British Chinese

British Chinese (also known as Chinese British, Chinese Britons or British-born Chinese (BBC)) are people of Chinese – particularly Han Chinese – ancestry who reside in the United Kingdom, constituting the second or third-largest group of overseas Chinese in Europe apart from the Chinese diaspora in France and the overseas Chinese community in Russia. The British Chinese community is thought to be the oldest Chinese community in Western Europe, with the first Chinese immigrants having come from the ports of Tianjin and Shanghai (both ports were once held concessions) in the early-nineteenth century to settle in port cities such as Liverpool. They opened restaurants on the ports.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

0.7% of the UK's population (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Greater London, Belfast, Greater Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Glasgow, Cardiff, Newcastle upon Tyne, Nottingham, Edinburgh, Yorkshire and The Humber, South East England, Norwich | |

| Languages | |

| English, Mandarin, Cantonese, Min, Hakka | |

| Religion | |

| Irreligion, Atheism, Taoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Christian Orthodoxy, Judaism, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Overseas Chinese |

Most British Chinese are descended from people who were themselves overseas Chinese when they first arrived in the UK. Most are from former British colonies, such as: Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Mauritius. People from mainland China and Taiwan and their descendants constitute a relatively minor, albeit growing, proportion of the British Chinese community. Chinese communities are found in many major cities including: London, Birmingham, Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Cardiff, Sheffield, Nottingham, Belfast, and Aberdeen.

Compared with most ethnic minorities in the UK, the Chinese are socioeconomically more widespread and decentralised, have a record of high academic achievement, and have the second highest household income among demographic groups in the UK, after British Indians.[1]

History

First visitor, first immigrant and first to be naturalised

The first recorded Chinese person in Britain was Shen Fu Tsong, a Jesuit scholar who was present in the court of King James II in the 17th century. Shen was the first person to catalogue the Chinese books in the Bodleian Library. The King was so taken with him he had his portrait painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller and hung it in his bed chamber. The portrait of Shen is in the Royal Collection; it currently hangs in Windsor Castle.[2]

William Macao was the earliest recorded Chinese person to settle in Britain. He lived in Edinburgh, Scotland from 1779. Macao married a British woman and had children, and was the first Chinese person to be baptised into the Church of Scotland. He worked for The Board of Excise at Dundas House, St Andrew Square, Edinburgh for 40 years, beginning as a servant to the clerks and retiring as Senior Accountant. He was involved in a significant naturalisation law case and for two years, until the first decision was overturned on appeal, was legally deemed a naturalised Scotsman.[3][4]

A Chinese man known as John Anthony (d. 1805) was brought to London in 1799 by the East India Company to provide accommodation for the Lascar and Chinese sailors in Angel Gardens, Shadwell in London's East End. Antony had left China around 11 years of age in the 1770s making several journeys between London and China. He converted to the Church of England and anglicised his name, settled in London, and married Ester Gole in 1799.[5] Wishing to buy property, but unable to so while an alien, in 1805 he used part of the fortune he had amassed from his London work to pay for an Act of Parliament to naturalise him as a British subject; thus being the first Chinese person to gain British citizenship.[6] However, he died a few months after the Act was passed.[7]

The British East India Company which controlled the importation of popular Chinese commodities such as tea, ceramics and silks began employing Chinese seamen from the early 1880s. Those who crewed ships to Britain had to spend time in London's dock area while waiting for a ship to return to China and so the Limehouse area became the site of the first Chinatown in Britain.

Chinese New Year

The Chinese New Year, or Spring Festival, is the most important celebration for Chinese and other East Asian communities. It links overseas Chinese and their descendants to their heritage, even though they live thousands of miles away from their ancestral homelands. Celebrations for Chinese people are of great traditional significance and include a ritual cleaning of their houses and visit to the temple, but also involve feasting with the family, celebration, fireworks, and gift-giving. This festival follows the lunar calendar so it can fall any time from late January to mid-February and begins on the first day of a new moon and ends with the full moon on the day of the Lantern Festival.

Celebrations in London are famous for colourful parades, fireworks, and street dancing. The route starts in the Strand and goes along Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue. Other activities include a family show in Trafalgar Square with dragon and lion dances and traditional and contemporary Chinese arts by performers from both London and China. There are fireworks displays in Leicester Square, as well as cultural stalls, food, decorations, and lion dance displays throughout the day in London Chinatown.

Community

There are Chinatowns and Chinese community centres in almost every place where there is a substantial Chinese community, and new immigrants and long term citizens can find help and support there.

There are also many activities of interest to new generations and the community at large, such as women's groups, health talks, day trips, cookery sessions, English-language classes, and IT training courses. There are celebrations of Chinese and British festivals, volunteer groups to help members of the community, as well as a work experience scheme for local school students to spend placements working within businesses in the community.

There exist several organisations in the UK that support the Chinese community. The Chinese community is a non-profit organisation that runs social events for the Chinese community. Dimsum is a media organisation which also aims to raise awareness of the cultural issues that the Chinese community face.[8] The Chinese Information and Advice Centre supports disadvantaged people of Chinese ethnic origin in the UK.

Since 2000, the emergence of Internet discussion sites produced by British Chinese young people has provided an important forum for many of them to grapple with questions concerning their identities, experiences, and status in Britain.[9] Within these online fora and in larger community efforts, the groups may self identify as 'British-born Chinese' or 'BBCs'.[10]

Chinatowns

In several major cities there are Chinatowns, which have become tourist attractions where Chinese restaurants and businesses predominate, although in some cases relatively few Chinese people may live there. There are Chinatowns in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle, Sheffield and Aberdeen.

London

.jpg)

There are Chinese community centres in Chinatown, Barnet, Camden, Hackney, Islington, Lambeth, Haringey and Tower Hamlets. Major organisations include the London Chinese Community Centre, London Chinatown Chinese Association, the London Chinese Cultural Centre.

The Westminster Chinese Library, based at the Charing Cross Library (simplified Chinese: 查宁阁图书馆; traditional Chinese: 查寧閣圖書館; pinyin: Chánínggé Túshūguǎn), holds one of the largest collections of Chinese materials in UK public libraries. It has a collection of over 50,000 Chinese books available for loan and reference to local readers of Chinese; music cassettes, CDs, and video films for loan; community information and general enquiries; a national subscription service of Chinese books; and Chinese events organised from time to time. The library also hosted a photography exhibition in 2013 as part of the British Chinese Heritage project, with photographs and stories of Chinese workers.[11]

Based in Denver House, Bounds Green the Ming-Ai (London) Institute has undertaken a number of heritage and community projects to record and archive the contributions made by British Chinese people to the local communities in the United Kingdom.

The London Dragon Boat Festival is held annually in June at the London Regatta Centre, Royal Albert Docks. It is organised by the London Chinatown Lions Club.[12]

Also held annually in London is the widely acclaimed, British Chinese Food Awards that promotes entrepreneurship, talent and Chinese food across the UK.

Contemporary issues

Language poses a serious problem for the older generation and for women working at home. Isolation and depression are common and, increasingly, Chinese community groups are providing advocacy and counselling to alleviate these problems. For men in the catering trade, unsociable hours and the lack of after-hours venues has led to the problem of late-night gambling clubs.

Accommodation tied to work is still common practice for those working in restaurants. As a result, homelessness is a serious issue faced by many elderly retirees. Limited access to Chinese-speaking housing associations makes it harder for them to obtain advice on housing and rights.

For older Chinese Londoners, tri-lingual community centres are an invaluable resource providing essential advice and services. For the younger generation of British-born Chinese, these centres provide a meaningful way to participate in their community and keep in touch with their language and cultural identity.

The connection between China and London has developed recently, with Beijing hosting the 2008 Olympic Games, before handing the baton on to London. A series of cultural and business exchanges and exhibitions have increased awareness about Chinese culture for many Londoners. The Trafalgar Square celebration of Chinese New Year is now a firm fixture on London's Festival Calendar.

Arts

The Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (CFCCA)[13] is the international agency for the development and promotion of contemporary Chinese artists. Established in 1986, it is based in Manchester, the city with the second largest Chinese community in the UK, and the organisation is part of the region's rich Chinese heritage. The Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art also hosts the International Chinese Live Art Festival[14] which showcases work by Chinese artists from across the world.

The Yellow Earth Theatre company is a London-based international touring company formed by five British East Asian performers in 1995. It aims to promote the writing and performing talents of East Asians in Britain.[15]

The China Arts Space is an organisation that promotes East Asian visual and performing arts.[16] British lecturers Dr Felicia Chan and Dr Andy Willis, of the University of Manchester and University of Salford respectively, have proposed that artists of Chinese heritage in the UK were accepted inclusively under the label British Asian in the 1980s.[17]

Music

KT Tunstall is a well-known Scottish singer-songwriter and guitarist whose maternal grandmother was Chinese.[18]

Film and television

British Chinese film and television productions include:

- The Chinese Detective, (1981–1982) television series

- Ping Pong (1986) directed by Po-Chih Leong[19]

- Soursweet (1988) directed by Mike Newell[20]

- Peggy Su! (1997) directed by Frances-Anne Solomon[21]

- Dim Sum (A Little Bit of Heart) (2002) directed by Jane Wong[22]

- The Missing Chink (2004) directed by Kate Solomon[23]

- Sweet & Sour Comedy (2004) directed by Neil A. McLennan[24]

- Spirit Warriors (2010) television series created by Jo Ho starring Jessica Henwick, Benedict Wong, Tom Wu and Burt Kwouk[25]

Books and publishing

Huang Yongjun, the founder and General Manager of New Classic Press (UK) has acted as a major advocator of the "China Dream" in the United Kingdom. The New Classic Press that he founded is an effort to "explain China to the world".[26]

Demographics

Britain has been receiving ethnic Chinese migrants more or less uninterruptedly on varying scales since the 19th century. While new immigrant arrivals numerically have replenished the Chinese community, they have also added to its complexity and the already existing cleavages within the community. Meanwhile, new generations of British-born Chinese have emerged. The educational success of the younger, British-born Chinese has brought professional and economic prosperity to the Chinese community.

Main migration waves

Chinese migration to Britain has a history of at least 150 years. Between 1800 and 1945 it is estimated 20,000 had emigrated to Britain.[27] In 1901 there were 387 Chinese people living in Britain, in 1911, 1,219.[28] Until the Second World War, Chinese communities lived around Britain's main ports, the oldest and largest in Liverpool and London. These communities consisted of a transnational and highly mobile population of Cantonese seamen and small numbers of more permanent residents who ran shops, restaurants, and boarding houses that catered for them.[29] The number of Chinese seamen (who mainly worked as stokers) dwindled sharply during the Depression and the subsequent decline of coal-fired intercontinental shipping after the Second World War. In the 1950s, they were replaced by a rapidly growing population of Chinese from the rural areas in Hong Kong's New Territories. Opening restaurants across Britain, they established firm migration chains and soon dominated the Chinese presence in Britain.[30] In the 1960s and 1970s, they were joined by increasing numbers of Chinese students and economic migrants from Malaysia and Singapore.

Chinese migration to Britain continued to be dominated by these groups until the 1980s, when rising living standards and urbanization in Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia gradually reduced the volume of migration from the former British Colonies. At the same time in the 1980s, the number of students and skilled emigrants from the People's Republic of China began to rise. Since the early 1990s, the UK has also witnessed a rising inflow of economic migrants from areas in China without any previous migratory link to the UK, or even elsewhere in Europe. A relatively small number of Chinese enter Britain legally as skilled migrants. However, most migrants arrive to work in unskilled jobs, originally exclusively in the Chinese ethnic sector (catering, Chinese stores, and wholesale firms), but increasingly also in employment outside this sector (for instance, in agriculture and construction). Migrants who enter Britain for unskilled employment are from both rural and urban backgrounds. Originally, Fujianese migrants were the dominant flow, but more recently increasing numbers of migrants from the Northeast of China have arrived in the UK as well.[31] Migrants now tend to come from an increasing number of regions of origin in China. Some Chinese unskilled migrants enter illegally to work in the black economy, in dangerous jobs with no employment rights, as the Morecambe Bay tragedy of February 2004 showed. Some claim asylum in-country, avoiding deportation after exhausting their appeals.

Population

The population figure of 247,403 (approximately 0.5% of the UK population and around 5% of the total non-white population in the UK), cited from figures produced by the UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS), is based on the 2001 national census. However, it may not be an entirely accurate figure of the current population of people of Chinese origin in the UK. Reasons for this include: some had not participated in the 2001 national census, some had not specified their ethnic group in the census, either intentionally or unintentionally, and successive Chinese migration to or from the UK since 2001. A recent publication from the ONS, "Focus on Ethnicity and Religion (October) 2006",[32] gave some detailed figures on the makeup of the UK's Chinese population that were based on the information by those who had identified themselves as 'Chinese' in the United Kingdom Census 2001.

- Total population: Over 400,000 (2006), not including those of partial Chinese descent[33]

- Geographical distribution: 33% of the Chinese in Britain live in London, 13.6% in the South East, 11.1% in the North West.

- Birthplace: 29% in Hong Kong, 25% England, 19% Mainland China, 8% Malaysia, 4% Vietnam, 3% Singapore, 2.4% Scotland, 2% Taiwan, 0.9% Wales, 0.1% Northern Ireland.

- Occupation: Of all ethnic groups, Chinese had the highest proportion as students (about a third) and the lowest in "routine/manual" occupations (17%).

| Religious affiliation |

Population % 2001 |

Population % 2011[34] |

|---|---|---|

| Not religious | 52% | 55.6% |

| Christianity | 25.1% | 19.6% |

| Buddhism | 15.1% | 12.6% |

| Other | 7.8% | 12.2% |

In the United Kingdom, "Asian demographics" and "Chinese demographics" are separate. In British usage, the word "Asian" or "British Asian" when describing people usually refers to those from South Asia (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Maldives, etc.).

Geographic distribution

Compared with most ethnic minorities in the UK, the Chinese tend to be more widespread and decentralised. However, significant numbers of British Chinese people can be found in Birmingham, Brighton, Cambridge, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London, Manchester, Milton Keynes, Hull, Nottingham, Oxford, Sheffield, and Swansea. In Northern Ireland, Chinese make up the largest non-white minority, although the population of roughly 4,000 is relatively small.

Many locations with a high visible Chinese cultural presence are called Chinatowns. Liverpool's Chinatown is situated around the Berry Street and Duke Street area in the city centre. The Ceremonial Archway, which was built in Shanghai, China, is located at the heart of Liverpool's Chinatown. Before World War II, the original Chinatown was situated around Pitt Street. In London, there is a Chinatown centred around Gerrard Street, Soho, in the West End of central London which has many Chinese restaurants and businesses; it is mostly a commercial area, most Chinese live in other parts of London, especially north London and Colindale in particular. Sheffield's unofficial Chinatown is located at London Road.

Languages

According to the website www.Ethnologue.com, Yue Chinese (Cantonese) is spoken by 300,000 Britons as a primary language, whilst 12,000 Britons speak Mandarin Chinese and 10,000 speak Hakka Chinese. The proportion of British Chinese people who speak English as a first or second language is unknown.[35] but note that 'Mandarin' is an English term for a version of Chinese (known as Putonghua in Chinese, a term that translates as anything but a marker of a language spoken by an educated elite). However, this is the least of numerous sources of confusion.

Largest urban Chinese communities

(2005 estimates)[36]

- London – 107,100 (1.4%)

- Manchester – 10,800 (2.3%)

- Birmingham – 10,700 (1.1%)

- Liverpool – 6,800 (1.5%)

- Nottingham – 5,998 (1.9%)[37]

- Sheffield – 5,100 (1.0%)

- Oxford – 4,200 (2.9%)

- Cambridge – 3,600 (3.1%)

- Newcastle upon Tyne – 3,100 (1.1%)

- Glasgow – 10,689 (1.8%)[38]

- Edinburgh – 8,076 (1.7%)[39]

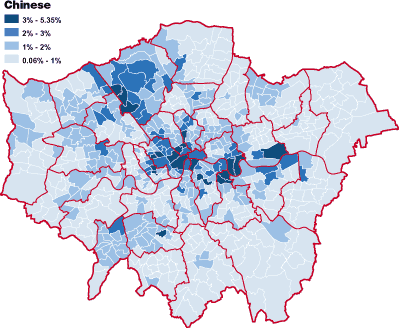

London demography

According to the Census statistics, there was only one ward in London with a more than 5% Chinese population, which was Millwall in Tower Hamlets at 5.4%.[40] The Chinese population is extremely dispersed, according to Rob Lewis, a senior demographer at the Greater London Authority: "The reason for their thin spread all over London, is because of the idea that you want to set up a Chinese restaurant that's a little way away from the next one."[41]

| Borough | Total population | Chinese population | Chinese percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| City of London* | 7,700 | 100 | 1.3 |

| Barking and Dagenham | 165,500 | 1,500 | 0.9 |

| Barnet | 326,100 | 7,600 | 2.3 |

| Bexley | 221,000 | 1,800 | 0.8 |

| Brent | 270,300 | 3,500 | 1.3 |

| Bromley | 297,900 | 2,200 | 0.7 |

| Camden | 222,800 | 6,000 | 2.7 |

| Croydon | 335,800 | 2,700 | 0.8 |

| Ealing | 305,700 | 4,400 | 1.4 |

| Enfield | 283,400 | 3,000 | 1.1 |

| Greenwich | 221,600 | 3,400 | 1.5 |

| Hackney | 207,100 | 2,800 | 1.4 |

| Hammersmith and Fulham | 171,000 | 1,800 | 1.1 |

| Haringey | 224,100 | 3,400 | 1.5 |

| Harrow | 214,000 | 2,900 | 1.4 |

| Havering | 226,300 | 1,100 | 0.5 |

| Hillingdon | 247,900 | 2,700 | 1.1 |

| Hounslow | 216,600 | 2,000 | 0.9 |

| Islington | 184,200 | 4,300 | 2.3 |

| Kensington and Chelsea | 175,800 | 4,700 | 2.7 |

| Kingston upon Thames | 153,900 | 2,500 | 1.6 |

| Lambeth | 270,300 | 3,500 | 1.3 |

| Lewisham | 253,200 | 3,500 | 1.4 |

| Merton | 195,300 | 2,900 | 1.5 |

| Newham | 249,700 | 3,400 | 1.4 |

| Redbridge | 249,000 | 2,600 | 1.0 |

| Richmond upon Thames | 178,000 | 1,600 | 0.9 |

| Southwark | 264,000 | 6,800 | 2.6 |

| Sutton | 183,100 | 1,500 | 0.8 |

| Tower Hamlets | 209,400 | 4,900 | 2.3 |

| Waltham Forest | 220,300 | 2,000 | 0.9 |

| Wandsworth | 276,400 | 2,700 | 1.0 |

| Westminster | 228,600 | 7,300 | 3.2 |

| London | 7,456,000 | 107,100 | 1.4 |

- *not a London Borough

Socioeconomics

Since the relatively elevated immigration of the 1960s, the Chinese community has made rapid socioeconomic advancements in the UK over the course of a generation. There still exists a segregation of the Chinese in the labour market, however, with a large proportion of the Chinese employed in the Chinese catering industry.[42] Overall, as a demographic group, the British Chinese are well-educated and earn higher incomes when compared to other demographic groups in the UK. The British Chinese also fare well on many socioeconomic indicators, including low incarceration rates and high rates of health.[43]

Education

The British Chinese community place an exceptionally high value on post-secondary educational attainment; emphasize effort over innate ability; give their children supplementary tutoring irrespective of financial barriers; and restrict their children's exposure to counter-productive influences that might hinder educational attainment via the Confucian paradigm and the sole belief of greater social mobility. The proportion of British Chinese achieving 5 or more good GCSEs stood at a relatively high 70%.[44] According to the 2001 census, 30% of the British Chinese post-16 population are full-time students compared to a UK average of 8%. When it comes to the distinguished category of being recognized as the "paragon immigrants", British Chinese are also more likely to take math and science-intensive courses such as physics and calculus. A study done by the Royal Society of Chemistry and Institute of Physics revealed that British Chinese students were four times more likely than White or Black students in the United Kingdom to achieve three or more science A-levels.[45] In spite of language barriers, among recent Chinese immigrants to the UK (who do not have English as a first language) 86% of pre-teens reached the required standard of English on the national curriculum exam. The overall result of 86% was one percentage point above the British Indians and remained the highest rate among all ethnic groups in the United Kingdom.[46]

The British Chinese community has been hailed as a socioeconomic "success story" by British sociologists, who have for years glossed over socioeconomic difficulties and inequalities among the major ethnic groups in Britain. The degree educational advantages varies widely however: minorities of European descent fare best, together with the British Chinese. The group has more well-educated members, with a much higher proportion of university graduates than British-born whites. These latter have not been negligible: research has shown that the Chinese as a group face both discrimination and problems accessing public and social services. Many have activated ill-conceived stereotypes of the Chinese as a collectivist, conformist, entrepreneurial, ethnic group, and conforming to Confucian values, which is a divergence of British-Chinese culture and construction of ethnic identity. Educational attainment is greatly espoused by parental reasoning as the British Chinese community cites higher education as a route to ensure a higher ranking job.[47]

According to a study done by the London School of Economics in 2010, the British Chinese tend to be better educated and earn more than the general British population as a whole. British Chinese are also more likely to go to more prestigious universities or to get higher class degrees than any other ethnic minority in the United Kingdom. Nearly 45% of British Chinese men and more than a third of British Chinese women achieved a first or higher degree. Between 1995 and 1997, 29% of British Chinese have higher educational qualifications. This was the highest rate for any ethnic group during those two years. Between 2006 and 2008, the figure had risen to 45%, where it again remained the highest for any ethnic group. In terms of educational achievement at the secondary level, Chinese males and females perform well above the national median. A tenth of Chinese boys are ranked in the top 3% overall, and a tenth of Chinese girls in the top 1%.[48] Due to the rigorous primary and secondary school system in East Asian countries such as China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, Britons of Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese descent rank within the top 5 in British as well as international scholastic mathematical and scientific aptitude tests and tend to score better in these subjects than the general population average. British Chinese remain rare among most Special Educational Needs types at the primary and secondary school level, except for Speech, Language and Communication needs, where first-generation Chinese pupils are greatly over-represented with the influx of first-generation immigrants coming from Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.[48]

Employment

First generation British citizens of Chinese backgrounds remain over-represented in self-employment, however, rates of self-employment fell between 1991 and 2001 as second generation British Chinese chose not to follow their parents into business and instead choose to find employment in the paid labor market. First and second-generation British Chinese men have one of the lowest unemployment rates in the nation, with an unemployment rate of 4.08% and 4.32% compared with slightly higher figures of 5% for White Irish (first and second generation).[48] Vertical segregation is also apparent for men and women in the British Chinese community. British Chinese men are twice as likely to be working than White British men to be in professional jobs (27%, and 14% respectively). Chinese men have the third highest rate of employment in managerial jobs at 31%. This compares to 45% for Indian men, 35% for white men and 23% for Black caribbeans.

A colossal rate of diversity in British self-employment and entrepreneurship in the British Chinese Community has been considerably high. East Asian British groups (Chinese, Japanese, South Korean) and British South Asian groups (Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani) typically have higher rates of self-employment than Whites, while Black groups (Black African and Black Caribbean) have lower rates. Self-employment rates in the British Chinese community is generally higher than the national average. For instance, White British had self-employment rates of 17% in 2001, but the British Chinese self-employment rate was 28%, the higher than the British Indian rate of 21%, British Pakistanis of 27%, and the highest overall among Britain's main ethnic groups. However, overall aggregate self-employment fell between the decade of 1991 to 2001 as the proportion of British Chinese with higher qualifications grew from 27% to 43% between the years of 1991 to 2006. 75% of male British Chinese entrepreneurs worked in the distribution, hotel, and catering industries.[49] In 1991, 34.1% of British Chinese men and 20.3% of British Chinese women were self-employed and the rate was the highest among all Britain's major ethnic groups during that year.[50] In 2001, self-employment rates for British Chinese men dropped to 27.8% and 18.3% for British Chinese women, yet overall rates still remained the highest among all of Britain's major ethnic groups. The overall self-employment rate in 2001 was 23%.[51] Common business industries for the British Chinese include restaurants, business services, medical and vet services, recreational and cultural services, wholesale distribution, catering, hotel management, retail, and construction.[52] By 2004, overall British Chinese self-employment was just under 16%, as one in five (21%) of British Pakistanis were self-employed and more British Chinese choose to acquire higher qualifications via education. By 2006, 29% of all Chinese men were classed as self-employed compared to 17% of white British men and 18% of Chinese women compared to 7% of White British women.[53][54]

Economics

British Chinese men and women also rank very highly in terms of receiving wages well above the national median but are less likely to receive a higher net weekly income than any other ethnic group. British Chinese men earn the highest median wage for any ethnic group with £12.70 earned per hour, followed by the medians for White British men at £11.40, and Multiracial Britons at £11.30 and British Indian men at £11.20. British Chinese women also earn a high median wage, third only to Black Caribbean women and Multiracial Briton women with a median wage of £10.21 earned per hour. However British Chinese women are also more likely to experience more pay penalties than other ethnic group in the United Kingdom despite possessing higher qualifications.[48] Women of all ethnic groups have lower mean individual incomes than men in the same ethnic group in the UK. Pakistani and Bangladeshi women have the highest gender income gap while British Chinese have one of the lowest income gender gaps. British Chinese women also have the individual incomes among all ethnic groups in the UK followed by White British and Indian women. Difference in men's incomes and number of children across ethnic groups. British Chinese women have the highest average equivalent incomes among various ethnic groups in the UK. Though British Chinese women have both high individual and equivalent incomes, but they also have very dispersed incomes.[55][56] In 2001, Overall economic activity in the British Chinese community tends to be lower than the general population average.[51]

A study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2011 found out that British Chinese have the lowest poverty rates among different ethnic groups in Britain.[57] The British Chinese adult poverty rate was 20% and the child poverty rate stood at 30%. Of the different ethnic groups studied, Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, and Black British had the highest rates of child and adult poverty overall. In contrast, British Chinese, Black Caribbeans, British Indians and White British had the lowest rates.[57]

Health and welfare

Chinese men and women were the least likely to report their health as "not good" of all ethnic groups. Chinese men and women had the lowest rates of long-term illness or disability which restricts daily activities. The British Chinese population (5.8%) were least likely to be providing informal care (unpaid care to relatives, friends or neighbours). Around 0.25% of the British Chinese population were residents in hospital and other care establishments.[58]

Chinese men (17%) were the least likely to smoke of all ethnic groups. Fewer than 10% of Chinese women smoked. Fewer than 10% of the Chinese adult population drank above the recommended daily alcohol guidelines on their heaviest drinking day.[58]

The Chinese National Healthy Living Centre was founded in 1987 to promote healthy living, and provide access to health services, for the Chinese community in the UK. The community is widely dispersed across the country and currently makes the lowest use of health services of all minority ethnic groups. The Centre aims to reduce the health inequality between the Chinese community and the general population. Language difficulties and long working hours in the catering trade present major obstacles to many Chinese people in accessing mainstream health provision. Language and cultural barriers can result in their being given inappropriate health solutions. Isolation is a common problem amongst this widely dispersed community and can lead to a range of mental illnesses. The Centre, based close to London's Chinatown, provides a range of services designed to tackle both the physical and psychological aspects of health.

Voter registration

A survey conducted in 2006, estimated that around 30% of British Chinese were not on the electoral register, and therefore not able to vote.[59][60] This compares to 6% of whites and 17% for all ethnic minorities.

In a bid to increase voter registration and turnout, and reverse voter apathy within the community, campaigns have been organized such as the British Chinese Register to Vote organised by Get Active UK, a working title that encompasses all the activities run by the Integration of British Chinese into Politics (the British Chinese Project[61]) and its various partners. The campaign wishes to highlight the low awareness of politics among the British Chinese community; to encourage those eligible to vote but not on the electoral register to get registered; and to help people make a difference on issues affecting themselves and their communities on a daily basis by getting their voices heard through voting.[62]

The largest political organisation in the British Chinese community is the Conservative Friends of the Chinese.

Notable individuals

Society and commerce

At the turn of the 20th century, the number of Chinese in Britain was small. Most were sailors who had deserted or been abandoned by their employers after landing in British ports. In the 1880s, some Chinese migrants had fled the US during the anti-Chinese campaign and settled in Britain, where they started up businesses based on their experience in America. There is little evidence to suggest that these "double migrants" had established close ties with Britain's other, longer-standing Chinese community. By the middle of the 20th century, the community was on the point of extinction, and would probably have lost its cultural distinctiveness if not for the arrival of tens of thousands of Hong Kong Chinese in the 1950s.

Starting a small business was the main way the Chinese coped with their limited ability to find employment in a generally alien and hostile English-speaking environment. They forged inter-ethnic partnerships to overcome the twin problem of raising funds and finding employees. In the first half of the 20th century, most Chinese were involved in the laundry business, while migrants who arrived after the Second World War worked primarily in the catering industry. As these businesses grew, so too did the demand for labour, which entrepreneurs met by exploiting kinship ties to bring family members into Britain. Business partnerships broke up and evolved into family firms, starting and gradually reinforcing the move away from community-based enterprise. With this, competition escalated, since most migrants were involved in the same sector of industry.

This competition necessitated the community's geographical dispersal which further hindered its attempts to struggle collectively for greater protection from the authorities against racial discrimination. In urban areas, the experience of racism forced the Chinese into "ethnic niches", consisting primarily of restaurants and takeaways, thus heightening competition and placing further limits on communal cooperation. The more entrepreneurial of these migrants would strive to leave these enclaves and were usually the ones who achieved social mobility. Later arrivals—the seafarers (in the first half of the 20th century) and immigrants from Hong Kong (from the 1960s)—were unable to cooperate to challenge the policies of the British government which were designed to prevent them from entering other economic sectors, even as part of the labour force. In addition to the generalised racism that they encountered, these Chinese migrants were trapped by policies to remain in economic spheres where their links with the majority population were curtailed and competition with the latter was minimized.

Government policies also had an important bearing on the issues of integration and enterprise development. The Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher in the late 1970s and early 1980s actively promoted the setting up of small enterprises, essentially as a mechanism to deal with the problem of racism.[63] The government was then of the view that since immigrants preferred to concentrate on small businesses due to the hardships and difficulties, in the form of language barriers and racial discrimination they experienced in the UK, they would opt for opportunities for business ownership rather than employment with or by non co-ethnics.

While small enterprises have helped migrants to cope with the problem of their isolation and alienation in the new environment, a good segment of their children, on the other hand, have done well in education, notably at the tertiary level, and have made a prominent presence as professionals and in the high-tech sector.[64]

By the turn of this century, the Chinese in the UK could be broadly categorized into four main categories:

- Hong Kong Chinese from the rural New Territories who started arriving in large numbers in the 1950s and 1960s. Many of them moved into catering and food wholesaling and retailing.

- Southeast Asian Chinese, who also started arriving in the 1960s. Primarily from middle-class, professional backgrounds, some of them have also gone into business, including catering.

- Arrivals from mainland China and urban Hong Kong in the 1980s, who have gone into business related to technology and manufacturing.

- British-born Chinese, whose members are mostly well-qualified and work in hi-tech industries.[65]

The lists of directors and shareholders of Chinese-owned companies provide no evidence of interlocking stock ownership or of interlocking directorships. A number of them were created and ran as partnerships before coming under the control of one individual or family. Most of the start-up funds for these businesses have come from personal savings or put together by family members. There is little evidence that they have had access to ethnic-based funding, and there are very few instances to suggest that financial aid has been provided on intra-ethnic grounds; rather, such assistance was for the mutual benefit of both borrower and lender.[66] An example of an ethnic Chinese who capitalised on his ethnicity to create a Chinese-based business in the UK is Woon Wing Yip. An immigrant from Hong Kong who started out as a waiter, Yip became a restaurateur and later built his reputation as a leading wholesaler and retailer of Chinese food products. He is the owner of Britain's largest Chinese enterprise in terms of sales volume.[67]

See also

- Britons in Hong Kong

- British-Chinese relations

- British nationality law and Hong Kong

- Jook-sing

Footnotes

- In British nationality law, a person can be born, naturalised or registered as a British citizen. This difference in the law is not important in this article.

- Ethnic Chinese people who are British citizens but not resident in the UK are not a main concern of this article, including ethnic Chinese people who had obtained British Citizenship in Hong Kong prior to handover who do not normally reside in the UK. Ethnically Chinese people who are British citizens and living outside the UK are "British Chinese" in one sense of the term, but those holding a British National (Overseas) passport and living outside the UK are not normally considered to be "British Chinese", as they do not normally hold the right of abode in the UK.

References

- https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/work-pay-and-benefits/pay-and-income/household-income/latest

- "Chinese in Britain – Episode 1: The first Chinese VIPs", BBC Radio 4, 2008, accessed 28 March 2011. *Batchelor, Robert K. "Shen Fuzong", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, May 2010, accessed 28 March 2011. (subscription required)

- Price, Barclay (2019). The Chinese in Britain - a history of visitors and settlers. UK: Amberley Books. ISBN 9781445686646.

- Horne, Marc. "Extraordinary tale of first Chinese Scotsman". ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- Pandey, Gyanendra (March 2013). Subalternity and Difference: Investigations from the North and the South. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-70162-7.

- The Gentleman’s Magazine, August 1805 – obituary of John Anthony

- Hahn, Sylvia; Nadel, Stanley (2014). Asian Migrants in Europe: Transcultural Connections. V&R unipress GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8471-0254-0.

- Casciani, Dominic. "Chinese Britain", BBC News, 2002, accessed 28 March 2011.

- Parker, David; Song, Miri. (2007). "Inclusion, Participation and the Emergence of British Chinese Websites", Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(7): 1043–1061. (subscription required)

- Garner, Steve (2009), Racisms: An Introduction, Sage Publications, p. , ISBN 978-1-4129-4581-3

- "Libraries events archive 2013". City of Westminster. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "London Chinatown Lions Club", London Chinatown Lions Club, accessed 28 March 2011. Archived 27 March 2011.

- "CFCCA". 13 June 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "International Chinese Live Art Festival". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Tristram Fane Saunders (20 March 2017). "The 'yellowface' row proved British theatre is stuck in the past - but could a new play bring it forward?". The Daily Telegraph.

The play is staged in a Peter Brook-esque empty space, and has a British Asian cast led by 42-year-old actress Lourdes Faberes as the titular warlord.

- Allen, Daniel. "London caught in a China vibe", Asia Times, 21 April 2009, accessed 28 March 2011. Archived 27 March 2011.

- Felicia Chan; Andy Willis (2018). "Manchester's Chinese Arts Centre: A Case Study in Strategic Cultural Intervention". In Ashley Thorpe; Diana Yeh (eds.). Contesting British Chinese Culture. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-3319711591.

The presence of British Asian artists and that term, whatever its accepted usage might be and for however brief a period, was inclusive when it came to artists of Chinese origin.

- Montgomery, James. "KT Tunstall Outdoes The Cure, But Label Still Won't Trust Her". MTV. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- Jason C. Atwood (1 November 1990). "Ping Pong (1987)". IMDb. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Soursweet (1988)". IMDb. 1 December 1989. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- hengir (14 August 1997). "Peggy Su! (1997)". IMDb. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Dim Sum (A Little Bit of Heart) (2002)". IMDb. 1 August 2002. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "The Missing Chink (2004)". IMDb. 17 January 2004. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Sweet & Sour Comedy (2004)". IMDb. 22 March 2004. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Liz Bassett. "Spirit Warriors (TV Series 2009– )". IMDb. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Home – Zentopia Culture". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- p44 (2014-09-11). history of immigration to britain. ISBN 9781317864233.

- JP, May. The Chinese in Britain. p. 121.

- Parker, David. 1998. Chinese People in Britain: Histories, Futures and Identities. In The Chinese in Europe (eds) G. Benton & F.N. Pieke. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Watson, James L. 1974. Restaurants and Remittances: Chinese Emigrant Workers in London. In Anthropologists in Cities (eds) G.M. Foster & R.V. Kemper. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Pieke, Frank N., Pál Nyíri, Mette Thunø & Antonella Ceccagno. 2004. Transnational Chinese: Fujianese Migrants in Europe. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- "National Statistics 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Office for National Statistics (ONS) – ONS". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- United Kingdom Census 2011: DC2201EW – Ethnic group and religion (Excel sheet 21Kb) ONS. 2015-09-15. Retrieved on 2016-01-14.

- "United Kingdom". Ethnologue. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Check Browser Settings". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Services, Good Stuff IT. "Nottingham – UK Census Data 2011". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "crer" (PDF). crer.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2013-12-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- What the maps don't show 21 January 2005

- "London by ethnicity: Analysis". the Guardian. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Pang, Mary; Lau, Agnes. "The Chinese in Britain: working towards success?", International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1 October 1998, 9(5): 862–874. (subscription required)

- "Offender Management Caseload Statistics 2007" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.

- Mike Baker. "Educational achievement". BBC News. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- Jeremy Crook (October 12, 2010). "Time for White and Black families to learn from the Chinese community". Black Training & Enterprise Group. Archived from the original on 2012-01-06. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- "British Chinese kids on top". Times of India. Feb 16, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- Becky Francis (2005). "School of Education: Research papers from the School of Education" (PDF). British-Chinese pupils’ and parents’ constructions of the value of education. Roehampton University. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- "An Anatomy of Economic Inequality in the UK" (PDF). Report of the National Equality Panel. The London School of Economics – The Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion. 2010-01-29. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- Ken Clark and Stephen Drinkwater (December 2006). "Changing Patterns of Ethnic Minority Self-Employment in Britain: Evidence from Census Microdata" (PDF). University of Manchester and University of Surrey. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- Ken Clark and Stephen Drinkwater (December 2006). "Changing Patterns of Ethnic Minority Self-Employment in Britain: Evidence from Census Microdata" (PDF). Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- "Analysis of Ethnicity in the 2001 Census – Summary Report". The Scottish Government. April 4, 2006. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- David McEvoy (2009). "ETHNIC MINORITY ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN BRITAIN" (PDF). Management & Marketing. 4 (School of Management, University of Bradford).

- "The British Chinese Community" (PDF). Indoor Media Ltd. Feb 2010. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- Ken Clark and Stephen Drinkwater (May 8, 2007). "Changing Rates of Self-employment Among Britain's Asians Suggest Assimilation By Some But Discrimination Against Others". Economics in Action. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- "Ethnic minority women's poverty and economic well being". Government Equalities Office. June 2010. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- "Tackling worklessness". Improvement and Development Agency. Archived from the original on 2012-04-09. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- Lucinda Platt (May 2011). "Inequality within ethnic groups" (PDF). JRF programme paper: Poverty and ethnicity. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- "Office for National Statistics (ONS) – ONS". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Association of Electoral Administrators news article". Archived from the original on 2012-02-17. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "chinesevote.org.uk". Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "British Chinese Project – Non-Profit Organisation". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "UK Chinese – Getting Ready to Vote – Ethnic Now". Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Atkinson, John and David Storey, eds. 1993. Employment, the Small Firm and the Labour Market. London: International Thomson Business Press.

- Berthoud, Richard. 1998. The Incomes of Ethnic Minorities (ISER Report 98-1). Colchester: University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research.

- Benton, Gregor and Edmund Terence Gomez. 2001. Transnationalism and Chinatown: Ethnic Chinese in Europe and Southeast Asia. Canberra: Centre for the Study of the Chinese Southern Diaspora, Australian National University.

- Gomez, Edmund Terence and Gregor Benton. 2004. “Transnationalism and the Essentializing of Capitalism: Chinese Enterprise, the State, and Identity in Britain, Australia, and Southeast Asia”. East Asia: An International Quarterly, 21 (3).

- Inter-Ethnic Relations, Business and Identity: The Chinese in Britain and Malaysia. Edmund Terence Gomez. September 2005. UNRISD programme on Identities, Conflict and Cohesion

Further reading

There have been very few books written on the history of the Chinese in Britain, with what exists are mainly surveys, dissertations, census figures, and newspaper reports. Two books that provide an overview are The Chinese in Britain 1800–Present, Economy, Transnationalism and Identity by Gregor Benton & Edmund Terence Gomez. Palgrave, 2007. This book explores the migration of Chinese to Britain, and their economic and social standing. The other is The Chinese in Britain - A History of Visitors and Settlers by Barclay Price. Amberley 2019. This explores the lives of the Chinese who travelled to Britain over 300 years from the first in 1687.

Books

- Graham Chan (1997) Dim Sum: Little Pieces of Heart, British Chinese Short Stories, contains a collection of 16 short stories that serve up slices of British Chinese experiences and culture. (Crocus Books.)

- Hsiao-Hung Pai (2008) Chinese Whispers: The True Story Behind Britain's Hidden Army of Labour. Penguin.

- Wai-ki E. Luk (2008) Chinatown in Britain: Diffusions and Concentrations of the British New Wave Chinese Immigration. Cambria Press.

- The Chinese in Britain, 1800–Present: Economy, Transnationalism, and Identity by Gregor Benton and E. T. Gomez, Palgrave, 2007.

- Parker, D. "Britain" in L. Pan Ed. (2006) Encyclopaedia of the Chinese Overseas, Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre (revised edition).

- Tam, Suk-Tak. "Representations of 'the Chinese' and 'ethnicity' in British racial discourse". In: Sinn, Elizabeth, ed. The last half century of Chinese overseas. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998. 81–90.

- Maria Lin Wong, Chinese Liverpudlians: A history of the Chinese community in Liverpool (Birkenhead, 1989).

- Shang, Anthony (1984) The Chinese in Britain, London: Batsford.

- Summerskill, Michael. "China on the Western Front. Britain's Chinese work force in the First World War". London: [The author] 1982 236p.

- The Anglo-Chinese author Timothy Mo wrote the Hawthornden Prize-winning and Booker prize-shortlisted novel Sour Sweet about a Chinese family running a restaurant in late sixties and seventies London who fall foul of a group of Triads.[1]

- Choo, Ng Kwee, The Chinese in London (London, 1968).

- May, John, "The Chinese in Britain, 1869–1914" in Colin Holmes (ed.), Immigrants and Minorities in British Society (London, 1978), pp. 111–124.

Chapters:

- Parker, David. Chinese people in Britain: histories, futures and identities. In: Benton, Gregor; Pieke, Frank N., eds. The Chinese in Europe. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. 390p. 1998 67–95

- Parker, David. Emerging British Chinese identities: issues and problems. In: Sinn, Elizabeth, ed. The last half century of Chinese overseas. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1998. 508p. 1998 91–114

- Parker, David. Rethinking British Chinese identities. In: Skelton, Tracey; Valentine, Gill, eds. Cool places: geographies of youth cultures. London; New York: Routledge, 1998. 66–82

- Baker, Hugh D.R. Nor good red herring: the Chinese in Britain. In: Shaw, Yu-ming, ed. China and Europe in the twentieth century. Taipei: Institute of International Relations, National Chengchi University, 1986. 318p. 1986 306–315

Papers

- Graham Chan. "The Chinese in Britain". Adapted from an article originally published in Brushstrokes, issue 12, June 1999. For additional articles and stories go to Graham Chan's website

- John Seed. ‘"Limehouse Blues": Looking for Chinatown in the London Docks,1900–1940’, History Workshop Journal, No. 62 (Autumn 2006), pp. 58–85. The Chinese In Limehouse 1900 – 1940. By John Seed 31 January 2007 – A talk at the Museum in Docklands.

- Akilli, Sinan, M.A. "Chinese Immigration to Britain in the Post-WWII Period", Hacettepe University, Turkey. Postimperial and Postcolonial Literature in English, 15 May 2003

- Archer, L. and Francis, B. (December 2005) "Constructions of racism by British Chinese pupils and parents", Race, Ethnicity and Education, Volume 8, Number 4, pp. 387–407(21).

- Archer, L. and Francis, B. (August 2005) "Negotiating the dichotomy of Boffin and Triad: British-Chinese pupils' constructions of 'laddism'", The Sociological Review, Volume 53, Issue 3, Page 495.

- Parker, D and Song M (2007) Inclusion, Participation and the Emergence of British Chinese Websites. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies Vol 33 (7) : 1043–1061.

- ‘Belonging in Britain: The second generation Chinese in Britain’ Miri Song, University of Kent, England (pdf, 13 pages)

- Ethnicity, Social Capital and the Internet: British Chinese Web Sites (pdf, 57 pages)

- Gregory B. Lee, Chinas unlimited: Making the imaginaries of China and Chineseness (London, 2003). An academic study of culture and representation, including testimony from the author's experience growing up in Liverpool.

- Diana Yeh. ‘Ethnicities on the Move: ‘British-Chinese’ art – identity, subjectivity, politics and beyond’, Critical Quarterly, Summer 2000, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 65–91.

- Ng, Alex. "The library needs of the Chinese community in the United Kingdom." London: British Library Research and Development Dept. 1989 102p (British Library research paper, 56.)

- Liu, William H. "Chinese children in Great Britain, their needs and problems". Chinese Culture (Taipei) 16, no.4 (December 1975 133–136)

- Watson, James L. 1974. Restaurants and Remittances: Chinese Emigrant Workers in London. In Anthropologists in Cities (eds) G.M. Foster & R.V. Kemper. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- —. 1976. Emigration and the Chinese Lineage: The Mans in Hong Kong and London. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- —. 1977a. Chinese Emigrant Ties to the Home Community. New Community 5, 343–352.

- —. 1977b. The Chinese: Hong Kong Villagers in the British Catering Trade. In Between Two Cultures: Migrants and Minorities in Britain (ed.) J.L. Watson. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Articles

- BBC History Magazine, May 2007. Features an article about Chinese in Britain by Mukti Jain Campion.

- Chinatown – The Magazine, May/June 2007. Features an article about Chinese in Britain by Anna Chen.

- Venetia Newell, "A Note on the Chinese New Year Celebration in London and Its Socio-Economic Background" Western Folklore, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Jan., 1989), pp. 61–66.

External links

- Chinese Britain: How a second generation wants the voice of its community heard (BBC News)

- Chinese diaspora: Britain (BBC News)

- Chinese Communities – Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674 to 1913

- Silk Screens 19 July 2008 – BBC Video Nation, a series of simultaneous outdoor film screenings and live events in Birmingham, Glasgow, London and Manchester celebrating the lives of the British Chinese in the run-up to the Beijing Summer Olympics. Part of China Now (above).

- Eastern Promises – Spirit Warriors – An ambitious 10-part BBC fantasy drama series broadcast in 2010 on BBC HD, BBC 2 and CBBC. It was the first to star a predominately East Asian cast and was created and written by Jo Ho, the first East Asian person to create a UK drama series. The series combined martial arts with CGI and VFX and starred Jessica Henwick, Benedict Wong, Burt Kwouk and Tom Wu. The series was nominated for "Best Children's Programme" at the Broadcast Awards, 2011. The show is succeeded by a 30 min making of programme Backstage: Spirit Warriors which features interviews with the creator, key cast and crew. archived version

- The Missing Chink – an ironic take mixing comedy and vox-pop on the general low visibility of Chinese people in British society and media, the four 5-minute episodes was broadcast on Channel 4 after the 7 O'Clock News from January 19–22, 2004. It was written by and featured Paul Courtenay-Hyu, and starred Paul Chan, David Yip, Burt Kwouk, Rory Underwood MBE, Matt Wilkinson, Scott Corben and Simone Tully-Kedge. (All four episodes can be seen on YouTube)

- Chinatown – A three-part series broadcast on BBC Two on 24th, 31 January and 7 February 2006, explored in depth the changes taking place in Britain's growing Chinese community.

- BBC – Radio 4 – Chinese in Britain – A groundbreaking ten-part series, "Chinese in Britain", broadcast by BBC Radio 4 in April/May 2007, where presenter and co-writer Anna Chen told the story of the Chinese in Britain from the first known Chinese, Shen Fu Tsong in the 17th century, to the arrival of the migrant wave in the 1950s and 60s. The series was repeated in May 2008. See also: Anna Chen – Writer and performer; Producers: Culture Wise.

- BBC – Radio 4 – Beyond the Takeaway Monday – Friday 10–14 March 2003, 3.45pm – five-part series, actor and director David K.S. Tse, of the Yellow Earth Theatre Company, talks to the BBC, British-born Chinese, about their experiences of growing up and living in Britain.

- Liver Birds and Laundrymen. Europe's Earliest Chinatown Sunday Feature (45 min.) on BBC Radio 3 broadcast on 13 March 2005 21:30–22:15 – Gregory B. Lee, Professor of Chinese at the University of Lyon, returns to his native Liverpool, where his grandfather arrived from China in 1911, to tell a personal history of the earliest Chinese settlement in Europe.

- Eastern Horizon (BBC Manchester), Manchester's first Chinese language radio programme and began broadcasting on 15 December 1983.

- Time Outs China in London – celebrating Chinese history, communities, cuisine, and lifestyle in London

- "Timothy Mo British Council Literature". British Council. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2015.