South West Queensland

South West Queensland is a remote region in the Australian state of Queensland which covers 319,808 km2 (123,479 sq mi).[1] The region lies to the south of Central West Queensland and west of the Darling Downs and includes the Maranoa district and parts of the Channel Country. The area is noted for its cattle grazing, cotton farming, opal mining and oil and gas deposits.

| South West Queensland Queensland | |

|---|---|

Regions of Queensland | |

| Population | 26,489 (2011)[1] |

| • Density | 0.0828278/km2 (0.214523/sq mi) |

| Area | 319,808 km2 (123,478.6 sq mi) |

| LGA(s) | Maranoa Region, Shire of Balonne, Shire of Paroo, Shire of Murweh, Shire of Bulloo, Shire of Quilpie |

| State electorate(s) | Warrego |

| Federal Division(s) | Maranoa |

At the federal level the whole region is encompassed by the Division of Maranoa. Local Government areas included in the region are Maranoa Region, Shire of Balonne, Shire of Paroo, Shire of Murweh, Shire of Bulloo and the Shire of Quilpie. South West Queensland has a population of 26,489.[1]

The region is serviced by the ABC Western Queensland radio station.

History

Indigenous

Aboriginal society traded objects based on need and to promote social cohesion. The South West region of Queensland was the primary source of the traded plant Duboisia hopwoodii,[2] from which a traditional chewing tobacco was made.

Kamilaroi (also known as Gamilaroi, Gamilaraay, Comilroy) is an Australian Aboriginal language of South-West Queensland. It is closely related to Yuwaalaraay and Yuwaalayaay. The Kamilaroi language region includes the local government area of the Shire of Balonne, including the towns of Dirranbandi, Thallon, Talwood and Bungunya as well as the border towns of Mungindi and Boomi extending to Moree, Tamworth and Coonabarabran in New South Wales.[3]

Yuwaalaraay (also known as Yuwalyai, Euahlayi, Yuwaaliyaay, Gamilaraay, Kamilaroi, Yuwaaliyaayi) is an Australian Aboriginal language spoken on Yuwaalaraay country. The Yuwaalaraay language region includes the landscape within the local government boundaries of the Shire of Balonne, including the town of Dirranbandi as well as the border town of Hebel extending to Walgett and Collarenebri in New South Wales.[4]

Yuwaalayaay (also known as Yuwalyai, Euahlayi, Yuwaaliyaay, Gamilaraay, Kamilaroi, Yuwaaliyaayi) is an Australian Aboriginal language spoken on Yuwaalayaay country. It is closely related to the Gamilaraay and Yuwaalaraay languages. The Yuwaalayaay language region includes the landscape within the local government boundaries of the Shire of Balonne, including the town of Dirranbandi as well as the border town of Goodooga extending to Walgett and the Narran Lakes in New South Wales.[5]

European

Eastern parts of the region around the upper reaches of the Warrego River were explored by Thomas Mitchell in 1845.[6] It wasn't until after William Landsborough explored the area during his 1862 expedition that settlers began to take up pastoral runs.[6]

In 1860, Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills began an expedition from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria to explore large areas of inland Australia which remained completely unknown to the European settlers. A pivotal meeting place or depôt camp used by the expedition was located at Bullah Bullah Waterhole on Cooper Creek. After failing to reach the northern coastline due to the mangrove swamps of the Flinders River delta the party of four set off for the return journey short on supplies. Charles Gray died on the way leaving three of the party who eventually managed to return to Cooper Creek on 21 April 1861, only to find the other half of the party had just left for Menindee nine hours earlier. A tree at the camp was used to depict three blazes and mark the location of a food cache.[7] It also became the resting place for Burke who died of malnourishment after they ran low on supplies amid controversial and tragic circumstances. Wills also died from weakness and malnourishment downstream at Breerily Waterhole. John King was the sole survivor of the party that trekked north to the gulf. The expedition's journals and maps inspired pastoralists and opened up of vast tracts of Queensland to pastoral settlement.[8]

Western parts of the region receive an average of 150 mm annual rainfall.[9] Further east around St. George, receives an average of 500 mm per year.[9] Limited access to water in the region restricted early pastoralism.[10] After artesian bore water had been discovered and developed the lands were able to support sheep and not just cattle.[10]

A Cobb & Co factory and was built at Charleville in 1893.[9] During the 1880s coach services expanded into the region. Cobb & Co was Australia's most famous historical coaching firm and once provided passenger and mail services across the country. They produced an eight-passenger coach that gained repute for its strength, stability and the forgiving suspension.[11]

In 1922, QANTAS began its first regular flights from Charleville.[9]

Geography

The northern extent of the Sturt Stony Desert lies within the region around the location known as Cameron Corner. Part of the Cooper Basin is located in the region. The basin contains the most significant on-shore petroleum and natural gas deposits in Australia.[12] Near Roma at Hospital Hill, Australia's first natural gas strike was made.[9] Oil was found in the region in 1961.[13] The Eromanga Basin, also located in South West Queensland has been explored and developed for petroleum production.[14] Commercial quantities of gas were first discovered in 1976 and oil in 1978. The Tookoonooka crater is a large impact crater located in the region, however it is not visible at the surface.

Settlements

Major towns of South West Queensland include Charleville, Roma, Augathella, Windorah, Thargomindah, St George and Cunnamulla. Cunnamulla has the biggest wool-loading station on the Queensland railway network.[9] Australia's largest cotton farm, Cubbie Station near St George, covers 93,000 hectares.[15]

Smaller towns in the region include Amby, Injune, Jackson, Mitchell, Muckadilla, Mungallala, Surat, Wallumbilla, Yuleba, Alton, Bollon, Boolba, Dirranbandi, Hebel, Mungindi, Nindigully, Thallon, Coongoola, Eulo, Humeburn, Tuen, Wyandra, Yowah, Bakers Bend, Morven, Nive, Sommariva, Thargomindah, Hungerford, Noccundra, Nockatunga, Norley, Oontoo, Quilpie, Adavale, Cheepie, Eromanga and Toompine. Cooladdi is a ghost town with a population of just six.[16]

Springs

Historical geographical records have suggested changes in the flow of local tertiary sandstone springs have occurred since the 1880s. Blasting was often used to enhance spring flow and consequently causing its destruction as with bores and dams. Only 45% of springs that were historically documented in the south west queensland records, remain.[17]

Rivers

Waterways coursing through South West Queensland include the Warrego, Maranoa, Merivale, Balonne and its tributary the Bokhara River, Culgoa, Wilson and Cooper Creek. The Balonne is used for an extensive irrigation network.[9] The Bulloo River system is the only closed river system in Australia.[18]

Protected areas

A number of national parks have been declared in the region, including Alton National Park, Chesterton Range National Park, Culgoa Floodplain National Park, Currawinya National Park, Diamantina National Park, Idalia National Park, Lake Bindegolly National Park, Mariala National Park, Thrushton National Park and Tregole National Park. Bowra Sanctuary is a nature reserve near Cunnamulla which is managed by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy.

Transport

Major roads in the region include the Mitchell Highway out of outback New South Wales and the Balonne Highway which travels east from St George to Cunnamulla. The Warrego Highway travels in an east/west direction across the north of the region. The northern tip of the Castlereagh Highway passes through the south east of the region, terminating at St George. Also passing through St George is the Carnarvon Highway and the Diamantina Development Road is slowly being upgraded.

The regions is serviced by seven airports, including Dirranbandi Airport, Roma Airport, St George Airport, Charleville Airport, Thargomindah Airport, Cunnamulla Airport and Quilpie Airport. The Western railway line reached Charleville in 1888.[19] A branch line to Cunnamulla was opened in 1898.[19] Today, The Westlander passenger train service operates between Brisbane and Charleville. The South Western railway line passes through Thallon in the south east corner of the region.

Environment

Bioregions in the area include the Mulga Lands. Mulga is a shrub or small tree native to arid outback Australia which has developed extensive adaptations to the dry conditions. There is an isolated population of rufous-crowned emu-wren living in spinifex shrubland which is found in the region. The Dingo Fence runs through the region and is the world's longest fence.[20]

The region is covered by red, brown and grey clays. Red sands and earths predominate, which is typical of arid Australia.[21]

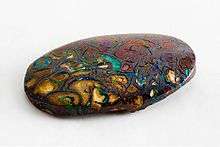

Opals

Adavale was the location of Australia's first opal discovery.[9] The town of Yowah is built on an opal field which began producing opals in the 1870s.[22] Opals are also found at Koroit opal field, Quilpie, Eulo and in northern New South Wales. The geological formation containing opals in South West Queensland is called the Winton Formation.[23]

See also

References

- "National Regional Profile: South West". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- William Howell, Edwards (1988). An Introduction to Aboriginal societies (2 ed.). Cengage Learning Australia. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-876633-89-9. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

-

-

-

- "Cunnamulla". Queensland Places. Centre for the Government of Queensland. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Burke and Wills Dig Tree (entry 601073)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "The Burke and Wills Expedition: Tragedy and Triumph". State Library of Queensland Publications. Department of Public Works. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Agriculture - Statistics - South West". Australian Natural Resources Atlas. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. 25 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Stokes, Chris J.; Ryan R. McAllister; Andrew J. Ash; John E. Gross (2008). "Changing Patterns of Land Use and Tenure in Dalrymple Shire, Australia". In Galvin, Kathleen A.; Ellis, Jim; Reid, Robin S.; Behnke, Roy H.; Thompson Hobbs, N. (eds.). Fragmentation in Semi-Arid and Arid Landscapes: consequences for human and natural systems. Springer. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4020-4905-7. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "H3875 Horsedrawn vehicle, Cobb & Co mail and passenger coach, timber / metal / leather, made by Cobb & Co Coach and Buggy Factory, Charleville, Queensland, Australia, 1890". Powerhouse Museum Collection. NSW Government. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "Petroleum Geology of South Australia Volume 4 - Cooper Basin". Government of South Australia. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Castles, Ian (1990). Year Book of Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. p. 10. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- "Eromanga Basin - Geological Overview". NSW Department of Primary Industries. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Fidelis Rego (18 December 2009). "Offers made for Cubbie Station cotton farm". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Cooladdi". Murweh Shire Council. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Silcock, J. L.; Macdermott, H; Laffineur, B; Fensham, R. J. (2016). "Obscure oases: natural, cultural and historical geography of western Queensland's Tertiary sandstone springs". Geographical Research. 54 (2): 187–202. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12175.

- Char Speedy, "The Bulloo River System: life along the Bullo River 1880-1920s", Watson, Ferguson and Co ISBN 0-646-42858-6

- Environmental Protection Agency (Queensland) (2002). Heritage Trails of the Queensland Outback. State of Queensland. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7345-1040-2.

- "Dingo". New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage. 15 April 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Perry, R.A.; David W. Goodall (1979). Arid land ecosystems: structure, functioning, and management, Volume 1. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-521-21842-9. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Small town gem festival draws masses". ABC Western Queensland. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 18 July 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Opal". Mining and Safety. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.