Common frog

The common frog (Rana temporaria), also known as the European common frog, European common brown frog, or European grass frog, is a semi-aquatic amphibian of the family Ranidae, found throughout much of Europe as far north as Scandinavia and as far east as the Urals, except for most of Iberia, southern Italy, and the southern Balkans. The farthest west it can be found is Ireland. It is also found in Asia, and eastward to Japan.

| Common frog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Ranidae |

| Genus: | Rana |

| Species: | R. temporaria |

| Binomial name | |

| Rana temporaria | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

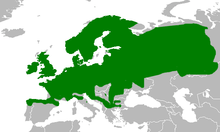

| Distribution of Rana temporaria in Europe | |

Common frogs metamorphose through three distinct developmental life stages — aquatic larva, terrestrial juvenile, and adult. They have corpulent bodies with a rounded snout, webbed feet and long hind legs adapted for swimming in water and hopping on land. Common frogs are often confused with the common toad Bufo bufo, but frogs can easily be distinguished as they have longer legs, hop, and have a moist skin, whereas toads crawl and have a dry 'warty' skin. The spawn of the two species also differs in that frogspawn is laid in clumps and toadspawn is laid in long strings.

Description

The adult common frog has a body length of 6 to 9 centimetres (2.4 to 3.5 in)[2] its back and flanks varying in colour from olive green[3] to grey-brown, brown, olive brown, grey, yellowish and rufous.[4] However, it can lighten and darken its skin to match its surroundings.[3] Some individuals have more unusual colouration—both black and red individuals have been found in Scotland, and albino frogs have been found with yellow skin and red eyes.[3] During the mating season the male common frog tends to turn greyish-blue (see video below).[3] The average mass is 22.7 g (0.80 oz); the female is usually slightly larger than the male.[5]

The flanks, limbs and backs are covered with irregular dark blotches[3] and they usually sport a chevron-shaped spot on the back of their neck and a dark spot behind the eye.[4] Unlike other amphibians, common frogs generally lack a mid-dorsal band but, when they have one, it is comparatively faint.[4] In many countries moor frogs have a light dorsal band which easily distinguishes them from common frogs. The underbelly is white or yellow (occasionally more orange in females) and can be speckled with brown or orange.[3] The eyes are brown with transparent horizontal pupils, and they have transparent inner eyelids to protect the eyes while underwater, as well as a 'mask' which covers the eyes and eardrums.[3] Although the common frog has long hind legs compared to the common toad, they are shorter than those of the agile frog with which it shares some of its range. The longer hind legs and fainter colouration of the agile frog are the main features that distinguish the two species.

Males are distinguishable from females as they are smaller and have hard swellings, known as nuptial pads, on the first digits of the forelegs, used for gripping females during mating.[2][3] During the mating season males' throats often turn white, and their overall colour is generally light and greyish, whereas the female is browner, or even red.[4]

Distribution

Common frogs are found throughout much of Europe as far north as northern Scandinavia inside the Arctic Circle and as far east as the Urals, except for most of Iberia, southern Italy, and the southern Balkans. Other areas where the common frog has been introduced include the Isle of Lewis, Shetland, Orkney and the Faroe Islands. It is also found in Asia, and eastward to Japan.[3][6]

The common frog has long been thought to be an entirely introduced species in Ireland,[7] however, genetic analyses suggest that particular populations in the south west of Ireland are indeed indigenous to the country.[8] The authors propose that the Irish frog population is a mixed group that includes native frogs that survived the last glacial period in ice free refugia, natural post-glacial colonisers and recent artificial introductions from Western Europe.[8][9]

Habitat

Outside the breeding season, common frogs live a solitary life in damp places near ponds or marshes or in long grass.[10] They are normally active for much of the year, only hibernating in the coldest months.[4] In the most northern extremities of their range they may be trapped under ice for up to nine months of the year, but recent studies have shown that in these conditions they may be relatively active at temperatures close to freezing.[10] In the British Isles, common frogs typically hibernate from late October to January. They will re-emerge as early as February if conditions are favourable, and migrate to bodies of water such as garden ponds to spawn.[7] Where conditions are harsher, such as in the Alps, they emerge as late as early June. Common frogs hibernate in running waters, muddy burrows, or in layers of decaying leaves and mud at the bottom of ponds or lakes primarily with a current. The oxygen uptake through the skin suffices to sustain the needs of the cold and motionless frogs during hibernation.[3][4][11]

Reproduction

During the spring the frog's pituitary gland is stimulated by changes in external factors, such as rainfall, day length and temperature, to produce hormones which, in turn, stimulate the production of sex cells - eggs in the females and sperm in the male. The male's nuptial pad also swells and becomes more heavily pigmented.[12] Common frogs breed in shallow, still, fresh water such as ponds, with spawning commencing sometime between March and late June, but generally in April over the main part of their range.[4]

The adults congregate in the ponds, where the males compete for females. The courtship ritual involves noisy vocalisations (croaking) by large "choirs" of males. The females are attracted to the males that produce the loudest and longest calls and enter the water, where the males mill around and try to grasp them with their front legs — although they may grasp anything of a similar size, such as a piece of wood. The successful male climbs on the back of the female and grasps her under the forelegs with his nuptial pads, in a position known as amplexus, and kicks away any other males that try to grasp her.[12] He then stays attached in this position until she lays her eggs, which he fertilises by spraying sperm over them as they are released from the female's cloaca.[3] The courtship rituals are performed throughout the day and night but spawning typically takes place at night. The females lay between 1,000 and 2,000 eggs which float in large clusters near the surface of the water.[3][13] After mating the pairs separate, the females will leave the water and the males will try to find another mate. Within three or four days all the females will have laid their eggs and left the water and the males disperse.[12]

Development

In common with other amphibians the rate of development of the larvae is influenced by temperature, with eggs and tadpoles in ponds at higher temperatures developing faster than those at lower temperatures.[14] Newly hatched tadpoles are mainly herbivorous, feeding on algae, detritus, plants and some small invertebrates, but they become fully carnivorous once their back legs develop, feeding on small water animals or even other tadpoles when food is scarce.[4] Juvenile frogs feed on invertebrates both on land and in water but their feeding habits change significantly throughout their lives and older frogs will eat only on land.[3] Adult common frogs will feed on any invertebrate of a suitable size, catching their prey on their long, sticky tongues,[3] although they do not feed at all during the short breeding season.[3] Preferred foods include insects (especially flies),[4] snails, slugs and worms.[3]

Conservation status

Common frogs are susceptible to a number of diseases, including Ranavirus and the parasitic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis which has been implicated in extinctions of amphibian species around the world.[15] Loss of habitat and the effect of these diseases has caused the decline of populations across Europe in recent years.[15] The common frog is listed as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1]

Predators

Tadpoles are eaten by fish, beetles, dragonfly larvae and birds. Adult frogs have many predators including storks, birds of prey, crows, gulls, ducks, terns, herons, pine martens, stoats, weasels, polecats, badgers, otters and snakes.[16] Some frogs are killed, but rarely eaten, by domestic cats, and large numbers are killed on the roads by motor vehicles.[17]

References

- S. Kuzmin (2008). "Rana temporaria". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sterry, Paul (1997). Complete British Wildlife Photoguide. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-583-33638-8.

- "Common frog, grass frog". bbc.co.uk science and nature. BBC. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- Sergius L., Kuzmin (10 November 1999). "Rana temporia". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- Common frog, grass frog

- Rana temporaria have established themselves as a wild population in Nólsoy

- "The Common Frog - (Rana temporaria)". enfo.ie. ENFO. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- Teacher, A. G. F.; T. W. J. Garner; R. A. Nichols (21 January 2009). "European phylogeography of the common frog (Rana temporaria): routes of postglacial colonization into the British Isles, and evidence for an Irish glacial refugium". Heredity. 102 (5): 490–496. doi:10.1038/hdy.2008.133. ISSN 0018-067X. PMID 19156165.

- "Irish frogs may have survived Ice Age". Zoological Society of London. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009.

- Roots, Clive (2006). Hibernation. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. pp. 510, 511. ISBN 0-313-33544-3.

- Dunlop, David (26 February 2004). "Common Frog final" (PDF). Lancashire BAP. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- Anon. "Frog Reproduction". Frog-garden.com. Frog-garden.com. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- The Macdonald Encyclopedia of Amphibians and Reptiles - Rana temporaria 80

- Wells, Kentwood D. (9 November 2007). "3". The Ecology and Behavior of Amphibians (1 ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 125. ISBN 0226893340.

- Eccleston, Paul (28 July 2008). "Appeal for public help to track deadly frog disease". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Anon. "Common frog: rana temporaria" (PDF). All about... Scottish National Heritage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- RSPB Birds magazine Summer 2004, page 66

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rana temporaria. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Rana temporaria |