Essex

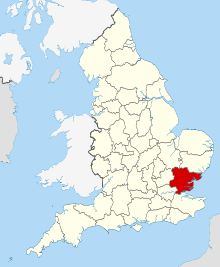

Essex (/ˈɛsɪks/) is a county in the east of England, north-east of London. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south and London to the south-west. The county town is Chelmsford, the only city in the county. For government statistical purposes, Essex is placed in the East of England region, where the inclusion of Essex is one of the main differences between the modern and the historical region.

| Essex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceremonial county | |||||

| |||||

| Motto: "Many Minds, One Heart" | |||||

| |||||

| Coordinates: 51°45′N 0°35′E | |||||

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | ||||

| Constituent country | England | ||||

| Region | East | ||||

| Established | Ancient | ||||

| Ceremonial county | |||||

| Lord Lieutenant | Jennifer Tolhurst[1] | ||||

| High Sheriff | Mrs Julie Fosh[2](2020–21) | ||||

| Area | 3,670 km2 (1,420 sq mi) | ||||

| • Ranked | 11th of 48 | ||||

| Population (mid-2019 est.) | 1,832,752 | ||||

| • Ranked | 7th of 48 | ||||

| Density | 499/km2 (1,290/sq mi) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 90.8% White British 3.6% Other White 2.5% Asian 1.3% Black 1.5% Mixed 0.3% Other | ||||

| Non-metropolitan county | |||||

| County council | Essex County Council | ||||

| Executive | Conservative | ||||

| Admin HQ | Chelmsford | ||||

| Area | 3,465 km2 (1,338 sq mi) | ||||

| • Ranked | 9rd of 26 | ||||

| Population | 1489189 | ||||

| • Ranked | 2th of 26 | ||||

| Density | 431/km2 (1,120/sq mi) | ||||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-ESS | ||||

| ONS code | 22 | ||||

| GSS code | E10000012 | ||||

| NUTS | UKH33 | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Unitary authorities | |||||

| Councils | Southend-on-Sea Borough Council Thurrock Council | ||||

Districts of Essex Unitary County council area | |||||

| Districts | |||||

| Members of Parliament | List of MPs | ||||

| Police | Essex Police | ||||

| Time zone | Greenwich Mean Time (UTC) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time (UTC+1) | ||||

There are four definitions of the extent of Essex, the widest being the Ancient County. Next smallest is the former postal county, followed by the Ceremonial County with the smallest being the administrative county – the area administered by the County Council, which excludes the two unitary authorities of Thurrock and Southend-on-Sea and the areas administered by the Greater London Authority.

The Ceremonial County occupies the eastern part of what was, during the Early Middle Ages, the Kingdom of Essex. As well as rural areas, the county also includes London Stansted Airport, the new towns of Basildon and Harlow, Lakeside Shopping Centre, the port of Tilbury and the borough of Southend-on-Sea.

History

Essex had its roots in the Kingdom of the East Saxons, a polity which is likely to have had its roots in the territory of the Iron Age Trinovantes tribe.[3]

Iron Age

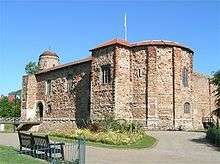

Essex corresponds, fairly closely, to the territory of the Trinovantes tribe. Their production of their own coinage marks them out as one of the more advanced tribes on the island, this advantage (in common with other tribes in the south-east) is probably due to the Belgic element within their elite. Their capital was the oppidum (a type of town) of Colchester, Britain's oldest recorded town, which had its own mint. The tribe were in extended conflict with their western neighbours, the Catuvellauni, and steadily lost ground. By AD 10 they had come under the complete control of the Catuvellauni, who took Colchester as their own capital.[4]

Roman

The Roman invasion of AD 43 began with a landing on the south coast, probably in the Richborough area of Kent. After some initial successes against the Britons, they paused to await reinforcements, and the arrival of the Emperor Claudius. The combined army then proceeded to the capital of the Catevellauni-Trinovantes at Colchester, and took it.

Claudius held a review of his invasion force on Lexden Heath where the army formally proclaimed him Imperator. The invasion force that assembled before him included four legions, mounted auxiliaries and an elephant corps – a force of around 30,000 men.[5] At Colchester, the kings of 11 British tribes surrendered to Claudius.[6]

Colchester became a Roman Colonia, with the official name Colonia Claudia Victricensis ('the City of Claudius' Victory'). It was initially the most important city in Roman Britain and in it they established a temple to the God-Emperor Claudius. This was the largest building of its kind in Roman Britain.[7][8]

The establishment of the Colonia is thought to have involved extensive appropriation of land from local people, this and other grievances led to the Trinovantes joining their northern neighbours, the Iceni, in the Boudiccan revolt.[9] The rebels entered the city, and after a Roman last stand at the temple of Claudius, methodically destroyed it, massacring many thousands. A significant Roman force attempting to relieve Colchester was destroyed in pitched battle, known as the Massacre of the Ninth Legion.

The rebels then proceeded to sack London and St Albans, with Tacitus estimating that 70–80,000 people were killed in the destruction of the three cities. Boudicca was defeated in battle, somewhere in the west midlands, and the Romans are likely to have ravaged the lands of the rebel tribes,[10] so Essex will have suffered greatly.

Despite this, the Trinovantes identity persisted. Roman provinces were divided into civitas for local government purposes – with a civitas for the Trinovantes strongly implied by Ptolemy.[11] The late Roman period, and the period shortly after, was the setting for the King Cole legends based around Colchester.[12]

Anglo-Saxon Period

The name Essex originates in the Anglo-Saxon period of the Early Middle Ages and has its root in the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) name Ēastseaxe ("East Saxons"), the eastern kingdom of the Saxons who had come from the continent and settled in Britain (cf. Middlesex, Sussex and Wessex) during the Heptarchy. Originally recorded in AD 527, Essex occupied territory to the north of the River Thames, incorporating all of what later became Middlesex (which probably included Surrey) and most of what later became Hertfordshire. Its territory was later restricted to lands east of the River Lea.[13]

In AD 824, following the Battle of Ellandun, the kingdoms of the East Saxons, the South Saxons and the Jutes of Kent were absorbed into the kingdom of the West Saxons, uniting Saxland under King Alfred's grandfather Ecgberht. Before the Norman conquest the East Saxons were subsumed into the Kingdom of England.

After the Norman Conquest

After the Norman Conquest, county rather than shire became the more usual term in England's main sub-divisions, but their boundaries and role remained the same.

The invaders established a number of castles in the county, to help protect the new elites in a hostile country. There were castles at Colchester, Castle Hedingham, Rayleigh, Pleshey and elsewhere. Hadleigh Castle was developed much later, in the thirteenth century.

After the arrival of the Normans, the Forest of Essex was established, this was a Royal forest which covered the large majority of the county, however it is important to note that at that time, the term[14] was a legal term, and that at this stage had a weak correlation between woods and commons (sometimes known as 'the vert') and the extent of the forest, most of the Forest of Essex was at that time farmland. The naturalist Oliver Rackham carried out an analysis of Domesday returns for Essex and was able to estimate the county was 20% wooded in 1086[15] with the proportion declining steeply between that point and the depopulation associated with the Black Death. In 1204, the area "north of the Stanestreet" was disafforested. Gradually, the areas subject to forest law diminished, until 'in 1878 what remained of the forest of Essex was disafforested', but at various times they included the forests of Writtle (near Chelmsford), long lost Kingswood (near Colchester),[16] Hatfield, and Waltham Forest (which covered parts of the Hundreds of Waltham, Becontree and Ongar and included the physical forest areas subsequently legally afforested (designated as a legal forest) and known as Epping Forest and Hainault Forest).[17]

Before the county councils

Before the creation of the county councils, county-level administration was limited in nature; lord-lieutenants replaced the sheriffs from the time of Henry VIII and took a primarily military role, responsible for the militia and the Volunteer Force that replaced it.

Most administration was carried out by justices of the peace (JPs) appointed by the Lord-Lieutenant of Essex based upon their reputation. The JPs carried out judicial and administrative duties such as maintenance of roads and bridges, supervision of the poor laws, administration of county prisons and setting the County Rate.[18] JPs carried out these responsibilities, mainly through quarter sessions, and did this on a voluntary basis.

County-wide administration

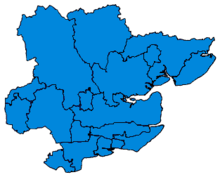

Essex County Council was formed in 1889. However, County Boroughs of West Ham (1889–1965), Southend-on-Sea (1914–1974)[19] and East Ham (1915–1965) formed part of the county but were county boroughs (not under county council control, in a similar manner to unitary authorities today).[20] 12 boroughs and districts provide more localised services such as rubbish and recycling collections, leisure and planning, as shown in the map on the right.

Parish-level administration – changes

A few Essex parishes have been transferred to other counties. Before 1889, small areas were transferred to Hertfordshire near Bishops Stortford and Sawbridgeworth. At the time of the main changes around 1900, parts of Helions Bumpstead, Sturmer, Kedington and Ballingdon-with-Brundon were transferred to Suffolk; and Great Chishill, Little Chishill and Heydon were transferred to Cambridgeshire. Later, part of Hadstock, part of Ashton and part of Chrishall were transferred to Cambridgeshire and part of Great Horkesley went to Suffolk; and several other small parcels of land were transferred to all those counties.

Boundaries

The boundary with Greater London was established in 1965, when East Ham and West Ham county boroughs and the Barking, Chingford, Dagenham, Hornchurch, Ilford, Leyton, Romford, Walthamstow and Wanstead and Woodford districts[20] were transferred to form the London boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Newham, Redbridge and Waltham Forest. Essex became part of the East of England Government Office Region in 1994 and was statistically counted as part of that region from 1999, having previously been part of the South East England region.

Two unitary authorities

In 1998, the boroughs of Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock were separated from the administrative county of Essex after successful requests to become unitary authorities (numbered 13 and 14 on the map to the right).[21][22]

Essex Police covers the administrative county and the two unitary authorities.[23] The county council chamber and main headquarters is at the County Hall in Chelmsford. Before 1938, the council regularly met in London near Moorgate, which with significant parts of the county close to that point and the dominance of railway travel had been more convenient than any place in the county.[24] It currently has 75 elected councillors. Before 1965, the number of councillors reached over 100. The County Hall, made a listed building in 2007, dates largely from the mid-1930s and is decorated with fine artworks of that period, mostly the gift of the family who owned the textile firm Courtaulds.

Physical geography

Borders

The ceremonial county of Essex is bounded to the south by the River Thames and its estuary (a boundary shared with Kent); to the southwest by Greater London; to the west by Hertfordshire with the boundary largely defined by the River Lea and the Stort; to the northwest by Cambridgeshire; to the north by Suffolk, a boundary mainly defined by the River Stour; and to the east by the North Sea.

Coast

The deep estuaries on the east coast give Essex, by some measures, the longest coast of any county.[25] These estuaries mean the county's North Sea coast is characterised by three major peninsulas, each named after the Hundred based on the peninsula:

- Tendring[26] between the Stour and the Colne.

- Dengie[27] between the Blackwater and the Crouch

- Rochford[28] between the Crouch and the Thames

A consequence of these features is that the broad estuaries defining them have been a factor in preventing any transport infrastructure linking them to neighbouring areas on the other side of the river estuaries, to the north and south.

Highest point

The highest point of the county of Essex is Chrishall Common near the village of Langley, close to the Hertfordshire border, which reaches 482 feet (147 m).

Human and economic geography

The county's infrastructure is shaped by its physical geography and proximity to London. Together, these influences both stimulate and constrain the Essex economy.

Economy

A high proportion of the population, especially in the south, work outside the county, commuting to London and elsewhere by rail and by road. These London-based jobs are often well paid and complement the contribution made by the employers based within Essex.

Industry is largely limited to the south of the county, with the majority of the land elsewhere being given over to agriculture. Harlow is a centre for electronics, science and pharmaceutical companies. Chelmsford has been an important location for electronics companies, such as the Marconi Company, since the industry was born; it is also the location for a number of insurance and financial services organisations and, until 2015, was the home of the soft drinks producer Britvic. Basildon is home to New Holland Agriculture's European headquarters and Basildon is home to the Ford Motor Company's British HQ. Debden, near Loughton, is home to a production facility for British and foreign banknotes.

Other businesses in the county are dominated by mechanical engineering, including but not limited to metalworking, glassmaking and plastics and the service sector. Colchester is a garrison town and the local economy is helped by the Army's personnel living there. Basildon is the location of State Street Corporation's United Kingdom HQ International Financial Data Services and remains heavily dependent on London for employment, due to its proximity and direct transport routes. Southend-on-Sea is home to the Adventure Island theme park and is one of the few still growing British seaside resorts, benefiting from modern and direct rail links from Fenchurch Street railway station and Liverpool Street station (so that housing is in high demand, especially for financial services commuters), which maintains the town's commercial and general economy.

Parts of eastern Essex suffer from high levels of deprivation; one of the most highly deprived wards is in the seaside town of Clacton.[29] In the Indices of deprivation 2007, Jaywick was identified as the most deprived Lower Super Output Area in Southern England.[30] Unemployment was estimated at 44% and many homes were found to lack very basic amenities. The Brooklands and Grasslands area of Jaywick was found to be the third-most deprived area in England; two areas in Liverpool and Manchester were rated more deprived. In contrast, west and south-west Essex is one of the most affluent parts of eastern England, forming part of the London commuter belt. There is a large middle class here and the area is widely known for its private schools. In 2008, The Daily Telegraph found Ingatestone and Brentwood to be the 14th- and 19th-richest towns in the UK respectively.[31]

Settlement patterns

The pattern of settlement in the county is diverse. The areas closest to London are the most densely settled, though the Metropolitan Green Belt has prevented the further sprawl of London into the county. The Green Belt was initially a narrow band of land, but subsequent expansions meant it was able to limit the further expansion of many of the commuter towns close to the capital. The Green Belt zone close to London includes many prosperous commuter towns, as well as the new towns of Basildon and Harlow, originally developed to resettle Londoners after the destruction of London housing in the Second World War; they have since been significantly developed and expanded. Epping Forest also prevents the further spread of the Greater London Urban Area. As it is not far from London, with its economic magnetism, many of Essex's settlements, particularly those near or within short driving distance of railway stations, function as dormitory towns or villages where London workers raise their families. In these areas a high proportion of the population commute to London, and the wages earned in the capital are typically significantly higher than more local jobs. Many parts of Essex therefore, especially those closest to London, have a major economic dependence on London and the transport links that take people to work there.

Jun2005.jpg)

Part of the south-east of the county, already containing the major population centres of Basildon, Southend and Thurrock, is within the Thames Gateway and designated for further development. Parts of the south-west of the county, such as Buckhurst Hill and Chigwell, are contiguous with Greater London neighbourhoods and therefore form part of the Greater London Urban Area.

A small part of the south-west of the county, Sewardstone, is the only settlement outside Greater London to be covered by a postcode district of the London post town (E4). With the exception of major towns, such as Colchester, Chelmsford and Southend-on-Sea, the county is rural, with many small towns, villages and hamlets largely built in the traditional materials of timber and brick, with clay tile or thatched roofs.

Transport

Much of Essex lies within the London commuter belt, with radial transport links to the capital an important part of the area's economy. There are nationally or regionally important ports and airports and these also rely on the Essex infrastructure, causing an additional load on the local road and rail links.

Railway

Essex's railway routes to London are, running clockwise:

- The West Anglia Main Line from Liverpool Street to Harlow, Stansted Airport and onward to Cambridgeshire.

- The southern part of Epping Forest district is served by the London Underground Central line.

- The Great Eastern Main Line from Liverpool Street to Shenfield, Chelmsford, Colchester and onto East Anglia. The Great Eastern includes branch lines to:

- Harwich and its port. The nearby port of Felixstowe in Suffolk is served by a separate branch.

- The Sunshine Coast Line linking Colchester to the seaside resorts of Clacton-on-Sea and Walton-on-the-Naze via the picturesque towns of Wivenhoe and Great Bentley.

- Braintree.

- Branch from Marks Tey to Sudbury (Suffolk) and villages in-between.

- In the densely populated south, there is a branch to Southend Victoria, the Rochford Peninsula and several south Essex towns. This branch has a sub-branch – the Crouch Valley Line – linking Wickford to the remote Dengie Peninsula, including Burnham-on-Crouch and Southminster.[32]

- Like the Southend Victoria branch, the London, Tilbury & Southend Railway also serves Southend (Southend Central), the Rochford Peninsula and many towns in the densely populated south of the county. The London terminus is Fenchurch Street and heading eastward from Barking, the line separates into three, which later merge back into one by the time the railway reaches Pitsea.

The Essex Thameside franchise is operated by c2c. The Greater Anglia routes (both the West Anglia and Great Eastern Main Line and their branches) are operated by Greater Anglia.

South Essex Rapid Transit is a proposed public transport scheme which would provide a fast, reliable public transport service in and between Thurrock, Basildon and Southend.[33]

Road

Essex has six main strategic routes, five of which reflect the powerful influence exerted by London.

The M25 is London's orbital motorway which redistributes traffic across the London area. It includes the Dartford Road Crossings, over the Thames Estuary, linking Essex to Kent.

There are four radial commuter routes into the capital:

- M11 motorway, which also serves Stansted Airport and provides commuter links to Cambridge.

- A12, to East Anglia via Chelmsford and Colchester. It also serves the ports of Harwich and Felixstowe (Suffolk).

- A127, to the Rochford Peninsula, including Southend and Southend Airport. This is no longer maintained as a trunk road.

- A13, to the Rochford Peninsula, also including Southend. It also serves the expanding Tilbury and London Gateway ports.

The A120 is a major route heading west from the ports of Harwich and Felixstowe (Suffolk) and, like the A12, the route was in use during the Roman period and, in part at least, before then.

Ports and waterborne transport

The Port of Tilbury is one of Britain's three major ports and has proposed a major extension onto the site of the former Tilbury power stations.[34] The port of Harwich has passenger and freight services to the Hook of Holland and a freight service to Europoort. A service to Esbjerg, Denmark ceased in September 2014[35] and earlier a service to Cuxhaven in Germany was discontinued in December 2005.

The UK's largest container terminal London Gateway at Shell Haven in Thurrock partly opened in November 2013; final completion date is yet to be confirmed.[36] The port was opposed by the local authority and environmental and wildlife organisations.[37][38][39]

The ports have branch lines to connect them to the national rail network. These freight movements conflict with the needs of commuter passenger services, limiting their frequency and reliability.[40]

East of the Dartford Road Crossing to Dartford in Kent, across the Thames Estuary, a pedestrian ferry to Gravesend, Kent operates from Tilbury during limited daily hours; there are pedestrian ferries across some of Essex's rivers and estuaries in spring and summer.

Airports

The main airport in Essex is Stansted Airport, serving destinations in Europe, North Africa and Asia.[41] The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, formed in May 2010, agreed not to allow a further runway until a set time period, so curtailing the operator's ambitions for expansion. London Southend Airport, once one of Britain's busiest airports, opened a new runway extension, terminal building and railway station in March 2012.[42] It has a station on the Shenfield to Southend Line, with a direct link to London.

Southend Airport has scheduled flights to Ireland, the Channel Islands and multiple destinations in Europe. Essex has several smaller airfields, some of which owe their origins to military bases built during World War I or World War II, giving pleasure flights or flying lessons; these include Clacton Airfield, Earls Colne Airfield and Stapleford Aerodrome.

Politics

Westminster and the 2016 EU referendum

Essex is a strongly Conservative county. As of the 2019 general election, all 18 Essex seats are represented by Conservatives, all of which recorded absolute majorities (over 50% of the vote). There have previously been some Labour MPs: most recently, Thurrock, Harlow and Basildon in Labour's 2005 election victory. The Liberal Democrats until 2015 had a sizeable following in Essex, gaining Colchester in the 1997 general election.

The 2015 general election saw a large vote in Essex for the UK Independence Party (UKIP), with its only MP, Douglas Carswell, retaining the seat of Clacton that he had won in a 2014 by-election, and other strong performances, notably in Thurrock and Castle Point. But in the 2017 general election, UKIP's vote share plummeted by 15.6% while both Conservative and Labour vote shares rose by 9%. This resulted in Labour regaining second place in Essex, increasing their vote share across the county and cutting some Conservative majorities in areas which had been unaffected by the 1997 general election, namely Rochford and Southend East and Southend West.

In 2015, Thurrock epitomised a three-party race with UKIP, Labour and the Conservatives gaining 30%, 31% and 32% respectively. In 2017, the Conservatives held Thurrock with an increased share of the vote, but a smaller margin of victory. It was the constituency in which UKIP performed best in 2017, with 20% of the vote while all other areas had been reduced to low single figure vote shares. Several new MPs were elected in the 2017 election, with Alex Burghart, Vicky Ford, Giles Watling and Kemi Badenoch all replacing senior Conservative politicians such as Sir Eric Pickles, Sir Simon Burns, Douglas Carswell and Sir Alan Haselhurst, respectively.

At the 2019 general election, Castle Point constituency recorded the highest vote share for the Conservatives in the entire United Kingdom, with 76.7%. The most marginal constituency in the county is Colchester, however the Conservative Party still command a majority of over 9,400 votes.

In the EU referendum, Essex voted overwhelmingly to leave the EU, with all 14 District Council areas voting to leave, the smallest margin being in Uttlesford.[43]

2019 UK general election in Essex

| Party | Votes cast | % | Seats | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ± | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ± | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ± | ||

| Conservative | 436,758 | 528,949 | 577,118 | 49.6 | 59.0 | 64.8 | 17 | 18 | 18 | ||||

| Labour | 171,026 | 261,671 | 189,471 | 19.4 | 29.2 | 21.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Liberal Democrat | 58,592 | 46,254 | 95,078 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 10.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Green | 25,993 | 12,343 | 20,438 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Independents | 6,919 | 4,179 | 10,224 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Monster Raving Loony | N/A | N/A | 804 | N/A | N/A | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| English Democrats | 453 | 289 | 532 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| SDP | N/A | N/A | 394 | N/A | N/A | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Psychedelic Future | N/A | N/A | 367 | N/A | N/A | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| YPP | 80 | 110 | 170 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| UKIP | 177,756 | 41,478 | N/A | 20.2 | 4.6 | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Total | 879,918 | 896,231 | 894,608 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 18 | 18 | 18 | ||||

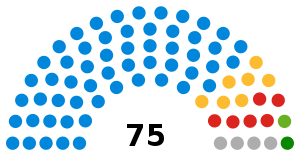

Essex County Council

This is the county council that governs the non-metropolitan county of Essex in England. It has 75 councillors, elected from 70 divisions, some of which elect more than one member, and is currently controlled by the Conservative Party.[2] The council meets at County Hall in the centre of Chelmsford.

At the time of the 2011 census it served a population of 1,393,600, which makes it one of the largest local authorities in England. As a non-metropolitan county council, responsibilities are shared between districts (including boroughs) and in many areas also between civil parish (including town) councils. Births, marriages/civil partnerships and death registration, roads, libraries and archives, refuse disposal, most of state education, of social services and of transport are provided at the county level.[3]

The county council was formed in 1889, governing the administrative county of Essex. The county council was reconstituted in 1974 as a non-metropolitan county council, regaining jurisdiction in Southend-on-Sea; however, the non-metropolitan county was reduced in size in 1998 and the council passed responsibilities to Southend-on-Sea Borough Council and Thurrock Council in those districts. For certain services the three authorities co-operate through joint arrangements, such as the Essex fire authority.

At the 2013 County Council elections the Conservative Party retained overall control of the council, but its majority fell from twenty-two to four councillors. UKIP, Labour and the Liberal Democrats each won nine seats. Out of those three parties, UKIP gained the largest share of the county-wide vote, more than 10% ahead of Labour.[3] The Liberal Democrats remain as the official Opposition, despite winning fewer votes.[3] The Green Party gained two seats on the council, despite its overall share of the vote falling. The Independent Loughton Residents Association and the Canvey Island Independent Party both returned one member and an Independent candidate was also elected.

The 2017 County Council elections saw a county-wide wipeout of UKIP. The Conservative Party profited most from this loss, regaining many of the seats it had lost at the previous election. Labour, despite a slight rise in its share of the vote, had fewer councillors elected. The Liberal Democrats also saw a notable revival, but were unable to translate this into seats. The Conservatives retained firm control of the council. The next election will be in 2021.

The county of Essex is divided into 12 district and borough councils with 2 unitary authorities (Southend on Sea and Thurrock). The 12 councils manage housing, local planning, refuse collection, street cleaning, elections and meet in their respective civic offices. The local representatives are elected in parts in local elections, held every year.[44]

With regard to the two unitary authorities, the county council is not used to conduct business, but works closely with the unitary authorities to deliver the "best value service" to all residents.

2017 Essex County Council election

| Party | Votes cast | % | Seats | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2013 | 2017 | ± | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 | ± | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 | ± | ||

| Conservative | 169,975 | 112,229 | 184,901 | 43.3 | 34.4 | 49.3 | 60 | 42 | 56 | ||||

| Labour | 42,334 | 57,290 | 63,470 | 10.8 | 16.4 | 16.9 | 1 | 9 | 6 | ||||

| Liberal Democrat | 79,085 | 35,651 | 51,524 | 20.1 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 12 | 9 | 7 | ||||

| UKIP | 18,186 | 90,812 | 29,796 | 4.6 | 27.6 | 7.9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | ||||

| Green | 26,547 | 15,187 | 15,187 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Independents | 5,845 | 4,631 | 12,506 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Residents for Uttlesford | N/A | N/A | 5,231 | N/A | N/A | 1.4 | 0 | 0*(1) | 0 | ||||

| Canvey Island Independents | 1,655 | 2,777 | 3,654 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Loughton Residents | 2,764 | 3,286 | 2,824 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Tendring First | 5,866 | 4,093 | 1,332 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| BNP | 35,037 | 909 | 847 | 8.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| English Democrats | 5,212 | 835 | 58 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| TUSC | N/A | 431 | N/A | N/A | 0.1 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| National Front | N/A | 304 | N/A | N/A | 0.1 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Total | 392,506 | 328,435 | 372,834 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 75 | 75 | 75 | ||||

Youth councils

The Essex County Council also has a Youth Assembly, 75 members aged between 11 and 19 who aim to represent all young people in their districts across Essex. They decide on the priorities for young people and campaign to make a difference.[45] With this, some district and unitary authorities may have their own youth councils, such as Epping Forest,[46] Uttlesford[47] and Harlow.[48]

All these councillors are elected by their schools. The elections to the Young Essex Assembly occur in the respective schools in which the candidates are standing, likewise for the youth councils at a district and unitary level. These young people will then go on to represent their school and their parish/ward or (in the case of the Young Essex Assembly) their entire district.

The initiative seeks to engage younger people in the county and rely on the youth councillors of all status to work closely with schools and youth centres to improve youth services in Essex and help promote the opinions of the Essex youth generation.

Local government

Town and parish councils vary in size from those with a population of around 200 to those with a population of over 30,000. Annual expenditure can vary greatly, depending on the circumstances of the individual council. Parish and town councils (local councils) have the same powers and duties, but a town council may elect a town mayor, rather than a chairman, each year in May.

There are just under 300 town and parish councils within Essex.[44]

Local councils play a vital role in representing the interests of their communities and improving the quality of life and the local environment. They can also influence other decision makers and can deliver services to meet local needs. Their powers and duties range from maintaining allotments and open spaces, to crime prevention and providing recreation facilities.

Local councils have the right to become statutory consultees at both district and county level and, although the decision remains with the planning authorities, local councils can influence the decision-making process by making informed comments and recommendations.[44]

Education

Education in Essex is substantially provided by three authorities: Essex County Council and the two unitary authorities, Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock. In all there are some 90 state secondary schools provided by these authorities, the majority of which are comprehensive, although one in Uttlesford, two in Chelmsford, two in Colchester and four in Southend-on-Sea are selective grammar schools. There are also various independent schools particularly, as mentioned above, in rural parts and the west of the county.[49][50]

The University of Essex, which was established in 1963, is located just outside Colchester, with two further campuses in Loughton and Southend-on-Sea. University Campus Suffolk, with a main campus in Ipswich and five centres in the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk, is a joint venture between University of Essex and East Anglia polytechnic.

Anglia Ruskin University has a campus in Chelmsford. Lord Ashcroft International Business School, Faculty of Medical Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Anglia Law School, Faculty of Health, Social Care & Education and School of Medicine are located in the campus area.

Finally, Writtle University College, based on the outskirts of Chelmsford in the village of Writtle, is the only land-based Higher Education Institution in Essex. It offers both higher and further education in land-based subjects.

Culture

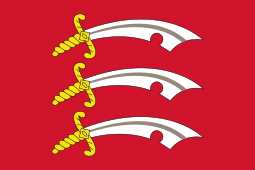

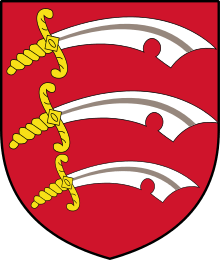

The county's coat of arms comprises three Saxon seax knives (although they look rather more like scimitars), mainly white and pointing to the right (from the point of view of the observer), arranged vertically one above another on a red background (Gules three Seaxes fesswise in pale Argent pommels and hilts Or, points to the sinister and notches to the base); the three-seax device is also used as the official logo of Essex County Council; this was granted in 1932.[51] The emblem was attributed to Anglo-Saxon Essex in Early Modern historiography. The earliest reference to the arms of the East Saxon kings was by Richard Verstegan, the author of A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence (Antwerp, 1605), claiming that "Erkenwyne king of the East-Saxons did beare for his armes, three [seaxes] argent, in a field gules". There is no earlier evidence substantiating Verstegan's claim, which is an anachronism for the Anglo-Saxon period seeing that heraldry only evolved in the 12th century, well after the Norman Conquest.

John Speed in his Historie of Great Britaine (1611) follows Verstegan in his descriptions of the arms of Erkenwyne, but he qualifies the statement by adding "as some or our heralds have emblazed".[51]

Essex is also home to the Dunmow Flitch Trials, a traditional ceremony that takes place every four years and consists of a test of a married couple's devotion to one another. A common claim of the origin of the Dunmow Flitch dates back to 1104 and the Augustinian priory of Little Dunmow, founded by Lady Juga Baynard. Lord of the Manor Reginald Fitzwalter and his wife dressed themselves as humble folk and begged blessing of the Prior a year and a day after marriage. The prior, impressed by their devotion, bestowed upon them a flitch of bacon. Upon revealing his true identity, Fitzwalter gave his land to the priory on condition that a flitch should be awarded to any couple who could claim they were similarly devoted.

By the 14th century, the Dunmow Flitch Trials appear to have achieved a significant reputation outside the local area. The author William Langland, who lived on the Welsh borders, mentions it in his 1362 book The Vision of Piers Plowman in a manner that implies general knowledge of the custom among his readers.[52]

The Essex dialect, an accent related to the Suffolk dialect, was formerly prevalent in the county but has now been mostly replaced by Estuary English.

Sport

Football

Essex is home to two English Football League teams: Southend United and Colchester United. Both teams have reached as high as the Championship (the second tier of English football) at some point in their history. As of 2020–21, both teams are in League Two.

Billericay Town, Braintree Town, Chelmsford City and Concord Rangers all play in the National League South. The highest domestic trophy for non-league teams, the FA Trophy, has been won on three occasions by Essex teams: Colchester United (1992), Canvey Island (2001) and by Grays Athletic in 2006. The FA Vase has been won three times by Billericay Town in 1976, 1977 and 1979, and by Stansted in 1984.

While the area was later annexed into Greater London, West Ham United was founded in what was then Essex and is the most successful club founded in the county.

Cricket

Essex County Cricket Club became a First-Class County in 1894. The county has won 8 County Championship league titles; 6 of these were won during the dominant period between 1979 and 1992, with a gap of 25 years before the county's next title in 2017.

Other sports

The county is also home to the Chelmsford Chieftains ice hockey team and the Essex Leopards basketball team. It is home to the amateur rugby league football teams the Eastern Rhinos and Brentwood Eels (Essex Eels). Defunct teams include the Essex Pirates basketball team, as well as speedway teams the Lakeside Hammers (formerly Arena Essex Hammers), the Rayleigh Rockets and the Romford Bombers.

During the 2012 London Olympics, Hadleigh Farm played host to the mountain bike races. London Stadium, which was the host of the games, is located within the historical Essex boundaries.

Essex has one horse racing venue, Chelmsford City Racecourse at Great Leighs. Horse racing also took place at Chelmsford Racecourse in Galleywood until 1935. The county has one current greyhound racing track, Harlow Stadium. Rayleigh Weir Stadium and Southend Stadium are former greyhound venues.

Team Essex Volleyball Club is Chelmsford's national league volleyball club. It has four teams which play in Volleyball England's national volleyball league. Its men's 1st team currently competes in the top division in the country, the Super 8s, while the women's 1st team competes one tier below the men. The club has a strong junior programme and trains at The Boswells School in Chelmsford.

Sportspeople

Many famous sports stars have come from or trained in Essex. These have included swimmer Mark Foster; cricket stars Trevor Bailey, Nasser Hussain, Alastair Cook and Graham Gooch; footballers Peter Taylor, James Tomkins, Justin Edinburgh, Nigel Spink; tennis stars John Lloyd and David Lloyd; Olympic Gold-winning gymnast Max Whitlock; Olympic sailing champion Saskia Clark; World Champion snooker stars Stuart Bingham and Steve Davis; world champion boxers Terry Marsh, Nigel Benn and Frank Bruno; London Marathon winner Eamonn Martin; international rugby players Malcolm O'Kelly and Stuart Barnes; Formula 1 sports car drivers Johnny Herbert and Perry McCarthy.

Landmarks

Over 14,000 buildings have listed status in the county and around 1,000 of those are recognised as of Grade I or II* importance.[53] The buildings range from the 7th century Saxon church of St Peter-on-the-Wall, to the Royal Corinthian Yacht Club which was the United Kingdom's entry in the 'International Exhibition of Modern Architecture' held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1932. Southend Pier is in the Guinness Book of Records as the longest pleasure pier in the world.

The church of St Peter-on-the-Wall, Bradwell-on-Sea

The church of St Peter-on-the-Wall, Bradwell-on-Sea The Grade I listed Hedingham Castle, with the best preserved Norman keep in the UK

The Grade I listed Hedingham Castle, with the best preserved Norman keep in the UK- Thaxted Guildhall, dating from around 1450

- The 17th century Audley End House, Saffron Walden

Places of interest

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Mosques | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

- Abberton Reservoir

- Anglia Ruskin University Chelmsford campus

- Ashdon (The site of the ancient Bartlow Hills and also a claimant as the location of the Battle of Ashingdon)

- Ashingdon (The site of the Battle of Ashingdon in 1016), near Southend, with its isolated St Andrews Church and site of England's earliest aerodrome at South Fambridge

- Audley End House and Gardens, Saffron Walden

- Brentwood Cathedral

- Clacton-on-Sea

- Chelmsford Cathedral

- Colchester Castle

.svg.png)

- Colchester Zoo

- Colne Valley Railway

- Cressing Temple

- East Anglian Railway Museum

.svg.png)

- Epping Forest

- Epping Ongar Railway

- Finchingfield (home of the author Dodie Smith)

- Frinton-on-Sea

- Great Bentley, which has the largest village green in England

- Hadleigh Castle

- Harlow New Town

- Hedingham Castle, between Stansted and Colchester, to the north of Braintree

- Ingatestone Hall, Ingatestone, between Brentwood and Chelmsford

- Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker

- Lakeside Shopping Centre

- Loughton, near Epping Forest

- Maldon historic market town, close to Chelmsford and the North Sea, and site of the Battle of Maldon

- Mangapps Railway Museum

.svg.png)

- Marsh Farm Country Park (South Woodham Ferrers)

- Mersea Island, birdwatching and rambling resort with one settlement, West Mersea

- Mistley Towers, Manningtree, between Colchester and Ipswich, near Alton Water.

- Mountfitchet Castle

- North Weald Airfield

- Northey Island

- Orsett Hall Hotel, Prince Charles Avenue, Orsett near Chadwell St Mary

- St Peter-on-the-Wall

- Saffron Walden

.svg.png)

- Southend Pier

- Thames Estuary

- Tilbury Fort

- Thaxted, south of Saffron Walden

- Thurrock Thameside Nature Park

- University of Essex (Wivenhoe Park, Colchester and Loughton)

- Waltham Abbey

Notable people

Sister counties and regions

See also

- Custos Rotulorum of Essex – Keepers of the Rolls

- Earl of Essex

- Essex (UK Parliament constituency)

- Essex Police and Crime Commissioner

- Healthcare in Essex

- High Sheriff of Essex

- List of civil parishes in England

- List of Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Essex

- Lord Lieutenant of Essex

- Q Camp: WWII camp in Essex

Notes and references

- "Lord-Lieutenant of Essex: Jennifer Tolhurst". GOV.UK. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "No. 62943". The London Gazette. 13 March 2020. p. 5161.

- Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p46. Barbara Yorke. Yorke makes reference to research by Rodwell and Rodwell (1986) and Bassett (1989)

- Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. passim. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- Described in 'The Essex Landscape', by John Hunter, Essex Record Office, 1999. Chapter 4

- Life in Roman Britain, Anthony Birley, 1964

- Crummy, Philip (1997) City of Victory; the story of Colchester – Britain's first Roman town. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 897719 04 3)

- Wilson, Roger J.A. (2002) A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain (Fourth Edition). Published by Constable. (ISBN 1-84119-318-6)

- Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 48. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 51. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- Rippon, Stephen (2018) [2018]. Kingdom, Civitas, and County. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-875937-9.

- Gray, Adrian (1987) [1987]. Tales of Old Essex. Berkshire: Countryside Books. p. 27. ISBN 0-905392-98-1.

- Vision of Britain Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Essex ancient county boundaries map

- forest

- Rackham, Oliver (1990) [1976]. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. New York: Phoenix Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-8421-2469-7.

- Rackham, Oliver (1990) [1976]. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. New York: Phoenix Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-8421-2469-7.

- Raymond Grant (1991). The royal forests of England. Wolfeboro Falls, NH: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-781-X. OL 1878197M. 086299781X. see table, p224 for Essex Stanestreet and p221-229 for details of each forest

- English Social History, Trevelyan

- Vision of Britain Archived 14 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine – Southend-on-Sea MB/CB

- Vision of Britain Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Essex admin county (historic map Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine)

- Essex County Council Archived 24 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine – District or Borough Councils

- OPSI Archived 4 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine – The Essex (Boroughs of Colchester, Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock and District of Tendring) (Structural, Boundary and Electoral Changes) Order 1996

- OPSI Archived 12 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine – The Essex (Police Area and Authority) Order 1997

- "Conference on Labour History in Essex – Spring 2005" (PDF). Labour Heritage. p. 2. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Ordnance Survey Blog on the Essex coastline and the difficulty of measuring coastlines https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/blog/2017/01/english-county-longest-coastline/

- A link to show the term tendring Pen. in use and to describe the name as resulting from the name of the Hundred

- link to show the Dengie Pen. in use and linking that to Hundred organisation

- A link to show the term Rochford Pen. in use http://www.visitessex.com/rochford.aspx

- "Did you know deprivation in Chelmsford Diocese". Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "Jackwich: Village 'third most deprived area in UK'". Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "Britain's richest towns: 20 – 11". The Daily Telegraph. London. 18 April 2008. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014.

- "National Rail Enquiries – Official source for UK train times and timetables". www.nationalrail.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- "FAQs". www.sert.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Link to website promoting the Tilbury2 proposals http://www.tilbury2.co.uk/

- "DFDS Harwich to Esbjerg ferry route's final journey – BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- "London Gateway : Home". www.londongateway.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- Portswatch: Current Port Proposals: London Gateway (Shell Haven) Archived 25 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- Thurrock Council. (26 February 2003). Shell Haven public inquiry opens Archived 15 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- Dredging News Online. (18 May 2008). Harbour Development, Shell Haven, UK Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- Anglia Route Study, describes opportunities and constraints for the E of England rail network – https://www.networkrail.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Anglia-Route-Study-UPDATED-1.pdf

- Cheap flights from London Stansted to Sharm El Sheikh Archived 27 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine. easyJet.com (17 February 2013). Retrieved on 17 July 2013.

- Topham, Gwyn (5 March 2012). "London Southend airport: flying under the radar (and to the left of the pier)". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- "Two of UK's top Leave districts in Essex". BBC News. 24 June 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Local government structure". www.essex.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "About us". www.young-essex-assembly.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Warr, Mike. "Youth Council". www.eppingforestdc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- R4U (14 December 2016). "Residents for Uttlesford [R4U] | R4U's Uttlesford Youth Council initiative gets green light". Residents for Uttlesford. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- "Youth Council | Harlow Council". www.harlow.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Essex County Council. (2006). Secondary School Information Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- independent schools Directory. (2009). Independent Schools in Essex Archived 30 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- Robert Young. (2009). Civic Heraldry of England and Wales. Essex Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Dunmow Flitch Trials – History – Background". www.dunmowflitchtrials.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- Bettley, James. (2008). Essex Explored: Essex Architecture. Essex County Council. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- "Colchester Castle Museum-Index". Colchestermuseums.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Essex. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Essex (England). |

- Essex at Curlie

- Essex County Council

- Seax – Essex Archives Online

- Images of Essex at the English Heritage Archive