London

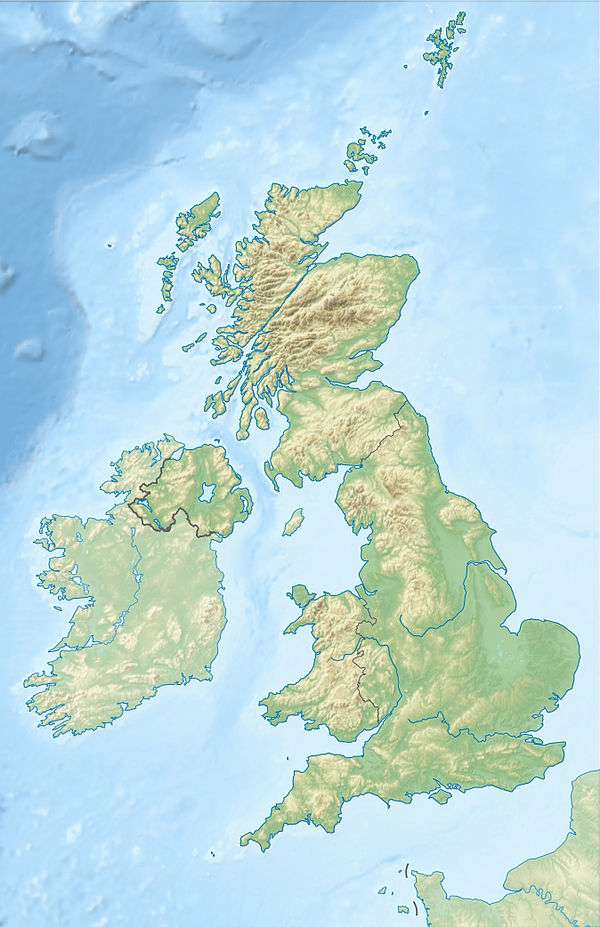

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom.[7][8] The city stands on the River Thames in the south-east of England, at the head of its 50-mile (80 km) estuary leading to the North Sea, London has been a major settlement for two millennia. Londinium was founded by the Romans.[9] The City of London, London's ancient core and financial centre − an area of just 1.12 square miles (2.9 km2) and colloquially known as the Square Mile − retains boundaries that closely follow its medieval limits.[10][11][12][13][14][note 1] The adjacent City of Westminster is an Inner London borough and has for centuries been the location of much of the national government. Thirty one additional boroughs north and south of the river also comprise modern London. London is governed by the mayor of London and the London Assembly.[15][note 2][16]

London | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: City of London in the foreground with Canary Wharf in the far background, Trafalgar Square, London Eye, Tower Bridge and a London Underground roundel in front of Elizabeth Tower | |

London Location within the United Kingdom  London Location within England  London Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 51°30′26″N 0°7′39″W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | London (coterminous) |

| Counties | Greater London City of London |

| Settled by Romans | AD 47[1] as Londinium |

| Districts | City of London & 32 boroughs |

| Government | |

| • Type | Executive mayoralty and deliberative assembly within unitary constitutional monarchy |

| • Body | Greater London Authority • Mayor Sadiq Khan, L • London Assembly |

| • London Assembly | 14 constituencies |

| • UK Parliament | 73 constituencies |

| Area | |

| • Total[upper-alpha 1] | 607 sq mi (1,572 km2) |

| • Urban | 671.0 sq mi (1,737.9 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,236 sq mi (8,382 km2) |

| • City of London | 1.12 sq mi (2.90 km2) |

| • Greater London | 606 sq mi (1,569 km2) |

| Elevation | 36 ft (11 m) |

| Population (2018)[3] | |

| • Total[upper-alpha 1] | 8,961,989[4] |

| • Density | 14,670/sq mi (5,666/km2) |

| • Urban | 9,787,426 |

| • Metro | 14,257,962[5] (1st) |

| • City of London | 8,706 (67th) |

| • Greater London | 8,899,375 |

| Demonyms | Londoner |

| GVA (2018) | |

| • Total | £487 billion ($649 billion) |

| • Per capita | £54,686 ($72,915) |

| Time zone | UTC (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Area codes |

|

| Police | City of London Metropolitan |

| Fire and rescue | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| Airports | Heathrow (LHR) City (LCY) Outside London: Gatwick (LGW) Stansted (STN) Luton (LTN) Southend (SEN) |

| GeoTLD | .london |

| Website | london.gov.uk |

London is considered to be one of the world's most important global cities[17][18][19] and has been called the world's most powerful,[20] most desirable,[21] most influential,[22] most visited,[23] most expensive,[24][25] sustainable,[26] most investment-friendly,[27] and most-popular-for-work[28] city. It exerts a considerable impact upon the arts, commerce, education, entertainment, fashion, finance, healthcare, media, professional services, research and development, tourism and transportation.[29][30] London ranks 26th out of 300 major cities for economic performance.[31] It is one of the largest financial centres[32] and has either the fifth or the sixth-largest metropolitan area GDP.[note 3][33][34][35][36][37] It is the most-visited city as measured by international arrivals[38] and has the busiest city airport system as measured by passenger traffic.[39] It is the leading investment destination,[40] [41][42][43] hosting more international retailers[44][45] than any other city. As of 2020, London has the second-highest number of billionaires of any city in Europe, after Moscow.[46] In 2019, London had the highest number of ultra high-net-worth individuals in Europe.[47] London's universities form the largest concentration of higher education institutes in Europe,[48] and London is home to highly ranked institutions such as Imperial College London in natural and applied sciences, and the London School of Economics in social sciences.[49][50][51] In 2012, London became the first city to have hosted three modern Summer Olympic Games.[52]

London has a diverse range of people and cultures, and more than 300 languages are spoken in the region.[53] Its estimated mid-2018 municipal population (corresponding to Greater London) was 8,908,081,[3] the third most populous of any city in Europe[54] and accounts for 13.4% of the UK population.[55] London's urban area is the third most populous in Europe, after Moscow and Paris, with 9,787,426 inhabitants at the 2011 census.[56] The London commuter belt is the second-most populous in Europe, after the Moscow Metropolitan Area, with 14,040,163 inhabitants in 2016.[note 4][5][57]

London contains four World Heritage Sites: the Tower of London; Kew Gardens; the site comprising the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey, and St Margaret's Church; and the historic settlement in Greenwich where the Royal Observatory, Greenwich defines the Prime Meridian (0° longitude) and Greenwich Mean Time.[58] Other landmarks include Buckingham Palace, the London Eye, Piccadilly Circus, St Paul's Cathedral, Tower Bridge, Trafalgar Square and The Shard. London has numerous museums, galleries, libraries and sporting events. These include the British Museum, National Gallery, Natural History Museum, Tate Modern, British Library and West End theatres.[59] The London Underground is the oldest underground railway network in the world.

Toponymy

London is an ancient name, already attested in the first century AD, usually in the Latinised form Londinium;[60] for example, handwritten Roman tablets recovered in the city originating from AD 65/70–80 include the word Londinio ('in London').[61]

Over the years, the name has attracted many mythicising explanations. The earliest attested appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, written around 1136.[60] This had it that the name originated from a supposed King Lud, who had allegedly taken over the city and named it Kaerlud.[62]

Modern scientific analyses of the name must account for the origins of the different forms found in early sources: Latin (usually Londinium), Old English (usually Lunden), and Welsh (usually Llundein), with reference to the known developments over time of sounds in those different languages. It is agreed that the name came into these languages from Common Brythonic; recent work tends to reconstruct the lost Celtic form of the name as *Londonjon or something similar. This was adapted into Latin as Londinium and borrowed into Old English, the ancestor-language of English.[63]

The toponymy of the Common Brythonic form is much debated. A prominent explanation was Richard Coates's 1998 argument that the name derived from pre-Celtic Old European *(p)lowonida, meaning "river too wide to ford". Coates suggested that this was a name given to the part of the River Thames which flows through London; from this, the settlement gained the Celtic form of its name, *Lowonidonjon.[64] However, most work has accepted a Celtic origin for the name, and recent studies have favoured an explanation along the lines of a Celtic derivative of a Proto-Indo-European root *lendh- ('sink, cause to sink'), combined with the Celtic suffix *-injo- or *-onjo- (used to form place-names). Peter Schrijver has specifically suggested, on these grounds, that the name originally meant 'place that floods (periodically, tidally)'.[65][63]

Until 1889, the name "London" applied officially to the City of London, but since then it has also referred to the County of London and Greater London.[66]

In writing, "London" is, on occasion, colloquially contracted to "LDN".[67] Such usage originated in SMS language, and is often found, on a social media user profile, suffixing an alias or handle.

History

Prehistory

In 1993, the remains of a Bronze Age bridge were found on the south foreshore, upstream of Vauxhall Bridge.[68] This bridge either crossed the Thames or reached a now lost island in it. Two of those timbers were radiocarbon dated to between 1750 BC and 1285 BC.[68]

In 2010, the foundations of a large timber structure, dated to between 4800 BC and 4500 BC,[69] were found on the Thames's south foreshore, downstream of Vauxhall Bridge.[70] The function of the mesolithic structure is not known. Both structures are on the south bank where the River Effra flows into the Thames.[70]

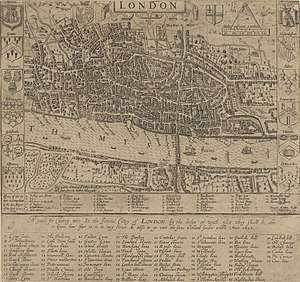

Roman London

Although there is evidence of scattered Brythonic settlements in the area, the first major settlement was founded by the Romans about four years[1] after the invasion of AD 43.[71] This lasted only until around AD 61, when the Iceni tribe led by Queen Boudica stormed it, burning the settlement to the ground.[72] The next, heavily planned, incarnation of Londinium prospered, and it superseded Colchester as the capital of the Roman province of Britannia in 100. At its height in the 2nd century, Roman London had a population of around 60,000.[73]

Anglo-Saxon and Viking period London

With the collapse of Roman rule in the early 5th century, London ceased to be a capital, and the walled city of Londinium was effectively abandoned, although Roman civilisation continued in the area of St Martin-in-the-Fields until around 450.[74] From around 500, an Anglo-Saxon settlement known as Lundenwic developed slightly west of the old Roman city.[75] By about 680, the city had regrown into a major port, although there is little evidence of large-scale production. From the 820s repeated Viking assaults brought decline. Three are recorded; those in 851 and 886 succeeded, while the last, in 994, was rebuffed.[76]

.jpg)

The Vikings established Danelaw over much of eastern and northern England; its boundary stretched roughly from London to Chester. It was an area of political and geographical control imposed by the Viking incursions which was formally agreed by the Danish warlord, Guthrum and the West Saxon king Alfred the Great in 886. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that Alfred "refounded" London in 886. Archaeological research shows that this involved abandonment of Lundenwic and a revival of life and trade within the old Roman walls. London then grew slowly until about 950, after which activity increased dramatically.[77]

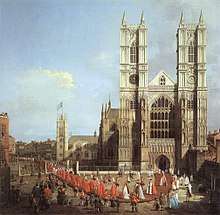

By the 11th century, London was beyond all comparison the largest town in England. Westminster Abbey, rebuilt in the Romanesque style by King Edward the Confessor, was one of the grandest churches in Europe. Winchester had previously been the capital of Anglo-Saxon England, but from this time on, London became the main forum for foreign traders and the base for defence in time of war. In the view of Frank Stenton: "It had the resources, and it was rapidly developing the dignity and the political self-consciousness appropriate to a national capital."[78][79]

Middle Ages

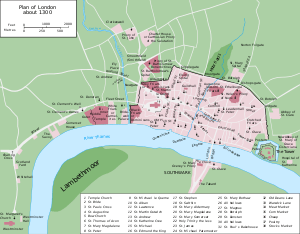

After winning the Battle of Hastings, William, Duke of Normandy was crowned King of England in the newly completed Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066.[80] William constructed the Tower of London, the first of the many Norman castles in England to be rebuilt in stone, in the southeastern corner of the city, to intimidate the native inhabitants.[81] In 1097, William II began the building of Westminster Hall, close by the abbey of the same name. The hall became the basis of a new Palace of Westminster.[82][83]

In the 12th century, the institutions of central government, which had hitherto accompanied the royal English court as it moved around the country, grew in size and sophistication and became increasingly fixed in one place. For most purposes this was Westminster, although the royal treasury, having been moved from Winchester, came to rest in the Tower. While the City of Westminster developed into a true capital in governmental terms, its distinct neighbour, the City of London, remained England's largest city and principal commercial centre, and it flourished under its own unique administration, the Corporation of London. In 1100, its population was around 18,000; by 1300 it had grown to nearly 100,000.[84] Disaster struck in the form of the Black Death in the mid-14th century, when London lost nearly a third of its population.[85] London was the focus of the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.[86]

London was also a centre of England's Jewish population before their expulsion by Edward I in 1290. Violence against Jews took place in 1190, after it was rumoured that the new king had ordered their massacre after they had presented themselves at his coronation.[87] In 1264 during the Second Barons' War, Simon de Montfort's rebels killed 500 Jews while attempting to seize records of debts.[88]

Early modern

During the Tudor period the Reformation produced a gradual shift to Protestantism, and much of London property passed from church to private ownership, which accelerated trade and business in the city.[89] In 1475, the Hanseatic League set up its main trading base (kontor) of England in London, called the Stalhof or Steelyard. It existed until 1853, when the Hanseatic cities of Lübeck, Bremen and Hamburg sold the property to South Eastern Railway.[90] Woollen cloth was shipped undyed and undressed from 14th/15th century London to the nearby shores of the Low Countries, where it was considered indispensable.[91]

But the reach of English maritime enterprise hardly extended beyond the seas of north-west Europe. The commercial route to Italy and the Mediterranean Sea normally lay through Antwerp and over the Alps; any ships passing through the Strait of Gibraltar to or from England were likely to be Italian or Ragusan. Upon the re-opening of the Netherlands to English shipping in January 1565, there ensued a strong outburst of commercial activity.[92] The Royal Exchange was founded.[93] Mercantilism grew, and monopoly trading companies such as the East India Company were established, with trade expanding to the New World. London became the principal North Sea port, with migrants arriving from England and abroad. The population rose from an estimated 50,000 in 1530 to about 225,000 in 1605.[89]

In the 16th century William Shakespeare and his contemporaries lived in London at a time of hostility to the development of the theatre. By the end of the Tudor period in 1603, London was still very compact. There was an assassination attempt on James I in Westminster, in the Gunpowder Plot on 5 November 1605.[94]

In 1637, the government of Charles I attempted to reform administration in the area of London. The plan called for the Corporation of the city to extend its jurisdiction and administration over expanding areas around the city. Fearing an attempt by the Crown to diminish the Liberties of London, a lack of interest in administering these additional areas, or concern by city guilds of having to share power, the Corporation refused. Later called "The Great Refusal", this decision largely continues to account for the unique governmental status of the City.[95]

In the English Civil War the majority of Londoners supported the Parliamentary cause. After an initial advance by the Royalists in 1642, culminating in the battles of Brentford and Turnham Green, London was surrounded by a defensive perimeter wall known as the Lines of Communication. The lines were built by up to 20,000 people, and were completed in under two months.[96] The fortifications failed their only test when the New Model Army entered London in 1647,[97] and they were levelled by Parliament the same year.[98]

London was plagued by disease in the early 17th century,[99] culminating in the Great Plague of 1665–1666, which killed up to 100,000 people, or a fifth of the population.[100]

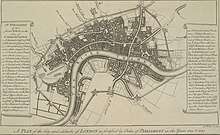

The Great Fire of London broke out in 1666 in Pudding Lane in the city and quickly swept through the wooden buildings.[101] Rebuilding took over ten years and was supervised by Robert Hooke[102][103][104] as Surveyor of London.[105] In 1708 Christopher Wren's masterpiece, St Paul's Cathedral was completed. During the Georgian era, new districts such as Mayfair were formed in the west; new bridges over the Thames encouraged development in South London. In the east, the Port of London expanded downstream. London's development as an international financial centre matured for much of the 1700s.

In 1762, George III acquired Buckingham House and it was enlarged over the next 75 years. During the 18th century, London was dogged by crime, and the Bow Street Runners were established in 1750 as a professional police force.[106] In total, more than 200 offences were punishable by death,[107] including petty theft.[108] Most children born in the city died before reaching their third birthday.[109]

The coffeehouse became a popular place to debate ideas, with growing literacy and the development of the printing press making news widely available; and Fleet Street became the centre of the British press. Following the invasion of Amsterdam by Napoleonic armies, many financiers relocated to London, especially a large Jewish community, and the first London international issue was arranged in 1817. Around the same time, the Royal Navy became the world leading war fleet, acting as a serious deterrent to potential economic adversaries of the United Kingdom. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 was specifically aimed at weakening Dutch economic power. London then overtook Amsterdam as the leading international financial centre.[110] In 1888, London became home to a series of murders by a man known only as Jack the Ripper and It has since become one of the world's most famous unsolved mysteries.

According to Samuel Johnson:

You find no man, at all intellectual, who is willing to leave London. No, Sir, when a man is tired of London, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.

Late modern and contemporary

London was the world's largest city from c.1831 to 1925,[112] with a population density of 325 people per hectare.[113] London's overcrowded conditions led to cholera epidemics,[114] claiming 14,000 lives in 1848, and 6,000 in 1866.[115] Rising traffic congestion led to the creation of the world's first local urban rail network. The Metropolitan Board of Works oversaw infrastructure expansion in the capital and some of the surrounding counties; it was abolished in 1889 when the London County Council was created out of those areas of the counties surrounding the capital.

London was bombed by the Germans during the First World War,[116] and during the Second World War, the Blitz and other bombings by the German Luftwaffe killed over 30,000 Londoners, destroying large tracts of housing and other buildings across the city.[117]

Immediately after the War, the 1948 Summer Olympics were held at the original Wembley Stadium, at a time when London was still recovering from the war.[118] From the 1940s onwards, London became home to many immigrants, primarily from Commonwealth countries such as Jamaica, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan,[119] making London one of the most diverse cities worldwide. In 1951, the Festival of Britain was held on the South Bank.[120] The Great Smog of 1952 led to the Clean Air Act 1956, which ended the "pea soup fogs" for which London had been notorious.[121]

Primarily starting in the mid-1960s, London became a centre for the worldwide youth culture, exemplified by the Swinging London subculture[122] associated with the King's Road, Chelsea[123] and Carnaby Street.[124] The role of trendsetter was revived during the punk era.[125] In 1965 London's political boundaries were expanded to take into account the growth of the urban area and a new Greater London Council was created.[126] During The Troubles in Northern Ireland, London was subjected to bombing attacks by the Provisional Irish Republican Army[127] for two decades, starting with the Old Bailey bombing in 1973.[128][129] Racial inequality was highlighted by the 1981 Brixton riot.[130]

Greater London's population declined steadily in the decades after the Second World War, from an estimated peak of 8.6 million in 1939 to around 6.8 million in the 1980s.[131] The principal ports for London moved downstream to Felixstowe and Tilbury, with the London Docklands area becoming a focus for regeneration, including the Canary Wharf development. This was borne out of London's ever-increasing role as a major international financial centre during the 1980s.[132] The Thames Barrier was completed in the 1980s to protect London against tidal surges from the North Sea.[133]

The Greater London Council was abolished in 1986, which left London without a central administration until 2000 when London-wide government was restored, with the creation of the Greater London Authority.[134] To celebrate the start of the 21st century, the Millennium Dome, London Eye and Millennium Bridge were constructed.[135] On 6 July 2005 London was awarded the 2012 Summer Olympics, making London the first city to stage the Olympic Games three times.[136] On 7 July 2005, three London Underground trains and a double-decker bus were bombed in a series of terrorist attacks.[137]

In 2008, Time named London alongside New York City and Hong Kong as Nylonkong, hailing it as the world's three most influential global cities.[138] In January 2015, Greater London's population was estimated to be 8.63 million, the highest level since 1939.[139] During the Brexit referendum in 2016, the UK as a whole decided to leave the European Union, but a majority of London constituencies voted to remain in the EU.[140]

Administration

.jpg) |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of London |

|

|

|

Local government

The administration of London is formed of two tiers: a citywide, strategic tier and a local tier. Citywide administration is coordinated by the Greater London Authority (GLA), while local administration is carried out by 33 smaller authorities.[141] The GLA consists of two elected components: the mayor of London, who has executive powers, and the London Assembly, which scrutinises the mayor's decisions and can accept or reject the mayor's budget proposals each year. The headquarters of the GLA is City Hall, Southwark. The mayor since 2016 has been Sadiq Khan, the first Muslim mayor of a major Western capital.[142][143] The mayor's statutory planning strategy is published as the London Plan, which was most recently revised in 2011.[144] The local authorities are the councils of the 32 London boroughs and the City of London Corporation.[145] They are responsible for most local services, such as local planning, schools, social services, local roads and refuse collection. Certain functions, such as waste management, are provided through joint arrangements. In 2009–2010 the combined revenue expenditure by London councils and the GLA amounted to just over £22 billion (£14.7 billion for the boroughs and £7.4 billion for the GLA).[146]

The London Fire Brigade is the statutory fire and rescue service for Greater London. It is run by the London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority and is the third largest fire service in the world.[147] National Health Service ambulance services are provided by the London Ambulance Service (LAS) NHS Trust, the largest free-at-the-point-of-use emergency ambulance service in the world.[148] The London Air Ambulance charity operates in conjunction with the LAS where required. Her Majesty's Coastguard and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution operate on the River Thames,[149][150] which is under the jurisdiction of the Port of London Authority from Teddington Lock to the sea.[151]

National government

London is the seat of the Government of the United Kingdom. Many government departments, as well as the prime minister's residence at 10 Downing Street, are based close to the Palace of Westminster, particularly along Whitehall.[152] There are 73 members of Parliament (MPs) from London, elected from local parliamentary constituencies in the national Parliament. As of December 2019, 49 are from the Labour Party, 21 are Conservatives, and three are Liberal Democrat.[153] The ministerial post of minister for London was created in 1994. The current Minister for London is Paul Scully MP.[154]

Policing and crime

Policing in Greater London, with the exception of the City of London, is provided by the Metropolitan Police, overseen by the mayor through the Mayor's Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC).[155][156] The City of London has its own police force – the City of London Police.[157] The British Transport Police are responsible for police services on National Rail, London Underground, Docklands Light Railway and Tramlink services.[158] A fourth police force in London, the Ministry of Defence Police, do not generally become involved with policing the general public.

Crime rates vary widely by area, ranging from parts with serious issues to parts considered very safe. Today crime figures are made available nationally at Local Authority[159] and Ward level.[160] In 2015, there were 118 homicides, a 25.5% increase over 2014.[161] The Metropolitan Police have made detailed crime figures, broken down by category at borough and ward level, available on their website since 2000.[162]

Recorded crime has been rising in London, notably violent crime and murder by stabbing and other means have risen. There have been 50 murders from the start of 2018 to mid April 2018. Funding cuts to police in London are likely to have contributed to this, though other factors are also involved.[163]

Geography

Scope

London, also referred to as Greater London, is one of nine regions of England and the top-level subdivision covering most of the city's metropolis.[note 5] The small ancient City of London at its core once comprised the whole settlement, but as its urban area grew, the Corporation of London resisted attempts to amalgamate the city with its suburbs, causing "London" to be defined in a number of ways for different purposes.[164]

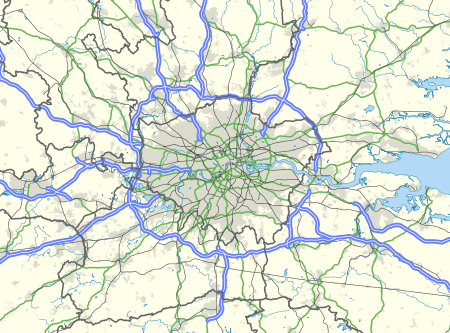

Forty per cent of Greater London is covered by the London post town, within which 'LONDON' forms part of postal addresses.[165][166] The London telephone area code (020) covers a larger area, similar in size to Greater London, although some outer districts are excluded and some places just outside are included. The Greater London boundary has been aligned to the M25 motorway in places.[167]

Outward urban expansion is now prevented by the Metropolitan Green Belt,[168] although the built-up area extends beyond the boundary in places, resulting in a separately defined Greater London Urban Area. Beyond this is the vast London commuter belt.[169] Greater London is split for some purposes into Inner London and Outer London.[170] The city is split by the River Thames into North and South, with an informal central London area in its interior. The coordinates of the nominal centre of London, traditionally considered to be the original Eleanor Cross at Charing Cross near the junction of Trafalgar Square and Whitehall, are about 51°30′26″N 00°07′39″W.[171] However the geographical centre of London, on one definition, is in the London Borough of Lambeth, just 0.1 miles to the northeast of Lambeth North tube station.[172]

Status

Within London, both the City of London and the City of Westminster have city status and both the City of London and the remainder of Greater London are counties for the purposes of lieutenancies.[173] The area of Greater London includes areas that are part of the historic counties of Middlesex, Kent, Surrey, Essex and Hertfordshire.[174] London's status as the capital of England, and later the United Kingdom, has never been granted or confirmed officially—by statute or in written form.[note 6]

Its position was formed through constitutional convention, making its status as de facto capital a part of the UK's uncodified constitution. The capital of England was moved to London from Winchester as the Palace of Westminster developed in the 12th and 13th centuries to become the permanent location of the royal court, and thus the political capital of the nation.[178] More recently, Greater London has been defined as a region of England and in this context is known as London.[13]

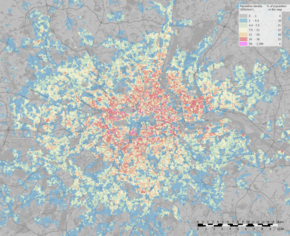

Topography

Greater London encompasses a total area of 1,583 square kilometres (611 sq mi), an area which had a population of 7,172,036 in 2001 and a population density of 4,542 inhabitants per square kilometre (11,760/sq mi). The extended area known as the London Metropolitan Region or the London Metropolitan Agglomeration, comprises a total area of 8,382 square kilometres (3,236 sq mi) has a population of 13,709,000 and a population density of 1,510 inhabitants per square kilometre (3,900/sq mi).[179] Modern London stands on the Thames, its primary geographical feature, a navigable river which crosses the city from the south-west to the east. The Thames Valley is a floodplain surrounded by gently rolling hills including Parliament Hill, Addington Hills, and Primrose Hill. Historically London grew up at the lowest bridging point on the Thames. The Thames was once a much broader, shallower river with extensive marshlands; at high tide, its shores reached five times their present width.[180]

Since the Victorian era the Thames has been extensively embanked, and many of its London tributaries now flow underground. The Thames is a tidal river, and London is vulnerable to flooding.[181] The threat has increased over time because of a slow but continuous rise in high water level by the slow 'tilting' of the British Isles (up in Scotland and Northern Ireland and down in southern parts of England, Wales and Ireland) caused by post-glacial rebound.[182][183]

In 1974 a decade of work began on the construction of the Thames Barrier across the Thames at Woolwich to deal with this threat. While the barrier is expected to function as designed until roughly 2070, concepts for its future enlargement or redesign are already being discussed.[184]

Climate

| London, United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

London has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb ) receiving less precipitation than Rome, Bordeaux, Lisbon, Naples, Sydney or New York City.[185][186][187][188][189][190] Rainfall records have been kept in the city since at least 1697, when records began at Kew. At Kew, the most rainfall in one month is 7.44 inches (189.0 mm) in November 1755 and the least is 0 inches (0.00 mm) in both December 1788 and July 1800. Mile End also had 0 inches (0.00 mm) in April 1893.[191] The wettest year on record is 1903, with a total fall of 38.17 inches (969.4 mm) and the driest is 1921, with a total fall of 12.14 inches (308.3 mm).[192]

Temperature extremes in London range from 38.1 °C (100.6 °F) at Kew during August 2003[193] down to −21.1 °C (−6.0 °F).[194] However, an unofficial reading of −24 °C (−11 °F) was reported on 3 January 1740.[195] Conversely, the highest unofficial temperature ever known to be recorded in the United Kingdom occurred in London in the 1808 heat wave. The temperature was recorded at 105 °F (40.6 °C) on 13 July. It is thought that this temperature, if accurate, is one of the highest temperatures of the millennium in the United Kingdom. It is thought that only days in 1513 and 1707 could have beaten this.[196] Since records began in London (first at Greenwich in 1841[197]), the warmest month on record is July 1868, with a mean temperature of 22.5 °C (72.5 °F) at Greenwich whereas the coldest month is December 2010, with a mean temperature of −6.7 °C (19.9 °F) at Northolt.[198] Records for atmospheric pressure have been kept at London since 1692. The highest pressure ever reported is 1,050 millibars (31 inHg) on 20 January 2020, and the lowest is 945.8 millibars (27.93 inHg) on 25 December 1821.[199][200]

Summers are generally warm, sometimes hot. London's average July high is 24 °C (74 °F). On average each year, London experiences 31 days above 25 °C (77.0 °F) and 4.2 days above 30.0 °C (86.0 °F) every year. During the 2003 European heat wave there were 14 consecutive days above 30 °C (86.0 °F) and 2 consecutive days when temperatures reached 38 °C (100 °F), leading to hundreds of heat-related deaths.[201] There was also a previous spell of 15 consecutive days above 32.2 °C (90.0 °F) in 1976 which also caused many heat related deaths.[202] The previous record high was 38 °C (100 °F) in August 1911 at the Greenwich station.[197] Droughts can also, occasionally, be a problem, especially in summer. Most recently in Summer 2018[203] and with much drier than average conditions prevailing from May to December.[204] However, the most consecutive days without rain was 73 days in the spring of 1893.[205]

Winters are generally cool with little temperature variation. Heavy snow is rare but snow usually happens at least once each winter. Spring and autumn can be pleasant. As a large city, London has a considerable urban heat island effect,[206] making the centre of London at times 5 °C (9 °F) warmer than the suburbs and outskirts. This can be seen below when comparing London Heathrow, 15 miles (24 km) west of London, with the London Weather Centre.[207]

Although London and the British Isles have a reputation of frequent rainfall, London's average of 602 millimetres (23.7 in) of precipitation annually actually makes it drier than the global average.[208] The absence of heavy winter rainfall leads to many climates around the Mediterranean having more annual precipitation than London.

Climate data for London, elevation: 25 m (82 ft), 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.2 (75.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.9 (100.2) |

38.1 (100.6) |

35.4 (95.7) |

29.9 (85.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.4 (45.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.1 (3.0) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.2 (2.17) |

40.9 (1.61) |

41.6 (1.64) |

43.7 (1.72) |

49.4 (1.94) |

45.1 (1.78) |

44.5 (1.75) |

49.5 (1.95) |

49.1 (1.93) |

68.5 (2.70) |

59.0 (2.32) |

55.2 (2.17) |

601.7 (23.68) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.1 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 109.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 61.5 | 77.9 | 114.6 | 168.7 | 198.5 | 204.3 | 212.0 | 204.7 | 149.3 | 116.5 | 72.6 | 52.0 | 1,632.6 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source 1: Met Office [209] Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute [210][211]For more station data, see Climate of London.[212] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Met Office [213] Weather Atlas [214] | |||||||||||||

Districts

London's vast urban area is often described using a set of district names, such as Mayfair, Southwark, Wembley and Whitechapel. These are either informal designations, reflect the names of villages that have been absorbed by sprawl, or are superseded administrative units such as parishes or former boroughs.

Such names have remained in use through tradition, each referring to a local area with its own distinctive character, but without official boundaries. Since 1965 Greater London has been divided into 32 London boroughs in addition to the ancient City of London.[215][216] The City of London is the main financial district,[217] and Canary Wharf has recently developed into a new financial and commercial hub in the Docklands to the east.

The West End is London's main entertainment and shopping district, attracting tourists.[218] West London includes expensive residential areas where properties can sell for tens of millions of pounds.[219] The average price for properties in Kensington and Chelsea is over £2 million with a similarly high outlay in most of central London.[220][221]

The East End is the area closest to the original Port of London, known for its high immigrant population, as well as for being one of the poorest areas in London.[222] The surrounding East London area saw much of London's early industrial development; now, brownfield sites throughout the area are being redeveloped as part of the Thames Gateway including the London Riverside and Lower Lea Valley, which was developed into the Olympic Park for the 2012 Olympics and Paralympics.[222]

Architecture

London's buildings are too diverse to be characterised by any particular architectural style, partly because of their varying ages. Many grand houses and public buildings, such as the National Gallery, are constructed from Portland stone. Some areas of the city, particularly those just west of the centre, are characterised by white stucco or whitewashed buildings. Few structures in central London pre-date the Great Fire of 1666, these being a few trace Roman remains, the Tower of London and a few scattered Tudor survivors in the city. Further out is, for example, the Tudor-period Hampton Court Palace, England's oldest surviving Tudor palace, built by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey c.1515.[223]

Part of the varied architectural heritage are the 17th-century churches by Wren, neoclassical financial institutions such as the Royal Exchange and the Bank of England, to the early 20th century Old Bailey and the 1960s Barbican Estate.

The disused – but soon to be rejuvenated – 1939 Battersea Power Station by the river in the south-west is a local landmark, while some railway termini are excellent examples of Victorian architecture, most notably St. Pancras and Paddington.[224] The density of London varies, with high employment density in the central area and Canary Wharf, high residential densities in inner London, and lower densities in Outer London.

The Monument in the City of London provides views of the surrounding area while commemorating the Great Fire of London, which originated nearby. Marble Arch and Wellington Arch, at the north and south ends of Park Lane, respectively, have royal connections, as do the Albert Memorial and Royal Albert Hall in Kensington. Nelson's Column is a nationally recognised monument in Trafalgar Square, one of the focal points of central London. Older buildings are mainly brick built, most commonly the yellow London stock brick or a warm orange-red variety, often decorated with carvings and white plaster mouldings.[225]

In the dense areas, most of the concentration is via medium- and high-rise buildings. London's skyscrapers, such as 30 St Mary Axe, Tower 42, the Broadgate Tower and One Canada Square, are mostly in the two financial districts, the City of London and Canary Wharf. High-rise development is restricted at certain sites if it would obstruct protected views of St Paul's Cathedral and other historic buildings. Nevertheless, there are a number of tall skyscrapers in central London (see Tall buildings in London), including the 95-storey Shard London Bridge, the tallest building in the United Kingdom.

Other notable modern buildings include City Hall in Southwark with its distinctive oval shape,[226] the Art Deco BBC Broadcasting House plus the Postmodernist British Library in Somers Town/Kings Cross and No 1 Poultry by James Stirling. What was formerly the Millennium Dome, by the Thames to the east of Canary Wharf, is now an entertainment venue called the O2 Arena.

Cityscape

Natural history

The London Natural History Society suggest that London is "one of the World's Greenest Cities" with more than 40 per cent green space or open water. They indicate that 2000 species of flowering plant have been found growing there and that the tidal Thames supports 120 species of fish.[227] They also state that over 60 species of bird nest in central London and that their members have recorded 47 species of butterfly, 1173 moths and more than 270 kinds of spider around London. London's wetland areas support nationally important populations of many water birds. London has 38 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs), two national nature reserves and 76 local nature reserves.[228]

Amphibians are common in the capital, including smooth newts living by the Tate Modern, and common frogs, common toads, palmate newts and great crested newts. On the other hand, native reptiles such as slowworms, common lizards, barred grass snakes and adders, are mostly only seen in Outer London.[229]

Among other inhabitants of London are 10,000 red foxes, so that there are now 16 foxes for every square mile (2.6 square kilometres) of London. These urban foxes are noticeably bolder than their country cousins, sharing the pavement with pedestrians and raising cubs in people's backyards. Foxes have even sneaked into the Houses of Parliament, where one was found asleep on a filing cabinet. Another broke into the grounds of Buckingham Palace, reportedly killing some of Queen Elizabeth II's prized pink flamingos. Generally, however, foxes and city folk appear to get along. A survey in 2001 by the London-based Mammal Society found that 80 per cent of 3,779 respondents who volunteered to keep a diary of garden mammal visits liked having them around. This sample cannot be taken to represent Londoners as a whole.[230][231]

Other mammals found in Greater London are hedgehog, brown rat, mice, rabbit, shrew, vole, and grey squirrel.[232] In wilder areas of Outer London, such as Epping Forest, a wide variety of mammals are found, including European hare, badger, field, bank and water vole, wood mouse, yellow-necked mouse, mole, shrew, and weasel, in addition to red fox, grey squirrel and hedgehog. A dead otter was found at The Highway, in Wapping, about a mile from the Tower Bridge, which would suggest that they have begun to move back after being absent a hundred years from the city.[233] Ten of England's eighteen species of bats have been recorded in Epping Forest: soprano, Nathusius' and common pipistrelles, common noctule, serotine, barbastelle, Daubenton's, brown long-eared, Natterer's and Leisler's.[234]

Among the strange sights seen in London have been a whale in the Thames,[235] while the BBC Two programme "Natural World: Unnatural History of London" shows feral pigeons using the London Underground to get around the city, a seal that takes fish from fishmongers outside Billingsgate Fish Market, and foxes that will "sit" if given sausages.[236]

Herds of red and fallow deer also roam freely within much of Richmond and Bushy Park. A cull takes place each November and February to ensure numbers can be sustained.[237] Epping Forest is also known for its fallow deer, which can frequently be seen in herds to the north of the Forest. A rare population of melanistic, black fallow deer is also maintained at the Deer Sanctuary near Theydon Bois. Muntjac deer, which escaped from deer parks at the turn of the twentieth century, are also found in the forest. While Londoners are accustomed to wildlife such as birds and foxes sharing the city, more recently urban deer have started becoming a regular feature, and whole herds of fallow deer come into residential areas at night to take advantage of London's green spaces.[238][239]

Demography

| 2011 United Kingdom Census[240] | |

|---|---|

| Country of birth | Population |

| 5,175,677 | |

| 262,247 | |

| 158,300 | |

| 129,807 | |

| 114,718 | |

| 112,457 | |

| 109,948 | |

| 87,467 | |

| 84,542 | |

| 66,654 | |

The 2011 census recorded that 2,998,264 people or 36.7% of London's population are foreign-born making London the city with the second largest immigrant population, behind New York City, in terms of absolute numbers. About 69% of children born in London in 2015 had at least one parent who was born abroad.[241] The table to the right shows the most common countries of birth of London residents. Note that some of the German-born population, in 18th position, are British citizens from birth born to parents serving in the British Armed Forces in Germany.[242]

With increasing industrialisation, London's population grew rapidly throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was for some time in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the most populous city in the world. Its population peaked at 8,615,245 in 1939 immediately before the outbreak of the Second World War, but had declined to 7,192,091 at the 2001 Census. However, the population then grew by just over a million between the 2001 and 2011 Censuses, to reach 8,173,941 in the latter enumeration.[243]

However, London's continuous urban area extends beyond the borders of Greater London and was home to 9,787,426 people in 2011,[56] while its wider metropolitan area has a population of between 12 and 14 million depending on the definition used.[244][245] According to Eurostat, London is the most populous city and metropolitan area of the European Union and the second most populous in Europe. During the period 1991–2001 a net 726,000 immigrants arrived in London.[246]

The region covers an area of 1,579 square kilometres (610 sq mi). The population density is 5,177 inhabitants per square kilometre (13,410/sq mi),[247] more than ten times that of any other British region.[248] In terms of population, London is the 19th largest city and the 18th largest metropolitan region.[249][250]

Age structure and median age

Children (aged younger than 14 years) constitute 21 percent of the population in Outer London, and 28 percent in Inner London; the age group aged between 15 and 24 years is 12 percent in both Outer and Inner London; those aged between 25 and 44 years are 31 percent in Outer London and 40 percent in Inner London; those aged between 45 and 64 years form 26 percent and 21 percent in Outer and Inner London respectively; while in Outer London those aged 65 and older are 13 percent, though in Inner London just 9 percent.[251]

The median age of London in 2017 is 36.5 years old.[252]

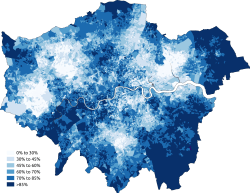

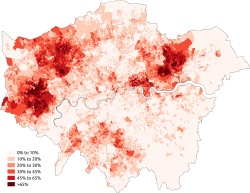

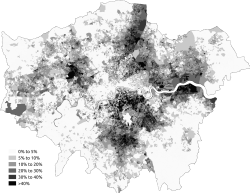

Ethnic groups

According to the Office for National Statistics, based on the 2011 Census estimates, 59.8 per cent of the 8,173,941 inhabitants of London were White, with 44.9 per cent White British, 2.2 per cent White Irish, 0.1 per cent gypsy/Irish traveller and 12.1 per cent classified as Other White.[253]

20.9 per cent of Londoners are of Asian and mixed-Asian descent. 19.7 per cent are of full Asian descent, with those of mixed-Asian heritage comprising 1.2 of the population. Indians account for 6.6 per cent of the population, followed by Pakistanis and Bangladeshis at 2.7 per cent each. Chinese peoples account for 1.5 per cent of the population, with Arabs comprising 1.3 per cent. A further 4.9 per cent are classified as "Other Asian".[253]

15.6 per cent of London's population are of Black and mixed-Black descent. 13.3 per cent are of full Black descent, with those of mixed-Black heritage comprising 2.3 per cent. Black Africans account for 7.0 per cent of London's population, with 4.2 per cent as Black Caribbean and 2.1 per cent as "Other Black". 5.0 per cent are of mixed race.[253]

As of 2007, Black and Asian children outnumbered White British children by about six to four in state schools across London.[254] Altogether at the 2011 census, of London's 1,624,768 population aged 0 to 15, 46.4 per cent were White, 19.8 per cent were Asian, 19 per cent were Black, 10.8 per cent were Mixed and 4 per cent represented another ethnic group.[255] In January 2005, a survey of London's ethnic and religious diversity claimed that there were more than 300 languages spoken in London and more than 50 non-indigenous communities with a population of more than 10,000.[256] Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that, in 2010, London's foreign-born population was 2,650,000 (33 per cent), up from 1,630,000 in 1997.

The 2011 census showed that 36.7 per cent of Greater London's population were born outside the UK.[257] A portion of the German-born population are likely to be British nationals born to parents serving in the British Armed Forces in Germany.[258] Estimates produced by the Office for National Statistics indicate that the five largest foreign-born groups living in London in the period July 2009 to June 2010 were those born in India, Poland, the Republic of Ireland, Bangladesh and Nigeria.[259]

Religion

According to the 2011 Census, the largest religious groupings are Christians (48.4 per cent), followed by those of no religion (20.7 per cent), Muslims (12.4 per cent), no response (8.5 per cent), Hindus (5.0 per cent), Jews (1.8 per cent), Sikhs (1.5 per cent), Buddhists (1.0 per cent) and other (0.6 per cent).

London has traditionally been Christian, and has a large number of churches, particularly in the City of London. The well-known St Paul's Cathedral in the City and Southwark Cathedral south of the river are Anglican administrative centres,[261] while the Archbishop of Canterbury, principal bishop of the Church of England and worldwide Anglican Communion, has his main residence at Lambeth Palace in the London Borough of Lambeth.[262]

Important national and royal ceremonies are shared between St Paul's and Westminster Abbey.[263] The Abbey is not to be confused with nearby Westminster Cathedral, which is the largest Roman Catholic cathedral in England and Wales.[264] Despite the prevalence of Anglican churches, observance is very low within the Anglican denomination. Church attendance continues on a long, slow, steady decline, according to Church of England statistics.[265]

London is also home to sizeable Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Jewish communities.

Notable mosques include the East London Mosque in Tower Hamlets, which is allowed to give the Islamic call to prayer through loudspeakers, the London Central Mosque on the edge of Regent's Park[266] and the Baitul Futuh of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Following the oil boom, increasing numbers of wealthy Middle-Eastern Arab Muslims have based themselves around Mayfair, Kensington, and Knightsbridge in West London.[267][268][269] There are large Bengali Muslim communities in the eastern boroughs of Tower Hamlets and Newham.[270]

Large Hindu communities are in the north-western boroughs of Harrow and Brent, the latter of which hosts what was, until 2006,[271] Europe's largest Hindu temple, Neasden Temple.[272] London is also home to 44 Hindu temples, including the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir London. There are Sikh communities in East and West London, particularly in Southall, home to one of the largest Sikh populations and the largest Sikh temple outside India.[273]

The majority of British Jews live in London, with significant Jewish communities in Stamford Hill, Stanmore, Golders Green, Finchley, Hampstead, Hendon and Edgware in North London. Bevis Marks Synagogue in the City of London is affiliated to London's historic Sephardic Jewish community. It is the only synagogue in Europe which has held regular services continuously for over 300 years. Stanmore and Canons Park Synagogue has the largest membership of any single Orthodox synagogue in the whole of Europe, overtaking Ilford synagogue (also in London) in 1998.[274] The community set up the London Jewish Forum in 2006 in response to the growing significance of devolved London Government.[275]

Accent

The accent of a 21st-century Londoner varies widely; what is becoming more and more common amongst the under-30s however is some fusion of Cockney with a whole array of ethnic accents, in particular Caribbean, which help to form an accent labelled Multicultural London English (MLE).[276] The other widely heard and spoken accent is RP (Received Pronunciation) in various forms, which can often be heard in the media and many of other traditional professions and beyond, although this accent is not limited to London and South East England, and can also be heard selectively throughout the whole UK amongst certain social groupings. Since the turn of the century the Cockney dialect is less common in the East End and has 'migrated' east to Havering and the county of Essex.[277][278]

Economy

London's gross regional product in 2018 was almost £500 billion, around a quarter of UK GDP.[280] London has five major business districts: the city, Westminster, Canary Wharf, Camden & Islington and Lambeth & Southwark. One way to get an idea of their relative importance is to look at relative amounts of office space: Greater London had 27 million m2 of office space in 2001, and the City contains the most space, with 8 million m2 of office space. London has some of the highest real estate prices in the world.[281][282] London is the world's most expensive office market for the last three years according to world property journal (2015) report.[283] As of 2015 the residential property in London is worth $2.2 trillion – same value as that of Brazil's annual GDP.[284] The city has the highest property prices of any European city according to the Office for National Statistics and the European Office of Statistics.[285] On average the price per square metre in central London is €24,252 (April 2014). This is higher than the property prices in other G8 European capital cities; Berlin €3,306, Rome €6,188 and Paris €11,229.[286]

The City of London

London's finance industry is based in the City of London and Canary Wharf, the two major business districts in London. London is one of the pre-eminent financial centres of the world as the most important location for international finance.[287][288] London took over as a major financial centre shortly after 1795 when the Dutch Republic collapsed before the Napoleonic armies. For many bankers established in Amsterdam (e.g. Hope, Baring), this was only time to move to London. The London financial elite was strengthened by a strong Jewish community from all over Europe capable of mastering the most sophisticated financial tools of the time.[110] This unique concentration of talents accelerated the transition from the Commercial Revolution to the Industrial Revolution. By the end of the 19th century, Britain was the wealthiest of all nations, and London a leading financial centre. Still, as of 2016 London tops the world rankings on the Global Financial Centres Index (GFCI),[289] and it ranked second in A.T. Kearney's 2018 Global Cities Index.[290]

London's largest industry is finance, and its financial exports make it a large contributor to the UK's balance of payments. Around 325,000 people were employed in financial services in London until mid-2007. London has over 480 overseas banks, more than any other city in the world. It is also the world's biggest currency trading centre, accounting for some 37 per cent of the $5.1 trillion average daily volume, according to the BIS.[291] Over 85 per cent (3.2 million) of the employed population of greater London works in the services industries. Because of its prominent global role, London's economy had been affected by the financial crisis of 2007–2008. However, by 2010 the city has recovered; put in place new regulatory powers, proceeded to regain lost ground and re-established London's economic dominance.[292] Along with professional services headquarters, the City of London is home to the Bank of England, London Stock Exchange, and Lloyd's of London insurance market.

Over half of the UK's top 100 listed companies (the FTSE 100) and over 100 of Europe's 500 largest companies have their headquarters in central London. Over 70 per cent of the FTSE 100 are within London's metropolitan area, and 75 per cent of Fortune 500 companies have offices in London.[293]

Media and technology

Media companies are concentrated in London and the media distribution industry is London's second most competitive sector.[294] The BBC is a significant employer, while other broadcasters also have headquarters around the city. Many national newspapers are edited in London. London is a major retail centre and in 2010 had the highest non-food retail sales of any city in the world, with a total spend of around £64.2 billion.[295] The Port of London is the second-largest in the United Kingdom, handling 45 million tonnes of cargo each year.[296]

A growing number of technology companies are based in London notably in East London Tech City, also known as Silicon Roundabout. In April 2014, the city was among the first to receive a geoTLD.[297] In February 2014 London was ranked as the European City of the Future[298] in the 2014/15 list by FDi Magazine.[299]

The gas and electricity distribution networks that manage and operate the towers, cables and pressure systems that deliver energy to consumers across the city are managed by National Grid plc, SGN[300] and UK Power Networks.[301]

Tourism

London is one of the leading tourist destinations in the world and in 2015 was ranked as the most visited city in the world with over 65 million visits.[302][303] It is also the top city in the world by visitor cross-border spending, estimated at US$20.23 billion in 2015.[304] Tourism is one of London's prime industries, employing the equivalent of 350,000 full-time workers in 2003,[305] and the city accounts for 54% of all inbound visitor spending in the UK.[306] As of 2016 London was the world top city destination as ranked by TripAdvisor users.[307]

In 2015 the top most-visited attractions in the UK were all in London. The top 10 most visited attractions were: (with visits per venue)[308]

- The British Museum: 6,820,686

- The National Gallery: 5,908,254

- The Natural History Museum (South Kensington): 5,284,023

- The Southbank Centre: 5,102,883

- Tate Modern: 4,712,581

- The Victoria and Albert Museum (South Kensington): 3,432,325

- The Science Museum: 3,356,212

- Somerset House: 3,235,104

- The Tower of London: 2,785,249

- The National Portrait Gallery: 2,145,486

The number of hotel rooms in London in 2015 stood at 138,769, and is expected to grow over the years.[309]

Transport

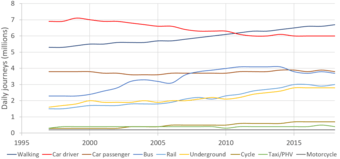

Transport is one of the four main areas of policy administered by the Mayor of London,[311] however the mayor's financial control does not extend to the longer distance rail network that enters London. In 2007 he assumed responsibility for some local lines, which now form the London Overground network, adding to the existing responsibility for the London Underground, trams and buses. The public transport network is administered by Transport for London (TfL).

The lines that formed the London Underground, as well as trams and buses, became part of an integrated transport system in 1933 when the London Passenger Transport Board or London Transport was created. Transport for London is now the statutory corporation responsible for most aspects of the transport system in Greater London, and is run by a board and a commissioner appointed by the Mayor of London.[312]

Aviation

London is a major international air transport hub with the busiest city airspace in the world. Eight airports use the word London in their name, but most traffic passes through six of these. Additionally, various other airports also serve London, catering primarily to general aviation flights.

- London Heathrow Airport, in Hillingdon, West London, was for many years the busiest airport in the world for international traffic, and is the major hub of the nation's flag carrier, British Airways.[313] In March 2008 its fifth terminal was opened.[314] In 2014, Dubai gained from Heathrow the leading position in terms of international passenger traffic.[315]

- London Gatwick Airport,[316] south of London in West Sussex, handles flights to more destinations than any other UK airport[317] and is the main base of easyJet,[318] the UK's largest airline by number of passengers.[319]

- London Stansted Airport,[320] north-east of London in Essex, has flights that serve the greatest number of European destinations of any UK airport[321] and is the main base of Ryanair,[322] the world's largest international airline by number of international passengers.[323]

- London Luton Airport, to the north of London in Bedfordshire, is used by several budget airlines for short-haul flights.[324]

- London City Airport, the most central airport and the one with the shortest runway, in Newham, East London, is focused on business travellers, with a mixture of full-service short-haul scheduled flights and considerable business jet traffic.[325]

- London Southend Airport, east of London in Essex, is a smaller, regional airport that caters for short-haul flights on a limited, though growing, number of airlines.[326] In 2017, international passengers made up over 95% of the total at Southend, the highest proportion of any London airport.[327]

Rail

Underground and DLR

The London Underground, commonly referred to as the Tube, is the oldest[328] and third longest[329] metro system in the world. The system serves 270 stations[330] and was formed from several private companies, including the world's first underground electric line, the City and South London Railway.[331] It dates from 1863.[332]

Over four million journeys are made every day on the Underground network, over 1 billion each year.[333] An investment programme is attempting to reduce congestion and improve reliability, including £6.5 billion (€7.7 billion) spent before the 2012 Summer Olympics.[334] The Docklands Light Railway (DLR), which opened in 1987, is a second, more local metro system using smaller and lighter tram-type vehicles that serve the Docklands, Greenwich and Lewisham.

Suburban

There are more than 360 railway stations in the London Travelcard Zones on an extensive above-ground suburban railway network. South London, particularly, has a high concentration of railways as it has fewer Underground lines. Most rail lines terminate around the centre of London, running into eighteen terminal stations, with the exception of the Thameslink trains connecting Bedford in the north and Brighton in the south via Luton and Gatwick airports.[335] London has Britain's busiest station by number of passengers – Waterloo, with over 184 million people using the interchange station complex (which includes Waterloo East station) each year.[336][337] Clapham Junction is the busiest station in Europe by the number of trains passing.

With the need for more rail capacity in London, Crossrail is expected to open in 2021.[338] It will be a new railway line running east to west through London and into the Home Counties with a branch to Heathrow Airport.[339] It is Europe's biggest construction project, with a £15 billion projected cost.[340][341]

Inter-city and international

London is the centre of the National Rail network, with 70 per cent of rail journeys starting or ending in London.[342] Like suburban rail services, regional and inter-city trains depart from several termini around the city centre, linking London with the rest of Britain including Birmingham, Brighton, Bristol, Cambridge, Cardiff, Chester, Derby, Holyhead (for Dublin), Edinburgh, Exeter, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, Nottingham, Manchester, Newcastle upon Tyne, Norwich, Reading, Sheffield, York.

Some international railway services to Continental Europe were operated during the 20th century as boat trains, such as the Admiraal de Ruijter to Amsterdam and the Night Ferry to Paris and Brussels. The opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 connected London directly to the continental rail network, allowing Eurostar services to begin. Since 2007, high-speed trains link St. Pancras International with Lille, Calais, Paris, Disneyland Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and other European tourist destinations via the High Speed 1 rail link and the Channel Tunnel.[343] The first high-speed domestic trains started in June 2009 linking Kent to London.[344] There are plans for a second high speed line linking London to the Midlands, North West England, and Yorkshire.

Freight

Although rail freight levels are far down compared to their height, significant quantities of cargo are also carried into and out of London by rail; chiefly building materials and landfill waste.[345] As a major hub of the British railway network, London's tracks also carry large amounts of freight for the other regions, such as container freight from the Channel Tunnel and English Channel ports, and nuclear waste for reprocessing at Sellafield.[345]

Buses, coaches and trams

_Go-Ahead_London_New_Routemaster_(20929161801).jpg)

London's bus network runs 24 hours a day, with about 8,500 buses, more than 700 bus routes and around 19,500 bus stops.[346] In 2013, the network had more than 2 billion commuter trips per year, more than the Underground.[346] Around £850 million is taken in revenue each year. London has the largest wheelchair-accessible network in the world[347] and, from the third quarter of 2007, became more accessible to hearing and visually impaired passengers as audio-visual announcements were introduced.

London's coach hub is based at Victoria Coach Station. in an Art Deco building opened in 1932. The coach station was initially run by a group of coach companies under the name of London Coastal Coaches however in 1970 the service and station were part of the nationalisation of the country's coach services becoming part of the National Bus Company. In 1988, the coach station was purchased by London Transport which then became Transport for London. Victoria Coach Station has weekly passenger numbers of over 200000 providing services across the UK and Europe.[348]

London has a modern tram network, known as Tramlink, centred on Croydon in South London. The network has 39 stops and four routes, and carried 28 million people in 2013.[349] Since June 2008, Transport for London has completely owned Tramlink.[350]

Cable car

London's first only cable car is the Emirates Air Line, which opened in June 2012. The cable car crosses the River Thames, and links Greenwich Peninsula and the Royal Docks in the east of the city. It is integrated with London's Oyster Card ticketing system, although special fares are charged. It cost £60 million to build and carries more than 3,500 passengers every day. Similar to the Santander Cycles bike hire scheme, the cable car is sponsored in a 10-year deal by the airline Emirates.

Cycling

In the Greater London Area, around 650,000 people use a bike everyday.[351] But out of a total population of around 8.8 million,[352] this means that just around 7% of Greater London's population use a bike on an average day.[353] This relatively low percentage of bicycle users may be due to the poor investments for cycling in London of about £110 million per year,[354] equating to around £12 per person, which can be compared to £22 in the Netherlands.[355]

Cycling has become an increasingly popular way to get around London. The launch of a cycle hire scheme in July 2010 was successful and generally well received.

Port and river boats

The Port of London, once the largest in the world, is now only the second-largest in the United Kingdom, handling 45 million tonnes of cargo each year as of 2009.[296] Most of this cargo passes through the Port of Tilbury, outside the boundary of Greater London.[296]

London has river boat services on the Thames known as Thames Clippers, which offers both commuter and tourist boat services.[356] These run every 20 minutes between Embankment Pier and North Greenwich Pier. The Woolwich Ferry, with 2.5 million passengers every year,[357] is a frequent service linking the North and South Circular Roads.

Roads

Although the majority of journeys in central London are made by public transport, car travel is common in the suburbs. The inner ring road (around the city centre), the North and South Circular roads (just within the suburbs), and the outer orbital motorway (the M25, just outside the built-up area in most places) encircle the city and are intersected by a number of busy radial routes—but very few motorways penetrate into inner London. A plan for a comprehensive network of motorways throughout the city (the Ringways Plan) was prepared in the 1960s but was mostly cancelled in the early 1970s.[358] The M25 is the second-longest ring-road motorway in Europe at 117 mi (188 km) long.[359] The A1 and M1 connect London to Leeds, and Newcastle and Edinburgh.

London is notorious for its traffic congestion; in 2009, the average speed of a car in the rush hour was recorded at 10.6 mph (17.1 km/h).[360]

In 2003, a congestion charge was introduced to reduce traffic volumes in the city centre. With a few exceptions, motorists are required to pay to drive within a defined zone encompassing much of central London.[361] Motorists who are residents of the defined zone can buy a greatly reduced season pass.[362][363] The London government initially expected the Congestion Charge Zone to increase daily peak period Underground and bus users, reduce road traffic, increase traffic speeds, and reduce queues;[364] however, the increase in private for hire vehicles has affected these expectations. Over the course of several years, the average number of cars entering the centre of London on a weekday was reduced from 195,000 to 125,000 cars – a 35-per-cent reduction of vehicles driven per day.[365][366]

Education

Tertiary education

London is a major global centre of higher education teaching and research and has the largest concentration of higher education institutes in Europe.[48] According to the QS World University Rankings 2015/16, London has the greatest concentration of top class universities in the world[367][368] and its international student population of around 110,000 is larger than any other city in the world.[369] A 2014 PricewaterhouseCoopers report termed London the global capital of higher education.[370]

A number of world-leading education institutions are based in London. In the 2014/15 QS World University Rankings, Imperial College London is ranked joint-second in the world, University College London (UCL) is ranked fifth, and King's College London (KCL) is ranked 16th.[371] The London School of Economics has been described as the world's leading social science institution for both teaching and research.[372] The London Business School is considered one of the world's leading business schools and in 2015 its MBA programme was ranked second-best in the world by the Financial Times.[373] The city is also home to three of the world's top ten performing arts schools (as ranked by the 2020 QS World University Rankings[374]): the Royal College of Music (ranking 2nd in the world), the Royal Academy of Music (ranking 4th) and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama (ranking 6th).

With 178,735 students in London[375] and around 48,000 in University of London Worldwide,[376] the federal University of London is the largest contact teaching university in the UK.[377] It includes five multi-faculty universities – City, King's College London, Queen Mary, Royal Holloway and UCL – and a number of smaller and more specialised institutions including Birkbeck, the Courtauld Institute of Art, Goldsmiths, the London Business School, the London School of Economics, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the Royal Academy of Music, the Central School of Speech and Drama, the Royal Veterinary College and the School of Oriental and African Studies.[378] Members of the University of London have their own admissions procedures, and most award their own degrees.

A number of universities in London are outside the University of London system, including Brunel University, Imperial College London[note 7], Kingston University, London Metropolitan University,[379] University of East London, University of West London, University of Westminster, London South Bank University, Middlesex University, and University of the Arts London (the largest university of art, design, fashion, communication and the performing arts in Europe).[380] In addition there are three international universities in London – Regent's University London, Richmond, The American International University in London and Schiller International University.

London is home to five major medical schools – Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry (part of Queen Mary), King's College London School of Medicine (the largest medical school in Europe), Imperial College School of Medicine, UCL Medical School and St George's, University of London – and has many affiliated teaching hospitals. It is also a major centre for biomedical research, and three of the UK's eight academic health science centres are based in the city – Imperial College Healthcare, King's Health Partners and UCL Partners (the largest such centre in Europe).[381] Additionally, many biomedical and biotechnology spin out companies from these research institutions are based around the city, most prominently in White City.

There are a number of business schools in London, including the London School of Business and Finance, Cass Business School (part of City University London), Hult International Business School, ESCP Europe, European Business School London, Imperial College Business School, the London Business School and the UCL School of Management. London is also home to many specialist arts education institutions, including the Academy of Live and Recorded Arts, Central School of Ballet, LAMDA, London College of Contemporary Arts (LCCA), London Contemporary Dance School, National Centre for Circus Arts, RADA, Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance, the Royal College of Art and Trinity Laban.

Primary and secondary education

The majority of primary and secondary schools and further-education colleges in London are controlled by the London boroughs or otherwise state-funded; leading examples include Ashbourne College, Bethnal Green Academy, Brampton Manor Academy, City and Islington College, City of Westminster College, David Game College, Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College, Leyton Sixth Form College, London Academy of Excellence, Tower Hamlets College, and Newham Collegiate Sixth Form Centre. There are also a number of private schools and colleges in London, some old and famous, such as City of London School, Harrow, St Paul's School, Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School, University College School, The John Lyon School, Highgate School and Westminster School.

Culture

Leisure and entertainment

Leisure is a major part of the London economy, with a 2003 report attributing a quarter of the entire UK leisure economy to London[382] at 25.6 events per 1000 people.[383] Globally the city is amongst the big four fashion capitals of the world, and according to official statistics, London is the world's third-busiest film production centre, presents more live comedy than any other city,[384] and has the biggest theatre audience of any city in the world.[385]

Within the City of Westminster in London, the entertainment district of the West End has its focus around Leicester Square, where London and world film premieres are held, and Piccadilly Circus, with its giant electronic advertisements.[386] London's theatre district is here, as are many cinemas, bars, clubs, and restaurants, including the city's Chinatown district (in Soho), and just to the east is Covent Garden, an area housing speciality shops. The city is the home of Andrew Lloyd Webber, whose musicals have dominated the West End theatre since the late 20th century.[387] The United Kingdom's Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, Royal Opera, and English National Opera are based in London and perform at the Royal Opera House, the London Coliseum, Sadler's Wells Theatre, and the Royal Albert Hall, as well as touring the country.[388]

Islington's 1 mile (1.6 km) long Upper Street, extending northwards from Angel, has more bars and restaurants than any other street in the United Kingdom.[389] Europe's busiest shopping area is Oxford Street, a shopping street nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) long, making it the longest shopping street in the UK. Oxford Street is home to vast numbers of retailers and department stores, including the world-famous Selfridges flagship store.[390] Knightsbridge, home to the equally renowned Harrods department store, lies to the south-west.

London is home to designers Vivienne Westwood, Galliano, Stella McCartney, Manolo Blahnik, and Jimmy Choo, among others; its renowned art and fashion schools make it an international centre of fashion alongside Paris, Milan, and New York City. London offers a great variety of cuisine as a result of its ethnically diverse population. Gastronomic centres include the Bangladeshi restaurants of Brick Lane and the Chinese restaurants of Chinatown.[391]