Transport in London

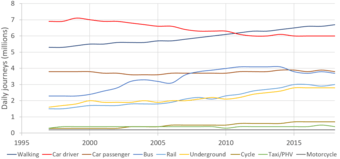

London has an extensive and developed transport network which includes both private and public services. Journeys made by public transport systems account for 37% of London's journeys while private services accounted for 36% of journeys, walking 24% and cycling 2%.[1] London's public transport network serves as the central hub for the United Kingdom in rail, air and road transport.

Clockwise from the top right picture: Docklands Light Railway, Thames Clipper, Heathrow Airport, National Rail train at King's Cross station, AEC Routemaster double decker bus, London Underground train | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | London and surrounding regions |

| Transit type | Rapid transit, commuter rail, light metro, light rail, buses, private automobile, Taxicab, bicycle, pedestrian |

Public transport services are dominated by the executive agency for transport in London: Transport for London (TfL). TfL controls the majority of public transport, including the Underground, Buses, Tramlink, the Docklands Light Railway, London River Services and the London Overground. Other rail services are either franchised to train operating companies by the Department for Transport (DfT) or, like Eurostar and Heathrow Express, operated on an open-access basis. TfL also controls most major roads in London, but not minor roads. In addition, there are several independent airports serving London, including Heathrow, the busiest airport in Europe.[2]

History

| Dates | Organisation | Overseen by |

|---|---|---|

| 1933-1947 | London Passenger Transport Board | London County Council |

| 1948-1962 | London Transport Executive | British Transport Commission |

| 1963-1969 | London Transport Board | Minister of Transport |

| 1970-1984 | London Transport Executive (Greater London only) | Greater London Council |

| 1970-1986 | London Country Bus Services (Green Line only) | National Bus Company |

| 1984-2000 | London Regional Transport | Secretary of State for Transport |

| 2000- | Transport for London | Mayor of London |

Early public transport in London began with horse-drawn omnibus services in 1829, which were gradually replaced by the first motor omnibuses in 1902. Over the years the private companies which began these services amalgamated with the London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) to form a unified bus service. The Underground Electric Railways Company of London, also formed in 1902, unified the pioneering underground railway companies which built the London Underground; in 1912 the Underground Group took over the LGOC and in 1913 it also absorbed the London tramway companies. The Underground Group became part of the new London Passenger Transport Board (LTPB) in 1933; Underground trains, buses and trams began to operate under the shorter London Transport brand name.

The London Transport name continued in use until 2000, although the political management of transport services changed several times. The LPTB oversaw transport from 1933 to 1947 until it was re-organised into the London Transport Executive (1948 to 1962).[4] Responsibility for London Transport was subsequently taken over to the London Transport Board (1963 to 1969), the Greater London Council (1970 to 1984) and London Regional Transport (1984 to 2000). Following the privatisation of London bus services in 1986, bus services were spun off to a separate operation based on competitive tendering, London Buses. In 2000, as part of the formation of the new Greater London Authority, responsibility for London transport was taken over by a new transport authority, Transport for London (TfL), which is the publicly owned transport corporation for the London region today.[5]

Metro and light rail

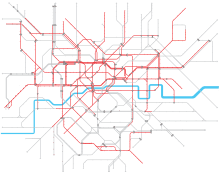

TfL operates three different railway systems across London. The largest is the London Underground, a rapid transit system operating on sub-surface lines and in deep-level "tube" lines. TfL also operates the Docklands Light Railway (DLR), an automated light rail system in the east of the city, and the Tramlink system.[6]

The London Underground and the DLR account for 40 percent of the journeys between Inner London and Outer London, making them the most highly used systems in all of London.[7] These three systems extend to most points of London, creating a comprehensive and extensive system. One major area missed by these systems is South London, which is dominated by a large suburban rail network.

London Underground

Colloquially known as the Tube, the London Underground was the first rapid transit system in the world, having begun operations in 1863.[8] More than 3 million passengers travel on the Underground every day, amounting to over 1 billion passenger journeys per year for the first time in 2006.[9][10] The Underground has 11 lines, most of which connect the suburbs to Central London and together form a dense network in central London, linking major railway stations, central business areas and icons. The Underground serves North London much more extensively than South London. This is the result of a combination of unfavourable geology, historical competition from surface railways and the historical geography of London which was focused to the north of the River Thames. South London is served primarily by surface railways (the majority of London Underground's route length is actually on the surface rather than in tunnel.)

Carrying nearly 50% of London's commuters, the Tube is the most heavily used mode of public transport in the area.[7]

Docklands Light Railway

The Docklands Light Railway (DLR) is an automated light rail system serving the Docklands area of east London. It complements the London Underground, largely sharing its fares system and having a number of interchanges with it.

The DLR serves over 101 million passengers a year and is an essential piece of infrastructure to East London.[11] The DLR's most heavily used stations are Bank, Canary Wharf, Canning Town, Lewisham and Woolwich Arsenal.[12]

Partly thanks to the success of Canary Wharf, the system has expanded several times and now has five main branches connecting the Isle of Dogs and Royal Docks to each other and to the City of London, Stratford, Woolwich and Lewisham south of the river. It also serves London City Airport and Stratford International. A further extension to Dagenham Dock was proposed, but later cancelled by Mayor of London Boris Johnson in 2008.[13] The Dagenham Dock extension has featured in later plans,[14] but its status is uncertain.

Tramlink

The Tramlink is a tram and light rail system serving Croydon and surrounding areas. It operates in the boroughs of Bromley, Croydon and Merton and has 39 stations. In 2011, it carried over 28 million passengers, up from 18 million in 2001.[15]

The system runs on its own right of way, mixed use rails and with street traffic. The network has connections with the London Underground, the London Overground and the National Rail system. There are several extensions planned for the system, such as expanding its coverage and further integrating it into the Underground system.

Heavy rail

London is the focal point of the British railway network, with 18 major stations providing a combination of suburban, intercity, airport and international services; 13 of these stations are termini and 5 are through stations, while two others are both. Most areas of the city not served by the Underground or DLR are served by suburban heavy rail services into one of these stations. These suburban rail services are not part of Transport for London (apart from London Overground and TfL Rail) but are owned and operated by a number of private rail firms and use TfL's Oyster card system.

The terminal (only) stations are Cannon Street, Charing Cross, Euston, Fenchurch Street, King's Cross, Liverpool Street, Marylebone, Moorgate, Paddington, Victoria and Waterloo.

The through (only) stations are Waterloo East, City Thameslink, Farringdon, Old Street, Vauxhall.

The 'mixed' stations are St Pancras, Blackfriars and London Bridge.

London is also linked by rail to mainland Europe by High Speed 1 (HS1) through the Channel Tunnel Rail Link. High-speed Eurostar trains serve Paris and Brussels. Eurostar's London terminus is at St Pancras International and the HS1 route passes through Stratford International and two stations in the county of Kent, Ashford International and Ebbsfleet International.

Local and regional

London is the centre of an extensive radial commuter railway network which, along with Paris, is the busiest and largest in Europe, serving the surrounding metropolitan area. Each terminus is associated with commuter services from a particular segment of this area. The majority of commuters to central London (about 80% of 1.1 million) arrive by either the Underground (400,000 daily) or by surface railway into these termini (860,000 daily).[16]

For historical reasons, London's commuter rail network is arranged in a radial form, and as a result the majority of services entering London terminate at one of the terminal stations around the edge of the city centre.

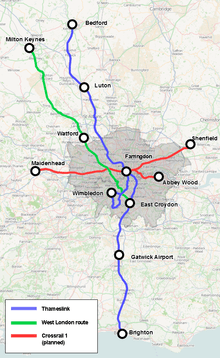

In contrast to the more developed regional RER network in Paris, only two long-distance National Rail lines currently go across London: the Thameslink route runs between the more distant towns of Bedford in the north and Brighton on the south coast, passing through the City of London, London suburbs as well as Luton Airport Parkway and Gatwick Airport, while the West London Route goes via Shepherd's Bush and is operated by Southern running between Milton Keynes Central in the north and East Croydon in the south.[17] A major expansion of the Thameslink route is planned 2013–18, in which a number of existing regional rail services will be redirected via the cross-London Thameslink corridor.[18]

Constantly increasing pressure on the commuter rail systems and on the Underground to disperse passengers from the busy terminals has led to the multibillion-pound Crossrail scheme. When completed, Crossrail will add a further cross-London line passing through Paddington and Liverpool Street. Construction work is currently underway, and twin 16-km tunnels are being bored underneath the city centre. New or upgraded stations will be provided at key city centre locations, linking to the Underground.

While most stations in central London are termini, there are a few notable exceptions. London Bridge station has several through lines to the more central termini at Cannon Street and Charing Cross, and trains to the latter also call at Waterloo East, linked to Waterloo by a footbridge. London Bridge's through platforms are also used by the Thameslink services of Govia Thameslink Railway, which cross the city centre, calling at Blackfriars, City Thameslink, Farringdon and St Pancras.

London Overground

In addition to London's radial lines and cross-London routes, there are also several orbital National Rail lines connecting peripheral inner-London suburbs. These lines have been under the management of TfL since November 2007 and are operated by private contract under the London Overground brand. This commuter transport is operated as a rapid transit system with high-frequency services around a circular route with radial branch lines and is designed to reduce stress from the inner-city Tube network by allowing commuters to travel across London without going through the central Zone 1.[19]

London Overground was formed by joining a series of existing railway lines to form a circular route around the city and incorporates the oldest part of the Underground's history, the Thames Tunnel under the River Thames, which was completed in 1843. The routes comprise:

- The North London Line, which arcs across North London from Richmond in the west via Willesden Junction and Highbury & Islington to Stratford in the east.

- The West London Line linking Clapham Junction to Willesden Junction with some trains to Stratford via the North London Line.

- The East London Line (including the South London Line), a former London Underground line which was converted to heavy rail operation in 2010; part of the Brighton Main Line between New Cross Gate and Norwood Junction; and the South London Line which was added to the London Overground network in December 2012, completing the circuit across the South London suburbs to Clapham Junction.[20] Running from Highbury & Islington to New Cross, West Croydon, and Crystal Palace, and via the South London Line, Clapham Junction.

Other routes operated include:

- The Gospel Oak to Barking Line which links inner North London to the northeastern suburbs, which is due to be extended to Barking Riverside.

- The inner-suburban Watford DC Line from Euston to Watford Junction.

- Suburban services from Liverpool Street to Chingford, Enfield Town and Cheshunt via Hackney Downs.

- The Romford to Upminster Line via Emerson Park.

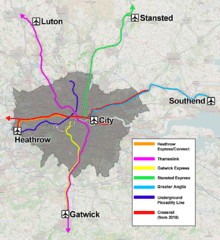

Airport services

Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted airports are served by dedicated train services, and are also served by standard commuter services. The Heathrow Express service from Paddington is provided by the airport operator, Heathrow Airport Holdings, whilst the Gatwick Express from Victoria and Stansted Express from Liverpool Street are provided by franchised train operating companies.

| Airport | Train operator | Central London station | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| City | DLR | Bank/Tower Gateway | |

| Gatwick | Gatwick Express | Victoria | Non-stop service, sub brand of Govia Thameslink Railway |

| Gatwick | Southern | Victoria | Semi-fast and fast service via Clapham Junction |

| Gatwick | Thameslink | St Pancras/Farringdon/City Thameslink/Blackfriars/London Bridge | Thameslink route service |

| Heathrow | Heathrow Express | Paddington | Non-stop service between Central London and the Airport, serves Terminals 2 & 3, then terminates at Terminal 5 |

| Heathrow | London Underground | Several including King's Cross St Pancras | Piccadilly line service |

| Heathrow | TfL Rail | Paddington | An all station suburban service that serves Terminals 2 & 3, then terminates at Terminal 4 |

| Luton | Thameslink | St Pancras/Farringdon/City Thameslink/Blackfriars/London Bridge | Thameslink route service |

| Stansted | Stansted Express | Liverpool Street | Limited stop service, sub brand of Abellio Greater Anglia |

| Southend | Abellio Greater Anglia | Liverpool Street |

Operators

Unlike the Underground, which is a single system owned and operated by Transport for London, commuter railways in London are run by a number of separate train operating companies (TOCs). This results from the privatisation of British Rail in the 1990s which split the former state railway operator British Rail into a number of smaller franchises in order to increase competition and allow railways to operate in a free market.

Among the rail firms operating passenger services in London, a number are owned by foreign companies or by state-owned railways of other European countries.[21][22][23] London Overground is contracted in a different way to other franchises in that it is operated by a private company under contract to Transport for London. Heathrow Express is also unusual in that it is not officially part of the National Rail franchising system.

| Train operator | Franchise/services | Parent company/owner |

|---|---|---|

| Arriva Rail London | London Overground metro service across London | Arriva |

| c2c | Essex Thameside – local and regional/commuter services from Fenchurch Street to East London and South Essex | Trenitalia |

| Chiltern Railways | London to Aylesbury Line – local and regional/commuter services from Marylebone to North West London, Buckinghamshire | Arriva |

| East Midlands Railway | Regional services from St Pancras to Corby | Abellio |

| Govia Thameslink Railway | Thameslink Southern & Great Northern franchise – operate under the Gatwick Express, Great Northern, Southern, and Thameslink brands from King's Cross, Moorgate, Blackfriars, London Bridge and Victoria to North London, South London, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire, Kent and Sussex, also operate cross city services via the Thameslink route | Govia |

| Great Western Railway | Greater Western franchise – local and regional/commuter services from Paddington to West London and the Thames Valley | FirstGroup |

| Greater Anglia | East Anglia franchise – local and regional/commuter services from Liverpool Street to Essex, Hertfordshire and Cambridgeshire, also operate the Stansted Express | Abellio / Mitsui |

| Heathrow Express | Non-stop service from Paddington to Heathrow Airport | Heathrow Airport Holdings |

| London Northwestern Railway | Local and regional/commuter services from Euston to Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Northamptonshire, Warwickshire, Staffordshire and Birmingham | Abellio / JR East / Mitsui |

| South Western Railway | South Western franchise – local services from Waterloo to South West London and regional/commuter services to Surrey, Hampshire, Dorset & Berkshire | FirstGroup / MTR Corporation |

| Southeastern | South Eastern franchise – local metro services across South East London and commuter and regional services from Victoria, Charing Cross, Cannon Street, Blackfriars and St Pancras to Kent | Govia |

| TfL Rail | Local and commuter services from Liverpool Street to Gidea Park and Shenfield, plus Paddington to Hayes & Harlington and Heathrow Terminal 4, will operate the Elizabeth line from 2019 | MTR Corporation |

National InterCity

Long-distance intercity services are provided at some London rail termini. Because the termini and intercity routes were largely built by competing companies, many termini serve cities in overlapping regions or different parts of the same region:

- Euston for the West Midlands, North Wales, North West England and Scotland

- St Pancras for the East Midlands and parts of Yorkshire

- King's Cross for the East Midlands, Yorkshire, North East England and Scotland

- Liverpool Street for East Anglia

- Paddington for South West England and South Wales

International

St Pancras provides international Eurostar services via the Channel Tunnel to cities including Paris, Brussels, Lyon and Marseilles, with journeys to Paris in around 2 hours 15 minutes and to Brussels in around 1 hour 50 minutes. Journeys have also started to Amsterdam.[24]

It is also possible to purchase combined train and ferry tickets on the Dutchflyer service to the Netherlands[25] as well as the Irish Ferries service to the Republic of Ireland.[26]

Ticketing

London commuters mostly gain access to public transport services in London by using one of the inter-modal travel tickets provided by Transport for London. Oyster card is a credit-card-sized electronic ticket which offers almost unlimited use on the London Underground, London Overground, Docklands Light Railway, Tramlink, London Buses and National Rail services in the Greater London area.[27] Commuters entering London from further afield may rely on the older paper Travelcard (combined with a National Rail ticket) which offers the same inter-modal access but is valid at the regional railway stations not yet equipped to offer electronic ticketing. Oyster card is generally not valid outside the London fare zones or on certain airport express services.

Both Travelcard and Oyster card fares are calculated by using a system of fare zones which divides London's transport network into concentric circles numbered 1–6. Individual transport operators may also offer their own ticketing and fare tariffs for travel on one mode of transport.

The London Pass offers tourists visiting London a combination of the Travelcard and admissions to a number of tourist attractions for a set fee in advance.

Roads

.png)

London has a hierarchy of roads ranging from major radial and orbital trunk roads down to minor "side streets". At the top level are motorways and grade-separated dual carriageways, supplemented by non-grade-separated urban dual carriageways, major single carriageway roads, local distributor roads and small local streets.

Most of the streets of central London were laid out before cars were invented, and London's road network is often congested. Attempts to tackle this go back at least to the 1740s, when the New Road was built through the fields north of the city; it is now just another congested central London thoroughfare. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, new wide roads such as Victoria Embankment, Shaftesbury Avenue and Kingsway were created. In the 1920s and 1930s a series of new radial roads, such as the Western Avenue and Eastern Avenue, were constructed in the new suburban outskirts of London, but little was done in the congested central area.

A 1938 report, The Highway Development Survey, by Sir Charles Bressey and Sir Edwin Lutyens for the Ministry of Transport and Sir Patrick Abercrombie's 1943 County of London Plan and 1944 Greater London Plan all recommended the construction of many miles of new roads and the improvement of existing routes and junctions; but little was done to implement the recommendations. In the 1960s the Greater London Council prepared a drastic plan for a network of London Ringways including the construction of the London Motorway Box which would have involved massive demolition and huge cost to bring motorways into the heart of the city. Resistance from central government over the costs, and campaigns of objections from local residents, caused the cancellation of most of the plans in 1973. By the end of the 20th century policy swung towards a preference for public transport improvements, although the 118-mile (190 km) M25 orbital motorway was constructed between 1973 and 1986 to provide a route for traffic to bypass the London urban area.

Major routes

Due to the opposition to the Ringway plan and earlier proposals there are few grade-separated routes penetrating to the city centre. Only the western A40, northeastern A12 Leyton By-pass, eastern A13 and southeastern A2 are grade-separated for most of the way into central London. There is also the eastern A1203, a dual carriageway tunnel around the Docklands area, which directly links onto the A13.

There is a technical distinction between the motorways, operated by the Highways Agency, and other major routes, operated by TfL as the Transport for London Route Network (TLRN). Many of London's major radial routes continue far beyond the city as part of the national motorway and trunk road network.

From the north, clockwise (and noting a key commuter location served by each rather than the final destination), the major radial routes are the A10 (north to Hertford), the M11 (north to Cambridge), the A12 (northeast to Chelmsford), the A127 (east to Southend), the A13 (also east to Southend), the A2/M2 (east to Chatham), the A20/M20 (east to Maidstone), the A23/M23 (south to Gatwick Airport and Brighton), the A3 (southwest to Guildford), A316/M3 (southwest to Basingstoke), the A4/M4 (west to Heathrow Airport and Reading), the A40/M40 (west to Oxford), the M1 (northwest to Luton & Milton Keynes) and the A1 (north to Stevenage).

There are also three ring roads linking these routes orbitally. The innermost, the Inner Ring Road, circumnavigates the congestion charging zone in the city centre. The generally grade-separated North Circular Road (the A406 from Gunnersbury to East Ham) and the non-separated South Circular Road (the A205) form a suburban ring of roughly 10 km radius. Finally, the M25 encircles most of the urban area with roughly a 25 km radius. The western section of the M25 past Heathrow Airport is one of Europe's busiest, carrying around 200,000 vehicles per day.

None of these roads have tolls, although the Dartford Crossing, which links the two ends of the M25 to the east of London, is tolled.

Distributor and minor routes

The major roads mentioned above are supplemented by a host of standard single-carriageway main roads, operated as part of the afore-mentioned TLRN. These roads generally link suburbs with each other, or deliver traffic from the ends of the major routes into the city centre.

The TLRN is supplemented by local distributor roads operated by the local authorities, the London boroughs. These non-strategic roads only carry local traffic.

Congestion charge and emissions charges

In 2003, TfL introduced a scheme to charge motorists £5 per day for driving vehicles within a designated area of central London during peak hours, the congestion charge.[29] The politicians behind the scheme claim that it has significantly reduced traffic congestion and hence improved reliability of bus and taxi services,[30] but this is strongly contested by the scheme's critics. The charge was increased to £8 per day in 2005.[31] From 2007 to December 2010, the zone was extended to cover most of Kensington and Chelsea.[32][33] As of 2019, around 90,000 vehicles drive into the congestion charging zone each day, down from over 100,000 in 2017.[34]

The T-charge (toxicity charge) was introduced from October 2017 for vehicles that do not meet Euro 4 standards. These older polluting vehicles paid an extra £10 charge on top of the congestion charge to drive within the Congestion Charge Zone.[35][36] In April 2019, the T-charge was replaced by the Ultra-Low Emission Zone, which applies to vehicles which do not meet Euro 4 standards for petrol and Euro 6 for diesel and operate 24/7.

The zone will be extended to the North and South Circular from 2021 so that it would cover an area containing 3.8 million people.[37][38] Once the zone is expanded, an estimated 100,000 cars, 35,000 vans and 3,000 lorries will pay the charge daily.[39]

Road casualties in London

The following table shows the number of casualties, grouped by severity, on the roads of Greater London (including the City of London), over recent years.[40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49] However, data from the years 2017 and onwards should not be directly compared with previously collected data due to the introduction of online self reporting.[49]

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal | 204 | 184 | 126 | 159 | 134 | 132 | 127 | 136 | 116 | 131 | 112 |

| Serious | 3,322 | 3,043 | 2,760 | 2,646 | 2,884 | 2,192 | 2,040 | 1,956 | 2,385 | 3,750 | 3,953 |

| Total | 3,526 | 3,227 | 2,886 | 2,805 | 3,018 | 2,324 | 2,167 | 2,092 | 2,501 | 3,881 | 4,065 |

| Slight | 24,627 | 24,752 | 26,003 | 26,452 | 25,762 | 24,875 | 28,618 | 28,090 | 27,769 | 28,686 | 26,526 |

| Grand total | 28,361 | 27,979 | 28,889 | 29,257 | 28,780 | 27,199 | 30,785 | 30,182 | 30,270 | 32,567 | 30,591 |

From 2020, TfL will introduce the Direct Vision Standard which will require HGVs over 12 tonnes to be able to see someone to the side or the front of their cab.

Cycling

Over one million Londoners own bicycles but as of 2008 only around 2 per cent of all journeys in London are made by bike: this compares poorly to other major European cities such as Berlin (5 per cent), Munich (12 per cent), and Amsterdam (55 per cent)[50] and Copenhagen (36 per cent).[51] Nevertheless, this is an 83 per cent increase compared to that in 2000.[52] There are currently an estimated 480,000 cycle journeys each day in the capital.

The Santander Cycles (formerly Barclays Cycle Hire) scheme, launched 30 July 2010, aims to provide 6,000 bicycles for rental.[53] Bikes are available at a number of docking stations in central London.

Buses

The red double-decker London bus has entered popular culture as an internationally recognised icon[54] of England. While the design and operation of London buses has changed over the years, the vehicles still maintain their traditional red colour.[55]

The London bus network is extensive, with over 6,800 scheduled services every weekday carrying about six million passengers on over 700 different routes making it one of the most extensive bus systems in the world and by far the largest in Europe.[56] Catering mainly for local journeys, it carries more passengers than the Underground. In addition to this extensive daytime system, a 100-route night bus service is also operated, providing a 24-hour service.

The London Buses network and its branded services, the Red Arrow and East London Transit systems are managed by TfL through its arms-length subsidiary company, London Buses Ltd. As a result of the Privatisation of London bus services in the mid-1990s, bus operations in London are put out to competitive tendering and routes are operated by a number of private companies, while TfL sets the routes, frequencies, fares and even the type of vehicle used (Greater London was exempted from the bus deregulation in Great Britain). Transport companies may bid to run London bus services for a fixed price for several years, with incentives and penalties in place to encourage good performance against certain criteria.[57] The tendering system is open to transport operators from a global market, with the result that some London bus services are now operated by international groups such as RATP Group, the state-owned operator of the Paris public transport system.[22][23][58]

| Operator | Routes | TfL routes | Parent company |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abellio London | London | Yes | Abellio |

| Arriva London | London | Yes | Arriva |

| Carousel Buses | Buckinghamshire | No | Go-Ahead Group |

| CT Plus | Greater London | Yes | HCT Group |

| First Berkshire & The Thames Valley | Berkshire | No | FirstGroup |

| Go-Ahead London | London | Yes | Go-Ahead Group |

| Green Line Coaches | Express services to Berkshire & Hertfordshire | No | Arriva |

| London Sovereign | North London | Yes | RATP Group |

| London United | West & Central London | Yes | RATP Group |

| Metrobus | South and South-east London, and parts of Surrey, Kent, West and East Sussex | No | Go-Ahead Group |

| Metroline | North & West London | Yes | ComfortDelGro |

| Quality Line | South London & Surrey | Yes | RATP Group |

| Stagecoach London | South and East London | Yes | Stagecoach Group |

| Sullivan Buses | Hertfordshire & North London | Yes | - |

| Tower Transit | East, West & Central London | Yes | Transit Systems |

| Uno | Hertfordshire & North London | Yes | University of Hertfordshire |

Many services are operated with the iconic red double-decker buses, virtually all using modern low-floor accessible vehicles rather than the traditional open-platform AEC Routemasters, now limited to two city centre "heritage routes" after a phase out in 2006. However a new Routemaster has come into service following the withdrawal of the articulated buses called New Routemaster which is a modern version of the Routemaster which started service in 2012.

The bus system has been the subject of much investment since TfL's inception in 2000, with consequent improvements in the number of routes (particularly night services), their frequency, reliability and the standard of the vehicles used.

Taxis

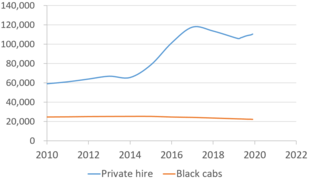

Black cabs and hire cars

The iconic black cab remains a common sight. They are driven by the only taxicab drivers in the world who have spent at least three years learning the city's road network to gain "The Knowledge". All London taxicabs are licensed by TfL's Public Carriage Office (PCO), who also set taxicab fares along with strict maximum vehicle emission standards. Black cabs can be hailed on the street or hired from a taxicab rank (found at all the mainline railway termini and around the major business, shopping and tourist centres). Taxicab fares are set by TfL and are calculated using a taximeter in the vehicle (hence the name "taxicab") and are calculated using a combination of distance travelled and time.

Private hire vehicles (PHVs or minicabs) are cars which are not licensed to pick people up on the street. They must always be booked in advance by phone or the internet or at the operator's offices.

Horse-drawn vehicles

More than 70 years after horse-drawn carriages were restricted from the West End, Westminster City Council has announced that it will consider supporting applications to reintroduce them for sightseeing tours across the city.[60] The first Hackney carriages licensed in London, in 1662, were horse-drawn vehicles.

Bicycle taxis and pedicabs

Pedicabs are a fairly recent addition, being mostly used by tourists and operating in the central areas. Cambridge Trishaws Ltd moved from Cambridge to London in 1998 as the first such company to work within the city. There are now 5–10 such companies providing competing services. The Licensed Taxi Drivers Association (LTDA) went to the High Court to try to force them to become licensed, but lost their case in 2004.[61]

There has been a move, led by Chris Smallwood, chairman of the London Pedicab Operators Association, to bring in more relevant legislation. Smallwood helped to draft an amendment to a bill to be put before the House of Lords that would introduce these 'lighter' pedicab regulations. This was followed in 2005 by Transport Committee scrutiny to determine the future of the then nascent industry. This led in turn, to a 2006 TfL consultation "for the introduction of a licensing regime that is appropriate for pedicabs and their riders".[62]

Airports

The London airport system is the busiest in the world, with more than 170 million passengers using its six airports in 2017.[63] In order of size, these airports are Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted, Luton, London City, and Southend.

Heathrow and Gatwick serve long-haul, European and domestic flights; Southend is used mostly for European flights; Stansted and Luton handle low-cost European and domestic services; whilst London City caters for business passengers to short-haul and domestic destinations. A small number of long-haul flights depart from Stansted and London City.

The closest airport to the city centre is London City in the Docklands area, about 10 km east of the City of London financial district. A branch of the Docklands Light Railway links the airport to the City in under 25 minutes.[64]

Two other airports are at the edge of the city but within the Greater London boundary: Biggin Hill, around 23 km southeast of the centre, and London's principal airport, Heathrow, 20–25 km from central London.

Heathrow handles nearly 70 million passengers per annum, making it Europe's busiest airport. On the western edge of the city in the London Borough of Hillingdon, it has two runways and five passenger terminals, with the £4bn fifth terminal opening in 2008. It is connected to central London by the dedicated Heathrow Express rail service, the Elizabeth line local rail service and London Underground's Piccadilly line, and is connected to the M4 and M25 motorways.

Gatwick is just under 40 km south of central London in Sussex, some distance outside London's boundary. With a single runway and two terminals, it handles about 32 million passengers per year from domestic, short-haul and long-haul flights, and is linked to London by the Gatwick Express, Thameslink and Southern rail services, and by the M23. It is the busiest single runway airport in the world.

Southend is to the east of London, and was developed rapidly to be usable by short-haul passenger flights in time for the 2012 Summer Olympics. It is connected to London via the A127 road, and an on-airport station with services through Stratford to London Liverpool Street. Passenger numbers have risen significantly from April 2012 when low-cost flights commenced to 13 European destinations.

Stansted is London's most distant airport, about 50 km north of the centre, in Essex. With a single runway and terminal, it handles about 20 million passengers annually, mostly from low-cost short-haul and domestic leisure flights. It is connected to London by the Stansted Express rail service and the M11 motorway.

Luton Airport is about 45 km northwest of London, connected to it by the M1 and Thameslink trains from nearby Luton Airport Parkway station. It has a single terminal and a runway considerably shorter than the other London airports, and like Stansted it caters mainly for low-cost short-haul leisure flights.

RAF Northolt in west London is used by private jets, and London Heliport in Battersea is used by private helicopters. There are also Biggin Hill and Farnborough Airfield. Croydon Airport was originally London's main airport, but was replaced by Heathrow, and closed in 1959.

An airfield at Lydd has been rebranded London Ashford, but currently has little traffic. In August 2009, Oxford Airport, some 95 km from London's city centre, controversially rebranded itself as London Oxford Airport,[65] while Kent International was briefly called London Manston; it is 120 km from London.

In addition, RAF Brize Norton with direct flights to the Falkland Islands is less than two hours away by car.[66] Though not generally considered London airports, Birmingham Airport and Southampton Airport have been suggested as alternative airports for London due to the existence of direct rail links serving Central London.[67]

Airport transit

Three of London's airports provide varieties of automated people mover (APM) along guided tracks to shuttle passengers between terminals. These small-scale transport systems operate independently of London's main transportation network.

The Gatwick Airport inter-terminal transit, originally built in 1983 and refurbished in 2010, was the first airport driverless train system outside the USA;[68][69] a similar system, the Stansted Airport Transit System, was opened in 1991 at Stansted Airport to provide airside terminal transfers.[70]

At Heathrow Airport, an automated people mover system called the Transit operates airside at Heathrow Terminal 5,[71] and since 2011, a personal rapid transit system called Heathrow Pod has operated between Terminal 5 and the car parks.[72]

Water transport

River Thames

The River Thames is navigable to ocean-going vessels as far as London Bridge, and to substantial craft well upstream of Greater London. Historically, the river was one of London's main transport arteries. Although this is no longer the case, passenger services have seen something of a revival since the creation in 1999 of London River Services, an arm of Transport for London. LRS now regulates and promotes a small-scale network of river bus commuter services and a large number of leisure cruises operating on the river. Boats are owned and operated by a number of private companies, and LRS manages five of central London's 22 piers.[73]

Canals

London also has several canals, including the Regent's Canal, which links the Thames to the Grand Union Canal and thus to the waterway network across much of England. These canals were originally built in the Industrial Revolution for the transport of coal, raw materials and foods. Although they now carry few goods, they are popular with private narrowboat users and leisure cruisers, and a regular "water bus" service operates along the Regent's Canal during the summer months.

Cargo

Some bulk cargoes are carried on the Thames, and the Mayor of London wishes to increase this use. London's port used to be the country's busiest when it was located in Central London and east London's Docklands. Since the 1960s, containerisation has led to almost all of the port's activities moving further downstream and the ceasing of port-related activity at the extensive network of docks (which were built in the 19th and early 20th centuries). A purpose-built container port at Tilbury in Essex, around ten kilometres outside the Greater London boundary, is today the busiest part of the port, though activity remains along stretches of the Thames, mainly downstream of the Thames Barrier. Fifty riverside wharfs have been safeguarded from development in Greater London. Today the port is the UK's second largest by cargo handled (53 million tonnes in 2008).[74] The Port of London Authority is responsible for most port activities and navigation along the River Thames in London and on the Thames estuary.

Aerial lift

The Air Line aerial cable system over the River Thames opened in 2012.

Public transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transport in London, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 84 minutes, and 30% of passengers ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average length of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 13 minutes, while 18% of passengers wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average length of a public transport journey is 8.9 km, while 20% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[75]

See also

References

- "Travel in London Report 9" (PDF). TfL. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- Butler, Alex (23 February 2017). "With passenger numbers hitting record-breaking levels, discover the busiest airports in Europe". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Travel in London Report 12" (PDF). p. 33.

- by S. P. Sinha; Faguni Ram; Manager Prasad; et al., eds. (1993). Instant encyclopaedia of geography. 23. Transportation geography (1st ed.). New Delhi: Mittal publ. p. 295. ISBN 817099506X.

- Martin, Andrew (26 April 2012). Underground, Overground a Passenger's History of the Tube. London: Profile. ISBN 9781847658074.

- "Company information". Transport for London website. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Travel in London" (PDF). TfL. Transport for London. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- "London Underground History". Transport for London website. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "London Underground Key Facts". TfL website. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "Tube carries one billion passengers for first time". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 2 July 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Light Rail and Tram Statistics: England 2013/14" (PDF). Government of the UK. Department for Transport. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- "Freedom of Information DLR usage 1213". Transport for London. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- "TfL scraps projects and cuts jobs". BBC News. 6 November 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "Mayor's Transport Strategy, Chapter five—transport proposals". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- "TRAMLINK OPERATIONS" (PDF). www.tfl.gov.uk. Transport for London. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- The Mayor's Transport Strategy Archived 15 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine – Figure 2.20 and Paragraph 2.76.

- "South London Route Utilisation Strategy" (PDF). Network Rail. March 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "Consultation on the combined Thameslink, Southern and Great Northern franchise" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "About London Overground". Transport for London. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- "Outer London rail orbital opens for passengers". BBC News. 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- Haywood, Russell (2009). Railways, urban development and town planning in Britain : 1948-2008 ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Farnham, England: Ashgate. p. 266. ISBN 9780754673927. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- Brummer, Alex (2012). "7. the Export of Transport". Britain for Sale: British Companies in Foreign Hands. Random House. ISBN 978-1448136810.

- Macalister, Terry; Milmo,Dan (22 April 2010). "Arriva takeover bid revives foreign takeover row". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "England | London | Eurostar arrives in Paris on time". BBC News. 14 November 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- https://www.stenaline.co.uk/ferry-to-holland/rail-and-sail

- https://www.irishferries.com/uk-en/special-offers-from-britain-to-ireland/rail-sail/

- "Tickets". Transport for London website. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- http://democracy.cityoflondon.gov.uk/documents/s91800/Appendix+1+-+Traffic+in+the+City+2018.pdf

- "Smooth start for congestion charge". BBC News. 18 February 2003. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- "Impacts monitoring – Fourth Annual Report Overview" (PDF). Transport for London. June 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- "Congestion charge increases to £8". BBC News. 1 April 2005. Retrieved 8 April 2006.

- Woodman, Peter (19 February 2007). "Capital's congestion charge area extended". The Independent. London. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- Removal of western extension. tfl.gov.uk. 29 July 2018. URL:https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2010/october/mayor-confirms-removal-of-congestion-charge-western-extension-zone-by-christmas-and-introduction-of-cc-auto-pay-in-new-year. Accessed: 2018-07-29. (Archived by WebCite® at https://www.webcitation.org/71HZwFV0r)

- "Two in three vehicles in ULEZ already comply with new pollution rules, data reveals".

- Mason, Rowena (17 February 2017). "London to introduce £10 vehicle pollution charge, says Sadiq Khan". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- Saarinen, Martin (17 February 2017). "London introduces new £10 'T-charge' to cut vehicle pollution". Auto Express. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "London Mayor confirms Ultra-Low Emission Zone will start in 2019". www.fleetnews.co.uk.

- "ULEZ: The politics of London's air pollution".

- "Ultra-low emission zone comes into force in central London".

- Transport for London (2009). Casualties in Greater London during 2008.

- Transport for London (2011). Casualties in Greater London during 2009 and 2010.

- Transport for London (June 2012). Casualties in Greater London during 2011.

- Transport for London (June 2013). Casualties in Greater London during 2012.

- Transport for London (June 2014). Casualties in Greater London during 2013.

- Transport for London (June 2015). Casualties in Greater London during 2014.

- Transport for London (June 2016). Casualties in Greater London during 2015.

- Transport for London (September 2017). Casualties in Greater London during 2016.

- Transport for London (September 2018). Casualties in Greater London during 2017.

- Transport for London (July 2019). Casualties in Greater London during 2018.

- "Amsterdam Edging Ahead of Copenhagen as Most Bike-Loving Euro-Capital?".

- "Bike City Copenhagen". Københavns Kommune. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- "Greater London Authority – Press Release". London.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Quigley-Jones, Jennifer (13 November 2009). "On yer bikes". The Economist. The World in 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- "Our Collection". icons.org.uk. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Elborough, Travis (2006). The bus we loved : London's affair with the Routemaster. London: Granta Books. p. 108. ISBN 9781862078857.

- London Buses, Transport for London. Accessed 10 May 2007.

- Parker, David (2009). The official history of privatisation. London: Routledge. p. 232. ISBN 9780203881521.

- "The French connection: What's a picture of the River Seine doing on our iconic London buses?". Daily Mail. 25 April 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- "Licensing information".

- "Horse-drawn carriages could make West End comeback" (Press release). City of Westminster Council. 22 January 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- "Taxi driver: London". BBC News. 4 August 2004. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- "Public Carriage Office begins consultation on licensing pedicabs in London" (Press release). Transport for London. 29 June 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- "Revealed: The most crowded skies on the planet". The Telegraph. 27 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- London City Airport train timetable, www.tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2005.

- "London Oxford Airport - a Tale of Two Cities". The Telegraph. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- "Google Maps". Google Maps.

- Elledge, John (1 July 2019). "How many airports does London have? | CityMetric". CityMetric. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Hudson, Kenneth (1984). "Airports and Airfields". Industrial history from the air. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-521-25333-8.

- "Press release 2010 – London Gatwick – we have lift on!" (Press release). Gatwick Airport. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "24. BAA Stansted Airport Transit" (PDF). Physics At Work 2008. BAA Stansted/Cambridge University Cavendish Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "INNOVIA APM Automated People Mover System - London Heathrow, UK - United Kingdom - Bombardier". Bombardier. 31 March 2014. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Heathrow: Driverless ULTra Pods Replace Buses At Terminal 5". Huffington Post. 12 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Transport for London. "London River Services". Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- "Port of London Annual Review 2008" (PDF). Port of London Authority. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- "London Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website of Transport for London, the executive agency in charge of most transport operations

- Department for Transport, central government department overseeing the national railway network

- London Campaign for Better Transport, campaigns on local issues, and supports the national organisation in pressing for sustainable transport. A current project is a possible "Brent Cross Railway" in north London.

.jpg)