Andaman and Nicobar Islands

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a Union territory of India comprising 572 islands of which 37 are inhabited, are a group of islands at the juncture of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea.[5]

Andaman and Nicobar Islands | |

|---|---|

(clockwise from top) Barren Island, Beach at Ross and Smith island; Sunset at Andaman Island; Diving in Andamans | |

Seal | |

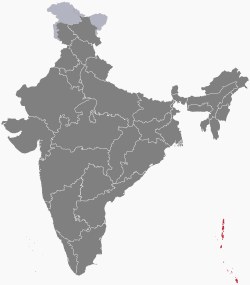

Location of Andaman and Nicobar Islands in India | |

| Coordinates (Port Blair): 11.68°N 92.77°E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1 November 1956 |

| Capital and largest city | Port Blair |

| Districts | 3 |

| Government | |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Admiral (ret.) Devendra Kumar Joshi |

| • Chief Secretary | Chetan Bhushan Sanghi, IAS |

| • Lok Sabha constituencies | 1 |

| • High Court | Calcutta High Court - Port Blair Bench |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,250 km2 (3,190 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 28th |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Total | 380,520 |

| • Density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Languages[3] | |

| • Official | Hindi, English[3] |

| • Spoken | Bengali, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Nicobarese, Kurukh, Munda, Kharia[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-AN |

| HDI (2018) | |

| Website | www |

| Symbols | |

| Mammal | Dugong – 2004 |

| Bird | Andaman Wood Pigeon – 2004 |

| Flower | Pyinma – 2014 |

| Tree | Andaman Padauk – 2004 |

The territory is about 150 km (93 mi) north of Aceh in Indonesia and separated from Thailand and Myanmar by the Andaman Sea. It comprises two island groups, the Andaman Islands (partly) and the Nicobar Islands, separated by the 150 km wide Ten Degree Channel (on the 10°N parallel), with the Andamans to the north of this latitude, and the Nicobars to the south (or by 179 km). The Andaman Sea lies to the east and the Bay of Bengal to the west.

The territory's capital is the city of Port Blair. The total land area of the islands is approximately 8,249 km2 (3,185 sq mi). The territory is divided into three districts: Nicobar District with Car Nicobar as capital, South Andaman district with Port Blair as capital and North and Middle Andaman district with Mayabunder as capital.

The islands host the Andaman and Nicobar Command, the only tri-service geographical command of the Indian Armed Forces.

The Andaman Islands are home to the Sentinelese people, an uncontacted people. The Sentinelese might be the only people currently known to not have reached further than a Paleolithic level of technology,[6] however, this is disputed, as evidence of metalwork was found in their island.[7]

History

First inhabitants

The earliest archaeological evidence documents some 2,200 years. However, genetic and cultural studies suggest that the indigenous Andamanese people may have been isolated from other populations during the Middle Paleolithic, which ended 30,000 years ago.[8] Since that time, the Andamanese have diversified into linguistically and culturally distinct, territorial groups.

The Nicobar Islands appear to have been populated by people of various backgrounds. By the time of European contact, the indigenous inhabitants had coalesced into the Nicobarese people, speaking a Mon-Khmer language, and the Shompen, whose language is of uncertain affiliation. Neither language is related to Andamanese.

Chola empire period

Rajendra Chola I (1014 to 1042 AD), used the Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a strategic naval base to launch an expedition against the Sriwijaya Empire (modern-day Indonesia). The Cholas called the island Ma-Nakkavaram ("great open/naked land"), found in the Thanjavur inscription of 1050 AD. European traveller Marco Polo (12th–13th century) also referred to this island as 'Necuverann' and a corrupted form of the Tamil name Nakkavaram would have led to the modern name Nicobar during the British colonial period.[9]

Danish colonial period and British rule

.jpg)

The history of organised European colonisation on the islands began when settlers from the Danish East India Company arrived in the Nicobar Islands on 12 December 1755. On 1 January 1756, the Nicobar Islands were made a Danish colony, first named New Denmark, and later (December 1756) Frederick's Islands (Frederiksøerne). During 1754–1756 they were administrated from Tranquebar (in continental Danish India). The islands were repeatedly abandoned due to outbreaks of malaria between 14 April 1759 and 19 August 1768, from 1787 to 1807/05, 1814 to 1831, 1830 to 1834 and gradually from 1848 for good.

From 1 June 1778 to 1784, Austria mistakenly assumed that Denmark had abandoned its claims to the Nicobar Islands and attempted to establish a colony on them,[10] renaming them Theresia Islands.

In 1789 the British set up a naval base and penal colony on Chatham Island next to Great Andaman, where now lies the town of Port Blair. Two years later the colony was moved to Port Cornwallis on Great Andaman, but it was abandoned in 1796 due to disease.

Denmark's presence in the territory ended formally on 16 October 1868 when it sold the rights to the Nicobar Islands to Britain,[10] which made them part of British India in 1869.

In 1858 the British again established a colony at Port Blair, which proved to be more permanent. The primary purpose was to set up a penal colony for criminal convicts from the Indian subcontinent. The colony came to include the infamous Cellular Jail.

In 1872 the Andaman and Nicobar islands were united under a single chief commissioner at Port Blair.

World War II

During World War II, the islands were practically under Japanese control, only nominally under the authority of the Arzi Hukumate Azad Hind of Subhash Chandra Bose. Bose visited the islands during the war and renamed them as "Shaheed-Dweep" (Martyr Island) and "Swaraj-dweep" (Self-rule Island).

General Loganathan, of the Indian National Army, was made the Governor of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. On 22 February 1944 he along with four INA officers—Major Mansoor Ali Alvi, Sub. Lt. Md. Iqbal, Lt. Suba Singh, and stenographer Srinivasan—arrived at Lambaline Airport in Port Blair. On 21 March 1944, the Headquarters of the Civil Administration was established near the gurdwara at Aberdeen Bazaar. On 2 October 1944, Col. Loganathan handed over the charge to Maj. Alvi and left Port Blair, never to return.[11]

Japanese Vice Admiral Hara Teizo and Major-General Tamenori Sato surrendered the islands to Brigadier J A Salomons, commander of 116th Indian Infantry Brigade, and Chief Administrator Noel K Patterson, Indian Civil Service, on 7 October 1945, in a ceremony performed on the Gymkhana Ground, Port Blair.

After independence

During the independence of both India (1947) and Burma (1948), the departing British announced their intention to resettle all Anglo-Indians and Anglo-Burmese on these islands to form their own nation, although this never materialised. It became part of India in 1950 and was declared as a union territory of the nation in 1956.[12]

India has been developing defence facilities on the islands since the 1980s. The islands now have a key position in India's strategic role in the Bay of Bengal and the Malacca Strait.[13]

2004 tsunami

On 26 December 2004, the coasts of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands were devastated by a 10 m (33 ft) massive tsunami following the undersea earthquake off Indian Ocean. More than 2,000 people lost their lives, more than 4,000 children were orphaned or suffered the loss of one parent, and a minimum of 40,000 people were rendered homeless. More than 46,000 people were injured.[14] The worst affected Nicobar islands were Katchal and Indira Point; the latter subsided 4.25 metres (13.9 feet) and was partially submerged in the ocean. The lighthouse at Indira Point was damaged but has been repaired since then. The territory lost a large amount of area which is now submerged. The territory which was at Indian states 8,073 km2 (3,117 sq mi) is now at 7,950 km2 (3,070 sq mi).[15]

While locals and tourists of the islands suffered the greatest casualties from the tsunami, most of the aboriginal people survived because oral traditions passed down from generations ago warned them to evacuate from large waves that follow large earthquakes.[16]

Geography

There are 572 islands[17] in the territory having an area of 8,249 km2 (3,185 sq mi). Of these, about 38 are permanently inhabited. The islands extend from 6° to 14° North latitudes and from 92° to 94° East longitudes. The Andamans are separated from the Nicobar group by a channel (the Ten Degree Channel) some 150 km (93 mi) wide. The highest point is located in North Andaman Island (Saddle Peak at 732 m (2,402 ft)). The Andaman group has 325 islands which cover an area of 6,170 km2 (2,382 sq mi) while the Nicobar group has only 247 islands with an area of 1,765 km2 (681 sq mi).[12]:33

The capital of the union territory, Port Blair, is located 1,255 km (780 mi) from Kolkata, 1,200 km (750 mi) from Visakhapatnam and 1,190 km (740 mi) from Chennai.[12]:33 The northernmost point of the Andaman and Nicobars group is 901 km (560 mi) away from the mouth of the Hooghly River and 280 km (170 mi) from Myanmar Mainland. Indira Point at 6°45’10″N and 93°49’36″E at the southern tip of the southernmost island, Great Nicobar, is the southernmost point of India and lies only 200 km (120 mi) from Sumatra island in Indonesia.

The only volcano in India, Barren Island, is located in Andaman and Nicobar. It is an active volcano and had last erupted in 2017. It also has a mud volcano situated in Baratang island, These mud volcanoes have erupted sporadically, with recent eruptions in 2005 believed to have been associated with the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. The previous major eruption recorded was on 18 February 2003. The locals call this mud volcano Jalki. There are other volcanoes in the area. This island's beaches, mangrove creeks, limestone caves, and mud volcanoes are some of the physical features.

In December 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was on a two-day visit to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, renamed three of the islands as a tribute to Subhas Chandra Bose. Ross Island was renamed as Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Island; Neil Island as Shaheed Island; and Havelock Island as Swaraj Island. The PM made this announcement during a speech at the Netaji Stadium, marking the 75th anniversary of the hoisting of the Indian flag by Bose there.[18][19]

The Sisters

The Sisters are two small uninhabited islands, East Sister Island and West Sister Island, in the Andaman Archipelago, at the northern side of the Duncan Passage, about 6 km (3.2 nmi) southeast of Passage Island and 18 km (9.7 nmi) north of North Brother. The islands are about 820.21 feet (250.00 metres) apart, connected by a coral reef; they are covered by forests and have rocky shores except for a beach on the northwest side of East Sister Island.

Before the British established a colony on the Andaman, the Sisters were visited occasionally by the Onge people of Little Andaman Island for fishing. The islands may have been a waystation on the way to their temporary settlement of Rutland Island between 1890 and 1930.

The islands have been designated as a wildlife refuge since 1987, with an area of 0.36 square kilometres (0.14 sq mi).

Flora

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands have a tropical rainforest canopy, made of a mixed flora with elements from Indian, Myanmar, Malaysian and endemic floral strains. So far, about 2,200 varieties of plants have been recorded, out of which 200 are endemic and 1,300 do not occur in mainland India.

The South Andaman forests have a profuse growth of epiphytic vegetation, mostly ferns, and orchids. The Middle Andamans harbours mostly moist deciduous forests. North Andamans is characterised by the wet evergreen type, with plenty of woody climbers. The North Nicobar Islands (including Car Nicobar and Battimalv) are marked by the complete absence of evergreen forests, while such forests form the dominant vegetation in the central and southern islands of the Nicobar group. Grasslands occur only in the Nicobars, and while deciduous forests are common in the Andamans, they are almost absent in the Nicobars. The present forest coverage is claimed to be 86.2% of the total land area.

This atypical forest coverage is made up of twelve types, namely:

- Giant evergreen forest

- Andamans tropical evergreen forest

- Southern hilltop tropical evergreen forest

- Canebrakes

- Wet bamboo brakes

- Andamans semi-evergreen forest

- Andamans moist deciduous forest

- Andamans secondary moist deciduous forest

- Littoral forest

- Mangrove forest

- Brackish water mixed forest

- Submontane forest

Fauna

This tropical rain forest, despite its isolation from adjacent landmasses, is surprisingly rich with a diversity of animal life.

About 50 varieties of forest mammals are found to occur in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Some are endemic, including the Andaman wild boar. Rodents are the largest group with 26 species, followed by 14 species of bat. Among the larger mammals there are two endemic varieties of wild boar, Sus scrofa andamanensis from Andaman and Sus scrofa nicobaricus from Nicobar, which are protected by the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 (Sch I). Saltwater crocodile is also found in abundance. The State Animal of Andaman is the dugong, also known as the sea cow, which can be found in Little Andaman. Around 1962 there was an attempt to introduce the leopard, which was unsuccessful because of unsuitable habitat. These were ill-considered moves as exotic introductions can cause havoc to island flora and fauna. Elephants also can be found in forested or mountainous areas of the islands, they are brought over from the mainland to help with timber extraction in 1883.[20]

About 270 species of birds are found in the territory; 14 of them are endemic, the majority to the Nicobar island group. The islands' many caves are nesting grounds for the edible-nest swiftlet, whose nests are prized in China for bird's nest soup.[21]

The territory is home to about 225 species of butterflies and moths. Ten species are endemic to these Islands. Mount Harriet National Park is one of the richest areas of butterfly and moth diversity on these islands.

The islands are well known for prized shellfish, especially from the genera Turbo, Trochus, Murex and Nautilus. Earliest recorded commercial exploitation began during 1929. Many cottage industries produce a range of decorative shell items. Giant clams, green mussels and oysters support edible shellfishery. The shells of scallops, clams, and cockle are burnt in kilns to produce edible lime.

There are 96 wildlife sanctuaries, nine national parks and one biosphere reserve in these islands.[22]

Demographics

| Population growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1901 | 24,649 | — | |

| 1911 | 26,459 | 7.3% | |

| 1921 | 27,086 | 2.4% | |

| 1931 | 29,463 | 8.8% | |

| 1941 | 33,768 | 14.6% | |

| 1951 | 30,971 | −8.3% | |

| 1961 | 63,548 | 105.2% | |

| 1971 | 115,133 | 81.2% | |

| 1981 | 188,741 | 63.9% | |

| 1991 | 280,661 | 48.7% | |

| 2001 | 356,152 | 26.9% | |

| 2011 | 380,581 | 6.9% | |

| Source:Census of India[23] | |||

As of 2011 Census of India, the population of the Union Territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands was 379,944, of which 202,330 (53.25%) were male and 177,614 (46.75%) were female. The sex ratio was 878 females per 1,000 males.[24] Only 10% of the population lived in Nicobar islands.

The areas and populations (at the 2001 and 2011 Censuses) of the three districts[25] are:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population Census 2001 | Population Census 2011 | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicobar Islands | 1,765 | 42,068 | 36,842 | Car Nicobar |

| North and Middle Andaman | 3,536 | 105,613 | 105,597 | Mayabunder |

| South Andaman | 2,640 | 208,471 | 238,142 | Port Blair |

| Totals | 7,950 | 356,152 | 380,581 |

There remain approximately 400–450 indigenous Andamanese in the Andaman islands, the Jarawa and Sentinelese in particular maintaining steadfast independence and refusing most attempts at contact. In the Nicobar Islands, the indigenous people are the Nicobarese, or Nicobari, living throughout many of the islands, and the Shompen, restricted to the hinterland of Great Nicobar. More than 2,000 people belonging to the Karen tribe live in the Mayabunder tehsil of North Andaman district, almost all of whom are Christians. Despite their tribal origins, the Karen of Andamans have Other Backward Class (OBC) status in the Andamans.

Languages

Bengali is the most spoken language in Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[3] Hindi is the official language of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, while English is declared an additional official language for communication purposes.[6] As of 2011 census, Bengali is spoken as the first language by 28.49 per cent of the Union Territory's population followed by Hindi (19.29%), Tamil (15.20%), Telugu (13.24%), Nicobarese (7.65%) and Malayalam (7.22%).[26]

Religion

The majority of people of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are Hindus (69.45%), with Christians forming a large minority of 21.7% of the population, according to the 2011 census of India. There is a significant Muslim (8.51%) minority.

Administration

In 1874, the British had placed the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in one administrative territory headed by a Chief Commissioner as its judicial administrator. On 1 August 1974, the Nicobar islands were hived off into another revenue district with district headquarters at Car Nicobar under a Deputy Commissioner. In 1982, the post of Lieutenant Governor was created who replaced the Chief Commissioner as the head of administration. Subsequently, a "Pradesh council" with Councillors as representatives of the people was constituted to advise the Lieutenant Governor.[12] The Islands sends one representative to Lok Sabha from its Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Lok Sabha constituency).

Administrative divisions

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands is divided into three districts:

- North and Middle Andaman (Capital: Mayabunder)

- South Andaman (Capital: Port Blair)

- Nicobar (Capital: Car Nicobar)

Each district is further divided into sub-divisions and taluks:

Sub-Divisions and Taluks in North and Middle Andaman District

- Diglipur Sub-Division

- Diglipur taluk

- Mayabunder Sub-Division

- Mayabunder taluk

- Rangat taluk

Sub-Divisions and Taluks in South Andaman District

- Port Blair Sub-Division

- Port Blair taluk

- Ferrargunj taluk

- Jirkatang taluk (native Jarawa reservation)

- Ritchie's Archipelago Sub-Division

- Ritchie's Archipelago taluk (Havelock Island)

- Little Andaman Sub-Division

- Little Andaman taluk (Hut Bay)

Sub-Divisions and Taluks in Nicobar District

- Car Nicobar Sub-Division

- Car Nicobar taluk

- Nancowrie Sub-Division

- Great Nicobar Sub-Division

- Little Nicobar taluk

- Great Nicobar taluk (Campbell Bay)

Economy

Agriculture

A total of 48,675 hectares (120,280 acres) of land is used for agriculture purposes. Paddy, the main food crop, is mostly cultivated in Andaman group of islands, whereas coconut and arecanut are the cash crops of Nicobar group of islands. Field crops, namely pulses, oilseeds and vegetables are grown, followed by paddy during Rabi season. Different kinds of fruits such as mango, sapota, orange, banana, papaya, pineapple and root crops are grown on hilly land owned by farmers. Spices such as pepper, clove, nutmeg, and cinnamon are grown under a multi-tier cropping system. Rubber, red oil, palm, noni and cashew are grown on a limited scale in these islands.

Industry

There are 1,374 registered small-scale, village and handicraft units. Two units are export-oriented in the line of fish processing activity. Apart from this, there are shells and wood-based handicraft units. There are also four medium-sized industrial units. SSI units are engaged in the production of polythene bags, PVC conduit pipes and fittings, paints and varnishes, fiberglass and mini flour mills, soft drinks, and beverages, etc. Small scale and handicraft units are also engaged in shell crafts, bakery products, rice milling, furniture making, etc.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation has spread its wings in the field of tourism, fisheries, industries, and industrial financing and functions as authorised agents for Alliance Air. The Islands have become a tourist destination, due to the draw of their largely unspoiled virgin beaches and waters.[28]

Tourism

Tourism to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands is increasing due to the popularity of beaches and adventure sports like snorkelling and sea-walking.[29] Plans to develop various islands under NITI (National Institute of Transforming India) Aayog is also in progress. Luxury resorts with participation from the Government are set up to plan in Avis Island, Smith Island and Long Island.[30]

In Port Blair, the main places to visit are the Cellular Jail, Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park, Andaman Water sports complex, Chatham Saw Mill, Mini Zoo, Corbyn's cove, Chidiya Tapu, Wandoor Beach, Forest Museum, Anthropological Museum, Fisheries Museum, Naval Museum (Samudrika), Ross Island and North Bay Island. Viper Island which was earlier visited is now kept closed by the administration. Other places include Havelock island famous for Radhanagar Beach, Neil Island for Scuba diving/snorkeling/sea walking, Cinque Island, Saddle peak, Mt Harriet, and Mud Volcano. Diglipur, located at North Andaman is also getting popular in 2018 and many tourists have started visiting North Andaman as well. The southern group (Nicobar islands) is mostly inaccessible to tourists.

Indian tourists do not require a permit to visit the Andaman Islands, but if they wish to visit any tribal areas they need a special permit from the Deputy Commissioner in Port Blair. Permits are required for foreign nationals. For foreign nationals arriving by air, these are granted upon arrival at Port Blair.

According to official estimates, the flow of tourists tripled to nearly 430,000 in 2016-17 from 130,000 in 2008–09. The Radha Nagar beach was chosen as Asia's best beach in 2004.[29]

Gallery

The beauty of the sea and coasts

The beauty of the sea and coasts Andaman Islands

Andaman Islands Seascape at Chidiyatapu, Andaman islands

Seascape at Chidiyatapu, Andaman islands- Andaman and Nicobar islands

This is the coral reef an Havelock in Andaman.

This is the coral reef an Havelock in Andaman.

Macro-economic trend

This is a chart of trend of gross state domestic product (GSDP) of Andaman and Nicobar Islands at market prices, estimated by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, with figures in millions of Indian rupees.[31]

| Year | GSDP (millions of ₹) |

|---|---|

| 1985 | 590 |

| 1990 | 1,100 |

| 1995 | 4,000 |

| 2000 | 7,750 |

| 2005 | 10,560 |

| 2010 | 16,130 |

Andaman and Nicobar Islands' gross state domestic product for 2004 was estimated at $354 million in current prices.

Power generation

With Japanese assistance, Southern Andaman Island will now have a 15-megawatt diesel power plant. This would be the first foreign investment of any kind allowed at this strategically significant island chain. This is believed to be an Indo-Japanese strategic initiative to strengthen civilian infrastructure in the vicinity of the Strait of Malacca – a strategically important choke-point for the Chinese oil supply.[32][33]

Infrastructure

Internet

Internet access on the islands used to be limited and unreliable, since all connectivity to the outside world had to go through satellite links. Bharat Broadband Network started work on laying a fibre optic submarine cable running from the five islands to Chennai on 30 December 2018, with completion expected in December 2019.[34][35] On 10 August 2020, PM Narendra Modi formally inaugurated the Chennai - Andaman undersea Optical fibre cable which enables high-speed broadband connections in the Union Territory. The submarine cable also connects Port Blair to Swaraj Dweep, Little Andaman, Car Nicobar, Kamorta, Great Nicobar, Long Island and Rangat.[36] The initial bandwidth of the cable is 400 Gbit/s, roughly 400 times more than what the islands possessed before the fibre link.[37][38]

Ports

On 10 August 2020, PM Narendra Modi announced plans for the construction of a transshipment port in the Great Nicobar Island at a cost of ₹10,000 crore to provide shippers an alternative to similar ports in the region. The move is aimed at improving the ease of doing business of the country and enhancing maritime logistics.[39]

Popular culture

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle refers to the Andaman Islands in his Sherlock Holmes novel The Sign of the Four.[40]

See also

- 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami

- Effect of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake on India

- Endemic birds of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- 2014 Andaman boat disaster

- Coral reefs in India

Notes

References

- "Andaman and Nicobar Administration". And.nic.in. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Census of India Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 2011. Census Data Online, Population.

- "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). 16 July 2014. p. 109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "www.andaman.gov.in". Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- Sawhney, Pravin (30 January 2019). "A watchtower on the high seas". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Andaman & Nicobar Administration". and.nic.in. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015.

- Pandit, T. N. (1990). The Sentinelese. Kolkata: Seagull Books. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-81-7046-081-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palanichamy, Malliya G.; Agrawal, Suraksha; Yao, Yong-Gang; Kong, Qing-Peng; Sun, Chang; Khan, Faisal; Chaudhuri, Tapas Kumar; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006). "Comment on 'Reconstructing the Origin of Andaman Islanders'". Science. 311 (5760): 470. doi:10.1126/science.1120176. PMID 16439647.

- Government of India (1908). "The Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Local Gazetteer". Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta.

... In the great Tanjore inscription of 1050 AD, the Andamans are mentioned under a translated name along with the Nicobars, as Nakkavaram or land of the naked people.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ramerini, Marco. "Chronology of Danish Colonial Settlements". ColonialVoyage.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2005. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- "Black Days in Andaman and Nicobar Islands" by Rabin Roychowdhury, [Pub. Manas] Pubs. New Delhi

- Planning Commission of India (2008). Andaman and Nicobar Islands Development Report. State Development Report series (illustrated ed.). Academic Foundation. ISBN 978-81-7188-652-4. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- David Brewster. "India's Defence Strategy and the India-ASEAN Relationship. Retrieved on 24 August 2014". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Carl Strand and John Masek, ed. (2007). Sumatra-Andaman Islands Earthquake and Tsunami of December 6, 2004: Lifeline Performance. Reston, VA: ASCE, Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering. ISBN 9780784409510. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013.

- Effect of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake on India

- "Tsunami folklore 'saved islanders'". BBC News. 20 January 2005. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Brief Industrial Profile of Andaman and Nicobar Islands" (PDF). Government of India Ministry of M.S.M.E. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Bedi, Rahul (1 January 2019). "Indian PM strips islands of British colonial names – and renames them after freedom fighter". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "PM Modi renames 3 Andaman & Nicobar islands as tribute to Netaji". The Economic Times. 31 December 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Thomas, Maria (4 August 2016). "The incredible life of India's iconic swimming elephant". qz.com. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- R. Sankaran (1999), The impact of nest collection on the Edible-nest Swiftlet in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Archived 4 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Coimbatore, India.

- India Year Book 2015

- "Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901".

- "Census of India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- source: The Office of Registrar General & Census Commissioner of India

- "DISTRIBUTION OF THE 22 SCHEDULED LANGUAGES-INDIA/STATES/UNION TERRITORIES – 2011 CENSUS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- "Andaman and Nicobar Islands – Unexplored Beauty of India". The Indian Backpacker. December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- "How Andaman & Nicobar can fully capitalize its Tourism Potential?". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Holistic Development of Islands". Niti Aayog. Niti Aayog. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Archived 16 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "India collaborates with Japan on Andamans project". The Hindu. 13 March 2016. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "These 8 narrow chokepoints are critical to the world's oil trade". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "PM Modi inaugurates 2,312-kilometre undersea optical fibre cable link between Andaman-Chennai". The Indian Express. 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Sridhar, Lalitha (17 February 2018). "It's 2018, but still tough to get online in the Andamans". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "Andaman and Nicobar islands' fast-speed internet will depend on a 2,300 kilometre-long fibre optic cable". Business Insider. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "BSNL to enhance bandwidth 400 times in Andaman and Nicobar island in 2 years". Financial Express. 26 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Aug 10, TIMESOFINDIA COM /; 2020; Ist, 10:44. "PM Modi inaugurates Chennai-Andaman & Nicobar submarine optical cable project - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 August 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- www.ETHRWorld.com. "India plans Rs 10,000 cr transshipment port at Great Nicobar Island: PM - ETHRWorld". ETHRWorld.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Hill, David (31 March 2012). "The 'wild' people as tourist stops". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Andaman and Nicobar Islands. |

- Census of India, Provisional Population Totals

- Andaman and Nicobar Administration Website

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands at Curlie