean having varying degrees of involvement)

- Anzac to Amiens (1946)

- Here, My Son (1950)

- Two Men I Knew (1957)

Personal life

Bean married Ethel Clara "Effie" Young of Tumbarumba on 24 January 1921. She died in the 1990s.

See also

- Military attachés and war correspondents in the First World War

References

Citations

- Reid, John B. (1977). Australian Artists at War, Vol. 1, p. 12.

- "C. E. W. Bean". The Western Herald, Bourke. Bourke, NSW: National Library of Australia. 10 October 1958. p. 3. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Edwin Bean, Great Headmaster". The Sunday Times. Sydney: National Library of Australia. 3 September 1922. p. 13. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J. A. O. p. 188: Bristol; J. W. Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April, 1948

- William H. Wilde, Joy Hooton and Barry Andrews eds. The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature 2nd edition 1994, Oxford University Press, Melbourne ISBN 0 19 553381 X

- "Personal". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 1 May 1907. p. 9. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "The Wool Land I." The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 10 September 1909. p. 6. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "The Wool Land II". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 17 September 1909. p. 6. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "The Wool Land III". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 24 September 1909. p. 7. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- The Darling river seen from the paddle-steamer Jandra. One of a series of photographs taken by C. E. W. Bean during two trips he made in 1908 and 1909 to regional NSW as a journalist for the Sydney, retrieved 26 April 2020

- "Reviews of Books". South Australian Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 9 August 1913. p. 4. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Australian War Correspondent". The Brisbane Courier. National Library of Australia. 28 September 1914. p. 7. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Carlyon, p. 248.

- Carlyon, p. 378.

- As an indication of the purchasing power of £15, it would in 1915 buy six three-piece suits or twelve pairs of superior tan leather boots (50s. and 25s. respectively).

- Dapin, Mark. "War historian Charles Bean caught up in his own war of words". The Australian.

- Wright, Tony (17 April 2018). "Sir John Monash was familiar with the brush-off 100 years ago". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- Inglis, K.S. (1979). "Bean, Charles Edwin Woodrow (1879–1968)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 19 March 2008 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- J. Franklin, Corrupting the Youth: A History of Philosophy in Australia (Macleay Press, 2003), ch. 10.

- Reid, p. 7.

Sources

- Carlyon, Les (2014) [2001]. Gallipoli. Sydney, New South Wales: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-74353-422-9.

- Inglis, Ken. (1979). "Bean, Charles Edwin Woodrow (1879–1968)," Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 9780522841855; OCLC 185989559

- Reid, John B. (1977). Australian Artists at War: Compiled from the Australian War Memorial Collection. Volume 1. 1885–1925; Vol. 2 1940–1970. South Melbourne, Victoria: Sun Books. ISBN 9780725102548; OCLC 4035199

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Bean. |

- Australian War Memorial: Charles Bean biography

- Australian War Memorial: Notebooks, Diaries and Folders of C.E.W. Bean

- Australian War Memorial: First World War Official Histories ed. C.E.W. Bean

- Pegram, Aaron: Bean, Charles, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Works by Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Bean at Internet Archive

- Inglis, K.S. (1979). "Bean, Charles Edwin Woodrow (1879–1968)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 19 March 2008 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.