London Borough of Tower Hamlets

The London Borough of Tower Hamlets is a London borough located in East London; it covers much of the traditional East End. It was formed in 1965 from the merger of the former metropolitan boroughs of Stepney, Poplar and Bethnal Green. The new authority's unusual name was taken from an alternative title for the Tower Division; the area of south-east Middlesex, focused on (but not limited to) the area of the modern borough, which owed military service to the Tower of London.

Tower Hamlets | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms  Council logo | |

| Motto(s): From Great Things to Greater | |

Tower Hamlets shown within Greater London | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | London |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Created | 1 April 1965 |

| Admin HQ | Clove Crescent, Blackwall |

| Government | |

| • Type | London borough council |

| • Body | Tower Hamlets London Borough Council |

| • Leadership | Mayor & Cabinet (Labour) |

| • Executive mayor | John Biggs (Labour) |

| • London Assembly | Unmesh Desai (Labour) AM for City and East |

| • MPs | Rushanara Ali (Labour) Apsana Begum (Labour) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.63 sq mi (19.77 km2) |

| Area rank | 311th (of 317) |

| Population (mid-2019 est.) | |

| • Total | 324,745 |

| • Rank | 33rd (of 317) |

| • Density | 43,000/sq mi (16,000/km2) |

| • Ethnicity[1] | 32% Bangladeshi 31.2% White British 12.4% Other White 3.7% Black African 3.2% Chinese 2.1% Black Caribbean 1.1% Black Caribbean & White 0.6% Black African & White 1.2% Asian & White 1.2% Other Mixed 2.7% Indian 1% Pakistani 2.3% Other Asian 1.5% Other Black 1% Arab 1.5% White Irish 0.1% White Gypsy or Irish Traveller 1.3% Other |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcodes | |

| ONS code | 00BG |

| GSS code | E09000030 |

| Police | Metropolitan Police |

| Website | www |

The borough lies adjacent to the east side of the City of London and on the north bank of the River Thames. It includes much of the redeveloped Docklands region of London, including West India Docks and Canary Wharf. Many of the tallest buildings in London occupy the centre of the Isle of Dogs in the south of the borough. A part of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park is in Tower Hamlets. The borough has a population of 272,890,[2] which includes one of the highest Muslim populations in the country and has an established British Bangladeshi business and residential community. Tower Hamlets has the highest proportion of Muslims in England outnumbering Christians, and has more than forty mosques and Islamic centres,[3] including the East London Mosque, Britain's biggest mosque.[4] Brick Lane's restaurants, neighbouring street market and shops provide the largest range of Bengali cuisine, woodwork, carpets and clothes in Europe.[5][6]

A 2017 study by Trust for London and New Policy Institute[7][8] found that Tower Hamlets has the highest rate of poverty, child poverty, unemployment, and pay inequality of any London borough. However, it has the lowest gap for educational outcomes at secondary level.[9] The local authority is Tower Hamlets London Borough Council. As of January 2019, the councillors are: 42 Labour, 2 Conservative and 1 Liberal Democrat.[10]

Geography

Physical geography

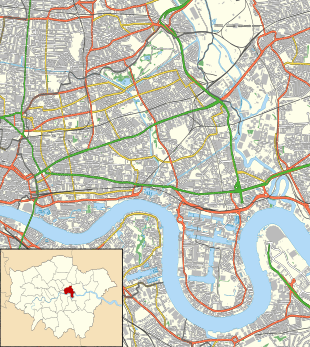

Tower Hamlets is located east of the City of London and north of the River Thames in East London. The London Borough of Hackney lies to the north of the borough while the River Lea forms the boundary with the London Borough of Newham in the east. On the other side of the Thames is The London Borough of Southwark to the southwest, The London Borough of Lewisham to the South, and The Royal Borough of Greenwich to the southeast. The River Lea also forms the boundary between those parts of London historically in Middlesex, with those formerly in Essex.

The Isle of Dogs is formed from the lock entrances to the former West India Docks and the largest current meander of the River Thames and the southern part of the borough forms a part of the historic flood plain of the River Thames;[11] and but for the Thames Barrier and other flood prevention works would be vulnerable to flooding.

The Regent's Canal enters the borough from Hackney to meet the River Thames at Limehouse Basin. A stretch of the Hertford Union Canal leads from the Regent's canal, at a basin in the north of Mile End to join the River Lea at Old Ford. A further canal, Limehouse Cut, London's oldest, leads from locks at Bromley-by-Bow to Limehouse Basin. Most of the canal tow-paths are open to both pedestrians and cyclists.

Victoria Park was formed by Act of Parliament, and administered by the LCC and its successor authority the GLC. Since the latter authority's abolition, the park has been administered by Tower Hamlets. Part of the borough is within the boundary of the Thames Gateway development area.

in the Borough of Tower Hamlets.

Wards within the borough

As of 2014, Tower Hamlets is divided in to 20 wards, increased from 17 previously. These are:[12]

- Bethnal Green

- Blackwall and Cubitt Town

- Bow East

- Bow West

- Bromley North

- Bromley South

- Canary Wharf

- Island Gardens

- Lansbury

- Limehouse

- Mile End

- Poplar

- Shadwell

- Spitalfields and Banglatown

- St Dunstan's

- St Katharine's and Wapping

- St Peter's

- Stepney Green

- Weavers

- Whitechapel

History

The earliest reference to the name "Tower Hamlets" was in 1554, when the Council of the Tower of London ordered a muster of "men of the hamlets which owe their service to the tower". This covered a wider area than the present-day borough. In 1605, the Lieutenant of the Tower was given the right to muster the militia, which led to the area east of the tower to be a distinct military unit, officially called Tower Hamlets (or the Tower Division).[13] The Hamlets of the Tower paid taxes for the militia in 1646.[14]

The London Borough of Tower Hamlets forms the core of the East End. It lies east of the ancient walled City of London and north of the River Thames. Use of the term "East End" in a pejorative sense began in the late 19th century,[15] as the expansion of the population of London led to extreme overcrowding throughout the area and a concentration of poor people and immigrants in the districts that made it up.[16] These problems were exacerbated with the construction of St Katharine Docks (1827)[17] and the central London railway termini (1840–1875) that caused the clearance of former slums and rookeries, with many of the displaced people moving into the area. Over the course of a century, the East End became synonymous with poverty, overcrowding, disease and criminality.[18]

The East End developed rapidly during the 19th century. Originally it was an area characterised by villages clustered around the City walls or along the main roads, surrounded by farmland, with marshes and small communities by the River, serving the needs of shipping and the Royal Navy. Until the arrival of formal docks, shipping was required to land goods in the Pool of London, but industries related to construction, repair, and victualling of ships flourished in the area from Tudor times. The area attracted large numbers of rural people looking for employment. Successive waves of foreign immigration began with Huguenot refugees creating a new extramural suburb in Spitalfields in the 17th century.[19] They were followed by Irish weavers,[20] Ashkenazi Jews[21] and, in the 20th century, Bangladeshis.[22] Many of these immigrants worked in the clothing industry. The abundance of semi- and unskilled labour led to low wages and poor conditions throughout the East End. This brought the attentions of social reformers during the mid-18th century and led to the formation of unions and workers associations at the end of the century. The radicalism of the East End contributed to the formation of the Labour Party and demands for the enfranchisement of women.

Official attempts to address the overcrowded housing began at the beginning of the 20th century under the London County Council. World War II devastated much of the East End, with its docks, railways and industry forming a continual target, leading to dispersal of the population to new suburbs, and new housing being built in the 1950s.[18] During the war, in the Boroughs making up Tower Hamlets a total of 2,221 civilians were killed and 7,472 were injured, with 46,482 houses destroyed and 47,574 damaged.[23] The closure of the last of the East End docks in the Port of London in 1980 created further challenges and led to attempts at regeneration and the formation of the London Docklands Development Corporation. The Canary Wharf development, improved infrastructure, and the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park[24] mean that the East End is undergoing further change, but some of its districts continue to contain some of the worst poverty in Britain.[25]

Coat of Arms

The coat of arms of the modern Borough of Tower Hamlets was granted by the College of Arms in 1965[26] and comprises a number of elements representing the trade and heritage of the area, particularly the link to the maritime trades and the strong links to the former Manor and Ancient Parish of Stepney, an area which included much or all of the area of the current borough. These are connected, with St Dunstan's church in Stepney known as the Church of the High Seas. The Manor and Parish did not have a coat of arms but the (smaller) subsequent Metropolitan Borough of Stepney did, and extensive use has been made of elements of that.

The Shield features:

- Ship, representing the maritime trades.

- Sprig of mulberry and a weaver's shuttle, representing the silk and other weaving activities once so important to the borough.

- Blacksmiths fire tongs, the emblem of St Dunstan, the patron saint of Stepney, who had close ties to the area. Dunstan famously grabbed the devil by the nose with his tongs when he tried to tempt Dunstan.

The crest features:

- A silver representation of the (originally whitewashed) White Tower of the Tower of London, to which the original Tower Hamlets (or Tower division) was intimately linked.

- Crossed gold anchors, again representing the areas position in the Port of London.

Supporters:

- Seahorse, representing the maritime trades.

- Talbot dog, representing the Isle of Dogs.

Motto: From great things to greater, an anglicised version of the Latin motto on the arms of the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney.

The Council's logo is used as an alternative to the coat of arms. It features a simplified White Tower, above a stylised representation of the Thames in the area. This was a development of the previous logo of the White Tower, in mulberry (claret) and presented in a three-tower form, as if seen from certain quarters which obscured the furthest corner tower - and a geographically accurate representation of the local part of the Thames. This older version is still seen on many street signs.

Politics

Parliament

For the 2017 general election, the borough was split into two constituencies:

- Bethnal Green & Bow, represented by Rushanara Ali (Labour)

- Poplar & Limehouse, represented by Apsana Begum (Labour)

Until the United Kingdom left the European Union, the borough was a part of the London constituency for elections to the European Parliament. Labour has dominated national elections in Tower Hamlets, although other left-wing parties have won seats including the Respect Unity coalition in 2005 in Bethnal Green & Bow.

London Assembly

The borough lies within the City and East constituency, one of fourteen constituencies which make up the London Assembly, and is represented by John Biggs of the Labour Party.

London Borough Council

The Labour Party has dominated politics in Tower Hamlets since the borough was first created in 1965 except for a period from 1986 to 1994 when the SDP–Liberal Alliance and then the Liberal Democrats controlled the council. The British National Party won its first council seat in 1993, when Derek Beackon was elected as a Millwall councillor.[27]

In May 2010, a referendum led to the creation of a directly elected executive Mayor for the Borough. At the ensuing election in October 2010, Lutfur Rahman was elected Mayor as an independent candidate, becoming the UK's first Muslim executive mayor.[28] Rahman had been selected as the Labour candidate for Mayor, and was a former Leader of the Council. However, allegations of electoral malpractice were made against him and his supporters, and he was suspended from the Labour Party before nominations closed.[29] He was re-elected as Mayor in May 2014.[30]

At the May 2010 election, the composition of the Council was 41 Labour, 8 Conservative, 1 Respect and 1 Liberal Democrat councillor. Since then, Respect gained a seat from Labour at a by-election, and in three separate groups a total of 8 Labour Councillors and one Conservative defected to Lutfur Rahman's independent group.

This shifting of political allegiances is normal for Tower Hamlets. Between the 2006 and 2010 elections, five Respect councillors defected to Labour; one Respect and one Labour councillor defected to the Conservatives; one Liberal Democrat defected to Labour; and one Labour councillor was gained through a by-election at the expense of the Liberal Democrats.[31]

In July 2013, the Tower Hamlets (Electoral Changes) Order 2013 was passed,[32] reducing the size of the Council and creating new electoral wards made of single, two- and 3-member divisions.

In September 2013, Lutfur Rahman's independent group was officially renamed Tower Hamlets First. At the May 2014 election, the group made significant gains by winning 18 of the 45 seats, which reduced the previously Labour-held council to No Overall Control.[33] Labour remains the largest group with 22 councillors (notionally down 14), while the Conservatives have 5 seats (down 6).[34] Both the Liberal Democrats and Respect Party were wiped out at this election.

In November 2014, the Department for Communities and Local Government announced that they would appoint commissioners to take over some of the council's functions, following an inspection report[35] by PricewaterhouseCoopers that raised several concerns over the allocation of grants.[36] The action was supported by the Department's shadow secretary, Hilary Benn.[37]

On 23 April 2015, the courts removed Mayor Rahman from office for electoral fraud and ordered a new election to be held.[38] Six days later, the Electoral Commission officially withdrew Rahman's Tower Hamlets First from the electoral register, after deciding that the party did not operate a responsible financial scheme, nor ran in accordance with its initial documentation provided at registration.[39] The decision renders the former group members as Independent councillors. On 11 June 2015, Labour candidate John Biggs was elected mayor, while a Labour win at a by-election enabled the party to regain overall control of the Council.[40]

Since 2014, the council has embraced a policy of decentralisation by establishing neighbourhood forums in different areas. In 2014, the East Shoreditch Neighbourhood Planning Forum was set up which was followed in 2016 with the designation of Limehouse Community Forum, Isle of Dogs Neighbourhood Planning Forum and Spitalfields Neighbourhood Planning Forum.

Local landmarks

Historical landmarks

- Brick Lane

- Cable Street - site of the Battle of Cable Street

- East Smithfield

- Fish Island

- Hawksmoor's Christ Church, Spitalfields

- Site of two historic Royal Mints

- Tower of London

- Tower Bridge

- Victoria Park

- Roman Road

- Columbia Road

- Poplar Baths

Modern landmarks

The Canary Wharf complex within Docklands on the Isle of Dogs forms a group of some of the tallest buildings in Europe. One Canada Square was the first to be constructed and is the second tallest in London. Nearby are the HSBC Tower, Citigroup Centres and One Churchill Place, headquarters of Barclays Bank. Within the same complex are the Heron Quays offices.

Part of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, developed for the London 2012 Olympics, lies within the borders of Tower Hamlets.

Climate

The data below were taken between 1971 and 2000 at the weather station in Greenwich, around 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the town hall, at Mulberry Place:

| Climate data for Greenwich Park, elevation: 47 m (154 ft), 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

37.5 (99.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.3 (52.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

5.8 (42.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.4 (15.1) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.6 (1.64) |

36.3 (1.43) |

40.3 (1.59) |

40.1 (1.58) |

44.9 (1.77) |

47.4 (1.87) |

34.6 (1.36) |

54.3 (2.14) |

51.0 (2.01) |

61.1 (2.41) |

57.5 (2.26) |

48.4 (1.91) |

557.4 (21.94) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.4 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 9.5 | 109.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 44.7 | 65.4 | 101.7 | 148.3 | 170.9 | 171.4 | 176.7 | 186.1 | 133.9 | 105.4 | 59.6 | 45.8 | 1,410 |

| Source 1: Met Office[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BBC Weather[44] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 130,871 | — |

| 1811 | 160,718 | +22.8% |

| 1821 | 195,941 | +21.9% |

| 1831 | 231,534 | +18.2% |

| 1841 | 275,250 | +18.9% |

| 1851 | 330,548 | +20.1% |

| 1861 | 410,101 | +24.1% |

| 1871 | 489,653 | +19.4% |

| 1881 | 569,205 | +16.2% |

| 1891 | 584,936 | +2.8% |

| 1901 | 578,143 | −1.2% |

| 1911 | 571,438 | −1.2% |

| 1921 | 529,114 | −7.4% |

| 1931 | 489,956 | −7.4% |

| 1941 | 337,774 | −31.1% |

| 1951 | 232,860 | −31.1% |

| 1961 | 195,883 | −15.9% |

| 1971 | 164,699 | −15.9% |

| 1981 | 139,989 | −15.0% |

| 1991 | 167,985 | +20.0% |

| 2001 | 196,121 | +16.7% |

| 2011 | 254,096 | +29.6% |

| 2016 | 304,900 | +20.0% |

| Note:[45] | ||

By 1891, Tower Hamlets – roughly the civil parish of Stepney – was already one of the most populated areas in London. Throughout the nineteenth century, the local population increased by an average of 20% every ten years. The building of the docks intensified land use and caused the last marshy areas in the south of the parish to be drained for housing and industry. In the north of the borough, employment was principally in weaving, small household industries like boot and furniture making and new industrial enterprises like Bryant and May. The availability of cheap labour drew in many employers. To the south of the parish, employment was in the docks and related industries – such as chandlery and rope making.

By the middle of the century, the district of Tower Hamlets was characterised by overcrowding and poverty. The construction of the railways caused many more displaced people to settle in Tower Hamlets, and a massive influx of Eastern European Jews at the end of the nineteenth century added to the population growth. This influx peaked at the end of the century and population growth entered a long decline through to the 1960s, as they moved away eastwards to newer suburbs of London in Essex. The area's population had neared 600,000 around the end of the 19th century, but fell to a low of less than 140,000 by the early 1980s.

The metropolitan boroughs suffered very badly during World War II, during which considerable numbers of houses were destroyed or damaged beyond use due to heavy aerial bombing. This coincided with a decline in work in the docks, and the closure of many traditional industries. The Abercrombie Plan for London (1944) began an exodus from London towards the new towns.[46]

This decline began to reverse with the establishment of the London Docklands Development Corporation bringing new industries and housing to the brownfield sites along the river. Also contributing was new immigration from Asia beginning in the 1970s. According to the 2001 UK Census the population of the borough is approximately 196,106. According to the ONS estimate, the population is 237,900, as of 2010.[47]

Crime in the borough increased by 3.5% from 2009–2010, according to figures from the Metropolitan Police,[48] having decreased by 24% between 2003/04 and 2007/08.[49]

Tower Hamlets has one of the smallest White British populations of any local authority in the United Kingdom. No ethnic group forms a majority of the population; a plurality of residents are white (45%), of which only 69% (from a total of 31% of the entire population) are indigenous White British. Asians form 41% of the population, of which 32% are Bangladeshi; which is the largest ethnic minority group in the borough.[50][51] A small proportion are of Black African and Caribbean descent (7%),[50] with Somalis representing the second-largest minority ethnic group.[52] Those of mixed ethnic backgrounds form 4%, while other ethnic groups form 2%.[50][52][53] The indigenous proportion was recorded as 31.2% in the 2011 UK Census, a decrease from 42.9% in 2001.

In 2018, Tower Hamlets had the lowest life expectancy and the highest rate of heart disease of all London boroughs, along with Newham.[54]

Ethnicity

| Ethnic Group | 2001[55] | 2011[56] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: British | 84,151 | 43% | 79,231 | 31% |

| White: Irish | 3,823 | 2% | 3,863 | 2% |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | 175 | 0% | ||

| White: Other | 12,825 | 7% | 31,550 | 12% |

| White: Total | 100,799 | 51% | 114,819 | 45% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 3,001 | 2% | 6,787 | 3% |

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 1,486 | 1% | 2,442 | 1% |

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 65,553 | 33% | 81,377 | 32% |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 3,573 | 2% | 8,109 | 3% |

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | 1,767 | 1% | 5,786 | 2% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 75,380 | 38% | 104,501 | 41% |

| Black or Black British: African | 6,596 | 3% | 9,495 | 4% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | 5,225 | 3% | 5,341 | 2% |

| Black or Black British: Other Black | 921 | 0% | 3,793 | 1% |

| Black or Black British: Total | 12,742 | 6% | 18,629 | 7% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | 1,568 | 1% | 2,837 | 1% |

| Mixed: White and Black African | 789 | 0% | 1,509 | 1% |

| Mixed: White and Asian | 1,348 | 1% | 2,961 | 1% |

| Mixed: Other Mixed | 1,168 | 1% | 3,053 | 1% |

| Mixed: Total | 4,873 | 2% | 10,360 | 4% |

| Other: Arab | 2,573 | 1% | ||

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 2,312 | 1% | 3,214 | 1% |

| Other: Total | 2,312 | 1% | 5,787 | 3% |

| Black, Asian, and minority ethnic: Total | 95,307 | 49% | 139,277 | 55% |

| Total | 196,106 | 100.00% | 254,096 | 100.00% |

Religious sites

As Tower Hamlets is considered one of the world's most racially diverse zones, it holds various places of worship. According to the 2011 census, 34.5% of the population was Muslim, 27.1% Christian, 1.7% Hindu, 1.1% Buddhist, 1.1% followed another religions (including Judaism, Sikhism and Jedi), 19.1% were not affiliated to a religion and 15.4% did not state their religious views.[58]

There are 21 active churches, affiliated with the Church of England, which include Christ Church of Spitalfields, St Paul's Church of Shadwell and St Dunstan's of Stepney[59] and also churches of many other Christian denominations.

There are more than 40 mosques and Islamic centres in Tower Hamlets.[3] The most famous is the East London Mosque, one of the first mosques in Britain allowed to broadcast the adhan[4] and one of the biggest Islamic centres in Europe. The Maryam Centre, a part of the mosque, is the biggest Islamic centre for women in Europe. Opened in 2013, it features a main prayer hall, ameliorated funeral services, education facilities, a fitness centre and support services.[60][61][62] The East London Mosque has been visited by several notable people, including Prince Charles, Boris Johnson, many foreign government officials and world-renowned imams and Muslim scholars.[63] Other notable mosques are Brick Lane Mosque, Darul Ummah Masjid, Esha Atul Islam Mosque, Markazi Masjid, Stepney Shahjalal Mosque and Poplar Central Mosque.[64]

Other notable religious buildings include the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue, the Congregation of Jacob Synagogue, the London Buddhist Centre, the Hindu Pragati Sangha Temple, and the Gurdwara Sikh Sangat.

religion in Tower Hamlets as of 2011

Economy

The borough hosts the world headquarters of many global financial businesses, employing some of the highest paid workers in London, but also has a high rates of long-term illness and premature death and the 2nd highest unemployment rate in London.[65]

Canary Wharf is home to the world or European headquarters of numerous major banks and professional services firms including Barclays, Citigroup, Clifford Chance, Credit Suisse, Infosys, Fitch Ratings, HSBC, J.P. Morgan, KPMG, MetLife, Morgan Stanley, RBC, Skadden, State Street and Thomson Reuters.[66] Savills, a top-end estate agency recommends that 'extreme luxury' and ultra-modern residential properties are to be found at Canary Riverside, West India Quay, Pan Peninsula and Neo Bankside.

The End Child Poverty coalition published that Tower Hamlets has the highest proportion of children in poverty of any local authority in the UK at 49% (and as high as 54.5% in the Bethnal Green South ward).[67]

Surveys and interviews conducted by the Child Poverty Action group for the council found that the Universal Credit system was deeply unpopular with low-income families in the borough and that most claimants who have used the system found it difficult to understand and experienced frequent payment errors.[68]

Education

The London Borough of Tower Hamlets is the local education authority for state schools within the borough.[69] In January 2008, there were 19,890 primary-school pupils and 15,262 secondary-school pupils attending state schools there.[70] Independent-school pupils account for 2.4 per cent of schoolchildren in the borough.[71] In 2010, 51.8 per cent of pupils achieved 5 A*–C GCSEs including Mathematics and English — the highest results in the borough's history — compared to the national average of 53.4 per cent.[72] Seventy-four per cent achieved 5 A*–C GCSEs for all subjects (the same as the English average);[73] the figure in 1997 was 26 per cent.[74] The percentage of pupils on free school meals in the borough is the highest in England and Wales.[75] In 2007 the council rejected proposals to build a Goldman Sachs-sponsored academy.[76]

Schools in the borough have high levels of racial segregation. The Times reported in 2006 that 47 per cent of secondary schools were exclusively non-white, and that 33 per cent had a white majority.[77] About 60 per cent of pupils entering primary and secondary school are Bangladeshi.[78] 78% of primary-school pupils speak English as a second language.[79]

The council runs several Idea Stores in the borough, which combine traditional library and computer services with other resources, and are designed to attract more diverse members.[80] The flagship Whitechapel store was designed by David Adjaye[81] and cost £16 million to build.[82]

Universities

- Queen Mary University of London, a constituent college of the University of London, which includes Barts and The London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry

- London Metropolitan University

- UCL School of Management, located in One Canada Square, Canary Wharf

Further education colleges

- Tower Hamlets College, which in 2017 merged with Hackney Community College and Redbridge College to form New City College, the second largest college in London with over 20,000 students.[83]

Schools and Sixth form colleges

- Bethnal Green Academy

- Bishop Challoner Catholic Collegiate School

- Bow School

- Central Foundation Girls' School

- George Green's School

- Lansbury Lawrence School

- Langdon Park School

- Morpeth School

- Mulberry School for Girls

- Oaklands School

- Raine's Foundation School

- Sir John Cass Redcoat School

- St Paul's Way Trust School

- Stepney Green Maths, Computing & Science College

- Swanlea School, Business and Enterprise College

- Jamiatul Ummah School and Sixth Form

- London East Academy (East London Mosque)

- Ibrahim College

- London Enterprise Academy

- Wapping High School

- Mazahirul uloom London

Volunteering

- Volunteer Centre Tower Hamlets helps residents find volunteering work and provides support to organisations involving students volunteers.[84]

Sports

Mile End Stadium within Mile End Park hosts an athletics stadium and facilities for football and basketball. Two football clubs, Tower Hamlets F.C. (formerly Bethnal Green United) and Sporting Bengal United F.C., are based there, playing in the Essex Senior Football League.

John Orwell Sports Centre in Wapping is the base of Wapping Hockey Club. In 2014, the club secured over £300,000 of investment to designate the centre a hockey priority facility.[85]

A leisure centre including a swimming pool at Mile End Stadium was completed in 2006. Other pools are located at St Georges, Limehouse and York Hall, in Bethnal Green. York Hall is also a regular venue for boxing tournaments, and in May 2007 a public spa was opened in the building's renovated Turkish baths.[86]

KO Muay Thai Gym[87] and Apolaki Krav Maga & Dirty Boxing Academy.[88] in Bethnal Green are the main sources for martial arts and combat sports training in the area.

The unusual Green Bridge, opened in 2000, links sections of Mile End Park that would otherwise be divided by Mile End Road. The bridge contains gardens, water features and trees around the path.[89]

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

Tower Hamlets was one of five host boroughs for the 2012 Summer Olympics;[90] the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park was constructed in the Lea Valley. As such, the borough's involvement in the Olympics includes:

- A small part of the Olympic Park is in Bow, a district of the borough, which makes the borough a host borough.

- The energy centre (King's Yard Energy Centre) of the Olympic Park is in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, and gives energy to all the venues, none of which are located in Tower Hamlets.

- The world square and the London 2012 mega-store is also in the borough. The world square is for spectators, who can buy food or drink; the world's biggest McDonald's is in the world square in Tower Hamlets.

- The London 2012 mega-store provides official gifts and souvenirs. High Street, which is the main road to the Olympic park from west and central London, combines Whitechapel Road, Mile End Road and Bow Road.

- Victoria Park, in Tower Hamlets, is an important part of the Olympics because spectators without tickets can watch the games on big screens (London live 2012); that park is less than a mile away from the Olympic park. The main spectator cycle park is located in Victoria park. One of the entrances to the Olympic park is in Tower Hamlets, and is called the Victoria gate.

- A few schools in Tower Hamlets have taken part in the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympic and Paralympic games as well as all the other host boroughs. The section of the Olympic Park in Tower Hamlets will be named "Sweetwater", one of the 5 new neighbourhoods after the games. Sweetwater will cover Tower Hamlets' part of the Olympic Park near Old Ford.

- The Olympic marathon was planned to run through the borough but later ran through the City and Westminster. However, the U-turn was located in the borough near The Tower of London.

- Danny Boyle, the artistic director of the London 2012 opening ceremony, lives in Mile End.

- A large number of Tower Hamlets' residents became Olympic volunteers; Tower Hamlets ranks second, after neighbouring borough Newham, for the number of volunteers from the borough.

Leisure

Parks in Tower Hamlets

There are over one hundred parks and open spaces in Tower Hamlets ranging from the large Victoria Park, to numerous small gardens and squares. The second largest, Mile End Park, separated from Victoria Park by a canal, includes The Green Bridge that carries the park across the busy Mile End Road. One of the smallest at 1.19 ha is the decorative Grove Hall Park off Fairfield Road, Bow, which was once the site of a lunatic asylum.[91] Other parks include Altab Ali Park, Mudchute Park and Grove Hall Park.

Museums

- Island History Trust

- Museum of London Docklands

- Ragged School Museum

- V&A Museum of Childhood

- Whitechapel Art Gallery

Transport

Road

As with most of the transport network in Tower Hamlets, several roads radiate across the Borough from the City of London.[92] East-west routes include:

- the A11, which runs from Aldgate to the A12 near Stratford, passing through Whitechapel, Mile End, and Bow.

- the A13 (Commercial Road/East India Dock Road), which runs from Aldgate to Poplar. East of Poplar, the route continues towards Barking, Tilbury, and Southend.

- the A1203 (The Highway), which runs from Tower Hill, through Wapping, to Limehouse and Canary Wharf.

There are several north-south routes in the Borough,[92] including:

- the A12, which begins at the A13 in Poplar and runs along the eastern edge of the Borough. The route carries traffic towards the M11 (for Stansted Airport

- the London Inner Ring Road from Old Street to Tower Bridge.

There are three River Thames road crossings in the Borough.[92] From west-east, these are:

- Tower Bridge (Tower Hill to Southwark and Bermondsey)

- Rotherhithe Tunnel (the A13 at Limehouse to Canada Water)

- Blackwall Tunnel (the A12 and A13 at Poplar to Greenwich)

Rail

The principal rail services commence in the City at Fenchurch Street, with one stop at Limehouse; and Liverpool Street, with stops at Bethnal Green and Cambridge Heath. The East London Line passes from north to south through Tower Hamlets with stations at Whitechapel, Shadwell and Wapping. One entrance to Shoreditch High Street station is inside the Borough. And the North London Line passes the very north in Tower Hamlets with one entrance to Hackney Wick inside the Borough. Two Crossrail stations are currently under construction and are expected to start services in late 2018.

- Metro

The Docklands Light Railway was built to serve the docklands areas of the borough, with a principal terminus at Bank and Tower Gateway. An interchange at Poplar allows trains to proceed north to Stratford, south via Canary Wharf towards Lewisham, and east either via the London City Airport to Woolwich Arsenal or via ExCeL London to Beckton.

Three London Underground services cross the district, serving a total of 8 stations: the District and Hammersmith and City lines share track between Aldgate East and Barking. The Central line has stations at Bethnal Green and Mile End - where there is an interchange to the District line. A third central line station, at Shoreditch, has been proposed as the Central line runs within close proximity of Shoreditch High Street station. If built, it will be situated between the existing stations at Bethnal Green and Liverpool St. The Jubilee line has one stop at Canary Wharf.

List of stations

- Aldgate East station

- All Saints DLR station

- Bethnal Green railway station

- Bethnal Green tube station

- Blackwall DLR station

- Bow Church station

- Bow Road station

- Bromley-by-Bow station

- Cambridge Heath railway station

- Canary Wharf DLR station

- Canary Wharf tube station

- Crossharbour DLR station

- Devons Road DLR station

- East India DLR station

- Hackney Wick railway station

- Heron Quays DLR station

- Island Gardens DLR station

- Langdon Park DLR station

- Limehouse station (Rail and DLR)

- Mile End station

- Mudchute DLR station

- Poplar DLR station

- Shadwell railway station

- Shadwell DLR station

- Shoreditch High Street railway station

- South Quay DLR station

- Stepney Green tube station

- Tower Gateway DLR station

- Tower Hill tube station

- Wapping railway station

- West India Quay DLR station

- Westferry DLR station

- Whitechapel tube station

- Whitechapel railway station

In March 2011, the main forms of transport that residents used to travel to work were: underground, light rail, 24.0% of all residents aged 16–74; on foot, 7.5%; bus, minibus or coach, 7.5%; driving a car or van, 6.9%; bicycle, 4.1%; train, 3.8%; work mainly at or from home, 2.3%.[93]

Tower Hamlets Borough Council operates a walking bus service for school students on agreed routes with some running every school day while and others once or twice a week depending on the number of adult volunteers involved.[94]

Freedom of the Borough

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the Borough of Tower Hamlets.

Military Units

- HMS Crane, RN: 1942.

- 114 (1st London) Army Engineer Regiment (TA): 27 April 1961. [96]

See also

References

Citations

- 2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in England and Wales, Office for National Statistics (2012). See Classification of ethnicity in the United Kingdom for the full descriptions used in the 2011 Census.

- 2013 Mid Year Estimates "UK Population Estimates" Archived 10 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. ONS. Retrieved 27 June 2014

- "Bangla Stories". banglastories.org.

- Eade, John (1996). "Nationalism, Community, and the Islamisation of Space in London". In Metcalf, Barbara Daly (ed.). Making Muslim Space in North America and Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520204042. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

As one of the few mosques in Britain permitted to broadcast calls to prayer (azan), the mosque soon found itself at the centre of a public debate about “noise pollution” when local non-Muslim residents began to protest.

- Garbin, David. "Bangladeshi diaspora in the UK: some observations on socio-cultural dynamics, religious trends and transnational politics", Conference Human Rights and Bangladesh, School of African and Oriental Studies, June 2005, p. 1. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Tower Hamlets Council Corporate Research Unit, Religion in Tower Hamlets 2011 Census: Key Facts (Briefing 2013-03) Archived 5 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "London Poverty & Inequality, London Living Wage - Trust For London". Trust for London.

- "Home". www.npi.org.uk.

- "London's Poverty Profile". Trust for London. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "Your Councillors". Democracy.towerhamlets.gov.uk. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "BBC on Thames floodplain", BBC News. Retrieved 31 March 2007.

- "Tower Hamlets Area Profiles 2014". Tower Hamlets. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 923.

- 1648 Ordinance for Militia within the Hamblets of the Tower of London British History Online

- East End 1888 William Fishman (1998) p.1

- From 1801 to 1821, the population of Bethnal Green more than doubled, and by 1831 had trebled (see table in population section). These incomers were principally weavers. For further details, see Andrew August Poor Women's Lives: Gender, Work, and Poverty in Late-Victorian London pp 35-6 (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1999) ISBN 0-8386-3807-4

- By the early 19th century, over 11,000 people were crammed into insanitary slums in an area, which took its name from the former Hospital of St Catherine that had stood on the site since the 12th century.

- The East End Alan Palmer, (John Murray, London 1989) ISBN 0-7195-5666-X

- Bethnal Green: Settlement and Building to 1836, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 91–5 Date accessed: 17 April 2007

- Irish in Britain John A. Jackson, p. 137–9, 150 (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1964)

- The Jews, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 1: Physique, Archaeology, Domesday, Ecclesiastical Organization, The Jews, Religious Houses, Education of Working Classes to 1870, Private Education from Sixteenth Century (1969), pp. 149–51 Date accessed: 17 April 2007

- The Spatial Form of Bangladeshi Community in London's East End Iza Aftab (UCL) (particularly background of Bangladeshi immigration to the East End). Date accessed: 17 April 2007

- The East End at War Rosemary Taylor and Christopher Lloyd (Sutton Publishing, 2007) ISBN 0-7509-4913-9

- Olympic Park: Legacy Archived 20 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine (London 2012) accessed 20 September 2007

- Chris Hammett Unequal City: London in the Global Arena (2003) Routledge ISBN 0-415-31730-4

- Heraldry of the World website https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/heraldrywiki/index.php?title=Tower_Hamlets

- "1993: Shock as racist wins council seat", BBC News. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Hill, Dave. "Britain's first Muslim executive mayor vows to 'reach out to every community'", The Guardian, 8 November 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Hill, Dave. "Tower Hamlets: Lutfur Rahman removed as Labour mayoral candidate", The Guardian, 21 September 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- "Lutfur Rahman mobbed by supporters on re-election". BBC. 24 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- LBTH ward details Archived 10 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine accessed 21 May 2010

- "The Tower Hamlets (Electoral Changes) Order 2013". Legislation.gov.uk.

- "Tower Hamlets". bbc.co.uk.

- "Tower Hamlets Council - Election results by party, 22 May 2014". towerhamlets.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- "Best Value Inspection of London Borough of Tower Hamlets Report" (PDF). Gov.uk. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Mason, Tania (4 November 2014). "Tower Hamlets grants-for-votes inquiry finds grant guidelines were flouted". Civil Society. London. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- Wright, Oliver (4 November 2014). "Eric Pickles sends hit squad to tackle 'rotten borough' of Tower Hamlets". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "Tower Hamlets election fraud mayor Lutfur Rahman removed from office". BBC News. 23 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "Electoral Commission - Media statement on removal of Tower Hamlets First from the Electoral Commission's register of political parties". Electoralcommission.org.uk.

- "Tower Hamlets election: Labour's John Biggs named mayor". BBC. 12 June 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- "Greenwich 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Hot Spell - August 2003". Met Office. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Record Breaking Heat and Sunshine - July 2006". Met Office. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "London Forecast". Met Office. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Tower Hamlets: Total Population". A Vision of Britain Through Time. Great Britain Historical GIS Project. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- A Vision of Britain through time. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Resident Population Estimates, All Persons - Tower Hamlets ONS.

- Kleebauer, Alistair. "Crime went up by 3.5% in Tower Hamlets last year, according to Met figures". East London Advertiser. 23 January 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011. Archived 21 July 2011.

- "Tower Hamlets Crime and Drugs Reduction Strategy – Year 1 2008/09" Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Tower Hamlets Partnership. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Ethnicity in Tower Hamlets TowerHamlets.gov.uk.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Audit Commission" (PDF). audit-commission.gov.uk.

- Neighbourhood Statistics. "Tower Hamlets - Ethnic groups - 2001 Census - ONS". Neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- "Diabetes and heart disease in Bangladeshis and Pakistanis | East London Genes & Health". Genesandhealth.org (in Bengali). Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "KS006 - Ethnic group". Nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Ethnic Group by measures". Nomisweb.co.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Eade, John (1996). "Nationalism, Community, and the Islamization of Space in London". In Metcalf, Barbara Daly (ed.). Making Muslim Space in North America and Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520204042. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

The mosque committee was determined from the outset, moreover, to remind local people of the building’s religious function as loudly as possible. As one of the few mosques in Europe permitted to broadcast calls to prayer (azan), the mosque soon found itself at the center of a public debate about “noise pollution” when local non-Muslim residents began to protest.

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Tower Hamlets Local Authority (1946157257)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Church List: Tower Hamlets The Diocese of London. Retrieved on 27 March 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 August 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Islamic Forum of Europe". islamicforumeurope.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Prince joins Ramadan ceremony BBC website

- Mosques in Tower Hamlets, Muslimsinbritain.org. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "Poverty Indicator - Tower Hamlets". Londons Poverty Profile.

- "China to invest in Canary Wharf". China Economic Review. 31 August 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- "Poverty in your area". End Child Poverty. October 2014. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- Butler, Patrick (16 October 2019). "Universal credit 'leaving families depressed' in poorest London borough". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- See list of education authority schools Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Pupil projections" Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Tower Hamlets Council. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- See also: "DfE: Schools, Pupils and their Characteristics, January 2011", Department for Education, data released on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "Private schools: capital spending", The Economist, 22 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011. Archived 11 July 2011.

- "Secondary schools and colleges in Tower Hamlets", BBC News, 12 January 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011. See also:

- "Guide: Secondary league tables", BBC News, 12 January 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- "Tower Hamlets: GCSE and A-level results for 2009-2010", The Guardian, 12 January 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- For highest results, see: "Tower Hamlets scores record GCSE results", Tower Hamlets London Borough Council, 25 August 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2010. Archived 11 July 2011.

- GCSE information (XLS) (364 KB). Department for Education. Table 16. 21 October 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2011. See publication page.

- Cavendish, Camilla. "You don't need the middle class". The Times. 4 March 2003. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Attainment at age 11 by borough", londonspovertyprofile.org.uk, 13 July 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Garner, Richard. "Tower Hamlets rejects Goldman Sachs' offer to sponsor academy", The Independent, 21 June 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Frean, Alexandra. "Race quotas 'needed to end divide in schools'". The Times. 12 October 2006. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- See also: "Schools in the East End dividing by race". Evening Standard. 29 May 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Johnston, Ron; Burgess, Simon; Harris, Richard; Wilson, Deborah. "'Sleep-Walking Towards Segregation?' The Changing Ethnic Composition of English Schools, 1997-2003: An Entry Cohort Analysis". Centre for Market and Public Organisation. University of Bristol. September 2006. p. 6.

- "More pupils can claim free meals", BBC News, 11 August 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Jeffrey Schnapp; Matthew Battles (2014). Library Beyond the Book. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72503-4.

- Sudjic, Deyan. "Just give him some space". The Guardian. 6 November 2005. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Administration and Maintenance". Idea Store. Retrieved 21 July 2011. Archived 21 July 2011.

- "New City College". Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Volunteer Centre Tower Hamlets". Vcth.org.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- Gilmour, Rod (3 March 2014) "Wapping's Hockey Revolution Bears Fruits as London Club Goes Business Savvy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved on 24 August 2014.

- "Spa London, Bethnal Green - 3 bubbles", The Good Spa Guide. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "KO Gym - Combat Academy - Muay Thai - Kick Boxing - London". Komuaythai.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "History and Background" Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Tower Hamlets London Borough Council. Retrieved 21 July 2011. See PDF files.

- "The 2012 Olympics: The greatest sideshow on Earth", The Economist, 22 July 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Tower Hamlets Council. AZ of Parks. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "London Borough of Tower Hamlets". OpenStreetMap.

- "2011 Census: QS701EW Method of travel to work, local authorities in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 23 November 2013. Percentages are of all residents aged 16-74 including those not in employment. Respondents could only pick one mode, specified as the journey’s longest part by distance.

- "Cycling and walking to school". Towerhamlets.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- https://www.eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk/news/queen-s-deputy-lieutenant-john-ludgate-receives-first-freedom-of-tower-hamlets-of-the-21st-century-1-5533799

- https://www.steppingforwardlondon.org/civic-honours-granted-by-the-london-boroughs.html

Sources

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

Sources

- Cornwell, Jocelyn (1984). Hard-Earned Lives: Accounts of Health and Illness from East London, Tavistock Publications.

- Dancygier, Rafaela M. (2010). Immigration and Conflict in Europe, Cambridge University Press.

- Hill, Dave. "Tower Hamlets: politics, poverty and faith", The Guardian, 19 September 2010. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to London Borough of Tower Hamlets. |

- Tower Hamlets Council

- LBTH find your councillor

- LBTH Ward data report (2005) Information on Tower Hamlets at the ward level