French Polynesia

French Polynesia (/ˈfrɛntʃ pɒlɪˈniːʒə/ (![]()

French Polynesia | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: "La Marseillaise" | |

| Territorial anthem: "Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui" | |

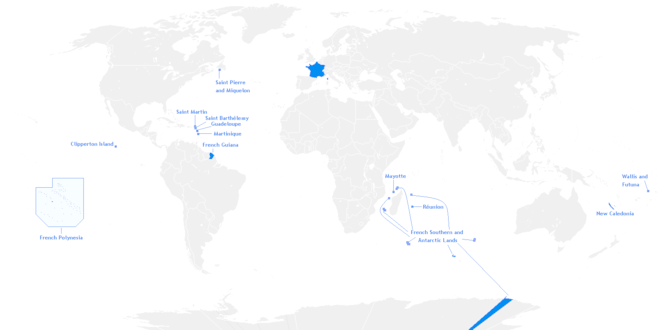

.svg.png) Location of French Polynesia (circled in red) | |

| Sovereign state | France |

| Protectorate proclaimed | 9 September 1842 |

| Territorial status | 27 October 1946 |

| Collectivity status | 28 March 2003 |

| Country status | 27 February 2004 |

| Capital | Papeete 17°34′S 149°36′W |

| Largest city | Fa'a'ā |

| Official languages | French |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (1988[1]) | 66.5% unmixed Polynesians 7.1% mixed Polynesians[lower-alpha 1] 9.3% Demis[lower-alpha 2] 11.9% Europeans[lower-alpha 3] 4.7% East Asians[lower-alpha 4] |

| Demonym(s) | French Polynesian |

| Government | Devolved parliamentary dependency |

• President of the French Republic | Emmanuel Macron |

| Édouard Fritch | |

| Dominique Sorain | |

| Legislature | Assembly of French Polynesia |

| French Parliament | |

• Senate | 3 senators (of 377) |

| 3 seats (of 577) | |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,167 km2 (1,609 sq mi) |

• Land | 3,521.2 km2 (1,359.5 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 12 |

| Population | |

• 2017 census | 275,918[2] (183rd) |

• Density | 78/km2 (202.0/sq mi) (130th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | US$6.163 billion[3] |

| Currency | CFP franc (XPF) |

| Time zone | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Mains electricity |

|

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +689 |

| ISO 3166 code | |

| Internet TLD | .pf |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

.jpg)

French Polynesia is divided into five groups of islands: the Society Islands archipelago, composed of the Windward Islands and the Leeward Islands; the Tuamotu Archipelago; the Gambier Islands; the Marquesas Islands; and the Austral Islands. Among its 118 islands and atolls, 67 are inhabited. Tahiti, which is located within the Society Islands, is the most populous island, having close to 69% of the population of French Polynesia as of 2017. Papeete, located on Tahiti, is the capital. Although not an integral part of its territory, Clipperton Island was administered from French Polynesia until 2007.

Following the Great Polynesian Migration, European explorers visited the islands of French Polynesia on several occasions. Traders and whaling ships also visited. In 1842, the French took over the islands and established a French protectorate they called Établissements français d'Océanie (EFO) (French Establishments/Settlements of Oceania).

In 1946, the EFO became an overseas territory under the constitution of the French Fourth Republic, and Polynesians were granted the right to vote through citizenship. In 1957, the EFO were renamed French Polynesia. In 1983 French Polynesia became a member of the Pacific Community, a regional development organization. Since 28 March 2003, French Polynesia has been an overseas collectivity of the French Republic under the constitutional revision of article 74, and later gained, with law 2004-192 of 27 February 2004, an administrative autonomy, two symbolic manifestations of which are the title of the President of French Polynesia and its additional designation as an overseas country.[4]

History

Scientists believe the Great Polynesian Migration commenced around 1500 BC as Austronesian peoples went on a journey using celestial navigation to find islands in the South Pacific Ocean. The first islands of French Polynesia to be settled were the Marquesas Islands in about 200 BC. The Polynesians later ventured southwest and discovered the Society Islands around AD 300.[5]

European encounters began in 1521 when Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, sailing at the service of the Spanish Crown, sighted Puka-Puka in the Tuāmotu-Gambier Archipelago. In 1606 another Spanish expedition under Pedro Fernandes de Queirós sailed through Polynesia sighting an inhabited island on 10 February[6] which they called Sagitaria (or Sagittaria), probably the island of Rekareka to the southeast of Tahiti.[7] In 1722, Dutchman Jakob Roggeveen while on an expedition sponsored by the Dutch West India Company, charted the location of six islands in the Tuamotu Archipelago and two islands in the Society Islands, one of which was Bora Bora.

British explorer Samuel Wallis became the first European navigator to visit Tahiti in 1767. French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville also visited Tahiti in 1768, while British explorer James Cook arrived in 1769.[5] Cook would stop in Tahiti again in 1773 during his second voyage to the Pacific, and once more in 1777 during his third and last voyage before being killed in Hawaii.

In 1772, the Spanish Viceroy of Peru Don Manuel de Amat ordered a number of expeditions to Tahiti under the command of Domingo de Bonechea who was the first European to explore all of the main islands beyond Tahiti.[8] A short-lived Spanish settlement was created in 1774,[5] and for a time some maps bore the name Isla de Amat after Viceroy Amat.[9] Christian missions began with Spanish priests who stayed in Tahiti for a year. Protestants from the London Missionary Society settled permanently in Polynesia in 1797.

King Pōmare II of Tahiti was forced to flee to Mo'orea in 1803; he and his subjects were converted to Protestantism in 1812. French Catholic missionaries arrived on Tahiti in 1834; their expulsion in 1836 caused France to send a gunboat in 1838. In 1842, Tahiti and Tahuata were declared a French protectorate, to allow Catholic missionaries to work undisturbed. The capital of Papeetē was founded in 1843. In 1880, France annexed Tahiti, changing the status from that of a protectorate to that of a colony. The island groups were not officially united until the establishment of the French protectorate in 1889.[10]

After France declared a protectorate over Tahiti in 1840 and fought a war with Tahiti (1844–1847), the British and French signed the Jarnac Convention in 1847, declaring that the kingdoms of Raiatea, Huahine and Bora Bora were to remain independent from either powers and that no single chief was to be allowed to reign over the entire archipelago. France eventually broke the agreement, and the islands were annexed and became a colony in 1888 (eight years after the Windward Islands) after many native resistances and conflicts called the Leewards War, lasting until 1897.[11][12]

In the 1880s, France claimed the Tuamotu Archipelago, which formerly belonged to the Pōmare Dynasty, without formally annexing it. Having declared a protectorate over Tahuata in 1842, the French regarded the entire Marquesas Islands as French. In 1885, France appointed a governor and established a general council, thus giving it the proper administration for a colony. The islands of Rimatara and Rūrutu unsuccessfully lobbied for British protection in 1888, so in 1889 they were annexed by France. Postage stamps were first issued in the colony in 1892. The first official name for the colony was Établissements de l'Océanie (Establishments in Oceania); in 1903 the general council was changed to an advisory council and the colony's name was changed to Établissements Français de l'Océanie (French Establishments in Oceania).[13]

In 1940, the administration of French Polynesia recognised the Free French Forces and many Polynesians served in World War II. Unknown at the time to the French and Polynesians, the Konoe Cabinet in Imperial Japan on 16 September 1940 included French Polynesia among the many territories which were to become Japanese possessions, as part of the "Eastern Pacific Government-General" in the post-war world.[14] However, in the course of the war in the Pacific the Japanese were not able to launch an actual invasion of the French islands.

In 1946, Polynesians were granted French citizenship and the islands' status was changed to an overseas territory; the islands' name was changed in 1957 to Polynésie Française (French Polynesia). In 1962, France's early nuclear testing ground of Algeria became independent and the Moruroa atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago was selected as the new testing site; tests were conducted underground after 1974.[15] In 1977, French Polynesia was granted partial internal autonomy; in 1984, the autonomy was extended. French Polynesia became a full overseas collectivity of France in 2003.[16]

In September 1995, France stirred up widespread protests by resuming nuclear testing at Fangataufa atoll after a three-year moratorium. The last test was on 27 January 1996. On 29 January 1996, France announced that it would accede to the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and no longer test nuclear weapons.[17]

French Polynesia was relisted in the UN List of Non-Self Governing Territories in 2013, making it eligible for a UN-backed independence referendum. The relisting was made after the indigenous opposition was voiced and supported by the Polynesian Leaders Group, Pacific Conference of Churches, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, Non-Aligned Movement, World Council of Churches, and Melanesian Spearhead Group.[18]

Governance

Under the terms of Article 74 of the French constitution and the Organic Law 2014-192 on the statute of autonomy of French Polynesia, politics of French Polynesia takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic French overseas collectivity, whereby the President of French Polynesia is the head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Assembly of French Polynesia (the territorial assembly).

Political life in French Polynesia has been marked by great instability since the mid-2000s. On 14 September 2007, the pro-independence leader Oscar Temaru, was elected president of French Polynesia for the third time in three years (with 27 of 44 votes cast in the territorial assembly).[19] He replaced former president Gaston Tong Sang, opposed to independence, who lost a no-confidence vote in the Assembly of French Polynesia on 31 August after the longtime former president of French Polynesia, Gaston Flosse, hitherto opposed to independence, sided with his long enemy Oscar Temaru to topple the government of Gaston Tong Sang. Oscar Temaru, however, had no stable majority in the Assembly of French Polynesia, and new territorial elections were held in February 2008 to solve the political crisis.

The party of Gaston Tong Sang won the territorial elections, but that did not solve the political crisis: the two minority parties of Oscar Temaru and Gaston Flosse, who together have one more member in the territorial assembly than the political party of Gaston Tong Sang, allied to prevent Gaston Tong Sang from becoming president of French Polynesia. Gaston Flosse was then elected president of French Polynesia by the territorial assembly on 23 February 2008 with the support of the pro-independence party led by Oscar Temaru, while Oscar Temaru was elected speaker of the territorial assembly with the support of the anti-independence party led by Gaston Flosse. Both formed a coalition cabinet. Many observers doubted that the alliance between the anti-independence Gaston Flosse and the pro-independence Oscar Temaru, designed to prevent Gaston Tong Sang from becoming president of French Polynesia, could last very long.[20]

At the French municipal elections held in March 2008, several prominent mayors who are member of the Flosse-Temaru coalition lost their offices in key municipalities of French Polynesia, which was interpreted as a disapproval of the way Gaston Tong Sang, whose party French Polynesian voters had placed first in the territorial elections the month before, had been prevented from becoming president of French Polynesia by the last minute alliance between Flosse and Temaru's parties. Eventually, on 15 April 2008 the government of Gaston Flosse was toppled by a constructive vote of no confidence in the territorial assembly when two members of the Flosse-Temaru coalition left the coalition and sided with Tong Sang's party. Gaston Tong Sang was elected president of French Polynesia as a result of this constructive vote of no confidence, but his majority in the territorial assembly is very narrow. He offered posts in his cabinet to Flosse and Temaru's parties which they both refused. Gaston Tong Sang has called all parties to help end the instability in local politics, a prerequisite to attract foreign investors needed to develop the local economy.

Administration

Between 1946 and 2003, French Polynesia had the status of an overseas territory (territoire d'outre-mer, or TOM). In 2003, it became an overseas collectivity (collectivité d'outre-mer, or COM). Its statutory law of 27 February 2004 gives it the particular designation of overseas country inside the Republic (pays d'outre-mer au sein de la République, or POM), but without legal modification of its status.

Relations with mainland France

Despite a local assembly and government, French Polynesia is not in a free association with France, like the Cook Islands with New Zealand. As a French overseas collectivity, the local government has no competence in justice, university education, security and defense. Services in these areas are directly provided and administered by the Government of France, including the National Gendarmerie (which also polices rural and border areas in metropolitan France), and French military forces. The collectivity government retains control over primary and secondary education, health, town planning, and the environment.[21] The highest representative of the State in the territory is the High Commissioner of the Republic in French Polynesia (French: Haut commissaire de la République en Polynésie française).

French Polynesia also sends three deputies to the French National Assembly, one representing the Leeward Islands administrative subdivision and the south-western suburbs of Papeete, another one representing Papeete and its north-eastern suburbs, plus the commune (municipality) of Mo'orea-Mai'ao, the Tuāmotu-Gambier administrative division, and the Marquesas Islands administrative division, and the last one representing the rest of Tahiti and the Austral Islands administrative subdivision. French Polynesia also sends two senators to the French Senate.

French Polynesians vote in the French presidential elections. In the 2007 French presidential election, in which the pro-independence leader Oscar Temaru openly called to vote for the Socialist candidate Ségolène Royal while the parties opposed to independence generally supported the center-right candidate Nicolas Sarkozy, the turnout in French Polynesia was 69.12% in the first round of the election and 74.67% in the second round, both in favour of Sarkozy (as compared to Metropolitan France in the 2nd round: Nicolas Sarkozy 51.9%; Ségolène Royal 48.1%).[22]

Geography

The islands of French Polynesia make up a total land area of 3,521 square kilometres (1,359 sq mi),[23] scattered over more than 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) of ocean. There are 118 islands in French Polynesia and many more islets or motus around atolls. The highest point is Mount Orohena on Tahiti.

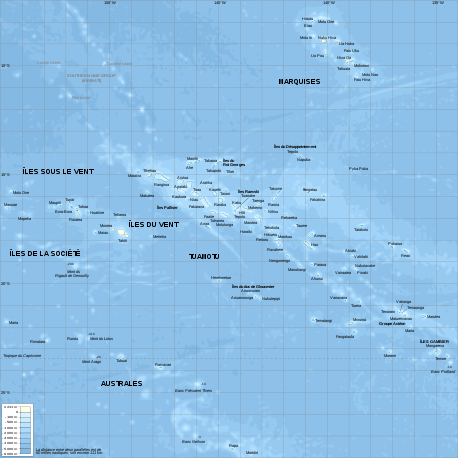

It is made up of six archipelagos. The largest and most populated island is Tahiti, in the Society Islands. The archipelagos are:

| Name | Area (km²) | Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marquesas Islands | 1,049.3 | 9,346 (2017 | administratively making the Marquesas Islands subdivision (12 high islands and 1 atoll); |

| Society Islands | 1,590 | 275,918 (2017) | administratively subdivided into the Windward Islands subdivision (5 high islands) and the Leeward Islands District (5 atolls) |

| Tuamotu Archipelago | 850 | 15,346 (2017) | administratively part of the Tuamotu-Gambier subdivision (80 atolls, grouping over 3,100 islands or islets); |

| Gambier Islands | 29.6 | 1535 (2017) | administratively part of the Tuamotu-Gambier subdivision (2 atolls in genesis); |

| Austral Islands | 152 | 6,965 (2017) | administratively part of the Austral Islands subdivision : (5 atolls); |

- Bass Islands – administratively part of the Austral Islands subdivision (2 atolls).

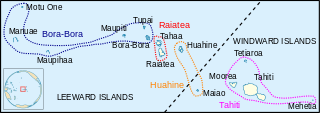

Aside from Tahiti, some other important atolls, islands, and island groups in French Polynesia are: Ahē, Bora Bora, Hiva 'Oa, Huahine, Mai'ao, Maupiti, Meheti'a, Mo'orea, Nuku Hiva, Raiatea, Taha'a, Tetiaroa, Tupua'i and Tūpai.

| Commune | Island | Population (2017) |

|---|---|---|

| Faaa | Tahiti | 29,506 |

| Punaauia | Tahiti | 28,103 |

| Papeete | Tahiti | 26,926 |

Administrative divisions

French Polynesia has five administrative subdivisions (subdivisions administratives):

- Marquesas Islands (French: les îles Marquises or officially la subdivision administrative des îles Marquises)

- Leeward Islands (French: les îles Sous-le-Vent or officially la subdivision administrative des îles Sous-le-Vent) (the two subdivisions administratives Windward Islands and Leeward Islands are part of the Society Islands)

- Windward Islands (French: les îles du Vent or officially la subdivision administrative des îles du Vent) (the two subdivisions administratives Windward Islands and Leeward Islands are part of the Society Islands)

- Tuāmotu-Gambier (French: les Îles Tuamotu-Gambier or officially la subdivision administrative des îles Tuamotu-Gambier) (the Tuamotus and the Gambier Islands)

- Austral Islands (French: les îles Australes or officially la subdivision administrative des îles Australes) (including the Bass Islands)

Demographics

Total population at the August 2017 census was 275,918 inhabitants.[2] At the 2017 census, 68.7% of the population of French Polynesia lived on the island of Tahiti alone.[2] The urban area of Papeete, the capital city, has 136,771 inhabitants (2017 census).

At the 2017 census, 89.0% of people living in French Polynesia were born in French Polynesia (up from 87.3% in 2007), 8.1% were born in metropolitan France (down from 9.3% in 2007), 1.2% were born in overseas France outside of French Polynesia (down from 1.4% in 2007), and 1.7% were born in foreign countries (down from 2.0% in 2007).[24] The population of natives of metropolitan France living in French Polynesia has declined in relative terms since the 1980s, but in absolute terms their population peaked at the 2007 census with 24,265 natives of metropolitan France living in French Polynesia that year (not counting their children born in French Polynesia).[25] With the local economic crisis, their population declined to 22,278 at the 2012 census,[25] and 22,387 at the 2017 census.[24]

| Census | Born in French Polynesia | Born in Metropolitan France | Born in Overseas France | Born in foreign countries with French citizenship at birth¹ | Immigrants² | |

| 2017 | 89.0% | 8.1% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 0.8% | |

| 2012 | 88.7% | 8.3% | 1.3% | 0.9% | 0.8% | |

| 2007 | 87.3% | 9.3% | 1.4% | 1.1% | 0.9% | |

| 2002 | 87.2% | 9.5% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 0.8% | |

| 1996 | 86.9% | 9.3% | 1.5% | 1.3% | 0.9% | |

| 1988 | 86.7% | 9.2% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.0% | |

| 1983 | 86.1% | 10.1% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 1.3% | |

| ¹Persons born abroad of French parents, such as Pieds-Noirs and children of French expatriates. ²An immigrant is by French definition a person born in a foreign country and who didn't have French citizenship at birth. Note that an immigrant may have acquired French citizenship since moving to France, but is still listed as an immigrant in French statistics. On the other hand, persons born in France with foreign citizenship (the children of immigrants) are not listed as immigrants. | ||||||

| Source: ISPF,[25][24] | ||||||

At the 1988 census, the last census which asked questions regarding ethnicity, 66.5% of people were ethnically unmixed Polynesians, 7.1% were ethnically Polynesians with light European and/or East Asian mixing, 11.9% were Europeans (mostly French), 9.3% were people of mixed European and Polynesian descent, the so-called Demis (literally meaning "Half"), and 4.7% were East Asians (mainly Chinese).[1]

Chinese, Demis, and the white populace are essentially concentrated on the island of Tahiti, particularly in the urban area of Papeete, where their share of the population is thus much greater than in French Polynesia overall.[1] Despite a long history of ethnic mixing, ethnic tensions have been growing in recent years, with politicians using a xenophobic discourse and fanning the flame of nationalism.[26][27]

Culture

Languages

French is the only official language of French Polynesia.[31] An organic law of 12 April 1996 states that "French is the official language, Tahitian and other Polynesian languages can be used." At the 2017 census, among the population whose age was 15 and older, 73.9% of people reported that the language they spoke the most at home was French (up from 68.6% at the 2007 census), 20.2% reported that the language they spoke the most at home was Tahitian (down from 24.3% at the 2007 census), 2.6% reported Marquesan and 0.2% the related Mangareva language (same percentages for both at the 2007 census), 1.2% reported any of the Austral languages (down from 1.3% at the 2007 census), 1.0% reported Tuamotuan (down from 1.5% at the 2007 census), 0.6% reported a Chinese dialect (41% of which was Hakka) (down from 1.0% at the 2007 census), and 0.4% another language (more than half of which was English) (down from 0.5% at the 2007 census).[32]

At the same census, 95.2% of people whose age was 15 or older reported that they could speak, read and write French (up from 94.7% at the 2007 census), whereas only 1.3% reported that they had no knowledge of French (down from 2.0% at the 2007 census).[32] 86.5% of people whose age was 15 or older reported that they had some form of knowledge of at least one Polynesian language (up from 86.4% at the 2007 census but down from 87.8% at the 2012 census), whereas 13.5% reported that they had no knowledge of any of the Polynesian languages (down from 13.6% at the 2007 census but up from 12.2% at the 2012 census).[32]

Music

French Polynesia appeared in the world music scene in 1992, recorded by French musicologist Pascal Nabet-Meyer with the release of The Tahitian Choir's recordings of unaccompanied vocal Christian music called himene tārava.[33] This form of singing is common in French Polynesia and the Cook Islands, and is notable for a unique drop in pitch at the end of the phrases, a characteristic formed by several different voices, accompanied by a steady grunting of staccato, nonlexical syllables.[34]

Religion

Christianity is the main religion of the islands. A majority of 54% belongs to various Protestant churches, especially the Maohi Protestant Church, which is the largest and accounts for more than 50% of the population.[35] It traces its origins to Pomare II, the king of Tahiti, who converted from traditional beliefs to the Reformed tradition brought to the islands by the London Missionary Society.

Latin Rite Roman Catholics constitute a large minority of 30% of the population, which has its own ecclesiastical province, comprising the Metropolitan Archdiocese of Papeete and its only suffragan, the Diocese of Taiohae.[36] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had 28,147 members as of 2018.[37] Community of Christ, another denomination within the Latter-Day Saint tradition, claimed 7,990 total French Polynesian members as of 2015[38] including Mareva Arnaud Tchong who serves in the church's governing Council of Twelve Apostles. There were about 3,000 Jehovah's Witnesses in Tahiti as of 2014.[39]

There are an estimated 500 Muslims in French Polynesia,[40]

Sports

Football

The sport of football in the island of Tahiti is run by the Fédération Tahitienne de Football.

Va'a

The Polynesian traditional sport va'a is practiced in all the islands. French Polynesia hosts the Hawaiki nui va'a an international race between Tahiti, Huahine and Bora Bora.

Surfing

French Polynesia is famous for its reef break waves. Teahupo'o is probably the most renowned, regularly ranked in the best waves of the world.[41] This site hosts the annual Billabong Pro Tahiti surf competition, the 7th stop of the World Championship Tour.[42]

Kitesurfing

There are many spots to practice kitesurfing in French Polynesia, with Tahiti, Moorea, Bora-Bora, Maupiti and Raivavae being among the most iconic.[43]

Diving

French Polynesia is internationally known for diving. Each archipelago offers opportunities for divers. Rangiroa and Fakarava in the Tuamotu islands are the most famous spots in the area.[44]

Rugby

Rugby is also popular in French Polynesia, specifically Rugby union.

Economy and infrastructure

.jpg)

The legal tender of French Polynesia is the CFP Franc which has a fixed exchange rate with the Euro. The nominal gross domestic product (or GDP) of French Polynesia in 2014 was 5.623 billion U.S. dollars at market local prices, the sixth-largest economy in Oceania after Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, New Caledonia, and Papua New Guinea.[45] The GDP per capita was $20,098 in 2014 (at market exchange rates, not at PPP), lower than in Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and New Caledonia, but higher than all the independent insular states of Oceania. Both per capita and total figures were significantly lower than those recorded before the financial crisis of 2007–08.[45]

French Polynesia has a moderately developed economy, which is dependent on imported goods, tourism, and the financial assistance of mainland France. Tourist facilities are well developed and are available on the major islands. Main agricultural productions are coconuts (copra), vegetables and fruits. French Polynesia exports noni juice, a high quality vanilla, and the famous black Tahitian pearls which accounted for 55% of exports (in value) in 2008.[46]

French Polynesia's seafloor contains rich deposits of nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper that are not exploited.[47]

In 2008, French Polynesia's imports amounted to 2.2 billion U.S. dollars and exports amounted to 0.2 billion U.S. dollars.[46]

Transportation

There are 53 airports in French Polynesia; 46 are paved.[16] Fa'a'ā International Airport is the only international airport in French Polynesia. Each island has its own airport that serves flights to other islands. Air Tahiti is the main airline that flies around the islands.

Communication

In 2017, Alcatel Submarine Networks, a unit of Nokia, launched a massive project to connect many of the islands in French Polynesia with underwater fiber optic cable. The project, called NATITUA will improve French Polynesian broadband connectivity by linking Tahiti to 10 islands in the Tuamotu and Marquesas archipelagos.[48] In August 2018, a celebration was held to commemorate the arrival of a submarine cable from Papeete to the atoll of Hao, extending the network by about 1000 kilometres.[49]

Notable people

- Taïna Barioz (born 1988), World Champion skier representing France.

- Billy Besson, Olympic sailor representing France

- Michel Bourez (born 1985), professional surfer.

- Cheyenne Brando (1970–1995), model, daughter of Marlon Brando and Tarita Teriipaia.

- Jacques Brel (1929–1978), Belgian musician who lived in French Polynesia near the end of his life.

- Jean Gabilou, singer (born 1944), represented France in the 1981 Eurovision Song Contest.

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), French post-impressionist painter who spent the last years of his life in French Polynesia.

- Vaitiare Hirson-Asars (born 1964), actress.

- Ella Koon (born 1979), singer, actress and model.

- Karina Lombard (born 1969), French-American model and actress.

- Pouvāna'a 'Ō'opa (1895–1977), politician and Tahitian nationalist.

- Fabrice Santoro (born 1972), professional tennis player.

- Tarita Teriipaia (born 1941), actress, third wife of Marlon Brando.

- Marama Vahirua (born 1980), footballer, cousin of Pascal Vahirua.

- Pascal Vahirua (born 1966), French former international footballer.

- Célestine Hitiura Vaite (born 1966), writer.

See also

- Outline of French Polynesia

- Index of French Polynesia-related articles

- List of colonial and departmental heads of French Polynesia

- French colonial empire

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Lists of islands

Notes

- Polynesians with light European and/or East Asian mixing.

- Mixed European and Polynesian descent.

- Mostly French.

- Mostly Chinese.

References

- Most recent ethnic census, in 1988. "Frontières ethniques et redéfinition du cadre politique à Tahiti" (PDF). Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "La population légale au 17 août 2017 : 275 918 habitants". ISPF. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ISPF. "Les grands indicateurs des comptes économiques". ispf.pf (in French). Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "Les statuts de la Nouvelle-Calédonie et de la Polynésie". Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Ganse, Alexander. "History of Polynesia, before 1797". Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- James Burney (1803) A Chronological History of the Voyages or Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean, Vol. 5, London, p. 222

- Geo. Collingridge (1903). "Who Discovered Tahiti?". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 12 (3): 184–186.

- Kirk, Robert K. (8 November 2012). Paradise Past: The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520–1920. ISBN 9780786492985. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Manso Porto, Carmen (1997). Cartografía histórica de América: catálogo de manuscritos (in Spanish). Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. p. 10. ISBN 9788489512023.

- Ganse, Alexander. "History of French Polynesia, 1797 to 1889". Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- Robert D. Craig (2002). Historical Dictionary of Polynesia. 39 (2 ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-8108-4237-8.

- Matt K. Matsuda (2005). "Society Islands: Tahitian Archives". Empire of Love: Histories of France and the Pacific. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–112. ISBN 0-19-516294-3.

- Ganse, Alexander. "History of French Polynesia, 1889 to 1918". Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- The Japanese claim to the French Pacific islands, along with many other vast territories, appears in 16 September 1940 "Sphere of survival for the Establishment of a New Order in Greater East Asia by Imperial Japan", published in 1955 by Japan's Foreign Ministry as part of the two-volume "Chronology and major documents of Diplomacy of Japan 1840–1945" – here quoted from "Interview with Tetsuzo Fuwa: Japan's War: History of Expansionism", Japan Press Service, July 2007

- Ganse, Alexander. "History of Polynesia, 1939 to 1977". Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- "French Polynesia". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- Whitney, Craig R (30 January 1996). "France Ending Nuclear Tests That Caused Broad Protests". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- Reeves, Rachel; Hunt, Luke (10 October 2012). "French Polynesia Battles for Independence". The Diplomat. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "BBC NEWS, French Polynesia gets new leader". BBC News. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Polynésie : Gaston Flosse présente un gouvernement d'union" [Polynesia: Gaston Flosse announces a unity government]. RFO (in French). 29 February 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- Rachel Reeves; Luke Hunt; The Diplomat. "French Polynesia Battles for Independence". The Diplomat. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Minister of the Interior, Government of France. "POLYNESIE FRANCAISE (987) (résultats officiels)" (in French). Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "R1- Population sans doubles comptes, des subdivisions, communes et communes associées de Polynésie française, de 1971 à 1996". ISPF. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- Institut Statistique de Polynésie Française (ISPF). "Recensement 2017 – Données détaillées - Migrations" (in French). Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- "Recensements de la population - Evolution des caractéristiques socio-démographiques". ISPF. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- "Logiques " autonomiste " et " indépendantiste " en Polynésie française". Conflits.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Temaru-Flosse: le rebond du nationalisme tahitien". Rue89.com. 19 January 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Population des communes de Polynésie française au RP 2007". INSEE. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- "Population statistique des communes et communes associées aux recensements de 1971 à 2002". ISPF. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- Censuses from 1907 to 1962 in Population, 1972, #4–5, pp. 705–706, published by INED

- Le tahitien reste interdit à l'assemblée de Polynésie, RFO, 6 October 2010

- Institut Statistique de Polynésie Française (ISPF). "Recensement 2017 – Données détaillées Langues". Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- Hayward, Philip (2006). Bounty Chords: Music, Dance and Cultural Heritage on Norfolk and Pitcairn Islands. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 24–35. ISBN 9780861966783.

- McLean, Mervyn (1999). Weavers of Song: Polynesian Music and Dance. Auckland University Press. pp. 403–435. ISBN 9781869402129.

- "126th Maohi Protestant Church Synod to last one week". Tahitipresse. 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- "Catholic Church in Territory of French Polynesia". GCatholic. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- LDS Newsroom Statistical Information. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Saturday/Sunday Bulletin World Conference 2016. Community of Christ. 2016. pp. 46–47.

- 2015 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses. Watch Tower Society. p. 186.

- State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2014 - Case study: Tahiti: Islamophobia in French Polynesia

- By Jade Bremner, for. "World's 50 best surf spots - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "2019 Tahiti Pro Teahupo'o". World Surf League. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- GR3G. "General Info - WWW.TaHiTi-KiTeSuRF.COM". tahiti-kitesurf.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "Top 100 Destination: Diving in French Polynesia". Scuba Diving. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "French Polynesia". United Nations. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Institut d'émission d'Outre-Mer (IEOM). "La Polynésie française en 2008" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Manheim, F. T. (1986). "Marine Cobalt Resources". Science. 232 (4750): 600–608. doi:10.1126/science.232.4750.600. ISSN 0036-8075.

- "NATITUA submarine cable system to bridge French Polynesian digital divide". lightwaveonline.com. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Submarine cable extended to French Polynesia's Hao". Radio New Zealand. 7 August 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

Bibliography

- Danielsson, Bengt (1965). Work and Life on Raroia: An Acculturation Study from the Tuamotu Group, French Oceania. London: G. Allen & Unwin.

- Danielsson, Bengt; Marie-Thérèse Danielsson (1986). Poisoned Reign: French Nuclear Colonialism in the Pacific. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-008130-5.

- Hough, Richard (1995). Captain James Cook. W W Norton. ISBN 0-393-03680-4.

- Pollock, Nancy J.; Ron Crocombe, eds. (1988). French Polynesia: A Book of Selected Readings. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies of the University of the South Pacific. ISBN 982-02-0032-6.

- Thompson, Virginia; Richard Adloff (1971). The French Pacific Islands: French Polynesia and New Caledonia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Aldrich, Robert (1990). The French Presence in the South Pacific, 1842–1940. Sydney.

- Aldrich, Robert (1993). France and the South Pacific since 1940. Sydney.

- James Rogers and Luis Simón. The Status and Location of the Military Installations of the Member States of the European Union and Their Potential Role for the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP). Brussels: European Parliament, 2009. 25 pp.

- Jean-Marc Régnault, Le pouvoir confisqué en Polynésie française. L'affrontement Temaru-Flosse. Les Indes savantes, 2005.

External links

| The Wikibook Geography of France has a page on the topic of: French Polynesia |

- Government

- High Commission of the Republic in French Polynesia

- Presidency of French Polynesia

- Assembly of French Polynesia

- Legal publication service in French Polynesia

- Administrative Subdivisions of French Polynesia

- General information

- (in French) Encyclopédie collaborative du patrimoine culturel et naturel polynésien

- "French Polynesia". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- French Polynesia at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- French Polynesia at Curlie

- Travel

.svg.png)