Shenzhen

Shenzhen (/ˈʃɛnˈdʒɛn/; Chinese: 深圳; Mandarin pronunciation: [ʂə́n.ʈʂə̂n] (![]()

Shenzhen 深圳市 | |

|---|---|

Prefecture-level and Sub-provincial city | |

From top, left to right: Aerial view of Futian, Shennan Road, Window of the World, Luohu district, China Resources Headquarters in Nanshan, Ping An Finance Centre | |

| |

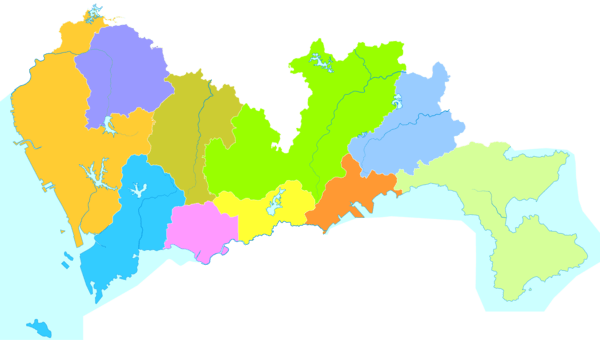

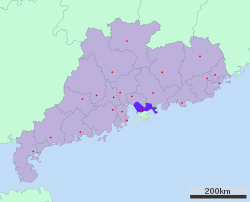

Location of Shenzhen City jurisdiction in Guangdong | |

Shenzhen Location of the city center in Guangdong  Shenzhen Shenzhen (China)  Shenzhen Shenzhen (Asia) | |

| Coordinates (Civic Square (市民广场)): 22°32′29″N 114°03′35″E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Guangdong |

| County-level divisions | 9 |

| Settled | 331 |

| Village | 1953 |

| City | 23 January 1979 |

| SEZ formed | 1 May 1980 |

| Municipal seat | Futian District |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • CPC Committee Secretary | Wang Weizhong |

| • Mayor | Chen Rugui |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level and Sub-provincial city | 2,050 km2 (790 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,748 km2 (675 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–943.7 m (0–3,145.7 ft) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Prefecture-level and Sub-provincial city | 12,528,300 |

| • Density | 6,100/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018)[2] | 12,905,000 |

| • Urban density | 7,400/km2 (19,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 23,300,000 |

| • Major ethnicities | Han |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 518000 |

| Area code(s) | 755 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-GD-03 |

| GRP (Nominal) | 2019[4] |

| - Total | ~¥2.6 trillion ($0.39T) |

| - Per capita | ~¥200,000 ($30230) |

| - Growth | |

| Licence plate prefixes | 粤B |

| City flower | Bougainvillea |

| City trees | Lychee and Mangrove[5] |

| Website | sz.gov.cn |

| Shenzhen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Shenzhen" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 深圳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | Sāmjan or Sàmjan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Sam1 zan3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Deep Drainage" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shenzhen's cityscape results from its vibrant economy—made possible by rapid foreign investment following the institution of the policy of "reform and opening-up" in 1979.[6] The city is a leading global technology hub, dubbed by media China's Silicon Valley.[7][8][9][10][11] It was one of the fastest-growing cities in the world in the 1990s and the 2000s,[12] and has been ranked second on the list "top 10 cities to visit in 2019" by Lonely Planet.[13]

Shenzhen, which roughly follows the administrative boundaries of Bao'an County, officially became a city in 1979, taking its name from the former county town, whose train station was the last stop on the Mainland Chinese section of the railway between Canton and Kowloon.[14] In 1980, Shenzhen was established as China's first special economic zone.[15] Shenzhen's registered population as of 2017 was estimated at 12,905,000,[1] but local police and authorities estimate the population at about 20 million, due to large populations of short-term residents,[lower-alpha 1] unregistered floating migrants, part-time residents, commuters, visitors, as well as other temporary residents.[16][17]

Shenzhen hosts the Shenzhen Stock Exchange as well as the headquarters of numerous multinational companies such as JXD, Vanke, Hytera, CIMC, SF Express, Shenzhen Airlines, Nepstar, Hasee, Ping An Bank, Ping An Insurance, China Merchants Bank, Evergrande Group, Tencent, ZTE, OnePlus, Huawei, DJI and BYD.[18] Shenzhen ranks 9th in the 2019 Global Financial Centres Index.[19] It has the third busiest container port in the world.[20]

Toponymy

The earliest known recorded mention of the name zhen could date from 1410, during the Ming Dynasty.[21] Locals call the drains in paddy fields "zhen" (Chinese: 圳; lit.: 'ditch, drain'). Shenzhen was named after a deep (Chinese: 深; lit.: 'deep') drain that was located within the area."[22][23]

History

Prehistory to Ming era

The oldest evidence of humans in the area on which Shenzhen was established dates back during the mid-Neolithic period.[24][25] Since then, this area has seen human activity from more than 6,700 years ago, with Shenzhen's historic counties first established 1,700 years ago, and the historic towns of Nantou and Dapeng, which was built on the area that is now Shenzhen, established more than 600 years ago.[26] The Hakka people also have a history in Shenzhen since 300 years ago when they first immigrated.

In 214 BC, when Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China under the Qin Dynasty, the area went under the jurisdiction of the established Nanhai County, one of three counties that were set up in Lingnan, and was assimilated into Zhongyuan culture.[27] In 331 AD, the Eastern Jin administration split up Nanhai County into two counties: Dongguan County in the north and Bao'an County in the south, with both under the administration of Dongguan Prefecture.[28] In 590, the Sui administration merged Dongguan County and Bao'an County back into Nanhai County, and set the local government in the town of Nantou, though this was reversed by the Tang administration in 757.

During the Song Dynasty, Nantou and the surrounding area became an important trade hub for salt and spices in the South China Sea.[27][29] The area then became known for producing pearls during the Yuan Dynasty. In the early Ming era, Chinese sailors of a fleet would go to a Mazu temple in Chiwan (in present-day Nanshan District) to pray as they go to Nanyang (Southeast Asia). The Battle of Tunmen, when the Ming won a naval battle against invading Portuguese, was fought south of Nantou.[30] In 1573, the Ming administration dissolved Bao'an County to establish Xin'an County, based in Nantou, which had authority over regions that would be Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Xin'an County's economy primarily was based on the production and trade of salt, tea, spices, and rice.

Qing-era to 1940s

To prevent a rebellion from Ming loyalists under Zheng Chenggong, better known as Koxinga, on the Chinese coast, the recently established Qing administration re-organized coastal provinces.[27] As a result, Xin'an County lost two-thirds of its territory to the neighboring Dongguan County and was later incorporated into Dongguan in 1669, though Xin'an was restored about 15 years later, in 1684. As of 1688, there were 28 towns in Xin'an County, of which one of the towns is named Shenzhen.[31] When the Qing lost to the United Kingdom in both Opium Wars in 1842 and 1860, the Kowloon Peninsula and Hong Kong Island were ceded from Xin'an to the British in the Treaty of Nanking and the Convention of Peking. On 21 April 1898, the Qing government signed a "Special Article for the Exhibition of Hong Kong's Borders" with the United Kingdom, and leased the New Territories from Xin'an to the United Kingdom for 99 years. Shenzhen was occupied by the British under Henry Arthur Blake, the then-governor of Hong Kong for half-a-year in 1899.[32] From the 3,076 square kilometres (1,188 sq mi) of territory that Xin'an held before the treaties, 1,055.61 square kilometres (407.57 sq mi) of the county's land was ceded to the British.[28]

In response to the Wuchang Uprising in 1911, Xin'an residents rebelled against the local Qing administration and successfully overthrew them.[33] In the same year the Chinese section of the Kowloon–Canton Railway (KCR) was opened to the public, and the last stop of the Chinese side, named Shenzhen Railway Station at the town of Shenzhen, which had opened recently, helped the town's economy and opened Shenzhen up to the world.[32][34] In 1913, the Republic of China administration renamed Xin'an County back to Bao'an County to prevent confusion from another county of the same name in Henan Province.[27] During the Canton–Hong Kong strike, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions set up a reception station for strike workers in Hong Kong in Shenzhen.[35] Strike workers were also given pickets and armored vehicles by the strike committee to create a blockade around Hong Kong. In 1931, Chen Jitang and his family established several casinos in Shenzhen, the largest of which being Shumchun Casino.[36] While only in operation until 1936, they significantly increased KCR's passenger traffic to and from Shenzhen.

During World War II, the Japanese occupied Shenzhen and Nantou,[27] forcing the Bao'an County government to relocate to the neighboring Dongguan County.[37][38] In 1941, the Japanese army tried to cross into Hong Kong through the Lo Wu Bridge in Shenzhen, though this was detonated by the British, preventing the Japanese from entering Hong Kong.[39] When Japan surrendered on May 1945, the Bao'an County government moved back to Nantou.

1950s to 1970s

In 1953, four years after the founding of the People's Republic of China, the Bao'an County government decided to move to Shenzhen, since the city was closer to the KCR and had a larger economy than Nantou.[27] From the 1950s to the end of the 1970s, Shenzhen and the rest of Bao'an County oversaw a huge influx of refugees trying to escape to Hong Kong from the upheavals that were occurring in mainland China, and a range from 100,000[40] to 560,000[41] refugees resided in the county.

In January 1978, a Central Inspection Team sent by the State Council investigated and established the issue of creating a foreign trade port in Bao'an County.[42] In May, the investigation team wrote the "Hong Kong and Macao Economic Investigation Report" and proposed to turn Bao'an County and Zhuhai into commodity export bases. In August 1978, the Huiyang District Committee reported to the Provincial Committee on the "Report on the Request for the Change of Bao'an County to Shenzhen". On 18 October, the Standing Committee of the Guangdong Provincial Party Committee decided to change Bao'an County into Bao'an City and to turn it into a medium-level prefecture-level city with a foreign trade base. The Huiyang District Committee and the Bao'an County Committee, however, defended the change to rename Bao'an County to Shenzhen, claiming that people in the world know more about Shenzhen and its port than they know about Bao'an County.

On 23 January 1979, the Guangdong provincial administration and the district of Huiyang announced their proposal to rename Bao'an County to Shenzhen and was approved and put into effect by the State Council on March 5 of that year.[42] Also, the city would establish six districts: Luohu, Nantou, Songgang, Longhua, Longgang and Kuiyong. On 31 January 1979, the Central Committee of the Communist Party approved a plan to establish the Shekou Industrial Zone in Shenzhen with the purpose "to lead domestic, overseas, and diversified operations, industrial and commercial integration, and trading" based on the systems of that of Hong Kong and Macau.[43] The Shekou Industrial Zone project was led by Hong Kong-based China Merchants Group under Yuan Geng's leadership and was to become the first export processing industrial zone in mainland China.

At the beginning of April 1979, the Standing Committee of Guangdong Province discussed and proposed to the Central Committee to set up a "trade cooperation zone" in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Shantou.[42] In the same month, the Central Working Conference decided on the "Regulations on Vigorously Developing Foreign Trade to Increase Foreign Exchange Income" and agreed to pilot the first special economic zones (SEZ) in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen.[44] In November, Shenzhen was elevated to the status of prefecture-level city at the regional level by the Guangdong provincial administration.[33]

Special Economic Zone (1980s–present)

In May 1980, the Central Committee designated Shenzhen as an SEZ,[27] which was promoted by then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and created to be an experimental ground for the practice of market capitalism within a community guided by the ideals of "socialism with Chinese characteristics".[45][46][47] On 26 August, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPC) approved the "Regulations of the Guangdong Special Economic Zone."[48] Under these regulations, Shenzhen formulated a series of preferential policies to attract foreign investment, including business autonomy, taxation, land use, foreign exchange management, product sales, and entry and exit management. Through the processing of incoming materials, compensation trade, joint ventures, cooperative operations, sole proprietorship, and leasing, the city has attracted a large amount of foreign investment and helped popularize and enable rapid development of the SEZ concept.

In March 1981, Shenzhen was promoted to a sub-provincial city.[24][27] There were plans for Shenzhen to develop its currency, but the plans were shelved due to the risk and the disagreement that a country should not be operating with two currencies.[49] To enforce law and order in the city, the Shenzhen government erected barbed wire and checkpoints between the land borders of the main sections of the SEZ and the SEZ outskirts, as well as the rest of China, in 1983, which was known as the second line (Chinese: 二线关).[50][51] In November 1988, Shenzhen became a separate city (计划单列市), meaning that the city can implement policies that are different from those in the national plan, and was given the right of provincial-level economic administration.

In December 1990, under the authority of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange was established to provide a platform for centralized securities trading.[52] In February 1992, the Standing Committee of the NPC granted the government of Shenzhen the power to make local laws and regulations.[23] In 1996 and early 1997, the Shenzhen Guesthouse Hotel in Shenzhen was home to the Provisional Legislative Council and Provisional Executive Council of Hong Kong in preparation for the handover of Hong Kong in 1997.[53][54]

By 2001, as a result of Shenzhen's increasing economic prospects, increasing numbers of migrants from mainland China chose to go to Shenzhen and stay there instead of trying to illegally cross into Hong Kong.[55] There were 9,000 captured border-crossers in 2000, while the same figure was 16,000 in 1991. Around the same time, Shenzhen hosted the second Senior Officials' Meeting of APEC China 2001 on 26 May 2001 in its southern manufacturing center and port.[56] In May 2008, the State Council approved the Shenzhen SEZ to promote Shenzhen's administrative management system, economic system, social field, independent innovation system and mechanism, system and mechanism for opening up and regional cooperation, and resource conservation and environmental friendliness.[57]

On 1 July 2010, the State Council dissolved the "second line," and expanded the Shenzhen SEZ to include all districts, a five-fold increase over its pre-expansion size.[58] On 26 August 2010, on the 30th anniversary of the establishment of the Shenzhen SEZ, the State Council approved the "Overall Development Plan for Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone."[59] In August 2011, the city hosted the 26th Universiade, an international multi-sport event organized for university athletes.[60] In April 2015, the Shekou Industrial Zone and the Qianhai Zone were integrated within the newly-established Guangdong Free-Trade Zone.[61]

On 18 August 2019, the central government in Beijing unveiled reform plans covering economical, social, and political sectors of Shenzhen, intending to have the SEZ be a model city for others in China to follow.[62]

Geography

Shenzhen is located within the Pearl River Delta, bordering Hong Kong to the south, Huizhou to the north and northeast, Dongguan to the north and northwest. Lingdingyang and Pearl River to the west and Mirs Bay to the east and roughly 100 kilometres (62 mi) southeast of the provincial capital of Guangzhou. As of the end of 2017, the resident population of Shenzhen was 12,528,300, of which the registered population was 4,472,200, the actual administrative population was over 20 million.[63] It makes up part of the Pearl River Delta built-up area with 44,738,513 inhabitants, spread over 9 municipalities (including Macau). The city is elongated measuring 81.4 kilometers from east to west while the shortest section from north to south is 10.8 kilometers.

Over 160 rivers or channels flow through Shenzhen. There are 24 reservoirs within the city limits with a total capacity of 525 million tonnes.[64] Notable rivers in Shenzhen include the Shenzhen River, Maozhou River and Longgang River.[65]

Shenzhen is surrounded by many islands. Most of them fall under the territory of neighbouring areas such as Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Huiyang District, Huizhou. But there are several islands under Shenzhen's jurisdiction, such as Nei Lingding Island, Dachan Island (Tai Shan Island), Xiaochan Island, Mazhou, Laishizhou, Zhouzai and Zhouzaitou. (See List of islands in Shenzhen)

Climate

| Shenzhen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Although Shenzhen is situated about a degree south of the Tropic of Cancer, due to the Siberian anticyclone it has a warm, monsoon-influenced, humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa). Winters are mild and relatively dry, due in part to the influence of the South China Sea, and frost is very rare; it begins dry but becomes progressively more humid and overcast. However, fog is most frequent in winter and spring, with 106 days per year reporting some fog. Early spring is the cloudiest time of year, and rainfall begins to dramatically increase in April; the rainy season lasts until late September to early October. The monsoon reaches its peak intensity in the summer months, when the city also experiences very humid, and hot, but moderated, conditions; there are only 2.4 days of 35 °C (95 °F)+ temperatures.[66] The region is prone to torrential rain as well, with 9.7 days that have 50 mm (1.97 in) or more of rain, and 2.2 days of at least 100 mm (3.94 in).[66] The latter portion of autumn is dry. The annual precipitation averages at around 1,970 mm (78 in), some of which is delivered in typhoons that strike from the east during summer and early autumn. Extreme temperatures have ranged from 0.2 °C (32 °F) on 11 February 1957 to 38.7 °C (102 °F) on 10 July 1980.[67]

| Climate data for Shenzhen (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.1 (84.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.9 (98.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.1 (98.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.8 (85.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

29.2 (84.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 26.4 (1.04) |

47.9 (1.89) |

69.9 (2.75) |

154.3 (6.07) |

237.1 (9.33) |

346.5 (13.64) |

319.7 (12.59) |

354.4 (13.95) |

254.0 (10.00) |

63.3 (2.49) |

35.4 (1.39) |

26.9 (1.06) |

1,935.8 (76.2) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 7.1 | 10.1 | 10.8 | 12.7 | 15.6 | 18.5 | 17.0 | 18.3 | 14.8 | 7.6 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 144.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.7 | 76.8 | 79.5 | 81.0 | 81.7 | 81.8 | 80.5 | 81.8 | 78.8 | 72.4 | 68.4 | 67.1 | 76.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 138.7 | 92.4 | 94.9 | 104.6 | 146.4 | 160.3 | 215.6 | 182.5 | 169.9 | 189.6 | 175.8 | 166.9 | 1,837.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 31 | 27 | 29 | 37 | 43 | 53 | 47 | 49 | 55 | 56 | 53 | 44 |

| Source: Shenzhen Meteorological Bureau[66] | |||||||||||||

Politics

| Title | Party Committee Secretary | SMPC Chairman | Mayor | Shenzhen CPPCC Chairman |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Wang Weizhong[68] | Luo Wenzhi[69] | Chen Rugui[70] | Dai Bei[71] |

| Ancestral home | Shuozhou, Shanxi | Foshan, Guangdong | Zhanjiang, Guangdong | Huizhou, Guangdong |

| Born | March 1962 (age 58) | August 1960 (age 59–60) | September 1962 (age 57) | August 1956 (age 63–64) |

| Assumed office | April 2017 | January 2019 | August 2017 | June 2015 |

The politics of Shenzhen is structured in a parallel party-government system,[72] in which the Party Committee Secretary, officially termed the Communist Party of China Shenzhen Municipal Committee Secretary (currently Wang Weizhong), outranks the Mayor (currently Chen Rugui). The party's standing committee acts as the top policy formulation body, and is typically composed of 11 members.

Administrative divisions

Shenzhen has direct jurisdiction over nine administrative Districts and one New District:

| Administrative divisions of Shenzhen | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code[73] | Division | Area in km2[74] | Population 2014[75] | Seat | Postal code | Subdivisions | |||

| Subdistricts | Residential communities | ||||||||

| 440300 | Shenzhen | 1996.78 | 10,779,215 | Futian | 518000 | 74 | 775 | ||

| 440303 | Luohu | 78.75 | 953,764 | Huangbei Subdistrict | 518000 | 10 | 115 | ||

| 440304 | Futian | 78.65 | 1,357,103 | Shatou Subdistrict | 518000 | 10 | 115 | ||

| 440305 | Nanshan | 185.49 | 1,135,929 | Nantou Subdistrict | 518000 | 8 | 105 | ||

| 440306 | Bao'an | 398.38 | 2,736,503 | Xin'an Subdistrict | 518100 | 10 | 123 | ||

| 440307 | Longgang* | 387.82 | 1,975,215 | Longcheng Subdistrict | 518100 | 11 | 111 | ||

| 440308 | Yantian | 74.63 | 216,527 | Haishan Subdistrict | 518081 | 4 | 23 | ||

| 440309 | Longhua | 175.58 | 1,434,593 | Guanlan Subdistrict | 518110 | 6 | 100 | ||

| 440310 | Pingshan | 167.00 | 311,557 | Pingshan Subdistrict | 518118 | 6 | 30 | ||

| 440311 | Guangming | 155.44 | 504,203 | Guangming Subdistrict | 518107 | 6 | 28 | ||

| Dapeng | 295.05 | 133,821 | Dapeng Subdistrict | 518116 | 3 | 25 | |||

| Qianhai | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | Guangdong Romanization | Kejiahua Pinyin Fang'an |

| Shenzhen City | 深圳市 | Shēnzhèn Shì | sem1 zen3 xi5 | cim1 zun4 si4 |

| Luohu District | 罗湖区 | Luóhú Qū | lo4 wu4 kêu1 | lo2 fu2 ki1 |

| Futian District | 福田区 | Fútián Qū | fug1 tin4 kêu1 | fuk5 tien2 ki1 |

| Nanshan District | 南山区 | Nánshān Qū | nam4 san1 kêu1 | lam5/nam5 san1 ki1 |

| Bao'an District | 宝安区 | Bǎo'ān Qū | bou2 on1 kêu1 | bau3 on1 ki1 |

| Longgang District | 龙岗区 | Lónggǎng Qū | lung4 gong1 kêu1 | lung2 gong1 ki1 |

| Yantian District | 盐田区 | Yántián Qū | yim4 tin4 kêu1 | yam2 tien2 ki1 |

| Longhua District | 龙华区 | Lónghuá Qū | lung4 wa4 kêu1 | lung2 fa2 ki1 |

| Pingshan District | 坪山区 | Píngshān Qū | ping4 san1 kêu1 | piang2 san1 ki1 |

| Guangming District | 光明区 | Guāngmíng Qū | guong1 ming4 kêu1 | gong1 min2 ki1 |

| Dapeng New District | 大鹏新区 | Dàpéng Xīnqū | dai6 pang4 sen1 kêu1 | tai4 pen2 sin1 ki1 |

| Qianhai | 前海 | Qiánhǎi | qin4 hoi2 | |

Special Economic Zone Border

To enforce law and order in the city, the Shenzhen government erected barbed wire and checkpoints between the land borders of the main sections of the SEZ and the SEZ outskirts, as well as the rest of China, in 1983, which was known as the second line (Chinese: 二线关).[50][51] Initially, the border control was relatively strict, requiring non-Shenzhen citizens to obtain special permissions for entering. Over the years, border controls have gradually weakened, and permission requirement has been abandoned.

On 1 July 2010, the original SEZ border control was cancelled, and the Shenzhen SEZ was expanded to the whole city.[58] The area of Shenzhen SEZ thus increased from 396 square kilometres (153 sq mi) to 1,953 square kilometres (754 sq mi).[76] Since June 2015 the existing unused border structures have been demolished and are being transformed into urban greenspaces and parks.[77][78][79] On 15 January 2018, the State Council approved the removal of the barbed wire fence set up to mark the boundary of the SEZ.[80][81] Although the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone have been extended to cover the whole of Shenzhen, colloquially Shenzhen is still said to be separated into two areas, with the original four districts comprising the SEZ before 2010 as "simplified Chinese: 关内; traditional Chinese: 關內; pinyin: guān nèi; Jyutping: gwaan1 noi6; lit.: 'within the border') and the rest known as "关外; 關外; guān wài; gwaan1 ngoi6; 'outside of the border').[82]

Economy

Shenzhen was the first of the Special Economic Zones (SEZ) to be established by paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.[83][84] As a SEZ, Shenzhen is given the privilege to embrace market capitalism policies under the guise of "Socialism with Chinese Characteristics," unlike other cities in Mainland China which is based on a planned economy.[85] As of 2018, Shenzhen has a nominal GDP of 2.42 trillion RMB (HK$2.87 trillion), which recently had surpassed neighboring Hong Kong's GDP of HK$2.85 trillion and Guangzhou's GDP of 2.29 trillion RMB (HK$2.68 trillion),[86][87][88] making the economic output of Shenzhen the third largest out of Chinese cities,[89] trailing behind Shanghai and Beijing.[90] In addition, Shenzhen's GDP growth between 2016 and 2017 of 8.8% surpassed that of Hong Kong and Singapore, with 3.7% and 2.5% respectively.[91] With a market capitalization of US$2.5 trillion as of 30 November 2018, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) is the 8th largest exchange in the world.[92]

Industry

Shenzhen's industry is described by its Municipal Bureau of Statistics to be upheld by its four-pillar industries: high-tech, finance, logistics, and culture.[93] Shenzhen is primarily known for its high-tech industry, which has a value of 585.491 billion RMB (US$82.9 billion) in 2015, a 13% increase compared to last year.[93] Out of the nominal GDP of 1,750.299 billion RMB in 2015, the high-tech industry comprises 33.4% of this amount. Shenzhen is home to a number of prominent tech firms, such as telecommunications and electronics corporation Huawei,[94] internet giant and holding conglomerate Tencent,[95] drone-maker DJI,[96] and telecommunications company ZTE.[97] Shenzhen annually holds the China International High-tech Achievements Fair, which showcases high-tech products and provides for dialogue and investment for high-tech.[98] As a result, Shenzhen is dubbed by media outlets as "China's Silicon Valley"[99][100] or the "Silicon Valley of Hardware" for the world.[101][102]

In addition to its numerous high-tech companies, Shenzhen is also home to a number of large financial institutions, such as China Merchants Bank[103] and Ping An Insurance[104] and its subsidiary Ping An Bank.[105] Since the city's establishment as a SEZ, a number of foreign banks had established offices in the city, including Citibank, HSBC, Standard Chartered, and Bank of East Asia.[106] In total, the financial industry accounts for 14.5% of the city's nominal GDP in 2015 (254.282 billion RMB), which was a 15.9% increase over the previous year.[93] By the end of 2016, the total assets of the financial industry amounted to 12.7 trillion RMB (banking industry assets were 7.85 trillion RMB, security companies assets were 1.25 trillion RMB, and insurance industry assets were 3.6 trillion RMB), making Shenzhen's financial industry the third largest in China.[107] In addition, Shenzhen is one of the world's top ten financial centers as of 2019, jumping five places to ninth place as determined by "variety of areas of competitiveness, including business environment, human capital, infrastructure, financial sector development and reputation."[108]

Addressing the logistics industry, courier SF Express and shipping company China International Marine Containers (CIMC) have their headquarters in Shenzhen.[109][110] The Port of Shenzhen, composed of Yantian International Container Terminals, Chiwan Container Terminals, Shekou Container Terminals, China Merchants Port and Shenzhen Haixing (Mawan port), handled a record number of containers with rising trade increased cargo shipments in 2005, ranking it as the world's third-busiest port.[111][112] Together, the logistics industry accounts for around 10.1% (178.27 billion RMB) of the city's nominal GDP in 2015, which was an increase of 9.4%.[93]

Shenzhen had prioritized the cultural industry in according to the 13th Five-Year Plan, establishing the Shenzhen Fashion Creative Industry Association and planning the 4.6 square-kilometer Dalang Fashion Valley.[113][114] On 7 December 2008, UNESCO approved Shenzhen's entrance into the Creative Cities Network, and awarded the Shenzhen the title of "United Nations Design Capital."[115] Altogether, the cultural industry in turn contributes to 5.8% (102.116 billion RMB) of Shenzhen's economy in 2015.

In addition to the four pillar industries that was listed by the municipal government, Shenzhen also has a relatively notable real-estate industry.[116] The real-estate industry altogether contributes to 9.2% (162.777 billion RMB) of Shenzhen's economy in 2015, which was an increase of 16.8% compared to last year.[93] Real estate developers such as Vanke[117] and China Resources Land[118] are headquartered within the city.

As a SEZ, Shenzhen has established several industrial zones to encourage economic activities. The Shekou Industrial Zone was approved and established back in 31 January 1979 by the Central Committee of the CPC to assist in the "Hong Kong-based" economy of Shenzhen.[43] In 1996, the State Council approved and established the 11.5 km2 (4.4 sq mi) Shenzhen High-tech Industrial Development Zone, helping to develop Shenzhen's high-tech industry in areas such as electronics and information technology.[119] In accordance to the National Plan in 2001, the Shenzhen Software Park, integrated within the High-tech Industrial Development Zone, was established for software production and assist in the development of the city's software industry.[120] On 26 August 2010, the State Council approved the "Overall Development Plan for Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone" to solidify ties between Hong Kong and Shenzhen.[59][121]

Tourism

Tourism is gradually growing as an important industry for Shenzhen. Shenzhen has been ranked second on the list of ‘top 10 cities to visit in 2019' by Lonely Planet.[13] The Shenzhen administration in its "12th Five-Year Plan for Tourism Development of Shenzhen" had focused on turning the city into an international tourist hub, with emphasis on the city's scientific, fashion, and industrial elements.[122] The Shenzhen tourist industry is claimed by the local administration in having a strong development advantage, due to the city being one of the tier-one cities in China, as well as being known for its coastal resources, climate environment, capitalist economy, and technological innovation.[123] In 2015, the tourism industry's total revenue was 124.48 billion RMB (US$17.6 billion), a 98.1% increase from 2010. Out of the total revenue, 28% (35 billion RMB or US$4.968 billion) came from international tourists, an increase of 56.2% from 2010. In addition, in that year, Shenzhen received 11.63 million tourists, a 51% increase from 2010.

Shenzhen has numerous tourist destinations, ranging from recreational areas such as theme parks and public parks to tall buildings. Most of the tourist attractions are part of Overseas Chinese Town (OCT), a colloquial name for parks owned by OCT Enterprises and is classified as an AAAAA scenic area by the China National Tourism Administration.[124] These include the Window of the World,[125][126] the Splendid China Folk Village,[127][128] Happy Valley (欢乐谷),[129][130] OCT East,[131] and OCT Harbour.[132] Other theme parks include Shekou Sea World (海上世界),[133][134] Xiaomeisha Sea World,[135][136] and the now-closed Minsk World.[137][138] Shenzhen also has a number of popular public parks and beaches, such as People's Park, Lianhuashan Park, Lizhi Park, Zhongshan Park, Wutongshan Park, Dameisha (大梅沙; 'big mesa') and Xiaomeisha (小梅沙; 'small mesa').[139][140] The city is also home to tall buildings such as the Ping An Finance Centre,[141] KK100,[142] and the Shun Hing Square (also known as Di Wang Tower).[143]

Shenzhen's tourism industry is recently expanding under the "13th Five-Year Plan for Tourism Development of Shenzhen" as promoted under the Shenzhen local government.[122] In this plan, the tourist industry plans to exceed 200 billion RMB and receive 150 million domestic and foreign tourists by 2020.[123] Part of the plan includes organizing the tourist industry within five brands: theme parks, retail, natural recreational areas, sports, and international gatherings, as well as speeding up construction of future tourist attractions and turning Shenzhen into a Chinese hub for sports.

Retail

Retail is an important pillar of Shenzhen's tertiary sector. Out of the added value of Shenzhen's tertiary sector of 1.42 trillion RMB (US$201 billion), retail contributed 43% (616.89 billion RMB) of this amount, a 7.6 percent increase compared to last year (601.62 billion RMB).[144] In addition, 10.9% of Shenzhen's FDI is directed towards the wholesale and retail sector.

Huaqiang North (华强北) is one of Shenzhen's notable retail areas, being known for having one of the largest electronics markets in the world.[145] Luohu Commercial City, a commercial complex located adjacent to Shenzhen Railway Station, is noted for having a variety of products that ranges from electronics and counterfeit goods to tailored suits and curtains.[141] In addition to Huaqiang North and Luohu Commercial City, Shenzhen has numerous shopping malls and commercial areas, including COCO Park and its branches COCO City and Longgang COCO Park,[146][147] Uniworld (壹方天地),[148] Uniwalk (壹方场),[149] and Coastal City(海岸城).[150]

"Smart retail", which uses technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data in production, circulation, and sales of consumer goods, has been growing popular within enterprises in Shenzhen.[151] Businesses in Shenzhen are encouraged to use the Internet to develop the consumer market and new retail projects would be assisted with the use of technology. In addition, the Shenzhen administration is setting up a new retail industry development fund to promote the use of "smart retail", with the intention of stimulating the economy of Shenzhen and to turn the city into a "new retail" hub.

Innovation

Shenzhen is considered as a major innovation hub of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Over the years it has become one of the most important research and development (R&D) and manufacturing centers in the country.

Demographics

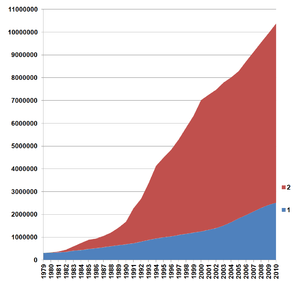

Legend:

Shenzhen is the fifth most populous city proper in China, with a population of 12,528,300 in the city as of 2017.[152] With a total area of 1,992 km²,[153] Shenzhen has a population density of 6,889 inhabitants per square kilometre. The encompassing metropolitan area of the city was estimated by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) to have, as of 2010, a population of 23.3 million.[3][154] Shenzhen is part of the Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region (covering cities such as Guangzhou, Dongguan, Foshan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai, Huizhou, Hong Kong, and Macau), the world's largest urban area according to the World Bank,[155] and has a population of over 108.5 million according to the 2015 census.[156]

Before Shenzhen's establishment as a SEZ in 1980, the area was composed mainly of Hakka and Cantonese people.[157] However, since become a SEZ, Shenzhen has become a hub for migrants searching for work and opportunities within the city.[158]

Historic

There had been migration into southern Guangdong province and what is now Shenzhen since the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) but the numbers increased dramatically since Shenzhen was established in the 1980s. In Guangdong province, it is the only city where the local languages (Cantonese, Shenzhen-Hakka and Teochew) is not the main language; it is Mandarin that is mostly spoken, with migrants/immigrants from all over China.

Shenzhen has seen its population and activity develop rapidly since the establishment of the SEZ as a magnet for migrants, beginning with blue collar or labor-intensive workers, giving the city the moniker of the world's factory. Shenzhen had an official population of over 10 million during the 2011 census. However, due to the large unregistered floating migrant population living in the city, some estimates put Shenzhen's actual population at around 20 million inside the administrative area given at any specific moment.[16][17] The population growth of Shenzhen follows large scale trends; around 2012–13, the city's estimated growth slowed down to less than 1 percent due to rising migrant labor costs, migrant worker targeted reforms, and moving of factories out to periphery and neighboring Dongguan. By 2015, the high tech economy began to gradually replace the labor-intensive industries as the city gradually became a magnet for a new generation of migrants, this time educated, white collar workers. Migration into Shenzhen was further promoted by hard population caps imposed on other Tier I cities like Beijing and Shanghai, previously the top destinations for white collar workers. By the end of 2018, the official registered population had been estimated as just over 13 million a yoy increase of 500,000.[159]

Other statistics

At present, the average age in Shenzhen is less than 30. The age range is as follows: 8.49% between the age of 0 and 14, 88.41% between the age of 15 and 59, and 3.1% aged 65 or above.[160]

The population structure has great diversity, ranging from intellectuals with a high level of education to migrant workers with poor education.[161] It was reported in June 2007 that more than 20 percent of China's PhD graduates had worked in Shenzhen.[162] Shenzhen was also elected as one of the top 10 cities in China for expatriates. Expatriates choose Shenzhen as a place to settle because of the city's job opportunities as well as the culture's tolerance and open-mindedness, and it was even voted China's Most Dynamic City and the City Most Favored by Migrant Workers in 2014.

According to a survey by the Hong Kong Planning Department, the number of cross-border commuters increased from about 7,500 in 1999 to 44,600 in 2009. More than half of them lived in Shenzhen.[163] Though neighboring each other, daily commuters still need to pass through customs and immigration checkpoints, as travel between the SEZ and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) is restricted.

Mainland residents who wish to enter Hong Kong for visit are required to obtain an "Exit-Entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macao". Shenzhen residents can have a special 1 year multiple-journey endorsement (but maximum 1 visit per week starting from April 13, 2015) This type of exit endorsement is only issued to people who have hukou in certain regions.[164](See Exit-Entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macau.)

Ethnic groups

Koreans

As of 2007 there were about 20,000 people of Korean origins in Shenzhen, with the Nanshan and Futian districts having significant numbers. That year the chairperson of the Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kang Hee-bang, stated that about 10,000 lived in Overseas Chinese Town (OCT). Shekou, the area around Shenzhen University, and Donghai Garden housing estate had other significant concentrations.[165] Donghai Garden began attracting Koreans due to its transportation links and because, around 1998, it was the sole residential building classified as 3-A. As of 2014 Donghai had about 200 Korean families.[166]

South Koreans began going to the Shenzhen area during the 1980s as part of the reform and opening up era, and this increased when South Korea established formal diplomatic relations with the PRC.[166]

In 2007 about 500 South Korean companies in Shenzhen were involved in China-South Korean trade, and there were an additional 500 South Korean companies doing business in Shenzhen. In 2007 Kang stated that most of the Koreans in Shenzhen had lived there for five years or longer.[165]

There is one Korean international school in Shenzhen, Korean International School in Shenzhen. As of 2007 there were some Korean children enrolled in schools for Chinese locals.[165] As of 2014 spaces for foreign students in Shenzhen public schools were limited, so some Korean residents are forced to put their children in private schools.[166] In addition, in 2007, there were about 900 Korean children in non-Chinese K-12 institutions; the latter included 400 of them at private international schools in Shekou, 300 in private schools in Luohu District, and 200 enrolled at the Baishizhou Bilingual School. Because many Korean students are not studying in Korean-medium schools, the Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry operates a Korean Saturday School; it had about 600 students in 2007. The chamber uses rented space in the OCT Primary School as the Korean weekend school's classroom.[165]

Languages and religions

Prior to the establishment of Special Economic Zone, the indigenous local communities could be divided into Cantonese and Hakka speakers,[167] which were two cultural and linguistic sub-ethnic groups vernacular to Guangdong province. Two Cantonese varieties were spoken locally. One was a fairly standard version, known as standard Cantonese. The other, spoken by several villages south of Fuhua Rd. was called Weitou dialect.[168] Two or three Hong Kong villages south of the Shenzhen River also speak this dialect. This is consistent with the area settled by people who accompanied the Southern Song court to the south in the late 13th century.[169] Younger generations of the Cantonese communities now speak the more standard version. Today, some aboriginals of the Cantonese and Hakka speaking communities disperse into urban settlements (e.g. apartments and villas), but most of them are still clustering in their traditional urban and suburban villages.[170]

The influx of migrants from other parts of the country has drastically altered the city's linguistic landscape, as Shenzhen has undergone a language shift towards Mandarin, which was both promoted by the Chinese Central Government as a national lingua franca and natively spoken by most of the out-of-province immigrants and their descendants.[171][172][173] However, in recent years multilingualism is on the rise as descendants of immigrants of out-of-province Mandarin native speakers begin to assimilate into the local culture through friends, television and other media.[174] Despite the ubiquity of Mandarin Chinese, local languages such as Cantonese, Hakka, and Teochew are still commonly spoken among locals. Hokkien and Xiang are also sometimes observed.

According to the Department of Religious Affairs of the Shenzhen Municipal People's Government, the two main religions present in Shenzhen are Buddhism and Taoism. Every district also has Protestant churches, Catholic churches, and mosques.[175] According to a 2010 survey held by the University of Southern California, approximately 37% of Shenzhen's residents were practitioners of Chinese folk religions, 26% were Buddhists, 18% Taoists, 2% Christians and 2% Muslims; 15% were unaffiliated to any religion.[176] Most new migrants to Shenzhen rely upon the common spiritual heritage drawn from Chinese folk religion.[177][178] Shenzhen also hosts the headquarters of the Holy Confucian Church, established in 2009.[179]

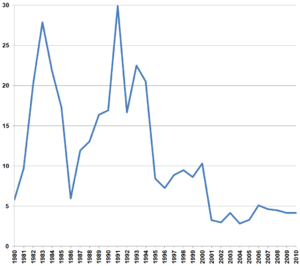

Crime

In general, Shenzhen is a relatively safe city. However, in districts such as Bao'an and Longgang, the number of robberies, extortion, kidnapping, and fraud exceeds the national average. In the central part of the Luohu District, especially in the neighborhoods around the Shenzhen Railway Station, Shenzhen Bus Terminal, and the Luohu Commercial City Shopping Center, pickpocketing, prostitution, drug trafficking, fraud, and the sale of counterfeit bills are common. In addition, Luohu is a major center for trade in counterfeit goods and abundant in its nightclubs, bars, and karaoke salons, which not only attracts Shenzhen residents, but also residents from neighboring Hong Kong, which may attract criminal elements. The Nanshan District has a large concentration of foreigners, and is known for its abundance of prostitutes and beggars. Along with local gangs in Shenzhen, there is a notable presence of triads: notably Wo Shing Wo, Big Circle Gang, Sun Yee On, 14K, and Shui Fong.[180][181][182][183] The level of corruption in the government is usually high, as seen in the arrest of the then-mayor of Shenzhen, Xu Zongheng,[184] for accepting bribes in June 2009, as well as arrests and convictions of Li Yugo, the former head of the largest state-owned construction corporation in the city, and Zhao Yutsun, a customs officer of the city, for the same reasons.[185]

Cityscape

Shenzhen has been dubbed by The Guardian as "the world leader completing new skyscrapers," as it managed to complete 14 skyscrapers that are above 200 meters in 2018, four more than Dubai, and keeping this title for three years.[186][187] In addition, the city is home to the most number of skyscrapers above 200 meters than any other cities in the world, with 82 completed as of July 2019.[188] The city is ranked the third in the world in terms of the number of buildings above 150 meters, with 223 of them completed as of July 2019, after Hong Kong and New York City.[189] There were more skyscrapers completed in Shenzhen in the year 2016 than in the whole of the US and Australia combined.[190] The construction boom continues today with over 60 skyscrapers under construction across the city as of 2019.[191] The tallest building in Shenzhen is the 599-meter, 115 floor Ping An Finance Centre, which is also the second tallest in China and the fourth tallest building in the world.[192] The second-tallest building is the Kingkey 100, rising 441.8 metres (1,449 ft) and containing 100 floors of office and hotel spaces.[193] Shenzhen is also the home to the Shun Hing Square (Diwang Building), the tallest in Asia (if the antenna is taken into account) when it was built in 1996.[194][195] Guomao Building was furthermore the tallest building in China when it was completed in 1985.[196]

In addition to the Shenzhen's modern skyscrapers, Shenzhen also has a significant number of historical buildings. Chiwan Fort is located on a small seaside hill in the Nanshan District. Today, what is left only represents a fragment of the large fortress, as it was partially destroyed by the British during the Opium Wars.[197] Tianhou Temple in the Nanshan District is dedicated to the goddess Mazu, a tutelary deity for fishermen and sailors. According to legend, the temple was founded in 1410 by Admiral Zheng He after his fleet survived a strong storm in the Pearl River Delta. The temple is repeatedly rebuilt and repaired. Part of the temple was converted to a museum, but the rest still continues to function as a religious building.[198] The tomb of the last emperor of the Southern Song Dynasty, Zhao Bing, is located in the Nanshan district. The modern tomb dates back to the end of the 19th century, when a Hong Kong clan announced one of the imperial tombs after a long search, though this is disputed by historians. The tomb was reconstructed at the beginning of the 20th century, but later it fell into neglect until it was restored again in the 1980s.[199][200] Dapin Fortress is located in the eastern part of the city, in the same area. It was built in 1394 to protect the coast from pirates and in 1571 suffered a long siege of Japanese corsairs. It later turned into a typical town during the Qing Dynasty, and during the First Opium War, the fortress garrison participated in the fight against the British. Walls and gates, narrow streets, temples, and the residence of the commandant in the fortress are still preserved today.[201] There is an old fortified Hakka village in the Longgang District, whose the architectural features of which are complemented by the Hakka Culture Museum.[202][203]

The old town of Nantou (or Xin'an), located in the Nanshan District, has several historical sites dating back to the Ming and Qing Dynasties. From the 4th century, there existed a significant city, but today most of the old buildings have been replaced by modern buildings. However, there are still a few historical buildings, such as fortress walls and gates dating back to the Ming period, the Guandi Temple (Guan Yu), some military and civilian buildings (for example, the residence of officials, the shop, and the opium house), and several streets.[204][205][206]

Parks and beaches

Shenzhen offers free admission to over of its twenty public city parks[139] such as People's Park, Lianhuashan Park, Lizhi Park, Zhongshan Park, and Wutongshan Park. The Xianhu Botanical Garden (仙湖; 'Fairy Lake'), founded in 1982, is spread around the lake of the same name in the Luohu District on an area of 590 hectares. On one of the hills of the garden is Hunfa Temple, the largest Buddhist temple in Shenzhen, which was built in 1985 on the site of an older shrine. Around the lake are a pagoda, tea houses, pavilions, the Museum of Paleontology, a garden of medicinal plants and an azalea garden.[207][208] Wutongshan National Park (梧桐山) is spread around the mountain of the same name in the Luohu District. From the observation deck, there is a view of the Shenzhen skyline as well as Hong Kong and the surrounding bay, and on the next peak there is a transmission tower of a local television station.[209] Lianhuashan Park (莲花山; Lotus Hill) is located on the territory of 150 hectares in the Futian District. At the top of the mountain is a large bronze statue of Deng Xiaoping.[210][211][212] The Shenzhen Garden and Flower Exposition Center, established in the Futian District in 2004 for the International Garden Exhibition, has many gardens of various styles, artificial ponds and waterfalls, a pagoda, pavilions, and statues.[213] The Shenzhen Bay Park opened in 2011 which included the nearby Mangrove Park. There are several thematic recreation areas and attractions, and along the 9-kilometer-long coastal strip there is an embankment.[214][215] The Mangrove Ecopark was established in 2000 in the Futian District and at that time was the smallest national park in China. A large group of birds migrate to the ecopark in the mangroves on an area of 20.6 hectares in a 9-kilometer coastal zone of the Shenzhen Bay.[216] The Shenzhen Safari Park in the Nanshan District combines a zoo and a large zoological center on a territory of 120 hectares.[217][218] Xili Lake Resort (西丽湖), located in the Nanshan District, has a park with springs and waterfalls stretching around the lake, surrounded by a canopy, and a pagoda and a pavilion located on the top of Xili Mountain.[219] Zhongshan Park (中山), located in the Nanshan District, is the city's oldest park. It has several artificial lakes and ponds, an old city wall dating back to the 14th century, and many sculptures and monuments, including one of Sun Yat-sen. The Yangtai Mountain Forest Park is located around the 500-meter Yangtai Mountain (羊台山) in the Bao'an District. Nearby the mountain is Shiyan Lake (石岩湖), which became a popular place of Xin'an County in the 16th century. It is famous for its several indoor and outdoor pools with hot thermal waters.[220][221]

Shenzhen has several beaches: Dameisha (大梅沙; 'big mesa') and Xiaomeisha (小梅沙; 'small mesa') in the Yantian District, and Jinshawan (金沙湾; 'golden sands bay'), Nan'ao (南澳; 'southern inlet'), and Xichong (西冲) in Dapeng Peninsula (in the vicinity of Dapeng New District, which is administered by the Longgang District).[140]

Education

Before the 1980s, Shenzhen's education system was primarily based on primary and limited secondary schooling, with no residents admitted to a university.[222] Since Shenzhen's establishment as a SEZ in the 1980s, migrants poured into the city, and jobs requiring a university education grew. Shenzhen started implementing policies that will help develop a more high-quality education system, borrowing teachers from the best schools in the country with promises of higher pay and benefits. In addition, the city started building new schools and renovating the infrastructure of its existing schools to give teachers a more comfortable environment to teach.

In the mid-1980s, as upper secondary education became popular, there was a need for higher education institutions in the city.[222] Opened in 1983, Shenzhen Normal School, later upgraded to Shenzhen Normal College, trained students to become primary school teachers. Approved by the State Council in the same year, Shenzhen University became Shenzhen's first comprehensive full-time higher educational institution.[223][224] In 1999, the Shenzhen Municipal Government set up the Shenzhen Virtual University Park in the Science and Technology Park, where teachers from China's top universities taught graduate students.[225] In 2011, the innovative Southern University of Science and Technology was established[226] followed in 2018 by the Shenzhen Institute of Technology.[227] Other universities have established campuses in the city, including the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the Harbin Institute of Technology, and Moscow State University.[228]

The 9-year compulsory education in Shenzhen is free.[229][230] Secondary schools such as Shenzhen Middle School, Shenzhen Experimental School, Shenzhen Foreign Languages School, and Shenzhen High School, all of which have an on-line rate of over 90%, are dubbed as "Shenzhen's four famous schools."[231] As of 2015, Shenzhen has 12 higher educational institutions, 335 general secondary schools, 334 primary schools, and 1,489 preschools.[232]

According to Laurie Chen of the South China Morning Post, Shenzhen, which had 15 million people as of 2019, had not built as many primary and secondary schools for its populace as it should have, compared to similarly developed cities in China.[233] Laurie Chen cited the acceptance rate of Shenzhen secondary schools in 2018: 35,000 slots were available for almost 80,000 applicants. She also cited how Guangzhou had 961 primary schools while Shenzhen had only 344 primary schools, as well as how Guangzhou's count of primary school teachers exceeded that of Shenzhen's by 17,000; Chen argued that Guangzhou and Shenzhen have similar populations. In response Shenzhen schools began increasing salaries for prospective teachers.[233]

Transport

Shenzhen is the second largest transportation hub in Guangdong and South China, trailing behind the provincial capital of Guangzhou.[234] Shenzhen has a developed extensive public transportation system, covering rapid transit, buses and taxis,[235] most of which can be accessed by either using a Shenzhen Tong card or using QR codes generated by WeChat mini programs.[236][237][238]

Regarding air transport, Shenzhen is served by its own Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport and the neighboring Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA). Located 35 kilometres (22 miles) from the center of the city, Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport serves as the main hub for passenger airlines Shenzhen Airlines[239] and Donghai Airlines[240] and a main hub for cargo airlines Jade Cargo International,[241] SF Airlines,[242] and UPS Airlines.[243] Together, Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport handled 49,348,950 passengers, 355,907 aircraft, and 1,218,502.2 cargo in 2018, making it the 5th busiest airport in China in terms of passenger traffic and the 4th busiest airport in the country in terms of aircraft and cargo traffic.[244] In addition to flying through Bao'an International Airport, ticketed passengers can also take ferries from the Shekou Cruise Centre and the Fuyong Ferry Terminal to the Skypier at Hong Kong International Airport.[245] There are also coach bus services connecting Shenzhen with HKIA.[246]

The Shenzhen Metro serves as the city's rapid transit system. The extension opened on 8 December 2019 put the network at 303.4 kilometres (188.5 miles) of trackage operating on 8 lines with 215 stations.[247] By 2030 the network is planned to be 8 express and 24 non-express lines totalling 1142 kilometres of trackage.[248][249][250] The average daily metro ridership in 2016 is 3.54 million passengers, which accounts for a third of public transportation users in the city.[251] The metro also operates a tram system in the Longhua District.[252]

Shenzhen is served by seven inter-city railway stations: Futian,[253] Guangmingcheng,[254] Pingshan,[255] Shenzhen (also known as Luohu Railway Station)[256][257] Shenzhen East,[258] Shenzhen North,[259][260] and Shenzhen West.[261] High-speed rail (HSR) lines that go through the city are the Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link,[262] the Beijing–Guangzhou high-speed railway,[263] and the Xiamen–Shenzhen railway (forms part of the Hangzhou–Fuzhou–Shenzhen passenger railway).[264] Non-HSR lines that go through Shenzhen are the Guangzhou-Shenzhen Railway (forms part of the Kowloon–Canton railway)[265] and the Beijing-Kowloon Railway.[266]

As of August 2019, the city's bus system encompasses over 900 lines,[267] with a total of over 16,000 electric vehicles, the largest of its kind in the world.[268] The system is operated by multiple companies.[269] As at January 2019 conversion of Shenzhen's taxi fleet to electric vehicles reached 99%.[270] Electric taxis have a blue and white colour scheme. Petroleum fuelled taxis are coloured either green or red.[271][272]

Shenzhen serves as a fabric to China's expressway system. Expressways within the city include the Meiguan Expressway (part of the G94 Pearl River Delta Ring Expressway),[273] the Jihe Expressway (part of the G15 Shenhai Expressway),[274][275] the Yanba Expressway (part of the S30 Huishen Costal Expressway),[276] the S28 Shuiguan Expressway,[277] the Yanpai Expressway (part of the G25 Changshen Expressway and the S27 Renshen Expressway),[278] and the S33 Nanguang Expressway.[279] In response to being rejected from being a part of the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge, Shenzhen is constructing a bridge across the Pearl River Delta to connect the city of Zhongshan.[280][281]

Private car ownership has been on the rise in Shenzhen, with the city having over 3.14 million cars in 2014.[282] In response, the city imposed limits on car purchases to reduce traffic and pollution. The purchase of electric cars will be determined by a lottery, while traditional cars will be determined both a lottery and a bidding process. In addition, the city banned passenger vehicles with license plates issued in other places from four of Shenzhen's main districts during peak times on working days as of 29 December 2014.

Shenzhen is connected with Hong Kong (city and airport), Zhuhai and Macau through ferries that leave from and arrive at the Shekou Cruise Center.[283] The Fuyong Passenger Terminal in the Bao'an District provide services to and from Hong Kong (Hong Kong International Airport) and Macau (Taipa Temporary Ferry Terminal and Outer Harbour Ferry Terminal).[284] The Port of Shenzhen is the third busiest container port in the world, handling 27.7 million TEUs in 2018.[285][286]

Due to its proximity to Hong Kong, Shenzhen has the largest number of entry and exit ports, the largest number of entry and exit personnel, and the largest traffic volume in China.[287] Shenzhen is busiest in China when it comes to border crossings, with people entering and exiting the country through the city and Hong Kong reaching 239 million in 2015.[288] In the same year, a total of 15.5 million vehicles crossed the border in Shenzhen, a 0.4% increase of last year. Border crossing ports include the Shenzhen Bay Port, Futian Port, Huanggang Port, Man Kam To Port, and Luohu Port.

Culture

.jpg)

As Shenzhen is located in Guangdong, the city historically has a Cantonese culture before its transition to a SEZ.[289] Migrants coming to the city to find work and opportunities have turned Shenzhen into a cultural melting pot.[290][291] Despite this, the municipal government and some of the residents living in Shenzhen, including those who are not from Guangdong, have invested in keeping and reflecting off the city's Cantonese heritage. Shenzhen has presented itself as a city of opportunity for young people in China.[292] The competitive culture that the city promotes among the youth have resulted in the term "Shenzhen speed," which describes a period of constant competition, quick changes, and high-efficiency.[293]

In 2003, the municipal government announced plans to turned Shenzhen into a cultural city by promoting design, animation, and library construction.[294] The municipal government also intends to develop the city's cultural industry in accordance to the 13th Five-Year Plan, establishing the Shenzhen Fashion Creative Industry Association and the 4.6 square-kilometer Dalang Fashion Valley.[295][114] Shenzhen's cultural industry specializes in being one of the largest handicraft manufacturers in China,[296] and is also an industry center for oil painting in bases such as Dafen Village.[297] Shenzhen also hosts the Shenzhen International Cultural Fair which specializes as an expo for the world's cultural industries, with the first expo being on November 2004.[298][299] As a result of these developments, Shenzhen was awarded by UNESCO the title of "United Nations Design Capital" and was accepted entry into the Creative Cities Network on 7 December 2008.[115]

As part of turning Shenzhen into a cultural city, the municipal government established the "Library City" (图书馆之城) concept in 2003.[300] The plan would create a library network within the city through library construction, service improvement, and create a comfortable reading environment. By the end of 2015, Shenzhen has 620 public libraries, including 3 city-level public libraries, 8 district-level public libraries, and 609 grassroots libraries. Notable libraries include the Shenzhen Library and the Shenzhen Children's Library.[301] Shenzhen also has bookstores, with the most notable being Shenzhen Book City in the Futian District.[302] With an operating area of 42,000 square metres (450,000 sq ft), it claimed to be the largest bookstore of Asia at the time of its opening. Shenzhen has a number of museums and art galleries,[303][304] such as the Shenzhen Museum, the Shenzhen Art Museum, the Shekou Maritime Museum,[305] the Longgang Museum of Hakka Culture, the Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art, and the He Xiangning Art Museum. Shenzhen also has a few theaters, notably the Shenzhen Concert Hall, the Shenzhen Grand Theater, and the Shenzhen Poly Theater.[306]

As with Hong Kong and the surrounding Guangdong province, the main cuisine of Shenzhen is Cantonese.[307] However, due to the recent growth of migrants to the city, Shenzhen also hosts a diverse array of cuisines, from Chinese cuisines such as Chaozhou cuisine, Hakka cuisine, Sichuan Cuisine, Hu Cuisine, and Xiang Cuisine, as well as foreign cuisines such as Korean, Japanese, French, and American.[308] The Yantian District is known for its Chaozhou-based and Hakka-based seafood, with restaurants lined up along the coastline. Some recreational areas in Shenzhen such as Xianhu Botanical Garden, Donghu Park, and Xiaomeisha, host barbecues where visitors bring their own food. Street food such as Xinjiang lamb skewers, Northern Chinese pancakes, and black sesame soups, can be found in Xijie Street and the urban village of Baishizhou.[308] Shenzhen also has its own tea culture.[309][310] In regards to food chains, first McDonald's restaurant in mainland China opened for business in Shenzhen on 8 October 1990, providing the city American fast food.[311] Shenzhen is home to the HeyTea chain of tea shops, which provides a variety of cheese and fruit teas and is popular among social media.[312][313]

Shenzhen has a prominent nightlife culture, with most of the activity centered in the entertainment complexes of COCO Park and Shekou,[308] with the former being referred by the South China Morning Post (SCMP) as "Shenzhen's answer to Lan Kwai Fong."[314][315] There are many bars and clubs in the city, mostly unregulated, that stay open till the morning. Tunnel raves, referred by the SCMP as "a Shenzhen nightlife staple", have earned a reputation in the world, though they are often cracked down by police. Police has also cracked down on prostitution and pornography, which were elements of nightlife entertainment in Shenzhen, with one of the most prominent operations being centered in Shazui (沙嘴村) in the Futian District in the mid-2000s, resulting in closures of entertainment businesses and a decrease of foreign tourists in that area of the city.[316]

Sports

Shenzhen is the home to professional football team Shenzhen F.C., which participates in both China League One and the Chinese Super League.[317] Another local football team, Shenzhen Ledman F.C., was once a part of China League Two until the club was disbanded in 2018.[318] Shenzhen's top-tier basketball team, the Shenzhen Aviators, plays in the Southern Division of the Chinese Basketball Association. Shenzhen F.C. and the Shenzhen Aviators both are tenants of the Shenzhen Universiade Sports Centre.

Shenzhen Stadium is a multi-purpose stadium that hosts many events. The stadium is located in Futian District and has a capacity of 32,500. It was built in June 1993, at a cost of 141 million RMB. The 26th Summer Universiade was held in Shenzhen in August 2011.[319] Shenzhen has constructed the sports venues for this first major sporting event in the city.[320]

Shenzhen Dayun Arena is a multipurpose arena. It was completed in 2011 for the 2011 Summer Universiade. It is used for the basketball, ice hockey and gymnastics events. The arena is the home of the Shenzhen KRS Vanke Rays of the Canadian Women's Hockey League.

Shenzhen is also a popular destination for skateboarders from all over the world, due to the architecture of the city and its lax skate laws.[321]

The Shenzhen Bay Sports Centre was one of the venues at the 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup.[322]

From 2019 to 2028 Shenzhen is hosting the WTA Finals, a major annual professional tennis tournament for the world's most top-ranked female players.[323]

Relationship with Hong Kong

Hong Kong and Shenzhen have close business, trade, and social links as demonstrated by the statistics presented below. Except where noted the statistics are taken from sections of the Hong Kong Government website.[324]

As of September 2016, there are nine crossing points on the boundary between Shenzhen and Hong Kong, among which six are land connections. From west to east these include the Shenzhen Bay Port, Futian Port, Huanggang Port, Man Kam To Port, Luohu Port and Shatoujiao Port. On either sides of each of these ports of entry are road and/or rail transportation.[325][326]

In 2006, there were around 20,500 daily vehicular crossings of the boundary in each direction. Of these 65 percent were cargo vehicles, 27 percent cars and the remainder buses and coaches. The Huanggang crossing was most heavily used at 76 percent of the total, followed by the Futian crossing at 18 percent and Shatoujiao at 6 percent.[327] Of the cargo vehicles, 12,000 per day were container carrying and, using a rate of 1.44 teus/vehicle, this results in 17,000 teus/day across the boundary,[328] while Hong Kong port handled 23,000 teus/day during 2006, excluding trans-shipment trade.[329]

Trade with Hong Kong in 2006 consisted of US$333 billion of imports of which US$298 billion were re-exported. Of these figures 94 percent were associated with China.[330] Considering that 34.5 percent of the value of Hong Kong trade is air freight (only 1.3 percent by weight), a large proportion of this is associated with China as well.[331]

Also in 2006 the average daily passenger flow through the four connections open at that time was over 200,000 in each direction of which 63 percent used the Luohu rail connection and 33 percent the Huanggang road connection.[326] Naturally, such high volumes require special handling, and the largest group of people crossing the boundary, Hong Kong residents with Chinese citizenship, use only a biometric ID card (Home Return Permit) and a thumb print reader. As a point of comparison, Hong Kong's Chek Lap Kok Airport, the 5th busiest international airport in the world, handled 59,000 passengers per day in each direction.[331]

Hong Kong conducts regular surveys of cross-boundary passenger movements, with the most recent being in 2003, although the 2007 survey will be reported on soon. In 2003 the boundary crossings for Hong Kong Residents living in Hong Kong made 78 percent of the trips, up by 33 percent from 1999, whereas Hong Kong and Chinese residents of China made up 20 percent in 2006, an increase of 140 percent above the 1999 figure. Since that time movement has been made much easier for China residents, and so that group have probably increased further still. Other nationalities made up 2 percent of boundary crossings. Of these trips 67 percent were associated with Shenzhen and 42 percent were for business or work purposes. Of the non-business trips about one third were to visit friends and relatives and the remainder for leisure.[332]

After Shenzhen's attempts to be included in the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge project were rejected in 2004, a separate bridge was conceived connecting Shenzhen on the Eastern side of the Pearl River Delta with the city of Zhongshan on the Western side: the Shenzhen-Zhongshan Bridge.

Qianhai

Qianhai, which means foresea in Chinese language, formally known as the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industries Cooperation Zone, is "a useful exploration for China to create a new opening up layout with a more open economic system."[121] A 15 km2 (5.8 sq mi) area located in western Shenzhen, Qianhai lies at the heart of the Pearl River Delta, adjacent to Shenzhen international airport. Strategically positioned as a zone for the innovation and development of modern services, Qianhai will facilitate closer cooperation between Hong Kong and mainland China, as well as act as the catalyst for industrial reform in the Pearl River Delta.[333] With the goal of loosening capital account restrictions, Qianhai authorities have indicated that Hong Kong banks will be allowed to extend commercial RMB loans to Qianhai-based onshore mainland entities. The People's Bank of China has also indicated that such loans will for the first time not be subject to the benchmark rates set by the central bank for all other loans in the rest of China. According to Anita Fung from HSBC, "This new measure on cross-border lending will enhance the co-operation between Hong Kong and Shenzhen and accelerate cross-border convergence."[121]

Media

Shenzhen has an advanced public media network, boasting one radio station, two TV stations, three broadcasting and TV centers, 19 cable broadcasting and TV sub-stations. In Shenzhen, there are 14 newspapers, one comprehensive publishing house, three video-audio products publishing houses, 88 bureaus of inland and Hong Kong media organizations, 40 periodicals, and about 200 kinds of in-house publications of which the majority belong to enterprises.[334] The most prominent media companies in Shenzhen are the Shenzhen Media Group,[335] the Shenzhen Press Group,[334] China Entertainment Television (CETV),[336] and Phoenix Television branch iFeng.[337]

Shenzhen News (深圳晚报, sznews.com) is a Chinese-language newspaper owned by the Shenzhen Press Group that serves as Shenzhen's main online new source.[338] Shenzhen Daily is an English-language news outlet for Shenzhen. It also covers local, national and international news.[339] That's Shenzhen is the Shenzhen edition of That's PRD, an English-language media company with an online, print and social footprint. That's Shenzhen covers news, arts, lifestyle and events in the city. ShekouDaily.com is an online media outlet providing news and resources that focus on the Shekou sub-district in Nanshan District of Shenzhen.[340]

Sister cities

Shenzhen has been very active in cultivating sister city relationships. In October 1989, Shenzhen Mayor Li Hao and a delegation travelled to Houston to attend the signing ceremony establishing a sister city relationship between Houston and Shenzhen.[341] Houston became the first sister city of Shenzhen. Up to 2015, Shenzhen has established sister city relationship with 25 cities in the world.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Other twinnings

The Shenzhen Port is twinned and has collaboration agreements with:

See also

- Index of Shenzhen-related articles

- Administrative divisions of the People's Republic of China

- Economy of China

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- Pearl River (China)

Notes

- Temporary residency of Chinese citizens up to six months require no registrations.

References

- 2017年深圳经济有质量稳定发展 [In 2017, Shenzhen economy will have stable quality and development] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- OECD Urban Policy Reviews: China 2015, OECD READ edition. OECD iLibrary. OECD Urban Policy Reviews. OECD. 18 April 2015. p. 37. doi:10.1787/9789264230040-en. ISBN 9789264230033. ISSN 2306-9341. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.Linked from the OECD here Archived 9 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.asiatimes.com/2020/01/guangzhou-shenzhen-consolidate-gdp-lead-over-hk/

- "ShenZhen Government Online". Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- "Shenzhen Continues to lead China's reform and opening-up". Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

Shenzhen, [...] which was just a small town when it was chosen as China's first special economic zone to pilot the country's reform and opening-up drive 22 years ago, has now grown into a boomtown, which is placed fourth among Chinese cities in overall economic strength.

- Compare: "The next Silicon Valley? It could be here". Das Netz. 11 July 2017. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

Worldwide, 16 cities are in the starting blocks in the race to become the next Silicon Valley. [...] That Shenzhen is being treated as the Chinese Silicon Valley should come as no surprise.

- Compare: "Shenzhen is a hothouse of innovation". The Economist. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

Welcome to Silicon Delta

- "Shenzhen aims to be global technology innovation hub - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

An important reason Silicon Valley in the US and Israel became world innovation hubs is that they gathered a lot of angel investments. However, Shenzhen lacks angel investments [...].

- The rise of China's 'Silicon Valley' - CNN Video, archived from the original on 2 December 2018, retrieved 1 December 2018

- Rivers, Matt. "Inside China's Silicon Valley: From copycats to innovation". CNN. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Shenzhen". U.S. Commercial Service. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- "Lonely Planet names Shenzhen as a top city to visit in 2019". Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- 昔日边陲小镇深圳的历史渊源. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Fish, Isaac Stone (25 September 2010). "A New Shenzhen". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

Shenzhen grew over the past three decades by capitalizing on both its advantageous coastal location and proximity to Hong Kong and Taiwan (major sources of investment capital), but also on the huge Chinese government support that came with its designation as the first Special Economic Zone.

- Li, Zhu (李注). 深圳将提高户籍人口比例 今年有望新增38万_深圳新闻_南方网. sz.Southcn.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- 深圳大幅放宽落户政策 一年户籍人口增幅有望超过10%. finance.Sina.com.cn. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.