Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the United Kingdom's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity (which receives no government funding).[2] It can seat 5,272.[1]

| Royal Albert Hall | |

|---|---|

Royal Albert Hall from Kensington Gardens | |

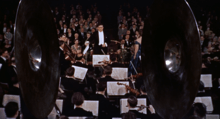

Interior viewed from the Grand Tier | |

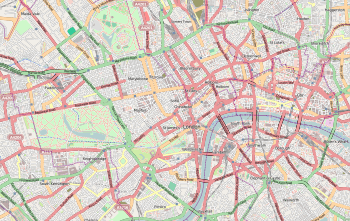

Location within Central London | |

| General information | |

| Type | Concert hall |

| Architectural style | Italianate |

| Address | Kensington Gore London, SW7 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°30′03.7″N 00°10′38.6″W |

| Construction started | 18671 |

| Completed | 18711 |

| Inaugurated | 29 March 1871 |

| Renovated | 1996–2004 |

| Cost | £200,0001 |

| Client | Provisional Committee for the Central Hall of Arts and Sciences |

| Owner | The Corporation of the Hall of Arts and Sciences |

| Height | 135 feet (41 m) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Captain Francis Fowke and Major-General Henry Y. D. Scott |

| Architecture firm | Royal Engineers |

| Main contractor | Lucas Brothers |

| Other information | |

| Seating capacity | 5,272[1] |

| Website | |

| royalalberthall.com | |

| References | |

| 1 – Victorian London: Royal Albert Hall 2 – Royal Albert Hall, London | |

Since the hall's opening by Queen Victoria in 1871, the world's leading artists from many performance genres have appeared on its stage. It is the venue for the Proms concerts, which have been held there every summer since 1941. It is host to more than 390 shows in the main auditorium annually, including classical, rock and pop concerts, ballet, opera, film screenings with live orchestral accompaniment, sports, awards ceremonies, school and community events, and charity performances and banquets. A further 400 events are held each year in the non-auditorium spaces.

The hall was originally supposed to have been called the Central Hall of Arts and Sciences, but the name was changed to the Royal Albert Hall of Arts and Sciences by Queen Victoria upon laying the Hall's foundation stone in 1867, in memory of her husband, Prince Albert, who had died six years earlier. It forms the practical part of a memorial to the Prince Consort; the decorative part is the Albert Memorial directly to the north in Kensington Gardens, now separated from the Hall by Kensington Gore.

History

1800s

In 1851 the Great Exhibition, organised by Prince Albert, the Prince Consort, was held in Hyde Park, London. The Exhibition was a success and led Prince Albert to propose the creation of a permanent series of facilities for the benefit of the public, which came to be known as Albertopolis. The Exhibition's Royal Commission bought Gore House and its scheme was slow, and in 1861 Prince Albert died, without having seen his ideas come to fruition. However, a memorial was proposed for Hyde Park, with a Great Hall opposite.

The proposal was approved, and the site was purchased with some of the profits from the Exhibition. The Hall was designed by civil engineers Captain Francis Fowke and Major-General Henry Y. D. Scott of the Royal Engineers and built by Lucas Brothers.[3] The designers were heavily influenced by ancient amphitheatres but had also been exposed to the ideas of Gottfried Semper while he was working at the South Kensington Museum. The recently opened Cirque d'Hiver in Paris was seen in the contemporary press as the design to outdo. The Hall was constructed mainly of Fareham Red brick, with terra cotta block decoration made by Gibbs and Canning Limited of Tamworth.

The dome (designed by Rowland Mason Ordish) was made of wrought iron and glazed. There was a trial assembly made of the dome's iron framework in Manchester; then it was taken apart again and transported to London by horse and cart. When the time came for the supporting structure to be removed from the dome after reassembly in situ, only volunteers remained on-site in case the structure collapsed. It did drop – but only by five-sixteenths of an inch.[4] The Hall was scheduled to be completed by Christmas Day 1870, and the Queen visited a few weeks beforehand to inspect.[5]

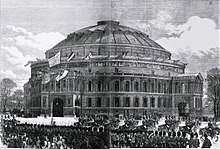

The official opening ceremony of the Hall was on 29 March 1871. A welcoming speech was given by Edward, the Prince of Wales because Queen Victoria was too overcome to speak; "her only recorded comment on the Hall was that it reminded her of the British constitution".[6]

In the concert that followed, the Hall's acoustic problems became immediately apparent. Engineers first attempted to solve the strong echo by suspending a canvas awning below the dome. This helped and also sheltered concert-goers from the sun, but the problem was not solved: it used to be jokingly said the Hall was "the only place where a British composer could be sure of hearing his work twice".

In July 1871, French organist Camille Saint-Saëns performed Church Scene from Faust by Charles Gounod; The Orchestra described his performance as "an exceptional and distinguished performer ... the effect was most marvellous."

Initially lit by gas, the Hall contained a special system where its thousands of gas jets were lit within ten seconds. Though it was demonstrated as early as 1873 in the Hall,[7] full electric lighting was not installed until 1888.[6] During an early trial when a partial installation was made, one disgruntled patron wrote to The Times, declaring it to be "a very ghastly and unpleasant innovation".

In May 1877, Richard Wagner himself conducted the first half of each of the eight concerts which made up the Grand Wagner Festival. After his turn with the baton, he handed it over to conductor Hans Richter and sat in a large armchair on the corner of the stage for the rest of each concert. Wagner's wife Cosima, the daughter of Hungarian virtuoso pianist and composer Franz Liszt, was among the audience.

The Wine Society was founded at the Hall on 4 August 1874,[8] after large quantities of cask wine were found in the cellars. A series of lunches were held to publicise the wines, and General Henry Scott proposed a co-operative company to buy and sell wines.[9]

1900s

In 1906 Elsie Fogerty founded the Central School of Speech and Drama at the Hall, using its West Theatre, now the Elgar Room as the School's theatre. The School moved to Swiss Cottage in north London in 1957. Whilst the School was based at the Royal Albert Hall students who graduated from its classes included Judi Dench, Vanessa Redgrave, Lynn Redgrave, Harold Pinter, Laurence Olivier and Peggy Ashcroft.[10]

In 1911 Russian pianist and composer Sergei Rachmaninoff performed as a part of the London Ballad Concert. The recital included his 'Prelude in C-sharp minor' and 'Elegie in E-flat minor' (both from Morceaux de Fantaisie).[11]

In 1933 German physicist Albert Einstein led the 'Einstein Meeting' at the hall for the Council for Assisting Refugee Academics, a British charity.[12]

In 1936, the Hall was the scene of a giant rally celebrating the British Empire on the occasion of the centenary of Joseph Chamberlain's birth. In October 1942, the Hall suffered minor damage during World War II bombing, but in general, was left mostly untouched as German pilots used the distinctive structure as a landmark.[7]

In 1949 the canvas awning was removed and replaced with fluted aluminium panels below the glass roof, in a new attempt to solve the echo; but the acoustics were not properly tackled until 1969 when large fibreglass acoustic diffusing discs (commonly referred to as "mushrooms" or "flying saucers") were installed below the ceiling.[6] In 1968, the Hall hosted the Eurovision Song Contest 1968[13] and in 1969–1989, the Miss World contest was staged in the venue.[14]

From 1996 until 2004, the Hall underwent a programme of renovation and development supported by a £20 million grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund and £20m from Arts Council England to enable it to meet the demands of the next century of events and performances. Thirty "discreet projects" were designed and supervised by the architecture and engineering firm BDP without disrupting events. These projects included improved ventilation to the auditorium, more bars and restaurants, improved seating, better technical facilities and improved backstage areas. Internally, the Circle seating was rebuilt during June 1996 to provide more legroom, better access and improved sightlines.[15]

2000s

The largest project of the ongoing renovation and development was the building of a new south porch – door 12, accommodating a first-floor restaurant, new ground floor box office and below ground loading bay. Although the exterior of the building was largely unchanged, the south steps leading down to Prince Consort Road were demolished to allow construction of underground vehicle access and loading bay with accommodation for three HGVs carrying all the equipment brought by shows. The steps were then reconstructed around a new south porch, named The Meitar Foyer after a significant donation from Mr & Mrs Meitar. The porch was built on a similar scale and style to the three pre-existing porches at Door 3, 6 and 9: these works were undertaken by Taylor Woodrow Construction.[15] The original steps featured in the early scenes of 1965 film The Ipcress File. On 4 June 2004, the project received the Europa Nostra Award for remarkable achievement.[16] The East (Door 3) and West (Door 9) porches were glazed and new bars opened along with ramps to improve disabled access. The Stalls were rebuilt in a four-week period in 2000 using steel supports allowing more space underneath for two new bars; 1,534 unique pivoting seats were laid – with an addition of 180 prime seats. The Choirs were rebuilt at the same time. The whole building was redecorated in a style that reinforces its Victorian identity. 43,000 sq ft (4,000 m2) of new carpets were laid in the rooms, stairs and corridors – specially woven with a border that follows the oval curve of the building.[17]

Between 2002 and 2004, there was a major rebuilding of the great organ (known as the Voice of Jupiter),[18] built by "Father" Henry Willis in 1871 and rebuilt by Harrison & Harrison in 1924 and 1933. The rebuilding was performed by Mander Organs,[19] and it is now the second-largest pipe organ in the British Isles with 9,997 pipes in 147 stops. The largest is the Grand Organ in Liverpool Cathedral which has 10,268 pipes.[20]

2010s

2011

During the first half of 2011, changes were made to the backstage areas to relocate and increase the size of crew catering areas under the South Steps away from the stage and create additional dressing rooms nearer to the stage.[21]

2012

During the summer of 2012, the staff canteen and some changing areas were expanded and refurbished by contractor 8Build.[22]

2013

From January to May the Box Office area at Door 12 underwent further modernisation to include a new Café Bar on the ground floor, a new Box Office with shop counters and additional toilets. The design and construction were carried out by contractor 8Build. Upon opening it was renamed 'The Zvi and Ofra Meitar Porch and Foyer.' owing to a large donation from the couple.[23]

In Autumn 2013, work began on replacing the Victorian steam heating system over three years and improving and cooling across the building. This work followed the summer Proms season during which temperatures were unusually high.[24]

2014

From January the Cafe Consort on the Grand Tier was closed permanently in preparation for a new restaurant at the cost of £1 million. The refurbishment, the first in around ten years, was designed by consultancy firm Keane Brands and carried out by contractor 8Build.[25] Verdi – Italian Kitchen was officially opened on 15 April with a lunch or dinner menu of 'stone baked pizzas, pasta and classic desserts'.[26][27]

Design

The Hall, a Grade I listed building,[28] is an ellipse in plan, with its external major and minor axis of 272 and 236 feet (83 and 72 meters), and its internal minor and major axis of 185 and 219 feet (56 and 67 m).[29][30] The great glass and wrought-iron dome roofing the Hall is 135 ft (41 m) high. The Hall was originally designed with a capacity for 8,000 people and has accommodated as many as 12,000 (although present-day safety restrictions mean the maximum permitted capacity is now 5,272[1] including standing in the Gallery).

Around the outside of the building is 800–foot–long terracotta mosaic frieze, depicting "The Triumph of Arts and Sciences", in reference to the Hall's dedication.[29] Proceeding anti-clockwise from the north side the sixteen subjects of the frieze are:

- Various Countries of the World bringing in their Offerings to the Exhibition of 1851

- Music

- Sculpture

- Painting

- Princes, Art Patrons and Artists

- Workers in Stone

- Workers in Wood and Brick

- Architecture

- The Infancy of the Arts and Sciences

- Agriculture

- Horticulture and Land Surveying

- Astronomy and Navigation

- A Group of Philosophers, Sages and Students

- Engineering

- The Mechanical Powers

- Pottery and Glassmaking

Above the frieze is an inscription in 12-inch-high (30 cm) terracotta letters that combine historical fact and Biblical quotations:

This hall was erected for the advancement of the arts and sciences and works of industry of all nations in fulfilment of the intention of Albert Prince Consort. The site was purchased with the proceeds of the Great Exhibition of the year MDCCCLI. The first stone of the Hall was laid by Her Majesty Queen Victoria on the twentieth day of May MDCCCLXVII and it was opened by Her Majesty the Twenty Ninth of March in the year MDCCCLXXI. Thine O Lord is the greatness and the power and the glory and the victory and the majesty. For all that is in the heaven and in the earth is Thine. The wise and their works are in the hand of God. Glory be to God on high and on earth peace.

Below the Arena floor there is room for two 4000 gallon water tanks, which are used for shows that flood the arena like Madame Butterfly.[31]

Amphi corridor on the ground floor, facing West from Door 6

Amphi corridor on the ground floor, facing West from Door 6 The Door 9 porch at night

The Door 9 porch at night Second Tier corridor, facing West from Door 6

Second Tier corridor, facing West from Door 6- Fluted aluminium roof and diffuser discs seen from the Gallery

- The glazed roof and vertical struts supporting the fluted aluminium ceiling, beneath the wooden floor

Events

The Hall has been affectionately titled "The Nation's Village Hall".[32] The first concert was Arthur Sullivan's cantata On Shore and Sea, performed on 1 May 1871.[33][34]

Many events are promoted by the Hall, whilst since the early 1970s promoter Raymond Gubbay has brought a range of events to the Hall including opera, ballet and classical music. Some events include classical and rock concerts, conferences, banquets, ballroom dancing, poetry recitals, educational talks, motor shows, ballet, opera, film screenings and circus shows. It has hosted many sporting events, including boxing, squash, table tennis, basketball, wrestling including the first Sumo wrestling tournament to be held in London as well as UFC 38 (the first UFC event to be held in the UK), tennis and even a marathon.[35][36] The hall first hosted boxing in 1918, when it hosted a tournament between British and American servicemen. There was a colour bar in place at the Hall, preventing black boxers from fighting there, between 1923 and 1932.[37] Greats of British boxing such as Frank Bruno, Prince Naseem Hamed, Henry Cooper and Lennox Lewis have all appeared at the venue. The hall's storied boxing history was halted in 1999 when a court ordered that boxing and wrestling matches could no longer be held at the venue. In 2011 that decision was overturned. In 2019 Nicola Adams won the WBO Flyweight title which was the first fight for a world title at the venue since Marco Antonio Barrera took on Paul Lloyd in 1999.[38]

On 6 April 1968, the Hall hosted the Eurovision Song Contest which was broadcast in colour for the first time.[39] The first Miss World contest broadcast in colour was also staged at the venue in 1969 and remained at the Hall every year until 1989.

One notable event was a Pink Floyd concert held 26 June 1969, the night they were banned from ever playing at the Hall again after shooting cannons, nailing things to the stage, and having a man in a gorilla suit roam the audience. At one point Rick Wright went to the pipe organ and began to play "The End of the Beginning", the final part of "Saucerful of Secrets", joined by the brass section of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (led by the conductor, Norman Smith) and the ladies of the Ealing Central Amateur Choir.[40] A portion of the pipe organ recording is included on Pink Floyd's album The Endless River.[41]

On 18 June 1985, British gothic rock band The Sisters of Mercy recorded their live video album Wake at the Hall. Between 1996 and 2008, the Hall hosted the annual National Television Awards all of which were hosted by Sir Trevor McDonald.[42]

Benefit concerts include the 1997 Music for Montserrat concert, arranged and produced by George Martin, an event which featured artists such as Phil Collins, Mark Knopfler, Sting, Elton John, Eric Clapton and Paul McCartney,[43] and 2012 Sunflower Jam charity concert with Queen guitarist Brian May performing alongside bassist John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin, drummer Ian Paice of Deep Purple, and vocalists Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden and Alice Cooper.[44]

In 2006, Pink Floyd guitarist, David Gilmour performed at the Hall for the first time since Pink Floyd's 1969 ban. He performed at the Hall as part of his On an Island Tour. The shows were filmed and used for the live video release, Remember That Night (2007). Rock band The Killers recorded their first live album, Live from the Royal Albert Hall in July 2009.

On 5 April 2010, Swedish progressive metal band Opeth recorded In Live Concert at the Royal Albert Hall, as they became the first Death metal band to ever perform at the Hall. The concert was part of the band's Evolution XX: An Opeth Anthology tour, made in celebration of their 20th anniversary.

On 2 October 2011, the Hall staged the 25th-anniversary performance of Andrew Lloyd Webber's The Phantom of the Opera, which was broadcast live to cinemas across the world and filmed for DVD.[45] Lloyd Webber, the original London cast including Sarah Brightman and Michael Crawford, and four previous actors of the titular character, among others, were in attendance – Brightman and the previous Phantoms (aside from Crawford) performed an encore.

On 24 September 2012, Classic FM celebrated the 20th anniversary of their launch with a concert at the Hall. The program featured live performances of works by Handel, Puccini, Rachmaninoff, Parry, Vaughan Williams, Tchaikovsky and Karl Jenkins who conducted his piece The Benedictus from The Armed Man in person.[46]

On 19 November 2012, the Hall hosted the 100th-anniversary performance of the Royal Variety Performance, attended by the HM Queen Elizabeth II and HRH Duke of Edinburgh, with boy-band One Direction among the performers.[47]

During his Rattle That Lock Tour, David Gilmour performed at the Royal Albert Hall eleven times between September 2015 and September 2016, once in aid of Teenage Cancer Trust.

On 13 November 2015, Canadian musician Devin Townsend recorded his second live album Ziltoid Live at the Royal Albert Hall.

_(cropped).jpg)

Kylie Minogue performed at the Royal Albert Hall on 11 December 2015 and 9–10 December 2016 as part of her "A Kylie Christmas" concert series. A live video release of the 11 December 2015 date was released via iTunes and Apple Music on 25 November 2016.

On 3 May 2016, singer-songwriter and Soundgarden vocalist Chris Cornell played at the hall what would become the last UK show of his life as part of his "Higher Truth" European tour. Cornell performed stripped-back acoustic renditions from his back-catalogue to rave reviews, including songs from the likes of Soundgarden, Temple of the Dog, Audioslave and his solo work. Cornell died on 18 May 2017.[48]

On 22 April 2016, British rock band Bring Me the Horizon performed and recorded their Live at the Royal Albert Hall album, with accompaniment from the Parallax Orchestra conducted by Simon Dobson. The Album later released on 2 December 2016 through crowdfunding platform PledgeMusic where all proceeds would be donated to Teenage Cancer Trust.

At a press conference held at the Hall in October 2016, Phil Collins announced his return to live performing with his Not Dead Yet Tour, which began in June 2017.[49] The tour included five nights at the Hall which sold out in fifteen seconds.[50] In October 2017, American rock band Alter Bridge also recorded a live album accompanied by the Parallax Orchestra with Simon Dobson. The album and DVD were released in September of the following year. A portion of the proceeds from the sales were donated to the Future Song Foundation.[51]

Also in 2017, the Hall hosted the 70th British Academy Film Awards, often referred to as the BAFTAs, for the first time in 20 years, replacing the Royal Opera House at which the event had been held since 2008.[52]

In 2018, WWE held its second United Kingdom Championship Tournament on 18 and 19 June. In the same year, the world premiere of PlayStation in Concert was organised at the Hall and it featured PlayStation game music from the 1990s up until then. It was arranged by Jim Fowler and performed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.[53]

Comedian Bill Burr filmed his 2019 special Paper Tiger at the Hall.[54]

Regular events

Royal Choral Society

The Royal Choral Society is the longest-running regular performance at the Hall, having given its first performance as the Royal Albert Hall Choral Society on 8 May 1872.[55] From 1876, it established the annual Good Friday performance of Handel's Messiah.[56]

BBC Proms

The BBC Sir Henry Wood Promenade Concerts, known as "The Proms", is a popular annual eight-week summer season of daily classical music concerts and other events at the Hall. In 1942, following the destruction of the Queen's Hall in an air raid, the Hall was chosen as the new venue for the proms.[57] In 1944 with increased danger to the Hall, part of the proms were held in the Bedford Corn Exchange. Following the end of World War II the proms continued in the Hall and have done so annually every summer since. The event was founded in 1895, and now each season consists of over 70 concerts, in addition to a series of events at other venues across the United Kingdom on the last night. In 2009, the total number of concerts reached 100 for the first time. Jiří Bělohlávek described The Proms as "the world's largest and most democratic musical festival" of all such events in the world of classical music festivals.[58]

Proms (short for promenade concerts) is a term which arose from the original practice of the audience promenading, or strolling, in some areas during the concert. Proms concert-goers, particularly those who stand, are sometimes described as "Promenaders", but are most commonly referred to as "Prommers".[59]

Tennis

Tennis was first played at the Hall in March 1970, and the ATP Champions Tour Masters has been played annually every December since 1997.

Classical Spectacular

Classical Spectacular, a Raymond Gubbay production, has been coming to the Hall since 1988. It combines popular classical music, lights and special effects.

Cirque du Soleil

Cirque du Soleil has performed annually, with a show being staged every January since 2003. Cirque has had to adapt many of their touring shows to perform at the venue, modifying the set, usually built for arenas or big top tents instead. The following shows have played the RAH: Saltimbanco (1996, 1997 and 2003), Alegría (1998, 1999, 2006 and 2007), Dralion (2004 and 2005), Varekai (2008 and 2010), Quidam (2009 and 2014), Totem (2011, 2012 and 2019), Koozå (2013 and 2015), Amaluna (2016 and 2017), and most recently Luzia (2020). Amaluna's visit in 2016 marked Cirque's '20 years of Cirque at the Royal Albert Hall' celebration. Cirque's insect-themed show, OVO 2018.[60]

Classic Brit Awards

Since 2000, the Classic Brit Awards has been hosted annually in May at the Hall. It is organised by the British Phonographic Industry.

Festival of Remembrance

The Royal British Legion Festival of Remembrance is held annually the day before Remembrance Sunday.[61]

Institute of Directors

For 60 years the Institute of Directors' Annual Convention has been synonymous with the Hall, although in 2011 and 2012 it was held at indigO2.

English National Ballet

Since 1998 the English National Ballet has had several specially staged arena summer seasons in partnership with the Hall and Raymond Gubbay. These include Strictly Gershwin, June 2008 and 2011, Swan Lake, June 2002, 2004, 2007, 2010 and 2013, Romeo & Juliet (Deane), June 2001 and 2005 and The Sleeping Beauty, April – June 2000.[62]

Teenage Cancer Trust

.jpg)

Starting in the year 2000 the Teenage Cancer Trust has held annual charity concerts (with the exception of 2001). They started as a one-off event but have expanded over the years to a week or more of evenings events. Roger Daltrey of the Who has been intimately involved with the planning of the events.[63]

Graduation ceremonies

The Hall is used annually by the neighbouring Imperial College London and the Royal College of Art for graduation ceremonies. For several years the University of London and Kingston University also held its graduation ceremonies at the Hall.

Films, premières and live orchestra screenings

The venue has screened several films since the early silent days. It was the only London venue to show William Fox's The Queen of Sheba in the 1920s.

The Hall has hosted many premières, including the UK première of Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen, 101 Dalmatians on 4 December 1996, the European première of Spandau Ballet's Soul Boys of the Western World[64] and three James Bond royal world premières; Die Another Day on 18 November 2002 (attended by Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip), Skyfall on 23 October 2012 (attended by Charles, Prince of Wales and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall)[65] and Spectre on 26 October 2015 (attended by Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge).[66]

The Hall held its first 3D world première of Titanic 3D, on 27 March 2012, with James Cameron and Kate Winslet in attendance.[67]

Since 2009, the Hall has also curated regular seasons of English-language film-and-live-orchestra screenings, including The Lord of the Rings trilogy, Gladiator, Star Trek, Star Trek Into Darkness, Interstellar, The Matrix, West Side Story, Breakfast at Tiffany's, Back to the Future, Jaws, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, and the world première of Titanic Live in Concert. The only non-English-language movie to have been screened at the Hall is Baahubali: The Beginning (an Indian movie in Telugu).

National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain

The National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain, one of the most prestigious prizes in the annual brass band contesting calendar, holds the Final of the Championship section at the Royal Albert Hall each October[68]

Beyond the main stage

The Hall hosts hundreds of events and activities beyond its main auditorium. There are regular free art exhibitions in the ground floor Amphi corridor, which can be viewed when attending events or on dedicated viewing dates. Visitors can take a guided tour of the Hall on most days. The most common is the one-hour Grand Tour which includes most front-of-house areas, the auditorium, the Gallery and the Royal Retiring Room. Other tours include Story of the Proms, Behind the Scenes, Inside Out and School tours. Children's events include Storytelling and Music Sessions for ages four and under. These take place in the Door 9 Porch and Albert's Band sessions in the Elgar Room during school holidays. "Live Music in Verdi" takes place in the Italian restaurant on a Friday night featuring different artists each week. "Late Night Jazz" events in the Elgar Room, generally on a Thursday night, feature cabaret-style seating and a relaxed atmosphere with drinks available. "Classical Coffee Mornings" are held on Sundays in the Elgar Room with musicians from the Royal College of Music accompanied with drinks and pastries. Sunday brunch events take place in Verdi Italian restaurant and feature different genres of music.[69]

Regular performers

.jpg)

Eric Clapton is a regular performer at the Hall. Since 1964, Clapton has performed at the Hall over 200 times, and has stated that performing at the venue is like "playing in my front room".[70][71][72] In December 1964, Clapton made his first appearance at the Hall with the Yardbirds. It was also the venue for his band Cream's farewell concerts in 1968 and reunion shows in 2005. He also instigated the Concert for George, which was held at the Hall on 29 November 2002 to pay tribute to Clapton's lifelong friend, former Beatle George Harrison. Clapton passed 200 shows at the Hall in 2015.[72]

David Gilmour played at the Hall in support of two solo albums, while also releasing a live concert on September 2006 entitled Remember That Night which was recorded during his three nights playing at the Hall for his 2006 On an Island tour. Notable guests were Robert Wyatt and David Bowie (who sang lead for "Arnold Layne" and "Comfortably Numb"). The live concert was televised by BBC One on 9 September 2007 and again on 25 May. Gilmour returned to the Hall for four nights in September 2016 (where he was joined in stage by Benedict Cumberbatch for "Comfortably Numb"), having previously played five nights in 2015, to end his 34-day Rattle That Lock Tour.[73] He also made an appearance on 24 April 2016 as part of the Teenage Cancer Trust event.

Shirley Bassey is one of the Hall's most prolific female headline performers having appeared many times at the Hall since the 1970s. In 2001, she sang "Happy Birthday" for the Duke of Edinburgh's 80th birthday concert. In 2007, she sang at Fashion Rocks in aid of the Prince's Trust. On 30 March 2011, she sang at a gala celebrating the 80th birthday of Mikhail Gorbachev.[74] In May 2011, she performed at the Classic Brit Awards, singing "Goldfinger" in tribute to the recently deceased composer John Barry.[75] On 20 June 2011, she returned and sang "Diamonds Are Forever" and "Goldfinger", accompanied by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, as the climax to the memorial concert for Barry.[76]

James Last appeared 90 times at the Hall between 1973 and 2015, making him the most frequent non–British performer to have played the venue.[77]

Education and outreach programme

The hall's education and outreach programme engages with more than 200,000 people a year. It includes workshops for local teenagers led by musicians such as Foals, Jake Bugg, Emeli Sandé, Nicola Benedetti, Alison Balsom and First Aid Kit, innovative science and maths lessons, visits to local residential homes from the venue's in-house group, Albert's Band, under the 'Songbook' banner, and the Friendship Matinee: an orchestral concert for community groups, with £5 admission.

Management

The Hall is managed day to day by the chief executive Craig Hassall and six senior executives. They are accountable to the Council of the Corporation, which is the Trustee body of the charity. The Council is composed of the annually elected president, currently Ian McCulloch, 18 elected Members (either corporate or individual seat owners) and five Appointed Members, one each from Imperial College London, Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, Department for Culture, Media and Sport, British Museum of Natural History and the Royal College of Music.[78]

Awards

The Hall has won several awards across different categories.

- From 1994 to 1998 and in 2003, the Hall won 'International Venue of the Year' in the Pollstar Awards.

- In 2004 and 2005, the Hall won 'International Small Venue of the Year' in the Pollstar Awards.

- In 2006 to 2010, the Hall won 'International Theatre of the Year' in the Pollstar Awards.[79]

- The Hall has won International Live Music Conference Award for 'First Venue to Come into Your Head' in 1998, 2009 and 2013.[80]

- From 2008 to 2012, the Hall was voted Superbrands leading Leisure and Entertainment Destination.[81]

- On 17 October 2012, the Hall won 'London Live Music Venue of the Year' at the third annual London Lifestyle Awards.[82]

- The Hall won the Showcase Award for Teenage Cancer Trust and Event Space of the Year (non-Exhibition), both at the Event Awards 2010.[83]

- The Hall has been voted a CoolBrand from 2009 to 2013 in the 'Attractions & The Arts – general' category.[84]

- In 2010 and 2011, the Hall won 'Best Venue Teamwork Award' at the Live UK Summit.[85]

- The 'Life at the Hall blog won 'Best Venue Blog' at the Prestigious Star Awards in 2012[86] and the Prestigious Star Award Landmark in 2013.[87]

Mislabellings

A famous and widely bootlegged concert by Bob Dylan at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 17 May 1966 was mistakenly labelled the "Royal Albert Hall Concert". In 1998, Columbia Records released an official recording, The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert, that maintains the erroneous title but does include details of the actual location. Recordings from the Royal Albert Hall concerts on 26–27 May 1966 were finally released by the artist in 2016 as The Real Royal Albert Hall 1966 Concert.

Another concert mislabelled as being at the Hall was by Creedence Clearwater Revival. An album by them titled The Royal Albert Hall Concert was released in 1980. When Fantasy Records discovered the show on the album actually took place at the Oakland Coliseum, it retitled the album The Concert.

Pop culture references

A large mural by Peter Blake, titled Appearing at the Royal Albert Hall, is displayed in the Hall's Café Bar. Unveiled in April 2014, it shows more than 400 famous figures who have appeared on the stage.[88]

In 1955, English film director Alfred Hitchcock filmed the climax of The Man Who Knew Too Much at the Hall.[89] The 15-minute sequence featured James Stewart, Doris Day and composer Bernard Herrmann, and was filmed partly in the Queen's Box. Hitchcock was a long-time patron of the Hall and had already set the finale of his 1927 film, The Ring at the venue, as well as his initial version of The Man Who Knew Too Much, starring Leslie Banks, Edna Best and Peter Lorre.[90]

Other notable films shot at the Hall include Major Barbara, Love Story, The Seventh Veil, The Ipcress File, A Touch of Class, Shine and Spice World.

In the song "A Day in the Life" by the Beatles, the Albert Hall is mentioned. The verse goes as follows:

I read the news today, oh boy

four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire

and though the holes were rather small

they had to count them all

now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall

I'd love to turn you on.

The song "Session Man" by The Kinks references the Hall:

He never will forget at all

The day he played at Albert Hall.

In the song "Shame" by Robbie Williams and Gary Barlow, Barlow mentions the Hall in his verse:

I read your mind and tried to call, my tears could fill the Albert Hall.

In some variants of "Hitler Has Only Got One Ball", Hitler's second testicle is mentioned as being in the Hall.

Transport links

| London Buses |

Royal Albert Hall 9, 23, 52, 360, 452 |

| London Underground |

Gloucester Road |

| High Street Kensington | |

| Knightsbridge | |

| South Kensington |

See also

- Albertopolis

- The Great Exhibition

- Exhibition Road

- Prince Albert

- List of concert halls

- List of tallest domes

References

- Colson, Thomas. "A 12-seat Grand Tier box at the Royal Albert Hall is on sale for £2.5 million". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Hope, Jasper (18 June 2013). "It's Hall to do with the experience". Metro.

- "Charles Lucas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Engineering Timelines: Royal Albert Hall

- Michael Forsyth (1985). "Buildings for Music: The Architect, the Musician, and the Listener from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Day" p. 158.

- "The Building" (PDF). Royal Albert Hall. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Timeline". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Edmund Penning-Rowsell, A Short History of The Wine Society, 1989.

- "History of the Society". The Wine Society. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Lolly, Susi (2006). The central book. London: Oberon Books. ISBN 9781840027105. OCLC 85776670.

- "Keynotes". The Sketch. Vol. 76. 8 November 1911. p. 142. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Keyte, Suzanne (9 October 2013). "3 October 1933 – Albert Einstein presents his final speech given in Europe, at the Royal Albert Hall". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Eurovision Song Contest 1968". EBU. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- van der Pas, Natasha (26 November 2014). "From the Archives: Twenty years of Miss World at the Royal Albert Hall". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Projects: Royal Albert Hall". BDP.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Europa Nostra award for Royal Albert Hall" (Press release). BDP.com. 4 June 2004. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011.

- "The Royal Albert Hall". linneycooper.co.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Mighty Voice of Jupiter pipes up at Royal Albert Hall". South China Morning Post. 4 July 2004. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- "The Grand Organ, Royal Albert Hall". Mander Organs. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Facts and figures". Liverpool Cathedral. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- "Planning Application Documents". Westminster City Council. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "8build on site at the Royal Albert Hall". 8Build. July 2012. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "8build – The Royal Albert Hall". 8Build. January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Clark, Nick. "Sweaty business: Royal Albert Hall seeks solution to sweltering temperatures at Proms". Independent. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Keane Brands designs interiors for Royal Albert Hall's Verdi restaurant". 23 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Verdi – Italian Kitchen". Royal Albert Hall. April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Verdi – Italian Kitchen: building work update". Life at the Hall. 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Royal Albert Hall". CharitiesDirect.com. December 2009. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Gibbs, Fiona (January 2018). The Royal Albert Hall: A Case Study of an Evolving Cultural Venue (PDF) (PhD). Royal College of Music.

- The British Foreign Mechanic and Scientific Instructor. J. Sydal. 23 July 1870. p. 30.

- "3 places to look out for at the Behind the Scenes Day at the Royal Albert Hall". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Tremayne Carew Pole, Managing Director (2006). A Hedonist's Guide to London. London: Filmer.ltd. ISBN 1-905428-03-0. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Discography of Sir Arthur Sullivan: On Shore and Sea (1871)". 24 December 2003. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Meirion Hughes and Robert Stradling (2001). The English Musical Renaissance 1840–1940. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5830-9. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Compiled and Edited by Hugh Cortazzi (2001). Japan Experiences: Fifty Years, One Hundred Views. Japan Library. pp. 250–251. ISBN 1-903350-04-2. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Sheila Tully Boyle and Andrew Bunie (30 September 2005). Paul Robeson: The Years of Promise and Achievement. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 210–212. ISBN 1-55849-505-3. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Worries of Jeff Dickson: Albert Hall to Abolish Colour Bar?". Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette. 6 January 1932. Retrieved 22 September 2019 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/boxing/46892142

- "Eurovision Song Contest 1968". EBU. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- "Pink Floyd – The Final Lunacy, Royal Albert Hall, London 26th June 1969". Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "For their last-ever album The Endless River, Pink Floyd recorded on a boat". Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "1996–2008 National Television Awards (NTAS)". royalalberthall.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Billboard 6 September 1997". p.59. Billboard. Retrieved 7 January 2012

- "Led Zeppelin, Iron Maiden and Queen band members perform at charity rock show". NME. Retrieved 7 January 2013

- Whitman, Howard. "Blu-ray Review: Phantom of the Opera at the Royal Albert Hall". Technologytell. technologytell.com. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- "Classic FM Live: the programme".

- "Royal Variety Performance marks 100th anniversary". BBC News. Retrieved 7 January 2013

- "Pictures and setlist: Chris Cornell's Higher Truth at the Royal Albert Hall". royalalberthall.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Phil Collins marks comeback with European tour". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "Phil Collins to play his biggest-ever solo show in Hyde Park". The Guardian. 3 November 2016.

- https://loudwire.com/alter-bridge-parallax-orchestra-live-at-the-royal-albert-hall/

- "In pictures: Film's biggest stars celebrated at the 70th EE BAFTAs ceremony". royalalberthall.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "PlayStation at the Royal Albert Hall: Chips with Everything podcast". The Guardian. June 2018.

- https://www.monstersandcritics.com/smallscreen/where-was-bill-burr-paper-tiger-filmed/

- "OUR PERFORMANCE HISTORY & ARCHIVE". royalalberthall.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Royal Choral Society and the Royal Albert Hall: sharing histories since 1871". royalalberthall.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Christopher Fifield (2005). Ibbs and Tillett: The Rise and Fall of a Musical Empire. Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 241–242. ISBN 1-84014-290-1. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Jiří Bělohlávek, Speech from The Last Night of the Proms 2007, 8 September 2007.

- Liz Bondi; et al. (2002). Subjectivities, Knowledges, and Feminist Geographies. Lahham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-7425-1562-1. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "OVO: Take a look backstage at Cirque du Soleil's OVO, with Kyle the dragonfly!". royalalberthall.com. royalalberthall.com. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- Nigel R. Jones (2005). Architecture of England, Scotland and Wales. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 220–223. ISBN 0-313-31850-6. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- "Other repertoire". English National Ballet. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- "What we do-Royal Albert Hall". Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "Spandau Ballet Film to receive its European Premiere at the Royal Albert Hall" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Life at the Hall. Retrieved 5 October 2014

- "Skyfall premiere is biggest and best – Daniel Craig". BBC News. 24 October 2012.

- "Stars join royals for Spectre premiere". BBC News. 26 October 2015.

- "Titanic: Kate Winslet and James Cameron at 3D premiere". BBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2012

- "Introduction | National Brass Band Championships of Great Britain". www.nationalbrassbandchampionships.com. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "What's on and Buy Tickets". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Eric Clapton Starts Royal Albert Hall Run With Classics and Covers". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 7 January 2013

- "Eric Clapton celebrates 50 years as a professional musician" Archived 10 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Life at the Hall. Retrieved 7 January 2013

- "Exclusive pictures: Eric Clapton hits 200 Royal Albert Hall shows" (24 May 2015). Royal Albert Hall.com. 9 January 2018.

- "Benedict Cumberbatch joins David Gilmour on stage to sing Comfortably Numb". The Telegraph. 10 July 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Thompson, Warwick (31 March 2011). "Sharon Stone, Schwarzenegger Salute Gorbachev at Gala Marathon". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- McWatt, Julia. "Dame Shirley and Katherine Jenkins steal the show at Classic Brits". Wales Online. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- "Composer John Barry remembered at memorial concert". BBC. 21 June 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "James Last to say farewell at Royal Albert Hall". Music-news. 12 February 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "About the Hall – Trustees". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Pollstar Awards Archive". Pollstarpro. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Arthurs Hall of Fame". ilmc.com. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Royal Albert Hall voted Superbrands leading Leisure and Entertainment Destination". Superbrands. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "London Live Music Venue of the Year". London life style awards. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Event Awards 2010: the winners". Event Magazine. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Official Results" (PDF). Coolbrands.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Royal Albert Hall celebrates Best Venue Teamwork Award win at the Live UK Summit". Royal Albert Hall. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Prestigious Star Awards 2012" (PDF). Prestigious Venues. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Prestigious Star Awards 2013" (PDF). Prestigious Venues. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Sir Peter Blake mural masterpiece unveiled at the Hall – Royal Albert Hall". Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Royal S. Brown (1994). "Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music". p. 75, 1994

- "The Film Programme". BBC.

17 September 2015

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Albert Hall. |

- Official site with timeline

- Read a detailed historical record about the Hall

- Architecture of the Hall from the Royal Institute of British Architects

- Royal Albert Hall at Structurae

- Royal Albert Hall Survey of London entry

- Albert Hall (Victorian London)

| Preceded by Großer Festsaal der Wiener Hofburg Vienna |

Eurovision Song Contest Venue 1968 |

Succeeded by Teatro Real Madrid |