Baker Street tube station

Baker Street is a London Underground station at the junction of Baker Street and the Marylebone Road in the City of Westminster. It is one of the original stations of the Metropolitan Railway (MR), the world's first underground railway, opened on 10 January 1863.[5]

| Baker Street | |

|---|---|

Station entrance | |

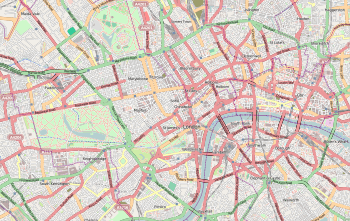

Baker Street Location of Baker Street in Central London | |

| Location | Marylebone |

| Local authority | City of Westminster |

| Managed by | London Underground |

| Number of platforms | 10 |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| OSI | Marylebone |

| London Underground annual entry and exit | |

| 2014 | |

| 2015 | |

| 2016 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2018 | |

| Key dates | |

| 10 January 1863 | Opened (MR) |

| April 1868 | Opened (MR platforms to north) |

| 10 March 1906 | Opened (BS&WR, as terminus) |

| 27 March 1907 | Extended (BSWR – Marylebone) |

| 20 November 1939 | Started (Bakerloo to Stanmore) |

| 1961 | Ended (Met to Aylesbury) |

| 1 May 1979 | Ended (Bakerloo to Stanmore) |

| 1 May 1979 | Started (Jubilee line) |

| 30 July 1990 | Ended (Met to H'smith/Barking) |

| 30 July 1990 | Started (Hammersmith & City) |

| Listed status | |

| Listing grade | II* (since 28 June 2010) |

| Entry number | 1239815[4] |

| Added to list | 26 March 1987 |

| Other information | |

| External links | |

| WGS84 | 51.522°N 0.157°W |

The station is in Travelcard Zone 1 and is served by five lines.[6] On the Circle and Hammersmith & City lines it is between Great Portland Street and Edgware Road. On the Metropolitan line it is between Great Portland Street and Finchley Road. On the Bakerloo line it is between Regent's Park and Marylebone, and on the Jubilee line it is between Bond Street and St. John's Wood.[6]

Location

The station has entrances on Baker Street, Chiltern Street (ticket holders only) and Marylebone Road. Nearby attractions include Regent's Park, Lord's Cricket Ground, the Sherlock Holmes Museum and Madame Tussauds.

History

Metropolitan Railway - the first underground railway

In the first half of the 19th century, the population and physical extent of London grew greatly.[note 1] The congested streets and the distance to the City from the stations to the north and west prompted many attempts to get parliamentary approval to build new railway lines into the City.[note 2] In 1852, Charles Pearson planned a railway from Farringdon to King's Cross. Although the plan was supported by the City, the railway companies were not interested and the company struggled to proceed.[12] The Bayswater, Paddington, and Holborn Bridge Railway Company was established to connect the Great Western Railway's (GWR) Paddington station to Pearson's route at King's Cross.[12] A bill was published in November 1852[13] and in January 1853 the directors held their first meeting and appointed John Fowler as its engineer.[14] Several bills were submitted for a route between Paddington and Farringdon.[15] The company's name was also to be changed again, to Metropolitan Railway[12][16][note 3] and the route was approved on 7 August 1854.[15][17]

Construction began in March 1860;[18] using the "cut-and-cover" method to dig the tunnel.[19][20] Despite having several accidents during construction,[21] work was complete by the end of 1862 at a cost of £1.3 million.[22] Rail services through the station opened to the public on Saturday, 10 January 1863.[23][note 4]

In the next few years, extensions of the line were made at both ends with connections from Paddington to the GWR's Hammersmith and City Railway (H&CR) and at Gloucester Road to the District Railway (DR). From 1871, the MR and the DR operated a joint Inner Circle service between Mansion House and Moorgate Street.[5][note 5]

North-western "branch"

In April 1868, the Metropolitan & St John's Wood Railway (M&SJWR) opened a single-track railway in tunnel to Swiss Cottage from new platforms at Baker Street East (which eventually become the present Metropolitan line platforms).[25][26] The line was worked by the MR with a train every 20 minutes. A junction was built with the original route at Baker Street, but there were no through trains after 1869.[27][note 6]

The M&SJWR branch was extended in 1879 to Willesden Green and, in 1880, to Neasden and Harrow-on-the-Hill.[30] Two years later, the single-track tunnel between Baker Street and Swiss Cottage was duplicated and the M&SJWR was absorbed by the MR.[31][note 7]

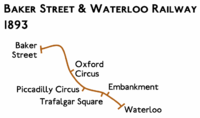

Bakerloo and Jubilee lines

In November 1891, a private bill was presented to Parliament for the construction of the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (BS&WR).[32] The railway was planned to run entirely underground from Marylebone[33] to Elephant & Castle[34] via Baker Street and Waterloo[32] and was approved in 1900.[35][36] Construction commenced in August 1898[37] under the direction of Sir Benjamin Baker, W.R. Galbraith and R.F. Church[38] with building work by Perry & Company of Tredegar Works, Bow.[38][note 8] Test trains began running in 1905.[42] The official opening of the BS&WR by Sir Edwin Cornwall took place on 10 March 1906.[43] The first section of the BS&WR was between Baker Street and Lambeth North.[44] Baker Street was the temporary northern terminus of the line until it was extended to Marylebone on 27 March 1907, a year after the rest of the line.[5][44] The B&SWR's station building designed by Leslie Green stood on Baker Street and served the tube platforms with lifts, but these were supplemented with escalators in 1914, linking the Metropolitan line and the Bakerloo line platforms by a new concourse excavated under the Metropolitan line.[45] An elaborately decorated restaurant and tea-room was added above Green's terminal building, the Chiltern Court Restaurant, which was opened in 1913.[46]

On 1 July 1933, the MR and BS&WR amalgamated with other Underground railways, tramway companies and bus operators to form the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), and the MR became the Metropolitan line, while the BS&WR became the Bakerloo line of London Transport.[47] However, there was a bottleneck on the Metropolitan line at Finchley Road where four tracks merge into two to Baker Street. LPTB decided to extend the Bakerloo line from Baker Street as a branch line, taking over the existing section between Finchley Road and Stanmore.[note 9] Construction began in April 1936. On 20 November 1939, following the construction of an additional southbound platform and connecting tube tunnels between Baker Street and Finchley Road stations, the Bakerloo line took over the Metropolitan line's stopping services between Finchley Road and Wembley Park and its Stanmore branch.[49] [50] The current Bakerloo ticket hall and escalators to the lower concourse were provided in conjunction with the new service.[51]

After the Victoria line had been completed in the 1960s, the new Jubilee line was proposed which would take a route via Baker Street, Bond Street, Trafalgar Square, Strand, Fleet Street, Ludgate Circus and Cannon Street, then proceeding into southeast London.[52] This new line was to have been called the Fleet line.[53] The Jubilee line added an extra northbound platform and replaced the Bakerloo line service to Stanmore from the station, opening on 1 May 1979.[5][54]

Circle and Hammersmith & City lines

The initial route on the Hammersmith & City line was formed by the H&CR, running between Hammersmith and Moorgate. Services were eventually extended to Barking via the DR and shared with the existing MR tracks between Baker Street and Liverpool Street.[5] The route between Hammersmith and Barking was shown on the tube map as part of the Metropolitan line, but since 1990 has been shown separately, the Metropolitan line becoming the route from Aldgate to Baker Street and northwards through "Metro-Land" to Uxbridge, Watford and Amersham.[5][55]

The circle line was initially formed by the combination of the MR and DR routes, which were between Edgware Road and South Kensington, Edgware Road and Aldgate via King's Cross St Pancras, South Kensington and Mansion House,[56][57] and a joint railway between Mansion House and Aldgate.[58][5][59][60] Since 1949, the Circle line is shown separately on the map.[61]

Incidents

On 18 June 1925, electric locomotive No.4 collided with a passenger train when a signal was changed from green to red just as the locomotive was passing it. Six people were injured.[62]

On 23 August 1973, a bomb was found in a carrier bag in the ticket hall.[63] The bomb was defused by the bomb squad. A week later, on 30 August, a member of staff found another bomb left on the overbridge. Again, it was defused without any injury.[64]

The station today

Baker Street station is the combination of three separate stations, with several booking offices throughout its operational years. Major changes took place in 1891-93 and 1910-12. The first part is the Circle Line station, which has its two platforms now used by the Circle and Hammersmith & City lines. They are situated on a roughly east-to-west alignment beneath Marylebone Road, spanning approximately the stretch between Upper Baker Street and Allsop Place. This was part of the original Metropolitan Railway from Bishop's Road (now Paddington (Circle and Hammersmith & City lines) station to Farringdon Street (now Farringdon) which opened on 10 January 1863.[65]

The platforms serving the main branch of the Metropolitan line towards Harrow, Uxbridge and beyond are located within the triangle formed by Marylebone Road, Upper Baker Street and Allsop Place, following the alignment of Allsop place. This station is the second section which opened on 13 April 1868 by the Metropolitan & St. John's Wood Railway. This was later absorbed by the Metropolitan Railway, which is usually known to them as Baker Street East station.[65]

The final section is the deep-level tube station of the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (now part of the Bakerloo line), situated at a lower level beneath the site of Baker Street East, opened on 10 March 1906.[65] This part of the station now contains four platforms which are used by both the Bakerloo and Jubilee lines.[66]

This station is a terminus for some Metropolitan line trains, but there is also a connecting curve that joins to the Circle line just beyond the platforms, allowing Metropolitan line through services to run to Aldgate. The deep-level Bakerloo and Jubilee lines platforms are arranged in a cross-platform interchange layout[67] and there are track connections between the two lines just to the north of the station.[66] Access to the Bakerloo and Jubilee lines is only via escalators.[68]

With ten platforms overall, Baker Street has the most London Underground platforms of any station on the network.[69] Since Swiss Cottage and St. John's Wood have replaced the former three stations between Finchley Road and Baker Street on the Metropolitan line, it takes an average of five and a half minutes to travel between them.[70]

As part of the Transported by Design programme of activities, in 15 October 2015, after two months of public voting, Baker Street underground station's platforms were elected by Londoners as one of the 10 favourite transport design icons.[71][72]

The former Chiltern Court Restaurant above the station is still in use today as the Metropolitan Bar, part of the Wetherspoons pub chain.[46]

Sub-surface platforms

Of the MR's original stations, now the Circle and Hammersmith & City line platforms five and six are the best preserved dating from the station’s opening in 1863. Plaques of the Metropolitan Railway’s coat of arms along the platform and old plans and photographs depict the station which has changed remarkably little in over a hundred and fifty years.[73] Restoration work in the 1980s on the oldest portions of Baker Street station brought it back to something similar to its 1863 appearance.[74]

The Metropolitan line’s platforms one to four were largely the result of the station’s rebuild in the 1920s to cater for the increase in traffic on its outer suburban routes. Today the basic layout remains the same with platforms two and three being through tracks for City services to Aldgate from Amersham, Chesham and Uxbridge flanked by terminal platforms one and four which are the domain of services to and from Watford. The northern end of the platforms is in a cutting being surrounded by Chiltern Court and Selbie House the latter of which houses Baker Street control centre responsible for signalling the Metropolitan line from Preston Road to Aldgate, as well as the Circle and Hammersmith & City lines between Baker Street and Aldgate. The southern end of the platforms are situated in a cut and cover tunnel which runs towards Great Portland Street. All Metropolitan line platforms can function as terminating tracks however under normal circumstance only dead ended platforms one and four are used as such.[75]

Deep-level tube platforms

The Bakerloo line uses platforms eight and nine which date from 10 March 1906 when the Baker Street & Waterloo railway opened between here and Lambeth North (then called Kennington Road). The contraction of the name to "Bakerloo" rapidly caught on, and the official name was changed to match in July 1906.

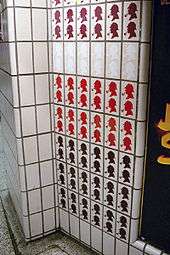

By the mid-1930s, the Metropolitan line was suffering from congestion caused by the limited capacity of its tracks between Baker Street and Finchley Road stations. To relieve this pressure, the network-wide New Works Programme, 1935–1940 included the construction of new sections of tunnel between the Bakerloo line's platforms at Baker Street and Finchley Road and the replacement of three Metropolitan line stations (Lord's, Marlborough Road and Swiss Cottage) between those points with two new Bakerloo stations (St. John's Wood and Swiss Cottage). The Bakerloo line also took over the Metropolitan line's service to Stanmore on 20 November 1939. The branch remained part of the Bakerloo line until 1 May 1979, when similar congestion problems for the Bakerloo line caused by the two branches converging at Baker Street led to the opening of the Jubilee line, initially created by connecting the Stanmore branch to new tunnels bored between Baker Street and Charing Cross. Following refurbishment in the 1980s the original tiling scheme was replaced with tiles depicting the silhouette of Sherlock Holmes who lived at 221B, Baker Street.

The Bakerloo still maintains its connection with the now Jubilee line tracks to Stanmore with tunnels linking from Northbound Bakerloo line platform nine to the Northbound Jubilee line toward St John's Wood and Southbound from Jubilee line platform seven to the Southbound Bakerloo line towards Regents Park.[76] Although no passenger services operate over these sections they can be used for the transfer of engineering trains and was used to transfer Bakerloo line 1972 stock trains to and from Acton Works as part of a refurbishment programme.[77]

Jubilee line trains use platforms seven and ten, which opened in 1979 when the newly built Jubilee line took over existing Bakerloo line services to Stanmore running through new tunnels from Baker Street to Charing Cross to serve as a relief line to the Bakerloo which by now was suffering from capacity issues. In 1999 the Jubilee line was extended from Green Park to Stratford and made the Jubilee line platforms at Charing Cross redundant after twenty years The design of the Jubilee line platforms at Baker Street has changed little since being opened with illustrations depicting famous scenes from Sherlock Holmes cases.

Cross platform interchange is provided between Bakerloo and Jubilee lines in both directions.

Station improvements

Step-free access project

In 2008 TfL proposed a project to provide step-free access to the sub-surface platforms. The project was a TfL-funded Games-enabling project in its investment programme (and not a project specifically funded as a result of the success of the London 2012 Games bid).[78] The project was included in the strategy on accessible transport published by the London 2012 Olympic Delivery Authority and the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games.[79]

Access to the Metropolitan line platforms 1–4 (serving trains to and from Finchley Road) would be provided by a bridge from the Bakerloo and Jubilee line ticket hall, with a lift from the bridge to each island platform. Through a passage from platforms 1–2, this would also give step-free access to platform 5 (Circle and Hammersmith & City line eastbound trains). Access to platform 6 (Circle and Hammersmith & City line westbound trains) would be provided by demolishing the triangular building outside the station, on the north side of Marylebone Road, and taking over the public pedestrian subway under Marylebone Road to provide a link between a lift up from platform 5 to the subway and a lift at the other end of the subway down to platform 6. The replacement for the triangular building would also act as an emergency exit for the station.[80]

TfL applied for planning permission and listed building consent for providing access to platforms 5 and 6 on 1 October 2008, but the application was subsequently withdrawn. (The part of the proposed scheme to provide step-free access to platforms 1–4 is within TfL's permitted development rights, and so does not require planning permission.)[81] TfL announced on 31 March 2009 that because of budgetary constraints the step-free scheme would be deferred.[82]

Platform lengthening

In order to accommodate the new, longer S stock trains, which started operating Metropolitan line services in August 2010, platforms 1 and 4 have been extended.[83] However, the Circle and Hammersmith & City line platforms 5 and 6 have not been extended to accommodate their new S7 Stock trains, due to the enclosed nature of the platforms. Instead selective door operation is employed.

Services

Bakerloo line

On this line, it is between Regent's Park and Marylebone.[6] Trains can terminate at Queen's Park, Stonebridge Park, or Harrow and Wealdstone to the north, and Piccadilly Circus, Lambeth North or Elephant & Castle to the south.[84]

The typical service pattern in trains per hour (tph) operated during off-peak hours is:[85]

- 6tph to Harrow & Wealdstone via Queen's Park and Stonebridge Park (Northbound)

- 3tph to Stonebridge Park via Queen's Park (Northbound)

- 11tph to Queen's Park (Northbound)

- 20tph to Elephant & Castle (Southbound)

Weekday peak service operates with one or two additional Queen's Park-Elephant & Castle trains per hour, and Sunday service operates with two fewer Queen's Park-Elephant & Castle trains per hour during the core of the day.

Jubilee line

The station is situated between Bond Street to the south and St John's Wood to the north. Southbound trains usually terminate at Stratford and North Greenwich although additional turn back points are provided at Green Park, Waterloo, London Bridge, Canary Wharf and West Ham. Northbound trains usually terminate at Stanmore, Wembley Park and Willesden Green although additional turn back points are available at Finchley Road, West Hampstead and Neasden.[86]

The typical off-peak service in trains per hour (tph) is:[87]

- 20tph Southbound to Stratford

- 6tph Southbound to North Greenwich

- 16tph Northbound to Stanmore

- 5tph Northbound to Wembley Park

- 5tph Northbound to Willesden Green

The Night tube service (Friday night to Saturday morning & Saturday night to Sunday morning) in trains per hour is:[87]

- 6tph Southbound to Stratford

- 6tph Northbound to Stanmore

Circle line

The station is between Great Portland Street and Edgware Road on this line as well on the Hammersmith & City line.[6]

The typical service in trains per hour is:[88]

- 6tph Clockwise to Edgware Road via King's Cross St Pancras, Liverpool Street, Tower Hill and Victoria

- 6tph Anti-clockwise to Hammersmith via Paddington

Hammersmith & City line

Between 1 October 1877 and 31 December 1906 some services on the H&CR were extended to Richmond over the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) via its station at Hammersmith (Grove Road).[89][note 10]

The station is between Great Portland Street and Edgware Road on this line, as with the Circle line.[6]

The typical off-peak service in trains per hour (tph) is:[88]

- 6tph Eastbound to Barking or Plaistow

- 6tph Westbound to Hammersmith

Metropolitan line

The Metropolitan line is the only line to operate an express service although currently this is mostly southbound in the morning peaks and northbound in the evening peaks.[90] Southbound fast services run non-stop between Moor Park, Harrow-on-the-Hill and Finchley Road whilst semi-fast services run non stop between Harrow-on-the-Hill and Finchley Road. Northbound fast and semi-fast services call additionally at Wembley Park.[91]

The station is situated between Great Portland Street sharing tracks with the Circle and Hammersmith & City lines in the East and Finchley Road Station to the North. Southbound trains may terminate here and return north towards Uxbridge, Amersham, Chesham, or Watford, where platforms 1 and 4 are used.[66]

The off-peak service in trains per hour is:[91]

- 12tph Southbound to Aldgate

- 4tph Southbound services terminate here

- 2tph Northbound to Amersham (all stations)

- 2tph Northbound to Chesham (all stations)

- 4tph Northbound to Watford (all stations)

- 8tph Northbound to Uxbridge (all stations)

Connections

The station is served by London Bus routes 2, 13, 18, 27, 30, 74, 113, 139, 189, 205, 274 and 453,[92] and also by night routes N18, N74, N113 and N205.[93] In addition, bus routes 27, 139, 189 and 453 have a 24-hour service.[92][93]

Points of interest

In popular culture

The Metropolitan Bar above Baker Street station is featured in Metro-Land, a 1973 documentary film by John Betjeman in which he reminiscences about its genteel origins as the Chiltern Court Restaurant.[94][46]

The excavation of Baker Street for the Underground can be seen in a scene of the 2011 film Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, set in 1891.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- In 1801, approximately one million people lived in the area that is now Greater London. By 1851 this had doubled.[7] The increasing resident population and the development of a commuting population arriving by train each day led to a high level of traffic congestion with huge numbers of carts, cabs, and omnibuses filling the roads and up to 200,000 people entering the City of London, the commercial heart, each day on foot.[8]

- None were successful, and the 1846 Royal Commission investigation into Metropolitan Railway Termini banned construction of new lines or stations in the built-up central area.[9][10] The concept of an underground railway linking the City with the mainline termini was first proposed in the 1830s.[11]

- The original established name was the "North Metropolitan Railway".[15]

- The railway included a ceremonial run from Paddington and a large banquet for 600 shareholders and guests at Farringdon a day earlier.[24] These platforms are now served by the Circle and Hammersmith & City lines.[5]

- After further extensions by the Metropolitan Railway to Liverpool Street (1875), Aldgate (1876) and Tower of London (1882), the Inner Circle was completed in 1884.[5]

- The original intention of the M&SJWR was to run underground north-east to Hampstead Village, and indeed this appeared on some maps.[28] This was not completed in full and the line was built in a north-western direction instead; a short heading of tunnel was built north of Swiss Cottage station in the direction of Hampstead.[29] This is still visible today when travelling on a southbound Metropolitan line service.

- Further extensions took the Metropolitan Railway to Pinner (1885), Rickmansworth (1887), Chesham (1889), Aylesbury (1892), Uxbridge (1904) and Watford (1925).[5]

- By November 1899, the northbound tunnel reached Trafalgar Square and work on some of the station sites was started, but the collapse of the L&GFC in 1900 led to works gradually coming to a halt. When the UERL was formed in April 1902, 50 per cent of the tunnelling and 25 per cent of the station work was completed.[39] With funds in place, work restarted and proceeded at a rate of 73 feet (22.25 m) per week,.[40] By February 1904, most of the tunnels and underground parts of the stations between Elephant & Castle and Marylebone were complete and works on the station buildings were in progress.[41] The additional stations were incorporated as work continued elsewhere.[42]

- In 1929, construction of a spur line from Wembley Park to Stanmore began.[48] It opened on 10 December 1932.[5]

- The L&SWR tracks to Richmond now form part of the London Underground's District line. Stations between Hammersmith and Richmond served by the MR were Ravenscourt Park, Turnham Green, Gunnersbury, and Kew Gardens.[5]

References

- "Out-of-Station Interchanges" (Microsoft Excel). Transport for London. 2 January 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- "Multi-year station entry-and-exit figures (2007-2017)" (XLSX). London Underground station passenger usage data. Transport for London. January 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Station Usage Data" (CSV). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2018. Transport for London. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Historic England. "Baker Street Station: Main Entrance Building and Metropolitan, Circle and Hammersmith & City line platforms (no. 1-6) including retaining wall to Approach Road (1239815)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Rose 2007.

- Standard Tube Map (PDF) (Map). Not to scale. Transport for London. May 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2020.

- "Total Population". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth/Jisc. 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 22.

- Simpson 2003, p. 7.

- "Metropolitan Railway Termini". The Times (19277). 1 July 1846. p. 6. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- "Grand Central Railway Terminus". The Times (19234). 12 May 1846. p. 8. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 9.

- "No. 21386". The London Gazette. 30 November 1852. p. 3480.

- Green 1987, pp. 3–4.

- "Fowler's Ghost" 1962, p. 299.

- "No. 21497". The London Gazette. 25 November 1853. pp. 3403–3405.

- "No. 21581". The London Gazette. 11 August 1854. pp. 2465–2466.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 10.

- Jackson 1986, p. 24.

- Walford 1878.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 36.

- Wolmar 2004, pp. 30 & 37.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 14.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 39.

- Green 1987, p. 11.

- Edwards & Pigram 1988, p. 33.

- Horne 2003, pp. 7–8.

- Demuth & Leboff 1999, p. 9.

- Jackson 1986, pp. 374.

- Horne 2003, p. 13.

- Bruce 1983, p. 20.

- "No. 26225". The London Gazette. 20 November 1891. pp. 6145–6147.

- "No. 26767". The London Gazette. 11 August 1896. pp. 4572–4573.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 84–85.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 56.

- "No. 27218". The London Gazette. 7 August 1900. pp. 4857–4858.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 168.

- Lee, Charles E. (March 1956a). "Jubilee of the Bakerloo Railway – 1". The Railway Magazine. pp. 149–156.

- "The Underground Electric Railways Company Of London (Limited)". The Times (36738). 10 April 1902. p. 12. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 69.

- "Railway And Other Companies – Baker Street and Waterloo Railway". The Times (37319). 17 February 1904. p. 14. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 173.

- Horne 2001, p. 17.

- Feather, Clive (30 December 2014). "Bakerloo line". Clive's Underground Line Guides. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Horne 2001, p. 38.

- Bradley, Simon (2015). The Railways: Nation, Network and People. Profile Books. ISBN 9781847653529. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "No. 33668". The London Gazette. 9 December 1930. pp. 7905–7907.

- Horne 2003, p. 42.

- Horne 2003, pp. 59–61.

- Feather, Clive (5 October 2018). "Metropolitan line". Clive's Underground Line Guides. Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- Horne 2001, p. 48.

- "More Tube lines discussed: Easing travel load". The Times. London. 27 April 1965. p. 7.

- Willis, Jon (1999). Extending the Jubilee Line: The planning story. London Transport. OCLC 637966374.

- Feather, Clive. "Bakerloo line". Clive's Underground Line Guides. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "London Underground map 1990". The London Tube map archive. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- Wolmar 2004, p. 72.

- Lee 1956b, p. 7.

- Jackson 1986, p. 110.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 18.

- Horne 2006, pp. 5–6.

- "1949 tube map". Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Earnshaw, Alan (1989). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 5. Penryn: Atlantic Books. p. 20. ISBN 0-906899-35-4.

- "History of Baker Street Tube Station". Jessica Higgins. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012.

- Nick, Cooper (5 June 2006). "Attacks on the London Underground". The Underground at War. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010.

- Pask, Brian. "Booking Offices at Baker Street" (PDF). Points of Interest. London Underground Railway Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Jarrier, Franklin. "Greater London Transport Tracks Map" (PDF) (Map). CartoMetro London Edition. 3.7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2018.

- "Step free Tube Guide" (PDF). Transport for London. May 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020.

- "Tube Stations that only have escalators". Tube Facts and Figures. Geofftech. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "London Underground: 150 fascinating Tube facts". Telegraph. 9 January 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "Stations that it takes the longest to travel between". Tube Facts and Figures. Geofftech. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- "London's transport 'Design Icons' announced". London Transport Museum. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- Goldstein, Danielle (4 August 2015). "Transported By Design: Vote for your favourite part of London transport". Timeout.com. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Jones, Ian (6 January 2013). "76. The original platforms at Baker Street". 150 Great Things About the Underground. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- Reid, T.R. (22 September 1999). "Sherlock Holmes honored with statue near fictional London home". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Baker Street Control Room". Flickr. November 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- London Underground Junction Diagrams (PDF). London Underground. 2015. p. 2.

- "London Underground train life extension". Rail Engineer. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "TfL's Transport Portfolio Executive Report for the London 2012 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games – Quarter 2 2007/08" (PDF). TfL. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2012.

- "Accessible Transport Strategy for the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games" (PDF). London 2012. May 2008. p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2008.

- "Step-free access Baker Street station" (PDF). TfL. September 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2013.

- "Planning – Application Summary 08/08647/FULL". Westminster City Council. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013.

- "TfL sets out £9.2bn 2009/2010 budget to deliver major improvements this year" (Press release). TfL. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- "'S' stock making its mark". Modern Railways. London. December 2010. p. 46.

- "CULG – Bakerloo Line". Davros.org. Clive's UndergrounD Line Guides. 20 June 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Bakerloo Line Working Timetable No. 42" (PDF). Transport for London. 21 May 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "CULG – Jubilee Line". www.davros.org. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Jubilee line working timtable" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2017.

- "Circle and H'Smith & City line timetable" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2016.

- Simpson 2003, p. 43.

- "Watford Tube Guide" (PDF). Transport for London. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "CULG – Metropolitan Line". www.davros.org. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Day buses from Baker Street and Marylebone" (PDF). 31 August 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Night buses from Baker Street and Marylebone" (PDF). 31 August 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Betjeman, John; Games, Stephen (4 February 2010). Betjeman's England. John Murray Press. ISBN 9781848543805. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

Bibliography

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, J Graeme (1983). Steam to Silver. A history of London Transport Surface Rolling Stock. Capital Transport. ISBN 0-904711-45-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John R.; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground (10th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Demuth, Tim; Leboff, David (1999). No Need To Ask. Harrow Weald: Capital Transport. ISBN 185414-215-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Dennis; Pigram, Ron (1988). The Golden Years of the Metropolitan Railway and the Metro-land Dream. Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-870630-11-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Fowler's Ghost" (May 1962). Cooke, B.W.C (ed.). "Railway connections at King's Cross (part one)". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 108 no. 733. Tothill Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, Oliver (1987). The London Underground: An illustrated history. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1720-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2001). The Bakerloo Line: An Illustrated History. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-248-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2003). The Metropolitan Line: An Illustrated History. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-275-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2006). The District Line: An Illustrated History. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-292-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Alan (1986). London's Metropolitan Railway. David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8839-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Charles E. (1956b). The Metropolitan District Railway. The Oakwood Press. ASIN B0000CJGHS.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rose, Douglas (December 2007) [1980]. The London Underground: A Diagrammatic History (8th ed.). Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-315-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Bill (2003). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. Volume 1: The Circle and Extended Lines to Rickmansworth. Lamplight Publications. ISBN 1-899246-07-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walford, Edward (1878). New and Old London: Volume 5. British History Online. Retrieved 3 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolmar, Christian (2004). The Subterranean Railway: how the London Underground was built and how it changed the city forever. Atlantic. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baker Street tube station. |

- Oldest Portion of Baker Street Station

- "As shown in 1863". Science and Society.

- "As shown in 2004". Rail Fan Europe. (restoration) "Baker Street". Rail Fan Europe.

- "Photograph of the Jubilee line platform at Baker Street". Tube Photos.

- "Baker Street and Waterloo Railway entrance, demolished in 1964". London Transport Museum.

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

towards Harrow & Wealdstone | Bakerloo line | towards Elephant & Castle |

||

towards Hammersmith | Circle line | |||

| Hammersmith & City line | towards Barking |

|||

towards Stanmore | Jubilee line | towards Stratford |

||

| Metropolitan line | towards Aldgate |

|||

| Terminus | ||||

| Former services | ||||

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

towards Stanmore | Bakerloo line Stanmore branch (1939–1979) | towards Elephant & Castle |

||

| Metropolitan line (1868–1939) | towards Aldgate |

|||

| Terminus | ||||

towards Hammersmith | Metropolitan line Hammersmith branch (1864–1990) | towards Barking |

||