Leeds

Leeds is the largest city in the county of West Yorkshire in Northern England, approximately 170 miles (270 km) north of central London.[6] It has one of the most diverse economies of all the UK's main employment centres and has seen the fastest rate of private-sector jobs growth of any UK city. It also has the highest ratio of private to public sector jobs of all the UK's Core Cities, with 77% of its workforce working in the private sector. Leeds has the third-largest jobs total by local authority area, with 480,000 in employment and self-employment at the beginning of 2015.[5] Leeds is ranked as a High Sufficiency level city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[7] Leeds is the cultural, financial and commercial heart of the West Yorkshire Urban Area.[8][9][10] The city is served by five universities, has the UK's fourth-largest student population and the country's fourth-largest urban economy.[11]

Leeds | |

|---|---|

| City of Leeds | |

Clockwise from top left: Leeds Town Hall, Trinity Leeds, Bridgewater Place, Leeds Dock, First Direct Arena | |

| Motto(s): Pro rege et lege (Latin: "For king and the law") | |

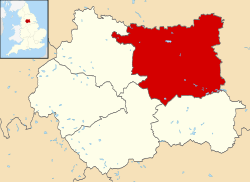

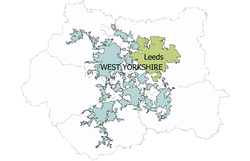

Shown within West Yorkshire | |

Leeds Location within England  Leeds Location within the United Kingdom  Leeds Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 53°47′59″N 1°32′57″W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| City region | Leeds |

| Ceremonial county | West Yorkshire |

| Metropolitan Borough | City of Leeds |

| Historic county | West Riding of Yorkshire |

| Borough charter | 1207 |

| Municipal charter | 1626 |

| City status | 1893 |

| Administrative HQ | Leeds Civic Hall, Millennium Square |

| Government | |

| • Type | Metropolitan borough |

| • Body | Leeds City Council |

| • Leadership | Leader and cabinet |

| • Executive | Labour |

| • Lord Mayor | Eileen Taylor |

| • Council Leader | Judith Blake |

| • Chief Executive | Tom Riordan |

| Area | |

| • City | 213.0 sq mi (551.7 km2) |

| • Urban | 188.3 sq mi (487.8 km2) |

| Area rank | 83rd |

| Highest elevation | 1,115 ft (340 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 33 ft (10 m) |

| Population (mid-2019 est.) | |

| • City | 793,139 |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 3,700/sq mi (1,430/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,901,934 (4th) |

| • Urban density | 9,440/sq mi (3,645/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,638,127 (4th) |

| • Ethnicity (2011 census)[3] | 85% White 5.7% Asian or Asian British 3.5% Black or Black British 2.7% Mixed Race 3.1% Other |

| Demonym(s) | Loiner, Leodensian |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Dialling codes | 0113 (Leeds) 01924 (Wakefield) 01937 (Wetherby) 01943 (Guiseley) 01977 (Pontefract) |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-LDS |

| GSS code | E08000035 |

| NUTS 3 code | UKE42 |

| ONS code | 00DA |

| OS grid reference | SE296338 |

| Motorways | M1 M62 M621 A1(M) A58(M) A64(M) |

| Major railway stations | Leeds (A) |

| International airports | Leeds Bradford (LBA) |

| GDP | US$82.98 billion[4][5] |

| – Per capita | US$33,355[4] |

| GVA (2015) | £21.3bn (4th) |

| – Per capita | £27,466 (4th) |

| Councillors | 99 |

| MPs | List of MPs

|

| Website | www.leeds.gov.uk |

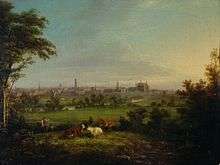

Leeds was a small manorial borough in the 13th century, becoming a major centre for the production and trading of wool in the 17th and 18th centuries, then a major mill town during the Industrial Revolution; wool was still the dominant industry, but flax, engineering, iron foundries, printing, and other industries were also important.[12] From being a market town in the valley of the River Aire in the 16th century, Leeds expanded and absorbed the surrounding villages to become a populous urban centre by the mid-20th century. It now lies within the West Yorkshire Urban Area, the UK's fourth-most populous urban area, with a reported population of 2.6 million in 2013.[13]

Today, Leeds has become the largest legal and financial centre outside London[5][14] with the financial and insurance services industry worth £13 billion to the city's economy. The finance and business service sector account for 38% of total output[5][15][16] with more than 30 national and international banks located in the city, including an office of the Bank of England.[14] Leeds is also the UK's third-largest manufacturing centre with around 1,800 firms and 39,000 employees; Leeds manufacturing firms account for 8.8% of total employment in the city and is worth over £7 billion to the local economy.[15] The largest sub-sectors are engineering, printing and publishing, food and drink, chemicals and medical technology.[17] Other key sectors include retail, leisure and the visitor economy, construction, and the creative and digital industries. The city saw several firsts, including the oldest-surviving film in existence, Roundhay Garden Scene (1888), and the 1767 invention of soda water.[18][19]

Public transport, rail and road communications networks in the region are focused on Leeds; the second phase of High Speed 2 will connect it to London via East Midlands Hub and Sheffield. Leeds currently has the third busiest railway station[20] and the tenth busiest airport outside London.[21] Leeds has a less extensive public transport coverage than other UK cities of comparable size, and is the largest city in Europe without any form of light rail or underground system. [22]

History

Toponymy

The name derives from the old Brythonic word Ladenses meaning "people of the fast-flowing river", in reference to the River Aire that flows through the city.[23] This name originally referred to the forested area covering most of the Brythonic kingdom of Elmet, which existed during the 5th century into the early 7th century.[24]

Bede states in the fourteenth chapter of his Ecclesiastical History, in a discussion of an altar surviving from a church erected by Edwin of Northumbria, that it is located in ...regione quae vocatur Loidis (Latin, "the region which is called Loidis"). An inhabitant of Leeds is locally known as a Loiner, a word of uncertain origin.[25] The term Leodensian is also used, from the city's Latin name.

The name has also been explained as a derivative of Welsh lloed, meaning simply "a place".[26]

Economic development

Leeds developed as a market town in the Middle Ages as part of the local agricultural economy.

Before the Industrial Revolution, it became a co-ordination centre for the manufacture of woollen cloth, and white broadcloth was traded at its White Cloth Hall.[27]

Leeds handled one sixth of England's export trade in 1770.[28] Growth, initially in textiles, was accelerated by the building of the Aire and Calder Navigation in 1699 and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in 1816.[29] In the late Georgian era, William Lupton was one of a number of central Leeds landowners with a mesne lord title, some of whom, like him, were textile manufacturers. At the time of his death in 1828, Lupton occupied the enclosed fields of the manor of Leeds, his estate including a mill, reservoir, substantial house and outbuildings.[30][31]

The railway network constructed around Leeds, starting with the Leeds and Selby Railway in 1834, provided improved communications with national markets and, significantly for its development, an east–west connection with Manchester and the ports of Liverpool and Hull giving improved access to international markets.[32] Alongside technological advances and industrial expansion, Leeds retained an interest in trading in agricultural commodities, with the Corn Exchange opening in 1864.

Marshall's Mill was one of the first of many factories constructed in Leeds from around 1790 when the most significant were woollen finishing and flax mills.[33] Manufacturing diversified by 1914 to printing, engineering, chemicals and clothing manufacture.[34] Decline in manufacturing during the 1930s was temporarily reversed by a switch to producing military uniforms and munitions during the Second World War. However, by the 1970s, the clothing industry was in irreversible decline, facing cheap foreign competition.[35] The contemporary economy has been shaped by Leeds City Council's vision of building a '24-hour European city' and 'capital of the north'.[36] The city has developed from the decay of the post-industrial era to become a telephone banking centre, connected to the electronic infrastructure of the modern global economy.[36] There has been growth in the corporate and legal sectors,[37] and increased local affluence has led to an expanding retail sector, including the luxury goods market.[38]

Leeds City Region Enterprise Zone was launched in April 2012 to promote development in four sites along the A63 East Leeds Link Road.[39]

Local government

| 1881 | 160,109 |

|---|---|

| 1891 | 177,523 |

| 1901 | 177,920 |

| 1911 | 259,394 |

| 1921 | 269,665 |

| 1931 | 482,809 |

| 1941 | war* |

| 1951 | 505,219 |

| 1961 | 510,676 |

| *no census was held due to war | |

| source: UK census[40] | |

Leeds was a manor and township in the large ancient parish of Leeds St Peter, in the Skyrack wapentake of the West Riding of Yorkshire.[41] The Borough of Leeds was created in 1207, when Maurice Paynel, lord of the manor, granted a charter to a small area of the manor, close to the river crossing, in what is now the city centre. Four centuries later, the inhabitants petitioned Charles I for a charter of incorporation, which was granted in 1626. The new charter incorporated the entire parish, including all eleven townships, as the Borough of Leeds and withdrew the earlier charter. Improvement commissioners were set up in 1755 for paving, lighting, and cleansing of the main streets, including Briggate and further powers were added in 1790 to improve the water supply.[42]

The borough corporation was reformed under the provisions of Municipal Corporations Act 1835. Leeds Borough Police force was formed in 1836, and Leeds Town Hall was completed by the corporation in 1858. In 1866, Leeds and each of the other townships in the borough became civil parishes. The borough became a county borough in 1889, giving it independence from the newly formed West Riding County Council and it gained city status in 1893. In 1904 the Leeds parish absorbed Beeston, Chapel Allerton, Farnley, Headingley cum Burley and Potternewton from within the borough. In the twentieth century the county borough initiated a series of significant territorial expansions, growing from 21,593 acres (87.38 km2) in 1911 to 40,612 acres (164.35 km2) in 1961.[43] In 1912 the parish and county borough of Leeds absorbed Leeds Rural District, consisting of the parishes of Roundhay and Seacroft; and Shadwell, which had been part of Wetherby Rural District. On 1 April 1925, the parish of Leeds was expanded to cover the whole borough.[41]

The county borough was abolished on 1 April 1974, and its former area was combined with that of the municipal boroughs of Morley and Pudsey; the urban districts of Aireborough, Horsforth, Otley, Garforth and Rothwell; and parts of the rural districts of Tadcaster, Wetherby, and Wharfedale.[44] This area formed a metropolitan district in the county of West Yorkshire. It gained both borough and city status and is known as the City of Leeds. Initially, local government services were provided by Leeds City Council and West Yorkshire County Council. When the county council was abolished in 1986, the city council absorbed its functions, and some powers passed to organisations such as the West Yorkshire Passenger Transport Authority. From 1988 two run-down and derelict areas close to the city centre were designated for regeneration and became the responsibility of Leeds Development Corporation, outside the planning remit of the city council.[45] Planning powers were restored to the local authority in 1995 when the development corporation was wound up.

Suburban growth

In 1801, 42% of the population of Leeds lived outside the township, in the wider borough. Cholera outbreaks in 1832 and 1849 caused the authorities to address the problems of drainage, sanitation, and water supply. Water was pumped from the River Wharfe, but by 1860 it was too heavily polluted to be usable. Following the Leeds Waterworks Act of 1867 three reservoirs were built at Lindley Wood, Swinsty, and Fewston in the Washburn Valley north of Leeds.[46]

Residential growth occurred in Holbeck and Hunslet from 1801 to 1851, but, as these townships became industrialised new areas were favoured for middle class housing.[47] Land south of the river was developed primarily for industry and secondarily for back-to-back workers' dwellings. The Leeds Improvement Act 1866 sought to improve the quality of working class housing by restricting the number of homes that could be built in a single terrace.[48]

Holbeck and Leeds formed a continuous built-up area by 1858, with Hunslet nearly meeting them.[49] In the latter half of the nineteenth century, population growth in Hunslet, Armley, and Wortley outstripped that of Leeds. When pollution became a problem, the wealthier residents left the industrial conurbation to live in Headingley, Potternewton and Chapel Allerton which led to a 50% increase in the population of Headingley and Burley from 1851 to 1861. The middle-class flight from the industrial areas led to development beyond the borough at Roundhay and Adel.[49] The introduction of the electric tramway led to intensification of development in Headingley and Potternewton and expansion outside the borough into Roundhay.[50]

Two private gas supply companies were taken over by the corporation in 1870, and the municipal supply provided street lighting and cheaper gas to homes. From the early 1880s, the Yorkshire House-to-House Electricity Company supplied electricity to Leeds until it was purchased by Leeds Corporation and became a municipal supply.[51]

Slum clearance and rebuilding began in Leeds during the interwar period when over 18,000 houses were built by the council on 24 estates in Cross Gates, Middleton, Gipton, Belle Isle and Halton Moor. The slums of Quarry Hill were replaced by the innovative Quarry Hill flats, which were demolished in 1975. Another 36,000 houses were built by private sector builders, creating suburbs in Gledhow, Moortown, Alwoodley, Roundhay, Colton, Whitkirk, Oakwood, Weetwood, and Adel. After 1949 a further 30,000 sub-standard houses were demolished by the council and replaced by 151 medium-rise and high-rise blocks of council flats in estates at Seacroft, Armley Heights, Tinshill, and Brackenwood.[52]

Leeds has seen great expenditure on regenerating the city, attracting in investments and flagship projects,[53] as found in Leeds city centre. Many developments boasting luxurious penthouse apartments have been built close to the city centre.

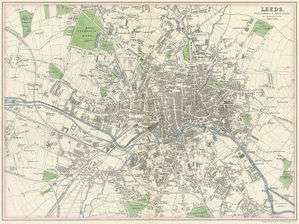

Geography

Leeds is located 169 miles (272 km) north-northwest of London,[54] on the valley of the River Aire in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. The city centre lies in a narrow section of the Aire Valley at about 206 feet (63 m) above sea level; while the district ranges from 1,115 feet (340 m) in the far west on the slopes of Ilkley Moor to about 33 feet (10 m) where the rivers Aire and Wharfe cross the eastern boundary. There are also significant variations in elevation within the city itself. For example, land rises to 198 m (650 ft) in Cookridge, just 6 miles (9.7 km) from the city centre. The centre of Leeds is part of a continuously built-up area extending to Pudsey, Bramley, Horsforth, Alwoodley, Seacroft, Middleton and Morley.[55]

Leeds has the second-highest population of any local authority district in the UK (after Birmingham), and the second-greatest area of any English metropolitan district (after Doncaster), extending 15 miles (24 km) from east to west, and 13 miles (21 km) from north to south. The northern boundary follows the River Wharfe for several miles (several kilometres), but it crosses the river to include the part of Otley which lies north of the river.

The city centre is less than twenty miles (32 km)) from the Yorkshire Dales National Park,[56] which has some of the most spectacular scenery and countryside in the UK.[57] Inner and southern areas of Leeds lie on a layer of coal measure sandstones forming the Yorkshire Coalfield. To the north parts are built on older sandstone and gritstones and to the east it extends into the magnesian limestone belt.[33][58][59] The land use in the central areas of Leeds is overwhelmingly urban.[55]

Attempts to define the exact geographic meaning of Leeds lead to a variety of concepts of its extent, varying by context include the area of the city centre, the urban sprawl, the administrative boundaries, and the functional region.[60]

Leeds is much more a generalised concept place name in inverted commas, it is the city, but it is also the commuter villages and the region as well.

— Brian Thompson, A History of Modern Leeds[60]

Leeds city centre is contained within the Leeds Inner Ring Road, formed from parts of the A58 road, A61 road, A64 road, A643 road and the M621 motorway. Briggate, the principal north–south shopping street, is pedestrianised and Queen Victoria Street, a part of the Victoria Quarter, is enclosed under a glass roof. Millennium Square is a significant urban focal point. The Leeds postcode area covers most of the City of Leeds[61] and is almost entirely made up of the Leeds post town.[62] Otley, Wetherby, Tadcaster, Pudsey and Ilkley are separate post towns within the postcode area.[62] Aside from the built up area of Leeds itself, there are a number of suburbs and exurbs within the district.

Climate

Leeds has a climate that is oceanic (Köppen: Cfb), and influenced by the Pennines. Summers are usually mild, with moderate rainfall, while winters are chilly, cloudy with occasional snow and frost. The nearest official weather recording station is at Bingley, some twenty kilometres away at a higher altitude.[63]

July is the warmest month, with a mean temperature of 16 °C (61 °F), while the coldest month is January, with a mean temperature of 3 °C (37 °F). Temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) and below −10 °C (14 °F) are not very common but can happen occasionally. Temperatures at Leeds Bradford Airport fell to −12.6 °C (9.3 °F) in December 2010[64] and reached 31.8 °C (89 °F) at Leeds city centre in August 2003.[65] The record temperature for Leeds is 34.4 °C (94 °F) during the early August 1990 heatwave. It is possible this was exceeded during the heatwave of July 2019 where many other areas broke their all time records. However Leeds weather centre closed in the 2000s.

As is typical for many sprawling cities in areas of varying topography, temperatures can change depending on location. Average July and August daytime highs exceed 22 °C (72 °F) (a value comparable to South East England) in a small area just to the south east of the city centre,[66][67] where the elevation declines to under 20 metres (66 feet). This is 2 °C (3.6 °F) milder than the typical summer temperature at Leeds Bradford airport weather station (shown in the chart below), at an elevation of 208 metres (682 feet).

Situated on the eastern side of the Pennines, Leeds is among the driest cities in the United Kingdom, with an annual rainfall of 660 mm (25.98 in).

Though extreme weather in Leeds is relatively rare, thunderstorms, blizzards, gale-force winds and even tornadoes have struck the city. The last reported tornado occurred on 14 September 2006, causing trees to uproot and signal failures at Leeds City railway station.[68]

| Climate data for Leeds Bradford | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15 (59) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

12.6 (54.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4.9 (40.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61 (2.4) |

45 (1.8) |

52 (2.0) |

48 (1.9) |

54 (2.1) |

54 (2.1) |

51 (2.0) |

65 (2.6) |

57 (2.2) |

55 (2.2) |

57 (2.2) |

61 (2.4) |

660 (25.9) |

| Average precipitation days | 17.5 | 14.2 | 14.8 | 13.5 | 13.7 | 12.2 | 11.7 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 15.1 | 16.5 | 17.0 | 172.3 |

| Source: [69][70] | |||||||||||||

Green belt

Leeds is within a green belt region that extends into the wider surrounding counties and is in place to reduce urban sprawl, prevent the settlements in the West Yorkshire conurbation from further convergence, protect the identity of outlying communities, encourage brownfield reuse, and preserve nearby countryside. This is achieved by restricting inappropriate development within the designated areas, and imposing stricter conditions on permitted building.[71]

Over 60% of the Leeds district is green belt land and it surrounds the settlement, preventing further sprawl towards nearby communities. Larger outlying towns and villages are exempt from the green belt area. However, smaller villages, hamlets and rural areas are 'washed over' by the designation. The green belt was first adopted in 1960,[71] and the size in the borough in 2017 amounted to some 33,970 hectares (339.7 km2; 131.2 sq mi).[72]

A subsidiary aim of the green belt is to encourage recreation and leisure interests,[71] with rural landscape features, greenfield areas and facilities including Temple Newsam Park and House with golf course, Rothwell Country Park, Middleton Park, Kirkstall Abbey ruins and surrounding park, Bedquilts recreation grounds, Waterloo lake, Roundhay castle and park, and Morwick, Cobble and Elmete Halls.

Demographics

Urban subdivision

Leeds urban subdivision shown within the West Yorkshire urban area the West Yorkshire urban area | ||||

| 2001 UK Census | Leeds USD | Leeds district | West Yorks UA | England (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 443,247 | 715,402 | 1,499,465 | 53,012,456 |

| White | 88.4% | 91.9% | 85.5% | 85.4% |

| Asian | 6.4% | 4.5% | 11.2% | 7.8% |

| Black | 2.2% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 3.5% |

| Source: Office for National Statistics[73][74] | ||||

At the time of the United Kingdom Census 2001, the Leeds urban subdivision occupied an area of 109 square kilometres (42 sq mi) and had a population of 443,247; making it the fourth-most populous urban subdivision within England and the fifth largest within the United Kingdom. The population density was 4,066 inhabitants per square kilometre (10,530/sq mi), slightly higher than the rest of the West Yorkshire Urban Area. It accounts for 20% of the area and 62% of the population of the City of Leeds. The population of the urban subdivision had a 100 to 93.1 female–male ratio.[75] Of those over 16 years old, 39.4% were single (never married) and 35.4% married for the first time.[76] The urban subdivision's 188,890 households included 35% one-person, 27.9% married couples living together, 8.8% were co-habiting couples, and 5.7% single parents with their children. Leeds is the largest component of the West Yorkshire Urban Area[55] and is counted by Eurostat as part of the Leeds-Bradford larger urban zone. The Leeds travel to work area in 2001 included all of the City of Leeds, a northern strip of the City of Bradford, the eastern part of Kirklees, and a section of southern North Yorkshire; it occupies 751 square kilometres (290 sq mi).

In 2011, the Leeds USD had a population of 474,632 and had an area of 112 square kilometres (43 sq mi) with a population density of 4,238 inhabitants per square kilometre (10,980/sq mi).[77] It is bounded by, and physically attached to, the other towns of Garforth to the east, Morley to the southwest and Pudsey to the west, all being within the wider borough. 63% of the borough's population of 751,485 live in the USD, while it takes up only 21% of its area.

| Leeds compared | Leeds USD | Leeds City |

|---|---|---|

| White British | 73.9% | 81.1% |

| Asian | 10.7% | 7.7% |

| Black | 5.2% | 3.5% |

In 2011, the Leeds USD (Urban Subdivision) had a total 'White' population of 79.1%[77] with this percentage including people from places such as mainland Europe and Ireland. The USD is what is commonly regarded as being Leeds itself, however it is the wider borough that has been given city status.

Metropolitan district

At the time of the 2011 UK Census, the district had a total population of 751,500, representing a 5% growth since the previous census ten years earlier.[80] According to the 2001 UK Census, there were 301,614 households in Leeds; 33.3% were married couples living together, 31.6% were single-person households, 9.0% were co-habiting couples and 9.8% were single parents, following a similar trend to the rest of England.[81] The population density was 1,967/km2 (5,090/sq mi)[81] and for every 100 females, there were 93.5 males.

Leeds is a diverse city with over 75 ethnic groups, and with ethnic minorities representing just under 11.6% of the total population.[80] According to figures from the 2011 UK Census, 85.0% of the population was White (81.1% White British, 0.9% White Irish, 0.1% Gypsy or Irish Traveller, 2.9% Other White), 2.7% of mixed race (1.2% White and Black Caribbean, 0.3% White and Black African, 0.7% White and Asian, 0.5% Other Mixed), 7.7% Asian (2.1% Indian, 3.0% Pakistani, 0.6% Bangladeshi, 0.8% Chinese, 1.2% Other Asian), 3.5% Black (2.0% African, 0.9% Caribbean, 0.6% Other Black), 0.5% Arab and 0.6% of other ethnic heritage. Leeds has seen many new different countries of birth as of the UK Census including Zimbabwe, Iran, India and Nigeria all included in the top ten countries of birth in the city. Large Pakistani communities can be seen in wards such as Gipton and Harehills. Chapel Allerton is known for having a large Caribbean community.[82]

The majority of people in Leeds identify themselves as Christian.[83] The proportion of Muslims (3.0% of the population) is average for the country.[83] Leeds has the third-largest community of Jews in the United Kingdom, after those of London and Manchester. The areas of Alwoodley and Moortown contain sizeable Jewish communities.[84] 16.8% of Leeds residents in the 2001 census declared themselves as having "No Religion", which is broadly in line with the figure for the whole of the UK (also 8.1% "religion not stated"). The crime rate in Leeds is well above the national average, like many other English major cities.[85][86] In July 2006, the think tank Reform calculated rates of crime for different offences and has related this to populations of major urban areas (defined as towns over 100,000 population). Leeds was 11th in this rating (excluding London boroughs, 23rd including London boroughs).[87] Total recorded crime in Leeds fell by 45% between 2002/03 and 2011/12.[80]

The table below details the population of the current area of the district since 1801, including the percentage change since the last available census data.

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 94,421 | 108,459 | 137,476 | 183,015 | 222,189 | 249,992 | 311,197 | 372,402 | 433,607 | 503,493 | 552,479 | 606,250 | 625,854 | 646,119 | 668,667 | 692,003 | 715,260 | 739,401 | 696,732 | 716,760 | 715,404 | 751,500 |

| % change | – | +14.87 | +26.75 | +33.13 | +21.40 | +12.51 | +24.48 | +19.67 | +16.44 | +16.12 | +9.73 | +9.73 | +3.23 | +3.24 | +3.49 | +3.49 | +3.36 | +3.38 | −5.77 | +2.87 | −0.19 | +5.05 |

| Source: Vision of Britain[88] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Governance

The City of Leeds is the local government district covering Leeds, and the local authority is Leeds City Council. The council is composed of 99 councillors, three for each of the district's wards. Elections are held three years out of four, on the first Thursday of May. One third of the councillors are elected, for a four-year term, in each election. The council is currently controlled by Labour. West Yorkshire does not have a county council, so Leeds City Council is the primary provider of local government services for the city. The district is in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England.

Most of the district is an unparished area. In the unparished area, there is no lower tier of government. Outside the unparished area, there are 31 civil parishes, represented by parish councils. These are the lowest tier of local government[89] and absorb some limited functions from Leeds City Council in their areas.

The district is represented by eight MPs, for the constituencies of Elmet and Rothwell (Alec Shelbrooke, Conservative); Leeds Central (Hilary Benn, Labour); Leeds East (Richard Burgon, Labour); Leeds North East (Fabian Hamilton, Labour); Leeds North West (Alex Sobel, Labour); Leeds West (Rachel Reeves, Labour); Morley and Outwood (constituency shared with City of Wakefield) (Andrea Jenkyns, Conservative); and Pudsey (Stuart Andrew, Conservative).

In addition to other national governmental offices, the city is home to a large Department for Work and Pensions office building located in Quarry Hill, notable for its imposing design.

Economy

Leeds has the most diverse economy of all the UK's main employment centres and has seen the fastest rate of private sector jobs growth of any UK city and has the highest ratio of public to private sector jobs of all the UK's Core Cities. The city has the third-largest jobs total by local authority area with 480,000 in employment and self-employment at the beginning of 2015.[90] 24.7% were in public administration, education and health, 23.9% were in banking, finance and insurance and 21.4% were in distribution, hotels and restaurants. It is in the banking, finance and insurance sectors that Leeds differs most from the financial structure of the region and the nation.[91] In 2011, the financial and services industry in Leeds was worth £2.1 billion, the fifth-largest in the UK, behind London, Edinburgh, Manchester and Birmingham.[16] Tertiary industries such as retail, call centres, offices and media have contributed to a high rate of economic growth. The city also hosts the only subsidiary office of the Bank of England in the UK. In 2012 GVA for the city was recorded at £18.8 billion,[92] with the entire Leeds City Region generating a £56 billion economy.[5]

It is the largest centre outside London for financial and business services. Over the next ten years, the economy is forecast to grow by 25% with financial and business services set to generate over half of GVA growth over that period with Finance and business services accounting for 38% of total output. Other key sectors include retail, leisure and the visitor economy, construction, manufacturing and the creative and digital industries.[5]

Leeds has over 30 national and international banks, many of whose northern or regional offices are based in the city. It is the headquarters for First Direct and Yorkshire Bank, and has large Barclays, HSBC, Santander, Lloyds Banking Group and RBS Group operations.[93]

The city is also an important centre for equity, venture and risk finance. Founded in Leeds, the venture capital provider, YFM Equity Partners, is now the UK's largest provider of risk capital to small and medium-sized enterprises.[93]

Other major companies based in the city include William Hill, International Personal Finance, Asda, Leeds Building Society and Northern Foods. Capita Group, KPMG, Direct Line, Aviva, Yorkshire Building Society, BT Group, Telefónica Europe (otherwise known as O2) and TD Waterhouse all also have a considerable presence in the city.[93]

There are around 150 law firms operating in Leeds, employing over 6,700 people. According to The UK Legal 500, "Leeds has a sophisticated and highly competitive legal market, second only to London."[94]

Specialist legal expertise to be found in Leeds includes corporate finance, corporate restructuring and insolvency, global project financing, trade and investment, commercial litigation, competition, construction, Private Finance Initiatives and Public Private Partnerships, tax, derivatives, IT, employment, pensions, intellectual property, sport and entertainment.[94]

The establishment of an Administrative Court in Leeds in April 2009 reinforced Leeds's position as one of the UK's key legal centres. The court previously sat only in London.[94]

Leeds is the UK's third-largest manufacturing centre and 50% of the UK's manufacturing base is within a two-hour drive of Leeds. With around 1,800 firms and 39,000 employees, Leeds manufacturing firms account for 8.8% of total employment in the city. The largest sub-sectors are engineering, printing and publishing, food and drink, chemicals and medical technology.[17]

There is also an established creative industry in the city, particularly in the digital gaming sector. A number of large developers have studios in and around the city, including Activision, developers of the mobile versions of the Call of Duty series, and Rockstar Leeds, developers of the Grand Theft Auto series. In 2009 Leeds was the first city outside London to host the Eurogamer Expo.

Office developments, also traditionally located in the inner area, have expanded south of the River Aire and total 11,000,000 square feet (1,000,000 m2) of space.[95] In the period from 1999 to 2008 £2.5bn of property development was undertaken in central Leeds; of which £711m has been offices, £265m retail, £389m leisure and £794m housing. Manufacturing and distribution uses accounts for £26m of new property development in the period. There are 130,100 jobs in the city centre, accounting for 31% of all jobs in the wider district. In 2007, 47,500 jobs were in finance and business, 42,300 in public services, and 19,500 in retail and distribution. 43% of finance sector jobs in the district are contained in Leeds city centre and 44% of those employed in the city centre live more than nine kilometres (5.6 miles) away.[95]

Tourism is important to the Leeds economy, in 2009 Leeds was the eighth-most visited city in England by UK visitors.[96] and the 13th-most visited city by overseas visitors.[97] Research by VisitEngland reported that the day visitor market to Leeds attracts 24.9 million people each year, worth over £654 million to the local economy.[98] In the 2017 Condé Nast Traveler survey of readers, Leeds rated 6th among The 15 Best Cities in the UK for visitors.[99]

In 2016, Leeds received 27.29 million leisure tourist visits generating over £1.6bn for the city, according to data from a STEAM survey. That was a 15.9% increase in revenue over 2015. A 9.7% increase in visits had been recorded since 2013.[100] The industry supported over 19,000 full-time equivalent jobs in 2016.[101]

In January 2011, Leeds was named as one of five "cities to watch" in a report published by Centre for Cities.[102] The report shows that the average resident in Leeds earns £471 per week,[103] seventeenth nationally and 30.9% of Leeds residents had NVQ4+ high-level qualifications,[104] fifteenth nationally. Employment in Leeds was 68.8% in the period June 2012 to June 2013, which was lower than the national average, whilst unemployment was higher than the national average at 9.6% over the same time period.[105] It also shows that Leeds will be the least affected major city by welfare cuts in 2014/2015, with welfare cuts of £125 per capita predicted, compared to £192 in Liverpool and £175 in Glasgow.[106] Leeds is overall less deprived than other large UK cities and average income is above regional averages.[80]

Public sector

In Leeds, 108,000 people work in the public sector—24% of the workforce. The largest employers are Leeds City Council, with 33,000 staff, and the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, with 14,000 staff.[107]

Leeds has become a hub of public-sector health bodies. The Department of Health, NHS England, the Care Quality Commission, NHS Digital, and Public Health England all have large offices in Leeds. Europe's largest teaching hospital is also based in Leeds, and is home to the Yorkshire Cancer Centre, the largest of its kind in Europe.[108]

Key government departments and organisations in Leeds include the Department for Work and Pensions, with over 3,000 staff, the Department of Health, with over 800 staff, HM Revenue and Customs with over 1,200 staff and the British Library with 1,100 staff.[107]

Shopping

_004.jpg)

The extensive retail area of Leeds is identified as the principal regional shopping centre for the whole of the Yorkshire and the Humber region with a catchment of 5.5 million people offering a spend of £1.93 billion annually.[109] There are a number of indoor shopping centres in the centre of the city, including the Merrion Centre, St John's Centre, The Core, the Victoria Quarter, The Light, the Corn Exchange, Trinity Leeds, and Victoria Gate.[110] In total there are well over 1,000 retail stores, with a combined floorspace of 3,660,000 square feet (340,000 m2).[95] in Leeds City Centre.

The city centre has a large pedestrian zone. Briggate is the main shopping street where one can find many well-known British High Street stores, including Marks & Spencer, House of Fraser, Debenhams, Topshop, Costa Coffee and Harvey Nichols. Many companies have several stores within Central Leeds and the wider city. The Victoria Quarter is notable for its high-end luxury retailers and impressive architecture. 70 stores such as Louis Vuitton, Vivienne Westwood, Paul Smith, Diesel and anchor Harvey Nichols are contained within two iron-wrought Victorian arcades, and a new arcade formed by arcading Queen Victoria Street with the largest expanse of stained glass in Britain.[111][112]

In the Churwell area of Leeds is the White Rose Shopping Centre. Opening in 1997, the centre has over 100 high street stores anchored by Debenhams, Marks & Spencer, Primark and Sainsbury's. Some stores have their only Leeds presence here and do not trade in Central Leeds, such as the Disney Store and Build-A-Bear workshop. Although the centre is below the average typical size for out of town shopping malls like the Trafford Centre or Meadowhall in nearby Yorkshire city Sheffield, it remains popular with national and international chains. Of the 40,000 people who work in retailing in Leeds 75% work in places which are not located in the city centre. There are additional shopping centres located in the many villages that became part of the county borough and in the towns that were incorporated in the City of Leeds in 1974.[113]

On 21 March 2013, a large shopping and leisure complex called Trinity Leeds opened in the city centre. The modern and interactive retail space covers the old Burton Arcades and the former Leeds Shopping Plaza with its main entrance from Briggate.[114]

On 20 October 2016, the newest shopping destination called Victoria Gate opened its doors to the public. The new shopping mall houses a flagship John Lewis store, the largest outside London. Seventy-five per cent of the stores that opened in Victoria Gate were new to Leeds with many of those stores being the first outside of London.[115]

Landmarks

_(4824877432).jpg)

Leeds displays a variety of natural and built landmarks. Natural landmarks include such diverse sites as the gritstone outcrop of Otley Chevin and the Fairburn Ings RSPB reserve. The city's parks at Roundhay and Temple Newsam have long been owned and maintained by the council for the benefit of ratepayers and among the open spaces in the centre of Leeds are Millennium Square, City Square, Park Square and Victoria Gardens. This last is the site of the central city war memorial: there are 42 other war memorials in the suburbs, towns and villages in the district.[116] On 14 June 2020, thousands of people gathered in Millennium Square to show support for the Black Lives Matter movement with peaceful protest.[117]

The built environment embraces edifices of civic pride like Morley Town Hall and the trio of buildings in Leeds, Leeds Town Hall, Corn Exchange and Leeds City Museum by the architect Cuthbert Brodrick. The two white buildings on the Leeds skyline are the Parkinson building of Leeds University and the Civic Hall, with golden owls adorning the tops of the latter's twin spires.[118]

Armley Mills, Tower Works, with its campanile-inspired towers, and the Egyptian-style Temple Works hark back to the city's industrial past, while the site and ruins of Kirkstall Abbey display the beauty and grandeur of Cistercian architecture. Notable churches are Leeds Minster (formerly Leeds Parish Church), St George's Church and Leeds Cathedral, in the city centre, and the Church of St John the Baptist, Adel and Bardsey Parish Church in quieter locations. Notable non-conformist chapels include the Salem Chapel, dating back to 1791 and notably the birthplace of Leeds United Football Club in 1919.[119][120]

Leeds is one of only a few UK cities outside of London to have a significant number of high-rise buildings, the 112-metre (367 ft) tower of Bridgewater Place, also known as The Dalek, is part of a major office and residential development and the region's tallest building; it can be seen for miles (kilometres) around.[121] Bridgewater Place has been the subject of debate as its erection in 2007 caused significant wind tunnel effects, channeling strong wind currents across Victoria Road. There have been numerous injuries attributed to the inadequate architecture of this building[122] and Water Lane is frequently closed when high winds are expected. In 2017 Leeds City Council undertook construction work in an attempt to deflect the wind from street level and the building owners of Bridgewater Place agreed to pay to cover the public money being spent.[123][124] Among other Skyscrapers the 37-storey Sky Plaza to the north of the city centre stands on higher ground so that its 106 metres (348 ft) is higher than Bridgewater Place.

Elland Road (football) and Headingley Stadium (cricket and rugby) are well known to sports enthusiasts and the White Rose Centre is a well-known retail outlet.

Transport

Leeds' transport system is dominated by cars and it is currently the 9th most congested UK city, with congestion costing £1,057 per driver.[125]

There have long been plans for a public transport network in Leeds, yet as of 2020, none have come to fruition. In the 1940s, there were plans to build an extensive underground system, however these were scuppered by the Second World War.[126] There were plans for a Leeds Supertram in the 1990s and £500 million in funding was to be provided; however, due to spiralling costs, the plans were cancelled by the Transport Minister Alistair Darling in 2005, even though £40 million had already been spent on the project. Hopes were renewed with the proposal for a £250 million New Generation Transport Trolleybus service in 2007; however, after a long wait and millions of pounds spent on inquiries, the plans were cancelled in May 2016 citing little value for money.[127]

In 2019 June 2019, as part of his bid to become Prime Minister, Boris Johnson stated that it was "madness" that Leeds did not have a metro system.[128] In December 2019, during his first Queen's Speech, Johnson promised to "remedy the scandal that Leeds is the largest city in Western Europe without light rail or a metro".[129]

Neville Street, near Leeds railway station, has been measured as the most polluted outside London.[130] As part of plans to tackle inner city air pollution, Leeds will introduce a Clean Air Zone in 2020, which will charge the most polluting buses, coaches and HGVs £50 a day to enter the city; taxis and private hire vehicles, which are not clean enough, will be charged £12.50 a day. The proposals came after the government ordered the council to come up with ways to lower the air pollution in the city, which causes around 29,000 premature deaths in the UK.[131]

Road

Leeds is the starting point of the A62, A63, A64, A65 and A660 roads, and is also situated on the A58 and A61. The M1 and M62 intersect to its south and the A1(M) passes to the east. Leeds is one of the principal hubs of the northern motorway network. Additionally, there is an urban motorway network; the radial M621 takes traffic into central Leeds from the M62 and M1. There is an Inner Ring Road with part motorway status and an Outer Ring Road. Part of the city centre[132] is pedestrianised, and is encircled by the clockwise-only Loop Road.

Buses

.jpg)

Public transport in the Leeds area is coordinated and developed by West Yorkshire Metro,[133] with service information provided by Leeds City Council[134] and West Yorkshire Metro. The primary means of public transport in Leeds are the bus services. The main provider is First Leeds and Arriva Yorkshire serves routes to the south of the city. Leeds City bus station is at Dyer Street and is used by bus services to towns and cities in Yorkshire, plus a small number of local services. Adjacent to it is the coach station for National Express coach services. Buses out of the city are mainly provided by First Leeds and Arriva Yorkshire. Harrogate Bus Company provides a service to Harrogate and Ripon. Keighley Bus Company provides a service to Shipley, Bingley and Keighley. The Yorkshire Coastliner service runs from Leeds to Bridlington, Filey, Scarborough and Whitby via York and Malton. Stagecoach in Hull provides a service to Hull via Goole. Stagecoach Yorkshire provides services to Barnsley.

Rail

From Leeds railway station at New Station Street, West Yorkshire Metro trains operated by Northern run to Leeds' suburbs and onwards to all parts of Leeds City Region. The station is one of the busiest in England outside London, with over 900 trains and 50,000 passengers passing through every day.[135] It provides national and international connections, as well as services to local and regional destinations. The station itself has 17 platforms, making it the largest in England outside London.[136]

The city and metropolitan borough of Leeds is served by 16 railway stations and there are plans to open several more within the next 20 years.[137]

Air

Leeds Bradford International Airport is located in Yeadon, about 8 miles (13 km) to the north-west of the city centre, and has direct flights from 8 UK destinations and 70 international destinations. Scheduled services run between Leeds Bradford Airport and London Heathrow, Amsterdam, Dublin and Barcelona. There is also a direct rail service from Leeds to Manchester Airport.

Recreation

Walking

The Leeds Country Way is a waymarked circular walk of 62 miles (100 km) through the rural outskirts of the city, never more than 7 miles (11 km) from City Square. The Meanwood Valley Trail leads from Woodhouse Moor along Meanwood Beck to Golden Acre Park. The Leeds extension of the Dales Way follows the Meanwood Valley Trail before it branches off to head towards Ilkley and Windermere. Leeds is on the northern section of the Trans Pennine Trail for walkers and cyclists, and the towpath of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal is another popular walking and cycling route. The White Rose Way walking trail to Scarborough begins at City Square. In addition, there are many parks and public footpaths in both the urban and rural parts of Leeds, and The Ramblers' Association, YHA and other walking organisations offer sociable walks. The Ramblers' Association publish various booklets of walks in and around Leeds.[138]

Parks and open spaces

Leeds has many large parks and open spaces. Roundhay Park is the largest park in the city and is one of the largest city parks in Europe. The park has more than 700 acres (2.8 km2)[139] of parkland, lakes, woodland and gardens which are all owned by Leeds City Council. Other parks in the city include: Beckett Park, Bramley Fall Park, Cross Flatts Park, East End Park, Golden Acre Park, Gotts Park,[140] the gardens and grounds of Harewood House, Horforth Hall Park, Meanwood Park, Middleton Park, Potternewton Park, Pudsey Park,[141] Temple Newsam, Western Flatts Park and Woodhouse Moor. There are many more smaller parks and open spaces scattered around the city, which makes Leeds one of the greenest cities in the United Kingdom in a 2017 survey. Leeds was ranked at number seven, just behind Sheffield, but ahead of Bradford, Manchester and Liverpool.[142]

As part of the South Bank regeneration project, there are plans for a new 3.5 hectare city centre park located close to the former Tetley Brewery site.[143] Planning permission for the first phase to be undertaken by Vastint UK was granted in December 2018.[144]

Education

Schools

At the time of the 2001 census Leeds had a population of 183,000 young people aged 0–19 of whom 110,000 were attending local authority schools.[145] In 2008 Education Leeds, a non-profit company owned by Leeds City Council, provided for 220 primary schools, 39 secondary schools and 6 special inclusive learning centres.[146] Under the government Building Schools for the Future initiative, Leeds secured £260m to transform 13 secondary schools into high achieving, e-confident, inclusive schools. The first three of these schools at Allerton High School, Pudsey Grangefield School and Rodillian School were opened in September 2008.[147] The demand for primary school places in Leeds has recently hit a 15-year peak, with an estimated 10,500 new starters this year.[148] The city's oldest and largest private school is the Grammar School at Leeds, which was legally re-created in 2005 following the merger of Leeds Grammar School, established 1552, and Leeds Girls' High School, established 1876. Other independent schools in Leeds include faith schools serving the Jewish[149] and Muslim[150] communities.

Leeds was one of a number of local authorities to try the three-tier system with first, middle and secondary schools. It reverted to the two-tier system in 1992.

Further and higher education

Further education in Leeds is provided by Elliott Hudson College, Leeds City College (formed by a merger in 2009 and having over 60,000 students), Leeds College of Building, and Notre Dame Catholic Sixth Form College.

Institutions providing higher education include:

- The University of Leeds, which received its charter in 1904 having developed from the Yorkshire College which was founded in 1874 and the Leeds School of Medicine of 1831;

- Leeds Beckett University, formerly Leeds Polytechnic, which became a university in 1992 as Leeds Metropolitan University, and can trace its roots to the Mechanics' Institute of 1824;

- Leeds Trinity University, which began in 1966 as two teacher training colleges which merged in 1980 to form Trinity and All Saints College and became a university in 2012;

- Leeds Arts University, formerly Leeds College of Art, which was founded in 1846 as the Leeds School of Art, and became a university in 2017;

- The University of Law, formerly the College of Law, which became a university in 2012 and moved to its current Leeds centre campus from York in 2014;

- Leeds Conservatoire;

- Northern School of Contemporary Dance;

The University of Leeds has about 31,000 students, of which 21,500 are full-time or sandwich undergraduate degree students,[151] Leeds Beckett University has 25,805[152] students of which 12,000 are full-time or sandwich undergraduate degree students and 2,100 full-time or sandwich HND students.[153] Leeds Trinity University has just under 3,000 students.[154] The city was voted the Best UK University Destination by a survey in The Independent newspaper.[155]

Culture

In 2018, Leeds embarked on a five-year cultural investment programme, culminating in a year of cultural celebration in 2023. In 2023 the city will hold an international cultural festival which will harness the energy, creativity and momentum of the bid to be European Capital of Culture 2023, a title the city forwent following the United Kingdom's vote to leave the European Union.[156]

Art

Although the city's municipal art gallery (Leeds Art Gallery) did not open until 1888, art practice and collecting has a long history in Leeds. J. M. W. Turner painted numerous scenes in and around the city,[157] and the city was home to one of Britain's largest collections of Pre-Raphaelite Art, owned by Thomas Plint, during the nineteenth century.[158] There was also an early history of holding large-scale public exhibitions in the city, most notably the series of 'Polytechnic Exhibitions' held regularly from 1839.[159]

Leeds produced many notable artists and sculptors, including Kenneth Armitage, John Atkinson Grimshaw, Jacob Kramer, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Edward Wadsworth and Joash Woodrow, and was the centre for a particularly radical strain of British art. Before the First World War Leeds was the home of an unusual modernist arts organisation, called the Leeds Arts Club, founded by Alfred Orage, which lasted from 1903 to 1923. Notable members included Jacob Kramer, Herbert Read, Frank Rutter and Michael Sadler. As well as advocating a radical political agenda, supporting the Suffragettes, the Independent Labour Party and the Fabian Society, and promoting the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, the Leeds Arts Club was almost unique in Britain as being an exponent of German Expressionist ideas about art and culture. As a result, it staged very early British exhibitions of work by European expressionist artists, such as Wassily Kandinsky, showing their work in the city as early as 1913,[160] and produced its own English Expressionist artists, including Jacob Kramer and Bruce Turner.[161]

In the 1920s Leeds College of Art was the starting point for the careers of the sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, and in the 1950s, and 1960s it was one of the leading centres for radical art education in Britain under the guidance of artists such as Harry Thubron and Tom Hudson, and the art historian Norbert Lynton. Their attempts to redefine what art education should mean in the post-Second World War period led the artist Patrick Heron to claim in 1971 in The Guardian newspaper that "Leeds is the most influential art school in Europe since the Bauhaus".[162] This willingness to push at the boundaries of acceptable public behaviour from artists was also evident in 1966 when Leeds College of Art staged an exhibition of paintings by the Cypriot artist Stass Paraskos, who taught at the college, which was raided by the police after allegations of obscenity.[163]

This radicalism continued into the 1970s when the higher education component of Leeds College of Art was split from the college to form the nucleus of the new multidisciplinary Leeds Polytechnic, now called Leeds Beckett University. Performance art had been taught earlier at Leeds College of Art, notably by the Fluxus artist Robin Page during his time as a tutor there in the mid-1960s, but in 1977 a performance art work hit the national news headlines when the students Pete Parkin and Derek Wain used an air pistol to shoot a line up of live budgerigars in front of an audience at Leeds Polytechnic.[164]

The University of Leeds was the alma mater of Herbert Read, one of the leading international theorists of modern art from the mid-twentieth century,[165] and also the teaching base for the Marxist art historian Arnold Hauser from 1951 to 1985.[166] Partly due to Herbert Read's connection with the University, from 1950 to 1970 the University was the host of one of the first artist-in-residence schemes in Britain, using funding from the then owner of Lund Humphries books, Peter Gregory. The Gregory Fellowships, as the residencies were known, were given to painters and sculptors for up to two years to allow them to develop their own work and influence the University in any way they saw fit. Amongst those holding the fellowships were Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Dennis Creffield and Terry Frost and others. Parallel Gregory Fellowships also existed in music and poetry at the University.[167]

Leeds was also a centre for radical feminist art, with one of the first galleries in Britain dedicated to showing the work of women photographers, the Pavilion Gallery, opening in the city in 1983, and the University of Leeds School of Fine Art being a well-known centre for the development of feminist art history, under Griselda Pollock, during the 1980s and 1990s. Possibly as a result of the strength of feminist art in Leeds, in November 1984 an exhibition of ceramics by students and staff at Leeds Polytechnic was attacked by a group of feminist activists who destroyed eight sculptures on display which they deemed to be degrading to women.[168] The University of Leeds's School of Fine Art also specialised in Art & Language conceptual art practice, under Terry Atkinson, again in the 1980s and 1990s.[169]

A major sculpture research centre and gallery, the Henry Moore Institute, is located alongside Leeds Art Gallery in the city centre, and in 2013 a new contemporary art centre, called The Tetley, opened on the site of the former Tetley Brewery to the south of the city centre.

In March 2017, The Times voted Leeds as the number one cultural place to live in Britain. This was ahead of London, Birmingham, St Ives, Stratford-upon-Avon and Cheltenham. The citation notes that Leeds has Opera North, the Northern Ballet, and the Leeds Playhouse amongst many other attractions that ranked it at number one.[170]

Carnivals and festivals

.jpg)

Leeds West Indian Carnival is Western Europe's oldest West Indian Carnival, and the UK's third-largest after the Notting Hill and Nottingham Carnival.[171][172] It attracts around 100,000 people over 2 days to the streets of Chapeltown and Harehills. There is a large procession that finishes at Potternewton Park, where there are stalls, entertainment and refreshments. The Leeds Festival, featuring some of the biggest names in rock and indie music, takes place every year in Bramham Park. The Leeds Asian Festival, formerly the Leeds Mela, is held in Roundhay Park.[173] The Otley Folk Festival (patron: Nic Jones),[174] Walking Festival,[175] Carnival[176] and Victorian Christmas Fayre[177] are annual events. Light Night Leeds takes place each October, and many venues in the city are open to the public for Heritage Open Days in September.[178] The Leeds International Pianoforte Competition, established in 1963 by Fanny Waterman and Marion Stein, has been held in the city every three years since 1963 and has launched the careers of many major concert pianists. The Leeds International Concert Season, which includes orchestral and choral concerts in Leeds Town Hall and other events, is the largest local authority music programme in the UK.[179]

The Leeds International Film Festival is the largest film festival in England outside London[180] and shows films from around the world. It incorporates the highly successful Leeds Young People's Film Festival, which features exciting and innovative films made both for and by children and young people.[181] Garforth is host to the fortnight-long festival The Garforth Arts Festival which has been an annual event since 2005. The Chapel Allerton Arts Festival is a week-long music and arts event starting in 1998 and held the week after August Bank Holiday each year.[182] The Leeds Festival Fringe is a week long-music festival created in 2010 to showcase local talent in the week prior to Leeds Festival.

Light Night, one of the UK's largest annual arts and light festivals, is a huge fixture on the calendar, taking place in the first week of October, turning the entire city into an art installation with light shows, projections, installations and lots more.[183]

Leeds Pride is an annual LGBT+ festival held since 2006 supported by the city council and local business.[184] In 2018 attendance was 40,000[185] with over 100 floats and benefits the city by over £3.8 million.[185][186][187] The city has a sponsorship scheme for its 15 Rainbow Plaques commemorating places and events that are of significance to the LGBT+ community organised through Leeds Civic Trust.[188]

Other festivals include Transform and Thought Bubble.

Cinema

In October 1888 Louis Le Prince filmed moving picture sequences Roundhay Garden Scene and a Leeds Bridge street scene using his single-lens camera and Eastman's paper film.[189] These were several years before the work of competing inventors such as Auguste and Louis Lumière and Thomas Edison. Today, Leeds International Film Festival's International Short Film Competition is named after Louis Le Prince.[190] The 2015 documentary film The First Film, which first aired at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, documents Le Prince's pioneering status.[191]

Wordsworth Donisthorpe who was also from Leeds, filmed the second-oldest-surviving film. It is not known if he and Louis Le Prince ever met but they both had a strong connection to the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Donisthorpe's patent for a camera to capture the moving image pre dated Le Prince's by twelve years.

Leeds has a rich film exhibition culture. In addition to the Leeds International Film Festival and Leeds Young Film Festival, the city hosts numerous independent cinemas and pop-up venues for film screenings.[192] The Cottage Road Cinema and Hyde Park Picture House have continuously been showing films since 1912 and 1914, respectively, which ranks them among the oldest still-running cinemas in the UK.[193]

Media

Yorkshire Post Newspapers Ltd, owned by Johnston Press plc, is based in the city, and produces a daily morning broadsheet, The Yorkshire Post, and an evening paper, the Yorkshire Evening Post (YEP). The YEP has a website which includes a series of community pages which focus on specific areas of the city.[194] The Wetherby News covers mainly areas within the north eastern sector of the district, and the Wharfedale & Airedale Observer, published in Ilkley, covers the north-west, both appearing weekly. The two largest universities both have student newspapers, the weekly Leeds Student from the University of Leeds and the monthly The Met from Leeds Beckett University. The Leeds Guide was a fortnightly listings magazine, which was established in 1997 and ceased publication in 2012. Free publications include the Leeds Weekly News, produced by Yorkshire Post Newspapers in four geographic versions and distributed to households in the main urban area of the city,[195] and the regional version of Metro which is distributed on buses and at railway stations.

Regional television and radio stations have bases in the city: BBC Television and ITV both have regional studios and broadcasting centres in Leeds, in addition to Channel 4 having recently announced that their national HQ will be located in Leeds.[196] ITV Yorkshire, formerly Yorkshire Television, broadcasts from the Leeds Studios on Kirkstall Road. There are a number of independent film production companies, including the not-for-profit cooperative Leeds Animation Workshop, founded in 1978; community video producers Vera Media and several small commercial production companies. BBC Radio Leeds, Radio Aire, Greatest Hits Radio, Capital Yorkshire, Heart Yorkshire and Yorkshire Radio broadcast from the city. LSRfm.com, is based in Leeds University Union, and regularly hosts outside broadcasts around the city. Many communities within Leeds now have their own local radio stations, such as East Leeds FM and Tempo FM for Wetherby and the surrounding areas.

Made in Leeds is a local television station which launched across the city in 2014.[197] A privately owned television station: Leeds Television is run by volunteers and supported by professionals in the media industry.

Museums

Leeds has over 16 museums and galleries including 9 that are council-run.

A new Leeds City Museum opened in 2008[198] in Millennium Square. Leeds's major museum, it showcases the city's designated collections of local history, world cultures, natural history, archaeology and fine and decorative arts plus a diverse programme of special exhibitions.

Abbey House Museum is housed in the former gatehouse of Kirkstall Abbey, and includes walk-through Victorian streets and galleries describing the history of the abbey, childhood, and Victorian Leeds.

Armley Mills Industrial Museum is housed in what was once the world's largest woollen mill,[199] and includes industrial machinery and railway locomotives. This museum also shows the first known moving pictures in the world which were taken in the city, by Louis Le Prince, of a Roundhay Garden Scene and of Leeds Bridge in 1888. These short film clips can be found on YouTube.

Thwaite Mills Watermill Museum is a fully restored 1820s water-powered mill on the River Aire to the east of the city centre.

The Thackray Museum is a museum of the history of medicine, featuring topics such as Victorian public health, pre-anaesthesia surgery, and safety in childbirth. It is housed in a former workhouse next to St James's Hospital.

The Royal Armouries Museum, the United Kingdom's national collection of arms and armour, opened in 1996 in a dramatic modern building when this part of the collection was transferred from the Tower of London. It is located a short distance from the city centre at Leeds Dock.

Nearby is the Leeds Museum Discovery Centre (formerly housed at the Leeds Museum Resource Centre in Yeadon),[200] the major storage of items not currently on display in museums, and open to the public by appointment.[200][201]

Leeds Art Gallery houses important collections of traditional and contemporary British art, with the best twentieth century collection outside London and a colourful wall painting for the Victorian staircase by Lothar Götz.[202] Just next door, The Henry Moore Institute is dedicated to celebrating sculpture. In the iconic building, they host a year-round changing programme of historical, modern and contemporary exhibitions presenting sculpture from across the world. Located in the striking art deco headquarters of the former brewery, The Tetley is a centre for contemporary art, centred on creativity, innovation and experimentation.

Smaller museums in Leeds include Otley Museum; Horsforth Village Museum;[203] ULITA, an Archive of International Textiles;[204] and the museum at Fulneck Moravian Settlement.

Music, theatre and dance

Leeds is home to the refurbished Grand Theatre where the only national opera company outside London, Opera North, is based.[205] The City Varieties Music Hall is one of the UK's few remaining music halls, and famously hosted performances by Charlie Chaplin and Harry Houdini. It was also the venue of the BBC television programme The Good Old Days. The newest theatre, containing two auditoriums, is the Leeds Playhouse, which had formerly been known as the West Yorkshire Playhouse.[206][207][208] Just south of Leeds Bridge once stood The Theatre which hosted Sarah Siddons and Ching Lau Lauro in 1786 and 1834, respectively.[209][210]

Leeds is also home to Phoenix Dance Theatre, who were formed in the Harehills area of the city in 1981, and Northern Ballet Theatre.[211] In autumn 2010 the two companies moved into a purpose-built dance centre which is the largest space for dance outside London. It is also the only space for dance to house a national classical and a national contemporary dance company alongside each another.[212]

The First Direct Arena[213] opened in September 2013. The 13,500-seater stadium is rapidly becoming the city's number one venue for live music, indoor sports and many other events. Concerts are also held at the O2 Academy, Elland Road, which has hosted groups such as Queen and Kaiser Chiefs, among others and at the universities. Roundhay Park in north Leeds has seen some of the world's biggest artists including Michael Jackson, Madonna, Bruce Springsteen and Robbie Williams.

Popular musical acts originating from Leeds include Soft Cell, Kaiser Chiefs, The Pigeon Detectives, The Wedding Present, The Sunshine Underground, The Sisters of Mercy, Hadouken!, Corinne Bailey Rae, Dinosaur Pile-Up, Pulled Apart by Horses, Gang of Four, Hood, The Rhythm Sisters, Utah Saints, Alt-J and Melanie B of the Spice Girls.[214][215][216][217][218][219]

On Valentine's Day 1970, The Who performed and recorded their album Live at Leeds at the University of Leeds Refectory. Since its initial reception, Live at Leeds has been cited by several music critics as the best live rock recording of all time.[220][221][222]

Pink Floyd's popular second single "See Emily Play" was written in Leeds in 1967 after a gig in the old Leeds City College Technology Campus, then known as Kitson College.[223]

Nightlife

Leeds is Purple Flag accredited to indicate an entertaining, diverse, safe and enjoyable night.[224]

Leeds has the fourth largest student population in the country (over 200,000[225]), and is therefore one of the UK's hotspots for night-life. There are a large number of pubs, bars, nightclubs and restaurants, as well as a multitude of venues for live music. The full range of music tastes is catered for in Leeds. It includes the original home of the famous club nights Back 2 Basics, Speedqueen and Vague.[226] Morley was the location of techno club The Orbit.[227] Leeds has a number of large 'super-clubs' and there is a selection of independent clubs such as Club Mission and Mint Club, which is consistently ranked as one of the world's best clubs by DJ Magazine. Two other Leeds clubs, The Warehouse and The Garage, featured in the Top 100 Clubs list from 2013.[228] The Garage has since closed.

The F Club was club night that ran in Leeds between 1977 and 1982 and specialised in punk rock and post-punk.[229][230] It would prove highly influential to the development of the goth subculture, due to it leading to the formation of seminal gothic rock bands like The Sisters of Mercy, The March Violets and Southern Death Cult.[231] The now-defunct club Le Phonographique was located in the Merrion Centre and was the first gothic nightclub in the world.[232][233]

Leeds has a well established LGBT+ nightlife scene, predominantly located in the Freedom Quarter on Lower Briggate.[234] The New Penny is one of the UK's longest running LGBT+ venues, and Leeds oldest gay bar. The Viaduct Showbar holds drag cabaret, live shows and DJs. Other places include The Bridge, Blayds Bar, Tunnel Leeds and Queens Court.

Popular areas for nightlife in Leeds include Call Lane, Briggate and the Arena Quarter. Towards Millennium Square is a growing entertainment district providing for both students and weekend visitors. The square has many bars and restaurants and a large outdoor screen. Millennium Square is a venue for large seasonal events such as a Christmas market, gigs and concerts, and citywide parties. It is adjacent to the Mandela Gardens, which were opened by Nelson Mandela in 2001. A number of public art features, fountains, and greenery can be found here.

Yorkshire has a great history of real ale,[235] but several bars near the railway station are fusing traditional beers with a modern bar. Popular bars such as this include The Hop, The Cross Keys and The Brewery Tap. Leeds also hosts an annual Leeds International Beer Festival, held at Leeds Town Hall every September.

Markets

Leeds is home to one of the largest indoor markets in Europe,[236] Leeds Kirkgate Market. Leeds also has various regular local markets in Otley, Pudsey, and Yeadon.[237]

There is an annual German Christmas Market based in Millennium Square, usually running from early November to mid-late December.[238]

Sport

The city has teams representing all the major national sports. Leeds United F.C. is the city's main football club, additional clubs include Guiseley AFC and Farsley Celtic. Leeds United was formed in 1919 and plays at the 37,890-capacity Elland Road Stadium in Beeston. The team will play in the Premier League for the first time in sixteen years after they won promotion by winning the EFL Championship in 2019–20. Guiseley was formed in 1909 and plays at the 4,000 capacity Nethermoor Park Stadium in Guiseley. The team plays in the National League North they won promotion to the National League for the first time ever in 2014/15 after beating Chorley 2–3. Farsley Celtic was formed in 1908 and plays in the National League North and their stadium is Throstle Nest.

Leeds Rhinos are the most successful rugby league team in Leeds. In 2009, they became first club to be Super League champions three seasons running, giving them their fourth Super League title.[239] They play their home games at the Headingley Carnegie Stadium. Hunslet, based at the John Charles Centre for Sport, play in the Co-Operative Championship One. East Leeds and Oulton Raiders play in the National Conference League. Bramley Buffaloes (previously Bramley), and Leeds Akkies were members of the Rugby League Conference.

Yorkshire Carnegie are the foremost rugby union team in Leeds and they play at Headingley Carnegie Stadium. They play in the RFU Championship having been relegated from The Guinness Premiership at the end of the 2010–11 season. Otley RUFC are a rugby union club based to the north of the city and compete in National League 2 North, whilst Morley RFC, located in Morley currently play in National Division Three North.

Headingley stadium is home to Yorkshire County Cricket Club which is the most successful cricket team in England, with 33 County Championship wins (including one shared). Their main rivals are Lancashire.

Leeds City Athletic Club competes in the British Athletics League and UK Women's League as well as the Northern Athletics League.

Leeds is home to a number of field hockey clubs that compete in the North Hockey League, Yorkshire Hockey Association League and BUCS leagues. These include Leeds Hockey Club, Leeds Adel Carnegie Hockey Club, the University of Leeds Hockey Club and Leeds Beckett University Hockey Club.[240][241][242][243][244] Leeds Hockey Club Men's 1s gained promotion at the end of the 2016/2017 season to become Leeds's first hockey team competing in a National League.[245]

The City of Leeds Synchronised Swimming Club[246] train at the John Charles Centre for Sport and are represented by swimmers throughout the whole of the North East. The club was founded in 2008 and only compete in National and International Competition.

The city has a wealth of sports facilities including the Elland Road football stadium, a host stadium during the 1996 European Football Championship; the Headingley Carnegie Stadiums, adjacent stadia world-famous for both cricket and rugby league and the John Charles Centre for Sport with an Olympic-sized pool in its Aquatics Centre[247] and includes a multi-use stadium. Other facilities include the Leeds Wall (climbing) and Yeadon Tarn sailing centre. In 1929 the first Ryder Cup of Golf to be held on British soil was competed for at the Moortown Golf club in Leeds and Wetherby has a National Hunt racecourse.[248] In the period 1928 to 1939 speedway racing was staged in Leeds on a track at the greyhound stadium known as Fullerton Park, adjacent to Elland Road. The track entered a team in the 1931 Northern league.

The 2014 Tour de France Grand Départ took place from the Headrow in Leeds city centre on 5 July 2014.

Leeds is well known for its divers and features some of the best diving facilities in the UK. City of Leeds Diving Club, who train at the John Charles Centre for Sport, has trained many athletes who have competed at international and Olympic level, with Jack Laugher and Chris Mears making history by becoming the first ever divers from Great Britain to win an Olympic gold medal, a feat they accomplished at the 2016 Rio Olympics.

Leeds has an ice hockey team, the Leeds Chiefs; they play at the Planet Ice Arena in Beeston, Leeds in the National Ice Hockey League.

Teams

| Club | Discipline | League | Venue | Location | Established | Top flight championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yorkshire County Cricket Club | Cricket | County Championship | Headingley Stadium | Headingley | 1863 | 33 |

| Leeds Rhinos | Rugby league | Super League | Headingley Stadium | Headingley | 1870 | 11 |

| Leeds United | Football | English Premier League | Elland Road Stadium | Beeston | 1919 | 3 |

| Hunslet | Rugby league | League 1 | John Charles Centre for Sport | Hunslet | 1883 | 0 |

| Yorkshire Carnegie | Rugby union | RFU Championship | Headingley Stadium | Headingley | 1991 | 0 |

| Guiseley | Football | National League North | Nethermoor Park | Guiseley | 1909 | 0 |

| Farsley Celtic | Football | National League North | Throstle Nest Stadium | Farsley | 1908 | 0 |

| Leeds Chiefs | Ice hockey | National Ice Hockey League | Planet Ice Leeds | Beeston | 2019 | 0 |

Religion

The majority of people in Leeds identify themselves as Christian.[83] Leeds does not have a Church of England Cathedral: it is in the Anglican Diocese of Leeds (formerly in the Diocese of Ripon and Leeds), headed by the Bishop of Leeds, which has cathedrals in Bradford, Ripon and Wakefield although the Bishop's residence has been in Leeds since 2008. The most important Anglican church is Leeds Minster, although St. George's has the largest congregation by far. Leeds has a Roman Catholic Cathedral, the episcopal seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Leeds. Many other Christian denominations and new religious movements are established in Leeds, including Assemblies of God, Baptist, Christian Scientist, Latter-day Saints ("LDS" or "Mormon"), Community of Christ, Greek Orthodox, Jehovah's Witnesses, Jesus Army, Lutheran, Methodist, Moravian, Nazarene, Newfrontiers, Pentecostal, Salvation Army, Seventh-day Adventist, Society of Friends ("Quakers"), Unitarian, United Reformed, Vineyard, an ecumenical Chinese church, Winners' Chapel and several independent churches.[249][250]