Donbass

The Donbass or Donbas (UK: /dɒnˈbɑːs/,[1] US: /ˈdɒnbɑːs, dʌnˈbæs/;[2][3] Ukrainian: Донба́с [donˈbɑs];[4] Russian: Донба́сс) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine and southwestern Russia.[4][5] The word Donbass is a portmanteau formed from Donets Basin (Ukrainian: Донецький басейн, romanized: Donets'kyj basejn; Russian: Донецкий бассейн, romanized: Donetskij bassejn), in reference to the river Donets that flows through it.[6] Multiple definitions of the region's extent exist, and its boundaries have never been officially demarcated.[7]

The most common definition in use today refers to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine, whilst the historical coal mining region excluded parts of these oblasts, and included areas in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast and Southern Russia.[8] A Euroregion of the same name is composed of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in Ukraine and Rostov Oblast in Russia.[9] Donbass formed the historical border between the Zaporizhian Sich and the Don Cossack Host. It has been an important coal mining area since the late 19th century, when it became a heavily industrialised territory.[10]

In March 2014, following the Euromaidan and 2014 Ukrainian revolution, large swaths of the Donbass became gripped by unrest. This unrest later grew into a war between pro-Russian separatists affiliated with the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics (neither of which are recognized as legitimate by any of the UN member states[11]), and the post-revolutionary Ukrainian government. Until the ongoing war, the Donbass was the most densely populated of all the regions of Ukraine apart from the capital city of Kiev.

Before the war, the city of Donetsk (then the fifth largest city of Ukraine) had been considered the unofficial capital of the Donbass. Large cities (over 100,000 inhabitants) also included Luhansk, Mariupol, Makiivka, Horlivka, Kramatorsk, Sloviansk, Alchevsk, Sievierodonetsk and Lysychansk. Now the city of Kramatorsk is the interim administrative center of the Donetsk Oblast, whereas the interim center of Luhansk Oblast is the city of Severodonetsk. On the separatist side, Donetsk, Makiivka and Horlivka are now the largest cities in the Donetsk People's Republic, and Luhansk and Alchevsk in the Luhansk People's Republic.

History

_eng.png)

The region has been inhabited for centuries by various Iranian and Turkic nomadic tribes such as Scythians, Bulgars, Pechenegs, Kipchaks, Turco-Mongols, Tatars and Nogais. The region now known as the Donbass was largely unpopulated until the second half of the 17th century, when Don Cossacks established the first permanent settlements in the region.[12] The first town in the region was founded in 1676, called Solanoye (now Soledar), which was built for the profitable business of exploiting newly discovered rock-salt reserves. Known for being "Wild Fields" (Ukrainian: дике поле, dyke pole), the area that is now called the Donbass was largely under control of the Ukrainian Cossack Hetmanate and the Turkic Crimean Khanate until the mid-late 18th century, when the Russian Empire conquered the Hetmanate and annexed the Khanate.[13] At the end of the 18th century many Ukrainians, Russians, Serbs and Greeks migrated to the region.[14] Tsarist Russia named the conquered territories "New Russia" (Russian: Новоро́ссия, Novorossiya). As the Industrial Revolution took hold across Europe, the vast coal resources of the region, discovered in 1721, began to be exploited in the mid-late 19th century.[15] It was at this point that the name "Donbass" came into use, derived from the term "Donets Coal Basin" (Ukrainian: Донецький вугільний басейн; Russian: Донецкий каменноугольный бассейн), referring the area along the river Donets where most of the coal reserves were found. The rise of the coal industry led to a population boom in the region, largely driven by Russian settlers.[16] The region was governed as the Bakhmut, Slovianserbsk and Mariupol counties of Yekaterinoslav Governorate.

Donetsk, the most important city in the region today, was founded in 1869 by British businessman John Hughes on the site of the old Zaporozhian Cossack town of Oleksandrivka. Hughes built a steel mill and established several collieries in the region. The city was named after him as "Yuzovka" (Russian: Юзовка). With development of Yuzovka and similar cities, large amounts of landless peasants from peripheral governorates of the Russian Empire came looking for work.[6]

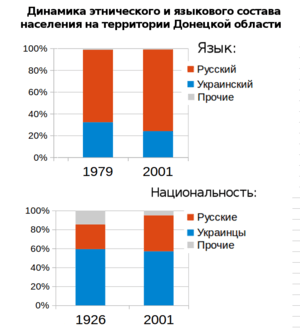

According to the Russian Imperial Census of 1897, ethnic Ukrainians comprised 52.4% of the population of region, whilst ethnic Russians comprised 28.7%.[17] Ethnic Greeks, Germans, Jews and Tatars also had a significant presence in the Donbass, particularly in the district of Mariupol, where they comprised 36.7% of the population.[18] Despite this, Russians constituted the majority of the industrial work-force. Ukrainians dominated rural areas, but cities were often inhabited solely by Russians who had come seeking work in the region's heavy industries.[19] Those ethnic Ukrainians who did move to the cities for work were quickly assimilated into the Russian-speaking worker class.[20]

Into the Soviet period

In April 1918 troops loyal to the Ukrainian People's Republic took control of large parts of the region.[21] For a while, its government bodies operated in the Donbass alongside their Russian Provisional Government equivalents.[22] The Ukrainian State, the successor of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was able in May 1918 to bring the region under control for a short time with the help of its German and Austro-Hungarian allies.[22]

In the 1917–22 Russian Civil War Nestor Makhno, who had power and more or less consistently fulfilled his promises, was the most popular leader in the Donbass.[22]

Along with other territories inhabited by Ukrainians, the Donbass was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the aftermath of the Russian Civil War. Cossacks in the region were subjected to decossackisation during 1919–1921.[23] Ukrainians in the Donbass were greatly affected by the 1932–33 Holodomor famine and the Russification policy of Joseph Stalin. As most ethnic Ukrainians were rural peasant farmers (called "kulaks" by the Soviet regime), they bore the brunt of the famine.[24][25] According to the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain, the population of the area that is now Luhansk Oblast declined by 25% as a result of the famine, whereas it declined by 15–20% in the area that is now Donetsk Oblast.[26] According to one estimate, 81.3% of those who died during the famine in the Ukrainian SSR were ethnic Ukrainians, whilst only 4.5% were ethnic Russians.[27]

Donbass was greatly affected by the Second World War. In the lead up to the war, the Donbass was racked by poverty and food shortages. War preparations resulted in an extension of the working day for factory labourers, whilst those that deviated from the heightened standards were arrested.[28] German Reich leader Adolf Hitler viewed the resources of the Donbass as critical to Operation Barbarossa. As such, the Donbass suffered under Nazi occupation during 1941 and 1942.[29] Thousands of industrial laborers were forcibly "exported" to Germany for use in factories. In what was then called Stalino Oblast, now Donetsk Oblast, 279,000 civilians were killed over the course of the occupation. In Voroshilovgrad Oblast, now Luhansk Oblast, 45,649 were killed.[30] An offensive by the Red Army in 1943 resulted in the return of Donbass to Soviet control. The war had taken its toll, leaving the region both destroyed and depopulated.

During the reconstruction of the Donbass after World War II, large numbers of Russian workers arrived to repopulate the region, further altering the population balance. In 1926, 639,000 ethnic Russians resided in the Donbass.[31] By 1959, the ethnic Russian population was 2.55 million. Russification was further advanced by the 1958–59 Soviet educational reforms, which led to the near elimination of all Ukrainian-language schooling in the Donbass.[32][33] By the time of the Soviet Census of 1989, 45% of the population of the Donbass reported their ethnicity as Russian.[34]

In independent Ukraine

In the 1991 referendum on Ukrainian independence, 83.9% of voters in Donetsk Oblast and 83.6% in Luhansk Oblast supported independence from the Soviet Union. Turnout was 76.7% in Donetsk Oblast and 80.7% in Luhansk Oblast.[35] In October 1991 a congress of South-Eastern deputies from all levels of government took place in Donetsk, where delegates demanded federalisation.[22]

The region's economy deteriorated severely in the ensuing years. By 1993, industrial production had collapsed, and average wages had fallen by 80% since 1990. Donbass fell into crisis, with many accusing the new central government in Kiev of mismanagement and neglect. Donbass coal miners went on strike in 1993, causing a conflict that was described by historian Lewis Siegelbaum as "a struggle between the Donbass region and the rest of the country". One strike leader said that Donbass people had voted for independence because they wanted "power to be given to the localities, enterprises, cities", not because they wanted heavily centralised power moved from "Moscow to Kiev".[35]

This strike was followed by a 1994 consultative referendum on various constitutional questions in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, held concurrently with the first parliamentary elections in independent Ukraine.[36] These questions included whether Russian should be enshrined as an official language of Ukraine, whether Russian should be the language of administration in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, whether Ukraine should federalise, and whether Ukraine should have closer ties with the Commonwealth of Independent States.[37] Close to 90% of voters voted in favour of these propositions.[38] None of them were adopted: Ukraine remained a unitary state, Ukrainian was retained as the sole official language, and the Donbass gained no autonomy.[34] Nevertheless, the Donbass strikers gained many economic concessions from Kiev, allowing for an alleviation of the economic crisis in the region.[35]

Small strikes continued throughout the 1990s, though demands for autonomy faded. Some subsidies to Donbass heavy industries were eliminated, and many mines were closed by the Ukrainian government because of liberalising reforms pushed for by the World Bank.[35] Ukrainian president Leonid Kuchma, who won the 1994 presidential election with support from the Donbass and other areas in eastern Ukraine, was re-elected in 1999.[35] Kuchma gave economic aid to the Donbass, using development money to gain political support in the region.[35] Power in the Donbass became concentrated in a regional political elite, known as oligarchs, during the early 2000s. Privatisation of state industries led to rampant corruption. Regional historian Hiroaki Kuromiya described this elite as the "Donbass clan", a group of people that controlled economic and political power in the region.[35] Prominent members of the "clan" included Viktor Yanukovych and Rinat Akhmetov. The formation of the oligarchy, combined with corruption, led to perceptions of the Donbass as "the least democratic and the most sinister region in Ukraine".[35]

In other parts of Ukraine during the 2000s, Donbass was often perceived as having a "thug culture", as being a "Soviet cesspool", and as "backward". Writing in the Narodne slovo newspaper in 2005, commentator Viktor Tkachenko said that Donbass was home to "fifth columns", and that speaking Ukrainian in the region was "not safe for one's health and life".[39] It was also portrayed as being home to pro-Russian separatism. Donbass is home to a significantly higher number of cities and villages that were named after Communist figures compared to the rest of Ukraine.[40] Despite this portrayal, surveys taken across that decade and during the 1990s showed strong support for remaining within Ukraine, and insignificant support for separatism.[41]

War in Donbass (2014–present)

.jpg)

From the beginning of March 2014, demonstrations by pro-Russian and anti-government groups took place in the Donbass, as part of the aftermath of the February 2014 Ukrainian revolution and the Euromaidan movement. These demonstrations, which followed the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, and which were part of a wider group of concurrent pro-Russian protests across southern and eastern Ukraine, escalated in April 2014 into a war between the separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics (DPR and LPR respectively), and the Ukrainian government.[42][43]

Amidst the ongoing war, the separatist republics held referendums on the status of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts on 11 May 2014. In the referendums, viewed as illegal by Ukraine and undemocratic by the international community, about 90% voted for the independence of the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic.[44] (Although the Russian word used, самостоятельность, (samostoyatel'nost) (literally "standing by oneself"), can be translated as either full independence or broad autonomy, which left voters confused about what their ballot actually meant.[45][44]) Fighting continued through 2014, and into 2015, despite several attempts at implementing a ceasefire. Ukraine said Russia provided both material and military support to the separatists, though it denied this.[46][47] The separatists were largely led by Russian citizens until August 2014.[46][47]

On January 11, 2017, the Cabinet of Ministers in Ukraine approved a plan for the reintegration of the region and population of Donbass.[48] The plan would give Russia partial control of the electorate and has been described by Zerkalo Nedeli as "implanting a cancerous cell into Ukraine’s body."[49]

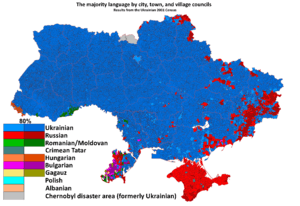

Demographics and politics

According to the 2001 census, ethnic Ukrainians form 58% of the population of Luhansk Oblast and 56.9% of Donetsk Oblast. Ethnic Russians form the largest minority, accounting for 39% and 38.2% of the two oblasts respectively.[50] Modern Donbass is a predominately Russophone region. According to the 2001 census, Russian is the main language of 74.9% of residents in Donetsk Oblast and 68.8% in Luhansk Oblast.[51] The proportion of native Russian-speakers is higher than ethnic Russians because some ethnic Ukrainians and other nationalities also indicate Russian as their mother tongue.

Residents of Russian origin are mainly concentrated in the larger urban centers. Russian became the main language and lingua franca in the course of industrialization, boosted by the immigration of many Russians, particularly from Kursk Oblast, to newly founded cities in Donbas. A subject of continuing research controversies, and often denied in these two oblasts, is the extent of forced emigration and deaths during the Soviet period, which particularly affected rural Ukrainians during the Holodomor which resulted as a consequence of early Soviet industrialization policies combined with two years of drought throughout southern Ukraine and the Volga region.[52][53]

Nearly all Jews, unless they fled (and sizable numbers of Donbass Jews did, in fact, flee in 1941), were wiped out during the German occupation in World War II. Donbass is about 6% Muslim according to the official censuses of 1926 and 2001.

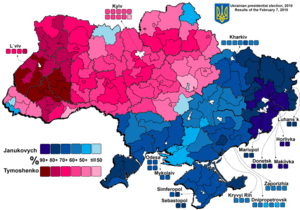

Prior to the Ukrainian crisis in 2013–14, the politics of the region were dominated by the pro-Russian Party of Regions, which gained about 50% of Donbass votes in the 2008 Ukrainian parliamentary election. Prominent members of that party, such as former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, were from the Donbass.

According to linguist George Shevelov, in the early 1920s the proportion of secondary schools teaching in the Ukrainian language was lower than the proportion of ethnic Ukrainians in Donbass[54] – even though the Soviet Union had ordered that all schools in the Ukrainian SSR should be Ukrainian-speaking (as part of its Ukrainization policy).[55]

Surveys of regional identities in Ukraine have shown that around 40% of Donbass residents claim to have a "Soviet identity".[56] Roman Horbyk of Södertörn University wrote that in the 20th century, "[a]s peasants from all surrounding regions were flooding its then busy mines and plants on the border of ethnically Ukrainian and Russian territories", "incomplete and archaic institutions" prevented Donbass residents from "acquiring a notably strong modern urban – and also national – new identity".[54]

Religion

Religion in Donbass (2016)[57]

According to a 2016 survey of religion in Ukraine held by the Razumkov Center, 65.0% of the population in Donbass believe in Christianity (including 50.6% Orthodox, 11.9% who declared to be "simply Christians", and 2.5% who belonged to Protestant churches). Islam is the religion of 6% of the population of Donbass and Hinduism of the 0.6%, both the religions with a share of the population that is higher compared to other regions of Ukraine. People who declared to be not believers or believers in some other religions, not identifying in one of those listed, were 28.3% of the population.[57]

Economy

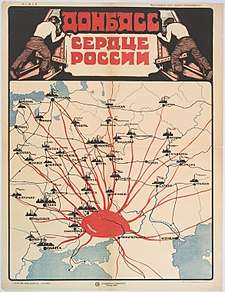

Donbass is dominated by heavy industry, such as coal mining and metallurgy. The region takes its name from an abbreviation of the term "Donets Coal Basin" (Ukrainian: Донецький вугільний басейн, Russian: Донецкий угольный бассейн), and while annual extraction of coal has decreased since the 1970s, Donbass remains significant supplier. Donbass represents one of the largest coal reserves in Ukraine having estimated reserves of 60 billion tonnes of coal.[58] Coal mining in Donbass is conducted at very deep depths. Lignite mining takes place at around 600 metres (2,000 ft) below the surface, whilst mining for more valuable anthracite and bituminous coal takes place at depths of around 1,800 metres (5,900 ft).[15] Prior to the start of the region's war in April 2014, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts together produced about 30 percent of Ukraine's exports.[59] Other industries in Donetsk which may overlap Donbass include blast-furnace and steel-making equipment, railway freight cars, metal-cutting machine-tools, tunneling machines, agricultural harvesters and ploughing systems, railway tracks, mining cars, electric locomotives, military vehicles, tractors and excavators. The region also produces consumer goods like household washing-machines, refrigerators, freezers, TV sets, leather footwear, and toilet soap. Over half its production is exported, and about 22% is exported to Russia.[60]

In mid-March 2017, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a decree on a temporary ban on the movement of goods to and from territory controlled by the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic meaning that since then Ukraine does not buy coal from the Donets Coal Basin.[61]

Occupational safety in the coal industry

The coal mines of Donbass are some of the most hazardous in the world because of the deep depths of mines, as well as frequent methane explosions, coal dust explosions, rock burst dangers, and outdated infrastructure.[62] Even more hazardous illegal coal mines became very common across the region in the late 2000s.[10][63]

Environmental problems

Intensive coal mining and smelting in Donbass have led to severe damage to the local environment. The most common problems throughout the region include:

- water supply disruption and flooding due to the mine water

- visible air pollution around coke and steel mills

- air/water contamination and mudslide threat from spoil tips

Additionally, several chemical waste disposal sites in the Donbass have not been maintained, and pose a constant threat to the environment. One unusual threat is the result of the Soviet-era 1979 project to test experimental nuclear mining in Yenakiieve. For example, on September 16, 1979, at the Yunkom Mine, known today as the Young Communard mine in Yenakiyeve, a 300kt nuclear test explosion was conducted at 900m to free methane gas or to degasified coal seams into a sandstone oval dome known as the Klivazh [Rift] Site so that methane would not pose a hazard or threat to life.[64] Before Glasnost, no miners were informed of the presence of radioactivity at the mine, however.[64]

See also

- Donbass Arena

- Donetsk People's Republic

- HC Donbass, an ice hockey team based in Donetsk bearing the name of the region

- Kryvbas, an important economic region in central Ukraine

- Luhansk People's Republic

- Ruhr, a comparable region in Germany

- Russians in Ukraine

- War in Donbass

References

- "Donbas". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Donbas". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Donetsk Basin". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Donets Basin – region, Europe". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- "Settlement patterns – Russia". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Olga Klinova. ""Если вместо головы снаряд...". Як формувалась ідентичність Донбасу (If instead of head, there is a gunshell. How the Donbas identity was formed)". Ukrayinska Pravda (Istorychna Pravda). 11 December 2014

- Донбасс – единственная часть Украины, возникшая из промышленного региона (in Russian)

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0521526086.

- "Euroregion Donbass". Association of European Border Regions. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- "The coal-mining racket threatening Ukraine's economy". BBC News. 23 April 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- "Ukraine's rebel 'people's republics' begin work of building new states". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Donets Basin" (Donbas), pp.135–136 in: Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Ivan Katchanovski, Zenon E. Kohutuk, Bohdan Y. Nebesio, Myroslav Yurkevich. Lanham : The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2013. 914 p. ISBN 081087847X

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 0521526086.

- Yekelchyk, Serhy (2015). The Conflict in Ukraine: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0190237301.

- The Editors of The Encyclopædia Britannica (2014). "Donets Basin". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (2): 274. JSTOR 261051.

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0521526086.

- "The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 − Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia". Institute of Demography at the National Research University 'Higher School of Economics'. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Lewis H. Siegelbaum; Daniel J. Walkowitz (1995). Workers of the Donbass Speak: Survival and Identity in the New Ukraine, 1982–1992. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-7914-2485-5.

- Stephen Rapawy (1997). Ethnic Reidentification in Ukraine (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- (in Ukrainian) 100 years ago Bakhmut and the rest of Donbass liberated, Ukrayinska Pravda (18 April 2018)

- Lessons for the Donbas from two wars, The Ukrainian Week (16 January 2019)

- "Soviet order to exterminate Cossacks is unearthed". University of York. University of York. 19 November 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

'Ten thousand Cossacks were slaughtered systematically in a few weeks in January 1919 [...] 'And while that wasn't a huge number in terms of what happened throughout the Russia, it was one of the main factors which led to the disappearance of the Cossacks as a nation. [...]'

- Potocki, Robert (2003). Polityka państwa polskiego wobec zagadnienia ukraińskiego w latach 1930–1939 (in Polish and English). Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej. ISBN 978-8-391-76154-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. pp. 208–209. ISBN 0-7656-0665-8.

- "The Number of Dead". Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Sergei Maksudov, "Losses Suffered by the Population of the USSR 1918–1958", in The Samizdat Register II, ed. R. Medvedev (London–New York 1981)

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–255. ISBN 0521526086.

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 0521526086.

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0521526086.

- Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (2): 275. JSTOR 261051.

- L.A. Grenoble (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 1402012985.

- Bohdan Krawchenko (1985). Social change and national consciousness in twentieth-century Ukraine. Macmillan. ISBN 0333361997.

- Don Harrison Doyle, ed. (2010). Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements. University of Georgia Press. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0820330082.

- Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008). Europe's Last Frontier?. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-0-230-60372-1.

- Kataryna Wolczuk (2001). The Moulding of Ukraine. Central European University Press. pp. 129–188. ISBN 9789639241251.

- Hryhorii Nemyria (1999). Regional Identity and Interests: The Case of East Ukraine. Between Russia and the West: Foreign and Security Policy of Independent Ukraine. Studies in Contemporary History and Security Policy.

- Bohdan Lupiy. "Ukraine And European Security – International Mechanisms As Non-Military Options For National Security of Ukraine". Individual Democratic Institutions Research Fellowships 1994–1996. North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008). Europe's Last Frontier?. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-230-60372-1.

- (in Ukrainian) In Ukraine rename 22 cities and 44 villages, Ukrayinska Pravda (4 June 2015)

- Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008). Europe's Last Frontier?. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 108–111. ISBN 978-0-230-60372-1.

- Grytsenko, Oksana (12 April 2014). "Armed pro-Russian insurgents in Luhansk say they are ready for police raid". Kyiv Post.

- Leonard, Peter (14 April 2014). "Ukraine to deploy troops to quash pro-Russian insurgency in the east". Yahoo News Canada. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Wiener-Bronner, Daniel (11 May 2014). "Referendum on Self-Rule in Ukraine 'Passes' with Over 90% of the Vote". The Wire. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

"Ukraine denounces pro-Russian referendums". The Globe and Mail. 11 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014. - East Ukraine goes to the polls for independence referendum | The Observer. The Guardian. 10 May 2014.

- "Pushing locals aside, Russians take top rebel posts in east Ukraine". Reuters. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- Strelkov/Girkin Demoted, Transnistrian Siloviki Strengthened in 'Donetsk People's Republic', Vladimir Socor, Jamestown Foundation, 15 August 2014

- "Government's plan for the reintegration of Donbas: the pros, cons and alternatives | UACRISIS.ORG". [:en]Ukraine crisis media center[:ua]Український кризовий медіа-центр[:fr]Ukraine crisis media center[:de]Ukrainisches Krisen-Medienzentrum[:ru]Украинский кризисный медиа-центр[:es]Ukraine crisis media center[:it]Ukraine crisis media center[:pt]Ukraine crisis media center[:]. 24 January 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "Ukraine's leaders may be giving up on reuniting the country". The Economist. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- "About number and composition population of UKRAINE by data All-Ukrainian population census 2001 data". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011.

- "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 – English version – Results – General results of the census –& Linguistic composition of the population". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua.

- "Ukrainian 'Holodomor' (man-made famine) Facts and History". www.holodomorct.org. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "The Cause and the Consequences of Famines in Soviet Ukraine". faminegenocide.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Games from the Past: The continuity and change of the identity dynamic in Donbass from a historical perspective , Södertörn University (19 May 2014)

- Language Policy in the Soviet Union by Lenore Grenoble, Springer Science+Business Media, 2003, ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3 (page 84)

- Soviet conspiracy theories and political culture in Ukraine:Understanding Viktor Yanukovych and the Party of Region Archived 16 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Taras Kuzio (23 August 2011)

- РЕЛІГІЯ, ЦЕРКВА, СУСПІЛЬСТВО І ДЕРЖАВА: ДВА РОКИ ПІСЛЯ МАЙДАНУ (Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan) Archived 22 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 2016 report by Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches. pp. 27–29.

- "Coal in Ukraine" (PDF). edu.ua. 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Oliver Schmidtke, ed. (2008). Europe's Last Frontier?. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-230-60372-1.

- "Donets'k Region – Regions of Ukraine – MFA of Ukraine". mfa.gov.ua.

- Ukrainian energy industry: thorny road of reform, UNIAN (10 January 2018)

- Grumau, S. (2002). Coal mining in Ukraine. Economic Review.44.

- Panova, Kateryna (8 July 2011). "Illegal mines profitable, but at massive cost to nation". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Kazanskyi, Denys (16 April 2018), "Disaster in the making: The "DPR government" has announced its intention to flood the closed Young Communard mine in Yenakiyeve. 40 years ago, nuclear tests were carried out in it, and nobody knows today what the consequences would be if groundwater erodes the radioactive rock", The Ukrainian Week, retrieved 5 October 2018

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Donbass. |