Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (informally abbreviated to PM) is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister directs both the executive and the legislature, and together with their Cabinet is accountable to the monarch, to Parliament, to their party, and ultimately to the electorate, for the government's policies and actions.

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Government of the United Kingdom Parliament of the United Kingdom Prime Minister's Office Cabinet Office | |

| Style | Prime Minister (informal) The Right Honourable (UK and Commonwealth) His Excellency[1] (international) |

| Status | Head of Government |

| Member of | |

| Reports to | House of Commons and the Monarch |

| Residence |

|

| Seat | Westminster |

| Nominator | Political parties |

| Appointer | The Crown The incumbent monarch appoints the person who commands the confidence of the House of Commons |

| Term length | At Her Majesty's Pleasure While commanding the confidence of the majority of the House of Commons. No term limits are imposed on the office. |

| Inaugural holder | Sir Robert Walpole |

| Formation | 3 April 1721 |

| Salary | £158,754 per annum[2][3] (including £79,468 MP salary)[4] |

| Website | www |

The office of Prime Minister is not established by any statute or constitutional document but exists only by long-established convention, whereby the reigning monarch appoints as prime minister the person most likely to command the confidence of the House of Commons;[5] this individual is typically the leader of the political party or coalition of parties that holds the largest number of seats in that chamber. The position of Prime Minister was not created; it evolved slowly and organically over three hundred years due to numerous Acts of Parliament, political developments, and accidents of history. The office is therefore best understood from a historical perspective. The origins of the position are found in constitutional changes that occurred during the Revolutionary Settlement (1688–1720) and the resulting shift of political power from the Sovereign to Parliament.[6] Although the sovereign was not stripped of the ancient prerogative powers and legally remained the head of government, politically it gradually became necessary for him or her to govern through a prime minister who could command a majority in Parliament.

By the 1830s, the Westminster system of government (or cabinet government) had emerged; the prime minister had become primus inter pares or the first among equals in the Cabinet and the head of government in the United Kingdom. The political position of Prime Minister was enhanced by the development of modern political parties, the introduction of mass communication and photography. By the start of the 20th century the modern premiership had emerged; the office had become the pre-eminent position in the constitutional hierarchy vis-à-vis the Sovereign, Parliament and Cabinet.

Prior to 1902, the prime minister sometimes came from the House of Lords, provided that his government could form a majority in the Commons. However as the power of the aristocracy waned during the 19th century the convention developed that the prime minister should always sit as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the lower house, making them answerable only to the Commons in Parliament. As leader of the House of Commons, the prime minister's authority was further enhanced by the Parliament Act 1911 which marginalised the influence of the House of Lords in the law-making process.

The prime minister is ex officio also First Lord of the Treasury and Minister for the Civil Service. Indeed, certain privileges, such as residency of 10 Downing Street, are accorded to prime ministers by virtue of their position as First Lord of the Treasury.

The status and executive powers of the British prime minister means that the incumbent is consistently ranked as one of the most powerful democratically elected leaders in the world.

Authority

The prime minister is the head of the United Kingdom government.[7] As such, the modern prime minister leads the Cabinet (the Executive). In addition, the prime minister leads a major political party and generally commands a majority in the House of Commons (the lower House of the legislature). The incumbent wields both significant legislative and executive powers. Under the British system, there is a unity of powers rather than separation.[8] In the House of Commons, the prime minister guides the law-making process with the goal of enacting the legislative agenda of their political party. In an executive capacity, the prime minister appoints (and may dismiss) all other Cabinet members and ministers, and co-ordinates the policies and activities of all government departments, and the staff of the Civil Service. The prime minister also acts as the public "face" and "voice" of Her Majesty's Government, both at home and abroad. Solely upon the advice of the prime minister, the Sovereign exercises many statutory and prerogative powers, including high judicial, political, official and Church of England ecclesiastical appointments; the conferral of peerages and some knighthoods, decorations and other important honours.[9]

Constitutional background

The British system of government is based on an uncodified constitution, meaning that it is not set out in any single document.[10] The British constitution consists of many documents and most importantly for the evolution of the office of the prime minister, it is based on customs known as constitutional conventions that became accepted practice. In 1928, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith described this characteristic of the British constitution in his memoirs:

In this country we live ... under an unwritten Constitution. It is true that we have on the Statute-book great instruments like Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the Bill of Rights which define and secure many of our rights and privileges; but the great bulk of our constitutional liberties and ... our constitutional practices do not derive their validity and sanction from any Bill which has received the formal assent of the King, Lords and Commons. They rest on usage, custom, convention, often of slow growth in their early stages, not always uniform, but which in the course of time received universal observance and respect.[11]

The relationships between the prime minister and the sovereign, Parliament and Cabinet are defined largely by these unwritten conventions of the constitution. Many of the prime minister's executive and legislative powers are actually royal prerogatives which are still formally vested in the sovereign, who remains the head of state.[12] Despite its growing dominance in the constitutional hierarchy, the premiership was given little formal recognition until the 20th century; the legal fiction was maintained that the Sovereign still governed directly. The position was first mentioned in statute only in 1917, in the schedule of the Chequers Estate Act. Increasingly during the 20th century, the office and role of Prime Minister featured in statute law and official documents; however, the prime minister's powers and relationships with other institutions still largely continue to derive from ancient royal prerogatives and historic and modern constitutional conventions. Prime ministers continue to hold the position of First Lord of the Treasury and, since November 1968, that of Minister for the Civil Service, the latter giving them authority over the civil service.

Under this arrangement, Britain might appear to have two executives: the prime minister and the sovereign. The concept of "the Crown" resolves this paradox.[13] The Crown symbolises the state's authority to govern: to make laws and execute them, impose taxes and collect them, declare war and make peace. Before the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688, the sovereign exclusively wielded the powers of the Crown; afterwards, Parliament gradually forced monarchs to assume a neutral political position. Parliament has effectively dispersed the powers of the Crown, entrusting its authority to responsible ministers (the prime minister and Cabinet), accountable for their policies and actions to Parliament, in particular the elected House of Commons.

Although many of the sovereign's prerogative powers are still legally intact,[note 1] constitutional conventions have removed the monarch from day-to-day governance, with ministers exercising the royal prerogatives, leaving the monarch in practice with three constitutional rights: to be kept informed, to advise and to warn.[14][15]

Foundations

Revolutionary Settlement

Because the premiership was not intentionally created, there is no exact date when its evolution began. A meaningful starting point, however, is 1688–89 when James II fled England and the Parliament of England confirmed William III and Mary II as joint constitutional monarchs, enacting legislation that limited their authority and that of their successors: the Bill of Rights (1689), the Mutiny Bill (1689), the Triennial Bill (1694), the Treason Act (1696) and the Act of Settlement (1701).[16] Known collectively as the Revolutionary Settlement, these acts transformed the constitution, shifting the balance of power from the Sovereign to Parliament. Once the office of Prime Minister was created, they also provided the basis for its evolution.

Treasury Bench

The Revolutionary Settlement gave the Commons control over finances and legislation and changed the relationship between the Executive and the Legislature. For want of money, sovereigns had to summon Parliament annually and could no longer dissolve or prorogue it without its advice and consent. Parliament became a permanent feature of political life.[17] The veto fell into disuse because sovereigns feared that if they denied legislation, Parliament would deny them money. No sovereign has denied royal assent since Queen Anne vetoed the Scottish Militia Bill in 1708.[18]

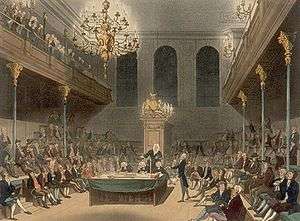

Treasury officials and other department heads were drawn into Parliament serving as liaisons between it and the sovereign. Ministers had to present the government's policies, and negotiate with Members to gain the support of the majority; they had to explain the government's financial needs, suggest ways of meeting them and give an account of how money had been spent. The Sovereign's representatives attended Commons sessions so regularly that they were given reserved seats at the front, known as the Treasury Bench. This is the beginning of "unity of powers": the sovereign's ministers (the Executive) became leading members of Parliament (the Legislature). Today, the prime minister (First Lord of the Treasury), the Chancellor of the Exchequer (responsible for The Budget) and other senior members of the Cabinet sit on the Treasury bench and present policies in much the same way Ministers did late in the 17th century.

Standing Order 66

After the Revolution, there was a constant threat that non-government members of Parliament would ruin the country's finances by proposing ill-considered money bills. Vying for control to avoid chaos, the Crown's Ministers gained an advantage in 1706, when the Commons informally declared, "That this House will receive no petition for any sum of money relating to public Service, but what is recommended from the Crown." On 11 June 1713, this non-binding rule became Standing Order 66: that "the Commons would not vote money for any purpose, except on a motion of a Minister of the Crown." Standing Order 66 remains in effect today (though renumbered as no. 48),[19] essentially unchanged for more than three hundred years.[20]

Empowering ministers with sole financial initiative had an immediate and lasting impact. Apart from achieving its intended purpose – to stabilise the budgetary process – it gave the Crown a leadership role in the Commons; and, the Lord Treasurer assumed a leading position among ministers.

The power of financial initiative was not, however, absolute. Only Ministers might initiate money bills, but Parliament now reviewed and consented to them. Standing Order 66 therefore represents the beginnings of Ministerial responsibility and accountability.[21]

The term "Prime Minister" appears at this time as an unofficial title for the leader of the government, usually the Head of the Treasury.[22] Jonathan Swift, for example, wrote that in 1713 there had been "those who are now commonly called Prime Minister among us", referring to Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin and Robert Harley, Queen Anne's Lord Treasurers and chief ministers.[23] Since 1721, every head of the Sovereign's government – with one exception in the 18th century (William Pitt the Elder) and one in the 19th (Lord Salisbury) – has been First Lord of the Treasury.

Beginnings of the prime minister's party leadership

Political parties first appeared during the Exclusion Crisis of 1678–1681. The Whigs, who believed in limited monarchy, wanted to exclude James, Duke of York, from succeeding to the throne because he was a Roman Catholic. The Tories, who believed in the "Divine Right of Kings", defended James's hereditary claim.

Political parties were not well organised or disciplined in the 17th century. They were more like factions, with "members" drifting in and out, collaborating temporarily on issues when it was to their advantage, then disbanding when it was not. A major deterrent to the development of opposing parties was the idea that there could only be one "King's Party" and to oppose it would be disloyal or even treasonous. This idea lingered throughout the 18th century. Nevertheless it became possible at the end of the 17th century to identify Parliaments and Ministries as being either "Whig" or "Tory" in composition.

Cabinet

The modern prime minister is also the leader of the Cabinet. A convention of the constitution, the modern Cabinet is a group of ministers who formulate policies.[24] As the political heads of government departments Cabinet Ministers ensure that policies are carried out by permanent civil servants. Although the modern prime minister selects ministers, appointment still rests with the sovereign.[25] With the prime minister as its leader, the Cabinet forms the executive branch of government.[note 2]

The term "Cabinet" first appears after the Revolutionary Settlement to describe those ministers who conferred privately with the sovereign. The growth of the Cabinet met with widespread complaint and opposition because its meetings were often held in secret and it excluded the ancient Privy Council (of which the Cabinet is formally a committee) from the sovereign's circle of advisers, reducing it to an honorary body.[27] The early Cabinet, like that of today, included the Treasurer and other department heads who sat on the Treasury bench. However, it might also include individuals who were not members of Parliament such as household officers (e.g. the Master of the Horse) and members of the royal family. The exclusion of non-members of Parliament from the Cabinet was essential to the development of ministerial accountability and responsibility.

Both William and Anne appointed and dismissed Cabinet members, attended meetings, made decisions, and followed up on actions. Relieving the Sovereign of these responsibilities and gaining control over the Cabinet's composition was an essential part of evolution of the Premiership. This process began after the Hanoverian Succession. Although George I (1714–1727) attended Cabinet meetings at first, after 1717 he withdrew because he did not speak fluent English and was bored with the discussions. George II (1727–1760) occasionally presided at Cabinet meetings but his successor, George III (1760–1820), is known to have attended only two during his 60-year reign. Thus, the convention that sovereigns do not attend Cabinet meetings was established primarily through royal indifference to the everyday tasks of governance. The prime minister became responsible for calling meetings, presiding, taking notes, and reporting to the Sovereign. These simple executive tasks naturally gave the prime minister ascendancy over his Cabinet colleagues.[28]

Although the first three Hanoverians rarely attended Cabinet meetings they insisted on their prerogatives to appoint and dismiss ministers and to direct policy even if from outside the Cabinet. It was not until late in the 18th century that prime ministers gained control over Cabinet composition (see section Emergence of Cabinet Government below).

"One Party Government"

British governments (or ministries) are generally formed by one party. The prime minister and Cabinet are usually all members of the same political party, almost always the one that has a majority of seats in the House of Commons. Coalition governments (a ministry that consists of representatives from two or more parties) and minority governments (a one-party ministry formed by a party that does not command a majority in the Commons) were relatively rare before the 2010 election, since 2010 there has been both a coalition and minority government. "One party government", as this system is sometimes called, has been the general rule for almost three hundred years.

Early in his reign, William III (1689–1702) preferred "mixed ministries" (or coalitions) consisting of both Tories and Whigs. William thought this composition would dilute the power of any one party and also give him the benefit of differing points of view. However, this approach did not work well because the members could not agree on a leader or on policies, and often worked at odds with each other.

In 1697, William formed a homogeneous Whig ministry. Known as the Junto, this government is often cited as the first true Cabinet because its members were all Whigs, reflecting the majority composition of the Commons.[29]

Anne (1702–1714) followed this pattern but preferred Tory Cabinets. This approach worked well as long as Parliament was also predominantly Tory. However, in 1708, when the Whigs obtained a majority, Anne did not call on them to form a government, refusing to accept the idea that politicians could force themselves on her merely because their party had a majority.[30] She never parted with an entire Ministry or accepted an entirely new one regardless of the results of an election. Anne preferred to retain a minority government rather than be dictated to by Parliament. Consequently, her chief ministers Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin and Robert Harley, who were called "Prime Minister" by some, had difficulty executing policy in the face of a hostile Parliament.[31][32]

William's and Anne's experiments with the political composition of the Cabinet illustrated the strengths of one party government and the weaknesses of coalition and minority governments. Nevertheless, it was not until the 1830s that the constitutional convention was established that the Sovereign must select the prime minister (and Cabinet) from the party whose views reflect those of the majority in Parliament. Since then, most ministries have reflected this one party rule.

Despite the "one party" convention, prime ministers may still be called upon to lead either minority or coalition governments. A minority government may be formed as a result of a "hung parliament" in which no single party commands a majority in the House of Commons after a general election or the death, resignation or defection of existing members. By convention, the serving prime minister is given the first opportunity to reach agreements that will allow them to survive a vote of confidence in the House and continue to govern. Until 2017, the last minority government was led by Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson for eight months after the February 1974 general election produced a hung parliament. In the October 1974 general election, the Labour Party gained 18 seats, giving Wilson a majority of three.

A hung parliament may also lead to the formation of a coalition government in which two or more parties negotiate a joint programme to command a majority in the Commons. Coalitions have also been formed during times of national crisis such as war. Under such circumstances, the parties agree to temporarily set aside their political differences and to unite to face the national crisis. Coalitions are rare: since 1721, there have been fewer than a dozen.

When the general election of 2010 produced a hung parliament, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties agreed to form the Cameron–Clegg coalition, the first coalition in seventy years. The previous coalition in the UK before 2010 was led by Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill during most of the Second World War, from May 1940 to May 1945. Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, served as Deputy Prime Minister.[33] After the general election of 2015, the nation returned to one party government after the Tories won an outright majority.

Treasury Commission

The premiership is still largely a convention of the constitution; its legal authority is derived primarily from the fact that the prime minister is also First Lord of the Treasury. The connection of these two offices – one a convention, the other a legal office – began with the Hanoverian succession in 1714.

When George I succeeded to the British throne in 1714, his German ministers advised him to leave the office of Lord High Treasurer vacant because those who had held it in recent years had grown overly powerful, in effect, replacing the sovereign as head of the government. They also feared that a Lord High Treasurer would undermine their own influence with the new king. They therefore suggested that he place the office in "commission", meaning that a committee of five ministers would perform its functions together. Theoretically, this dilution of authority would prevent any one of them from presuming to be the head of the government. The king agreed and created the Treasury Commission consisting of the First Lord of the Treasury, the Second Lord, and three Junior Lords.

No one has been appointed Lord High Treasurer since 1714; it has remained in commission for three hundred years. The Treasury Commission ceased to meet late in the 18th century but has survived, albeit with very different functions: the First Lord of the Treasury is now the prime minister, the Second Lord is the Chancellor of the Exchequer (and actually in charge of the Treasury), and the Junior Lords are government Whips maintaining party discipline in the House of Commons; they no longer have any duties related to the Treasury, though when subordinate legislation requires the consent of the Treasury it is still two of the Junior Lords who sign on its behalf.[note 3][34]

Early prime ministers

"First" prime minister

Since the office evolved rather than being instantly created, it may not be totally clear-cut who the first prime minister was. However, this appellation is traditionally given to Sir Robert Walpole, who became First Lord of the Treasury of Great Britain in 1721.

In 1720, the South Sea Company, created to trade in cotton, agricultural goods and slaves, collapsed, causing the financial ruin of thousands of investors and heavy losses for many others, including members of the royal family. King George I called on Robert Walpole, well known for his political and financial acumen, to handle the emergency. With considerable skill and some luck, Walpole acted quickly to restore public credit and confidence, and led the country out of the crisis. A year later, the king appointed him First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader of the House of Commons – making him the most powerful minister in the government. Ruthless, crude, and hard-working, he had a "sagacious business sense" and was a superb manager of men.[35] At the head of affairs for the next two decades, Walpole stabilised the nation's finances, kept it at peace, made it prosperous, and secured the Hanoverian succession.[36][37]

Walpole demonstrated for the first time how a chief minister – a prime minister – could be the actual head of the government under the new constitutional framework. First, recognising that the sovereign could no longer govern directly but was still the nominal head of the government, he insisted that he was nothing more than the "King's Servant".[38] Second, recognising that power had shifted to the Commons, he conducted the nation's business there and made it dominant over the Lords in all matters. Third, recognising that the Cabinet had become the executive and must be united, he dominated the other members and demanded their complete support for his policies. Fourth, recognising that political parties were the source of ministerial strength, he led the Whig party and maintained discipline. In the Commons, he insisted on the support of all Whig members, especially those who held office. Finally, he set an example for future prime ministers by resigning his offices in 1742 after a vote of confidence, which he won by just three votes. The slimness of this majority undermined his power, even though he still retained the confidence of the sovereign.[39][40]

Ambivalence and denial

For all his contributions, Walpole was not a prime minister in the modern sense. The king – not Parliament – chose him; and the king – not Walpole – chose the Cabinet. Walpole set an example, not a precedent, and few followed his example. For over 40 years after Walpole's fall in 1742, there was widespread ambivalence about the position. In some cases, the prime minister was a figurehead with power being wielded by other individuals; in others there was a reversion to the "chief minister" model of earlier times in which the sovereign actually governed.[41] At other times, there appeared to be two prime ministers. During Great Britain's participation in the Seven Years' War, for example, the powers of government were divided equally between the Duke of Newcastle and William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, leading to them both alternatively being described as Prime Minister. Furthermore, many thought that the title "Prime Minister" usurped the sovereign's constitutional position as "head of the government" and that it was an affront to other ministers because they were all appointed by and equally responsible to the sovereign.

For these reasons, there was a reluctance to use the title. Although Walpole is now called the "first" prime minister, the title was not commonly used during his tenure. Walpole himself denied it. In 1741, during the attack that led to Walpole's downfall, Samuel Sandys declared that "According to our Constitution we can have no sole and prime minister". In his defence, Walpole said "I unequivocally deny that I am sole or Prime Minister and that to my influence and direction all the affairs of government must be attributed".[42] George Grenville, Prime Minister in the 1760s, said it was "an odious title" and never used it.[43] Lord North, the reluctant head of the King's Government during the American War of Independence, "would never suffer himself to be called Prime Minister, because it was an office unknown to the Constitution".[44][note 4]

Denials of the premiership's legal existence continued throughout the 19th century. In 1806, for example, one member of the Commons said, "the Constitution abhors the idea of a prime minister". In 1829, Lord Lansdowne said, "nothing could be more mischievous or unconstitutional than to recognise by act of parliament the existence of such an office".[45]

By the turn of the 20th century the premiership had become, by convention, the most important position in the constitutional hierarchy. Yet there were no legal documents describing its powers or acknowledging its existence. The first official recognition given to the office had only been in the Treaty of Berlin in 1878, when Disraeli signed as "First Lord of the Treasury and Prime Minister of her Britannic Majesty".[46][47][48] Not until seven years later, in 1885, did the official records entrench the institution of Prime Minister, using "Prime Minister" in the list of government ministers printed in Hansard.[49][50] Incumbents had no statutory authority in their own right. As late as 1904, Arthur Balfour explained the status of his office in a speech at Haddington: "The Prime Minister has no salary as Prime Minister. He has no statutory duties as Prime Minister, his name occurs in no Acts of Parliament, and though holding the most important place in the constitutional hierarchy, he has no place which is recognised by the laws of his country. This is a strange paradox."[51]

In 1905 the position was given some official recognition when the "prime minister" was named in the order of precedence, outranked, among non-royals, only by the archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland and the Lord Chancellor.[52]

The first Act of Parliament to mention the premiership – albeit in a schedule – was the Chequers Estate Act on 20 December 1917.[53] This law conferred the Chequers Estate owned by Sir Arthur and Lady Lee, as a gift to the Crown for use as a country home for future prime ministers.

Unequivocal legal recognition was given in the Ministers of the Crown Act 1937, which made provision for payment of a salary to the person who is both "the First Lord of the Treasury and Prime Minister". Explicitly recognising two hundred years' of ambivalence, the Act states that it intended "To give statutory recognition to the existence of the position of Prime Minister, and to the historic link between the premiership and the office of First Lord of the Treasury, by providing in respect to that position and office a salary of ..." The Act made a distinction between the "position" (prime minister) and the "office" (First Lord of the Treasury), emphasising the unique political character of the former. Nevertheless, the brass plate on the door of the prime minister's home, 10 Downing Street, still bears the title of "First Lord of the Treasury", as it has since the 18th century as it is officially the home of the First Lord and not the prime minister.[54][55]:P 34

Union of Great Britain and Ireland, 1801

Following the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the British prime minister, William Pitt the Younger, believed the solution to rising Irish nationalism was a union of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland. Britain then included England and Wales and Scotland, but Ireland had its own parliament and government, which were firmly Anglo-Irish and did not represent the aspirations of most Irishmen. For this and other reasons, Pitt advanced his policy, and after some difficulty in persuading the Irish political class to surrender its control of Ireland under the Constitution of 1782, the new union was created by the Acts of Union 1800. With effect from 1 January 1801, Great Britain and Ireland were united into a single kingdom, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Parliament of Ireland came to an end, and until 1922 British ministers were responsible for all three kingdoms of the British Isles.[56]

Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921, which was to be put into effect within one year, the enactment of the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 was concluded on 5 December 1922, creating the Irish Free State. Bonar Law, who had been in office as Prime Minister of Great Britain and Ireland for only six weeks, and who had just won the general election of November 1922, thus became the last prime minister whose responsibilities covered both Britain and the whole of Ireland. Most of a parliamentary session beginning on 20 November was devoted to the Act, and Bonar Law pushed through the creation of the Free State in the face of opposition from the "die hards".[57][58]

Primus inter pares

Emergence of Cabinet government

Despite the reluctance to legally recognise the Premiership, ambivalence toward it waned in the 1780s. During the first 20 years of his reign, George III (1760–1820) tried to be his own "prime minister" by controlling policy from outside the Cabinet, appointing and dismissing ministers, meeting privately with individual ministers, and giving them instructions. These practices caused confusion and dissension in Cabinet meetings; King George's experiment in personal rule was generally a failure. After the failure of Lord North's ministry (1770–1782) in March 1782 due to Britain's defeat in the American Revolutionary War and the ensuing vote of no confidence by Parliament, the Marquess of Rockingham reasserted the prime minister's control over the Cabinet. Rockingham assumed the Premiership "on the distinct understanding that measures were to be changed as well as men; and that the measures for which the new ministry required the royal consent were the measures which they, while in opposition, had advocated." He and his Cabinet were united in their policies and would stand or fall together; they also refused to accept anyone in the Cabinet who did not agree.[note 5] King George threatened to abdicate but in the end reluctantly agreed out of necessity: he had to have a government.

From this time, there was a growing acceptance of the position of Prime Minister and the title was more commonly used, if only unofficially.[31][59] Associated initially with the Whigs, the Tories started to accept it. Lord North, for example, who had said the office was "unknown to the constitution", reversed himself in 1783 when he said, "In this country some one man or some body of men like a Cabinet should govern the whole and direct every measure."[60][61] In 1803, William Pitt the Younger, also a Tory, suggested to a friend that "this person generally called the first minister" was an absolute necessity for a government to function, and expressed his belief that this person should be the minister in charge of the finances.[42]

The Tories' wholesale conversion started when Pitt was confirmed as Prime Minister in the election of 1784. For the next 17 years until 1801 (and again from 1804 to 1806), Pitt, the Tory, was Prime Minister in the same sense that Walpole, the Whig, had been earlier.

Their conversion was reinforced after 1810. In that year, George III, who had suffered periodically from mental instability (possibly due to porphyria), became permanently insane and spent the remaining 10 years of his life unable to discharge his duties. The Prince Regent was prevented from using the full powers of kingship. The regent became George IV in 1820, but during his 10-year reign was indolent and frivolous. Consequently, for 20 years the throne was virtually vacant and Tory Cabinets led by Tory prime ministers filled the void, governing virtually on their own.

The Tories were in power for almost 50 years, except for a Whig ministry from 1806 to 1807. Lord Liverpool was Prime Minister for 15 years; he and Pitt held the position for 34 years. Under their long, consistent leadership, Cabinet government became a convention of the constitution. Although subtle issues remained to be settled, the Cabinet system of government is essentially the same today as it was in 1830.

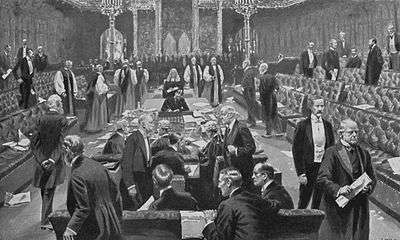

- ^ Gladstone's Cabinet of 1868, Lowes Cato Dickinson, ref. NPG 5116, National Portrait Gallery, London, accessed January 2010

- ^ Shannon, Richard (1984). Gladstone: 1809-1865 (p.342). p. 580. ISBN 0807815918. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

Under this form of government, called the Westminster system, the Sovereign is head of state and titular head of Her Majesty's Government. The Sovereign selects as Prime Minister the person who is able to command a working majority in the House of Commons, and invites him or her to form a government. As the actual Head of Government, the prime minister selects the Cabinet, choosing its members from among those in Parliament who agree or generally agree with his or her intended policies. The prime minister then recommends the Cabinet to the Sovereign who confirms the selection by formally appointing them to their offices. Led by the prime minister, the Cabinet is collectively responsible for whatever the government does. The Sovereign does not confer with members privately about policy, nor attend Cabinet meetings. With respect to actual governance, the monarch has only three constitutional rights: to be kept informed, to advise, and to warn.[62] In practice this means that the Sovereign reviews state papers and meets regularly with the prime minister, usually weekly, when she may advise and warn him or her regarding the proposed decisions and actions of Her Government.[63]

Loyal Opposition

The modern British system includes not only a government formed by the majority party (or coalition of parties) in the House of Commons but also an organised and open opposition formed by those who are not members of the governing party.[46] Called Her Majesty's Most Loyal Opposition, they occupy the benches to the Speaker's left. Seated in the front, directly across from the ministers on the Treasury Bench, the leaders of the opposition form a "shadow government", complete with a salaried "shadow prime minister", the Leader of the Opposition, ready to assume office if the government falls or loses the next election.

Opposing the King's government was considered disloyal, even treasonous, at the end of the 17th century. During the 18th century this idea waned and finally disappeared as the two party system developed. The expression "His Majesty's Opposition" was coined by John Hobhouse, 1st Baron Broughton. In 1826, Broughton, a Whig, announced in the Commons that he opposed the report of a Bill. As a joke, he said, "It was said to be very hard on His Majesty's ministers to raise objections to this proposition. For my part, I think it is much more hard on His Majesty's Opposition to compel them to take this course."[64] The phrase caught on and has been used ever since. Sometimes rendered as the "Loyal Opposition", it acknowledges the legitimate existence of the two party system, and describes an important constitutional concept: opposing the government is not treason; reasonable men can honestly oppose its policies and still be loyal to the Sovereign and the nation.

Informally recognized for over a century as a convention of the constitution, the position of Leader of the Opposition was given statutory recognition in 1937 by the Ministers of the Crown Act.

Great Reform Act and the premiership

British prime ministers have never been elected directly by the public. A prime minister need not be a party leader; David Lloyd George was not a party leader during his service as prime Minister during World War I, and neither was Ramsay MacDonald from 1931 to 1935.[65] Prime ministers have taken office because they were members of either the Commons or Lords, and either inherited a majority in the Commons or won more seats than the opposition in a general election.

Since 1722, most prime ministers have been members of the Commons; since 1902, all have had a seat there.[note 6] Like other members, they are elected initially to represent only a constituency. Former Prime Minister Tony Blair, for example, represented Sedgefield in County Durham from 1983 to 2007. He became Prime Minister because in 1994 he was elected Labour Party leader and then led the party to victory in the 1997 general election, winning 418 seats compared to 165 for the Conservatives and gaining a majority in the House of Commons.

Neither the sovereign nor the House of Lords had any meaningful influence over who was elected to the Commons in 1997 or in deciding whether or not Blair would become Prime Minister. Their detachment from the electoral process and the selection of the prime minister has been a convention of the constitution for almost 200 years.

Prior to the 19th century, however, they had significant influence, using to their advantage the fact that most citizens were disenfranchised and seats in the Commons were allocated disproportionately. Through patronage, corruption and bribery, the Crown and Lords "owned" about 30% of the seats (called "pocket" or "rotten boroughs") giving them a significant influence in the Commons and in the selection of the prime minister.[66][67]

In 1830, Charles Grey, the 2nd Earl Grey and a life-long Whig, became Prime Minister and was determined to reform the electoral system. For two years, he and his Cabinet fought to pass what has come to be known as the Great Reform Bill of 1832.[68][69] The greatness of the Great Reform Bill lay less in substance than in symbolism. As John Bright, a liberal statesman of the next generation, said, "It was not a good Bill, but it was a great Bill when it passed."[70] Substantively, it increased the franchise by 65% to 717,000; with the middle class receiving most of the new votes. The representation of 56 rotten boroughs was eliminated completely, together with half the representation of 30 others; the freed up seats were distributed to boroughs created for previously disenfranchised areas. However, many rotten boroughs remained and it still excluded millions of working-class men and all women.[71][72]

Symbolically, however, the Reform Act exceeded expectations. It is now ranked with Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights as one of the most important documents of the British constitutional tradition.

First, the Act removed the sovereign from the election process and the choice of Prime Minister. Slowly evolving for 100 years, this convention was confirmed two years after the passage of the Act. In 1834, King William IV dismissed Melbourne as premier, but was forced to recall him when Robert Peel, the king's choice, could not form a working majority. Since then, no sovereign has tried to impose a prime minister on Parliament.

Second, the Bill reduced the Lords' power by eliminating many of their pocket boroughs and creating new boroughs in which they had no influence. Weakened, they were unable to prevent the passage of more comprehensive electoral reforms in 1867, 1884, 1918 and 1928 when universal equal suffrage was established.[73]

Ultimately, this erosion of power led to the Parliament Act 1911, which marginalised the Lords' role in the legislative process and gave further weight to the convention that had developed over the previous century[note 7] that a prime minister cannot sit in the House of Lords. The last to do so was Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, from 1895 to 1902.[note 8] Throughout the 19th century, governments led from the Lords had often suffered difficulties governing alongside ministers who sat in the Commons.[74]

Grey set an example and a precedent for his successors. He was primus inter pares (first among equals), as Bagehot said in 1867 of the prime minister's status. Using his Whig victory as a mandate for reform, Grey was unrelenting in the pursuit of this goal, using every parliamentary device to achieve it. Although respectful toward the king, he made it clear that his constitutional duty was to acquiesce to the will of the people and Parliament.

The Loyal Opposition acquiesced too. Some disgruntled Tories claimed they would repeal the bill once they regained a majority. But in 1834, Robert Peel, the new Conservative leader, put an end to this threat when he stated in his Tamworth Manifesto that the bill was "a final and irrevocable settlement of a great constitutional question which no friend to the peace and welfare of this country would attempt to disturb".[75]

Populist prime ministers

The premiership was a reclusive office prior to 1832. The incumbent worked with his Cabinet and other government officials; he occasionally met with the sovereign and attended Parliament when it was in session during the spring and summer. He never went out on the stump to campaign, even during elections; he rarely spoke directly to ordinary voters about policies and issues.

After the passage of the Great Reform Bill, the nature of the position changed: prime ministers had to go out among the people. The Bill increased the electorate to 717,000. Subsequent legislation (and population growth) raised it to 2 million in 1867, 5.5 million in 1884 and 21.4 million in 1918. As the franchise increased, power shifted to the people, and prime ministers assumed more responsibilities with respect to party leadership. It naturally fell on them to motivate and organise their followers, explain party policies, and deliver its "message". Successful leaders had to have a new set of skills: to give a good speech, present a favourable image, and interact with a crowd. They became the "voice", the "face" and the "image" of the party and ministry.

Robert Peel, often called the "model prime minister",[76] was the first to recognise this new role. After the successful Conservative campaign of 1841, J. W. Croker said in a letter to Peel, "The elections are wonderful, and the curiosity is that all turns on the name of Sir Robert Peel. It's the first time that I remember in our history that the people have chosen the first Minister for the Sovereign. Mr. Pitt's case in '84 is the nearest analogy; but then the people only confirmed the Sovereign's choice; here every Conservative candidate professed himself in plain words to be Sir Robert Peel's man, and on that ground was elected."[77]

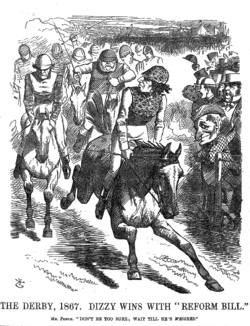

Benjamin Disraeli and William Ewart Gladstone developed this new role further by projecting "images" of themselves to the public. Known by their nicknames "Dizzy" and the "Grand Old Man", their colourful, sometimes bitter, personal and political rivalry over the issues of their time – Imperialism vs. Anti-Imperialism, expansion of the franchise, labour reform, and Irish Home Rule – spanned almost twenty years until Disraeli's death in 1881.[note 9] Documented by the penny press, photographs and political cartoons, their rivalry linked specific personalities with the Premiership in the public mind and further enhanced its status.

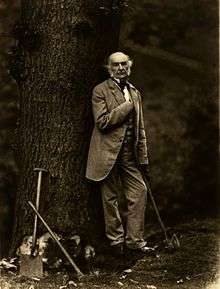

Each created a different public image of himself and his party. Disraeli, who expanded the Empire to protect British interests abroad, cultivated the image of himself (and the Conservative Party) as "Imperialist", making grand gestures such as conferring the title "Empress of India" on Queen Victoria in 1876. Gladstone, who saw little value in the Empire, proposed an anti-Imperialist policy (later called "Little England"), and cultivated the image of himself (and the Liberal Party) as "man of the people" by circulating pictures of himself cutting down great oak trees with an axe as a hobby.

Gladstone went beyond image by appealing directly to the people. In his Midlothian campaign – so called because he stood as a candidate for that county – Gladstone spoke in fields, halls and railway stations to hundreds, sometimes thousands, of students, farmers, labourers and middle class workers. Although not the first leader to speak directly to voters – both he and Disraeli had spoken directly to party loyalists before on special occasions – he was the first to canvass an entire constituency, delivering his message to anyone who would listen, encouraging his supporters and trying to convert his opponents. Publicised nationwide, Gladstone's message became that of the party. Noting its significance, Lord Shaftesbury said, "It is a new thing and a very serious thing to see the Prime Minister on the stump."[78]

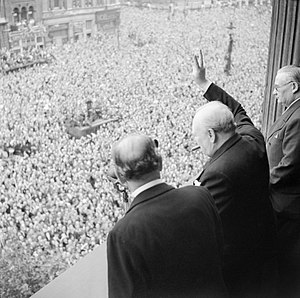

Campaigning directly to the people became commonplace. Several 20th-century prime ministers, such as David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, were famous for their oratorical skills. After the introduction of radio, motion pictures, television, and the internet, many used these technologies to project their public image and address the nation. Stanley Baldwin, a master of the radio broadcast in the 1920s and 1930s, reached a national audience in his talks filled with homely advice and simple expressions of national pride.[79] Churchill also used the radio to great effect, inspiring, reassuring and informing the people with his speeches during the Second World War. Two recent prime ministers, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair (who both spent a decade or more as Prime Minister), achieved celebrity status like rock stars, but have been criticised for their more 'presidential' style of leadership. According to Anthony King, "The props in Blair's theatre of celebrity included ... his guitar, his casual clothes ... footballs bounced skilfully off the top of his head ... carefully choreographed speeches and performances at Labour Party conferences."[80]

Modern premiership

Parliament Act and the premiership

In addition to being the leader of a great political party and the head of Her Majesty's Government, the modern prime minister directs the law-making process, enacting into law his or her party's programme. For example, Tony Blair, whose Labour party was elected in 1997 partly on a promise to enact a British Bill of Rights and to create devolved governments for Scotland and Wales, subsequently stewarded through Parliament the Human Rights Act (1998), the Scotland Act (1998) and the Government of Wales Act (1998).

From its appearance in the fourteenth century Parliament has been a bicameral legislature consisting of the Commons and the Lords. Members of the Commons are elected; those in the Lords are not. Most Lords are called "Temporal" with titles such as Duke, Marquess, Earl, and Viscount. The balance are Lords Spiritual (prelates of the Anglican Church).

For most of the history of the Upper House, Lords Temporal were landowners who held their estates, titles, and seats as a hereditary right passed down from one generation to the next – in some cases for centuries. In 1910, for example, there were nineteen whose title was created before 1500.[81][note 10][82][83]

Until 1911, prime ministers had to guide legislation through the Commons and the Lords and obtain majority approval in both houses for it to become law. This was not always easy, because political differences often separated the chambers. Representing the landed aristocracy, Lords Temporal were generally Tory (later Conservative) who wanted to maintain the status quo and resisted progressive measures such as extending the franchise. The party affiliation of members of the Commons was less predictable. During the 18th century its makeup varied because the Lords had considerable control over elections: sometimes Whigs dominated it, sometimes Tories. After the passage of the Great Reform Bill in 1832, the Commons gradually became more progressive, a tendency that increased with the passage of each subsequent expansion of the franchise.

In 1906, the Liberal party, led by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, won an overwhelming victory on a platform that promised social reforms for the working class. With 379 seats compared to the Conservatives' 132, the Liberals could confidently expect to pass their legislative programme through the Commons.[84][85] At the same time, however, the Conservative Party had a huge majority in the Lords; it could easily veto any legislation passed by the Commons that was against their interests.[86]

For five years, the Commons and the Lords fought over one bill after another. The Liberals pushed through parts of their programme, but the Conservatives vetoed or modified others. When the Lords vetoed the "People's Budget" in 1909, the controversy moved almost inevitably toward a constitutional crisis.[87]

In 1910, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith[note 11] introduced a bill "for regulating the relations between the Houses of Parliament" which would eliminate the Lords' veto power over legislation. Passed by the Commons, the Lords rejected it. In a general election fought on this issue, the Liberals were weakened but still had a comfortable majority. At Asquith's request, King George V then threatened to create a sufficient number of new Liberal Peers to ensure the bill's passage. Rather than accept a permanent Liberal majority, the Conservative Lords yielded, and the bill became law.[88]

The Parliament Act 1911 established the supremacy of the Commons. It provided that the Lords could not delay for more than one month any bill certified by the Speaker of the Commons as a money bill. Furthermore, the Act provided that any bill rejected by the Lords would nevertheless become law if passed by the Commons in three successive sessions provided that two years had elapsed since its original passage. The Lords could still delay or suspend the enactment of legislation but could no longer veto it.[89][90] Subsequently the Lords "suspending" power was reduced to one year by the Parliament Act 1949.

Indirectly, the Act enhanced the already dominant position of Prime Minister in the constitutional hierarchy. Although the Lords are still involved in the legislative process and the prime minister must still guide legislation through both Houses, the Lords no longer have the power to veto or even delay enactment of legislation passed by the Commons. Provided that he or she controls the Cabinet, maintains party discipline, and commands a majority in the Commons, the prime minister is assured of putting through his or her legislative agenda.

Contemporary theories of prime ministerial power

Varying and competing theories of the role and power of the contemporary modern prime minister have emerged in the post-war period, particularly in response to new styles of leadership and governance. The classic view of Cabinet Government was laid out by Walter Bagehot in The English Constitution (1867) in which he described the prime minister as the primus inter pares ("first among equals").[91] This view was challenged in The British Cabinet by John P. Mackintosh, who instead used the terminology of Prime Ministerial Government to describe the British government.[92] This transformation, according to Mackintosh primarily resulted because of the diminishing role of the Cabinet Ministers and because of centralisation of the party machine and the bureaucracy.[92] Richard Crossman also alluded to the presidentialisation of British politics in the Introduction to the 1963 version of Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution.[93] Crossman mentions the Second World War, and its immediate aftermath as a water-shed moment for Britain that led to immense accumulation of power in the hands of the British prime minister[93] These powers, according to Crossman, are so immense that their study require the use of presidential parallels.[93]

Presidentialisation thesis

The most prominent characterisation of prime ministerial power to emerge is the presidentialisation thesis. This asserts that the prime minister has become more detached from Cabinet, party and Parliament and operates as if the occupant of the office is elected directly by the people.[94] The thesis is usually presented with comparisons to the American Presidency. Thomas Poguntke and Paul Webb define it as:

"the development of increasing leadership power resources and autonomy within the party and the political executive respectively, and increasingly leadership-centered electoral processes."[95]

The thesis has been most popularised by Michael Foley, who wrote two books, namely, The Rise of the British Presidency, and The British Presidency: Tony Blair and the Politics of Public Leadership that are solely dedicated to the subject of presidentialisation in Britain.[96][97] Foley writes:

The British Prime Minister has to all intents and purposes turned, not into a British version of an American president, but into an authentically British president.[96]

The thesis has been widely applied to the premiership of Tony Blair as many sources such as former ministers have suggested that decision-making was controlled by him and Gordon Brown, and the Cabinet was no longer used for decision-making.[98] Former ministers such as Clare Short and Chris Smith have criticised the lack of decision-making power in Cabinet. When she resigned, Short denounced "the centralisation of power into the hands of the prime minister and an increasingly small number of advisers".[99] Graham Allen (a Government Whip during Tony Blair's first government) made the case in The Last Prime Minister: Being Honest About the UK Presidency (2003) that in fact the office of Prime Minister has presidential powers.[100]

The notion of presidentialisation in British politics has been criticised, however, due to the structural and constitutional differences between Britain and the United States. These authors cite the stark differences between the British parliamentary model, with its principle of parliamentary sovereignty, and the American presidential model, which has its roots in the principle of separation of powers. For example, according to John Hart, using the American example to explain the accumulation of power in the hands of the British PM is flawed and that changing dynamics of the British executive can only be studied in Britain's own historical and structural sense.[101] The power that a prime minister has over his or her Cabinet colleagues is directly proportional to the amount of support that they have with their political parties and this is often related to whether the party considers them to be an electoral asset or liability. Additionally, when a party is divided into factions a prime minister may be forced to include other powerful party members in the Cabinet for party political cohesion. The prime minister's personal power is also curtailed if their party is in a power-sharing arrangement, or a formal coalition with another party (as happened in the coalition government of 2010 to 2015).[102][103]

Keith Dowding argues, as well, that British prime ministers are already more powerful than the American presidents, as the prime minister is part of the legislature. Therefore, unlike presidents, the prime minister can directly initiate legislation and due to the context British politics functions within, faces fewer "veto players" than a president.[104] Thus, Dowding argues that adding to these powers, makes the prime minister less like presidents, and that what Britain is witnessing can be best explained as Prime Ministerialisation of British politics.[104] The work of Martin J. Smith,[105] importantly, runs contrary to these increasingly personalised conceptualisations of the modern prime minister, however. The Core Executive model asserts that prime ministerial power (especially of individual leaders, such as Thatcher and Blair) has been greatly overstated, and, instead, is both dependent upon and constrained by relationships, or "dependency linkages", with other institutions in government, such as members of the Cabinet or the Treasury. In this model, prime ministers are seen to have improved their institutional position, but rejects the notion that they dominate government and that they act, or have the ability to act, as Presidents due to the aforementioned dependencies and constraints 'that define decision-making in central government.' Smith emphasises "complex resource relationships" (or rather how formal and informal powers are used) and what resources a particular actor possesses. In this case, the prime minister naturally holds more resources than others. These include patronage, control of the Cabinet agenda, appointment of Cabinet Committees and the prime minister's office, as well as collective oversight and the ability to intervene in any policy area. However, all actors possess "resources" and government decision making relies upon resource exchange in order to achieve policy goals, not through command alone.[106] Smith originally used this model to explain the resignation of Margaret Thatcher in 1990, concluding that:

Government is not cabinet government or prime ministerial government. Cabinets and Prime Ministers act within the context of mutual dependence based on the exchange of resources with each other and with other actors and institutions within the core executive.[107]

Prime ministerial leadership as statecraft

Prime ministerial leadership has been described by academics as needing to involve successful statecraft. Statecraft is the idea that successful prime ministers need to maintain power in office in order to achieve any substantive long-term policy reform or political objectives.[108] To achieve successful statecraft leaders must undertake key tasks including demonstrating competence in office, developing winning electoral strategies and carefully managing the constitution in order to protect their political interests. Interviews with former prime ministers and party leaders in the UK found the approach to be an accurate part of some of the core tasks of political leadership.[109] Tony Blair was the first prime minister to be assessed using the academic framework and was judged to be a successful leader in these terms.[110] Assessments have been made of other leaders using the model.[111][112]

Powers and constraints

When commissioned by the sovereign, a potential prime minister's first requisite is to "form a Government" – to create a cabinet of ministers that has the support of the House of Commons, of which they are expected to be a member. The prime minister then formally kisses the hands of the sovereign, whose royal prerogative powers are thereafter exercised solely on the advice of the prime minister and Her Majesty's Government ("HMG"). The prime minister has weekly audiences with the sovereign, whose rights are constitutionally limited: "to warn, to encourage, and to be consulted";[113] the extent of the sovereign's ability to influence the nature of the prime ministerial advice is unknown, but presumably varies depending upon the personal relationship between the sovereign and the prime minister of the day.

The prime minister will appoint all other cabinet members (who then become active Privy Counsellors) and ministers, although consulting senior ministers on their junior ministers, without any Parliamentary or other control or process over these powers. At any time, the PM may obtain the appointment, dismissal or nominal resignation of any other minister; the PM may resign, either purely personally or with the whole government. The prime minister generally co-ordinates the policies and activities of the Cabinet and Government departments, acting as the main public "face" of Her Majesty's Government.

Although the Commander-in-Chief of the British Armed Forces is legally the sovereign, under constitutional practice the prime minister can declare war, and through the Secretary of State for Defence (a position which the prime minister may appoint, dismiss or even appoint themselves to), as chair of the Defence Council, exert power over the deployment and disposition of the UK's forces.

The prime minister makes all the most senior Crown appointments, and most others are made by ministers over whom the prime minister has the power of appointment and dismissal. Privy Counsellors, Ambassadors and High Commissioners, senior civil servants, senior military officers, members of important committees and commissions, and other officials are selected, and in most cases may be removed, by the prime minister. The prime minister also formally advises the sovereign on the appointment of archbishops and bishops of the Church of England,[24] but the prime minister's discretion is limited by the existence of the Crown Nominations Commission. The appointment of senior judges, while constitutionally still on the advice of the prime minister, is now made on the basis of recommendations from independent bodies.

Peerages, knighthoods, and most other honours are bestowed by the sovereign only on the advice of the prime minister. The only important British honours over which the prime minister does not have control are the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Thistle, the Order of Merit, the Order of the Companions of Honour, the Royal Victorian Order, and the Venerable Order of Saint John, which are all within the "personal gift" of the sovereign.

The prime minister appoints officials known as the "Government Whips", who negotiate for the support of MPs and to discipline dissenters. Party discipline is strong since electors generally vote for individuals on the basis of their party affiliation. Members of Parliament may be expelled from their party for failing to support the Government on important issues, and although this will not mean they must resign as MPs, it will usually make re-election difficult. Members of Parliament who hold ministerial office or political privileges can expect removal for failing to support the prime minister. Restraints imposed by the Commons grow weaker when the Government's party enjoys a large majority in that House, or among the electorate. In most circumstances, however, the prime minister can secure the Commons' support for almost any bill by internal party negotiations, with little regard to Opposition MPs.

However, even a government with a healthy majority can on occasion find itself unable to pass legislation. For example, on 9 November 2005, Tony Blair's Government was defeated over plans which would have allowed police to detain terror suspects for up to 90 days without charge, and on 31 January 2006, was defeated over certain aspects of proposals to outlaw religious hatred. On other occasions, the Government alters its proposals to avoid defeat in the Commons, as Tony Blair's Government did in February 2006 over education reforms.[114]

Formerly, a prime minister whose government lost a Commons vote would be regarded as fatally weakened, and the whole government would resign, usually precipitating a general election. In modern practice, when the Government party has an absolute majority in the House, only loss of supply and the express vote "that this House has no confidence in Her Majesty's Government" are treated as having this effect; dissenters on a minor issue within the majority party are unlikely to force an election with the probable loss of their seats and salaries.

Likewise, a prime minister is no longer just "first amongst equals" in HM Government; although theoretically the Cabinet might still outvote the prime minister, in practice the prime minister progressively entrenches his or her position by retaining only personal supporters in the Cabinet. In occasional reshuffles, the prime minister can sideline and simply drop from Cabinet the Members who have fallen out of favour: they remain Privy Counsellors, but the prime minister decides which of them are summoned to meetings. The prime minister is responsible for producing and enforcing the Ministerial Code.

Precedence, privileges and form of address

By tradition, before a new prime minister can occupy 10 Downing Street, they are required to announce to the country and the world that they have "kissed hands" with the reigning monarch, and have thus become Prime Minister. This is usually done by saying words to the effect of:

Her Majesty the Queen [His Majesty the King] has asked me to form a government and I have accepted.[115][116][117][118]

Throughout the United Kingdom, the prime minister outranks all other dignitaries except members of the royal family, the Lord Chancellor, and senior ecclesiastical figures.[note 12]

In 2010, the prime minister received £142,500 including a salary of £65,737 as a member of parliament.[119] Until 2006, the Lord Chancellor was the highest paid member of the government, ahead of the prime minister. This reflected the Lord Chancellor's position at the head of the judicial pay scale. The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 eliminated the Lord Chancellor's judicial functions and also reduced the office's salary to below that of the prime minister.

The prime minister is customarily a member of the Privy Council and thus entitled to the appellation "The Right Honourable". Membership of the Council is retained for life. It is a constitutional convention that only a privy counsellor can be appointed Prime Minister. Most potential candidates have already attained this status. The only case when a non-privy counsellor was the natural appointment was Ramsay MacDonald in 1924. The issue was resolved by appointing him to the Council immediately prior to his appointment as Prime Minister.

According to the now defunct Department for Constitutional Affairs, the prime minister is made a privy counsellor as a result of taking office and should be addressed by the official title prefixed by "The Right Honourable" and not by a personal name. Although this form of address is employed on formal occasions, it is rarely used by the media. As "prime minister" is a position, not a title, the incumbent should be referred to as "the prime minister". The title "Prime Minister" (e.g. "Prime Minister Boris Johnson") is technically incorrect but is sometimes used erroneously outside the United Kingdom and has more recently become acceptable within it. Within the UK, the expression "Prime Minister Johnson" is never used, although it, too, is sometimes used by foreign dignitaries and news sources.

10 Downing Street, in London, has been the official place of residence of the prime minister since 1732; they are entitled to use its staff and facilities, including extensive offices. Chequers, a country house in Buckinghamshire, gifted to the government in 1917, may be used as a country retreat for the prime minister.

Living former prime ministers

There are five living former British prime ministers:

Sir John Major

Sir John Major

(1990–1997) Tony Blair

Tony Blair

(1997–2007) Gordon Brown

Gordon Brown

(2007–2010) David Cameron

David Cameron

(2010–2016)_(cropped).jpg) Theresa, Lady May MP

Theresa, Lady May MP

(2016–2019)

Retirement Honours

Upon retirement, it is customary for the sovereign to grant a prime minister some honour or dignity. The honour bestowed is commonly, but not invariably, membership of the UK's most senior order of chivalry, the Order of the Garter. The practice of creating a retired prime minister a Knight of the Garter (KG) has been fairly prevalent since the mid–nineteenth century. Upon the retirement of a prime minister who is Scottish, it is likely that the primarily Scottish honour of Knight of the Thistle (KT) will be used instead of the Order of the Garter, which is generally regarded as an English honour.[note 13]

Historically it has also been common to grant prime ministers a peerage upon retirement from the Commons, elevating the individual to the Lords. Formerly, the peerage bestowed was usually an earldom.[note 14] The last such creation was for Harold Macmillan, who resigned in 1963. Unusually, he became Earl of Stockton only in 1984, over twenty years after leaving office.

Macmillan's successors, Alec Douglas-Home, Harold Wilson, James Callaghan and Margaret Thatcher, all accepted life peerages (although Douglas-Home had previously disclaimed his hereditary title as Earl of Home). Edward Heath did not accept a peerage of any kind and nor have any of the prime ministers to retire since 1990, although Heath and Major were later appointed as Knights of the Garter.

The most recent former prime minister to die was Margaret Thatcher (1979–1990) on 8 April 2013. Her death meant that for the first time since 1955 (the year in which the Earldom of Attlee was created, subsequent to the death of Earl Baldwin in 1947) the membership of the House of Lords included no former prime minister, a situation which remains the case as of 2020.

See also

- Timeline of prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- List of prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- List of prime ministers of the United Kingdom by length of tenure

- List of prime ministers of the United Kingdom by age

- List of current heads of government in the United Kingdom and dependencies

- List of fictional Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- List of peerages held by Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- List of United Kingdom Parliament constituencies represented by sitting Prime Ministers

- Air transport of the Royal Family and Government of the United Kingdom

- Children of the Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- Historical rankings of Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- Living Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

- Prime Ministerial Car (United Kingdom)

- Prime Minister's Questions

- Records of prime ministers of the United Kingdom

- Spouse of the prime minister of the United Kingdom

Notes

- The Sovereign's prerogative powers are sometimes called reserve powers. They include the sole authority to dismiss a prime minister and government of the day in extremely rare and exceptional circumstances, and other essential powers (such as withholding Royal Assent, and summoning and proroguing Parliament) to preserve the stability of the nation. These reserve powers can be exercised without the consent of Parliament. Reserve powers, in practice, are the court of absolute last resort in resolving situations that fundamentally threaten the security and stability of the nation as a whole and are almost never used.

- Once in office, the prime minister fills not only Cabinet level positions but many other government offices (up to 90 appointments), selected mostly from the House of Commons, distributing them to party members, partly as a reward for their loyalty.[26] The power to make so many appointments to government offices is one of the most effective means the prime minister has of maintaining party discipline in the Commons.

- See e.g. the various orders prescribing fees to be taken in public offices

- The 18th-century ambivalence causes problems for researchers trying to identify who was a prime minister and who was not. Every list of prime ministers may omit certain politicians. For instance, unsuccessful attempts to form ministries – such as the two-day government formed by the Earl of Bath in 1746, often dismissed as the "Silly Little Ministry" – may be included in a list or omitted, depending on the criteria selected.

- This event also marks the beginnings of collective Cabinet responsibility. This principle states that the decisions made by any one Cabinet member become the responsibility of the entire Cabinet.

- Except Lord Home, who resigned his peerage to stand in a by-election soon after becoming prime minister

- As early as 1839, the former Prime Minister Duke of Wellington had argued in the House of Lords that "I have long entertained the view that the Prime Minister of this country, under existing circumstances, ought to have a seat in the other House of Parliament, and that he would have great advantage in carrying on the business of the Sovereign by being there." Quoted in Barnett, p. 246

- The last prime minister to be a member of the Lords during any part of his tenure was Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl of Home in 1963. Lord Home was the last prime minister who was a hereditary peer, but, within days of attaining office, he disclaimed his peerage, abiding by the convention that the prime minister should sit in the House of Commons. A junior member of his Conservative Party who had already been selected as candidate in a by-election in a staunch Conservative seat stood aside, allowing Home to contest and win the by-election, and thus procure a seat in the lower House.

- Even after death their rivalry continued. When Disraeli died in 1881, Gladstone proposed a state funeral, but Disraeli's will specified that he have a private funeral and be buried next to his wife. Gladstone replied, "As [Disraeli] lived, so he died—all display, without reality or genuineness." Disraeli, for his part, once said that GOM (the acronym for "Grand Old Man") really stood for "God's Only Mistake".

- Following a series of reforms in the twentieth century the Lords now consists almost entirely of appointed members who hold their title only for their own lifetime. As of 11 June 2012 the Lords had 763 members (excluding 49 who were on leave of absence or otherwise disqualified from sitting), compared to 646 in the Commons.

- Campbell-Bannerman retired and died in 1908.

- These include: in England and Wales, the Anglican archbishops of Canterbury and York; in Scotland, the Lord High Commissioner and the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland; in Northern Ireland, the Anglican and Roman Catholic archbishops of Armagh and Dublin and the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church.

- This circumstance is somewhat confused, however, as since the Great Reform Act 1832, only seven Scots have served as prime minister. Of these, two – Bonar Law and Ramsay MacDonald – died while still sitting in the Commons, not yet having retired; another, the Earl of Aberdeen, was appointed to both the Order of the Garter and the Order of the Thistle; yet another, Arthur Balfour, was appointed to the Order of the Garter, but represented an English constituency and may not have considered himself entirely Scottish; and of the remaining three, the Earl of Rosebery became a KG, Alec Douglas-Home became a KT, and Gordon Brown remained in the House of Commons as a backbencher until 2015.

- Churchill was offered a dukedom but declined.[120]

References

- "Public List" (PDF). United Nations Protocol and Liaison Office. 24 August 2016. p. 61. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Salaries of Members of Her Majesty's Government from 9th June 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Appendix 4: Ministerial salaries a comparison of entitlements and amounts received (since 2010), £ per annum" (PDF). p. 54. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Pay and expenses for MPs". parliament.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "The principles of government formation (Section 2.8)". The Cabinet Manual (1st ed.). Cabinet Office. October 2011. p. 14. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

Prime Ministers hold office unless and until they resign. If the prime minister resigns on behalf of the Government, the sovereign will invite the person who appears most likely to be able to command the confidence of the House to serve as Prime Minister and to form a government.

- "George I". Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Prime Minister". Gov.UK. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2018.