Punjab

Punjab (Gurmukhi: ਪੰਜਾਬ; Shahmukhi: پنجاب; /pʌnˈdʒɑːb/ (![]()

Punjab | |

|---|---|

Region | |

_with_cities.png) Location of Punjab in South Asia | |

| Countries | |

| Areas | See below |

| Demonym(s) | Punjabi |

| Time zones | UTC+05:30 (IST (India)) |

| UTC+05:00 (PKT (Pakistan)) | |

| Language(s) | Punjabi and its dialects |

| Part of a series on the |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

|

|

Asia

Europe North America Oceania |

|

Culture |

|

Punjab portal |

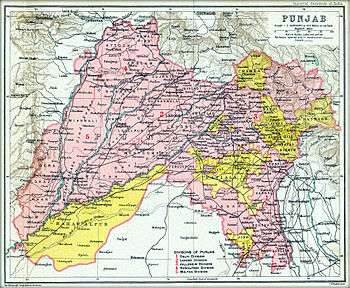

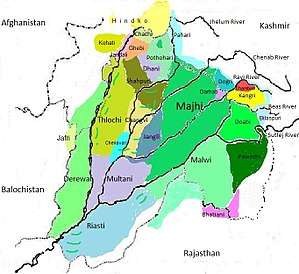

The geographical definition of the term "Punjab" has changed over time. In the 16th century Mughal Empire it referred to a relatively smaller area between the Indus and the Sutlej rivers.[2] In British India, until the Partition of India in 1947, the Punjab Province encompassed the present-day Indian states and union territories of Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh and Delhi and the Pakistani regions of Punjab and Islamabad Capital Territory. It bordered the Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa regions to the west, Kashmir to the north, the Hindi Belt to the east, and Rajasthan and Sindh to the south.

The people of the Punjab today are called Punjabis, and their principal language is Punjabi. The main religion of the Pakistani Punjab region is Islam. The two main religions of the Indian Punjab region are Sikhism and Hinduism. Other religious groups are Christianity, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, and Ravidassia. The Punjab region was the cradle for the Indus Valley Civilisation. The region had numerous migration by the Indo-Aryan peoples. The land was later contested by the Persians, Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians, Kushans, Macedonians, Ghaznavids, Turkic, Mongols, Timurids, Mughals, Marathas, Arabs, Pashtuns, British and other peoples. Historic foreign invasions mainly targeted the most productive central region of the Punjab known as the Majha region,[3] which is also the bedrock of Punjabi culture and traditions.[4] The Punjab region is often referred to as the breadbasket in both India and Pakistan.[5][6][7]

Etymology

The region was originally called Sapta Sindhu,[8] the Vedic land of the seven rivers flowing into the ocean.[9] The origin of the word Punjab can probably be traced to the Sanskrit panca-nada ([pɐntʃɐnɐd̪ɐ]), which literally means 'five rivers', and is used as the name of a region in Mahabharata.[10][11] The later name for the region, Punjab, was introduced to the region by the Turko-Persian conquerors of India,[12] and more formally popularised during the Mughal Empire.[13][14]

Punjab (Persian: پنجآب) is a compound of two Persian words: panj (پنج, 'five'; [pændʒ]) and âb (آب, 'water'; [ɒːb]).[1][15] The word Punjab thus means 'The Land of Five Waters', referring to the rivers Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas.[16] All are tributaries of the Indus River, the Sutlej being the largest.

The ancient Greeks referred to the region as Pentapotamía (Greek: Πενταποταμία),[17][18][19] which has the same etymology as the original Persian word.

Political geography

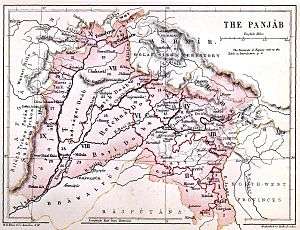

16th century

In the 16th century, during the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar, the term Punjab was synonymous with the Lahore province. It covered a relatively smaller area lying between the Indus and the Sutlej rivers.[2]

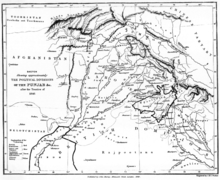

19th century

The 19th century definition of the Punjab region focuses on the collapse of the Sikh Empire and the creation of the British Punjab province between 1846 and 1849. According to this definition, the Punjab region incorporates, in today's Pakistan, Azad Kashmir including Bhimber and Mirpur[20] and parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (especially Peshawar,[21] known in the Punjab region as Pishore).[22] In India, the wider definition includes parts of Delhi and Jammu Division.[23][24][25]

Using the older definition, the Punjab region covers a large territory and can be divided into five natural areas:[1]

- the eastern mountainous region including Jammu Division and Azad Kashmir;

- the trans-Indus region including Peshawar;

- the central plain with its five rivers;

- the north-western region, separated from the central plain by the Salt Range between the Jhelum and the Indus rivers;

- the semi-desert to the south of the Sutlej river.

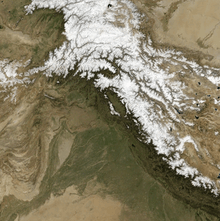

The formation of the Himalayan Range of mountains to the east and north-east of the Punjab is the result of a collision between the north-moving Indo-Australian Plate and the Eurasian Plate. The plates are still moving together, and the Himalayas are rising by about 5 millimetres (0.2 in) per year.

The upper regions are snow-covered the whole year. Lower ranges of hills run parallel to the mountains. The Lower Himalayan Range runs from north of Rawalpindi through Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and further south. The mountains are relatively young, and are eroding rapidly. The Indus and the five rivers of the Punjab have their sources in the mountain range and carry loam, minerals and silt down to the rich alluvial plains, which consequently are very fertile.[26]

Major cities

According to the older definition, some of the major cities include Jammu, Peshawar and parts of Delhi.

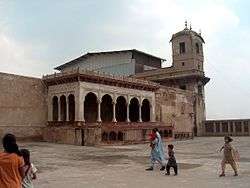

Bahu Fort, Jammu, India

Bahu Fort, Jammu, India- Peshawar Museum

Jama Masjid, Delhi

Jama Masjid, Delhi City view, Mirpur

City view, Mirpur

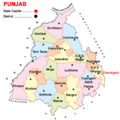

1947 partition

The 1947 definition defines the Punjab region with reference to the dissolution of British India, whereby the then British Punjab Province was partitioned between what would become India and Pakistan. In Pakistan, the region now includes the Punjab province and Islamabad Capital Territory. In India, it includes the Punjab state, Chandigarh, Haryana,[27] and Himachal Pradesh.

Using the 1947 definition, the Punjab borders the Balochistan and Pashtunistan regions to the west, Kashmir to the north, the Hindi Belt to the east, and Rajasthan and Sindh to the south. Accordingly, the Punjab region is very diverse and stretches from the hills of the Kangra Valley to the plains and to the Cholistan Desert.

Present-day maps

- Punjab, Pakistan

Punjab, India, 2014

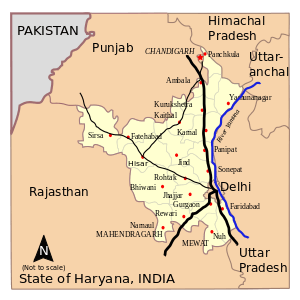

Punjab, India, 2014 Haryana, India

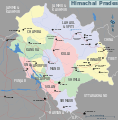

Haryana, India Himachal Pradesh, India

Himachal Pradesh, India

Major cities

Using the 1947 definition of the Punjab region, some of the major cities of the area include Lahore, Faisalabad, Ludhiana and Amritsar.

.jpg) Badshahi Mosque, Lahore

Badshahi Mosque, Lahore Golden Temple, Amritsar

Golden Temple, Amritsar Clock Tower, Faisalabad

Clock Tower, Faisalabad Aerial view of Multan Ghanta Ghar chawk

Aerial view of Multan Ghanta Ghar chawk Open Hand monument, Chandigarh

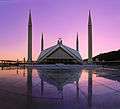

Open Hand monument, Chandigarh Faisal Masjid (Margalla Hills)

Faisal Masjid (Margalla Hills)

Greater Punjab

Another definition of the Punjab region adds to the definitions cited above and includes parts of Rajasthan on linguistic lines and takes into consideration the location of the Punjab rivers in ancient times.[28][29][30][31] In particular, the Sri Ganganagar and Hanumangarh districts are included in the Punjab region.[32]

Anupgarh fort in Anupgarh city

Anupgarh fort in Anupgarh city Bhatner fort in Hanumangarh city

Bhatner fort in Hanumangarh city

Climate

The climate is a factor contributing to the economy of the Punjab. It is not uniform over the whole region, with the sections adjacent to the Himalayas receiving heavier rainfall than those at a distance.[33]

There are three main seasons and two transitional periods. During the hot season from mid-April to the end of June, the temperature may reach 49 °C (120 °F). The monsoon season, from July to September, is a period of heavy rainfall, providing water for crops in addition to the supply from canals and irrigation systems. The transitional period after the monsoon is cool and mild, leading to the winter season, when the temperature in January falls to 5 °C (41 °F) at night and 12 °C (54 °F) by day. During the transitional period from winter to the hot season, sudden hailstorms and heavy showers may occur, causing damage to crops.[34]

History

The Punjab region of India and Pakistan has a historical and cultural link to Indo-Aryan peoples as well as partially to various indigenous communities. As a result of several invasions from Central Asia and the Middle East, many ethnic groups and religions make up the cultural heritage of the Punjab.

In prehistoric times, one of the earliest known cultures of South Asia, the Indus Valley Civilisation was located in the region.

Classical period

The epic battles described in the Mahabharata are described as being fought in what is now the State of Haryana and historic Punjab. The Gandharas, Kambojas, Trigartas, Andhra, Pauravas, Bahlikas (Bactrian settlers of the Punjab), Yaudheyas, and others sided with the Kauravas in the great battle fought at Kurukshetra.[35] According to Dr Fauja Singh and Dr. L. M. Joshi: "There is no doubt that the Kambojas, Daradas, Kaikayas, Andhra, Pauravas, Yaudheyas, Malavas, Saindhavas and Kurus had jointly contributed to the heroic tradition and composite culture of ancient Punjab."[36]

In 326 BCE, Alexander the Great invaded Pauravas and defeated King Porus. His armies entered the region via the Hindu Kush in northwest Pakistan and his rule extended up to the city of Sagala (present-day Sialkot in northeast Pakistan). In 305 BCE the area was ruled by the Maurya Empire. In a long line of succeeding rulers of the area, Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka stand out as the most renowned. The Maurya presence in the area was then consolidated in the Indo-Greek Kingdom in 180 BCE.

Menander I Soter ("Menander I the Saviour"; known as Milinda in Indian sources) is the most renowned leader of the era, he conquered the Punjab and made Sagala the capital of his Empire.[37] Menander carved out a Greek kingdom in the Punjab and ruled the region till his death in 130 BCE.[38] The neighbouring Seleucid Empire rule came to an end around 12 BCE, after several invasions by the Yuezhi and the Scythian people.

Early medieval period (600s to 1206)

In 711–713 CE, the 18-year-old Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim of Taif, a city in what is now Saudi Arabia, came by way of the Arabian Sea with Arab troops to defeat Raja Dahir. Bin Qasim conquered parts of present day Sindh and southern Punjab for the Umayyad Caliphate. The newly created state of Sind, encompassing part of the Punjab, brought Islamic rule to the region for the first time. Sind would later be governed by the Abbasid Caliphate, before fragmenting into five smaller kingdoms, one of which was based in Multan. The remainder of the Punjab at this time was governed by the Hindu Shahis and local Rajputs.

In 1001, Mahmud of Ghazni began a series of raids which culminated in establishing Ghaznavid rule across the Punjab by 1026. The Ghaznavids, a Persianate Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin,[39][lower-alpha 2][40] reigned until 1186 when they were defeated and replaced by the Ghurid dynasty of Iranian descent from the Ghor region of present-day central Afghanistan.[41]

Late medieval period (1206-1526)

Following the death of Muhammad of Ghor in 1206 the Ghurid state fragmented and in northern India was replaced by the Delhi Sultanate. The Delhi Sultanate ruled the Punjab for the next three hundred years, led by five unrelated dynasties, the Mamluks, Khalajis, Tughlaqs, Sayyids and Lodis.

Early modern period (1526-1858)

In 1526, the Delhi Sultanate was conquered and succeeded by the Turko-Mongol Mughal Empire. Under the Mughals prosperity, growth, and relative peace were established, particularly under the reign of Jahangir. The period was also notable for the emergence of Guru Nanak (1469–1539), the founder of Sikhism.

The Afghan forces of Durrani Empire (also known as the Afghan Empire), under the command of Ahmad Shah Durrani, entered Punjab in 1749, and captured Punjab—with Lahore being governed by Pashtuns—and Kashmir regions. In 1758, Punjab came under the rule of Marathas, who captured the region by defeating the Afghan forces of Ahmad Shah Abdali. Following Third Battle of Panipat against Marathas, Durranis reconsolidated its power and dominion over the Punjab region, and Kashmir Valley. Abdali's Indian invasion weakened the Maratha influence.

After the death of Ahmad Shah, the Punjab was freed from the Afghan rule by Sikhs for a brief period between 1773 and 1818. At the time of the formation of the Dal Khalsa in 1748 at Amritsar, the Punjab had been divided into 36 areas and 12 separate Sikh principalities, called Misl. From this point onward, the beginnings of a Punjabi Sikh Empire emerged. Out of the 36 areas, 22 were united by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The other 14 accepted East India Company sovereignty. After Ranjit Singh's death, assassinations and internal divisions severely weakened the empire. Six years later, the British East India Company was given an excuse to declare war, and in 1849, after two Anglo-Sikh wars, the Punjab was annexed by the East India Company. In the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Sikh rulers backed the East India Company, providing troops and support.[42] However, in Jhelum, 35 British soldiers of HM XXIV regiment were killed by the local resistance, and in Ludhiana, a rebellion was crushed with the assistance of the Punjab chiefs of Nabha and Malerkotla.

Modern period (after 1858)

The British Raj had political, cultural, philosophical, and literary consequences in the Punjab, including the establishment of a new system of education. During the independence movement, many Punjabis played a significant role, including Madan Lal Dhingra, Sukhdev Thapar, Ajit Singh Sandhu, Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh, Kartar Singh Sarabha, Bhai Parmanand, Choudhry Rahmat Ali, and Lala Lajpat Rai. At the time of partition in 1947, the province was split into East and West Punjab. East Punjab (48%) became part of India, while West Punjab (52%) became part of Pakistan.[43] The Punjab bore the brunt of the civil unrest following the end of the British Raj, with casualties estimated to be in the millions.

Timeline

- 3300–1500 BCE: Indus Valley Civilisation

- 1500–1000 BCE: (Rigvedic) Vedic civilisation

- 1000–500 BCE: Middle and late Vedic Period

- 599 BCE: Birth of Mahavira

- 567–487 BCE: Time of Gautama Buddha

- 550 BCE – 600 CE: Buddhism remained prevalent

- 326 BCE: Alexander's Invasion of Punjab

- 322–298 BCE: Chandragupta I, Maurya period

- 273–232 BCE: Reign of Ashoka

- 125–160 BCE: Rise of the Sakas (Scythians)

- 2 BCE: Beginning of Rule of the Sakas

- 45–180: Rule of the Kushans

- 320–550: Gupta Empire

- 500: Hunnic Invasion

- 510–650: Vardhana's Era

- 711–713: Muhammad bin Qasim conquers Sindh and small part of Punjab region

- 713–1200: Rajput states, Kabul Shahi & small Muslim kingdoms

- 1206–1290: Mamluk dynasty established by Mohammad Ghori

- 1290–1320: Khalji dynasty established by Jalal ud din Firuz Khalji

- 1320–1413: Tughlaq dynasty established by Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq

- 1414–1451: Sayyid dynasty established by Khizr Khan

- 1451–1526: Lodhi dynasty established by Bahlul Khan Lodhi

- 1469–1539: Guru Nanak

- 1526–1707: Mughal rule

- 1526–1530: Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babur

- 1530–1540: Nasiruddin Muhammad Humayun

- 1540–1545: Sher Shah Suri of Afghanistan

- 1545–1554: Islam Shah Suri

- 1555–1556: Nasiruddin Muhammad Humayun

- 1556–1556: Hem Chandra Vikramaditya

- 1556–1605: Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar

- 1605–1627: Nooruddin Muhammad Jahangir

- 1627–1658: Shahaabuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan

- 1658–1707: Mohiuddin Muhammad Aurangzeb Alamgir

- 1539–1675: Period of 8 Sikh Gurus from Guru Angad Dev to Guru Tegh Bahadur

- 1675–1708: Guru Gobind Singh (10th Sikh Guru)

- 1699: Birth of the Khalsa

- 1708–1713: Conquests of Banda Bahadur

- 1714–1759: Sikh chiefs (Sardars) war against Afghans & Mughal Governors

- 1722: Birth of Ahmed Shah Durrani, either in Multan in Mughal Empire or Herat in Afghanistan

- 1739: Invasion by Nader Shah and defeat of weakened Mughal Empire

- 1747–1772: Durrani Empire led by Ahmad Shah Durrani

- 1756–1759: Sikh and Maratha Empire cooperation in the Punjab

- 1761: The Third Battle of Panipat, between the Durrani Empire against the Maratha Empire.

- 1762: 2nd massacre (Ghalughara) from Ahmed Shah's 2nd invasion

- 1765–1801: Rise of the Sikh Misls, who gained control of significant swathes of Punjab

- 1801–1839: Sikh Empire also known as Sarkar Khalsa, Rule by Maharaja Ranjit Singh

- 1845–1846: First Anglo-Sikh War

- 1846: Jammu joined with the new state of Jammu and Kashmir

- 1848–1849: Second Anglo-Sikh War

- 1849: Complete annexation of Punjab into British India

- 1849–1947: British rule

- 1901: Peshawar and adjoining districts separated from the Punjab Province

- 1911: Parts of Delhi separated from Punjab Province

- 1947: The Partition of India divided Punjab into two parts: the Eastern side, with two rivers, became the Indian Punjab; and the Western side, with three rivers, became the Pakistan Punjab.

- 1966: Indian Punjab divided into three parts: Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh

- 1973–1995: Punjab insurgency

Culture and people

Languages

The major language is Punjabi, (Gurmukhi: ਪੰਜਾਬੀ; Shahmukhi: پنجابی) written in India with the Gurmukhi script, and in Pakistan using the Shahmukhi script.[44] It has official status and is widely used in education and administration in Indian Punjab, whereas in Pakistani Punjab these roles are instead played by Urdu. In the western half of the Pakistani province, the major native languages are Saraiki, Hindko and Pothwari, all of which are closely related to Punjabi.

Religions

The vast majority of Pakistani Punjabis are Sunni Muslim by faith, but also include large minority faiths mostly Shia Muslim, Ahmadis, and Christians.

Sikhism, founded by Guru Nanak is the main religion practised in the post-1966 Indian Punjab state. About 57.7% of the population of Punjab state is Sikh, 38.5% is Hindu, and the rest are Muslims, Christians, and Jains.[45] Punjab state contains the holy Sikh cities of Amritsar, Anandpur Sahib, Tarn Taran Sahib, Fatehgarh Sahib and Chamkaur Sahib.

The Punjab was home to several Sufi saints, and Sufism is well established in the region.[46] Also, Kirpal Singh revered the Sikh Gurus as saints.[47]

| Religious group |

Population % 1881 |

Population % 1891 |

Population % 1901 |

Population % 1911 |

Population % 1921 |

Population % 1931 |

Population % 1941 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam | 47.6% | 47.8% | 49.6% | 51.1% | 51.1% | 52.4% | 53.2% |

| Hinduism | 43.8% | 43.6% | 41.3% | 35.8% | 35.1% | 30.2% | 29.1% |

| Sikhism | 8.2% | 8.2% | 8.6% | 12.1% | 12.4% | 14.3% | 14.9% |

| Christianity | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Other religions / No religion | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

Religion in Punjab Region (2011)[49]

Festivals

Punjabis celebrate different festivals based on their following culture, season and religion:

- Maghi

- Lohri

- Maha Shivratri

- Holi

- Vaisakhi

- Teeyan

- Raksha Bandhan

- Diwali

- Gurpurab

- Hola Mohalla

- Mela Chiraghan

- Bandi Chhor Divas

- Dussehra

- Karwa Chauth

- Navratri

- Basant

Islam

Others

Clothing

Traditional Punjabi clothing differs depending on the region. It includes the following:

Economy

The historical region of Punjab is considered to be one of the most fertile regions on Earth. Both east and west Punjab produce a relatively high proportion of India and Pakistan's food output respectively. The region has been used for extensive wheat farming. In addition, rice, cotton, sugarcane, fruit, and vegetables are also grown.

The agricultural output of the Punjab region in Pakistan contributes significantly to Pakistan's GDP. Both Indian and Pakistani Punjab are considered to have the best infrastructure of their respective countries. Indian Punjab has been estimated to be the second richest state in India.[50] Pakistani Punjab produces 68% of Pakistan's food grain production.[51] Its share of Pakistan's GDP has historically ranged from 51.8% to 54.7%.[52]

Called "The Granary of India" or "The Bread Basket of India," Indian Punjab produces 1% of the world's rice, 2% of its wheat, and 2% of its cotton.[53] In 2001, it was recorded that farmers made up 39% of Indian Punjab's workforce.

Alternatively, Punjab is also adding to the economy with the increase in employment of Punjab youth in the private sector. Government schemes such as 'Ghar Ghar Rozgar and Karobar Mission' have brought enhanced employability in the private sector. So far, 32,420 youths have been placed in different jobs and 12,114 have been skill-trained.[54]

See also

Notes

References

- H K Manmohan Siṅgh. "The Punjab". The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Editor-in-Chief Harbans Singh. Punjabi University, Patiala. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- J. S. Grewal (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India (Revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0.

- Jatiinder Aulakh. Archaeological History of Majha: Research Book about Archaeology and Mythology with Rare Photograph. Createspace Independent Pub, 2014

- Arrain, Anabasis, V.22, p.115

- "Punjab, bread basket of India, hungers for change". Reuters. 30 January 2012.

- "Columbia Water Center Released New Whitepaper: "Restoring Groundwater in Punjab, India's Breadbasket" – Columbia Water Center". Water.columbia.edu. 7 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- "Pakistan flood: Sindh braces as water envelops southern Punjab". Guardian. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Bhandarkar, D. R. 1989. Some Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture: Sir WIlliam Meyers Lectures, 1938–39. New Delhi: Asia Educational Services. ISBN 8120604571. p. 2.

- Valdiya, A. S. 2013. "River Sarasvati was a Himalayn-born river." Current Science 104(1):42–54. ISSN 0011-3891.

- Kenneth Pletcher, ed. (2010). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4.

The word's origin can perhaps be traced to panca nada, Sanskrit for “five rivers” and the name of a region mentioned in the ancient epic the Mahabharata.

- Rajesh Bala (2005). "Foreign Invasions and their Effect on Punjab". In Sukhdial Singh (ed.). Punjab History Conference, Thirty-seventh Session, March 18-20, 2005: Proceedings. Punjabi University. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-7380-990-3.

The word Punjab is a compound of two words-Panj (Five) and aab (Water), thus signifying the land of five waters or rivers. This origin can perhaps be traced to panch nada, Sanskrit for 'Five rivers' the word used before the advent of Muslims with a knowledge of Persian to describe the meeting point of the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers, before they joined the Indus.

- Canfield, Robert L. (1991). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 1 ("Origins"). ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- Shimmel, Annemarie (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. London, United Kingdom: Reaktion Books Ltd. ISBN 1-86189-1857.

- Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 1 ("Introduction"). ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- "Punjab." Pp. 107 in Encyclopædia Britannica (9th ed.), vol. 20.

- Lassen, Christian. 1827. Commentatio Geographica atque Historica de Pentapotamia Indica [A Geographical and Historical Commentary on Indian Pentapotamia]. Weber. p. 4: "That part of India which today we call by the Persian name ''Penjab'' is named Panchanada in the sacred language of the Indians; either of which names may be rendered in Greek by Πενταποταμια. The Persian origin of the former name is not at all in doubt, although the words of which it is composed are both Indian and Persian.… But, in truth, that final word is never, to my knowledge, used by the Indians in proper names compounded in this way; on the other hand, there exist multiple Persian names which end with that word, e.g., Doab and Nilab. Therefore it is probable that the name Penjab, which is today found in all geographical books, is of more recent origin and is to be attributed to the Muslim kings of India, among whom the Persian language was mostly in use. That the Indian name Panchanada is ancient and genuine is evident from the fact that it is already seen in the Ramayana and Mahabharata, the most ancient Indian poems, and that no other exists in addition to it among the Indians; for Panchála, which English translations of the Ramayana render with Penjab…is the name of another region, entirely distinct from Pentapotamia…."

- Latif, Syad Muhammad (1891). History of the Panjáb from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. Calcultta Central Press Company. p. 1.

The Panjáb, the Pentapotamia of the Greek historians, the north-western region of the empire of Hindostán, derives its name from two Persian words, panj (five), an áb (water, having reference to the five rivers which confer on the country its distinguishing features."

- Khalid, Kanwal (2015). "Lahore of Pre Historic Era" (PDF). Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan. 52 (2): 73.

The earliest mention of five rivers in the collective sense was found in Yajurveda and a word Panchananda was used, which is a Sanskrit word to describe a land where five rivers meet. [...] In the later period the word Pentapotamia was used by the Greeks to identify this land. (Penta means 5 and potamia, water ___ the land of five rivers) Muslim Historians implied the word "Punjab " for this region. Again it was not a new word because in Persian speaking areas, there are references of this name given to any particular place where five rivers or lakes meet.

- Hutchison, Vogel. 1933. History of Panjab Hill States. "Mirpur was made a part of Jammu and Kashmir in 1846."

- Khan, Mohammad Asif. 2007. Changes in the Socio-economic Structures in Rural North-West Pakistan. p. 15. Archived 14 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Peshawar was separated from Punjab Province in 1901.

- Nadiem, Ihsan H. (2007). Peshawar: heritage, history, monuments. Sang-e-Meel Publications. ISBN 9789693519716. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- "Jammu and Kashmir". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- "Epilogue, Vol 4, Issue 11". Archived from the original on 4 February 2016.

- Pritam Singh Gill (1978). History of Sikh nation: foundation, assassination, resurrection. University of Michigan: New Academic Pub. Co. p. 380.

- G. S. Gosal. "Physical Geography of the Punjab" (PDF). University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- Darpan, Pratiyogita (1 October 2009). "Pratiyogita Darpan". Pratiyogita Darpan. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- The Times Atlas of the World, Concise Edition. London: Times Books. 1995. p. 36. ISBN 0-7230-0718-7.

- Grewal, J S (2004). Historical Geography of the Punjab (PDF). Punjab Research Group, Volume 11, No 1. Journal of Punjab Studies. pp. 4, 7, 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2012.

- see the Punjab Doabs

- Pritam Singh and Shinder S. Thandi, ed. (1996). Globalisation and the region: explorations in Punjabi identity. Coventry Association for Punjab Studies, Coventry University. p. 361.

- Balder Raj Nayat (1966). Minority Politics in the Punjab. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Maps of India, Climate of Punjab Archived 30 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Royal Geographical Society Climate and Landscape of the Punjab Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Buddha Parkash, Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab, p 36.

- Joshi, L. M., and Fauja Singh. History of Panjab, Vol I. p. 4.

- Hazel, John (2013). Who's Who in the Greek World. Routledge. p. 155. ISBN 9781134802241.

Menander king in India, known locally as Milinda, born at a village named Kalasi near Alasanda (Alexandria-in-the-Caucasus), and who was himself the son of a king. After conquering the Punjab, where he made Sagala his capital, he made an expedition across northern India and visited Patna, the capital of the Mauraya empire, though he did not succeed in conquering this land as he appears to have been overtaken by wars on the north-west frontier with Eucratides.

- Ahir, D. C. (1971). Buddhism in the Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh. Maha Bodhi Society of India. p. 31. OCLC 1288206.

Demetrius died in 166 B.C., and Apollodotus, who was a near relation of the King died in 161 B.C. After his death, Menander carved out a kingdom in the Punjab. Thus from 161 B.C. onward Menander was the ruler of Punjab till his death in 145 B.C. or 130 B.C.

- Levi & Sela 2010, p. 83.

- Bosworth 1963, p. 4.

- C. E. Bosworth: GHURIDS. In Encyclopaedia Iranica. 2001 (last updated in 2012). Online edition.

- Ganda Singh (August 2004). "The Truth about the Indian Mutiny". Sikh Spectrum. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "Pakistan Geotagging: Partition of Punjab in 1947". 3 October 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.. Daily Times (10 May 2012). Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- https://www.omniglot.com/writing/punjabi.htm

- "Census Reference Tables, C-Series Population by religious communities". Census of India. 2001. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- "Sufi Saints of the Punjab". Punjabics.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Kirpal Singh, Sant. "The Punjab – Home of Master Saints". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Gopal Krishan. "Demography of the Punjab (1849–1947)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- "Punjab second richest state in country: CII", The Times of India, 8 April 2004.

- Pakistani government statistics Archived 8 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973–2000 Indian Super League

- Yadav, Kiran (11 February 2013). "Punjab". Agropedia. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- DelhiOctober 7, Press Trust of India New; October 7, 2019UPDATED; Ist, 2019 10:03. "Punjab govt to identify poorest among unemployed in villages: Amarinder Singh". India Today. Retrieved 7 October 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Narang, K.S.; Gupta, Dr H.R. (1969). History of the Punjab 1500–1858 (PDF). U. C. Kapur & Sons, Delhi. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- [Quraishee 73] Punjabi Adab De Kahani, Abdul Hafeez Quaraihee, Azeez Book Depot, Lahore, 1973.

- [Chopra 77] Punjab as a Sovereign State, Gulshan Lal Chopra, Al-Biruni, Lahore, 1977.

- Patwant Singh. 1999. The Sikhs. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50206-0.

- The Evolution of Heroic Tradition in Ancient Panjab, 1971, Buddha Parkash.

- Social and Political Movements in ancient Panjab, Delhi, 1962, Buddha Parkash.

- History of Porus, Patiala, Buddha Parkash.

- History of the Panjab, Patiala, 1976, Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi (Ed).

- The Legacy of the Punjab, 1997, R. M. Chopra.

- The Rise Growth and Decline of Indo-Persian Literature, R. M. Chopra, 2012, Iran Culture House, New Delhi. 2nd revised edition, published in 2013.

- Sims, Holly. "The State and Agricultural Productivity: Continuity versus Change in the Indian and Pakistani Punjabs." Asian Survey, 1 April 1986, Vol. 26(4), pp. 483–500.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Punjab region. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Punjab. |