Istanbul

Istanbul (/ˌɪstænˈbʊl/,[8][9] also US: /ˈɪstænbʊl/; Turkish: İstanbul [isˈtanbuɫ] (![]()

Istanbul İstanbul | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top: the Golden Horn between Karaköy and Sarayburnu within the historic areas; Maiden's Tower; a nostalgic tram on İstiklal Avenue; Levent business district with Dolmabahçe Palace; Ortaköy Mosque in front of the Bosphorus Bridge; and Hagia Sophia. | |||||||||||||||||||

Istanbul Location within Turkey  Istanbul Location within Europe  Istanbul Location within Asia .svg.png) Istanbul Istanbul (Earth) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates: 41°00′49″N 28°57′18″E | |||||||||||||||||||

| Country | Turkey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Region | Marmara | ||||||||||||||||||

| Province | Istanbul | ||||||||||||||||||

| Provincial seat[lower-alpha 1] | Cağaloğlu, Fatih | ||||||||||||||||||

| Districts | 39 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Type | Mayor–council government | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Body | Municipal Council of Istanbul | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Mayor | Ekrem İmamoğlu (CHP) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Governor | Ali Yerlikaya | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Urban | 2,576.85 km2 (994.93 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Metro | 5,343.22 km2 (2,063.03 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 39 m (128 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population (31 December 2019)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Megacity | 15,519,267 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Rank | 1st in Turkey | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Urban | 15,214,177 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Urban density | 5,904/km2 (15,290/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Metro density | 2,904/km2 (7,520/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Istanbulite (Turkish: İstanbullu) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Postal code | 34000 to 34990 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area code(s) | 212 (European side) 216 (Asian side) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vehicle registration | 34 | ||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (Nominal) | 2018 [4][5] | ||||||||||||||||||

| - Total | US$ 244.757 billion [6] - 31.02 % of Turkey – | ||||||||||||||||||

| - Per capita | US$ 16,265 | ||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2018) | 0.828[7] (very high) · 3rd | ||||||||||||||||||

| GeoTLD | .ist, .istanbul | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | ibb www | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

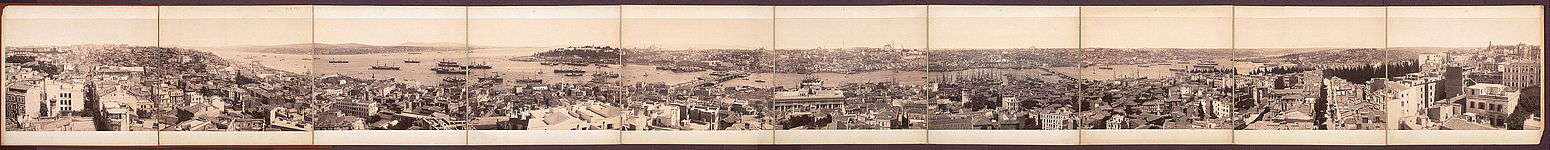

Founded under the name of Byzantion (Βυζάντιον) on the Sarayburnu promontory around 660 BCE,[11] the city grew in size and influence, becoming one of the most important cities in history. After its reestablishment as Constantinople in 330 CE,[12] it served as an imperial capital for almost sixteen centuries, during the Roman/Byzantine (330–1204), Latin (1204–1261), Byzantine (1261–1453) and Ottoman (1453–1922) empires.[13] It was instrumental in the advancement of Christianity during Roman and Byzantine times, before the Ottomans conquered the city in 1453 CE and transformed it into an Islamic stronghold and the seat of the Ottoman Caliphate.[14] Under the name Constantinople it was the Ottoman capital until 1923. The capital was then moved to Ankara and the city was renamed Istanbul.

The city held the strategic position between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. It was also on the historic Silk Road.[15] It controlled rail networks between the Balkans and the Middle East and was the only sea route between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In 1923, after the Turkish War of Independence, Ankara was chosen as the new Turkish capital, and the city's name was changed to Istanbul. Nevertheless, the city maintained its prominence in geopolitical and cultural affairs. The population of the city has increased tenfold since the 1950s, as migrants from across Anatolia have moved in and city limits have expanded to accommodate them.[16][17] Arts, music, film, and cultural festivals were established towards the end of the 20th century and continue to be hosted by the city today. Infrastructure improvements have produced a complex transportation network in the city.

Over 12 million foreign visitors came to Istanbul in 2015, five years after it was named a European Capital of Culture, making the city the world's fifth-most popular tourist destination.[18] The city's biggest attraction is its historic center, partially listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its cultural and entertainment hub is across the city's natural harbor, the Golden Horn, in the Beyoğlu district. Considered a global city,[19] it hosts the headquarters of many Turkish companies and media outlets and accounts for more than a quarter of the country's gross domestic product.[20] Hoping to capitalize on its revitalization and rapid expansion, Istanbul has bid for the Summer Olympics five times in twenty years.[21]

Toponymy

The first known name of the city is Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον, Byzántion), the name given to it at its foundation by Megarean colonists around 660 BCE.[22] The name is thought to be derived from a personal name, Byzas. Ancient Greek tradition refers to a legendary king of that name as the leader of the Greek colonists. Modern scholars have also hypothesized that the name of Byzas was of local Thracian or Illyrian origin and hence predated the Megarean settlement.[23]

After Constantine the Great made it the new eastern capital of the Roman Empire in 330 CE, the city became widely known as Constantinople, which, as the Latinized form of "Κωνσταντινούπολις" (Konstantinoúpolis), means the "City of Constantine".[22] He also attempted to promote the name "Nova Roma" and its Greek version "Νέα Ῥώμη" Nea Romē (New Rome), but this did not enter widespread usage.[24] Constantinople remained the most common name for the city in the West until the establishment of the Turkish Republic, which urged other countries to use Istanbul.[25][26] Kostantiniyye (Ottoman Turkish: قسطنطينيه), Be Makam-e Qonstantiniyyah al-Mahmiyyah (meaning "the Protected Location of Constantinople") and İstanbul were the names used alternatively by the Ottomans during their rule.[27] Although historically accurate, the use of Constantinople to refer to the city during the Ottoman period is, as of 2009, often considered by Turks to be "politically incorrect".[28]

By the 19th century, the city had acquired other names used by either foreigners or Turks. Europeans used Constantinople to refer to the whole of the city, but used the name Stamboul—as the Turks also did—to describe the walled peninsula between the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara.[28] Pera (from the Greek word for "across") was used to describe the area between the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, but Turks also used the name Beyoğlu (today the official name for one of the city's constituent districts).[29]

The name İstanbul (Turkish pronunciation: [isˈtanbuɫ] (![]()

In modern Turkish, the name is written as İstanbul, with a dotted İ, as the Turkish alphabet distinguishes between a dotted and dotless I. In English the stress is on the first or last syllable, but in Turkish it is on the second syllable (tan).[34] A person from the city is an İstanbullu (plural: İstanbullular), although Istanbulite is used in English.[35]

History

Neolithic artifacts, uncovered by archeologists at the beginning of the 21st century, indicate that Istanbul's historic peninsula was settled as far back as the 6th millennium BCE.[36] That early settlement, important in the spread of the Neolithic Revolution from the Near East to Europe, lasted for almost a millennium before being inundated by rising water levels.[37][38][39][40] The first human settlement on the Asian side, the Fikirtepe mound, is from the Copper Age period, with artifacts dating from 5500 to 3500 BCE,[41] On the European side, near the point of the peninsula (Sarayburnu), there was a Thracian settlement during the early 1st millennium BCE. Modern authors have linked it to the Thracian toponym Lygos,[42] mentioned by Pliny the Elder as an earlier name for the site of Byzantium.[43]

The history of the city proper begins around 660 BCE,[44][lower-alpha 3] when Greek settlers from Megara established Byzantium on the European side of the Bosphorus. The settlers built an acropolis adjacent to the Golden Horn on the site of the early Thracian settlements, fueling the nascent city's economy.[50] The city experienced a brief period of Persian rule at the turn of the 5th century BCE, but the Greeks recaptured it during the Greco-Persian Wars.[51] Byzantium then continued as part of the Athenian League and its successor, the Second Athenian League, before gaining independence in 355 BCE.[52] Long allied with the Romans, Byzantium officially became a part of the Roman Empire in 73 CE.[53] Byzantium's decision to side with the Roman usurper Pescennius Niger against Emperor Septimius Severus cost it dearly; by the time it surrendered at the end of 195 CE, two years of siege had left the city devastated.[54] Five years later, Severus began to rebuild Byzantium, and the city regained—and, by some accounts, surpassed—its previous prosperity.[55]

Rise and fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire

.jpg)

_by_Florentine_cartographer_Cristoforo_Buondelmonte.jpg)

Constantine the Great effectively became the emperor of the whole of the Roman Empire in September 324.[56] Two months later, he laid out the plans for a new, Christian city to replace Byzantium. As the eastern capital of the empire, the city was named Nova Roma; most called it Constantinople, a name that persisted into the 20th century.[57] On 11 May 330, Constantinople was proclaimed the capital of the Roman Empire, which was later permanently divided between the two sons of Theodosius I upon his death on 17 January 395, when the city became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.[58]

The establishment of Constantinople was one of Constantine's most lasting accomplishments, shifting Roman power eastward as the city became a center of Greek culture and Christianity.[58][59] Numerous churches were built across the city, including Hagia Sophia which was built during the reign of Justinian the Great and remained the world's largest cathedral for a thousand years.[60] Constantine also undertook a major renovation and expansion of the Hippodrome of Constantinople; accommodating tens of thousands of spectators, the hippodrome became central to civic life and, in the 5th and 6th centuries, the center of episodes of unrest, including the Nika riots.[61][62] Constantinople's location also ensured its existence would stand the test of time; for many centuries, its walls and seafront protected Europe against invaders from the east and the advance of Islam.[59] During most of the Middle Ages, the latter part of the Byzantine era, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city on the European continent and at times the largest in the world.[63][64]

Constantinople began to decline continuously after the end of the reign of Basil II in 1025. The Fourth Crusade was diverted from its purpose in 1204, and the city was sacked and pillaged by the crusaders.[65] They established the Latin Empire in place of the Orthodox Byzantine Empire.[66] Hagia Sophia was converted to a Catholic church in 1204. The Byzantine Empire was restored, albeit weakened, in 1261.[67] Constantinople's churches, defenses, and basic services were in disrepair,[68] and its population had dwindled to a hundred thousand from half a million during the 8th century.[lower-alpha 4] After the reconquest of 1261, however, some of the city's monuments were restored, and some, like the two Deisis mosaics in Hagia Sofia and Kariye, were created.

Various economic and military policies instituted by Andronikos II, such as the reduction of military forces, weakened the empire and left it vulnerable to attack.[69] In the mid-14th-century, the Ottoman Turks began a strategy of gradually taking smaller towns and cities, cutting off Constantinople's supply routes and strangling it slowly.[70] On 29 May 1453, after an eight-week siege (during which the last Roman emperor, Constantine XI, was killed), Sultan Mehmed II "the Conqueror" captured Constantinople and declared it the new capital of the Ottoman Empire. Hours later, the sultan rode to the Hagia Sophia and summoned an imam to proclaim the Islamic creed, converting the grand cathedral into an imperial mosque due to the city's refusal to surrender peacefully.[71] Mehmed declared himself as the new "Kaysar-i Rûm" (the Ottoman Turkish equivalent of Caesar of Rome) and the Ottoman state was reorganized into an empire.[72]

Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic eras

Following the conquest of Constantinople[lower-alpha 5], Mehmed II immediately set out to revitalize the city. He urged the return of those who had fled the city during the siege, and resettled Muslims, Jews, and Christians from other parts of Anatolia. He demanded that five thousand households needed to be transferred to Constantinople by September.[74] From all over the Islamic empire, prisoners of war and deported people were sent to the city: these people were called "Sürgün" in Turkish (Greek: σουργούνιδες).[75] Many people escaped again from the city, and there were several outbreaks of plague, so that in 1459 Mehmed allowed the deported Greeks to come back to the city.[76] He also invited people from all over Europe to his capital, creating a cosmopolitan society that persisted through much of the Ottoman period.[77] Plague continued to be essentially endemic in Constantinople for the rest of the century, as it had been from 1520, with a few years of respite between 1529 and 1533, 1549 and 1552, and from 1567 to 1570; epidemics originating in the West and in the Hejaz and southern Russia.[78] Population growth in Anatolia allowed Constantinople to replace its losses and maintain its population of around 500,000 inhabitants down to 1800. Mehmed II also repaired the city's damaged infrastructure, including the whole water system, began to build the Grand Bazaar, and constructed Topkapı Palace, the sultan's official residence.[79] With the transfer of the capital from Edirne (formerly Adrianople) to Constantinople, the new state was declared as the successor and continuation of the Roman Empire.[80]

_and_view_of_Pera%2C_Constantinople%2C_Turkey%2C_ca._1895.jpg)

The Ottomans quickly transformed the city from a bastion of Christianity to a symbol of Islamic culture. Religious foundations were established to fund the construction of ornate imperial mosques, often adjoined by schools, hospitals, and public baths.[79] The Ottoman Dynasty claimed the status of caliphate in 1517, with Constantinople remaining the capital of this last caliphate for four centuries.[14] Suleiman the Magnificent's reign from 1520 to 1566 was a period of especially great artistic and architectural achievement; chief architect Mimar Sinan designed several iconic buildings in the city, while Ottoman arts of ceramics, stained glass, calligraphy, and miniature flourished.[81] The population of Constantinople was 570,000 by the end of the 18th century.[82]

A period of rebellion at the start of the 19th century led to the rise of the progressive Sultan Mahmud II and eventually to the Tanzimat period, which produced political reforms and allowed new technology to be introduced to the city.[83] Bridges across the Golden Horn were constructed during this period,[84] and Constantinople was connected to the rest of the European railway network in the 1880s.[85] Modern facilities, such as a water supply network, electricity, telephones, and trams, were gradually introduced to Constantinople over the following decades, although later than to other European cities.[86] The modernization efforts were not enough to forestall the decline of the Ottoman Empire.

Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the Ottoman Parliament, closed since 14 February 1878, was reopened 30 years later on 23 July 1908, which marked the beginning of the Second Constitutional Era.[87] A series of wars in the early 20th century, such as the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), plagued the ailing empire's capital and resulted in the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état, which brought the regime of the Three Pashas.[88]

The Ottoman Empire joined World War I (1914–1918) on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The deportation of Armenian intellectuals on 24 April 1915 was among the major events which marked the start of the Armenian Genocide during WWI.[89] As a result of the war and the events in its aftermath, the city's Christian population declined from 450,000 to 240,000 between 1914 and 1927.[90] The Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918 and the Allies occupied Constantinople on 13 November 1918. The Ottoman Parliament was dissolved by the Allies on 11 April 1920 and the Ottoman delegation led by Damat Ferid Pasha was forced to sign the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920.

Following the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922, and the last Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed VI, was declared persona non-grata. Leaving aboard the British warship HMS Malaya on 17 November 1922, he went into exile and died in Sanremo, Italy, on 16 May 1926. The Treaty of Lausanne was signed on 24 July 1923, and the occupation of Constantinople ended with the departure of the last forces of the Allies from the city on 4 October 1923.[91] Turkish forces of the Ankara government, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha (3rd Corps), entered the city with a ceremony on 6 October 1923, which has been marked as the Liberation Day of Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul'un Kurtuluşu) and is commemorated every year on its anniversary.[91] On 29 October 1923 the Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the establishment of the Turkish Republic, with Ankara as its capital. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk became the Republic's first President.[92]

Ankara was selected as Turkey's capital in 1923 to distance the new, secular republic from its Ottoman history.[93] According to historian Philip Mansel:

- after the departure of the dynasty in 1925, from being the most international city in Europe, Constantinople became one of the most nationalistic....Unlike Vienna, Constantinople turned its back on the past. Even its name was changed. Constantinople was dropped because of its Ottoman and international associations. From 1926 the post office only accepted Istanbul; it appeared more Turkish and was used by most Turks.[94]

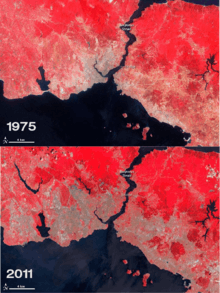

From the late 1940s and early 1950s, Istanbul underwent great structural change, as new public squares, boulevards, and avenues were constructed throughout the city, sometimes at the expense of historical buildings.[95] The population of Istanbul began to rapidly increase in the 1970s, as people from Anatolia migrated to the city to find employment in the many new factories that were built on the outskirts of the sprawling metropolis. This sudden, sharp rise in the city's population caused a large demand for housing, and many previously outlying villages and forests became engulfed into the metropolitan area of Istanbul.[96]

Geography

Istanbul is in north-western Turkey within the Marmara Region on a total area of 5,343 square kilometers (2,063 sq mi).[lower-alpha 2] The Bosphorus, which connects the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea, divides the city into a European, Thracian side—comprising the historic and economic centers—and an Asian, Anatolian side. The city is further divided by the Golden Horn, a natural harbor bounding the peninsula where the former Byzantium and Constantinople were founded. The confluence of the Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus, and the Golden Horn at the heart of present-day Istanbul has deterred attacking forces for thousands of years and remains a prominent feature of the city's landscape.[59]

Following the model of Rome, the historic peninsula is said to be characterized by seven hills, each topped by imperial mosques. The easternmost of these hills is the site of Topkapı Palace on the Sarayburnu.[101] Rising from the opposite side of the Golden Horn is another, conical hill, where the modern Beyoğlu district is. Because of the topography, buildings in Beyoğlu were once constructed with the help of terraced retaining walls, and roads were laid out in the form of steps.[102] Üsküdar on the Asian side exhibits similarly hilly characteristics, with the terrain gradually extending down to the Bosphorus coast, but the landscape in Şemsipaşa and Ayazma is more abrupt, akin to a promontory. The highest point in Istanbul is Çamlıca Hill, with an altitude of 288 meters (945 ft).[102] The northern half of Istanbul has a higher mean elevation compared to the south coast, with locations surpassing 200 meters (660 ft), and some coasts with steep cliffs resembling fjords, especially around the northern end of the Bosphorus, where it opens up to the Black Sea.

Istanbul is near the North Anatolian Fault, close to the boundary between the African and Eurasian Plates. This fault zone, which runs from northern Anatolia to the Sea of Marmara, has been responsible for several deadly earthquakes throughout the city's history. Among the most devastating of these seismic events was the 1509 earthquake, which caused a tsunami that broke over the walls of the city and killed more than 10,000 people. More recently, in 1999, an earthquake with its epicenter in nearby İzmit left 18,000 people dead, including 1,000 people in Istanbul's suburbs. The people of Istanbul remain concerned that an even more catastrophic seismic event may be in the city's near future, as thousands of structures recently built to accommodate Istanbul's rapidly increasing population may not have been constructed properly.[103] Seismologists say the risk of a 7.6-magnitude or greater earthquake striking Istanbul by 2030 is more than 60 percent.[104][105]

Climate

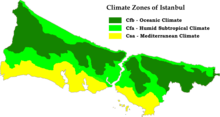

In the Köppen–Geiger classification system, Istanbul has a borderline Mediterranean climate (Csa), humid subtropical climate (Cfa) and oceanic climate (Cfb), due to its location in a transitional climatic zone. Since precipitation in summer months ranges from 20 to 65 mm (1 to 3 in), depending on location, the city cannot be classified as solely Mediterranean or humid subtropical.[106][107][108] Due to its size, diverse topography, maritime location and most importantly having a coastline to two different bodies of water to the north and south, Istanbul exhibits microclimates. The northern half of the city, as well as the Bosporus coastline, express characteristics of oceanic and humid subtropical climates, because of humidity from the Black Sea and the relatively high concentration of vegetation. The climate in the populated areas of the city to the south, on the Sea of Marmara, is warmer, drier and less affected by humidity.[109] The annual precipitation in the northern half can be twice as much (Bahçeköy, 1166.6 mm), than it is in the southern, Marmara coast (Florya 635.0 mm).[110] There is a significant difference between annual mean temperatures on the north and south coasts as well, Bahçeköy 12.8 °C (55.0 °F), Kartal 15.03 °C (59.05 °F).[111] Parts of the province that are away from both seas exhibit considerable continental influences, with much more pronounced night-day and summer-winter temperature differences. In winter some parts of the province average freezing or below at night.

Istanbul's persistently high humidity reaches 80 percent most mornings.[112] Because of this, fog is very common, although more so in northern parts of the city and away from the city center.[109] Dense fog disrupts transportation in the region, including on the Bosphorus, and is common during the autumn and winter months when the humidity remains high into the afternoon.[113][114][115] The humid conditions and the fog tend to dissipate by midday during the summer months, but the lingering humidity exacerbates the moderately high summer temperatures.[112][116] During these summer months, high temperatures average around 29 °C (84 °F) and rainfall is uncommon; there are only about fifteen days with measurable precipitation between June and August.[117] The summer months also have the highest concentration of thunderstorms.[118]

Winter is colder in Istanbul than in most other cities around the Mediterranean Basin, with low temperatures averaging 1–4 °C (34–39 °F).[117] Lake-effect snow from the Black Sea is common, although difficult to forecast, with the potential to be heavy and—as with the fog—disruptive to the city's infrastructure.[119] Spring and autumn are mild, but often wet and unpredictable; chilly winds from the northwest and warm gusts from the south—sometimes in the same day—tend to cause fluctuations in temperature.[116][120] Overall, Istanbul has an annual average of 130 days with significant precipitation, which amounts to 810 millimeters (31.9 in) per year.[117][121] The highest and lowest temperatures ever recorded in the city center on the Marmara coast are 40.5 °C (105 °F) and −16.1 °C (3 °F). The greatest rainfall recorded in a day is 227 millimeters (8.9 in), and the highest recorded snow cover is 80 centimeters (31 in).[122][123]

| Climate data for Istanbul (Sarıyer), 1929–2017 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.5 (94.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

41.5 (106.7) |

40.5 (104.9) |

39.5 (103.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

41.5 (106.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.9 (7.0) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 106.0 (4.17) |

77.7 (3.06) |

71.4 (2.81) |

45.9 (1.81) |

34.4 (1.35) |

36.0 (1.42) |

33.3 (1.31) |

39.9 (1.57) |

61.7 (2.43) |

88.0 (3.46) |

100.9 (3.97) |

122.2 (4.81) |

817.4 (32.18) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 17.3 | 15.2 | 13.8 | 10.3 | 8.0 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 17.1 | 129.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.9 | 101.7 | 142.6 | 195.0 | 272.8 | 318.0 | 356.5 | 328.6 | 246.0 | 176.7 | 120.0 | 83.7 | 2,431.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.9 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 8.8 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 8.2 | 5.7 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 6.6 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source: Turkish State Meteorological Service[124] and Weather Atlas[125] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Istanbul (Kireçburnu, Sarıyer), 1949–1999 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.5 (41.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

13.7 (56.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.7 (51.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 103.6 (4.08) |

70.5 (2.78) |

71.0 (2.80) |

47.2 (1.86) |

45.8 (1.80) |

36.8 (1.45) |

35.6 (1.40) |

38.6 (1.52) |

51.9 (2.04) |

81.3 (3.20) |

100.8 (3.97) |

122.0 (4.80) |

805.1 (31.7) |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 3.6 | 4.9 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 13.1 |

| Source: Turkish State Meteorological Service[126] (1949–1999) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Istanbul (Bahçeköy, Sarıyer), 1949–1999 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

17.4 (63.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 152.1 (5.99) |

100.1 (3.94) |

105.2 (4.14) |

57.2 (2.25) |

45.8 (1.80) |

40.5 (1.59) |

37.4 (1.47) |

54.1 (2.13) |

67.3 (2.65) |

118.2 (4.65) |

135.1 (5.32) |

175.4 (6.91) |

1,088.4 (42.84) |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 4.6 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 17.3 |

| Source: Turkish State Meteorological Service[127] (1949–1999) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Istanbul | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.5 (60.0) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [125] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

Global warming in Turkey may cause more urban heatwaves,[128] droughts,[129] storms,[130] and flooding.[131][132] Sea level rise is forecast to affect city infrastructure, for example Kadıkoy metro station is threatened with flooding.[133] Xeriscaping of green spaces has been suggested,[134] and Istanbul has a climate-change action plan.[135]

Cityscape

The Fatih district, which was named after Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (Turkish: Fatih Sultan Mehmed), corresponds to what was, until the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the whole of the city of Constantinople (today is the capital district and called the historic peninsula of Istanbul) on the southern shore of the Golden Horn, across the medieval Genoese citadel of Galata on the northern shore. The Genoese fortifications in Galata were largely demolished in the 19th century, leaving only the Galata Tower, to make way for the northward expansion of the city.[136] Galata (Karaköy) is today a quarter within the Beyoğlu (Pera) district, which forms Istanbul's commercial and entertainment center and includes İstiklal Avenue and Taksim Square.[137]

Dolmabahçe Palace, the seat of government during the late Ottoman period, is in the Beşiktaş district on the European shore of the Bosphorus strait, to the north of Beyoğlu. The Sublime Porte (Bâb-ı Âli), which became a metonym for the Ottoman government, was originally used to describe the Imperial Gate (Bâb-ı Hümâyûn) at the outermost courtyard of the Topkapı Palace; but after the 18th century, the Sublime Porte (or simply Porte) began to refer to the gate of the Sadrazamlık (Prime Ministry) compound in the Cağaloğlu quarter near Topkapı Palace, where the offices of the Sadrazam (Grand Vizier) and other Viziers were, and where foreign diplomats were received. The former village of Ortaköy is within Beşiktaş and gives its name to the Ortaköy Mosque on the Bosphorus, near the Bosphorus Bridge. Lining both the European and Asian shores of the Bosphorus are the historic yalıs, luxurious chalet mansions built by Ottoman aristocrats and elites as summer homes.[138] Farther inland, outside the city's inner ring road, are Levent and Maslak, Istanbul's main business districts.[139]

During the Ottoman period, Üsküdar (then Scutari) and Kadıköy were outside the scope of the urban area, serving as tranquil outposts with seaside yalıs and gardens. But in the second half of the 20th century, the Asian side experienced major urban growth; the late development of this part of the city led to better infrastructure and tidier urban planning when compared with most other residential areas in the city.[10] Much of the Asian side of the Bosphorus functions as a suburb of the economic and commercial centers in European Istanbul, accounting for a third of the city's population but only a quarter of its employment.[10] As a result of Istanbul's exponential growth in the 20th century, a significant portion of the city is composed of gecekondus (literally "built overnight"), referring to illegally constructed squatter buildings.[140] At present, some gecekondu areas are being gradually demolished and replaced by modern mass-housing compounds.[141] Moreover, large scale gentrification and urban renewal projects have been taking place,[142] such as the one in Tarlabaşı;[143] some of these projects, like the one in Sulukule, have faced criticism.[144] The Turkish government also has ambitious plans for an expansion of the city west and northwards on the European side in conjunction with plans for a third airport; the new parts of the city will include four different settlements with specified urban functions, housing 1.5 million people.[145]

Istanbul does not have a primary urban park, but it has several green areas. Gülhane Park and Yıldız Park were originally included within the grounds of two of Istanbul's palaces—Topkapı Palace and Yıldız Palace—but they were repurposed as public parks in the early decades of the Turkish Republic.[146] Another park, Fethi Paşa Korusu, is on a hillside adjacent to the Bosphorus Bridge in Anatolia, opposite Yıldız Palace in Europe. Along the European side, and close to the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, is Emirgan Park, which was known as the Kyparades (Cypress Forest) during the Byzantine period. In the Ottoman period, it was first granted to Nişancı Feridun Ahmed Bey in the 16th century, before being granted by Sultan Murad IV to the Safavid Emir Gûne Han in the 17th century, hence the name Emirgan. The 47-hectare (120-acre) park was later owned by Khedive Ismail Pasha of Ottoman Egypt and Sudan in the 19th century. Emirgan Park is known for its diversity of plants and an annual tulip festival is held there since 2005.[147] The AKP government's decision to replace Taksim Gezi Park with a replica of the Ottoman era Taksim Military Barracks (which was transformed into the Taksim Stadium in 1921, before being demolished in 1940 for building Gezi Park) sparked a series of nationwide protests in 2013 covering a wide range of issues. Popular during the summer among Istanbulites is Belgrad Forest, spreading across 5,500 hectares (14,000 acres) at the northern edge of the city. The forest originally supplied water to the city and remnants of reservoirs used during Byzantine and Ottoman times survive.[148][149]

Edge cities (office and retail districts)

Modern shopping malls, dense residential and hotel towers, and entertainment, educational and other facilities can be found outside the historic center in the following edge cities:[150]

- Taksim-Beyoğlu: Taksim Square in Beyoğlu to Nişantaşı in Şişli[150]

- The Central Business District as the real estate industry refers to it, which is not the historic city center, but is a 7-km-long north–south corridor of modern areas along Barbaros Boulevard and Büyükdere Avenue. Metro Line 2 runs along part of it. From south to north, the areas in the corridor are:[150]

- in Beşiktaş district:

- Balmumcu

- Gayrettepe incl. Profilo, Astoria and Trump Towers (Trump Alışveriş Merkezi) complexes

- Etiler including Boğaziçi University

- in Şişli district:

- Fulya, Otim and the core Şişli neighborhood incl. the İstanbul Cevahir complex

- Esentepe including Zincirlikuyu and the Zorlu Center complex

- Levent including the Metrocity, Özdilekpark, Kanyon and Istanbul Sapphire complexes

- in Sarıyer district:

- Maslak including the İstinye Park complex and the Istanbul Technical University

- the Vadistanbul mall and office complexes in Ayazağa

- in Beşiktaş district:

- Istanbul Atatürk Airport area: strip development along the O-7 highway north to the Mall of Istanbul, Bahçelievler district[150]

- Asian side:

Architecture

Istanbul is primarily known for its Byzantine and Ottoman architecture, but its buildings reflect the various peoples and empires that have previously ruled the city. Examples of Genoese and Roman architecture remain visible in Istanbul alongside their Ottoman counterparts. Nothing of the architecture of the classical Greek period has survived, but Roman architecture has proved to be more durable. The obelisk erected by Theodosius in the Hippodrome of Constantinople is still visible in Sultanahmet Square, and a section of the Valens Aqueduct, constructed in the late 4th century, stands relatively intact at the western edge of the Fatih district.[152] The Column of Constantine, erected in 330 CE to mark the new Roman capital, stands not far from the Hippodrome.[152]

Early Byzantine architecture followed the classical Roman model of domes and arches, but improved upon these elements, as in the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus. The oldest surviving Byzantine church in Istanbul—albeit in ruins—is the Monastery of Stoudios (later converted into the Imrahor Mosque), which was built in 454.[154] After the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantines enlarged two of the most important churches extant, Chora Church and Pammakaristos Church. The pinnacle of Byzantine architecture, and one of Istanbul's most iconic structures, is the Hagia Sophia. Topped by a dome 31 meters (102 ft) in diameter,[155] the Hagia Sophia stood as the world's largest cathedral for centuries, and was later converted into a mosque and, as it stands now, a museum.[60]

Among the oldest surviving examples of Ottoman architecture in Istanbul are the Anadoluhisarı and Rumelihisarı fortresses, which assisted the Ottomans during their siege of the city.[156] Over the next four centuries, the Ottomans made an indelible impression on the skyline of Istanbul, building towering mosques and ornate palaces. The largest palace, Topkapı, includes a diverse array of architectural styles, from Baroque inside the Harem, to its Neoclassical style Enderûn Library.[157] The imperial mosques include Fatih Mosque, Bayezid Mosque, Yavuz Selim Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, Sultan Ahmed Mosque (the Blue Mosque), and Yeni Mosque, all of which were built at the peak of the Ottoman Empire, in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the following centuries, and especially after the Tanzimat reforms, Ottoman architecture was supplanted by European styles.[158] An example of which is the imperial Nuruosmaniye Mosque. Areas around İstiklal Avenue were filled with grand European embassies and rows of buildings in Neoclassical, Renaissance Revival and Art Nouveau styles, which went on to influence the architecture of a variety of structures in Beyoğlu—including churches, stores, and theaters—and official buildings such as Dolmabahçe Palace.[159]

Administration

Since 2004, the municipal boundaries of Istanbul have been coincident with the boundaries of its province.[160] The city, considered capital of Istanbul Province, is administered by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (MMI), which oversees the 39 districts of the city-province.[lower-alpha 2]

The current city structure can be traced back to the Tanzimat period of reform in the 19th century, before which Islamic judges and imams led the city under the auspices of the Grand Vizier. Following the model of French cities, this religious system was replaced by a mayor and a citywide council composed of representatives of the confessional groups (millet) across the city. Pera (now Beyoğlu) was the first area of the city to have its own director and council, with members instead being longtime residents of the neighborhood.[161] Laws enacted after the Ottoman constitution of 1876 aimed to expand this structure across the city, imitating the twenty arrondissements of Paris, but they were not fully implemented until 1908, when the city was declared a province with nine constituent districts.[162][163] This system continued beyond the founding of the Turkish Republic, with the province renamed a belediye (municipality), but the municipality was disbanded in 1957.[98][164]

Small settlements adjacent to major population centers in Turkey, including Istanbul, were merged into their respective primary cities during the early 1980s, resulting in metropolitan municipalities.[165][166] The main decision-making body of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality is the Municipal Council, with members drawn from district councils.

The Municipal Council is responsible for citywide issues, including managing the budget, maintaining civic infrastructure, and overseeing museums and major cultural centers.[167] Since the government operates under a "powerful mayor, weak council" approach, the council's leader—the metropolitan mayor—has the authority to make swift decisions, often at the expense of transparency.[168] The Municipal Council is advised by the Metropolitan Executive Committee, although the committee also has limited power to make decisions of its own.[169] All representatives on the committee are appointed by the metropolitan mayor and the council, with the mayor—or someone of his or her choosing—serving as head.[169][170]

District councils are chiefly responsible for waste management and construction projects within their respective districts. They each maintain their own budgets, although the metropolitan mayor reserves the right to review district decisions. One-fifth of all district council members, including the district mayors, also represent their districts in the Municipal Council.[167] All members of the district councils and the Municipal Council, including the metropolitan mayor, are elected to five-year terms.[171] Representing the Republican People's Party, Ekrem İmamoğlu has been the Mayor of Istanbul since 23 June 2019.[172]

With the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and Istanbul Province having equivalent jurisdictions, few responsibilities remain for the provincial government. Similar to the MMI, the Istanbul Special Provincial Administration has a governor, a democratically elected decision-making body—the Provincial Parliament—and an appointed Executive Committee. Mirroring the executive committee at the municipal level, the Provincial Executive Committee includes a secretary-general and leaders of departments that advise the Provincial Parliament.[170][173] The Provincial Administration's duties are largely limited to the building and maintenance of schools, residences, government buildings, and roads, and the promotion of arts, culture, and nature conservation.[174] Vasip Şahin has been the Governor of Istanbul Province since 25 September 2014.[175]

Demographics

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Jan Lahmeyer 2004,Chandler 1987, Morris 2010,Turan 2010 Pre-Republic figures estimated[lower-alpha 4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Throughout most of its history, Istanbul has ranked among the largest cities in the world. By 500 CE, Constantinople had somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 people, edging out its predecessor, Rome, for world's largest city.[177] Constantinople jostled with other major historical cities, such as Baghdad, Chang'an, Kaifeng and Merv for the position of world's most populous city until the 12th century. It never returned to being the world's largest, but remained Europe's largest city from 1500 to 1750, when it was surpassed by London.[178]

The Turkish Statistical Institute estimates that the population of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality was 14,377,019 at the end of 2014, hosting 19 percent of the country's population.[3] Then about 97–98% of the inhabitants of the metropolitan municipality were within city limits, up from 89% in 2007[179] and 61% in 1980.[180] 64.9% of the residents live on the European side and 35.1% on the Asian side.[181] While the city ranks as the world's 5th-largest city proper, it drops to the 24th place as an urban area and to the 18th place as a metro area because the city limits are roughly equivalent to the agglomeration. Today, it forms one of the largest urban agglomerations in Europe, alongside Moscow.[lower-alpha 6] The city's annual population growth of 3.45 percent ranks as the highest among the seventy-eight largest metropolises in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The high population growth mirrors an urbanization trend across the country, as the second and third fastest-growing OECD metropolises are the Turkish cities of İzmir and Ankara.[20]

Istanbul experienced especially rapid growth during the second half of the 20th century, with its population increasing tenfold between 1950 and 2000.[16] This growth in population comes, in part, from an expansion of city limits—particularly between 1980 and 1985, when the number of Istanbulites nearly doubled.[98] The remarkable growth was, and still is, largely fueled by migrants from eastern Turkey seeking employment and improved living conditions. The number of residents of Istanbul originating from seven northern and eastern provinces is greater than the populations of their entire respective provinces; Sivas and Kastamonu each account for more than half a million residents of Istanbul.[17] Istanbul's foreign population, by comparison, is very small, 42,228 residents in 2007.[184] Only 28 percent of the city's residents are originally from Istanbul.[185] The most densely populated areas tend to lie to the northwest, west, and southwest of the city center, on the European side; the most densely populated district on the Asian side is Üsküdar.[17]

Religious and ethnic groups

Istanbul has been a cosmopolitan city throughout much of its history, but it has become more homogenized since the end of the Ottoman Empire. The vast majority of people across Turkey, and in Istanbul, are Muslim, and more specifically members of the Sunni branch of Islam. Most Sunni Turks follow the Hanafi school of Islamic thought, while Sunni Kurds tend to follow the Shafi'i school. The largest non-Sunni Muslim group, accounting 10–20% of Turkey's population[186], are the Alevis; a third of all Alevis in the country live in Istanbul.[185] Mystic movements, like Sufism, were officially banned after the establishment of the Turkish Republic, but they still boast numerous followers.[187] Istanbul is a migrant city. Since the 1950s, Istanbul's population has increased from 1 million to about 10 million residents. Almost 200,000 new immigrants, many of them from Turkey's own villages, continue to arrive each year. As a result, the city constant change, constantly reshaped to achieve the needs of these new population.[188]

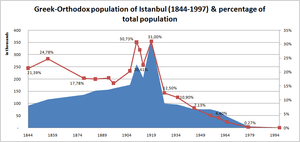

The Patriarch of Constantinople has been designated Ecumenical Patriarch since the sixth century, and has come to be regarded as the leader of the world's 300 million Orthodox Christians.[189] Since 1601, the Patriarchate has been based in Istanbul's Church of St. George.[190] Into the 19th century, the Christians of Istanbul tended to be either Greek Orthodox, members of the Armenian Apostolic Church or Catholic Levantines.[191] Because of events during the 20th century—including the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey, a 1942 wealth tax, and the 1955 Istanbul riots—the Greek population, originally centered in Fener and Samatya, has decreased substantially. At the start of the 21st century, Istanbul's Greek population numbered 3,000 (down from 260,000 out of 850,000 according to the Ottoman Census of 1910, and a peak of 350,000 in 1919).[192][193] There are today between 50,000 and 90,000 Armenians in Istanbul, down from about 164,000 according to the Ottoman Census of 1913 (partly due to the Armenian Genocide).[194] The Levantines, Latin Christians who settled in Galata during the Ottoman period, played a seminal role in shaping the culture and architecture of Istanbul during the 19th and early 20th centuries; their population has dwindled, but they remain in the city in small numbers.[195]

The largest ethnic minority in Istanbul is the Kurdish community, originating from eastern and southeastern Turkey. Although the Kurdish presence in the city dates back to the early Ottoman period,[196] the influx of Kurds into the city has accelerated since the beginning of the Kurdish–Turkish conflict in the late 1970s.[197] Between two and four million residents of Istanbul are Kurdish, meaning there are more Kurds in Istanbul than in any other city in the world.[198] There are other significant ethnic minorities as well, the Bosniaks are the main people of an entire district – Bayrampaşa.[199] The neighborhood of Balat used to be home to a sizable Sephardi Jewish community, first formed after their expulsion from Spain in 1492.[200] Romaniotes and Ashkenazi Jews resided in Istanbul even before the Sephardim, but their proportion has since dwindled; today, 1 percent of Istanbul's Jews are Ashkenazi.[201][202] In large part due to emigration to Israel, the Jewish population nationwide dropped from 100,000 in 1950 to 18,000 in 2005, with the majority of them living in either Istanbul or İzmir.[203] From the increase in mutual cooperation between Turkey and several African States like Somalia and Djibouti, several young students and workers have been migrating to Istanbul in search of better education and employment opportunities. There are Nigerian, Congolese and Cameroonian communities present.[204]

Politics

İstanbul district Municipalities 2019 Turkish local elections | |

|---|---|

| AK Party (People's Alliance) | 24 / 39

|

| CHP (Nation Alliance) | 14 / 39

|

| MHP (People's Alliance) | 1 / 39

|

Members of Parliament for İstanbul Turkish parliamentary election, 2018 | |

|---|---|

| AK Party (People's Alliance) | 43 / 98

|

| CHP (Nation Alliance) | 27 / 98

|

| HDP (No alliance) | 12 / 98

|

| İYİ (Nation Alliance) | 8 / 98

|

| MHP (People's Alliance) | 8 / 98

|

Politically, Istanbul is seen as the most important administrative region in Turkey. Many politicians, including the President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, are of the view that a political party's performance in Istanbul is more significant than its general performance overall. This is due to the city's role as Turkey's financial center, its large electorate and the fact that Erdoğan himself was elected Mayor of Istanbul in 1994. In the run-up to local elections in 2019, Erdoğan claimed 'if we fail in Istanbul, we will fail in Turkey'.[205]

Historically, Istanbul has voted for the winning party in general elections since 1995. Since 2002, the right-wing Justice and Development Party (AKP) has won pluralities in every general election, with 41.74% of the vote in the most recent parliamentary election on 24 June 2018. Erdoğan, the AKP's presidential candidate, received exactly 50.0% of the vote in the presidential election held on the same day. Starting with Erdoğan in 1994, Istanbul has had a conservative mayor for 25 years, until 2019. The second largest party in Istanbul is the center-left Republican People's Party (CHP), which is also the country's main opposition. The left-wing pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) is the city's third largest political force due to a substantial number of Kurdish people migrating from south-eastern Turkey.

More recently, Istanbul and many of Turkey's metropolitan cities are following a trend away from the government and their right-wing ideology. In 2013 and 2014, large-scale anti-AKP government protests began in İstanbul and spread throughout the nation. This trend first became evident electorally in the 2014 mayoral election where the center-left opposition candidate won an impressive 40% of the vote, despite not winning. The first government defeat in Istanbul occurred in the 2017 constitutional referendum, where Istanbul voted 'No' by 51.4% to 48.6%. The AKP government had supported a 'Yes' vote and won the vote nationally due to high support in rural parts of the country. The biggest defeat for the government came in the 2019 local elections, where their candidate for Mayor, former Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım, was defeated by a very narrow margin by the opposition candidate Ekrem İmamoğlu. İmamoğlu won the vote with 48.77% of the vote, against Yıldırım's 48.61%. Similar trends and electoral successes for the opposition were also replicated in Ankara, Izmir, Antalya, Mersin, Adana and other metropolitan areas of Turkey.

Administratively, Istanbul is divided into 39 districts, more than any other province in Turkey. As a province, Istanbul sends 98 Members of Parliament to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, which has a total of 600 seats. For the purpose of parliamentary elections, Istanbul is divided into three electoral districts; two on the European side and one on the Asian side, electing 28, 35 and 35 MPs respectively.

Economy

With a PPP-adjusted gross domestic product of US$301.1 billion, Istanbul ranked 29th among the world's urban areas in 2011.[206] Since the mid-1990s, Istanbul's economy has been one of the fastest-growing among OECD metro-regions.[20] Istanbul is responsible for 27 percent of Turkey's GDP, with 20 percent of the country's industrial labor force residing in the city.[20][207] Its GDP per capita and productivity are greater than their national averages by 70 percent and 50 percent, respectively, owing in part to the focus on high-value-added activities. With its high population and significant contribution to the Turkish economy, Istanbul is responsible for two-fifths of the nation's tax revenue.[20] That includes the taxes of 37 US-dollar billionaires based in Istanbul, the fifth-highest number among cities around the world.[208]

As expected for a city of its size, Istanbul has a diverse industrial economy, producing commodities as varied as olive oil, tobacco, vehicles, and electronics.[207] Despite having a focus on high-value-added work, its low-value-added manufacturing sector is substantial, representing just 26 percent of Istanbul's GDP, but four-fifths of the city's total exports.[20] In 2005, companies based in Istanbul produced exports worth $41.4 billion and received imports totaling $69.9 billion; these figures were equivalent to 57 percent and 60 percent, respectively, of the national totals.[209]

Istanbul is home to Borsa Istanbul, the sole exchange entity of Turkey, which combined the former Istanbul Stock Exchange, the Istanbul Gold Exchange, and the Derivatives Exchange of Turkey.[210] The former Istanbul Stock Exchange was originally established as the Ottoman Stock Exchange in 1866.[211] During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Bankalar Caddesi (Banks Street) in Galata was the financial center of the Ottoman Empire, where the Ottoman Stock Exchange was located.[212] Bankalar Caddesi continued to be Istanbul's main financial district until the 1990s, when most Turkish banks began moving their headquarters to the modern central business districts of Levent and Maslak. In 1995, the Istanbul Stock Exchange (now Borsa Istanbul) moved to its current building in the İstinye quarter of the Sarıyer district.[213] A new central business district is also under construction in Ataşehir and will host the headquarters of various Turkish banks and financial institutions upon completion.[214]

As the only sea route between the oil-rich Black Sea and the Mediterranean, the Bosphorus is one of the busiest waterways in the world; more than 200 million tonnes of oil pass through the strait each year, and the traffic on the Bosphorus is three times that on the Suez Canal.[215] As a result, there have been proposals to build a canal, known as Canal Istanbul, parallel to the strait, on the European side of the city.[216] Istanbul has three major shipping ports—the Port of Haydarpaşa, the Port of Ambarlı, and the Port of Zeytinburnu—as well as several smaller ports and oil terminals along the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara.[217][218] Haydarpaşa, at the southeastern end of the Bosphorus, was Istanbul's largest port until the early 2000s. Shifts in operations to Ambarlı since then have left Haydarpaşa running under capacity and with plans to decommission the port.[219] In 2007, Ambarlı, on the western edge of the urban center, had an annual capacity of 1.5 million TEUs (compared to 354,000 TEUs at Haydarpaşa), making it the fourth-largest cargo terminal in the Mediterranean basin.[220][221] The Port of Zeytinburnu is advantaged by its proximity to motorways and Atatürk International Airport,[222] and long-term plans for the city call for greater connectivity between all terminals and the road and rail networks.[223]

Istanbul is an increasingly popular tourist destination; whereas just 2.4 million foreigners visited the city in 2000, it welcomed 12.56 million foreign tourists in 2015, making it the world's fifth most-visited city.[18][224] Istanbul is Turkey's second-largest international gateway, after Antalya, receiving a quarter of the nation's foreign tourists. Istanbul's tourist industry is concentrated in the European side, with 90 percent of the city's hotels there. Low- and mid-range hotels tend to be on the Sarayburnu; higher-end hotels are primarily in the entertainment and financial centers north of the Golden Horn. Istanbul's seventy museums, the most visited of which are the Topkapı Palace Museum and the Hagia Sophia, bring in $30 million in revenue each year. The city's environmental master plan also notes that there are 17 palaces, 64 mosques, and 49 churches of historical significance in Istanbul.[225]

Culture

Istanbul was historically known as a cultural hub, but its cultural scene stagnated after the Turkish Republic shifted its focus toward Ankara.[227] The new national government established programs that served to orient Turks toward musical traditions, especially those originating in Europe, but musical institutions and visits by foreign classical artists were primarily centered in the new capital.[228] Much of Turkey's cultural scene had its roots in Istanbul, and by the 1980s and 1990s Istanbul reemerged globally as a city whose cultural significance is not solely based on its past glory.[229]

By the end of the 19th century, Istanbul had established itself as a regional artistic center, with Turkish, European, and Middle Eastern artists flocking to the city. Despite efforts to make Ankara Turkey's cultural heart, Istanbul had the country's primary institution of art until the 1970s.[230] When additional universities and art journals were founded in Istanbul during the 1980s, artists formerly based in Ankara moved in.[231] Beyoğlu has been transformed into the artistic center of the city, with young artists and older Turkish artists formerly residing abroad finding footing there. Modern art museums, including İstanbul Modern, the Pera Museum, Sakıp Sabancı Museum and SantralIstanbul, opened in the 2000s to complement the exhibition spaces and auction houses that have already contributed to the cosmopolitan nature of the city.[232] These museums have yet to attain the popularity of older museums on the historic peninsula, including the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, which ushered in the era of modern museums in Turkey, and the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum.[225][226]

The first film screening in Turkey was at Yıldız Palace in 1896, a year after the technology publicly debuted in Paris.[237] Movie theaters rapidly cropped up in Beyoğlu, with the greatest concentration of theaters being along the street now known as İstiklal Avenue.[238] Istanbul also became the heart of Turkey's nascent film industry, although Turkish films were not consistently developed until the 1950s.[239] Since then, Istanbul has been the most popular location to film Turkish dramas and comedies.[240] The Turkish film industry ramped up in the second half of the century, and with Uzak (2002) and My Father and My Son (2005), both filmed in Istanbul, the nation's movies began to see substantial international success.[241] Istanbul and its picturesque skyline have also served as a backdrop for several foreign films, including From Russia with Love (1963), Topkapi (1964), The World Is Not Enough (1999), and Mission Istaanbul (2008).[242]

Coinciding with this cultural reemergence was the establishment of the Istanbul Festival, which began showcasing a variety of art from Turkey and around the world in 1973. From this flagship festival came the International Istanbul Film Festival and the Istanbul International Jazz Festival in the early 1980s. With its focus now solely on music and dance, the Istanbul Festival has been known as the Istanbul International Music Festival since 1994.[243] The most prominent of the festivals that evolved from the original Istanbul Festival is the Istanbul Biennial, held every two years since 1987. Its early incarnations were aimed at showcasing Turkish visual art, and it has since opened to international artists and risen in prestige to join the elite biennales, alongside the Venice Biennale and the São Paulo Art Biennial.[244]

Leisure and entertainment

Istanbul has numerous shopping centers, from the historic to the modern. The Grand Bazaar, in operation since 1461, is among the world's oldest and largest covered markets.[245][246] Mahmutpasha Bazaar is an open-air market extending between the Grand Bazaar and the Egyptian Bazaar, which has been Istanbul's major spice market since 1660. Galleria Ataköy ushered in the age of modern shopping malls in Turkey when it opened in 1987.[247] Since then, malls have become major shopping centers outside the historic peninsula. Akmerkez was awarded the titles of "Europe's best" and "World's best" shopping mall by the International Council of Shopping Centers in 1995 and 1996; Istanbul Cevahir has been one of the continent's largest since opening in 2005; Kanyon won the Cityscape Architectural Review Award in the Commercial Built category in 2006.[246] İstinye Park in İstinye and Zorlu Center near Levent are among the newest malls which include the stores of the world's top fashion brands. Abdi İpekçi Street in Nişantaşı and Bağdat Avenue on the Anatolian side of the city have evolved into high-end shopping districts.[248][249]

Istanbul is known for its historic seafood restaurants. Many of the city's most popular and upscale seafood restaurants line the shores of the Bosphorus (particularly in neighborhoods like Ortaköy, Bebek, Arnavutköy, Yeniköy, Beylerbeyi and Çengelköy). Kumkapı along the Sea of Marmara has a pedestrian zone that hosts around fifty fish restaurants.[250] The Princes' Islands, 15 kilometers (9 mi) from the city center, are also popular for their seafood restaurants. Because of their restaurants, historic summer mansions, and tranquil, car-free streets, the Prince Islands are a popular vacation destination among Istanbulites and foreign tourists.[251] Istanbul is also famous for its sophisticated and elaborately-cooked dishes of the Ottoman cuisine. Following the influx of immigrants from southeastern and eastern Turkey, which began in the 1960s, the foodscape of the city has drastically changed by the end of the century; with influences of Middle Eastern cuisine such as kebab taking an important place in the food scene. Restaurants featuring foreign cuisines are mainly concentrated in the Beyoğlu, Beşiktaş, Şişli, and Kadıköy districts.

Istanbul has active nightlife and historic taverns, a signature characteristic of the city for centuries if not millennia. Along İstiklal Avenue is the Çiçek Pasajı, now home to winehouses (known as meyhanes), pubs, and restaurants.[252] İstiklal Avenue, originally known for its taverns, has shifted toward shopping, but the nearby Nevizade Street is still lined with winehouses and pubs.[253][254] Some other neighborhoods around İstiklal Avenue have been revamped to cater to Beyoğlu's nightlife, with formerly commercial streets now lined with pubs, cafes, and restaurants playing live music.[255] Other focal points for Istanbul's nightlife include Nişantaşı, Ortaköy, Bebek, and Kadıköy.[256]

Sports

Istanbul is home to some of Turkey's oldest sports clubs. Beşiktaş JK, established in 1903, is considered the oldest of these sports clubs. Due to its initial status as Turkey's only club, Beşiktaş occasionally represented the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic in international sports competitions, earning the right to place the Turkish flag inside its team logo.[257] Galatasaray SK and Fenerbahçe SK have fared better in international competitions and have won more Süper Lig titles, at 22 and 19 times, respectively.[258][259][260] Galatasaray and Fenerbahçe have a long-standing rivalry, with Galatasaray based in the European part and Fenerbahçe based in the Anatolian part of the city.[259] Istanbul has seven basketball teams—Anadolu Efes, Beşiktaş, Darüşşafaka, Fenerbahçe, Galatasaray, İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyespor and Büyükçekmece—that play in the premier-level Turkish Basketball Super League.[261]

Many of Istanbul's sports facilities have been built or upgraded since 2000 to bolster the city's bids for the Summer Olympic Games. Atatürk Olympic Stadium, the largest multi-purpose stadium in Turkey, was completed in 2002 as an IAAF first-class venue for track and field.[262] The stadium hosted the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final and will host the 2020 UEFA Champions League Final.[263] Şükrü Saracoğlu Stadium, Fenerbahçe's home field, hosted the 2009 UEFA Cup Final three years after its completion. Türk Telekom Arena opened in 2011 to replace Ali Sami Yen Stadium as Galatasaray's home turf,[264][265] while Vodafone Park, opened in 2016 to replace BJK İnönü Stadium as the home turf of Beşiktaş, hosted the 2019 UEFA Super Cup game. All four stadiums are elite Category 4 (formerly five-star) UEFA stadiums.[lower-alpha 7]

2. Ülker Sports Arena

The Sinan Erdem Dome, among the largest indoor arenas in Europe, hosted the final of the 2010 FIBA World Championship, the 2012 IAAF World Indoor Championships, as well as the 2011–12 Euroleague and 2016–17 EuroLeague Final Fours.[269] Prior to the completion of the Sinan Erdem Dome in 2010, Abdi İpekçi Arena was Istanbul's primary indoor arena, having hosted the finals of EuroBasket 2001.[270] Several other indoor arenas, including the Beşiktaş Akatlar Arena, have also been inaugurated since 2000, serving as the home courts of Istanbul's sports clubs. The most recent of these is the 13,800-seat Ülker Sports Arena, which opened in 2012 as the home court of Fenerbahçe's basketball teams.[271] Despite the construction boom, five bids for the Summer Olympics—in 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2020—and national bids for UEFA Euro 2012 and UEFA Euro 2016 have ended unsuccessfully.[272]

The TVF Burhan Felek Sport Hall is one of the major volleyball arenas in the city and hosts clubs such as Eczacıbaşı VitrA, Vakıfbank SK, and Fenerbahçe who have won numerous European and World Championship titles.

Between 2005 and 2011, Istanbul Park racing circuit hosted the annual Formula One Turkish Grand Prix.[273] Istanbul Park was also a venue of the World Touring Car Championship and the European Le Mans Series in 2005 and 2006, but the track has not seen either of these competitions since then.[274][275] It also hosted the Turkish Motorcycle Grand Prix between 2005 and 2007. Istanbul was occasionally a venue of the F1 Powerboat World Championship, with the last race on the Bosphorus strait on 12–13 August 2000.[276] The last race of the Powerboat P1 World Championship on the Bosphorus took place on 19–21 June 2009.[277] Istanbul Sailing Club, established in 1952, hosts races and other sailing events on the waterways in and around Istanbul each year.[278][279] Turkish Offshore Racing Club also hosts major yacht races, such as the annual Naval Forces Trophy.[280]

Media

Most state-run radio and television stations are based in Ankara, but Istanbul is the primary hub of Turkish media. The industry has its roots in the former Ottoman capital, where the first Turkish newspaper, Takvim-i Vekayi (Calendar of Affairs), was published in 1831. The Cağaloğlu street on which the newspaper was printed, Bâb-ı Âli Street, rapidly became the center of Turkish print media, alongside Beyoğlu across the Golden Horn.[281]

Istanbul now has a wide variety of periodicals. Most nationwide newspapers are based in Istanbul, with simultaneous Ankara and İzmir editions.[282] Hürriyet, Sabah, Posta and Sözcü, the country's top four papers, are all headquartered in Istanbul, boasting more than 275,000 weekly sales each.[283] Hürriyet's English-language edition, Hürriyet Daily News, has been printed since 1961, but the English-language Daily Sabah, first published by Sabah in 2014, has overtaken it in circulation. Several smaller newspapers, including popular publications like Cumhuriyet, Milliyet and Habertürk are also based in Istanbul.[282] Istanbul also has long-running Armenian language newspapers, notably the dailies Marmara and Jamanak and the bilingual weekly Agos in Armenian and Turkish.

Radio broadcasts in Istanbul date back to 1927, when Turkey's first radio transmission came from atop the Central Post Office in Eminönü. Control of this transmission, and other radio stations established in the following decades, ultimately came under the state-run Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), which held a monopoly on radio and television broadcasts between its founding in 1964 and 1990.[284] Today, TRT runs four national radio stations; these stations have transmitters across the country so each can reach over 90 percent of the country's population, but only Radio 2 is based in Istanbul. Offering a range of content from educational programming to coverage of sporting events, Radio 2 is the most popular radio station in Turkey.[284] Istanbul's airwaves are the busiest in Turkey, primarily featuring either Turkish-language or English-language content. One of the exceptions, offering both, is Açık Radyo (94.9 FM). Among Turkey's first private stations, and the first featuring foreign popular music, was Istanbul's Metro FM (97.2 FM). The state-run Radio 3, although based in Ankara, also features English-language popular music, and English-language news programming is provided on NTV Radyo (102.8 FM).[285]

TRT-Children is the only TRT television station based in Istanbul.[286] Istanbul is home to the headquarters of several Turkish stations and regional headquarters of international media outlets. Istanbul-based Star TV was the first private television network to be established following the end of the TRT monopoly; Star TV and Show TV (also based in Istanbul) remain highly popular throughout the country, airing Turkish and American series.[287] Kanal D and ATV are other stations in Istanbul that offer a mix of news and series; NTV (partnered with U.S. media outlet MSNBC) and Sky Turk—both based in the city—are mainly just known for their news coverage in Turkish. The BBC has a regional office in Istanbul, assisting its Turkish-language news operations, and the American news channel CNN established the Turkish-language CNN Türk there in 1999.[288]

Education

Istanbul University, founded in 1453, is the oldest Turkish educational institution in the city. Although originally an Islamic school, the university established law, medicine, and science departments in the 19th century and was secularized after the founding of the Turkish Republic.[289] Istanbul Technical University, founded in 1773, is the world's third-oldest university dedicated entirely to engineering sciences.[290][291] These public universities are two of just eight across the city;[292] other prominent state universities in Istanbul include the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, which served as Turkey's primary institution of art until the 1970s,[230] and Marmara University, the country's third-largest institution of higher learning.[293]

Most established universities in Istanbul are backed by the government; the city also has several prominent private institutions. The first modern private university in Istanbul, also the oldest American school in existence in its original location outside the United States, was Robert College, founded by Christopher Robert, an American philanthropist, and Cyrus Hamlin, a missionary devoted to education, in 1863. The tertiary element of its education program became the public Boğaziçi University in 1971; the remaining portion in Arnavutköy continues as a boarding high-school under the name Robert College.[294][295] Private universities were officially outlawed in Turkey before the Constitution of 1982, but there were already fifteen private "higher schools", which were effectively universities, in Istanbul by 1970. The first private university established in Istanbul since 1982 was Koç University (founded in 1992), and another dozen had opened within the following decade.[294] Today, there are at least 30 private universities in the city, including Istanbul Commerce University and Kadir Has University.[296] A new biomedical research and development hub, called Bio Istanbul, is under construction in Başakşehir, and will host 15,000 residents, 20,000 working commuters, and a university upon completion.[297][298]

In 2007, there were about 4,350 schools, about half of which were primary schools; on average, each school had 688 students. In recent years, Istanbul's educational system has expanded substantially; from 2000 to 2007, the number of classrooms and teachers nearly doubled and the number of students increased by more than 60 percent.[299] Galatasaray High School, established in 1481 as the Galata Palace Imperial School, is the oldest high school in Istanbul and the second-oldest educational institution in the city. It was built at the behest of Sultan Bayezid II, who sought to bring students with diverse backgrounds together as a means of strengthening his growing empire.[300] It is one of Turkey's Anatolian High Schools, elite public high schools that place a stronger emphasis on instruction in foreign languages. Galatasaray, for example, offers instruction in French; other Anatolian High Schools primarily teach in English or German alongside Turkish.[301][302] The city also has foreign high schools, such as Liceo Italiano, that were established in the 19th century to educate foreigners.[303]

Kuleli Military High School, along the shores of the Bosphorus in Çengelköy, and Turkish Naval High School, on one of the Princes' Islands, were military high schools, complemented by three military academies—the Turkish Air Force, Turkish Military, and Turkish Naval Academies. Both schools were shut Darüşşafaka High School provides free education to children across the country missing at least one parent. Darüşşafaka begins instruction with the fourth grade, providing instruction in English and, starting in sixth grade, a second foreign language—German or French.[304] Other prominent high schools in the city include Istanbul Lisesi (founded in 1884), Kabataş Erkek Lisesi (founded in 1908)[305] and Kadıköy Anadolu Lisesi (founded in 1955).[306]

In 1909, in Constantinople there were 626 primary schools and 12 secondary schools. Of the primary schools 561 were of the lower grade and 65 were of the higher grade; of the latter, 34 were public and 31 were private. There was one secondary college and eleven secondary preparatory schools.[307]

Public services

Istanbul's first water supply systems date back to the city's early history, when aqueducts (such as the Valens Aqueduct) deposited the water in the city's numerous cisterns.[308] At the behest of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Kırkçeşme water supply network was constructed; by 1563, the network provided 4,200 cubic meters (150,000 cu ft) of water to 158 sites each day.[308] In later years, in response to increasing public demand, water from various springs was channeled to public fountains, like the Fountain of Ahmed III, by means of supply lines.[309] Today, Istanbul has a chlorinated and filtered water supply and a sewage treatment system managed by the Istanbul Water and Sewerage Administration (İstanbul Su ve Kanalizasyon İdaresi, İSKİ).[310]